The Effect of the DASH Diet on the Development of Gestational Hypertension in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Literature Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction Methodology

2.6. Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

2.7. Sensitivity and Subgroup Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Quality Assessment

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. DASH Diet Assessment and Exposure Period

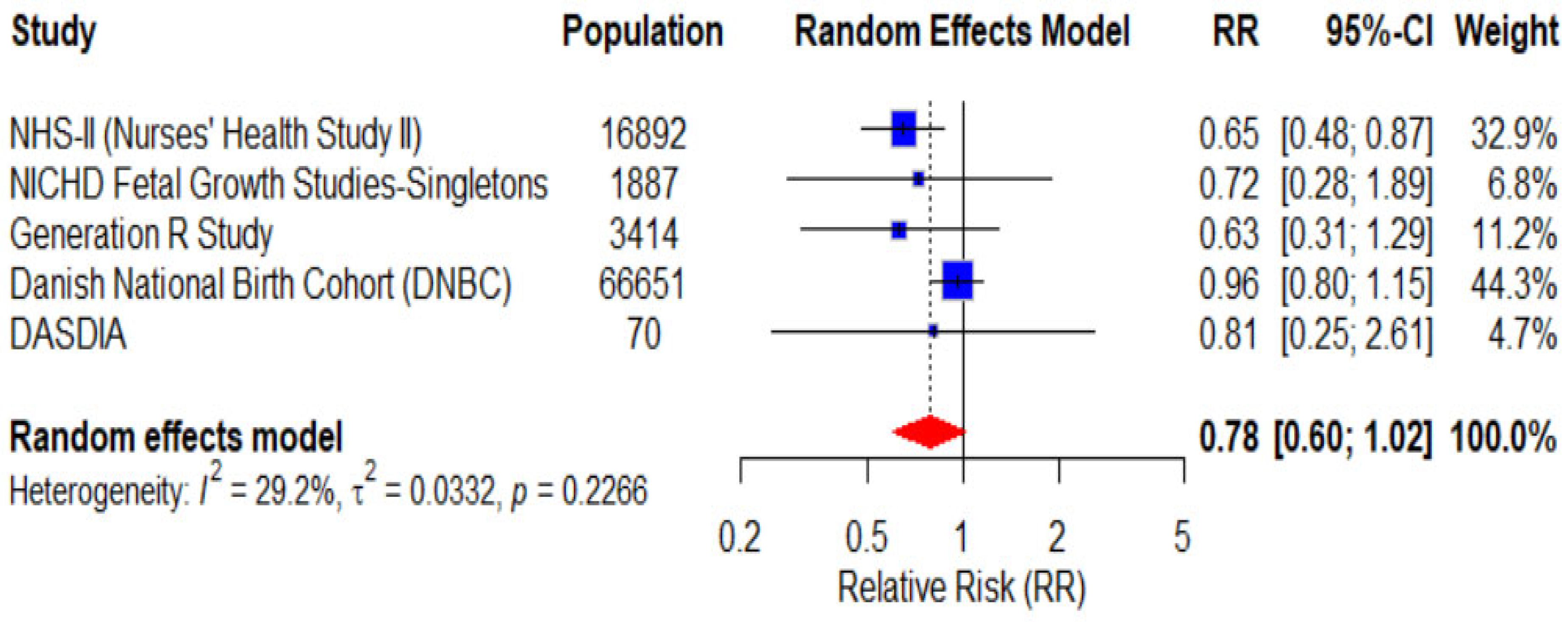

3.5. Gestational Hypertension Incidence

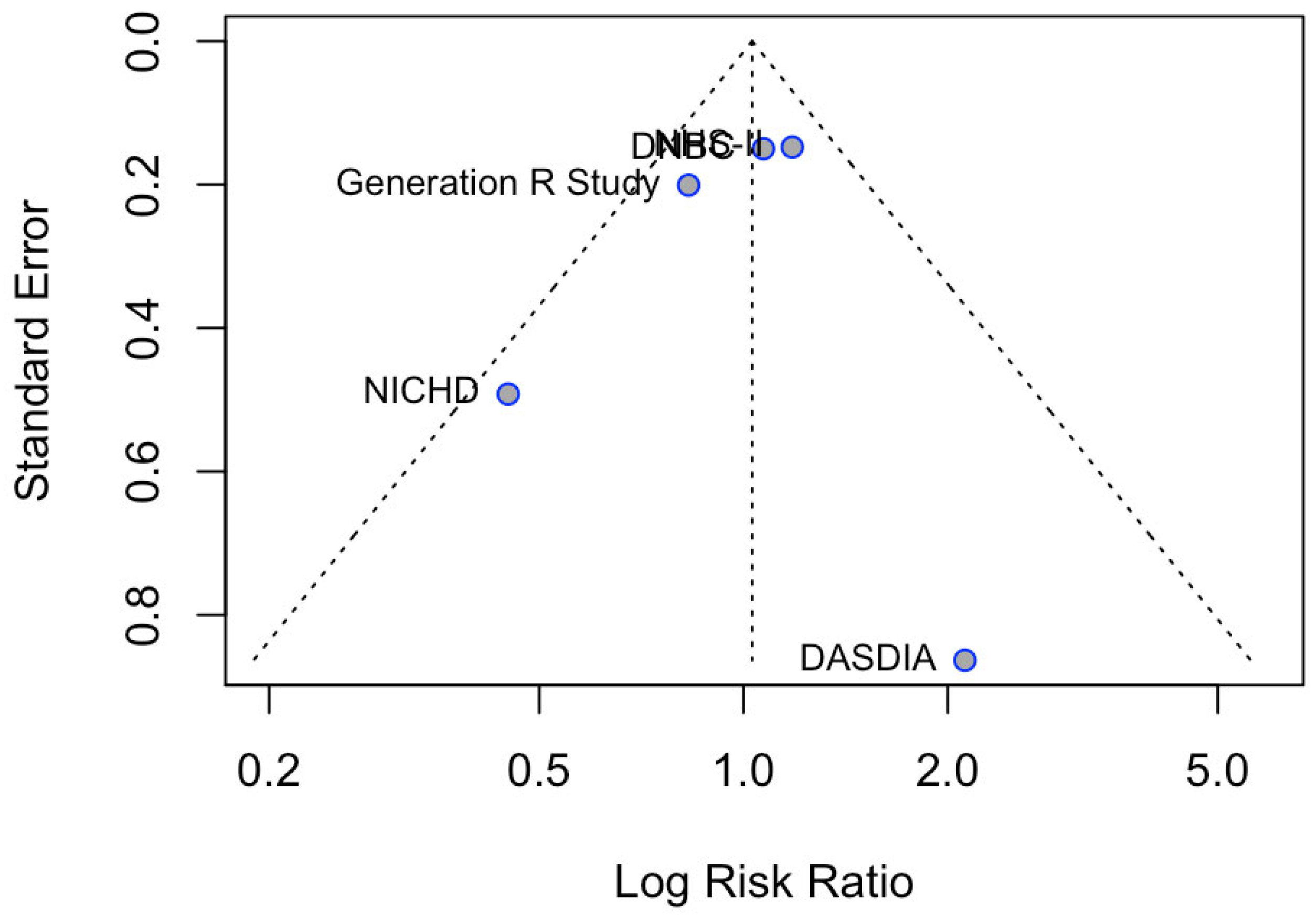

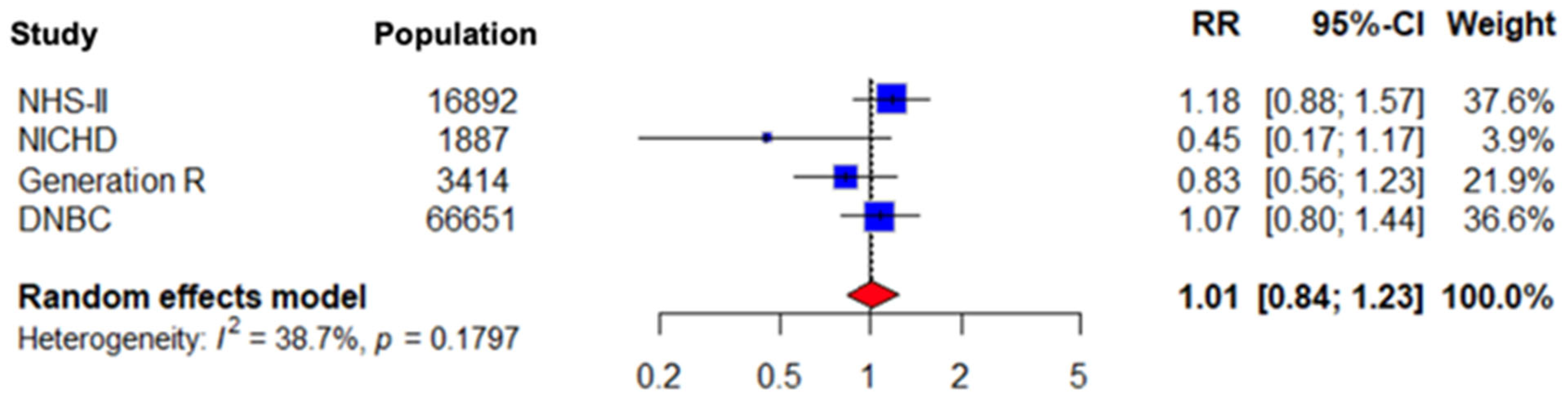

3.6. Subgroup Analysis Results for Preeclampsia

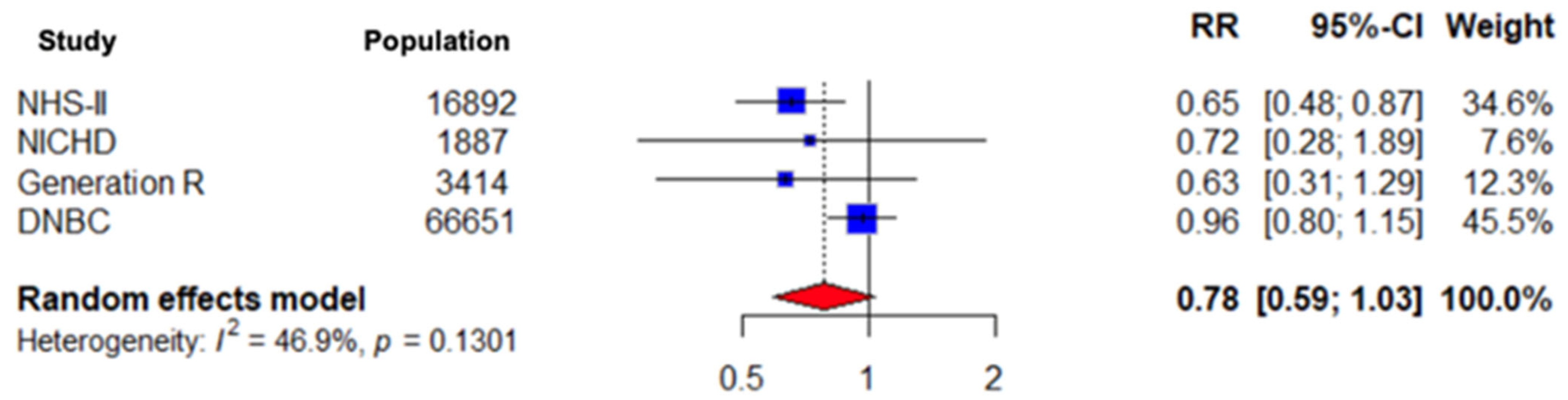

3.7. Sensitivity Analysis Results for Observational Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Writing Committee Members; Jones, D.W.; Ferdinand, K.C.; Taler, S.J.; Johnson, H.M.; Shimbo, D.; Abdalla, M.; Altieri, M.M.; Bansal, N.; Bello, N.A.; et al. 2025 AHA/ACC/AANP/AAPA/ABC/ACCP/ACPM/AGS/AMA/ASPC/NMA/PCNA/SGIM Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 152, e114–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyselaers, W. Preeclampsia Is a Syndrome with a Cascade of Pathophysiologic Events. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garovic, V.D.; Dechend, R.; Karumanchi, S.A.; McMurtry Baird, S.; Easterling, T.; Magee, L.A.; Rana, S.; Vermunt, J.V.; August, P. Hypertension in Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Blood Pressure Goals, and Pharmacotherapy. Hypertension 2022, 79, e21–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, J.; Darmochwał-Kolarz, D. A Review of the Diagnosis, Risk Factors, and Role of Angiogenetic Factors in Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Med. Sci. Monit. 2025, 31, e945628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.O.; Gao, W.; Hibbard, J.U. Obstetrical and Perinatal Outcomes among Women with Gestational Hypertension, Mild Preeclampsia, and Mild Chronic Hypertension. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 260.e1–260.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Lin, L.; Gao, D.; Wu, M.; Yang, S.; Cao, X.; et al. Folic Acid Supplement Use and Increased Risk of Gestational Hypertension. Hypertension 2020, 76, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Z.; Ye, S.; Lin, D.; Fan, D.; Guo, X.; Liu, Z. Association between Iron Status, Preeclampsia and Gestational Hypertension: A Bidirectional Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 86, 127528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, H.H.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Huh, S.Y.; Kleinman, K.; Litonjua, A.A.; Oken, E.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Gillman, M.W. Vitamin D Status and Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 399–403.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, E.A.; Magkos, F.; Zingenberg, H.; Svare, J.; Astrup, A.; Geiker, N.R.W. A High Protein Low Glycemic Index Diet Has No Adverse Effect on Blood Pressure in Pregnant Women with Overweight or Obesity: A Secondary Data Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1289395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsdottir, A.S.; Skuladottir, G.V.; Thorsdottir, I.; Hauksson, A.; Thorgeirsdottir, H.; Steingrimsdottir, L. Relationship between High Consumption of Marine Fatty Acids in Early Pregnancy and Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. BJOG 2006, 113, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksmańska, W.; Bobiński, R.; Ulman-Włodarz, I.; Pielesz, A. The Differences in the Consumption of Proteins, Fats and Carbohydrates in the Diet of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Arterial Hypertension or Arterial Hypertension and Hypothyroidism. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenaker, D.A.; Soedamah-Muthu, S.S.; Callaway, L.K.; Mishra, G.D. Prepregnancy Dietary Patterns and Risk of Developing Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy: Results from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health11. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. DASH Eating Plan. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/DASH-eating-plan (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Azadbakht, L.; Surkan, P.J. The DASH Diet and Insulin Resistance in Gestational Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, M.J.; Kovell, L.C.; Turkson-Ocran, R.-A.; Mukamal, K.J.; Liu, X.; Appel, L.J.; Miller, E.R.; Sacks, F.M.; Christenson, R.H.; Rebuck, H.; et al. Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet on Change in Cardiac Biomarkers Over Time: Results From the DASH-Sodium Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e026684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asemi, Z.; Samimi, M.; Tabassi, Z.; Sabihi, S.S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Investigating the Effect of DASH Diet on Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Gestational Diabetes. Nutrition 2013, 29, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gan, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Santos, H.O.; Okunade, K.; Kathirgamathamby, V. Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) on Pregnancy/Neonatal Outcomes and Maternal Glycemic Control: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 54, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, N.H.M. PRISMA2020. Available online: https://www.eshackathon.org/software/PRISMA2020.html (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, J.R.; Norvell, D.C.; Chapman, J.R. Fixed-Effect vs Random-Effects Models for Meta-Analysis: 3 Points to Consider. Global Spine J. 2022, 12, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, G. Meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis. Version 2025, 8. R package, 1–0. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/index.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Arvizu, M.; Stuart, J.J.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Gaskins, A.J.; Rosner, B.; Chavarro, J.E. Prepregnancy Adherence to Dietary Recommendations for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Relation to Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Grewal, J.; Hinkle, S.N.; Yisahak, S.F.; Grobman, W.A.; Newman, R.B.; Skupski, D.W.; Chien, E.K.; Wing, D.A.; Grantz, K.L.; et al. Healthy Dietary Patterns and Common Pregnancy Complications: A Prospective and Longitudinal Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertsema, C.J.; Mensink-Bout, S.M.; Duijts, L.; Mulders, A.G.M.G.J.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Gaillard, R. Associations of DASH Diet in Early Pregnancy with Blood Pressure Patterns, Placental Hemodynamics, and Gestational Hypertensive Disorders. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e017503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvizu, M.; Bjerregaard, A.A.; Madsen, M.T.B.; Granström, C.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Olsen, S.F.; Gaskins, A.J.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Rosner, B.A.; Chavarro, J.E.; et al. Sodium Intake during Pregnancy, but Not Other Diet Recommendations Aimed at Preventing Cardiovascular Disease, Is Positively Related to Risk of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J. Nutr. 2019, 150, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, K.; Rosado, E.L.; da Fonseca, A.C.P.; Belfort, G.P.; da Silva, L.B.G.; Ribeiro-Alves, M.; Zembrzuski, V.M.; Campos, M., Jr.; Zajdenverg, L.; Drehmer, M.; et al. A Pilot Study of Dietetic, Phenotypic, and Genotypic Features Influencing Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy in Women with Pregestational Diabetes Mellitus. Life 2023, 13, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, M.; Shariati, M.; Nikbakht, R.; Masihi, S. Investigating Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) on Pregnancy Outcomes of Pregnant Women with Chronic and Gestational Hypertension. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Cancer Res. 2023, 8, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Li, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, H.; Gao, B.; Xu, B.; Li, X.; Chen, W. The Efficacy of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet with Respect to Improving Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with Hypertensive Disorders. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 32, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesco, K.; Leo, M.; Gillman, M.; King, J.; McEvoy, C.; Karanjaa, N.; Perrin, N.; Eckhardt, C.; Smith, K.S.; Stevens, V. LB 2: Impact of a Weight Management Intervention on Pregnancy Outcomes among Obese Women: The Healthy Moms Trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 208, S352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulay, A.P.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E.; Perng, W. Associations of the Dietary Approaches To Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet with Pregnancy Complications in Project Viva. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanpour, V.; Khoshhali, M.; Goodarzi-Khoigani, M.; Kelishadi, R. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nutritional Interventions to Prevent of Gestational Hypertension or/and Preeclampsia among Healthy Pregnant Women. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2023, 28, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Authors | Study Quality | NOS Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS-II (Nurses’ Health Study II) | Arvizu et al. | Very good | 9/9 |

| NICHD Fetal Growth Studies—Singletons | Li et al. | Very good | 9/9 |

| Generation R Study | Wiertsema et al. | Very good | 9/9 |

| DNBC (Danish National Birth Cohort) | Arvizu et al. | Very good | 9/9 |

| Study | Authors | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|

| DASDIA | Santos et al. | Unclear risk of bias |

| First Author | Population, N | Study Design | Main Findings | Follow-Up | Confounding Factors | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvizu et al. | 11,535 | Prospective cohort study | Reduced risk of GH and preeclampsia in highest DASH quintiles | 1991–2009 | Age, BMI, physical activity, energy intake, smoking, prior pregnancy | DASH diet associated with lower risk of preeclampsia, no significant effect on GH. Highest risk in low DASH adherence |

| Arvizu et al. | 66,651 | Prospective cohort study | No significant difference in GH risk across DASH categories | Jan 1996- Oct 2002 | Age, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking, diabetes status, etc. | No significant association between DASH and GH or preeclampsia risk |

| Li et al. | 1887 | Prospective cohort study | No significant association with GH; reduced preeclampsia risk with high DASH adherence | 2009–2013 | Maternal age, race, education, marital status, pre-pregnancy BMI, physical activity, sleep, energy intake | DASH diet reduces risk of preeclampsia, but not GH |

| Wiertsema et al. | 3414 | Prospective cohort study | Lower systolic and diastolic BP in Q4 DASH score; no significant difference in HDP | 2002–2006 | Maternal age, BMI, smoking, alcohol, education, folic acid, energy intake | DASH diet may benefit BP during pregnancy but has no significant effect on hypertensive disorders |

| Santos et al. | 70 | RCT | No significant differences in development of HDP of pregnancy between groups. | 2016–2020 | Diabetes type (1 vs. 2), Diabetes onset time, Pre-pregnancy BMI, History of preeclampsia, Socioeconomic status and ethnicity | DASH diet had no significant effect on preventing HDP in pregnant women with diabetes. Some genetic and phenotypic factors were linked to increased HDP risk |

| First Author | Country | Gestational Week (Weeks) | Age (Years) | Low DASH (Age) | High DASH (Age) | High DASH, N | High DASH, N | GH Low DASH % | GH High DASH, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvizu et al. | Denmark | 25 | 30 ± 4 | 30 ± 4 | 31 ± 4 | 14.685 | 14.586 | 1% | 0.9% |

| Arvizu et al. | USA | >20 | 34.6 | 34.1 (3.9) | 35.1 (3.8) | 2135 | 2333 | 3.3% | 3.9% |

| Li et al. | USA | 16–22 | 28.1 | 25.5 ± 5.43 | 30.4 ± 4.84 | 1682 | 404 | 6.2% | 5.8% |

| Santos et al. | Brazil | <28 | 32 (25.7–36.0) | 31 (25.0–35.0) | 34 (28–37) | 31 | 34 | 4.9% | 10.3% |

| Wiertsema et al. | Netherlands | 8–13 | 31.4 (4.4) | 29.7 (5.0) | 32.5 (3.8) | 860 | 920 | 6.3% | 5.2% |

| First Author | Study | DASH Assessment Instrument | Scoring System | Exposure Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arvizu et al. | DNBC | FFQ | Sum of 1–5 points per component (fruits/fruit juices, vegetables, low-fat dairy, red/processed meats, SSBs, sodium, whole grains, nuts/legumes) based on intake quintiles within the study population | The closest FFQ preceding each pregnancy |

| Arvizu et al. | NHS-II (Nurses’ Health Study II) | FFQ (at median 25 wks) | Sum of 1–5 points per component (fruits/fruit juices, vegetables, low-fat dairy, red/processed meats, SSBs, sodium, whole grains, nuts/legumes) based on intake quintiles within the study population | Previous 4 weeks from FFQ |

| Li et al. | NICHD Fetal Growth Studies—Singletons | FFQ (8–13 wks), ASA24 (16–22 and 24–29 wks) | Sum of 1–5 points per component (fruits/fruit juices, vegetables, low-fat dairy, red/processed meats, SSBs, sodium, whole grains, nuts/legumes) based on intake quintiles within the study population | 8–13 wks, 16–22, 24–29 wks. |

| Santos et al. | DASDIA | 24 h dietary recalls and adherence evaluation tool (4 items: quantity, variety, meals, gestational weight gain) | Score 0–4 points per visit based on adherence to DASH components (high adherence ≥2, low-to-moderate <2) | From inclusion (approx. <28 wks gestation) until delivery |

| Wiertsema et al. | Generation R | FFQ (at median 13 wks) | Sum of 1–5 points per component (fruits/fruit juices, vegetables, low-fat dairy, red/processed meats, SSBs, sodium, whole grains, nuts/legumes) based on intake quintiles within the study population | 3 mo prior to enrollment (periconception and early pregnancy) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alatsis, A.; Xixi, N.A.; Sokou, R.; Volaki, P.; Paliatsiou, S.; Iliodromiti, Z.; Iacovidou, N.; Boutsikou, T. The Effect of the DASH Diet on the Development of Gestational Hypertension in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2026, 18, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020268

Alatsis A, Xixi NA, Sokou R, Volaki P, Paliatsiou S, Iliodromiti Z, Iacovidou N, Boutsikou T. The Effect of the DASH Diet on the Development of Gestational Hypertension in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020268

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlatsis, Anastasios, Nikoleta Aikaterini Xixi, Rozeta Sokou, Paraskevi Volaki, Styliani Paliatsiou, Zoi Iliodromiti, Nicoletta Iacovidou, and Theodora Boutsikou. 2026. "The Effect of the DASH Diet on the Development of Gestational Hypertension in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020268

APA StyleAlatsis, A., Xixi, N. A., Sokou, R., Volaki, P., Paliatsiou, S., Iliodromiti, Z., Iacovidou, N., & Boutsikou, T. (2026). The Effect of the DASH Diet on the Development of Gestational Hypertension in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 18(2), 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020268