A Novel Food-Derived Particle Enhances Sweet and Salty Taste Responses in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Compounds

2.2. Animals

2.3. Taste Behavior Assessment in Mice

2.4. Gustatory Nerve Recording in Mice

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

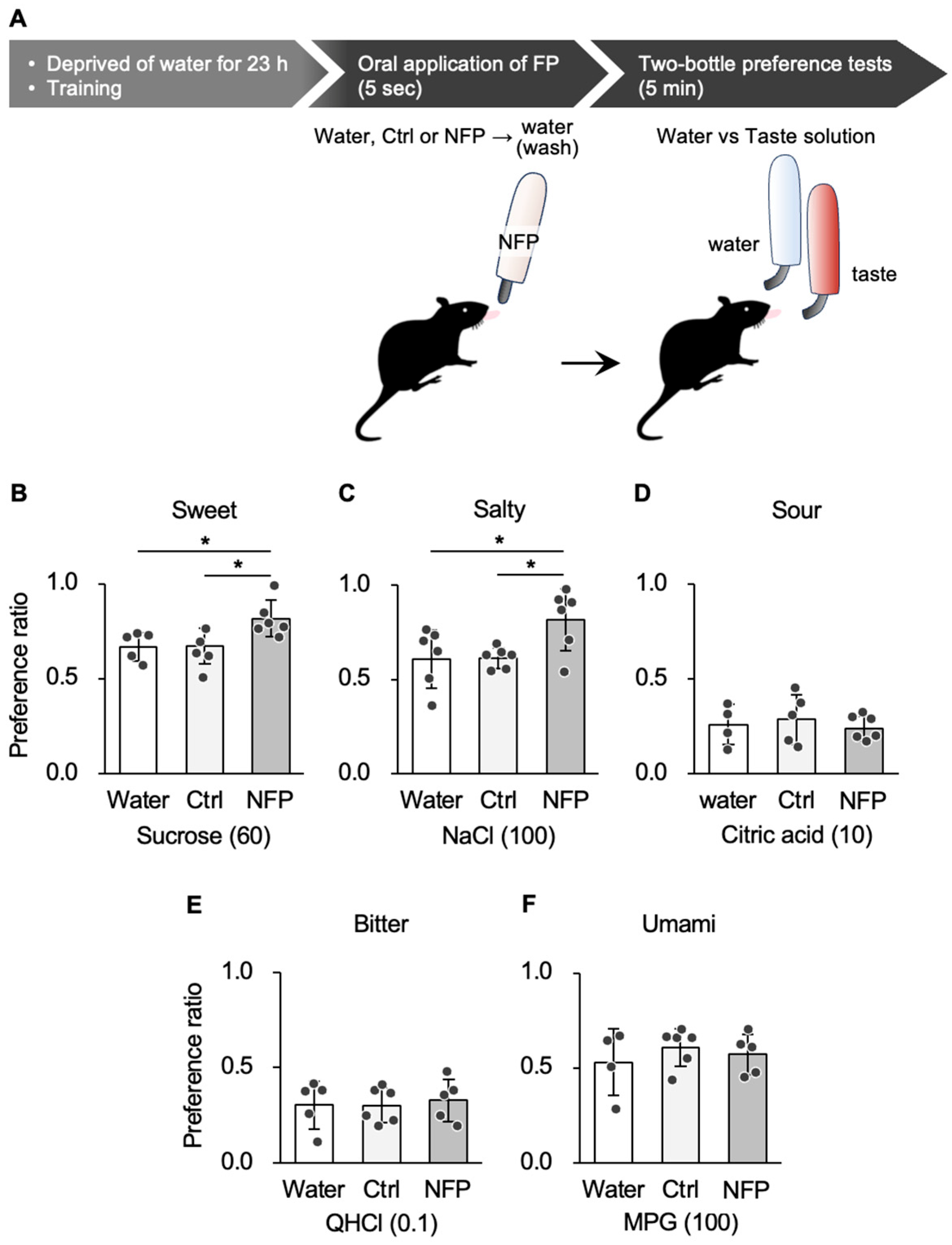

3.1. Effect of NFPs on Taste Preference Behavior in Response to Taste Stimuli

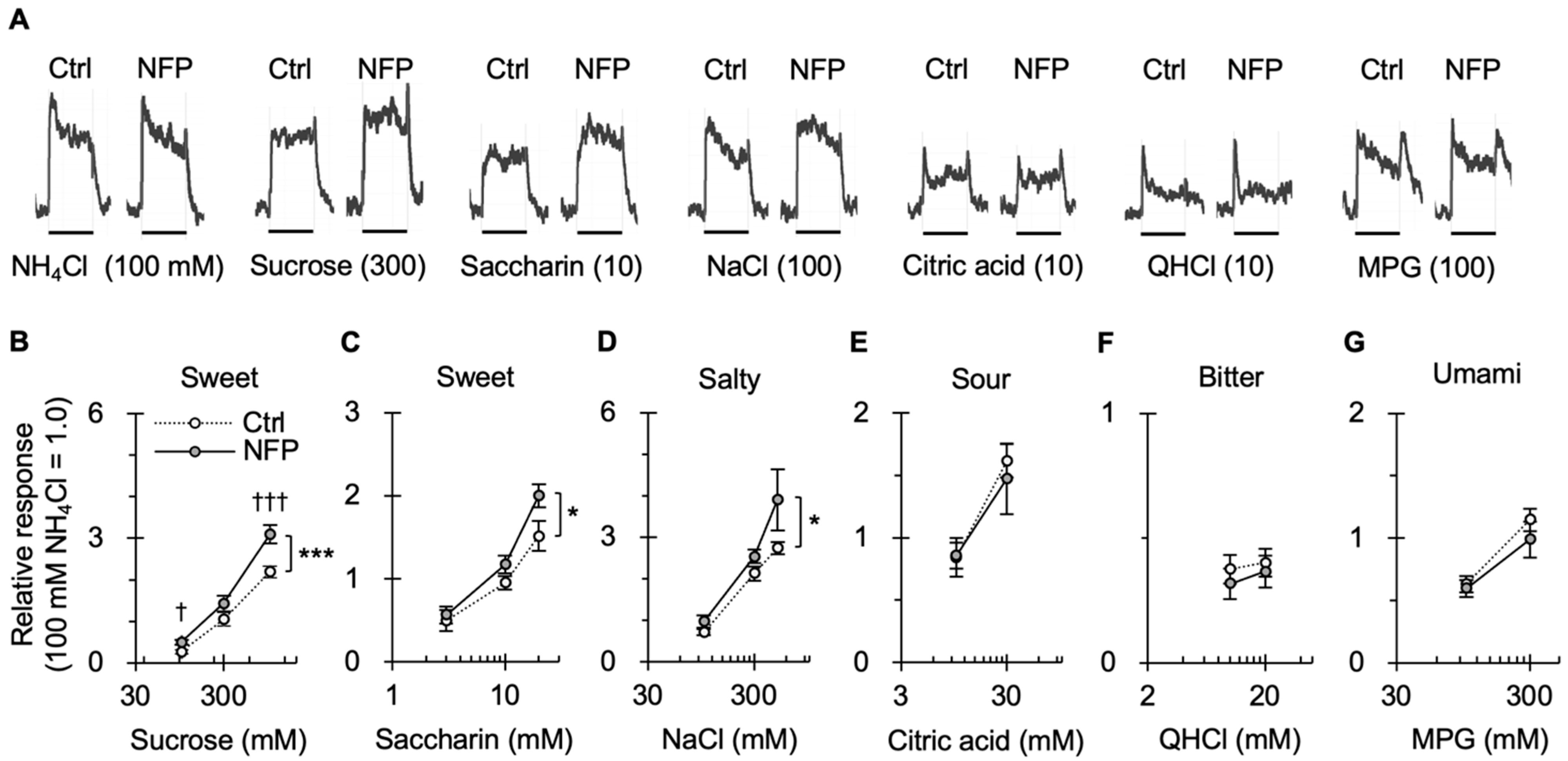

3.2. Effect of NFPs on Gustatory Nerve Responses to Taste Stimuli

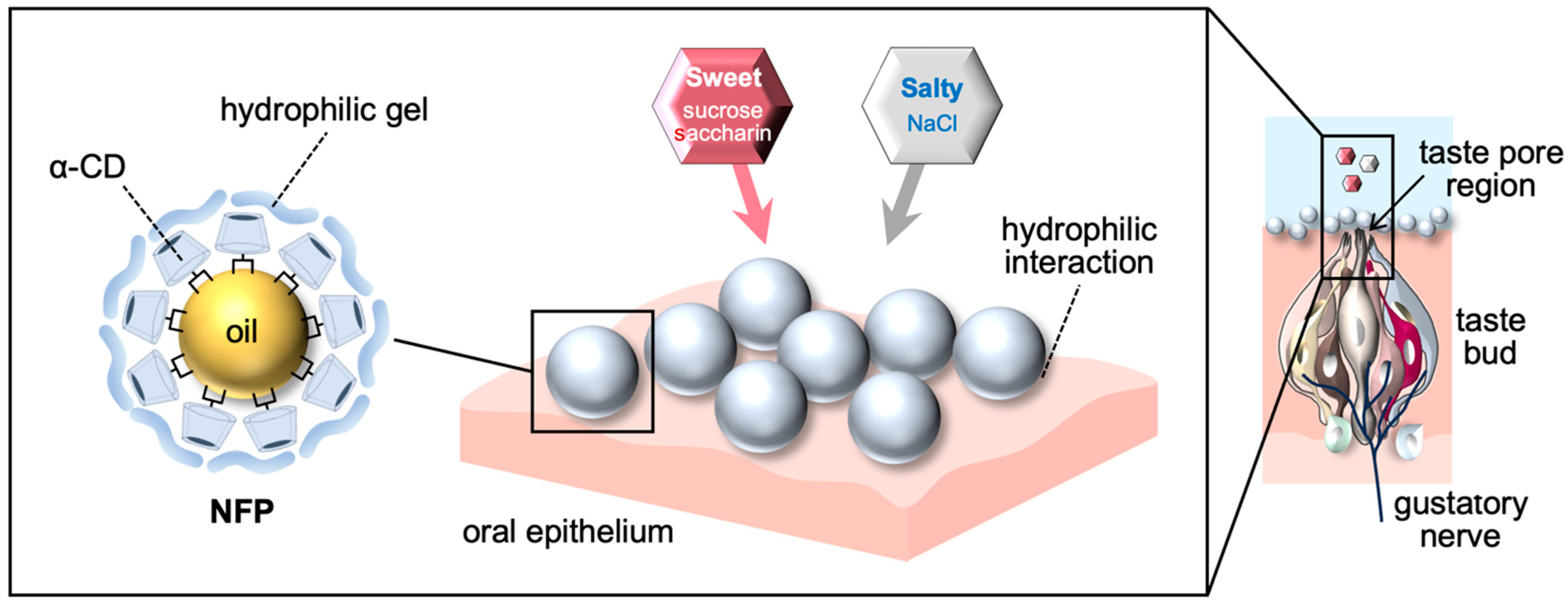

3.2.1. Mechanistic Considerations

3.2.2. Implications for Food Matrix-Based Modulation

3.2.3. Limitations

3.2.4. Future Directions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, G.A.; Nielsen, S.J.; Popkin, B.M. Consumption of High-Fructose Corn Syrup in Beverages May Play a Role in the Epidemic of Obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, J.; Jewell, J.; Keller, A. The Importance of the World Health Organization Sugar Guidelines for Dental Health and Obesity Prevention. Caries Res. 2019, 53, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Peterson, K.E.; Gortmaker, S.L. Relation between Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Drinks and Childhood Obesity: A Prospective, Observational Analysis. Lancet 2001, 357, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Fahimi, S.; Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Engell, R.E.; Lim, S.; Danaei, G.; Ezzati, M.; Powles, J. Global Sodium Consumption and Death from Cardiovascular Causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Global Report on Sodium Intake Reduction; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; ISBN 9789240069985. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Obesity and Overweight. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- WHO. Healthy Diet. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Graham, A.M.; Kawther, M.H. Action on Sugar--Lessons from UK Salt Reduction Programme. Lancet 2014, 383, 929–931. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.S.; Mars, M.; James, J.; de Graaf, K.; Appleton, K.M. Sweet Talk: A Qualitative Study Exploring Attitudes towards Sugar, Sweeteners and Sweet-Tasting Foods in the United Kingdom. Foods 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jachimowicz-Rogowska, K.; Winiarska-Mieczan, A. Initiatives to Reduce the Content of Sodium in Food Products and Meals and Improve the Population’s Health. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunteman, A.N.; McKenzie, E.N.; Yang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.Y. Compendium of Sodium Reduction Strategies in Foods: A Scoping Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1300–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmilah, S.; Cahyana, Y.; Utama, G.L.; Aït-Kaddour, A. Strategies to Reduce Salt Content and Its Effect on Food Characteristics and Acceptance: A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.J.; Huster, G.A.; Baker, S.L.; Milgrom, L.B.; Kirchgassner, A.; Birt, J.; Pressler, M.L. Characterization of the Precipitants of Hospitalization for Heart Failure Decompensation. Am. J. Crit. Care 1998, 7, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.M.; Rich, M.W.; Sperry, J.C.; Shah, A.S.; McNamara, T. Early Readmission of Elderly Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1990, 38, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, E.J.; Viscoli, C.M.; Horwitz, R.I. The Relationship of Treatment Adherence to the Risk of Death after Myocardial Infarction in Women. JAMA 1993, 270, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, C.J.; Wu, J.; Tu, W.; Young, J.; Murray, M.D. Association of Medication Adherence, Knowledge, and Skills with Emergency Department Visits by Adults 50 Years or Older with Congestive Heart Failure. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2004, 61, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.; Lennie, T.A.; Moser, D.K.; Okoli, C. Heart Failure Patients’ Perceptions on Nutrition and Dietary Adherence. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2009, 8, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.E.; Premathilake, H.U.; Yao, Q.; Mazucanti, C.H.; Egan, J.M. Physiology of the Tongue with Emphasis on Taste Transduction. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1193–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruno, A.; Gordon, M.D. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Salt Taste. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benucci, I.; Lombardelli, C.; Esti, M. A Comprehensive Review on Natural Sweeteners: Impact on Sensory Properties, Food Structure, and New Frontiers for Their Application. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 65, 4615–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.-P.; Wang, Y.; Munger, S.D.; Tang, X. A Review on Natural Sweeteners, Sweet Taste Modulators and Bitter Masking Compounds: Structure-Activity Strategies for the Discovery of Novel Taste Molecules. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 2076–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Inui-Yamamoto, C. The Flavor-Enhancing Action of Glutamate and Its Mechanism Involving the Notion of Kokumi. npj Sci. Food 2023, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wangzhang, J.; Sun, M.; Feng, T.; Liu, Q.; Yao, L.; Ho, C.-T.; Yu, C. Taste-Active Peptides from Triple-Enzymatically Hydrolyzed Straw Mushroom Proteins Enhance Salty Taste: An Elucidation of Their Effect on the T1R1/T1R3 Taste Receptor via Molecular Docking. Foods 2024, 13, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Qi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, J.; Yang, X. Enhancement of Sodium Salty Taste Modulate by Protease-Hydrolyzed Gum Arabic. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 141, 108759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, G.; San Miguel, R.; Hastings, R.; Chutasmit, P.; Trelokedsakul, A. Replication of the Taste of Sugar by Formulation of Noncaloric Sweeteners with Mineral Salt Taste Modulator Compositions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9469–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, Y.; Yasuda, R.; Kuroda, M.; Eto, Y. Kokumi Substances, Enhancers of Basic Tastes, Induce Responses in Calcium-Sensing Receptor Expressing Taste Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, K.; Shen, X.; Chen, P.; Tian, S.; Qin, Y.; Qi, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Subcritical Water-Extracted Soy Hull Polysaccharides: Relationship to Salty Taste of Sodium. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Soladoye, O.P.; Aluko, R.E.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Preparation, Receptors, Bioactivity and Bioavailability of γ-Glutamyl Peptides: A Comprehensive Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 113, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soejarto, D.D.; Addo, E.M.; Kinghorn, A.D. Highly Sweet Compounds of Plant Origin: From Ethnobotanical Observations to Wide Utilization. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 243, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana-Paucar, A.M. Steviol Glycosides from Stevia Rebaudiana: An Updated Overview of Their Sweetening Activity, Pharmacological Properties, and Safety Aspects. Molecules 2023, 28, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejtli, J. Introduction and General Overview of Cyclodextrin Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 1998, 98, 1743–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamoudi, M.C.; Bourasset, F.; Domergue-Dupont, V.; Gueutin, C.; Nicolas, V.; Fattal, E.; Bochot, A. Formulations Based on Alpha Cyclodextrin and Soybean Oil: An Approach to Modulate the Oral Release of Lipophilic Drugs. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizaki, K.; Kageyama, T.; Inoue, M.; Taguchi, H.; Ueda, H.; Saito, Y. Study on Preparation and Formation Mechanism of N-Alkanol:Water Emulsion Using a-Cyclodextrin. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, M.E.; Appelqvist, I.A.M.; Norton, I.T. Oral Behaviour of Food Hydrocolloids and Emulsions. Part 2. Taste and Aroma Release. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, W. An Overview of Pickering Emulsions: Solid-Particle Materials, Classification, Morphology, and Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho-Guimarães, F.B.; Correa, K.L.; de Souza, T.P.; Rodríguez Amado, J.R.; Ribeiro-Costa, R.M.; Silva-Júnior, J.O.C. A Review of Pickering Emulsions: Perspectives and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhao, K. Impact of Pulsation Rate and Viscosity on Taste Perception–Application of a Porous Medium Model for Human Tongue Surface. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Takai, S.; Sanematsu, K.; Yoshida, R.; Kawabata, F.; Shigemura, N. The Antiarrhythmic Drug Flecainide Enhances Aversion to HCl in Mice. eNeuro 2023, 10, ENEURO.0048-23.2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, S.; Yasumatsu, K.; Inoue, M.; Iwata, S.; Yoshida, R.; Shigemura, N.; Yanagawa, Y.; Drucker, D.J.; Margolskee, R.F.; Ninomiya, Y. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Is Specifically Involved in Sweet Taste Transmission. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2268–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, R.; Ohkuri, T.; Jyotaki, M.; Yasuo, T.; Horio, N.; Yasumatsu, K.; Sanematsu, K.; Shigemura, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Margolskee, R.F.; et al. Endocannabinoids Selectively Enhance Sweet Taste. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, N.; Iwata, S.; Yasumatsu, K.; Ohkuri, T.; Horio, N.; Sanematsu, K.; Yoshida, R.; Margolskee, R.F.; Ninomiya, Y. Angiotensin II Modulates Salty and Sweet Taste Sensitivities. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 6267–6277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Fushiki, T. Importance of Lipolysis in Oral Cavity for Orosensory Detection of Fat. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 285, R447–R454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordoff, M.G.; Bachmanov, A.A. Mouse Taste Preference Tests: Why Only Two Bottles? Chem. Senses 2003, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dany, G.; Jennifer, M.S. Measurement of Behavioral Taste Responses in Mice: Two-Bottle Preference, Lickometer, and Conditioned Taste-Aversion Tests. Curr. Protoc. 2016, 6, 380–407. [Google Scholar]

- Jadav, M.; Pooja, D.; Adams, D.J.; Kulhari, H. Advances in Xanthan Gum-Based Systems for the Delivery of Therapeutic Agents. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiledar, R.R.; Tagalpallewar, A.A.; Kokare, C.R. Formulation and in Vitro Evaluation of Xanthan Gum-Based Bilayered Mucoadhesive Buccal Patches of Zolmitriptan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baus, R.A.; Zahir-Jouzdani, F.; Dünnhaupt, S.; Atyabi, F.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Mucoadhesive Hydrogels for Buccal Drug Delivery: In Vitro-in Vivo Correlation Study. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 142, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jug, M.; Yoon, B.K.; Jackman, J.A. Cyclodextrin-Based Pickering Emulsions: Functional Properties and Drug Delivery Applications. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2021, 101, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadou, S.; El-Barghouthi, M.; Alabdallah, S.; Badwan, A.; Antonijevic, M.; Chowdhry, B. Effect of Protonation State and N-Acetylation of Chitosan on Its Interaction with Xanthan Gum: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.S.; Zografi, G. Sugar–Polymer Hydrogen Bond Interactions in Lyophilized Amorphous Mixtures. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehala; Baranwal, K.; Malviya, T.; Dwivedi, L.M.; Prabha, M.; Singh, V. Efficient Sensing of Saccharin through Interference Synthesis of Gum Ghatti Capped Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 2003–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fig. | Content | Analysis | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1A | Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP | n = 9 (Water), 9 (Ctrl), 9 (NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 26) = 0.094 | 0.911 | |

| S1B | Application (Ctrl vs. NFP) | n = 7 (Ctrl), 7 (NFP) | Unpaired t-test | Ctrl vs. NFP | 0.465 | |

| 1B | Sucrose 60 mM (Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP) | n = 4–6 (water), 5–6 (Ctrl), 5–6 (NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 15) = 6.501 | 0.011 | |

| Post hoc Tukey’s test | Water vs. Ctrl Water vs. NFP Ctrl vs. NFP | 0.845 0.041 0.014 | ||||

| 1C | NaCl 100 mM (Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 17) = 4.748 | 0.025 | ||

| Post hoc Tukey’s test | Water vs. Ctrl Water vs. NFP Ctrl vs. NFP | 0.996 0.040 0.047 | ||||

| 1D | CA 10 mM (Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 14) = 0.301 | 0.745 | ||

| 1E | QHCl 0.1 mM (Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 15) = 0.091 | 0.914 | ||

| 1F | MPG 100 mM (Water vs. Ctrl, Water vs. NFP, Ctrl vs. NFP) | One-way ANOVA | F (2, 14) = 0.484 | 0.628 | ||

| 2B | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [sucrose] | n = 6–8 (Ctrl), 6–7 (NFP) | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 39) = 17.503 F (2, 39) = 119.726 F (2, 39) = 2.890 | <0.001 <0.001 0.068 |

| Unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction | Ctrl vs. NFP | 100 mM sucrose 300 mM sucrose 1000 mM sucrose | 0.004 0.049 0.001 | |||

| 2C | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [saccharin] | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 39) = 5.984 F (2, 39) = 46.078 F (2, 39) = 1.369 | 0.019 <0.001 0.266 | |

| Unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction | Ctrl vs NFP | 3 mM saccharin 10 mM saccharin 30 mM saccharin | 0.232 0.041 0.019 | |||

| 2D | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [NaCl] | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 33) = 5.880 F (2, 33) = 32.584 F (2, 33) = 1.223 | 0.021 <0.001 0.307 | |

| Unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction | Ctrl vs NFP | 100 mM NaCl 300 mM NaCl 500 mM NaCl | 0.040 0.041 0.041 | |||

| 2E | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [citric acid] | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 22) = 0.109 F (1, 22) = 13.436 F (1, 22) = 0.156 | 0.744 0.001 0.696 | |

| 2F | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [QHCl] | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 20) = 0.606 F (1, 20) = 0.374 F (1, 20) = 0.038 | 0.445 0.548 0.848 | |

| 2G | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) × concentration [MPG] | Two-way ANOVA | Injection (Ctrl vs. NFP) Concentration Injection × concentration | F (1, 22) = 0.915 F (1, 22) = 20.611 F (1, 22) = 0.400 | 0.349 <0.001 0.534 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kawabata, Y.; Yamazoe, J.; Imamura, E.; Nagasato, Y.; Lee, Y.; Shinoda, M.; Koda, K.; Tomita, Y.; Ito, H.; Takai, S.; et al. A Novel Food-Derived Particle Enhances Sweet and Salty Taste Responses in Mice. Nutrients 2026, 18, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010098

Kawabata Y, Yamazoe J, Imamura E, Nagasato Y, Lee Y, Shinoda M, Koda K, Tomita Y, Ito H, Takai S, et al. A Novel Food-Derived Particle Enhances Sweet and Salty Taste Responses in Mice. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawabata, Yuko, Junichi Yamazoe, Emiko Imamura, Yuki Nagasato, Yihung Lee, Mami Shinoda, Kirari Koda, Yuki Tomita, Hina Ito, Shingo Takai, and et al. 2026. "A Novel Food-Derived Particle Enhances Sweet and Salty Taste Responses in Mice" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010098

APA StyleKawabata, Y., Yamazoe, J., Imamura, E., Nagasato, Y., Lee, Y., Shinoda, M., Koda, K., Tomita, Y., Ito, H., Takai, S., Sanematsu, K., Ogata, M., Kono, H., & Shigemura, N. (2026). A Novel Food-Derived Particle Enhances Sweet and Salty Taste Responses in Mice. Nutrients, 18(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010098