Therapeutic Effects of the Most Common Polyphenols Found in Sorbus domestica L. Fruits on Bone Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

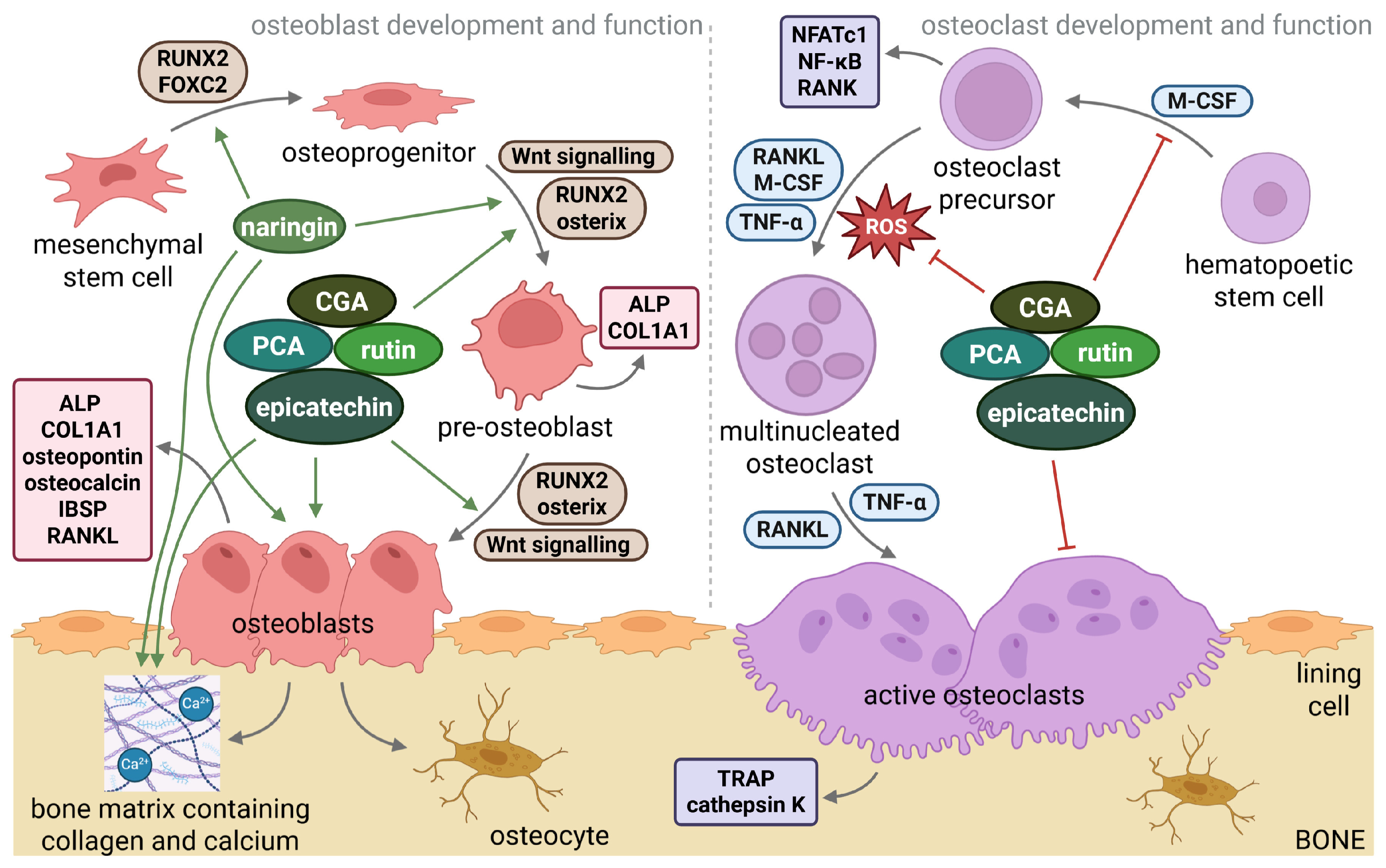

2. Sorbus domestica L. Fruits: Nutrient Composition

3. The Most Common Polyphenols from Sorbus domestica L. Fruits: Their Effects on Bone Health

3.1. Chlorogenic Acid (CGA; 5-CQA)

3.2. Protocatechuic Acid (PCA)

3.3. Rutin (Quercetin-3-O-Rutinoside)

3.4. Epicatechin

3.5. Naringin

4. Physicochemical Properties of Polyphenols and Interactions with Bone-Related and Signalling Mediators

5. Polyphenol-Polyphenol Interactions

| Combination | Concentration | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGA PCA | 0.1 mM 0.1 mM | SYNERGISTIC -enhanced radical scavenging capacity | [162] |

| CGA Rutin | 600 μM 150 μM | ADDITIVE -antioxidant activity | [163] |

| CGA Rutin | 100 μg/mL 100 μg/mL | SYNERGISTIC -inhibition of thyroid peroxidase activity | [164] |

| CGA Rutin | Not specified | ADDITIVE -enhanced antioxidant activity | [165] |

| Epicatechin Rutin | Not specified | ADDITIVE -enhanced antioxidant activity | [165] |

| Naringin Rutin Quercetin | 170 μM 8 μM 8 μM | SYNERGISTIC -anticancer effects, enhanced ROS, apoptosis of HeLa cervical cancer cells | [168] |

| Epicatechin Naringin | 20 µM 25 µM | SYNERGISTIC -increased cell death, anoikis in HCT-116 and T84 cancer cell lines | [169] |

| CGA Quercetin | 600 μM 150 μM | SYNERGISTIC -antioxidant activity | [163] |

6. Polyphenols and Epigenetic Modifications of Bone-Related Targets

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3-HPAA | 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl) acetic acid |

| AKT1 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| Al | aluminum |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ALPL | alkaline phosphatase gene |

| AP-1 | activator protein 1 |

| B | boron |

| BAX | BCL2 associated X |

| Bche | butyrylcholinesterase |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bglap | bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein gene |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BMMs | bone mouse marrow-derived macrophages |

| BMP6 | bone morphogenetic protein 6 gene |

| BMSC | bone mesenchymal stem cells |

| BV/TV | bone volume fraction |

| Ca | calcium |

| CAT | catalase |

| CGA | chlorogenic acid |

| COL1A1 | collagen type I alpha 1 |

| COL1A1 | gene encoding collagen type I alpha 1 |

| COL3A1 | collagen type III alpha 1 gene |

| Conn.D | connectivity density |

| CPT1β | carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 beta gene |

| c-Src | proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Src gene |

| CTx | C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen |

| Cu | copper |

| DEX | dexamethasone |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| dw | dry weight |

| ECAP | epicatechin 3-O-β-D-allopyranoside |

| ESR1 | estrogen receptor 1 |

| FBG | fasting blood glucose |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| Fe | iron |

| FRAP | Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| fw | fresh weight |

| GLUT4 | glucose transporter type 4 gene |

| GPER | G protein-coupled estrogen receptor |

| GPER1 | G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 |

| GPx | glutathione peroxidases |

| GSH | glutathione |

| HbA1c | glycosylated haemoglobin |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| HO-1 | hemoxygenase 1 |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| HPPA | 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl) propionic acid |

| IBSP | integrin-binding sialoprotein gene |

| IBSP | integrin-binding sialoprotein |

| IFN-γ | interferon-gamma |

| IGF-1 | insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| INS | insulin |

| K | potassium |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| M-CSF | macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| Mmp9 | matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene |

| MMP9 | matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinase genes |

| MPO | myeloperoxidase |

| MSC | mesenchymal stem cells |

| MSC-hBM | human mesenchymal stem cells |

| Nfatc1 | nuclear factor of activated T-cells gene |

| NFATC1 | nuclear factor of activated T-cells |

| NF-Κb | nuclear factor kappa B |

| Nrf2 | erythroid 2-related factor transcription factor |

| OPG | osteoprotegerin |

| OVX | ovariectomized |

| P | phosphorus |

| P1NP | procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide |

| p-CA | p-coumaric acid |

| PCA | protocatechuic acid |

| PDLSCs | human periodontal ligament stem cells |

| PPARα | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PTH | parathyroid hormone |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand |

| ROS | oxygen species |

| Runx2 | runt-related transcription factor 2 gene |

| RUNX2 | runt-related transcription factor 2 |

| SMI | structure model index |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| Sp7 | Sp7 transcription factor 7 gene (osterix) |

| SPARC | secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich gene |

| SPP1 | osteopontin gene |

| SPP1 | osteopontin |

| STAT3 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| T2DM | diabetes mellitus type 2 |

| TAG | triacylglycerol |

| Tb.N | trabecular number |

| Tb.Sp | trabecular separation |

| Tb.Th | trabecular thickness |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Traf6 | TNF receptor-associated factor-6 gene |

| TRAP | tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase |

| Trap | tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase gene |

| TSH | thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| UCP1 | uncoupling protein 1 gene |

| XO | xanthine oxidase |

| Zn | zinc |

References

- Enescu, C.; de Rigo, D.; Durrant, T.; Caudullo, G. Sorbus domestica in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; p. e019db5. [Google Scholar]

- Tas, A.; Gundogdu, M.; Ercisli, S.; Orman, E.; Celik, K.; Marc, R.A.; Buckova, M.; Adamkova, A.; Mlcek, J. Fruit Quality Characteristics of Service Tree (Sorbus domestica L.) Genotypes. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 19862–19873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta, M.F.; Kırkaya, H.; Balta, F.; Uzun, S.; Karakaya, O. Evaluation of the Diversity among the Service Tree (Cormus domestica L. Spach) Accessions Grown in the Seben (Bolu, Türkiye) Region Based on Fruit Traits and Bioactive Compounds. Euphytica 2025, 221, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkol, E.; Gürağaç Dereli, F.T.; Taştan, H.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Khan, H. Effect of Sorbus domestica and Its Active Constituents in an Experimental Model of Colitis Rats Induced by Acetic Acid. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 251, 112521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasbal, G.; Yilmaz-Ozden, T.; Sen, M.; Yanardag, R.; Can, A. In Vitro Investigation of Sorbus domestica as an Enzyme Inhibitor. Istanb. J. Pharm. 2020, 50, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termentzi, A.; Alexiou, P.; Demopoulos, V.J.; Kokkalou, E. The Aldose Reductase Inhibitory Capacity of Sorbus domestica Fruit Extracts Depends on Their Phenolic Content and May Be Useful for the Control of Diabetic Complications. Die Pharm.-Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 63, 693–696. [Google Scholar]

- Martiniakova, M.; Biro, R.; Penzes, N.; Sarocka, A.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Omelka, R. Links among Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Osteoporosis: Bone as a Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, R.; Omelka, R.; Sarocka, A.; Penzes, N.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Martiniakova, M. Beneficial Effects of Elaeagnus rhamnoides (L.) A. Nelson and Its Most Abundant Flavonoids on the Main Mechanisms Related to Diabetic Bone Disease. Pharm. Biol. 2025, 63, 460–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Yang, G. Interaction between Diabetes and Osteoporosis: Imbalance between Inflammation and Bone Remodeling. Osteoporos. Int. 2025, 36, 2401–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, H.; Qi, S.; Yang, H.; Hong, X. The Association between Physical Activities Combined with Dietary Habits and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Mondockova, V.; Kovacova, V.; Babikova, M.; Zemanova, N.; Biro, R.; Penzes, N.; Omelka, R. Interrelationships among Metabolic Syndrome, Bone-Derived Cytokines, and the Most Common Metabolic Syndrome-Related Diseases Negatively Affecting Bone Quality. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, R.K.; Gaur, K. Understanding the Impact of Diabetes on Bone Health: A Clinical Review. Metab. Open 2024, 24, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiniakova, M.; Soltesova Prnova, M.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Svik, K.; Londzin, P.; Folwarczna, J.; Omelka, R. Insufficient Impact of the Aldose Reductase Inhibitor Cemtirestat on the Skeletal System in Type 2 Diabetic Rat Model. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0336508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Svik, K.; Londzin, P.; Folwarczna, J.; Soltesova Prnova, M.; Stefek, M.; Omelka, R. The Effects of Prolonged Treatment with Cemtirestat on Bone Parameters Reflecting Bone Quality in Non-Diabetic and Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, S.; Conte, C. Bone Health in Diabetes and Prediabetes. World J. Diabetes 2019, 10, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.; Poundarik, A.A.; Sroga, G.E.; Vashishth, D. Structural Role of Osteocalcin and Its Modification in Bone Fracture. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2023, 10, 011410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, J.L.; Bakker, A.D.; Luyten, F.P.; Verschueren, P.; Lems, W.F.; Klein-Nulend, J.; Bravenboer, N. Systemic Inflammation Affects Human Osteocyte-Specific Protein and Cytokine Expression. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2016, 98, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Hu, K.-S.; Yang, H.-L. Roles of TNF-α, GSK-3β and RANKL in the Occurrence and Development of Diabetic Osteoporosis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11995–12004. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-de-Diego, C.; Pedrazza, L.; Pimenta-Lopes, C.; Martinez-Martinez, A.; Dahdah, N.; Valer, J.A.; Garcia-Roves, P.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. NRF2 Function in Osteocytes Is Required for Bone Homeostasis and Drives Osteocytic Gene Expression. Redox Biol. 2021, 40, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.L.; Abrahamsen, B.; Napoli, N.; Akesson, K.; Chandran, M.; Eastell, R.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G.; Josse, R.; Kendler, D.L.; Kraenzlin, M.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Bone Fragility in Diabetes: An Emerging Challenge. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 2585–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, D.; Gu, X.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Barkema, H.W.; Han, B. Chlorogenic Acid Promotes the Nrf2/HO-1 Anti-Oxidative Pathway by Activating P21Waf1/Cip1 to Resist Dexamethasone-Induced Apoptosis in Osteoblastic Cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 137, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Fu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, P.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, D. A Narrative Review of Diabetic Bone Disease: Characteristics, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1052592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, P.; De Rosa, C.; D’Angelo, S. Polyphenols and Bone Health: A Comprehensive Review of Their Role in Osteoporosis Prevention and Treatment. Molecules 2025, 30, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Babikova, M.; Mondockova, V.; Blahova, J.; Kovacova, V.; Omelka, R. The Role of Macronutrients, Micronutrients and Flavonoid Polyphenols in the Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Sarocka, A.; Penzes, N.; Biro, R.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Sevcikova, A.; Ciernikova, S.; Omelka, R. Protective Role of Dietary Polyphenols in the Management and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2025, 17, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, M.; Tenore, G.C.; Tartaglione, L.; Carmela, D.; Novellino, E.; Ciminiello, P. (1S,3R,4S,5R)5-O-Caffeoylquinic Acid: Isolation, Stereo-Structure Characterization and Biological Activity. Food Chem. 2015, 178, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkonjić, Z.; Nadjpal, J.; Beara, I.; Šibul, F.; Knezevic, P.; Lesjak, M.; Mimica-Dukic, N. Fresh Fruits and Jam of Sorbus domestica L. and Sorbus Intermedia (Ehrh.) Pers.: Phenolic Profiles, Antioxidant Action and Antimicrobial Activity. Bot. Serbica 2019, 43, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ognyanov, M.; Denev, P.; Petkova, N.; Petkova, Z.; Stoyanova, M.; Zhelev, P.; Matev, G.; Teneva, D.; Georgiev, Y. Nutrient Constituents, Bioactive Phytochemicals, and Antioxidant Properties of Service Tree (Sorbus domestica L.) Fruits. Plants 2022, 11, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-Y.; Tang, C.-H.; Ho, T.-L.; Wang, W.-L.; Yao, C.-H. Chlorogenic Acid Prevents Ovariectomized-Induced Bone Loss by Facilitating Osteoblast Functions and Suppressing Osteoclast Formation. Aging 2024, 16, 4832–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, H.B.; Wu, J.B.; Lin, W.C. (−)-Epicatechin 3-O-β-D-Allopyranoside Prevent Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss in Mice by Suppressing RANKL-Induced NF-κB and NFATc-1 Signaling Pathways. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-A.; Song, H.S.; Kwon, J.E.; Baek, H.J.; Koo, H.J.; Sohn, E.-H.; Lee, S.R.; Kang, S.C. Protocatechuic Acid Attenuates Trabecular Bone Loss in Ovariectomized Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 7280342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-H.; Jang, J.-W.; Lee, J.-K.; Park, C.-K. Rutin Improves Bone Histomorphometric Values by Reduction of Osteoclastic Activity in Osteoporosis Mouse Model Induced by Bilateral Ovariectomy. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2020, 63, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nor Muhamad, M.L.; Ekeuku, S.O.; Wong, S.-K.; Chin, K.-Y. A Scoping Review of the Skeletal Effects of Naringenin. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Yao, B.; Liu, G.; Fang, J. Polyphenols as Potential Preventers of Osteoporosis: A Comprehensive Review on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects, Molecular Mechanisms, and Signal Pathways in Bone Metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 123, 109488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palierse, E.; Masse, S.; Laurent, G.; Le Griel, P.; Mosser, G.; Coradin, T.; Jolivalt, C. Synthesis of Hybrid Polyphenol/Hydroxyapatite Nanomaterials with Anti-Radical Properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Shao, H.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, C.Y.; Li, Q. Mechanism and Effects of Polyphenol Derivatives for Modifying Collagen. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 4272–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, L. Naringin Promotes Osteogenic Potential in Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Mediation of miR-26a/Ski Axis. Bone Rep. 2024, 23, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniakova, M.; Penzes, N.; Bíro, R.; Sarocka, A.; Kováčová, V.; Mondockova, V.; Ciernikova, S.; Omelka, R. Sea Buckthorn and Its Flavonoids Isorhamnetin, Quercetin, and Kaempferol Favorably Influence Bone and Breast Tissue Health. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1462823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raigón Jiménez, M.D.; García-Martínez, M.D.; Esteve Ciudad, P.; Fukalova Fukalova, T. Nutritional, Bioactive, and Volatile Characteristics of Two Types of Sorbus domestica Undervalued Fruit from Northeast of Iberian Peninsula, Spain. Molecules 2024, 29, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, M.; Zuzolo, D.; Prigioniero, A.; Ranauda, M.A.; Scarano, P.; Tienda-Parrilla, M.; Hernandez-Lao, T.; Jorrín-Novo, J.; Guarino, C. Changes in the Proteomics and Metabolomics Profiles of Cormus domestica (L.) Fruits during the Ripening Process. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Faliva, M.A.; Peroni, G.; Infantino, V.; Gasparri, C.; Iannello, G.; Perna, S.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; Tartara, A. Pivotal Role of Boron Supplementation on Bone Health: A Narrative Review. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 62, 126577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicka, I.; Kiewlicz, J.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Gliszczyńska-Świgło, A. Selected Dried Fruits as a Source of Nutrients. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majić, B.; Šola, I.; Likić, S.; Cindrić, I.J.; Rusak, G. Characterisation of Sorbus domestica L. Bark, Fruits and Seeds: Nutrient Composition and Antioxidant Activity. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 53, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourassa, M.W.; Abrams, S.A.; Belizán, J.M.; Boy, E.; Cormick, G.; Quijano, C.D.; Gibson, S.; Gomes, F.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Humphrey, J.; et al. Interventions to Improve Calcium Intake through Foods in Populations with Low Intake. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2022, 1511, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpi e Silva, N.; Mazzafera, P.; Cesarino, I. Should I Stay or Should I Go: Are Chlorogenic Acids Mobilized towards Lignin Biosynthesis? Phytochemistry 2019, 166, 112063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termentzi, A.; Kefalas, P.; Kokkalou, E. LC-DAD-MS (ESI+) Analysis of the Phenolic Content of Sorbus domestica Fruits in Relation to Their Maturity Stage. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termentzi, A.; Kefalas, P.; Kokkalou, E. Antioxidant Activities of Various Extracts and Fractions of Sorbus Domestica Fruits at Different Maturity Stages. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esin, E. The Effect of Maturity, Storage Duration, and Conditions on Service Tree (Sorbus domestica L.) Fruit Vinegars: Physicochemical, Phytochemical, and Anti-Diabetic Properties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, S.Z.; Qvist, R.; Kumar, S.; Batumalaie, K.; Ismail, I.S.B. Molecular Mechanisms of Diabetic Retinopathy, General Preventive Strategies, and Novel Therapeutic Targets. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 801269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wianowska, D.; Gil, M. Recent Advances in Extraction and Analysis Procedures of Natural Chlorogenic Acids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Mao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J. Research Advances in the Synthesis, Metabolism, and Function of Chlorogenic Acid. Foods 2025, 14, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M.; Hejazi, V.; Abbas, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Khan, G.J.; Shumzaid, M.; Ahmad, F.; Babazadeh, D.; FangFang, X.; Modarresi-Ghazani, F.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid (CGA): A Pharmacological Review and Call for Further Research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 97, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Tian, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X. Chlorogenic Acid: A Comprehensive Review of the Dietary Sources, Processing Effects, Bioavailability, Beneficial Properties, Mechanisms of Action, and Future Directions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3130–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Han, B. Osteogenic Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid and Its Application in Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1396354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.P.; Lin, S.J.; Wan, W.B.; Zuo, H.L.; Yao, F.F.; Ruan, H.B.; Xu, J.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.C.; Wen, S.Y.; et al. Chlorogenic Acid Prevents Osteoporosis by Shp2/PI3K/Akt Pathway in Ovariectomized Rats. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Dai, W. Chlorogenic Acid Mitigates Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis via Modulation of HER2/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. J. Integr. Med. 2025, 23, 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, X. Mechanism of Chlorogenic Acid Treatment on Femoral Head Necrosis and Its Protection of Osteoblasts. Biomed. Rep. 2016, 5, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Tokuda, H.; Kuroyanagi, G.; Kainuma, S.; Ohguchi, R.; Fujita, K.; Matsushima-Nishiwaki, R.; Kozawa, O.; Otsuka, T. Amplification by (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate and Chlorogenic Acid of TNF-α-Stimulated Interleukin-6 Synthesis in Osteoblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 36, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.C.; Lee, C.; Kim, J.-Y.; Oh, H.M.; So, H.-S.; Lee, M.S.; Rho, M.C.; Oh, J. Chlorogenic Acid Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation and Bone Resorption by Down-Regulation of Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand-Induced Nuclear Factor of Activated T Cells C1 Expression. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.-S.; Lee, C.H.; Ko, M.S.; Choi, J.Y.; Hwang, K.W.; Park, S.-Y. Isolation of Osteoblastic Differentiation-Inducing Constituents from Peanut Sprouts and Development of Optimal Extraction Method. Separations 2023, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-R.; Wankhade, U.D.; Alund, A.W.; Blackburn, M.L.; Shankar, K.; Lazarenko, O.P. 3-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)-Propionic Acid (PPA) Suppresses Osteoblastic Cell Senescence to Promote Bone Accretion in Mice. JBMR Plus 2019, 3, e10201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Lazarenko, O.P.; Chen, J.-R. Hippuric Acid and 3-(3-Hydroxyphenyl) Propionic Acid Inhibit Murine Osteoclastogenesis through RANKL-RANK Independent Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folwarczna, J.; Pytlik, M.; Zych, M.; Cegieła, U.; Nowinska, B.; Kaczmarczyk-Sedlak, I.; Sliwinski, L.; Trzeciak, H.; Trzeciak, H.I. Effects of Caffeic and Chlorogenic Acids on the Rat Skeletal System. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 682–693. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, S.; Wang, K.; Luo, J. Analysis of Anti-Osteoporosis Function of Chlorogenic Acid by Gene Microarray Profiling in Ovariectomy Rat Model. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Kim, H.H.; Bang, J.S.; Jung, T.W.; Park, T.; Park, J.; Kim, U.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, J.H. P-Coumaric Acid Stimulates Longitudinal Bone Growth through Increasing the Serum Production and Expression Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 in Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 505, 1103–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folwarczna, J.; Zych, M.; Burczyk, J.; Trzeciak, H.; Trzeciak, H.I. Effects of Natural Phenolic Acids on the Skeletal System of Ovariectomized Rats. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshan, H.; Nikpayam, O.; Sedaghat, M.; Sohrab, G. Effects of Green Coffee Extract Supplementation on Anthropometric Indices, Glycaemic Control, Blood Pressure, Lipid Profile, Insulin Resistance and Appetite in Patients with the Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Mittal, M.; Ali Mahdi, A.; Awasthi, V.; Kumar, P.; Goel, A.; Banik, S.P.; Chakraborty, S.; Rungta, M.; Bagchi, M.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of a Novel, Patented Green Coffee Bean Extract (GCB70®), Enriched in 70% Chlorogenic Acid, in Overweight Individuals. J. Am. Nutr. Assoc. 2024, 43, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrantelli, V.; Vasto, S.; Alongi, A.; Sabatino, L.; Baldassano, D.; Caldarella, R.; Gagliano, R.; Di Rosa, L.; Consentino, B.B.; Vultaggio, L.; et al. Boosting Plant Food Polyphenol Concentration by Saline Eustress as Supplement Strategies for the Prevention of Metabolic Syndrome: An Example of Randomized Interventional Trial in the Adult Population. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1288064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Herrador, S.; Corral-Sarasa, J.; González-García, P.; Morillas-Morota, Y.; Olivieri, E.; Jiménez-Sánchez, L.; Díaz-Casado, M.E. Natural Hydroxybenzoic and Hydroxycinnamic Acids Derivatives: Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Applications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiong, H.; Li, Q.; He, L.; Weng, H.; Ling, W.; Wang, D. Protocatechuic Acid from Chicory Is Bioavailable and Undergoes Partial Glucuronidation and Sulfation in Healthy Humans. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3071–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadena-Iñiguez, J.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Sánchez-Flores, N.; Salazar-Aguilar, S.; Soto-Hernández, R.M.; Riviello-Flores, M.d.L.L.; Macías-Zaragoza, V.M.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I. The Cancer-Protective Potential of Protocatechuic Acid: A Narrative Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Zetina, S.M.; Gonzalez-Manzano, S.; Perez-Alonso, J.J.; Gonzalez-Paramas, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C. Preparation and Characterization of Protocatechuic Acid Sulfates. Molecules 2019, 24, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; He, Y.; Luo, C.; Feng, B.; Ran, F.; Xu, H.; Ci, Z.; Xu, R.; Han, L.; Zhang, D. New Progress in the Pharmacology of Protocatechuic Acid: A Compound Ingested in Daily Foods and Herbs Frequently and Heavily. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.L.; Chen, P.; D’lIma, D. Protocatechuic Acid Induces Expression of Osteogenic Genes in Human Osteoblast Cultures: Implications for the Treatment of Osteoporosis and Fractures. J. Orthop. Sports Med. 2025, 7, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Feng, W.; Wu, P.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Liu, W.; Lv, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J. Exploration the Mechanism Underlying Protocatechuic Acid in Treating Osteoporosis by HIF-1 Pathway Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Experimental Verification. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 122, 106531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-X.; Wu, T.-Y.; Xu, B.-B.; Xu, X.-Y.; Chen, H.-G.; Li, X.-Y.; Wang, G. Protocatechuic Acid Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation and Stimulates Apoptosis in Mature Osteoclasts. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 82, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, D.; Yang, H. Protocatechuic Acid Attenuates Anterior Cruciate Ligament Transection-Induced Osteoarthritis by Suppressing Osteoclastogenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Piza, A.; An, Y.J.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.-B.; Choi, J.-S.; Lee, S.-J. Protocatechuic Acid Enhances Osteogenesis, but Inhibits Adipogenesis in C3H10T1/2 and 3T3-L1 Cells. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, S.; Tong, G.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S. Protocatechuic Acid as a Potential Phytomedicine in a TCM Herbal Extract Mitigates Alcohol-Induced Osteoporosis. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 20, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-H.; Hwang, I.-G.; Lee, Y.-M. Effects of Anthocyanin Supplementation on Blood Lipid Levels: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1207751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, R.; Xia, M. Purified Anthocyanin Supplementation Reduces Dyslipidemia, Enhances Antioxidant Capacity, and Prevents Insulin Resistance in Diabetic Patients. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, I.; Fabjan, N.; Yasumoto, K. Rutin Content in Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Esculentum Moench) Food Materials and Products. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullón, B.; Lú-Chau, T.A.; Moreira, M.T.; Lema, J.M.; Eibes, G. Rutin: A Review on Extraction, Identification and Purification Methods, Biological Activities and Approaches to Enhance Its Bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. SPJ 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauludin, R.; Müller, R.H.; Keck, C.M. Kinetic Solubility and Dissolution Velocity of Rutin Nanocrystals. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 36, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, A.; Yu, C.; Zang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Deng, X.; Guan, Y. Synthesis and Evaluation of Rutin–Hydroxypropyl β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes Embedded in Xanthan Gum-Based (HPMC-g-AMPS) Hydrogels for Oral Controlled Drug Delivery. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriti, M.; Varoni, E.M.; Vitalini, S. Bioactive Compounds in Health and Disease—Focus on Rutin. Bioact. Compd. Health Dis.—Online 2023, 6, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; Hsiu, S.-L.; Wen, K.-C.; Lin, S.-P.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Hou, Y.-C.; Chao, P.-D.L. Bioavailability and Metabolic Pharmacokinetics of Rutin and Quercetin in Rats. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muvhulawa, N.; Dludla, P.V.; Ziqubu, K.; Mthembu, S.X.H.; Mthiyane, F.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E. Rutin Ameliorates Inflammation and Improves Metabolic Function: A Comprehensive Analysis of Scientific Literature. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Xu, X. Rutin Promotes the Formation and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cell Sheets In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 2289–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.; Park, H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Oh, H.I.; Hwang, H.S.; Kim, H.H. Effects of Watercress Containing Rutin and Rutin Alone on the Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Osteoblast-like MG-63 Cells. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2014, 18, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yin, W.; Xu, C.; Feng, Y.; Huang, X.; Hao, J.; Zhu, C. Rutin Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) by Increasing ECM Deposition and Inhibiting P53 Expression. Aging 2024, 16, 3583–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyung, T.-W.; Lee, J.-E.; Shin, H.-H.; Choi, H.-S. Rutin Inhibits Osteoclast Formation by Decreasing Reactive Oxygen Species and TNF-α by Inhibiting Activation of NF-κB. Exp. Mol. Med. 2008, 40, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.-L.; Huo, X.-C.; Wang, J.-H.; Wang, D.-P.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Liu, B.; Xu, L.-L. Rutin Prevents the Ovariectomy-Induced Osteoporosis in Rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 1911–1917. [Google Scholar]

- Albaqami, F.F.; Althurwi, H.N.; Alharthy, K.M.; Hamad, A.M.; Awartani, F.A. Rutin Gel with Bone Graft Accelerates Bone Formation in a Rabbit Model by Inhibiting MMPs and Enhancing Collagen Activities. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyar, H.; Moradi, L.; Zaman, F.; Zare Javid, A. The Effects of Rutin Flavonoid Supplement on Glycemic Status, Lipid Profile, Atherogenic Index of Plasma, Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), Some Serum Inflammatory, and Oxidative Stress Factors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Phytother. Res. PTR 2023, 37, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazyar, H.; Zare Javid, A.; Ahangarpour, A.; Zaman, F.; Hosseini, S.A.; Zohoori, V.; Aghamohammadi, V.; Yazdanfar, S.; Ghasemi Deh Cheshmeh, M. The Effects of Rutin Supplement on Blood Pressure Markers, Some Serum Antioxidant Enzymes, and Quality of Life in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Compared with Placebo. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1214420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherr, R.E.; Keen, C.L.; Zidenberg-Cherr, S. Nutrition and Health Info Sheet: Catechins and Epicatechins; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bordin Davidson, C.; Forrati Machado, É.; Kolinski Machado, A.; Valente de Souza, D.; Pappis, L.; Kolinski Cossettin Bonazza, G.; Ulrich Bick, D.L.; Schuster Montagner, T.R.; Gündel, A.; Zanella da Silva, I.; et al. Epicatechin-Loaded Nanocapsules: Development, Physicochemical Characterization, and NLRP3 Inflammasome-Targeting Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Biology 2025, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hassan, Y.I.; Liu, R.; Mats, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, C.; Tsao, R. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Absorption of Aglycone and Glycosidic Flavonoids in a Caco-2 BBe1 Cell Model. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 10782–10793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, M.; Olszewska, M.A.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Nowak, P.; Owczarek, A. Sorbus domestica Leaf Extracts and Their Activity Markers: Antioxidant Potential and Synergy Effects in Scavenging Assays of Multiple Oxidants. Molecules 2019, 24, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Buendia, E.; González-Gómez, G.H.; Maciel-Cerda, A.; González-Torres, M. Epicatechin Derivatives in Tissue Engineering: Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Regenerative Use. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2025, 31, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, C.F.; Moreno-Ulloa, A.; Shiva, S.; Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Taub, P.R.; Su, Y.; Ceballos, G.; Dugar, S.; Schreiner, G.; Villarreal, F. Pharmacokinetic, Partial Pharmacodynamic and Initial Safety Analysis of (-)-Epicatechin in Healthy Volunteers. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Ottaviani, J.I.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Schroeter, H.; Crozier, A. Absorption, Metabolism, Distribution and Excretion of (-)-Epicatechin: A Review of Recent Findings. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 61, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Ruiz, A.G.; Ganem, A.; Olivares-Corichi, I.M.; García-Sánchez, J.R. Lecithin–Chitosan–TPGS Nanoparticles as Nanocarriers of (−)-Epicatechin Enhanced Its Anticancer Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34773–34782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Lara, I.; Calzada-Mendoza, C.C.; Mera-Jiménez, E.; Romero López, E.; Amaya-Espinoza, J.L.; Parra-Barrera, A.; Gutiérrez-Iglesias, G. Phytochemical Properties of (-)-Epicatechin Promotes Bone Regeneration Inducing Osteogenic Markers Expression BMP2, SPARC, and RUNX2 in Mesenchymal Stem Cells In Vitro. J. Med. Food 2025, 28, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Tian, J.; Cai, K.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Su, Y.; Cui, L. Promoting Osteoblast Differentiation by the Flavanes from Huangshan Maofeng Tea Is Linked to a Reduction of Oxidative Stress. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, C.J.; Chou, S.; Kim, E.; Ratnarajah, D.; Cook, N.R.; Clar, A.; Sesso, H.D.; Manson, J.E.; LeBoff, M.S. Effects of Cocoa Extract Supplementation and Multivitamin/Multimineral Supplements on Self-Reported Fractures in the Cocoa Supplement and Multivitamins Outcomes Study Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2025, 40, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dower, J.I.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Gijsbers, L.; Zock, P.L.; Kromhout, D.; Hollman, P.C.H. Effects of the Pure Flavonoids Epicatechin and Quercetin on Vascular Function and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Salmeán, G.; Ortiz-Vilchis, P.; Vacaseydel, C.M.; Rubio-Gayosso, I.; Meaney, E.; Villarreal, F.; Ramírez-Sánchez, I.; Ceballos, G. Acute Effects of an Oral Supplement of (−)-Epicatechin on Postprandial Fat and Carbohydrate Metabolism in Normal and Overweight Subjects. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.J.; Sampson, M.; Potter, J.; Dhatariya, K.; Kroon, P.A.; Cassidy, A. Chronic Ingestion of Flavan-3-Ols and Isoflavones Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Lipoprotein Status and Attenuates Estimated 10-Year CVD Risk in Medicated Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes: A 1-Year, Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafah, A.; Rehman, M.U.; Mir, T.M.; Wali, A.F.; Ali, R.; Qamar, W.; Khan, R.; Ahmad, A.; Aga, S.S.; Alqahtani, S.; et al. Multi-Therapeutic Potential of Naringenin (4′,5,7-Trihydroxyflavonone): Experimental Evidence and Mechanisms. Plants 2020, 9, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Trevethan, M.; Wang, S.; Zhao, L. Beneficial Effects of Citrus Flavanones Naringin and Naringenin and Their Food Sources on Lipid Metabolism: An Update on Bioavailability, Pharmacokinetics, and Mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 104, 108967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Peng, W.; Yang, C.; Zou, W.; Liu, M.; Wu, H.; Fan, L.; Li, P.; Zeng, X.; Su, W. Pharmacokinetics and Metabolism of Naringin and Active Metabolite Naringenin in Rats, Dogs, Humans, and the Differences Between Species. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Zheng, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, W.; Su, W. Microbial Metabolism of Naringin and the Impact on Antioxidant Capacity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, G.; Hu, J.; Li, D.; Fu, X.; Yang, W.; Yang, F. Naringin Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation and Ameliorates Osteoporosis in Ovariectomized Mice. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, N.; Woodard, K.; Ramaraju, R.; Greenway, F.L.; Coulter, A.A.; Rebello, C.J. Naringenin Increases Insulin Sensitivity and Metabolic Rate: A Case Study. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heino, T.J.; Chagin, A.S.; Sävendahl, L. The Novel Estrogen Receptor G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 30 Is Expressed in Human Bone. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 197, R1–R6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, J.; Martinoli, M.-G. Considerations for the Use of Polyphenols as Therapies in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; McDougall, G.J.; Alegría, A.; Alminger, M.; Arrigoni, E.; Aura, A.-M.; Brito, C.; Cilla, A.; El, S.N.; Karakaya, S.; et al. Mind the Gap—Deficits in Our Knowledge of Aspects Impacting the Bioavailability of Phytochemicals and Their Metabolites—A Position Paper Focusing on Carotenoids and Polyphenols. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.B.; Styring, A.K.; McCullagh, J.S.O. Polyphenols: Bioavailability, Microbiome Interactions and Cellular Effects on Health in Humans and Animals. Pathogens 2022, 11, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behne, S.; Franke, H.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Risk Assessment of Chlorogenic and Isochlorogenic Acids in Coffee By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M. Cellular Targets for the Beneficial Actions of Tea Polyphenols. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1642S–1650S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruga, M.; Tomac, I. Electrochemical Behaviour of Some Chlorogenic Acids and Their Characterization in Coffee by Square-Wave Voltammetry. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2014, 9, 6134–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wei, M.; Yan, H.; Zhu, H. Chlorogenic Acid Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Through Wnt Signaling. Stem Cells Dev. 2021, 30, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, A.P.; Ardani, I.G.A.W.; Sitalaksmi, R.M.; Ramadhani, N.F.; Rachmayanti, D.; Kumala, D.; Kharisma, V.D.; Rahmadani, D.; Puspitaningrum, M.S.; Rizqianti, Y.; et al. Anti-Peri-Implantitis Bacteria’s Ability of Robusta Green Coffee Bean (Coffea canephora) Ethanol Extract: An In Silico and In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2023, 17, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán, J.L.; Sanli, N.; Fonrodona, G.; Barrón, D.; Özkan, G.; Barbosa, J. Spectrophotometric, Potentiometric and Chromatographic pKa Values of Polyphenolic Acids in Water and Acetonitrile–Water Media. Anal. Chim. Acta 2003, 484, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornard, J.-P.; Lapouge, C.; André, E. pH Influence on the Complexation Site of Al(III) with Protocatechuic Acid. A Spectroscopic and Theoretical Approach. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 108, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.L.; Chen, P.; D’Lima, D. Protocatechuic Acid Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Impact on Bone Metabolism, Osteoporosis and Fractures. J. Orthop. Sports Med. 2025, 7, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.S.; Cho, Y.H.; Lee, E.J. G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor-1 Is Involved in the Protective Effect of Protocatechuic Aldehyde against Endothelial Dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehenkari, P.; Hentunen, T.A.; Laitala-Leinonen, T.; Tuukkanen, J.; Väänänen, H.K. Carbonic Anhydrase II Plays a Major Role in Osteoclast Differentiation and Bone Resorption by Effecting the Steady State Intracellular pH and Ca2+. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 242, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.S.; Soliman, G.M. Rutin Nanocrystals with Enhanced Anti-Inflammatory Activity: Preparation and Ex Vivo/In Vivo Evaluation in an Inflammatory Rat Model. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-W.; Ma, B.; Zi, Y.; Xiang, L.-B.; Han, T.-Y. Effects of Rutin on Osteoblast MC3T3-E1 Differentiation, ALP Activity and Runx2 Protein Expression. Eur. J. Histochem. EJH 2021, 65, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, M.; Xu, W.; Zou, L.; Ye, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Luo, J. Rutin Inhibited the Advanced Glycation End Products-Stimulated Inflammatory Response and Extra-Cellular Matrix Degeneration via Targeting TRAF-6 and BCL-2 Proteins in Mouse Model of Osteoarthritis. Aging 2021, 13, 22134–22147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouamnina, A.; Alahyane, A.; Elateri, I.; Ouhammou, M.; Abderrazik, M. In Vitro and Molecular Docking Studies of Antiglycation Potential of Phenolic Compounds in Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Fruit: Exploring Local Varieties in the Food Industry. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Bridge, B.; Lévèques, A.; Li, H.; Bertschy, E.; Patin, A.; Actis-Goretta, L. Modulation of (–)-Epicatechin Metabolism by Coadministration with Other Polyphenols in Caco-2 Cell Model. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, I.J.S.; Barbalho, S.M.; Andreo, J.C.; Zutin, T.L.M.; Laurindo, L.F.; Rodrigues, V.D.; Araújo, A.C.; Guiguer, E.L.; Direito, R.; Pomini, K.T.; et al. Exploring the Impact of Catechins on Bone Metabolism: A Comprehensive Review of Current Research and Future Directions. Metabolites 2024, 14, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila-Avilés, R.D.; Bahena-Culhuac, E.; Hernández-Hernández, J.M. (-)-Epicatechin Metabolites as a GPER Ligands: A Theoretical Perspective. Mol. Divers. 2025, 29, 2099–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermeo, S.; Al Saedi, A.; Vidal, C.; Khalil, M.; Pang, M.; Troen, B.R.; Myers, D.; Duque, G. Treatment with an Inhibitor of Fatty Acid Synthase Attenuates Bone Loss in Ovariectomized Mice. Bone 2019, 122, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilpa, V.S.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Pandey, V.K.; Dar, A.H.; Ayaz Mukarram, S.; Harsányi, E.; Kovács, B. Phytochemical Properties, Extraction, and Pharmacological Benefits of Naringin: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Kulkarni, Y.A.; Wairkar, S. Pharmacokinetic, Pharmacodynamic and Formulations Aspects of Naringenin: An Update. Life Sci. 2018, 215, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-X.; Du, S.-X.; Liu, D.-Z.; Hu, Q.-X.; Yu, G.-Y.; Wu, C.-C.; Zheng, G.-Z.; Xie, D.; Li, X.-D.; Chang, B. Naringin Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells by Up-Regulating Foxc2 Expression via the IHH Signaling Pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 5098–5107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cui, X.; Wang, D.; Kang, B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X. Mechanistic Insights into the Anti-Osteoporotic Effects of Naringin via Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking Studies. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2024, 5, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alldritt, I.; Whitham-Agut, B.; Sipin, M.; Studholme, J.; Trentacoste, A.; Tripp, J.A.; Cappai, M.G.; Ditchfield, P.; Devièse, T.; Hedges, R.E.M.; et al. Metabolomics Reveals Diet-Derived Plant Polyphenols Accumulate in Physiological Bone. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.T.T.; Yoda, T.; Chahal, B.; Morita, M.; Takagi, M.; Vestergaard, M.C. Structure-Dependent Interactions of Polyphenols with a Biomimetic Membrane System. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Biomembr. 2014, 1838, 2670–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, N.; Cassinelli, C.; Torre, E.; Morra, M.; Iviglia, G. Improvement of the Physical Properties of Guided Bone Regeneration Membrane from Porcine Pericardium by Polyphenols-Rich Pomace Extract. Materials 2019, 12, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; de Luna-Bertos, E.; Illescas-Montes, R.; Arnett, T.R.; Ruiz, C.; García-Martínez, O. Influence of pH on Osteoclasts Treated with Zoledronate and Alendronate. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Xie, Y.; Cao, H.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J. Fetal Bovine Serum Influences the Stability and Bioactivity of Resveratrol Analogues: A Polyphenol-Protein Interaction Approach. Food Chem. 2017, 219, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, D.; Doldur, A.; Cavdar, D.; Ozkan, G.; Ceylan, F.D. Current Methodologies for Assessing Protein–Phenolic Interactions. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P.; Sardar, P.S.; Roy, P.; Dasgupta, S.; Bose, A. Investigation on the Interaction of Rutin with Serum Albumins: Insights from Spectroscopic and Molecular Docking Techniques. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2018, 183, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, S.; Saranya, V.; Shankar, R.; Sasirekha, V. Structural Exploration of Interactions of (+) Catechin and (−) Epicatechin with Bovine Serum Albumin: Insights from Molecular Dynamics and Spectroscopic Methods. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 348, 118026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Jin, X.; Liu, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; et al. Evaluation the Binding of Chlorogenic Acid with Bovine Serum Albumin: Spectroscopic Methods, Electrochemical and Molecular Docking. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 291, 122289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Fu, J.; Yang, H.; Ge, W.; Shi, Y.; Lee, Y.; Huang, C. High Affinity of Protocatechuic Acid to Human Serum Albumin and Modulatory Effects against Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Alveolar Epithelial Cells: Modulation of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Xu, Z.; Liang, Z.; Su, J.; Huang, J.; Li, B. Investigation of the Interaction of Naringin Palmitate with Bovine Serum Albumin: Spectroscopic Analysis and Molecular Docking. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y. The Effect of Non-Covalent Interaction of Chlorogenic Acid with Whey Protein and Casein on Physicochemical and Radical-Scavenging Activity of in Vitro Protein Digests. Food Chem. 2018, 268, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sęczyk, Ł.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Świeca, M. Influence of Phenolic-Food Matrix Interactions on In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Selected Phenolic Compounds and Nutrients Digestibility in Fortified White Bean Paste. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Świeca, M.; Kapusta, I.; Sip, A.; Ochmian, I. Comparative Assessment of Polyphenol Stability, Bioactivity, and Digestive Availability in Purified Compounds and Fruit Extracts from Four Black Chokeberry Cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Jahan, N.; Rahman, K.U.; Zafar, F.; Ashraf, M. Synergistic Interactions of Polyphenols & Their Effect on Antiradical Potential. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 30, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada-Vázquez, S.; Eseberri, I.; Les, F.; Pérez-Matute, P.; Herranz-López, M.; Atgié, C.; Lopez-Yus, M.; Aranaz, P.; Oteo, J.A.; Escoté, X.; et al. Polyphenols and Metabolism: From Present Knowledge to Future Challenges. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 80, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Carvalho, A.; Kim, H.-N.; Almeida, M. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Bone Cell Physiology and Pathophysiology. Bone Rep. 2023, 19, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palafox-Carlos, H.; Gil-Chávez, J.; Sotelo-Mundo, R.R.; Namiesnik, J.; Gorinstein, S.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Antioxidant Interactions between Major Phenolic Compounds Found in ‘Ataulfo’ Mango Pulp: Chlorogenic, Gallic, Protocatechuic and Vanillic Acids. Molecules 2012, 17, 12657–12664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimehdipoor, H.; Shahrestani, R.; Shekarchi, M. Investigating the Synergistic Antioxidant Effects of Some Flavonoid and Phenolic Compounds. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2014, 1, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Habza-Kowalska, E.; Kaczor, A.A.; Żuk, J.; Matosiuk, D.; Gawlik-Dziki, U. Thyroid Peroxidase Activity Is Inhibited by Phenolic Compounds—Impact of Interaction. Molecules 2019, 24, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado-Mercado, G.; de la Rosa, L.A.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E. Effect of Pectin on the Interactions among Phenolic Compounds Determined by Antioxidant Capacity. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1199, 126967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupp, A.B.; Kolb, A.D.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Bussard, K.M. Cancer Metastases to Bone: Concepts, Mechanisms, and Interactions with Bone Osteoblasts. Cancers 2018, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Xiang, D.; Zhu, H.; He, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, R. Dual Role of Autophagy in Bone Metastasis: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Targeting. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2025, 13, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goharpour, S.; Rahimnejad, M.; Najafpour, G.; Farzaei, M.H. Synergistic Effects of the Combination of Quercetin, Naringin, and Rutin on Cervical Cancer: Roles of Apoptosis and Autophagy. J. Food Biochem. 2025, 2025, 9402123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dükel, M. Combination of Naringenin and Epicatechin Sensitizes Colon Carcinoma Cells to Anoikis via Regulation of the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT). Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2022, 19, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.Q.; Tye, C.E.; Stein, G.S.; Lian, J.B. Non-Coding RNAs: Epigenetic Regulators of Bone Development and Homeostasis. Bone 2015, 81, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, F.; Cianferotti, L.; Brandi, M.L. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Bone Biology and Osteoporosis: Can They Drive Therapeutic Choices? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Calle, J.; Sañudo, C.; Sánchez-Verde, L.; García-Renedo, R.J.; Arozamena, J.; Riancho, J.A. Epigenetic Regulation of Alkaline Phosphatase in Human Cells of the Osteoblastic Lineage. Bone 2011, 49, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantomasi, T.; Romagnoli, C.; Palmini, G.; Donati, S.; Falsetti, I.; Miglietta, F.; Aurilia, C.; Marini, F.; Giusti, F.; Brandi, M.L. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Osteoporosis: Molecular Mechanisms Involved and the Relationship with microRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo Vázquez, L.A.; Moreno Becerril, M.Y.; Mora Hernández, E.O.; de León Carmona, G.G.; Aguirre Padilla, M.E.; Chakraborty, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Paul, S. The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in Bone Diseases and Their Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2021, 27, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandes, L.C.; Machado, A.R.T.; Tuttis, K.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Aissa, A.F.; Dévoz, P.P.; Antunes, L.M.G. Caffeic Acid and Chlorogenic Acid Cytotoxicity, Genotoxicity and Impact on Global DNA Methylation in Human Leukemic Cell Lines. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2020, 43, e20190347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, W.; Li, X. Anthocyanin-Mediated Epigenetic Modifications: A New Perspective in Health Promoting and Disease Prevention. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domazetovic, V.; Marcucci, G.; Pierucci, F.; Bruno, G.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Ghelardini, C.; Brandi, M.L.; Iantomasi, T.; Meacci, E.; Vincenzini, M.T. Blueberry Juice Protects Osteocytes and Bone Precursor Cells against Oxidative Stress Partly through SIRT1. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Herrera, I.; Chen, X.; Ramos, S.; Devaraj, S. (-)-Epicatechin Attenuates High-Glucose-Induced Inflammation by Epigenetic Modulation in Human Monocytes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 1369–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Zhong, M.; Chen, Y.; Su, W.; Li, P. Epigenetic Regulation by Naringenin and Naringin: A Literature Review Focused on the Mechanisms Underlying Its Pharmacological Effects. Fitoterapia 2025, 181, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, J.-H.; Chung, M.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Nam, T.-G.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, J.-T.; Choi, H.-K. 3,4-Dihydroxytoluene, a Metabolite of Rutin, Suppresses the Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Mice by Inhibiting P300 Histone Acetyltransferase Activity. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, J.; Fan, Q. Naringin Promotes Differentiation of Bone Marrow Stem Cells into Osteoblasts by Upregulating the Expression Levels of microRNA-20a and Downregulating the Expression Levels of PPARγ. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 4759–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Research Type Model | Research Model | Applied Treatment | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | CGA: 0.1–10 μg/mL for 7 days applied with RANKL | ↓ TRAP activity | [29] |

| In vitro | MG-63 murine monocyte cells | CGA: 0.1–10 μg/mL 2 days to assess viability, and 21 days to assess mineralization | ↑ proliferation, ALP activity; ↑ mineralization | [29] |

| In vitro | BMSC | CGA: 0.1–10 μM for 3 and 7 days | ↑ proliferation; ↑ differentiation (ALP activity) | [55] |

| In vitro | MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts | CGA: 50 μM for 60 min prior to TNFα stimulation | ↑ Il-6 mRNA levels | [58] |

| In vitro | MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts | CGA: 50, 100 μM for 3 h in DEX-induced conditions | ↑ viability; ↓ caspase activity; ↓ ROS, mitochondrial apoptosis | [21] |

| In vitro | MLO-Y4 osteocytes like cell line | CGA: 10, 100 μM with prior DEX-treatment | ↑ gene expression of Runx2, Bglap, β-catenin, and Cx43; ↓ ROS, apoptosis rate | [56] |

| In vitro | Mouse BMMs | CGA: 50 μg/mL with RANKL and M-SCF for 4 day (TRAP-staining) and 2 days (gene expression analysis) | ↓ TRAP activity; ↓ Nfatc1 and Trap mRNA levels | [59] |

| In vivo | OVX rats (n = 24) | CGA: 50, 75 mg/day for 8 weeks | ↑ tibial Tb.N, Tb.Th and BV/TV | [29] |

| In vivo | OVX rats (n = 60) | CGA: 27, 45 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks | ↑ total femur BMD, Tb.N, Tb.Th, BV/TV, Conn.D; ↑ALP, osteocalcin | [55] |

| In vivo | OVX rats (n = 18) | CGA: 45 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks | ↑ total femur BMD, Tb.N, Tb.Th, BV/TV, SMI | [64] |

| In vivo | OVX rats (n = 81–90) | CGA: at 100 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | ↑ femur trabeculae width | [63] |

| In vivo | Femoral head necrosis model rats (n = 60) | CGA: 20 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | ↑ femoral head BMD | [57] |

| In vivo | DEX-induced osteoporotic mice (n = 40) | CGA: 0.5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | ↑ femoral Tb.Th, BMD; ↓ femoral Tb.Sp; ↑ ALP, P1NP | [56] |

| In vivo | LPS-induced bone erosion mice (n = not specified) | CGA from Gardenia jasminoides: 10 mg/kg/day for 8 days | ↑ femoral BV/TV, Tb.Th | [59] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with BMI > 25 kg/m2 (n = 33) | green coffee bean extract: 400 mg twice a day for 8 weeks | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↓ FBG; ↓ body weight | [67] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with BMI >25 kg/m2 (n = 105) | GCB70® (70% 5-CQA, 30% 3-CQA): 500 mg twice a day for 12 weeks | ↑ HDL; ↓ FBG, HbA1c; ↓ TSH, LDL | [68] |

| Clinical trial | Healthy participants (n = 42) | Polyphenol-rich lettuce 100 g/day for 12 days | ↑ vitamin D; ↓ LDL, PTH | [69] |

| Research Type Model | Research Model | Applied Treatment | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | Primary human osteoblasts | PCA: 50, 100 μM for 12 days | ↑ SPP1, IBSP, ALPL, BMP6; ↑ IL-1β | [75] |

| In vitro | MC3T3-E1 (preosteoblast cell line) treated with DEX | PCA: 12.5, 25, and 50 μmol/L for 24 h and 7 days | ↑ proliferation; ↑ ALP activity; ↑ SOD, GSH; ↓ ROS, MDA | [76] |

| In vitro | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | PCA: 8 μM for 2 h prior treated with RANKL | ↑ SOD, GPx, GSH; ↓ ROS; ↓ TRAP activity; ↓ Trap, Traf6, c-Src, Mmp9, cathepsin mRNA levels | [77] |

| In vitro | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | PCA: 8 μM for 2 h prior treated with RANKL | ↓ TRAP activity; ↓ NFATc1, NF-κB protein levels | [78] |

| In vitro | Murine C3H10T1/2 MSC cells | PCA: 80 μM for 6- or 9-day in osteogenic induction conditions | ↑ ALP activity; ↑ mineralization; ↑ Runx2, Alpl, Sp7 mRNA levels | [79] |

| In vivo | OVX mice (n = 30) | PCA: 20 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks | ↑ tibial trabecular BMD, Tb.N, and BV/TV; ↓ tibial Tb.Sp; ↑ OPG; ↓ RANKL; ↓ Nfatc1, Traf6 mRNA levels | [31] |

| In vivo | Alcohol-induced osteopenic mice (n = 20) | PCA: 50 mg/kg for 40 days | ↑ tibial trabecular BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N | [80] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with T2DM (n = 58) | Anthocyanin (major metabolite: PCA), 160 g twice a day for 24 weeks | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↓ FBG, TAG; ↓ TNF-α, IL-6 | [82] |

| Research Type Model | Research Model | Applied Treatment | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | PDLSCs | Rutin: 1 × 10−6 mol/L for 3 days proliferation assay, and 7 days for differentiation | ↑ proliferation; ↑ osteogenic differentiation, ALP activity; ↑ COL1A1, ALP, RUNX2 and SPP1 mRNA and protein levels | [91] |

| In vitro | MG-63 human osteosarcoma cell lines | Rutin: 10 and 25 μg/mL in 3, 5, and 7 days for proliferation, collagen synthesis and mineralization, respectively | ↑ proliferation, ALP activity; ↑ collagen production; ↑ mineralization | [92] |

| In vitro | MSCs | Rutin: 50 mg/mL for 24 h | ↑ COL1A1, RUNX2, osteocalcin, osteopontin mRNA and protein levels; ↑ mineralization | [93] |

| In vitro | Mouse bone marrow cells | Rutin: 20 μM for 3 days with M-CSF and RANKL | ↓ TRAP activity; ↓ ROS; ↓ TNF-α | [94] |

| In vivo | OVX mice (n = 30) | Rutin: 50 mg/kg for 4 or 8 weeks | ↑ femoral BV/TV, Tb.Th; ↓ femoral Tb.Sp.; ↓ ALP, CTx; ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α | [32] |

| In vivo | OVX rats (n = 40) | Rutin: 10 mg/kg/day for 3 months | ↑ total femur BMD; ↓ osteocalcin, vitamin D; ↓ IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ | [95] |

| In vivo | Bone defect rabbit model (tooth removal) (n = 6) | Rutin: 2.5 mg mixed with 900 mg of demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft left in for 6 weeks | ↑ COL3A1 mRNA levels; ↓ MMPs mRNA levels | [96] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with T2DM (n = 50) | Rutin: 500 mg/day for 3 months | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↑ HDL; ↓ FBG, HbA1c, INS; ↓ LDL; ↓ IL-6 and MDA | [97] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with T2DM (n = 50) | Rutin: 500 mg/day for 3 months | ↑ SOD, GPx | [98] |

| Research Type Model | Research Model | Applied Treatment | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | RAW264.7 macrophage cell line | ECAP: 50 and 100 μg/mL for 24 h and 5 days, pre-treated with RANKL | ↓ TRAP activity; ↓ MMP9, NFATc1 mRNA and protein levels | [30] |

| In vitro | MSC-hBM | Epicatechin: 1 and 100 µM for 72 h | ↑ RUNX2, SPARC mRNA levels | [107] |

| In vitro | Rat osteoblasts | Epicatechin: 25 and 50 μg/mL, for 48 h, 7 days, and 20 days | ↑ differentiation, ALP activity; ↑ hydroxyapatite formation; ↑ mineralization | [108] |

| In vivo | OVX mice (n = 32) | ECAP: 100 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks | ↑ femoral Tb.N, Tb.Th, BV/TV; ↓ femoral Tb.Sp; ↓ osteocalcin, CTx | [30] |

| Clinical trial | Healthy women (≥65 y) and men (≥60 y) (n = 21,442) | Daily cocoa extra supplement contained a total of 500 mg/day of flavanols including 80 mg/day of epicatechin for 3.6 years (median) | No effect on a risk of incident clinical fracture | [109] |

| Clinical trial | Healthy participants (n = 35) | Epicatechin: 100 mg/day for 4 weeks | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↓ INS | [110] |

| Clinical trial | Participants with (BMI) > 18.5 and <30 kg/m2 (n = 20) | Epicatechin: 1 mg/kg once and after 4 h blood chemistry tests | ↓ plasma glucose, TAG | [111] |

| Clinical trial | Postmenopausal women with T2DM (n = 93) | Flavonoid-enriched chocolate: epicatechin 90 mg combined with flavan-3-ols and isoflavones | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↑ HDL; ↓ INS | [112] |

| Research Type Model | Research Model | Applied Treatment | Obtained Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro | MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts | Naringin: 0.5–1 μM for 24 h, 14 days, and 21 days | ↑ proliferation; ↑ differentiation, ALP activity; ↑ mineralization; ↑ RUNX2, COL1A1, osteopontin mRNA and protein levels | [117] |

| In vivo | OVX mice (n = 40) | Naringin: 30 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks | ↑ femoral BMD, BV/TV, Tb.N, Tb.Th; ↓ femoral Tb.Sp; ↑ P1NP, osteocalcin; ↓ CTx | [117] |

| Clinical trial | Participant with diabetes (n = 1) | Naringin: 150 mg three times daily for 8 weeks | ↑ INS sensitivity; ↓ INS | [118] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Penzes, N.; Omelka, R.; Sarocka, A.; Biro, R.; Kovacova, V.; Mondockova, V.; Martiniakova, M. Therapeutic Effects of the Most Common Polyphenols Found in Sorbus domestica L. Fruits on Bone Health. Nutrients 2026, 18, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020267

Penzes N, Omelka R, Sarocka A, Biro R, Kovacova V, Mondockova V, Martiniakova M. Therapeutic Effects of the Most Common Polyphenols Found in Sorbus domestica L. Fruits on Bone Health. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020267

Chicago/Turabian StylePenzes, Noemi, Radoslav Omelka, Anna Sarocka, Roman Biro, Veronika Kovacova, Vladimira Mondockova, and Monika Martiniakova. 2026. "Therapeutic Effects of the Most Common Polyphenols Found in Sorbus domestica L. Fruits on Bone Health" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020267

APA StylePenzes, N., Omelka, R., Sarocka, A., Biro, R., Kovacova, V., Mondockova, V., & Martiniakova, M. (2026). Therapeutic Effects of the Most Common Polyphenols Found in Sorbus domestica L. Fruits on Bone Health. Nutrients, 18(2), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020267