Pioneering Insights into the Complexities of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension: Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Dietary Bioactive Compound Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Regulatory Mechanism of CNS in the SSH

2.1. CNS Autonomic Circuits and SSH

2.2. Factors Leading to Increased PVN Neuronal Activity and Sympathetic Outflow in Patients with SSH

2.2.1. Ion Channels: SK Channels Expressed in the PVN and Excitability of Autonomic PVN Neurons

2.2.2. Intercellular Communication: Brain-Derived EVs Mediate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Activation in the PVN

2.2.3. Inflammation/Oxidative Stress: Multiple Pathways Amplify PVN Regional Imbalance and Neurotransmitter Dysregulation

2.2.4. Signal Molecule Regulation: Salt Load-Dependent Protective Effects of CO and H2S

2.2.5. Glial Cell Regulation: Gαi2 Protein Inhibits PVN Microglial Activation to Alleviate SSH

2.2.6. Neuropeptide Regulation: Orexin System-Mediated Sympathetic Activation and ABP Regulation

3. The Role of Subcellular Stress in SSH

3.1. Mitochondrial Stress

3.2. ER Stress

4. The Pathogenic Mechanism of a High-Salt Diet Driving an Increase in ABP

4.1. Pathological Reactions of the Peripheral System to a High-Salt Diet

4.2. A Salt-Rich Diet Can Lead to an Increase in Sodium Ion Concentration in CSF

4.3. Immune Dysfunction Caused by High Sodium Intake

4.4. Deterioration of Endothelial Function Caused by High-Sodium Diet

4.5. Sex Dimorphism in SSH

5. Epigenetic Modifications and SSH: Emerging Targets in Immunometabolism and Signaling Pathways

5.1. Histone Methylation: A Regulator of Renal Sodium Metabolism in SSH

5.2. Genetic Variation-Epigenetic Modification Interaction Mediates Salt Sensitivity

5.3. Summary: Epigenetic Modifications as Core Mechanisms and Targets for SSH Intervention

6. Bioactive Compounds and SSH

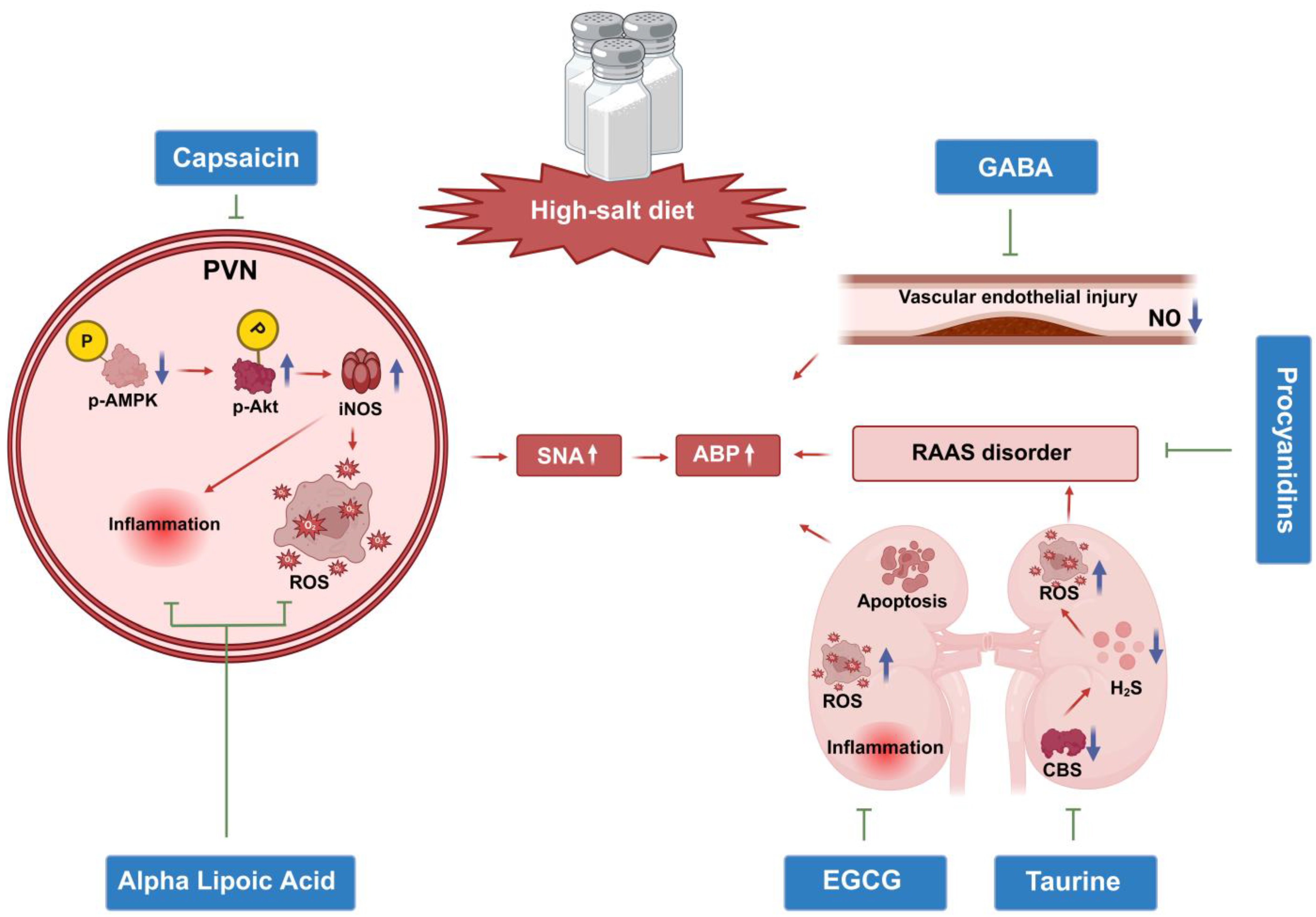

6.1. Central Regulatory Mechanisms of Natural Bioactive Components: Novel Targets and Translational Potential for SSH Intervention

6.1.1. Capsaicin: Central AMPK/Akt/iNOS Pathway Regulation and Bidirectional Effects of TRPV1 Receptors

6.1.2. Alpha Lipoic Acid (ALA): Central Oxidative Stress Inhibition and Regulation of the RAAS/Inflammatory Cytokine Network

6.2. GABA: Neurotransmitter Balance Restoration and Peripheral Vascular Homeostasis Regulation

6.3. Peripheral Target Organ Protection: Focus on Local Pathological Reversal of RAAS and Oxidative Stress

6.3.1. Procyanidins: RAAS Inhibition and Vascular Function Protection

6.3.2. Tea Active Components: Subcellular Stress Inhibition and Renal Function Protection

6.4. Taurine: CBS/H2S Pathway Restoration and Multi-Target Synergistic Effects

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, P.; Ekmekcioglu, C. Impact of Salt Intake on the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, D.L.; Dasinger, J.H.; Abais-Battad, J.M. Gut-Immune-Kidney Axis: Influence of Dietary Protein in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2397–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; He, J.; Li, C.; Lu, X.; He, W.J.; Cao, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.C.; Bazzano, L.A.; Li, J.X.; et al. Metabolomics study of blood pressure salt-sensitivity and hypertension. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdev, S.; Prabhakaran, V.; Sampson, C.A. Elevated 22Na uptake in aortae of Dahl salt-sensitive rats with high salt diet. Artery 1990, 17, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chachoo, J.; Mushtaq, N.; Jan, S.; Majid, S.; Mohammad, I. Clinical variables accompanying salt-sensitive essential hypertension in ethnic Kashmiri population. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasdev, S.; Gill, V.D.; Parai, S.; Gadag, V. Effect of moderately high dietary salt and lipoic acid on blood pressure in Wistar-Kyoto rats. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2007, 12, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, S.D. Altered Neuronal Discharge in the Organum Vasculosum of the Lamina Terminalis Contributes to Dahl Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Hypertension 2023, 80, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhara, M.; Neikirk, K.; Marshall, A.; Hinton, A., Jr.; Kirabo, A. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Hypertension and Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Afsar, R.E. Mitochondrial Damage and Hypertension: Another Dark Side of Sodium Excess. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perla, S.; Garcia-Milan, R.; Mopidevi, B.; Jain, S.; Kumar, A. Effect of Dietary Salt excess on DNA Methylation and Transcriptional Regulation of human Angiotensinogen (hAGT) Gene Expression. Am. J. Hypertens. 2025, hpaf150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tini, G.; Tocci, G.; Battistoni, A.; Sarocchi, M.; Pietrantoni, C.; Russo, D.; Musumeci, B.; Savoia, C.; Volpe, M.; Spallarossa, P. Role of Arterial Hypertension and Hypertension-Mediated Organ Damage in Cardiotoxicity of Anticancer Therapies. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2023, 20, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duus, C.L.; Nielsen, S.F.; Hornstrup, B.G.; Mose, F.H.; Bech, J.N. Self-Performed Dietary Sodium Reduction and Blood Pressure in Patients with Essential Hypertension: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e034632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, S.A.; Salehzadeh, M.; Ghavami, H.; Asl, R.G.; Vatani, K.K. Impact of lifestyle interventions on reducing dietary sodium intake and blood pressure in patients with hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Turk. Kardiyol. Dern. Ars. 2021, 49, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Ji, X. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) attenuates salt-induced hypertension and renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, P.; Ubom, R.; Madueke, P.; Okorie, P.; Nwachukwu, D. Anti-Hypertensive Effects of Anthocyanins from Hibiscus sabdarifa Calyx on the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldoslestrone System in Wistar Rats. Niger. J. Physiol. Sci. 2022, 37, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Duan, Y.; Cheng, M. Clinical Diagnostic Value of Serum GABA, NE, ET-1, and VEGF in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease with Pulmonary Hypertension. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideishi, M.; Miura, S.; Sakai, T.; Sasaguri, M.; Misumi, Y.; Arakawa, K. Taurine amplifies renal kallikrein and prevents salt-induced hypertension in Dahl rats. J. Hypertens. 1994, 12, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Huang, Y.; Lv, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, G.; Tao, Y.; Bu, D.; Wang, G.; Du, J.; et al. Endogenous Taurine Downregulation Is Required for Renal Injury in Salt-Sensitive Hypertensive Rats via CBS/H(2)S Inhibition. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5530907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenstedt, E.F.E.; Engberink, R.H.O.; Rorije, N.M.G.; van den Born, B.H.; Claessen, N.; Aten, J.; Vogt, L. Salt-sensitive blood pressure rise in type 1 diabetes patients is accompanied by disturbed skin macrophage influx and lymphatic dilation-a proof-of-concept study. Transl. Res. 2020, 217, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, R.K.; Stock, J.M.; Romberger, N.T.; Wenner, M.M.; Chai, S.C.; Farquhar, W.B. The impact of dietary sodium and fructose on renal sodium handling and blood pressure in healthy adults. Physiol. Rep. 2025, 13, e70284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary, S.; Boder, P.; Padmanabhan, S.; McBride, M.W.; Graham, D.; Delles, C.; Dominiczak, A.F. Role of Uromodulin in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2419–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawarazaki, W.; Fujita, T. Role of Rho in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutchler, S.M.; Kirabo, A.; Kleyman, T.R. Epithelial Sodium Channel and Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Hypertension 2021, 77, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, R.B.; Nishi, E.E.; Crajoinas, R.O.; Milanez, M.I.O.; Girardi, A.C.C.; Campos, R.R.; Bergamaschi, C.T. Relative Contribution of Blood Pressure and Renal Sympathetic Nerve Activity to Proximal Tubular Sodium Reabsorption via NHE3 Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng Earley, Y.; Pan, S.; Verma, H.; Zheng, H.; Plata, A.A.; Zubcevic, J.; Leenen, F.H.H. Central nervous system mechanisms of salt-sensitive hypertension. Physiol. Rev. 2025, 105, 1989–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, C.D.; Gholami, K.; Lam, S.K.; Hoe, S.Z. A preliminary study of the effect of a high-salt diet on transcriptome dynamics in rat hypothalamic forebrain and brainstem cardiovascular control centers. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzęda, E.; Ziarniak, K.; Sliwowska, J.H. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus—The concertmaster of autonomic control. Focus on blood pressure regulation. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2023, 83, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.L.; Tjen, A.L.S.C.; Nguyen, A.T.; Fu, L.W.; Su, H.F.; Gong, Y.D.; Malik, S. Adenosine A(2A) receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla participate in blood pressure decrease with electroacupuncture in hypertensive rats. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1275952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, N.M.; Fekete, E.M.; Muskus, P.C.; Brozoski, D.T.; Lu, K.T.; Wackman, K.K.; Gomez, J.; Fang, S.; Reho, J.J.; Grobe, C.C.; et al. Genetic Ablation of Prorenin Receptor in the Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla Influences Blood Pressure and Hydromineral Balance in Deoxycorticosterone-Salt Hypertension. Function 2023, 4, zqad043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, V.A.; Medeiros, I.A.; Ribeiro, T.P.; França-Silva, M.S.; Botelho-Ono, M.S.; Guimarães, D.D. Angiotensin-II-induced reactive oxygen species along the SFO-PVN-RVLM pathway: Implications in neurogenic hypertension. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2011, 44, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottrell, G.T.; Ferguson, A.V. Sensory circumventricular organs: Central roles in integrated autonomic regulation. Regul. Pept. 2004, 117, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collister, J.P.; Nahey, D.B.; Hartson, R.; Wiedmeyer, C.E.; Banek, C.T.; Osborn, J.W. Lesion of the OVLT markedly attenuates chronic DOCA-salt hypertension in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 315, R568–R575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, T.S.; Takakura, A.C.; Colombari, E.; Menani, J.V. Antihypertensive effects of central ablations in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R1797–R1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.V.; Latchford, K.J.; Samson, W.K. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus—A potential target for integrative treatment of autonomic dysfunction. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2008, 12, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Katsurada, K.; Nandi, S.; Li, Y.; Patel, K.P. A Critical Role for the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Hypothalamus in the Regulation of the Volume Reflex in Normal and Various Cardiovascular Disease States. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2022, 24, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Wang, J.X.; Chen, J.L.; Dai, M.; Wang, Y.M.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.H.; Zhu, G.Q.; Chen, A.D. GLP-1 in the Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus Promotes Sympathetic Activation and Hypertension. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e2032232024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.J.; Wang, R.; Chen, Q.H. Autonomic Regulation of the Cardiovascular System: Diseases, Treatments, and Novel Approaches. Neurosci. Bull. 2019, 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauar, M.R.; Pestana-Oliveira, N.; Collister, J.P.; Vulchanova, L.; Evans, L.C.; Osborn, J.W. The organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis contributes to neurohumoral mechanisms of renal vascular hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2025, 328, R161–R171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Toney, G.M. AT(1)-receptor blockade in the hypothalamic PVN reduces central hyperosmolality-induced renal sympathoexcitation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001, 281, R1844–R1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapp, A.D.; Wang, R.; Cheng, Z.J.; Shan, Z.; Chen, Q.H. Long-Term High Salt Intake Involves Reduced SK Currents and Increased Excitability of PVN Neurons with Projections to the Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla in Rats. Neural Plast. 2017, 2017, 7282834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, J.W.; Fink, G.D.; Sved, A.F.; Toney, G.M.; Raizada, M.K. Circulating angiotensin II and dietary salt: Converging signals for neurogenic hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2007, 9, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourque, C.W. Central mechanisms of osmosensation and systemic osmoregulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, A.V.; Washburn, D.L.; Latchford, K.J. Hormonal and neurotransmitter roles for angiotensin in the regulation of central autonomic function. Exp. Biol. Med. 2001, 226, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Deng, S.; Chen, X.; Ruan, J.; Wang, H.; Zhan, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Z. TMEM63B functions as a mammalian hyperosmolar sensor for thirst. Neuron 2025, 113, 1430–1445.e1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Nishida, Y.; Zhou, M.S.; Murakami, H.; Okada, K.; Morita, H.; Hosomi, H.; Kosaka, H. Sinoaortic denervation produces sodium retention in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1998, 69, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.A.; Gui, L.; Huber, M.J.; Chapp, A.D.; Zhu, J.; LaGrange, L.P.; Shan, Z.; Chen, Q.H. Sympathoexcitation in ANG II-salt hypertension involves reduced SK channel function in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H1547–H1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Andrade, M.A.; Calderon, A.S.; Toney, G.M. Hypertension induced by angiotensin II and a high salt diet involves reduced SK current and increased excitability of RVLM projecting PVN neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.J.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, E.; Zhu, F.; Larson, R.A.; Yan, J.; Li, N.; Chen, Q.H.; Shan, Z. Increased activity of the orexin system in the paraventricular nucleus contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 313, H1075–H1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigalke, J.A.; Gao, H.; Chen, Q.H.; Shan, Z. Activation of Orexin 1 Receptors in the Paraventricular Nucleus Contributes to the Development of Deoxycorticosterone Acetate-Salt Hypertension Through Regulation of Vasopressin. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 641331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Jiang, E.; Gao, H.; Bigalke, J.; Chen, B.; Yu, C.; Chen, Q.; Shan, Z. Activation of Orexin System Stimulates CaMKII Expression. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 698185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.D.; Liang, Y.F.; Qi, J.; Kang, K.B.; Yu, X.J.; Gao, H.L.; Liu, K.L.; Chen, Y.M.; Shi, X.L.; Xin, G.R.; et al. Carbon Monoxide Attenuates High Salt-Induced Hypertension While Reducing Pro-inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress in the Paraventricular Nucleus. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2019, 19, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.F.; Zhang, D.D.; Yu, X.J.; Gao, H.L.; Liu, K.L.; Qi, J.; Li, H.B.; Yi, Q.Y.; Chen, W.S.; Cui, W.; et al. Hydrogen sulfide in paraventricular nucleus attenuates blood pressure by regulating oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines in high salt-induced hypertension. Toxicol. Lett. 2017, 270, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, J.D.; Chaudhary, P.; Frame, A.A.; Puleo, F.; Nist, K.M.; Abkin, E.A.; Moore, T.L.; George, J.C.; Wainford, R.D. Inhibition of microglial activation in rats attenuates paraventricular nucleus inflammation in Gαi2 protein-dependent, salt-sensitive hypertension. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 1892–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Kang, Y.M.; Li, X.G.; Su, Q.; Li, H.B.; Liu, K.L.; Fu, L.Y.; Saahene, R.O.; Li, Y.; Tan, H.; et al. Central blockade of NLRP3 reduces blood pressure via regulating inflammation microenvironment and neurohormonal excitation in salt-induced prehypertensive rats. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Yu, X.J.; Li, X.G.; Pang, D.Z.; Su, Q.; Saahene, R.O.; Li, H.B.; Mao, X.Y.; Liu, K.L.; Fu, L.Y.; et al. Blockade of TLR4 Within the Paraventricular Nucleus Attenuates Blood Pressure by Regulating ROS and Inflammatory Cytokines in Prehypertensive Rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Liu, J.J.; Cui, W.; Shi, X.L.; Guo, J.; Li, H.B.; Huo, C.J.; Miao, Y.W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Q.; et al. Alpha lipoic acid supplementation attenuates reactive oxygen species in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and sympathoexcitation in high salt-induced hypertension. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 241, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yu, X.J.; Shi, X.L.; Gao, H.L.; Yi, Q.Y.; Tan, H.; Fan, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.A.; Cui, W.; et al. NF-κB Blockade in Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus Inhibits High-Salt-Induced Hypertension Through NLRP3 and Caspase-1. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2016, 16, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Bigalke, J.; Jiang, E.; Fan, Y.; Chen, B.; Chen, Q.H.; Shan, Z. TNFα Triggers an Augmented Inflammatory Response in Brain Neurons from Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats Compared with Normal Sprague Dawley Rats. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 42, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.H.; Morita, H.; Nishida, Y.; Hosomi, H. Effects of a high-salt diet on tissue noradrenaline concentrations in Dahl salt-resistant and -sensitive rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1995, 22, S209–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.A.; Chapp, A.D.; Gui, L.; Huber, M.J.; Cheng, Z.J.; Shan, Z.; Chen, Q.H. High Salt Intake Augments Excitability of PVN Neurons in Rats: Role of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Store. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Gingerich, L.; Chen, Q.H.; Bi, L.; Shan, Z. Induction of Neuroinflammation and Brain Oxidative Stress by Brain-Derived Extracellular Vesicles from Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domondon, M.; Polina, I.; Nikiforova, A.B.; Sultanova, R.F.; Kruger, C.; Vasileva, V.Y.; Fomin, M.V.; Beeson, G.C.; Nieminen, A.L.; Smythe, N.; et al. Renal Glomerular Mitochondria Function in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Chen, G.; Tong, L.; Ye, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W.; Zhang, S.; et al. PDZD8-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria associations regulate sympathetic drive and blood pressure through the intervention of neuronal mitochondrial homeostasis in stress-induced hypertension. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 183, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xia, L.; Ye, X.; Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Feng, W.; Du, D.; Chen, Y. Ultrathin Niobium Carbide MXenzyme for Remedying Hypertension by Antioxidative and Neuroprotective Actions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202303539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisberger, S.; Bartolomaeus, H.; Neubert, P.; Willebrand, R.; Zasada, C.; Bartolomaeus, T.; McParland, V.; Swinnen, D.; Geuzens, A.; Maifeld, A.; et al. Salt Transiently Inhibits Mitochondrial Energetics in Mononuclear Phagocytes. Circulation 2021, 144, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajina, I.; Stupin, A.; Šola, M.; Mihalj, M. Oxidative Stress Induced by High Salt Diet-Possible Implications for Development and Clinical Manifestation of Cutaneous Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction in Psoriasis vulgaris. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Xie, X.H.; Chen, C.H.; Peng, X.; Zhang, P.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.T. Molecular Regulation Mechanisms and Interactions Between Reactive Oxygen Species and Mitophagy. DNA Cell Biol. 2019, 38, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, M.; Sharifi, R.; Heydari, N.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Ezzati-Mobasser, S.; Zarrinnahad, H. Circulating TRB3 and GRP78 levels in type 2 diabetes patients: Crosstalk between glucose homeostasis and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2022, 45, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.M.; Regolisti, G.; Peyronel, F.; Fiaccadori, E. Recent insights into sodium and potassium handling by the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: A review of the relevant physiology. J. Nephrol. 2020, 33, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, S.; Mu, S.; Kawarazaki, H.; Muraoka, K.; Ishizawa, K.; Yoshida, S.; Kawarazaki, W.; Takeuchi, M.; Ayuzawa, N.; Miyoshi, J.; et al. Rac1 GTPase in rodent kidneys is essential for salt-sensitive hypertension via a mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3233–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.S.; Van Vliet, B.N.; Leenen, F.H. Increases in CSF [Na+] precede the increases in blood pressure in Dahl S rats and SHR on a high-salt diet. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 287, H1160–H1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, Y.; Takata, Y.; Takishita, S.; Tomita, Y.; Tsuchihashi, T.; Fujishima, M. Cerebrospinal fluid sodium and enhanced hypertension in salt-loaded spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 1992, 10, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, T.; Hagiwara, Y. Enhanced central hypertonic saline-induced activation of angiotensin II-sensitive neurons in the anterior hypothalamic area of spontaneously hypertensive and Dahl S rats. Brain Res. Bull. 2006, 68, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsman, B.J.; Simmonds, S.S.; Browning, K.N.; Stocker, S.D. Organum Vasculosum of the Lamina Terminalis Detects NaCl to Elevate Sympathetic Nerve Activity and Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2017, 69, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, M.; Hirooka, Y.; Matsukawa, R.; Ito, K.; Sunagawa, K. Mineralocorticoid receptors/epithelial Na+ channels in the choroid plexus are involved in hypertensive mechanisms in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res. 2013, 36, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Wu, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Tian, M.; Huang, L.; Li, Z.; et al. Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, K.; Stumpf, N.E.; Schwab, S.; Eichler, M.; Neubert, P.; Rauh, M.; Adamowski, M.; Babyak, O.; Hinze, D.; Sivalingam, S.; et al. A high-salt diet compromises antibacterial neutrophil responses through hormonal perturbation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, H.; Geisberger, S.; Luft, F.C.; Wilck, N.; Stegbauer, J.; Wiig, H.; Dechend, R.; Jantsch, J.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Kempa, S.; et al. Sodium as an Important Regulator of Immunometabolism. Hypertension 2024, 81, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.L.; Kitz, A.; Wu, C.; Lowther, D.E.; Rodriguez, D.M.; Vudattu, N.; Deng, S.; Herold, K.C.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; et al. Sodium chloride inhibits the suppressive function of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 4212–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri Barbaro, N.; Van Beusecum, J.; Xiao, L.; do Carmo, L.; Pitzer, A.; Loperena, R.; Foss, J.D.; Elijovich, F.; Laffer, C.L.; Montaniel, K.R.; et al. Sodium activates human monocytes via the NADPH oxidase and isolevuglandin formation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilck, N.; Matus, M.G.; Kearney, S.M.; Olesen, S.W.; Forslund, K.; Bartolomaeus, H.; Haase, S.; Mähler, A.; Balogh, A.; Markó, L.; et al. Salt-responsive gut commensal modulates TH17 axis and disease. Nature 2017, 551, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Crowley, S.D. Role of T-cell activation in salt-sensitive hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 316, H1345–H1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patik, J.C.; Lennon, S.L.; Farquhar, W.B.; Edwards, D.G. Mechanisms of Dietary Sodium-Induced Impairments in Endothelial Function and Potential Countermeasures. Nutrients 2021, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kawakami-Mori, F.; Kang, L.; Ayuzawa, N.; Ogura, S.; Koid, S.S.; Reheman, L.; Yeerbolati, A.; Liu, B.; Yatomi, Y.; et al. Low-dose L-NAME induces salt sensitivity associated with sustained increased blood volume and sodium-chloride cotransporter activity in rodents. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 1242–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.L.; Harwood, D.; Bender, L.; Shrestha, L.; Brands, M.W.; Morwitzer, M.J.; Kennard, S.; Antonova, G.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Lack of Suppression of Aldosterone Production Leads to Salt-Sensitive Hypertension in Female but Not Male Balb/C Mice. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barris, C.T.; Faulkner, J.L.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure in Women. Hypertension 2023, 80, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abais-Battad, J.M.; Dasinger, J.H.; Lund, H.; Burns-Ray, E.C.; Walton, S.D.; Baldwin, K.E.; Fehrenbach, D.J.; Cherian-Shaw, M.; Mattson, D.L. Sex-Dependency of T Cell-Induced Salt-Sensitive Hypertension and Kidney Damage. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1511–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutchler, A.L.; Haynes, A.P.; Saleem, M.; Jamison, S.; Khan, M.M.; Ertuglu, L.; Kirabo, A. Epigenetic Regulation of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2025, 136, 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wu, X.; Long, L.; Li, S.; Huang, M.; Li, M.; Feng, P.; Levi, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; et al. TGR5 attenuates DOCA-salt hypertension through regulating histone H3K4 methylation of ENaC in the kidney. Metabolism 2025, 165, 156133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.Y.; Yang, Y.; Jia, X.T.; Jiang, D.L.; Fu, L.Y.; Tian, H.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Liu, K.L.; Kang, Y.M.; et al. Capsaicin pretreatment attenuates salt-sensitive hypertension by alleviating AMPK/Akt/Nrf2 pathway in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1416522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, D.H. Activation of TRPV1 Prevents Salt-Induced Kidney Damage and Hypertension After Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2018, 43, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Sun, F.; Li, P.; Xia, W.; Zhou, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Taurine Supplementation Lowers Blood Pressure and Improves Vascular Function in Prehypertension: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Hypertension 2016, 67, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, M.; Oh, S.; Lee, H.S.; Choi, J.; Lee, B.J.; Park, J.H.; Park, C.H.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Gamma-aminobutyric acid-salt attenuated high cholesterol/high salt diet induced hypertension in mice. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2021, 25, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, M.; Toyoshi, T.; Sano, A.; Izumi, T.; Fujii, T.; Konishi, C.; Inai, S.; Matsukura, C.; Fukuda, N.; Ezura, H.; et al. Antihypertensive effect of a gamma-aminobutyric acid rich tomato cultivar ‘DG03-9’ in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oketch-Rabah, H.A.; Madden, E.F.; Roe, A.L.; Betz, J.M. United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Safety Review of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szallasi, A. The Vanilloid (Capsaicin) Receptor TRPV1 in Blood Pressure Regulation: A Novel Therapeutic Target in Hypertension? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Privitera, R.; Donatien, P.; Fadavi, H.; Tesfaye, S.; Bravis, V.; Misra, V.P. Reversing painful and non-painful diabetic neuropathy with the capsaicin 8% patch: Clinical evidence for pain relief and restoration of function via nerve fiber regeneration. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 998904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superti, F.; Russo, R. Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Biological Mechanisms and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogeswara, I.B.A.; Maneerat, S.; Haltrich, D. Glutamate Decarboxylase from Lactic Acid Bacteria-A Key Enzyme in GABA Synthesis. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, D.H.; Vo, T.S. An Updated Review on Pharmaceutical Properties of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid. Molecules 2019, 24, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.X.; Wang, S.; Wei, L.; Cui, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.H. Proanthocyanidins: Components, Pharmacokinetics and Biomedical Properties. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 813–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Cheng, J.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, H.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Li, W.; Bao, W.; Rong, S. The effect of grape seed procyanidins extract on cognitive function in elderly people with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesana, A.; Rodrigues, E.; Noreña, C.P.Z. Composition analysis of carotenoids and phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity from hibiscus calyces (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) by HPLC-DAD-MS/MS. Phytochem. Anal. 2019, 30, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Arellano, A.; Flores-Romero, S.; Chávez-Soto, M.A.; Tortoriello, J. Effectiveness and tolerability of a standardized extract from Hibiscus sabdariffa in patients with mild to moderate hypertension: A controlled and randomized clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2004, 11, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.Y.; Duan, S.Y.; Liu, F.C.; Yao, Q.K.; Tu, S.; Xu, Y.; Pan, C.W. Blood Pressure Is Associated with Tea Consumption: A Cross-sectional Study in a Rural, Elderly Population of Jiangsu China. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, R.; Huang, J.; Cai, Q.; Yang, C.S.; Wan, X.; Xie, Z. Effects and Mechanisms of Tea Regulating Blood Pressure: Evidences and Promises. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Cheang, W.; Yuen Ngai, C.; Yen Tam, Y.; Yu Tian, X.; Tak Wong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wai Lau, C.; Chen, Z.Y.; Bian, Z.X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Black tea protects against hypertension-associated endothelial dysfunction through alleviation of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Bu, P. The effect of black tea supplementation on blood pressure: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Influencing Factors | Origin | Pathophysiological Indicators | Molecular Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK | PVN | SNA ↑ ABP ↑ Neuronal firing ↑ | SK channels ↓ | [41,47,48] |

| Orexin system | PVN | ABP ↑ AVP ↑ | OX1R ↑ CaMKII ↑ | [49,50,51] |

| CO | PVN | SNA ↓; ABP ↓ NE ↓ | COX2, IL-1β, IL-6, NOX2, and NOX4 ↓ HO-1 and Cu/Zn-SOD ↑ | [52] |

| H2S | PVN | SNA ↓ABP ↓ HR ↓ NE ↓ | NOX2, NOX4 and IL-1β ↓ H2S, CBS, IL-10 and Cu/Zn SOD ↑ | [53] |

| Gαi2 protein | PVN Microglial cells | ABP ↑ Plasma noradrenaline ↑ Plasma renin activity ↑ Urinary angiotensinogen ↑ | TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 ↓ IL-10 ↑ | [54] |

| NLRP3 | PVN | ABP ↑ Plasma noradrenaline ↑ CD4+, CD8+ T cell, and CD8+ microglia ↑ | CCL2, CXCR3, and VCAM-1 ↑ GAD67 ↓ TH ↑ GABA↓ | [55] |

| TLR4 | PVN | SNA ↑ ABP ↑ | Myd88, NF-κB, PICs, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, NOX2 and NOX4 ↑ SOD level ↓ TH ↑ GAD67 ↓ | [56] |

| ROS | PVN | SNA ↑ ABP ↑ | ACE, gp91(phox), gp47(phox) (subunits of NAD(P)H oxidase), AT1R, IL-1β, IL-6 ↑ IL-10 and Cu/Zn-SOD ↓ | [57] |

| NF-κB | PVN | ABP ↑ NE ↑ EPI ↑ | p-IKKβ, NF-κB p65 activity, Fra-LI activity (an indicator of chronic neuronal activation), NOX-4 (subunits of NAD(P)H oxidase), NLRP3, and IL-1β ↑ IL-10 ↓ | [58] |

| TNF-α | PVN and cultured brain neurons from neonatal SD rats | ABP ↑ | IL-1β, IL6, CCL5, CCL12, iNOS, and transcription factor NF-kB ↑ | [59] |

| Chemical Compound | Source | Human Dosage/ Animal Dosage | Target Organ | Pathophysiological Indicators | Main Mechanism of Action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | Chili | ---/ DSS rats: PVN infusion | PVN | Thickness of ventricular walls and shrunken heart chambers, ↓ ANP and BNP ↓ | NOX2, iNOS, NOX4, and p-IKKβ ↓ Nrf2 and HO-1 ↑ p-PI3K and p-AKT ↓ p-AMPK ↑ | [91,92] |

| ALA | Spinach, broccoli, and animal livers | ---/ Via gastric perfusion (60 mg/kg for 9 weeks) | PVN | SNA ↑ ABP ↑ | ACE, gp91(phox), gp47(phox) (subunits of NAD(P)H oxidase), AT1R, IL-1β, IL-6 ↑ IL-10 and Cu/Zn-SOD ↓ | [57] |

| Taurine | Meat, seafood, dairy, and other foods | ---/ DSS rats: 2%~3% added to drinking water (4~6 weeks, equivalent to 10~15 g/d in humans, supraphysiological dose) | Renal tissue | ABP ↓ CDO1 and CSAD ↑ | SOD1, SOD2 ↑ Renin, gp91phox, p22phox, and p47phox ↓ | [18,19,93] |

| GABA | Fermented foods and specific plants | 0.3–2 g/d (dietary equivalent dose)/Hypertensive mice: GABA salt (based on dietary salt intake ratio) | Vascular function | ABP ↓ EC dysfunction ↓ | GABAB receptor and eNOS phosphorylation ↑ E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and EC ↓ Endothelin-1 levels ↓ | [17,94,95,96] |

| Procyanidins | Mainly derived from plant tissues such as grape seeds and blueberries | 0–2.5 mg/kg body weight/day (acceptable daily intake, ADI)/high-salt-induced hypertensive rats: 50, 100, 200 mg/kg | Serum RAAS | ABP and heart rate ↓ | Serum ACE and plasma aldosterone ↓ | [16] |

| EGCG | Tea | No clear SSH-specific dose | Renal tissue | ABP ↓ 24 h urine protein levels, creatinine clearance, renal fibrosis ↓ | Malondialdehyde levels, the number of infiltrated macrophages and T cells ↓ | [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Xu, B.; Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Miodonski, G.; Shan, Z.; Du, D.; Chen, Q.-H. Pioneering Insights into the Complexities of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension: Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Dietary Bioactive Compound Interventions. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243961

Wang R, Xu B, Liu X, Guo Q, Miodonski G, Shan Z, Du D, Chen Q-H. Pioneering Insights into the Complexities of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension: Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Dietary Bioactive Compound Interventions. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243961

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Renjun, Bo Xu, Xiping Liu, Qi Guo, Gregory Miodonski, Zhiying Shan, Dongshu Du, and Qing-Hui Chen. 2025. "Pioneering Insights into the Complexities of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension: Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Dietary Bioactive Compound Interventions" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243961

APA StyleWang, R., Xu, B., Liu, X., Guo, Q., Miodonski, G., Shan, Z., Du, D., & Chen, Q.-H. (2025). Pioneering Insights into the Complexities of Salt-Sensitive Hypertension: Central Nervous System Mechanisms and Dietary Bioactive Compound Interventions. Nutrients, 17(24), 3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243961