First Trimester Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Mexican Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

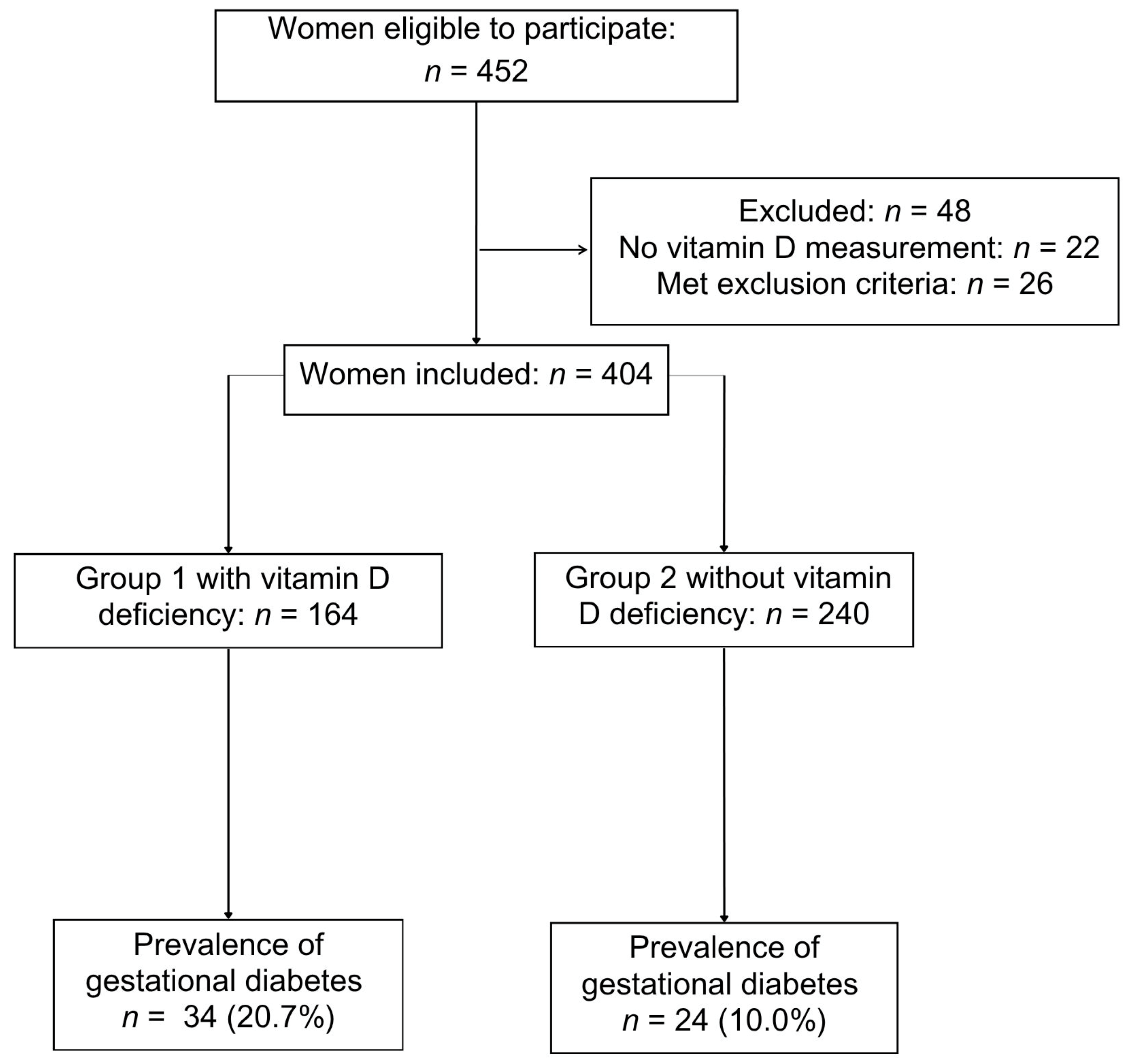

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Sample Size

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence Tools

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.2. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.3. Potential Biological Mechanisms

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APOs | Adverse Perinatal Outcomes |

| GDM | Gestational Diabetes Mellitus |

| OBESO | Biochemical and Epigenetic Origin of Overweight and Obesity |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| SGA | Small For Gestational Age |

| LGA | Large For Gestational Age |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

References

- Voiculescu, V.M.; Nelson Twakor, A.; Jerpelea, N.; Pantea Stoian, A. Vitamin D: Beyond Traditional Roles—Insights into Its Biochemical Pathways and Physiological Impacts. Nutrients 2025, 17, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, C.; Kostiuk, L.K.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD008873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Atkins, A.; Downes, M.; Wei, Z. Vitamin D in Diabetes: Uncovering the Sunshine Hormone’s Role in Glucose Metabolism and Beyond. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, R.; Sameen, A.; Murtaza, M.A.; Sharif, H.R.; Iahtisham-Ul-Haq; Dawood, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Nemat, A.; Manzoor, M.F. Impact of vitamin D on maternal and fetal health: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3230–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ajlan, A.; Al-Musharaf, S.; Fouda, M.A.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Wani, K.; Aljohani, N.J.; Al-Serehi, A.; Sheshah, E.; Alshingetti, N.M.; Turkistani, I.Z.; et al. Lower vitamin D levels in Saudi pregnant women are associated with higher risk of developing GDM. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, J.L.; Oliveri, B.; Giacoia, E.; Fusaro, D.; Costanzo, P.R. Vitamin D: Before, during and after Pregnancy: Effect on Neonates and Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Pan, G.T.; Guo, J.F.; Li, B.Y.; Qin, L.Q.; Zhang, Z.L. Vitamin D Deficiency Increases the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2015, 7, 8366–8375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf, R.; Morton, S.M.B.; Camargo, C.A.; Grant, C.C. Global summary of maternal and newborn vitamin D status—A systematic review. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2016, 12, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martínez, M.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Shamah-Levy, T. Nota técnica de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición Continua 2023: Resultados del trabajo de campo. Salud Publica Mex. 2024, 66, 304–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Liu, Z.B.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.C.; Fu, L.; Yu, Z.; Chen, W.; Song, Y.P.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; et al. Gestational vitamin D deficiency causes placental insufficiency and fetal intrauterine growth restriction partially through inducing placental inflammation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhou, L.; Wang, S.; Yin, H.; Yang, X.; Hao, L. Effect of maternal vitamin D status on risk of adverse birth outcomes: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 2881–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raia-Barjat, T.; Sarkis, C.; Rancon, F.; Thibaudin, L.; Gris, J.C.; Alfaidy, N.; Chauleur, C. Vitamin D deficiency during late pregnancy mediates placenta-associated complications. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprian, F.; Lefkou, E.; Varoudi, K.; Girardi, G. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D in Pregnancy and Beyond. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Z.; Qin, H. Vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of bacterial vaginosis during pregnancy: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1045357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Shi, Z.; Song, Q.; Cui, X.; Shen, L.; Qu, M.; Mai, S.; Zang, J. The Interactive Effects of Severe Vitamin D Deficiency and Iodine Nutrition Status on the Risk of Thyroid Disorder in Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z. Serum vitamin D deficiency and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milajerdi, A.; Abbasi, F.; Mousavi, S.M.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Maternal vitamin D status and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2576–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyden, E.L.; Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D: Effects on human reproduction, pregnancy, and fetal well-being. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 180, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Basto-Abreu, A.; López-Olmedo, N.; Rojas-Martínez, R.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Moreno-Banda, G.L.; Carnalla, M.; Rivera, J.A.; Romero-Martinez, M.; Barquera, S.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Prevalencia de prediabetes y diabetes en México: Ensanut 2022. Salud Publica Mex. 2023, 65, s163–s168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Mo, M.; Xin, X.; Jiang, W.; Wu, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, S.; Muyiduli, X.; Si, S.; Shen, Y.; et al. The interaction between prepregnancy BMI and gestational vitamin D deficiency on the risk of GDM subtypes. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2265–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, K.; Healy, M.; Crowley, V.; Louw, M.; Rochev, Y. Verification of Abbott 25-OH-vitamin D assay on the architect system. Pract. Lab. Med. 2017, 7, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElSayed, N.A.; McCoy, R.G.; Aleppo, G.; Balapattabi, K.; Beverly, E.A.; Briggs Early, K.; Bruemmer, D.; Ebekozien, O.; Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Ekhlaspour, L.; et al. 2. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S27–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Croke, L. Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: A Practice Bulletin from ACOG. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 649–650. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 171: Management of Preterm Labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, e155–e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutland, C.L.; Lackritz, E.M.; Mallett-Moore, T.; Bardají, A.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Lahariya, C.; Nisar, M.I.; Tapia, M.D.; Pathirana, J.; Kochhar, S.; et al. Low birth weight: Case definition & guidelines for maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Muñoz, E.; Martínez-Herrera, E.M.; Ortega-González, C.; Arce-Sánchez, L.; Ávila-Carrasco, A.; Zamora-Escudero, R. HOMA-IR and QUICKI reference values during pregnancy in Mexican women. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 2017, 85, 306–313. [Google Scholar]

- Rajput, R.; Vohra, S.; Nanda, S.; Rajput, M. Severe 25(OH)vitamin-D deficiency: A risk factor for GDM development. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2019, 13, 985–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero-Domenech, N.; Jover, S.; Sarrión, A.; Baranda, J.; Quesada-Rico, J.A.; Pereira-Expósito, A.; Gil-Guillén, V.; Cortés-Castell, E.; García-Teruel, M.J. Vitamin D Deficiency and GDM in Relation to BMI. Nutrients 2021, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiefari, E.; Pastore, I.; Puccio, L.; Caroleo, P.; Oliverio, R.; Vero, A.; Foti, D.P.; Vero, R.; Brunetti, A. Impact of Seasonality on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2017, 17, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.; Şahin Ersoy, G.; Demirtaş, Ö.; Kurt, S.; Taşyurt, A. Vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and GDM risk in low-risk women. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2016, 13, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, S.; Zittermann, A.; Obeid, R.; Hahn, A.; Pludowski, P.; Trummer, C.; Lerchbaum, E.; Pérez-López, F.R.; Karras, S.N.; März, W. The Role of Vitamin D in Fertility and during Pregnancy and Lactation: A Review of Clinical Data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; Choi, M.Y.; Longtine, M.S.; Nelson, D.M. Vitamin D Effects on Pregnancy and the Placenta. Placenta 2010, 31, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Drzewoski, J.; Śliwińska, A. The Molecular Mechanisms by Which Vitamin D Prevents Insulin Resistance and Associated Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczak-Pajor, I.; Śliwińska, A. Analysis of Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, M.; Battista, M.-C.; Doyon, M.; Houde, G.; Ménard, J.; Ardilouze, J.-L.; Hivert, M.-F.; Perron, P. Lower Vitamin D Levels at First Trimester Are Associated with Higher Risk of Developing Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Xue, H.; Xiong, J.; Cheng, G. Vitamin D and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review Based on Data Free of Hawthorne Effect. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 125, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, F.; Cianferotti, L.; Di Monaco, M.; Falchetti, A.; Fassio, A.; Gatti, D.; Gennari, L.; Giannini, S.; Girasole, G.; Gonnelli, S.; et al. Definition, Assessment, and Management of Vitamin D Inadequacy: Suggestions, Recommendations, and Warnings from the Italian Society for Osteoporosis, Mineral Metabolism and Bone Diseases (SIOMMMS). Nutrients 2022, 14, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D status: Measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, M.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Bikle, D.D.; Diab, D.L.; Kiely, M.E.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Lips, P.; Mitchell, D.M.; Murad, M.H.; Powers, S.; et al. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1907–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tous, M.; Villalobos, M.; Iglesias, L.; Fernández-Barrés, S.; Arija, V. Vitamin D status during pregnancy and offspring outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 164) | No Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 240) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.2 ± 5.5 | 29.9 ± 5.3 | 0.579 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 28.53 ± 5.90 | 26.74 ± 4.93 | 0.002 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 75.8 ± 20 | 74.7 ± 21 | 0.980 |

| Insulin (mcUI/mL) | 14.2 ± 18.3 | 14.4 ± 2.4 | 0.898 |

| HOMA-IR Index | 2.09 ± 2.39 | 1.95 ± 2.46 | 0.586 |

| Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR > 1.6) | 69 (42.07%) | 89 (37.08%) | 0.419 |

| Vitamin D concentration (ng/mL) | 15.9 ± 3.23 | 26.24 ± 4.76 | 0.0001 |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.99 kg/m2) | 55 (33.5%) | 97 (41.6%) | 0.195 |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2) | 52 (31.7%) | 80 (34.3%) | 0.815 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 57 (34.8%) | 56 (24.0%) | 0.016 |

| Primigravida | 98 (59.8%) | 136 (56.7%) | 0.607 |

| Multigravida | 66 (40.2%) | 104 (43.3%) | 0.607 |

| Autumn-Winter | 91 (55.5%) | 106 (44.2) | 0.025 |

| Spring-Summer | 73 (44.5%) | 134 (55.8%) | 0.025 |

| Characteristic | Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 164) | No Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 240) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.1 ± 1.8 | 38.4 ± 1.6 | 0.103 |

| Weight of newborn (g) | 2957 ± 472 | 3013 ± 436 | 0.253 |

| Height of Newborn (cm) | 47.7 ± 2.9 | 48.3 ± 2.6 | 0.252 |

| Gestational age at OGTT | 24.4 ± 5.2 | 24.2 ± 5.3 | 0.655 |

| Glucose Values during OGTT | |||

| - Fasting (mg/dL) | 80.0 ± 10.5 | 78.6 ± 8.6 | 0.129 |

| - 1 h (mg/dL) | 133.6 ± 39.1 | 122.9 ± 32.7 | 0.003 |

| - 2 h (mg/dL) | 114.8 ± 28.9 | 105 ± 26.1 | 0.001 |

| Vitamin D supplementation 1T or 2T | 113 (40.9%) | 178 (43.8%) | 0.563 |

| Vitamin D supplementation doses (IU) | 250 (250–500) * | 250 (250–500) * | 0.165 ** |

| Aspirin started before 17 weeks of gestation | 51 (31.1%) | 63 (26.3%) | 0.226 |

| Metformin started during 1T or 2T | 20 (12.2%) | 16 (6.6%) | 0.055 |

| Adverse Perinatal Outcome | Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 164) | No Vitamin D Deficiency (n = 240) | aOR * (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miscarriage | 1 (0.6%) | 7 (2.9%) | 0.19 (0.02–1.63) | 0.09 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 34 (20.7%) | 24 (10.0%) | 2.04 (1.14–3.65) | 0.01 |

| Preterm birth | 23 (14.0%) | 22 (9.2%) | 1.44 (0.76–2.52) | 0.25 |

| Preeclampsia | 20 (12.1%) | 18 (7.5%) | 1.55 (0.77–3.11) | 0.21 |

| Gestational hypertension | 4 (2.4%) | 13 (5.4%) | 0.36 (0.11–1.17) | 0.14 |

| Cesarean delivery | 91 (55.48%) | 137 (57.1%) | 0.83 (0.55–1.26) | 0.39 |

| Neonates large for gestational age | 8 (4.9%) | 9 (3.8%) | 1.11 (0.41–3.0) | 0.84 |

| Neonates small for gestational age | 14 (8.5%) | 16 (6.7%) | 1.27 (0.59–2.7) | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arce-Sánchez, L.; González-Ludlow, I.; Lizano-Jubert, I.; Almada-Balderrama, J.A.; Suárez-Rico, B.V.; Montoya-Estrada, A.; Estrada-Gutierrez, G.; Sánchez-Martinez, M.; Solis-Paredes, J.M.; Torres-Torres, J.; et al. First Trimester Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Mexican Cohort. Nutrients 2026, 18, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010097

Arce-Sánchez L, González-Ludlow I, Lizano-Jubert I, Almada-Balderrama JA, Suárez-Rico BV, Montoya-Estrada A, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Sánchez-Martinez M, Solis-Paredes JM, Torres-Torres J, et al. First Trimester Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Mexican Cohort. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleArce-Sánchez, Lidia, Isabel González-Ludlow, Ileana Lizano-Jubert, Jocelyn Andrea Almada-Balderrama, Blanca Vianey Suárez-Rico, Araceli Montoya-Estrada, Guadalupe Estrada-Gutierrez, Maribel Sánchez-Martinez, Juan Mario Solis-Paredes, Johnatan Torres-Torres, and et al. 2026. "First Trimester Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Mexican Cohort" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010097

APA StyleArce-Sánchez, L., González-Ludlow, I., Lizano-Jubert, I., Almada-Balderrama, J. A., Suárez-Rico, B. V., Montoya-Estrada, A., Estrada-Gutierrez, G., Sánchez-Martinez, M., Solis-Paredes, J. M., Torres-Torres, J., Rodríguez-Cano, A. M., Tolentino-Dolores, M., Perichart-Perera, O., Villegas-Soto, M., & Reyes-Muñoz, E. (2026). First Trimester Vitamin D Deficiency and Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Mexican Cohort. Nutrients, 18(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010097