Application of the China Diet Balance Index (DBI-2022) in a Region with a High-Quality Dietary Pattern and Its Association with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Lingnan Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Assess the applicability of the DBI-2022 in a region with a traditionally high-quality diet, specifically evaluating its sensitivity in distinguishing health outcomes among populations with high baseline dietary quality.

- (2)

- Quantify dietary quality and examine the relationship between dietary imbalance—encompassing both deficiency and excess—and hypertension.

- (3)

- Identify the specific food components that constitute the strengths and deficits of the Lingnan dietary pattern, thereby providing empirical evidence for the development of regionalized, precision nutrition intervention strategies.

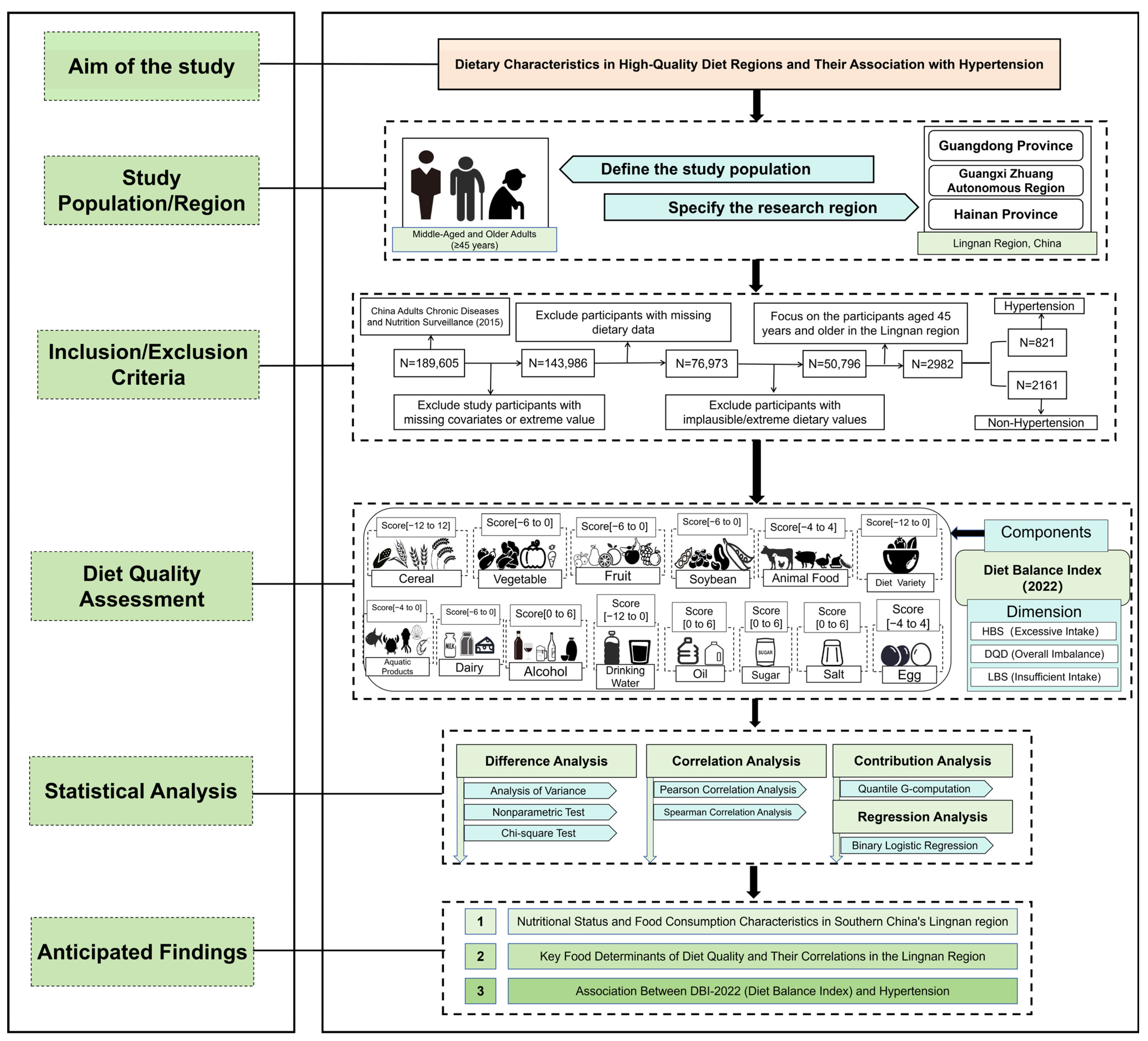

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

- (1)

- Missing key sociodemographic information (e.g., age, gender, or place of residence);

- (2)

- Incomplete physical examination records, specifically the lack of valid measurements for blood pressure, height, or weight;

- (3)

- Missing data on lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity) or history of hypertension diagnosis;

- (4)

- Missing or extreme dietary data.

2.2. Data Collection and Nutritional Assessment

- (1)

- Vigorous Intensity: Activities that cause a significant increase in breathing or heart rate and are sustained for at least 10 min.

- (2)

- Moderate Intensity: Activities that cause a mild increase in breathing or heart rate and are sustained for at least 10 min.

2.3. Definition of Hypertension

2.4. Dietary Quality Assessment

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- (1)

- Model 1: Unadjusted.

- (2)

- Model 2: Adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, marital status, residence, education level, ethnicity, and household income.

- (3)

- Model 3 (Fully Adjusted Model): Further adjusted for lifestyle and health-related factors, including family history of chronic diseases, BMI category, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption, multimorbidity, and polypharmacy.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

3.2. Distribution of Participants Across DBI-2022 Categories

3.3. DBI-2022 Scores and Dietary Intake Characteristics

3.4. Contribution of Dietary Components to DBI-2022 Scores

3.5. Correlation Analysis

3.6. Association Between DBI-2022 and Hypertension

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence and Correlates of Dietary Imbalance in Lingnan

4.2. Association Between Dietary Quality and Hypertension

4.3. Interaction of Lifestyle and Urbanization

4.4. Key Dietary Indicators and Potential Biological Mechanisms

4.5. The Inverse Association of Refined Cereals, Oil, and Salt with Dietary Quality

4.6. Suggestions for Regional Nutritional Strategies

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnier, M.; Damianaki, A. Hypertension as Cardiovascular Risk Factor in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 1050–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Ding, G.; Wang, Y. Trends in major non-communicable diseases and related risk factors in China 2002–2019: An analysis of nationally representative survey data. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 43, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, L.; Tian, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zheng, C.; et al. Status of Hypertension in China: Results From the China Hypertension Survey 2012–2015. Circulation 2018, 137, 2344–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Han, G.; Peng, K.; Li, X.; et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China, 2004–2018: Findings from six rounds of a national survey. BMJ 2023, 380, e071952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljuraiban, G.S.; Gibson, R.; Chan, D.S.; Van Horn, L.; Chan, Q. The Role of Diet in the Prevention of Hypertension and Management of Blood Pressure: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Interventional and Observational Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndanuko, R.N.; Tapsell, L.C.; Charlton, K.E.; Neale, E.P.; Batterham, M.J. Dietary Patterns and Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Pannucci, T.E.; Subar, A.F.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Lerman, J.L.; Tooze, J.A.; Wilson, M.M.; Reedy, J. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1591–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Arvaniti, F.; Stefanadis, C. Adherence to the Mediterranean food pattern predicts the prevalence of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes and obesity, among healthy adults; the accuracy of the MedDietScore. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhai, F.; Yang, X.; Ge, K. The Chinese diet balance index revised. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2009, 31, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society, C.N. Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents, 2022; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lăcătușu, C.M.; Grigorescu, E.D.; Floria, M.; Onofriescu, A.; Mihai, B.M. The Mediterranean Diet: From an Environment-Driven Food Culture to an Emerging Medical Prescription. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantonese Dietary Pattern Expert Group. An Introduction to the cantonese dietary pattern. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2023, 45, 417–421. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Sun, L.; Wu, Q.; Song, B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, P.; Niu, Z.; Zheng, H.; Li, H.; et al. Diet-Related Lipidomic Signatures and Changed Type 2 Diabetes Risk in a Randomized Controlled Feeding Study With Mediterranean Diet and Traditional Chinese or Transitional Diets. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zeng, X.; Wang, H.; Yin, P.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Qi, J.; Ran, S.; et al. Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases in China, 1990–2016: Findings From the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, W.S.; Jiang, C.Q.; Jin, Y.L.; Au Yeung, S.L.; Woo, J.; Cheng, K.K.; Lam, T.H.; Xu, L. Association of Cantonese dietary patterns with mortality risk in older Chinese: A 16-year follow-up of a Guangzhou Biobank cohort study. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 4538–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, L.; Gu, W.; Zong, G.; Song, B.; Shen, C.; Zhou, P.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. Isocaloric-restricted Mediterranean Diet and Chinese Diets High or Low in Plants in Adults With Prediabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, 2216–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Li, X.; Cui, Y.; Luan, D.; Li, S.J. Evaluation on the dietary quality of adult residents in Liaoning Province by Chinese diet balance index. Chin. J. Health Educ. 2020, 36, 880–884. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, M.-R.; Tang, J.-L.; Lu, Z.-L.; Yang, Y.-X.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Ren, T.-M.; Yin, Z.-X.; Ma, J.-X. Evaluation of dietary quality among adult residents in Shandong Province by the Chinese dietary balance index. Mod. Prev. Med. 2023, 50, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Ma, J.; Wen, J.; Peng, J.; Huang, P.; Zeng, L.; Chen, S.; Ji, G.; Yang, X.; Wu, W. Trends in Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods Among Adults in Southern China: Analysis of Serial Cross-Sectional Health Survey Data 2002–2022. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Gong, W.; Ding, C.; Song, C.; Yuan, F.; Fan, J.; Feng, G.; Chen, Z.; Liu, A. The association between frequency of eating out with overweight and obesity among children aged 6–17 in China: A National Cross-sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, Z. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption Associated with Incident Hypertension among Chinese Adults-Results from China Health and Nutrition Survey 1997–2015. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Balaji, B.; Tinajero, M.; Jarvis, S.; Khan, T.; Vasudevan, S.; Ranawana, V.; Poobalan, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.; Sun, Q.; et al. White rice, brown rice and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e065426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, F.Y.; Du, S.F.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, J.G.; Du, W.W.; Popkin, B.M. Dynamics of the Chinese diet and the role of urbanicity, 1991–2011. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2014, 15, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaboli, M.C.; Ocvirk, S.; Khan Mirzaei, M.; Eberhart, B.L.; Valdivia-Garcia, M.; Metwaly, A.; Neuhaus, K.; Barker, G.; Ru, J.; Nesengani, L.T.; et al. Diet changes due to urbanization in South Africa are linked to microbiome and metabolome signatures of Westernization and colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Cao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Yan, P.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; et al. Landscape of the gut archaeome in association with geography, ethnicity, urbanization, and diet in the Chinese population. Microbiome 2022, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Rahman, A.A.; Lee, S.; Malhotra, R. The Implications of Aging on Vascular Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L.; Huang, J.; Fang, H.; Guo, Q.; Xu, X.; Ju, L.; et al. China Nutrition and Health Surveys (1982–2017). China CDC Wkly. 2021, 3, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. 2018 Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension-A report of the Revision Committee of Chinese Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 182–241. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xia, J. Update of the Chinese Diet Balance Index: DBI_16. Acta Nutr. Sin. 2018, 40, 526–530. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhao, C. Association of diet quality and quantity with the risk of sarcopenia based on the Chinese diet balance index 2022. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1562362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Lu, F.C. The Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Overweight and Obesity in Chinese Adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2004, 17, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, J.M.; Rose, S.; Mortimer, K.M. Implementation of G-computation on a simulated data set: Demonstration of a causal inference technique. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Wang, L.; Xue, R.; Liu, Q.; Gao, S.; Yang, G.; Chen, S. Evaluation of dietary quality among residents in Wenzhou City by diet balance index. Prev. Med. 2024, 36, 359–361. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, X. Evaluation on the dietary quality of 18~64-year old residentsby adjusted diet balance index Guangzhou. Mod. Prev. Med. 2018, 45, 814–818. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Jin, Q. Measuring diet quality of Beijing 18–59 years adults using Chinese diet balance index. Cap. J. Public Health 2018, 12, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.F.; Wang, L.; Pan, A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, B.; Ding, G. Nutrition transition and related health challenges over decades in China. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Q.; Chen, C.; Bai, H.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Hao, Y. Trends and Characteristics of the Whole-Grain Diet. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 1969–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhong, F.; Li, J. The burden of cardiovascular disease attributable to dietary risk factors in China, 1990–2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; et al. Body-mass index and obesity in urban and rural China: Findings from consecutive nationally representative surveys during 2004–2018. Lancet 2021, 398, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Shen, Z.; Gu, W.; Lyu, Z.; Qi, X.; Mu, Y.; Ning, Y. Prevalence of obesity and associated complications in China: A cross-sectional, real-world study in 15.8 million adults. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2023, 25, 3390–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhao, L.; Chen, C.; Ren, Z.; Jing, Y.; Qiu, J.; Liu, D. National burden and risk factors of diabetes mellitus in China from 1990 to 2021: Results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2021. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; MacDonald, G.K.; Galloway, J.N.; Geng, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S. A new dietary guideline balancing sustainability and nutrition for China’s rural and urban residents. iScience 2022, 25, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, W.; Song, H.; Nie, F.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Bi, J.; Cong, W. Transforming Chinese Food Systems for Both Human and Planetary Health. In Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation; Von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L.O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 779–798. [Google Scholar]

- Huseynov, S.; Palma, M.A. Food decision-making under time pressure. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, H.G.; Davies, I.G.; Richardson, L.D.; Stevenson, L. Determinants of takeaway and fast food consumption: A narrative review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, A. Long-Term Diet Quality and Risk of Diabetes in a National Survey of Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Zhai, J.; Xu, M.; Zhu, X.; Ullah, A.; Lyu, Q. Association of diet quality with the risk of Sarcopenia based on the Chinese diet balance index 2016: A cross-sectional study among Chinese adults in Henan Province. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, N.; Fu, C. Unfavorable Dietary Quality Contributes to Elevated Risk of Ischemic Stroke among Residents in Southwest China: Based on the Chinese Diet Balance Index 2016 (DBI-16). Nutrients 2022, 14, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Tian, Z.; Zhao, D.; Li, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Fan, D.; Ma, X.; Ling, W.; et al. Associations between Adherence to Four A Priori Dietary Indexes and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors among Hyperlipidemic Patients. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Jorquera, H.; Cid-Jofré, V.; Landaeta-Díaz, L.; Petermann-Rocha, F.; Martorell, M.; Zbinden-Foncea, H.; Ferrari, G.; Jorquera-Aguilera, C.; Cristi-Montero, C. Plant-Based Nutrition: Exploring Health Benefits for Atherosclerosis, Chronic Diseases, and Metabolic Syndrome-A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3244. [Google Scholar]

- Tischmann, L.; Adam, T.C.; Mensink, R.P.; Joris, P.J. Longer-term soy nut consumption improves vascular function and cardiometabolic risk markers in older adults: Results of a randomized, controlled cross-over trial. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héroux, M.; Janssen, I.; Lee, D.C.; Sui, X.; Hebert, J.R.; Blair, S.N. Clustering of unhealthy behaviors in the aerobics center longitudinal study. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2012, 13, 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- de Mello, G.T.; Thirunavukkarasu, S.; Jeemon, P.; Thankappan, K.R.; Oldenburg, B.; Cao, Y. Clustering of health behaviors and their associations with cardiometabolic risk factors among adults at high risk for type 2 diabetes in India: A latent class analysis. J. Diabetes 2024, 16, e13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, R.R.; Cowan, A.; Vernarelli, J.A. More to gain: Dietary energy density is related to smoking status in US adults. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z. Association between joint physical activity and healthy dietary patterns and hypertension in US adults: Cross-sectional NHANES study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reily, N.M.; Pinkus, R.T.; Vartanian, L.R.; Faasse, K. Compensatory eating after exercise in everyday life: Insights from daily diary studies. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282501. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.S.; Guelfi, K.J.; Dimmock, J.A.; Jackson, B. Preliminary Validation of the Exercise-Snacking Licensing Scale: Rewarding Exercise with Unhealthy Snack Foods and Drinks. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roerecke, M.; Kaczorowski, J.; Tobe, S.W.; Gmel, G.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Rehm, J. The effect of a reduction in alcohol consumption on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e108–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Federico, S.; Filippini, T.; Whelton, P.K.; Cecchini, M.; Iamandii, I.; Boriani, G.; Vinceti, M. Alcohol Intake and Blood Pressure Levels: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Nonexperimental Cohort Studies. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, N.; Paul, C.; Turon, H.; Oldmeadow, C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the clustering of Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical activity (‘SNAP’) health risk factors. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Lu, H.; Wu, J.; Xue, M.; Qian, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, X. The interactive association between sodium intake, alcohol consumption and hypertension among elderly in northern China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021, 21, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, C.; Barilli, A.; Giuffredi, C.; Gatti, C.; Montanari, A.; Vescovi, P.P. Sodium sensitivity of blood pressure in long-term detoxified alcoholics. Hypertension 2000, 35, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonne, C.; Adair, L.; Adlakha, D.; Anguelovski, I.; Belesova, K.; Berger, M.; Brelsford, C.; Dadvand, P.; Dimitrova, A.; Giles-Corti, B.; et al. Defining pathways to healthy sustainable urban development. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milà, C.; Ranzani, O.; Sanchez, M.; Ambrós, A.; Bhogadi, S.; Kinra, S.; Kogevinas, M.; Dadvand, P.; Tonne, C. Land-Use Change and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in an Urbanizing Area of South India: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 47003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Z.H.; Cheong, H.C.; Tu, Y.K.; Kuo, P.H. Association between Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, H.; Sen, A.; Aune, D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1941–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torfadottir, J.E.; Ulven, S.M. Fish—A scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr. Res. 2024, 68, 10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shao, M.Y.; Jiang, C.Q.; Zhang, W.S.; Zhu, F.; Jin, Y.L.; Woo, J.; Cheng, K.K.; Lam, T.H.; Xu, L. Association of fish consumption with risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: An 11-year follow-up of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, B. Cellular antioxidant, methylglyoxal trapping, and anti-inflammatory activities of cocoa tea (Camellia ptilophylla Chang). Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2836–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, Y.; Lu, X.; Tao, F.; Tukhvatshin, M.; Xiang, F.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y. The Potential Mechanisms of Catechins in Tea for Anti-Hypertension: An Integration of Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Foods 2024, 13, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, R.; Huang, J.; Cai, Q.; Yang, C.S.; Wan, X.; Xie, Z. Effects and Mechanisms of Tea Regulating Blood Pressure: Evidences and Promises. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, K.; Shen, J.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Xiao, P. Huangqin Tea Total Flavonoids-Gut Microbiota Interactions: Based on Metabolome and Microbiome Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglio, C.; Chiavaro, E.; Visconti, A.; Fogliano, V.; Pellegrini, N. Effects of different cooking methods on nutritional and physicochemical characteristics of selected vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; You, L.; Wang, Y.; Luo, R. Effect of Traditional Stir-Frying on the Characteristics and Quality of Mutton Sao Zi. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 925208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Gu, X.; Imamura, F.; AlEssa, H.B.; Devinsky, O.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Manson, J.E.; Rimm, E.B.; Forouhi, N.G.; et al. Total and specific potato intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from three US cohort studies and a substitution meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. BMJ 2025, 390, e082121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Zhang, M.; Han, M.; Liu, D.; Luo, X.; Xu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; et al. Fried-food consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Heart 2021, 107, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Jin, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Bu, X.; Mu, J.; Lu, J. Global cardiovascular diseases burden attributable to high sodium intake from 1990 to 2019. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 25, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, P.; Cheng, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, J. Saturated Fatty Acid Intake Is Associated with Total Mortality in a Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Ding, G. Trends in dietary carbohydrates, protein and fat intake and diet quality among Chinese adults, 1991–2015: Results from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Cho, M.S. Geography of Food Consumption Patterns between South and North China. Foods 2017, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewey, K.G.; Adu-Afarwuah, S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 24–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemler, E.C.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Diets for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: All Plant Foods Are Not Created Equal. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2019, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sensitivity Analysis Scenario | Detailed Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Scenario 1: Exclusion of Prior Diagnosis | Exclude individuals with a prior diagnosis of hypertension. |

| Scenario 2: Exclusion of Medication Users | Exclude individuals with a prior diagnosis of hypertension who are currently using antihypertensive medications for blood pressure control. |

| Scenario 3: Exclusion of Lifestyle Modifications | Exclude individuals with a prior diagnosis of hypertension who are implementing non-pharmacological measures for hypertension control. |

| Scenario 4: Exclusion of Any Hypertension Control | Exclude individuals with a prior diagnosis of hypertension who are implementing any form of hypertension control measures. |

| Scenario 5: Exclusion of Control Behaviors | Exclude only those individuals who are implementing any form of hypertension control measures (regardless of diagnosis status). |

| Scenario 6: Exclusion of Other Interventions | Exclude individuals who are implementing dietary or exercise interventions specifically for the management of other chronic conditions. |

| Scenario 7: Exclusion of Lifestyle-Only Management | Exclude individuals who are managing hypertension exclusively through lifestyle modifications without the use of antihypertensive medication. |

| ALL n = 2982 | Non-Hypertension n = 2161 | Hypertension n = 821 | Test Statistic | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender [n (%)] | 7.554 | 0.006 | |||

| Female | 1569 (52.62%) | 1171 (54.19%) | 398 (48.48%) | ||

| Male | 1413 (47.38%) | 990 (45.81%) | 423 (51.52%) | ||

| Age(years) (M,P25,P75) | 58.58 [51.56;66.16] | 57.61 [50.95;64.94] | 61.70 [53.84;68.81] | −8.742 | <0.001 |

| Age Group [n (%)] | <0.001 | ||||

| 45–59 years | 1628 (54.59%) | 1270 (58.77%) | 358 (43.61%) | 58.723 | |

| 60–74 years | 1097 (36.79%) | 734 (33.97%) | 363 (44.21%) | ||

| ≥75 years | 257 (8.62%) | 157 (7.27%) | 100 (12.18%) | ||

| Ethnicity [n (%)] | 2.444 | 0.118 | |||

| Han Chinese | 2445 (81.99%) | 1787 (82.69%) | 658 (80.15%) | ||

| Other ethnic groups | 537 (18.01%) | 374 (17.31%) | 163 (19.85%) | ||

| Residence [n (%)] | 6.523 | 0.011 | |||

| Urban | 1177 (39.47%) | 822 (38.04%) | 355 (43.24%) | ||

| Rural | 1805 (60.53%) | 1339 (61.96%) | 466 (56.76%) | ||

| Education level [n (%)] | 2.411 | 0.300 | |||

| Primary school or below | 1678 (56.27%) | 1225 (56.69%) | 453 (55.18%) | ||

| Secondary or high school | 1201 (40.27%) | 868 (40.17%) | 333 (40.56%) | ||

| College or above | 103 (3.45%) | 68 (3.15%) | 35 (4.26%) | ||

| Marital status [n (%)] | 0.829 | 0.362 | |||

| Unmarried, widowed, divorced | 210 (7.04%) | 146 (6.76%) | 64 (7.80%) | ||

| Married, cohabiting, separated | 2772 (92.96%) | 2015 (93.24%) | 757 (92.20%) | ||

| Monthly income [n (%)] | 8.901 | 0.012 | |||

| <5000 CNY/month | 2241 (75.15%) | 1655 (76.58%) | 586 (71.38%) | ||

| 5000–9999 CNY/month | 540 (18.11%) | 366 (16.94%) | 174 (21.19%) | ||

| ≥10,000 CNY/month | 201 (6.74%) | 140 (6.48%) | 61 (7.43%) | ||

| Family history of chronic diseases [n (%)] | 793 (26.59%) | 502 (23.23%) | 291 (35.44%) | 44.849 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (M,P25,P75) | 23.09 [20.95;25.38] | 22.68 [20.71;24.86] | 24.46 [22.00;26.90] | −11.445 | <0.001 |

| BMI Level [n (%)] | <0.001 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 200 (6.71%) | 171 (7.91%) | 29 (3.53%) | 138.757 | |

| Normal (18.5–23.9 kg/m2) | 1588 (53.25%) | 1252 (57.94%) | 336 (40.93%) | ||

| Overweight (24.0–27.9 kg/m2) | 957 (32.09%) | 620 (28.69%) | 337 (41.05%) | ||

| Obese (≥28.0 kg/m2) | 237 (7.95%) | 118 (5.46%) | 119 (14.49%) | ||

| Adequate physical activity [n (%)] | 2103 (70.52%) | 1565 (72.42%) | 538 (65.53%) | 13.259 | <0.001 |

| Smoking [n (%)] | 790 (26.49%) | 591 (27.35%) | 199 (24.24%) | 2.797 | 0.094 |

| Drinking [n (%)] | 1008 (33.80%) | 723 (33.46%) | 285 (34.71%) | 0.366 | 0.545 |

| Multimorbidity [n (%)] | 557 (18.68%) | 80 (3.70%) | 477 (58.10%) | 1155.473 | <0.001 |

| Polypharmacy [n (%)] | 88 (2.95%) | 5 (0.23%) | 83 (10.11%) | 199.280 | <0.001 |

| HBS [ (SD)] | 22.58 (5.54) | 22.62 (5.58) | 22.47 (5.43) | 0.660 | 0.509 |

| LBS [ (SD)] | 40.48 (8.72) | 40.49 (8.69) | 40.44 (8.81) | 0.144 | 0.886 |

| DQD [ (SD)] | 63.06 (9.38) | 63.11 (9.38) | 62.91 (9.39) | 0.519 | 0.604 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, W.; Wen, J.; Zhang, X.; Gong, W.; Gan, P.; Huang, P.; Li, J.; Li, R.; Song, P.; Ding, G. Application of the China Diet Balance Index (DBI-2022) in a Region with a High-Quality Dietary Pattern and Its Association with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Lingnan Population. Nutrients 2026, 18, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010043

Dong W, Wen J, Zhang X, Gong W, Gan P, Huang P, Li J, Li R, Song P, Ding G. Application of the China Diet Balance Index (DBI-2022) in a Region with a High-Quality Dietary Pattern and Its Association with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Lingnan Population. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Weihua, Jian Wen, Xiaona Zhang, Weiyi Gong, Ping Gan, Panpan Huang, Jiaqi Li, Rongzhen Li, Pengkun Song, and Gangqiang Ding. 2026. "Application of the China Diet Balance Index (DBI-2022) in a Region with a High-Quality Dietary Pattern and Its Association with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Lingnan Population" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010043

APA StyleDong, W., Wen, J., Zhang, X., Gong, W., Gan, P., Huang, P., Li, J., Li, R., Song, P., & Ding, G. (2026). Application of the China Diet Balance Index (DBI-2022) in a Region with a High-Quality Dietary Pattern and Its Association with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Lingnan Population. Nutrients, 18(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010043