Understanding Australian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Healthy and Sustainable Diets, and Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Focus Group Data Collection

2.3.2. Online Survey Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Focus Group Data Analysis

2.4.2. Online Survey Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Focus Group Results—Perceptions and Consumption of Healthy and Sustainable Diets

3.2.1. Capability

3.2.2. Opportunity

3.2.3. Motivation

3.3. Focus Groups Discussion Results—Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses

3.3.1. Capability

3.3.2. Opportunity

“If you look at the foods we eat in Australia, they sort of, like, stem from cultures. Like, we’ll have a lot of pasta, the Italian and, you know, things like that. But where they eat a lot of lentils and things like that, that’s not really like a widespread meal option, or thought about. Like, I don’t eat a lot of them. I have eaten them before, but I reckon if you go outside and ask 20 people if they’ve eaten lentils before, at least 18 will say no.”(FG2)

“Because you like, eat [a prepared pulse dish from the school tuckshop] and touch it, like, but you don’t know how to make it. Like, when you’re out of school, how are you going to eat it?”(FG1)

“if we have vegetable patches or, like, even if you just get agriculture, it’s like, it’s offered at most schools where, you know, you learn how to grow different types of vegetables, different types of fruits. And then obviously you can incorporate that into your home ec’ classes, then you don’t have to go buy it. You’ve got that natural stuff there. And then you can teach people how to, you know, cook it as well, so then you kind of full circle. You’re teaching people how to grow it, teaching people how to cook it, and then people are eating.”(FG2)

“And I know like you can buy chickpeas and things like that, like canned, but like they’re often, like, I don’t know, like the Aldi I go to, they’re in the very back corner like sort of hidden away from the rest of the vegetables.”(FG2)

3.3.3. Motivation

“For example, like, mushrooms-noone likes mushrooms. Except for [XX]. So… my mum used to, like, hide them, not hide them, but, like, put in a dish where you can’t really taste them. You can taste, like, other flavours that taste way better… like sauce or something.”(FG1)

“So I think it’s about just knowing your intention, saying “Alright, I like them. I’m gonna go cook them.” So I think if you introduce [pulse dishes in home economics] more to the youth and maybe they’ll cook it and eat it. And then, yeah, start eating it more, yeah.”(FG2)

“It also depends on age, like, if you’re an adult and you’re living independently by yourself, you go to that time to prepare yourself so it would be more beneficial to know how to prepare them. But as teenagers we kind of rely on what our parents cook for us and make for us every day. So, like, and for the young people would be just convenience rather than learning how to prepare them.”(FG2)

3.4. Pulse Survey Results

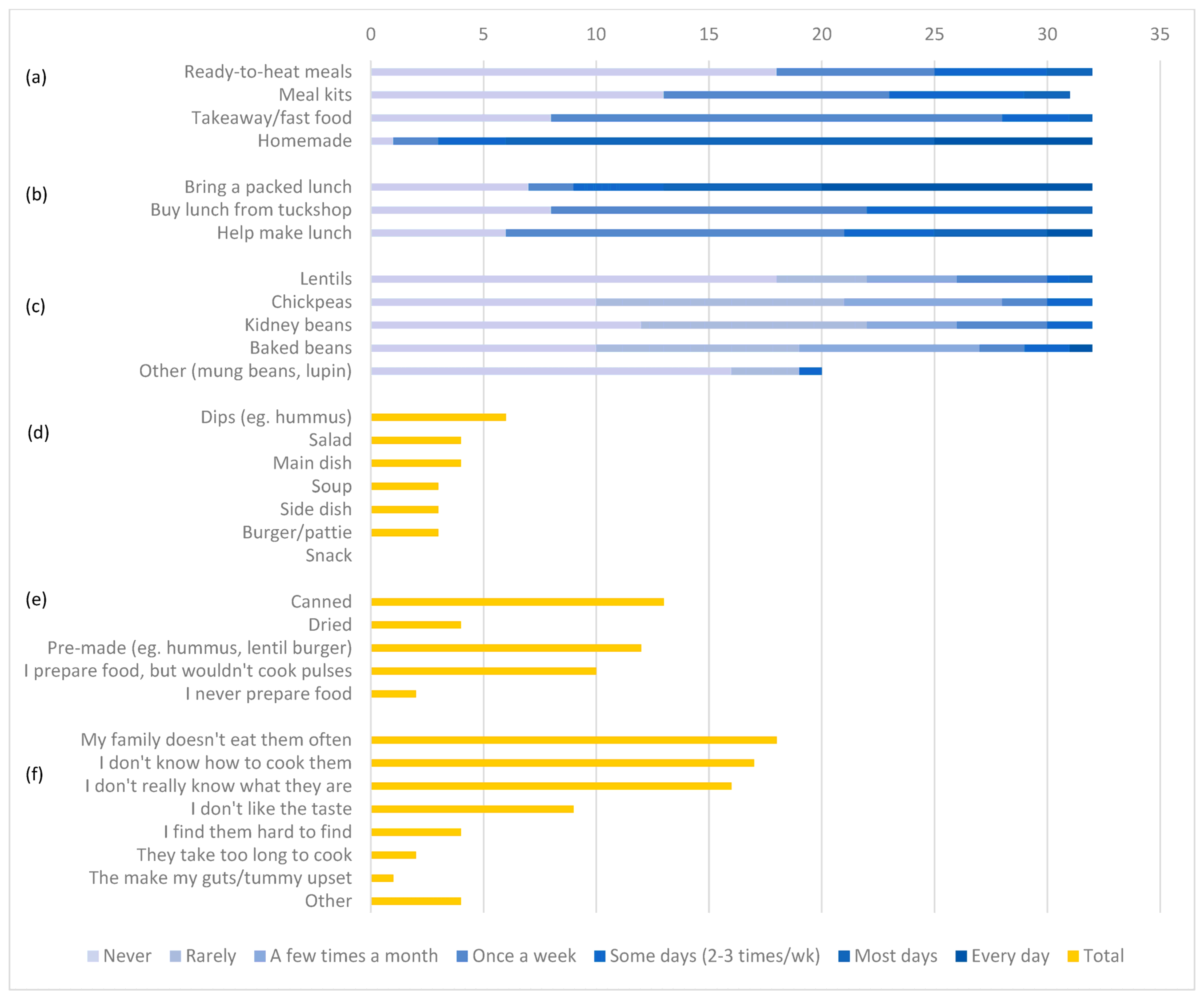

3.4.1. Food Preparation of Adolescents

3.4.2. Adolescents’ Pulse Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCW | Behaviour Change Wheel |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for Behaviour |

| FG | Focus Group |

References

- Neufeld, L.M.; Andrade, E.B.; Suleiman, A.B.; Barker, M.; Beal, T.; Blum, L.S.; Demmler, K.M.; Dogra, S.; Hardy-Johnson, P.; Lahiri, A.; et al. Food choice in transition: Adolescent autonomy, agency, and the food environment. Lancet 2022, 399, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization; World Health Organisation. Sustainable Healthy Diets—Guiding Principles; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, P.; Nyman, M.; Murphy, L.; Oyebode, O. Building a Food System That Works for Everyone; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- James-Martin, G.; Baird, D.L.; Hendrie, G.A.; Bogard, J.; Anastasiou, K.; Brooker, P.G.; Wiggins, B.; Williams, G.; Herrero, M.; Lawrence, M.; et al. Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: A global review. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e977–e986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Nutrition Across the Life Stages; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Leme, A.C.B.; Hou, S.; Fisberg, R.M.; Fisberg, M.; Haines, J. Adherence to Food-Based Dietary Guidelines: A Systemic Review of High-Income and Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Food and Nutrients. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/food-and-nutrition/food-and-nutrients/latest-release (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Steenson, S.; Buttriss, J.L. Healthier and more sustainable diets: What changes are needed in high-income countries? Nutr. Bull. 2021, 46, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margier, M.; Georgé, S.; Hafnaoui, N.; Remond, D.; Nowicki, M.; Du Chaffaut, L.; Amiot, M.-J.; Reboul, E. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Content of Legumes: Characterization of Pulses Frequently Consumed in France and Effect of the Cooking Method. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedoussac, L.; Journet, E.-P.; Hauggaard-Nielsen, H.; Naudin, C.; Corre-Hellou, G.; Jensen, E.S.; Prieur, L.; Justes, E. Ecological principles underlying the increase of productivity achieved by cereal-grain legume intercrops in organic farming. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.P.; Reckling, M.; Chadwick, D.; Rees, R.M.; Saget, S.; Williams, M.; Styles, D. Legume-Modified Rotations Deliver Nutrition With Lower Environmental Impact. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 656005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeld, D.; Hughes, J.; Grafenauer, S. The changing landscape of legume products available in australian supermarkets. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-09/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Rockström, J.; Thilsted, S.H.; Willett, W.C.; Gordon, L.J.; Herrero, M.; Hicks, C.C.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Rao, N.; Springmann, M.; Wright, E.C.; et al. The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. Lancet 2025, 406, 1625–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, T.; Russo, C.; Takata, Y.; Bobe, G. Legume Consumption Patterns in US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2014 and Beans, Lentils, Peas (BLP) 2017 Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and health benefits of pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions, 1st ed.; Silverback Publishing: Sutton, UK, 2014; pp. 1003–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Wadi, N.M.; Cheikh, K.; Keung, Y.W.; Green, R. Investigating intervention components and their effectiveness in promoting environmentally sustainable diets: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e410–e422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, J.M.; Simpson, E.E.A.; Timlin, D. Using the COM-B model to identify barriers and facilitators towards adoption of a diet associated with cognitive function (MIND diet). Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, T.J.; Pang, B.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Capability, opportunity, and motivation: An across contexts empirical examination of the COM-B model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuinn, S.; Belton, S.; Staines, A.; Sweeney, M.R. Co-design of a school-based physical activity intervention for adolescent females in a disadvantaged community: Insights from the Girls Active Project (GAP). BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford University Press. Perception. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/perception (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanham, A.R.; van der Pols, J.C. Toward Sustainable Diets—Interventions and Perceptions Among Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 83, e694–e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, M.; Vasconcelos, M.; Pinto, E. Pulse Consumption among Portuguese Adults: Potential Drivers and Barriers towards a Sustainable Diet. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, N.; Curtain, F.; Beck, E.; Grafenauer, S. Consumer Understanding and Culinary Use of Legumes in Australia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winham, D.M.; Davitt, E.D.; Heer, M.M.; Shelley, M.C. Pulse knowledge, attitudes, practices, and cooking experience of midwestern us university students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bouwman, E.P.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H. A systematic review on consumer acceptance of alternative proteins: Pulses, algae, insects, plant-based meat alternatives, and cultured meat. Appetite 2021, 159, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczebyło, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Laskowski, W. Towards more sustainable diets—Attitudes, opportunities and barriers to fostering pulse consumption in polish cities. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Waterfield, J. Focus group methodology: Some ethical challenges. Qual. Quant. 2019, 53, 3003–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, S.; Schumm, J.S.; Sinagub, J. Focus Group Interviews in Education and Psychology; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, A.; Seward, K.; Finch, M.; Fielding, A.; Stacey, F.; Jones, J.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.L. Barriers and Enablers to Implementation of Dietary Guidelines in Early Childhood Education Centers in Australia: Application of the Theoretical Domains Framework. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 229–237.e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics XM; Qualtrics: Provo, UT, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Volume 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardropper, C.B.; Dayer, A.A.; Goebel, M.S.; Martin, V.Y. Conducting conservation social science surveys online. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higher Level Panel of Experts. Nutrition and Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Government. Australian Curriculum: Health and Physical Education. Available online: https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/p-10/aciq/version-8/learning-areas/health-and-physical-education/australian-curriculum (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. What is the status of food literacy in Australian high schools? Perceptions of home economics teachers. Appetite 2017, 108, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, N.; Begley, A. Adolescent food literacy programmes: A review of the literature. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 71, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, G.C.B.S.d.; Azevedo, K.P.M.d.; Garcia, D.; Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Mata, Á.N.d.S.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; Santos, R.P.d.; Trindade, D.D.B.d.B.; Moreno, I.M.; Guillén Martínez, D.; et al. Effect of School-Based Food and Nutrition Education Interventions on the Food Consumption of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P.E.; Elinder, L.S.; Lindroos, A.K.; Parlesak, A. Designing Nutritionally Adequate and Climate-Friendly Diets for Omnivorous, Pescatarian, Vegetarian and Vegan Adolescents in Sweden Using Linear Optimization. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensson, L.F.J.; Hunter, D.; Schneider, S.; Tartanac, F. Public food procurement as a game changer for food system transformation. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e495–e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronto, R.; Carins, J.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ views on high school food environments. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 32, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; French, S. Individual and Environmental Influences on Adolescent Eating Behaviors. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, S40–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.; Deforche, B.; Van Kerckhove, A.; Michels, N.; Geuens, M.; Van Lippevelde, W. Intervention strategies to promote healthy and sustainable food choices among parents with lower and higher socioeconomic status. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capper, T.E.; Brennan, S.F.; Woodside, J.V.; McKinley, M.C. What makes interventions aimed at improving dietary behaviours successful in the secondary school environment? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 2448–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersch, D.; Perdue, L.; Ambroz, T.; Boucher, J.L. The Impact of Cooking Classes on Food-Related Preferences, Attitudes, and Behaviors of School-Aged Children: A Systematic Review of the Evidence, 2003–2014. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.J.; Drummond, M.J.; Ward, P.R. Food literacy programmes in secondary schools: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2891–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, G.B.; Haileslassie, H.A.; Shand, P.; Lin, Y.; Lieffers, J.R.L.; Henry, C. Pulse-Based Nutrition Education Intervention Among High School Students to Enhance Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices: Pilot for a Formative Survey Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e45908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.D.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K. Nutrition promotion approaches preferred by Australian adolescents attending schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grains & Legumes Nutrition Council. Consumption & Attitudes Study Results: 2017. Available online: https://www.glnc.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/GLNC-Consumption-Study-Summary-5.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2026).

- Rawal, V.; Navarro, D.K. (Eds.) The Global Economy of Pulses; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.; Hillen, C.; Garden Robinson, J. Composition, Nutritional Value, and Health Benefits of Pulses. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidåker, P.; Karlsson Potter, H.; Carlsson, G.; Röös, E. Towards sustainable consumption of legumes: How origin, processing and transport affect the environmental impact of pulses. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, K.; Zhang, X.; Thomsen, M.; Rinnan, Å.; Bredie, W.L.P. The versatility of pulses: Are consumption and consumer perception in different European countries related to the actual climate impact of different pulse types? Future Foods 2022, 6, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, E.D.F.; Gomes, A.M.; Gil, A.M.; Vasconcelos, M.W. The Transition towards Sustainable Diets Should Encourage Pulse Consumption in Children’s Diets: Insights for Policies in Food Systems. JOCD 2021, 5, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozer, N.; Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Poutanen, K. Traditional and New Food Uses of Pulses. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behaviour | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption of healthy foods/limited consumption of unhealthy foods (n = 133) | |||||

| Healthy dietary consumption pattern (n = 14) | |||||

| Sustainable behaviours (n = 8) | |||||

| Capability (n = 1) | Opportunity (n = 45) | Motivation (n = 59) | |||

| Psychological | Physical | Social | Physical | Reflective | Automatic |

| Lack of knowledge (n = 1) | Cultural norms (n = 2) | School tuckshop (n = 6) | Value of healthy eating (n = 17) | Stress (n = 3) | |

| Global food system (n = 4) | Value of sustainable diets (n = 6) | Ambivalence (n = 3) | |||

| Food production and soil impacts (n = 7) | Value of the environment (n = 5) | Disappointment (n = 1) | |||

| Transport and packaging (n = 3) | Benefit for sports performance (n = 5) | ||||

| Food accessibility (n = 1) | Energy balance of unhealthy foods (n = 2) | ||||

| Food environment (n = 1) | Health and nourishment (n = 4) | ||||

| Waste (n = 17) | Competing priorities (n = 4) | ||||

| Time (n = 1) | Consumer role and responsibility (n = 2) | ||||

| Cost (n = 1) | Future generations (n = 1) | ||||

| Alternative protein sources (n = 2) | Convenience (n = 1) | ||||

| Suggested interventions | |||||

| Education in school curriculum regarding what constitutes a health and sustainable diet, and the role of consumers | |||||

| Restructuring of food environment to improve access and appeal of healthy and sustainable foods, including attractive labelling and advertising | |||||

| Behaviour | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption of pulses (n = 224) | |||||

| Capability (n = 93) | Opportunity (n = 79) | Motivation (n = 55) | |||

| Psychological | Physical | Social | Physical | Reflective | Automatic |

| Lack of knowledge (n = 20) | Cooking and food preparation skills (n = 38) | Parents’ influence (n = 3) | Pulses in main dishes (n = 22) | Convenience (n = 8) | Familiarity (n = 22) |

| Knowledge (n = 17) | Practice (n = 1) | Peers’ influence (n = 2) | School tuckshop (n = 12) | Desirability (n = 3) | Taste (n = 13) |

| Media as an information source (n = 9) | Teachers’ influence (n = 2) | Home economics classes (n = 8) | Intention to consume pulses (n = 3) | Stress (n = 2) | |

| Social networks as an information source (n = 7) | Cultural norms (n = 1) | Pulses as a meal addition (n = 6) | Lack of desirability of foods (n = 1) | Appealing foods (n = 1) | |

| Food labelling as an information source (n = 1) | Pulse consumers (n = 1) | Time (n = 6) | Role in food preparation (n = 1) | Lack of satiety (n = 1) | |

| Pulses in the food environment and accessibility (n = 3) | |||||

| Cost (n = 3) | |||||

| Pulses in ultra-processed foods (n = 2) | |||||

| School curriculum (n = 2) | |||||

| Pulse production (n = 1) | |||||

| Pulse transport and packaging (n = 1) | |||||

| Pulses as snacks (n = 1) | |||||

| Suggested interventions | |||||

| Education regarding the benefits and ways of consuming pulses | |||||

| Restructuring of food environments to increase the access and appeal of pulse foods, including attractive labelling and advertising | |||||

| Training adolescents to equip them with the skills to prepare tasty and/or familiar pulse foods for themselves | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lanham, A.R.; Tulloch, A.I.T.; Bogard, J.R.; van der Pols, J.C. Understanding Australian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Healthy and Sustainable Diets, and Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses. Nutrients 2026, 18, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020265

Lanham AR, Tulloch AIT, Bogard JR, van der Pols JC. Understanding Australian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Healthy and Sustainable Diets, and Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020265

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanham, Adeline R., Ayesha I. T. Tulloch, Jessica R. Bogard, and Jolieke C. van der Pols. 2026. "Understanding Australian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Healthy and Sustainable Diets, and Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020265

APA StyleLanham, A. R., Tulloch, A. I. T., Bogard, J. R., & van der Pols, J. C. (2026). Understanding Australian Adolescents’ Perceptions of Healthy and Sustainable Diets, and Perceptions and Consumption of Pulses. Nutrients, 18(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020265