Nutritional Status, Body Composition and Growth in Paediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

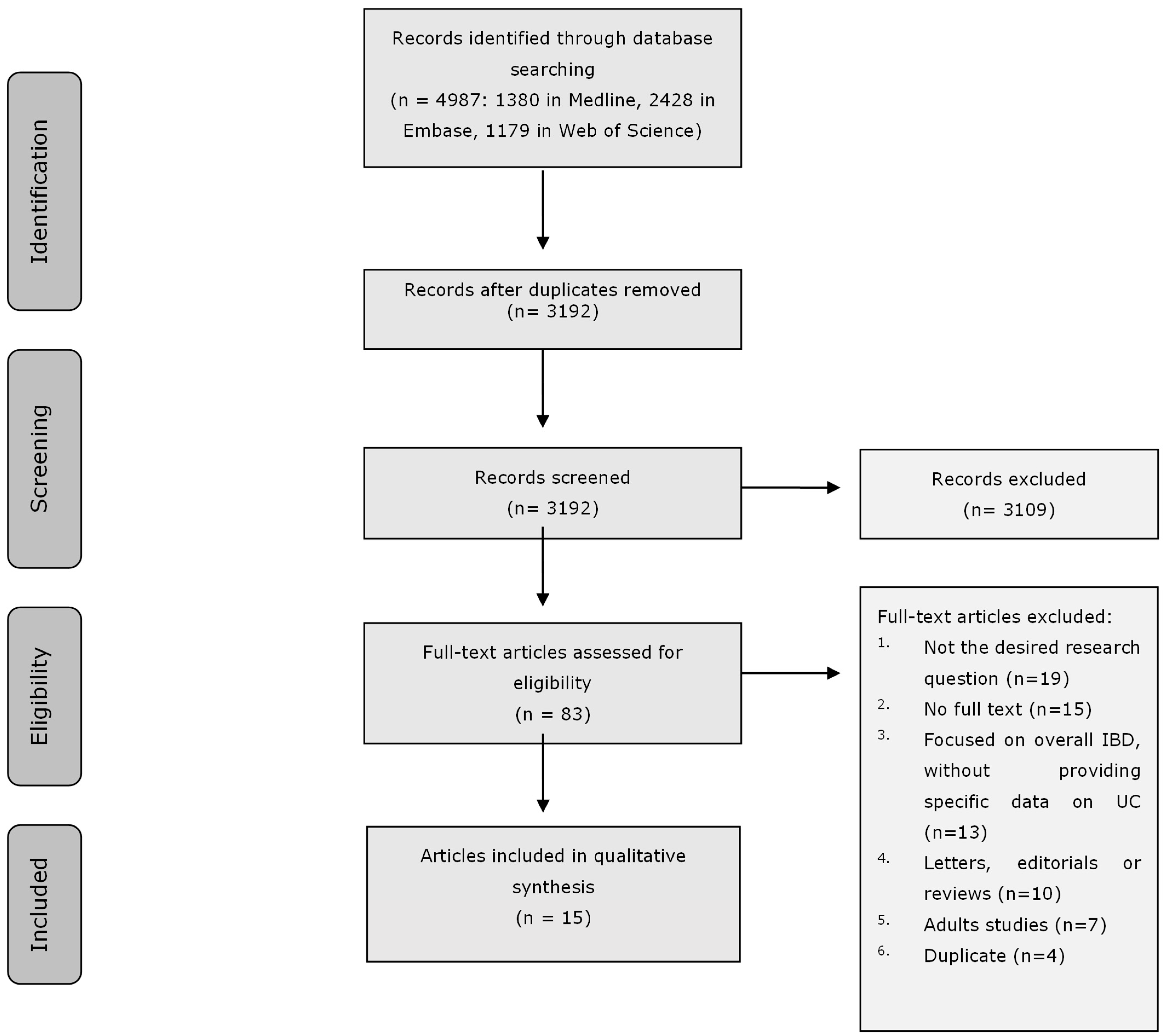

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study and Patient Characteristics

3.3. Methodology Assessment of the Outcomes

3.4. Systematic Evaluation of Growth and Nutritional Status

3.5. Systematic Evaluation of Body Composition

3.6. Quality Assessment

3.7. Results of Syntheses

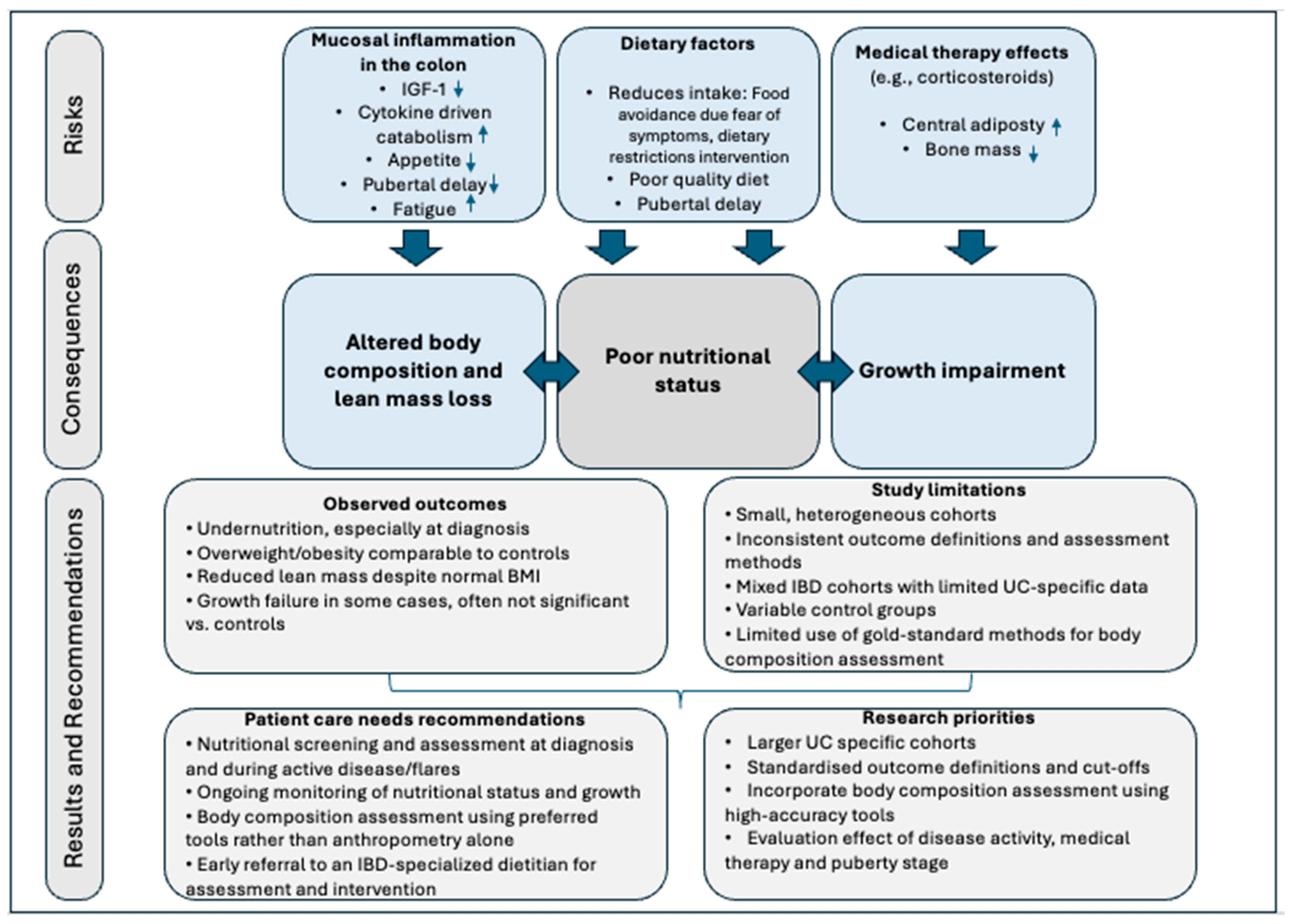

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hill, R.J. Update on nutritional status, body composition and growth in paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 3191–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Bager, P.; Escher, J.; Forbes, A.; Hebuterne, X.; Hvas, C.L.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ockenga, J.; et al. ESPEN guideline on Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ding, X.; Maggiore, G.; Pietrobattista, A.; Satapathy, S.K.; Tian, Z.; Jing, X. Sarcopenia is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective cohort study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Kirchner, H.; Lochs, H.; Pirlich, M. Malnutrition affects quality of life in gastroenterology patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 3380–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A.C.; Moosa, A.; Lomer, M.C.; Reidlinger, D.P.; Whelan, K. Variable access to quality nutrition information regarding inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of patients and health professionals and objective examination of written information. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assa, A.; Aloi, M.; Van Biervliet, S.; Bronsky, J.; di Carpi, J.M.; Gasparetto, M.; Gianolio, L.; Gordon, H.; Hojsak, I.; Hudson, A.S.; et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 2: Acute severe colitis-An updated evidence-based consensus guideline from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2025, 81, 816–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rheenen, P.F.; Aloi, M.; Assa, A.; Bronsky, J.; Escher, J.C.; Fagerberg, U.L.; Gasparetto, M.; Gerasimidis, K.; Griffiths, A.; Henderson, P.; et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J. Crohns. Colitis 2021, 15, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangarajah, D.; Hyde, M.J.; Konteti, V.K.; Santhakumaran, S.; Frost, G.; Fell, J.M. Systematic review: Body composition in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houttu, N.; Kalliomaki, M.; Gronlund, M.M.; Niinikoski, H.; Nermes, M.; Laitinen, K. Body composition in children with chronic inflammatory diseases: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2647–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swirkosz, G.; Szczygiel, A.; Logon, K.; Wrzesniewska, M.; Gomulka, K. The Role of the Microbiome in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis—A Literature Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.L.; Christophersen, C.T.; Bird, A.R.; Conlon, M.A.; Rosella, O.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. Abnormal fibre usage in UC in remission. Gut 2015, 64, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.K.; Sarbagili-Shabat, C. Gaseous metabolites as therapeutic targets in ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Limbergen, J.; Russell, R.K.; Drummond, H.E.; Aldhous, M.C.; Round, N.K.; Nimmo, E.R.; Smith, L.; Gillett, P.M.; McGrogan, P.; Weaver, L.T.; et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wine, E.; Aloi, M.; Van Biervliet, S.; Bronsky, J.; di Carpi, J.M.; Gasparetto, M.; Gianolio, L.; Gordon, H.; Hojsak, I.; Hudson, A.S.; et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 1: Ambulatory care-An updated evidence-based consensus guideline from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2025, 81, 765–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.; Isaac, D.M.; Wine, E. Growth Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Significance, Causes, and Management. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svolos, V.; Gordon, H.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Aloi, M.; Bancil, A.; Day, A.S.; Day, A.S.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; Gerasimidis, K.; Gkikas, K.; et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation consensus on dietary management of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohns. Colitis 2025, 19, jjaf122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.W.; Gurwara, S.; Silver, H.J.; Horst, S.N.; Beaulieu, D.B.; Schwartz, D.A.; Seidner, D.L. Sarcopenia Is Common in Overweight Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and May Predict Need for Surgery. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Aziz, M.A.; Hubner, M.; Demartines, N.; Larson, D.W.; Grass, F. Simple Clinical Screening Underestimates Malnutrition in Surgical Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease-An ACS NSQIP Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.V.; Ooi, S.; Schultz, C.G.; Goess, C.; Grafton, R.; Hughes, J.; Lim, A.; Bartholomeusz, F.D.; Andrews, J.M. Low muscle mass and sarcopenia: Common and predictive of osteopenia in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PROSPERO: International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. University of York. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Otten, R.; de Vries, R.; Schoonmade, L. Amsterdam Efficient Deduplication (AED) method—Manual. Zenodo.org. 2019. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4544315 (accessed on 27 December 2025).

- Bramer, W.M.; Giustini, D.; de Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishige, T. Growth failure in pediatric onset inflammatory bowel disease: Mechanisms, epidemiology, and management. Transl. Pediatr. 2019, 8, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.L.; Correia, M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.S.; Tassone, D.; Al Bakir, I.; Wu, K.; Thompson, A.J.; Connell, W.R.; Malietzis, G.; Lung, P.; Singh, S.; Choi, C.R.; et al. Systematic Review: The Impact and Importance of Body Composition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns. Colitis 2022, 16, 1475–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: North Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Assa, A.; Assayag, N.; Balicer, R.D.; Gabay, H.; Greenfeld, S.; Kariv, R.; Ledderman, N.; Matz, E.; Dotan, I.; Ledder, O.; et al. Pediatric-onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease Has Only a Modest Effect on Final Growth: A Report From the epi-IIRN. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 73, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motil, K.J.; Grand, R.J.; Davis-Kraft, L.; Ferlic, L.L.; Smith, E.O. Growth failure in children with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective study. Gastroenterology 1993, 105, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selbuz, S.; Kansu, A.; Berberoglu, M.; Siklar, Z.; Kuloglu, Z. Nutritional status and body composition in children with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective, controlled, and longitudinal study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiountsioura, M.; Wong, J.E.; Upton, J.; McIntyre, K.; Dimakou, D.; Buchanan, E.; Cardigan, T.; Flynn, D.; Bishop, J.; Russell, R.K.; et al. Detailed assessment of nutritional status and eating patterns in children with gastrointestinal diseases attending an outpatients clinic and contemporary healthy controls. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, H.M.; Mohamed, M.S.; Alahmed, F.A.; Mohamed, A.M. Linear Growth Impairment in Patients with Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cureus 2022, 14, e26562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska-Seredyńska, K.; Akutko, K.; Umlawska, W.; Smieszniak, B.; Seredynski, R.; Stawarski, A.; Pytrus, T.; Iwanczak, B. Nutritional status of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel diseases is related to disease duration and clinical picture at diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, S.; Trivic, I.; Pavic, A.M.; Niseteo, T.; Kolacek, S.; Hojsak, I. Nutritional status and food intake in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis significantly differs from healthy controls. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkstetter, K.J.; Ullrich, J.; Schatz, S.B.; Prell, C.; Koletzko, B.; Koletzko, S. Lean body mass, physical activity and quality of life in paediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease and in healthy controls. J. Crohns. Colitis 2012, 6, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Kern, I.; Rothe, U.; Schoffer, O.; Weidner, J.; Richter, T.; Laass, M.W.; Kugler, J.; Manuwald, U. Growth development of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease in the period 2000–2014 based on data of the Saxon pediatric IBD registry: A population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, C.; Paerregaard, A.; Munkholm, P.; Faerk, J.; Lange, A.; Andersen, J.; Jakobsen, M.; Kramer, I.; Czernia-Mazurkiewicz, J.; Wewer, V. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: Increasing incidence, decreasing surgery rate, and compromised nutritional status: A prospective population-based cohort study 2007–2009. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 2541–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.J.; Green, Z.; Young, A.; Borca, F.; Coelho, T.; Batra, A.; Afzal, N.A.; Ennis, S.; Johnson, M.J.; Beattie, R.M. Growth failure is rare in a contemporary cohort of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinawi, F.; Assa, A.; Almagor, T.; Ziv-Baran, T.; Shamir, R. Prevalence and Predictors of Growth Impairment and Short Stature in Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion 2020, 101, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mouzan, M.; Alahmadi, N.; ALSaleeem, K.A.; Assiri, A.; AlSaleem, B.; Al Sarkhy, A. Prevalence of nutritional disorders in Saudi children with inflammatory bowel disease based on the national growth reference. Arab. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 21, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więch, P.; Binkowska-Bury, M.; Korczowski, B. Body composition as an indicator of the nutritional status in children with newly diagnosed ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease—A prospective study. Prz. Gastroenterol. 2017, 12, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Escher, J.C.; Shuman, M.J.; Forbes, P.W.; Delemarre, L.C.; Harr, B.W.; Kruijer, M.; Moret, M.; Allende-Richter, S.; Grand, R.J. Final adult height of children with inflammatory bowel disease is predicted by parental height and patient minimum height Z-score. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1669–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciuto, A.; Mack, D.R.; Huynh, H.Q.; Jacobson, K.; Otley, A.R.; deBruyn, J.; El-Matary, W.; Deslandres, C.; Sherlock, M.E.; Critch, J.N.; et al. Diagnostic Delay Is Associated With Complicated Disease and Growth Impairment in Paediatric Crohn’s Disease. J. Crohns. Colitis 2021, 15, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusseini, N.; Alsinan, N.; Almutahhar, S.; Khader, M.; Tamimi, R.; Elsarrag, M.I.; Warar, R.; Alnasser, S.; Ramadan, M.; Omair, A.; et al. Dietary trends and obesity in Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1326418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Definition | Assessment Methods |

|---|---|

| Growth impairment and growth failure [15,24] | |

| Growth impairment: A broad term describing any deviation from expected growth patterns, including slowed growth velocity or downward crossing of height percentiles, but not necessarily meeting criteria for short stature. Growth failure: A more severe form of impaired growth, typically defined as a height-for-age z-score significantly below expected (often <−2 SD) and/or a marked reduction in growth velocity compared with predicted or pre-illness growth. | Height-for-age z-score; growth velocity (cm/year); downward crossing of ≥2 major percentiles; comparison with mid-parental target height; serial growth measurements over time |

| Nutritional status: malnutrition [1,25] | |

| Malnutrition as deficiency, excess, or imbalance in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients | It is typically assessed using anthropometric measures (e.g., BMI z-score), and it is now recommended to complement these with body composition evaluation, particularly lean mass assessment, to better identify compromised nutritional status. |

| Body composition [26] | |

| Body composition analysis divides the body into its main tissue compartments: fat mass and fat-free mass, also referred to as lean body mass (LBM). LBM includes all non-adipose tissues, while muscle mass specifically refers to skeletal muscle tissue. | MUAC and MAMC can provide limited insight into muscle mass or visceral adiposity. More advanced techniques, including BIA, DXA, CT, MRI, and ultrasound, provide increasing levels of accuracy for estimating fat mass, fat-free mass, muscle mass, and visceral adiposity. |

| First Author, Year (Ref) | Country | Study Design | Study Population (n/Age/Disease Duration/Medication/Severity) | Nutritional Status Relevant Outcome | Method to Assess Nutritional Status Outcome | Control/Reference Group Used | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhou et al., 2024 [36] | Germany | Retrospective, population-based cohort study | N = 130 UC patients out of 421 patients with childhood onset IBD; no specific data on age and severity for the UC group; treatment-naïve at baseline. | Growth impairment | Weight and height z-scores were measured. Z-score < −1 is defined as growth failure and <−2 as short stature. The weight and height scores at diagnosis were converted to percentiles. | General German pediatric population (KiGGS 2003–2006) | UC patients had significantly lower weight at diagnosis (76% < P50, p = 0.001) versus the general population. Growth failure was observed in about 30% of the males and 36% of the females, and short stature was observed in 6% of the males and 16% of the females. Statistically significant difference was not reported between UC and general population. There was no significant difference in height percentiles and z-scores between UC patients and the general population. |

| Pawłowska-Seredyńska et al., 2023 [33] | Poland | Cross-sectional study | N = 29 UC patients out of 70 children with IBD were measured within 3 months from diagnosis; mean age 12.7 ± 2.9 years; most patients (59%) were treatment-naïve, and 65% were in remission or had mild disease activity. | Growth impairment, lean body mass and malnutrition (undernutrition, overnutrition and obesity) | Growth failure was defined as a height z-score < −1.64 and stunting as a height z-score < −2. Underweight was defined as a BMI z-score ≤ −2, overweight as a BMI z-score > 1 and ≤2, and obesity as a BMI z-score > 2. Lean body mass deficiency was defined as MUAC z-score < −2. | Reference population based on a group of healthy children without congenital or developmental disorders | Growth failure and stunting were reported in 6.9% and 3.4% of the UC patients. Underweight, overweight and obesity were observed in 6.9%, 6.9% and 3.5%, respectively, while lean body mass deficiency was present in 3% of the patients. Compared to the reference standard, the BMI z-score was significantly lower (−0.55 ± 0.99). |

| Isa et al., 2022 [32] | Bahrain | Retrospective, cross-sectional study | N = 41 UC patients out of 88 patients diagnosed with pediatric IBD; mean age at diagnosis was 10.7 ± 3.8 years for the total IBD population; median disease duration was 4.3 years for the total IBD population; Azathioprine, prednisolone and mesalamine therapy were used in most IBD patients (no data for UC); no data on disease severity. | Growth impairment | Growth impairment (stunting) and severe stunting were defined as height z-score < −2 and <−3, respectively. | WHO reference population | Stunting was observed in 19% patients with UC. Severe stunting was observed in 46.7% of the stunted patients in the total IBD population—no UC-specific data |

| Ashton et al., 2021 [38] | United Kingdom | Retrospective longitudinal study with follow-up up to 5 years | N = 157 UC patients out of 490 IBD patients; mean age 13.0 years at diagnosis; no further data on treatment or disease severity. | Growth impairment and malnutrition (undernutrition) | Stunting was defined as height-SDS < −2 and malnutrition was defined as weight-SDS < −2 | WHO reference population | No significant difference in malnutrition rates at diagnosis between the UC group and reference population (2.6% vs. 2.5%). The percentage of stunted patients (1.1%) did not differ from healthy population at diagnosis, 1 year, 2 years and 5 years follow-up. |

| Assa et al., 2021 [28] | Israel | Retrospective cohort study | N = 676 UC patients out of 2229 patients with childhood onset IBD; mean age 21.4 ± 3.3 of final height/weight measurement, 266 (37%) of all UC patients were diagnosed during their growth potential years (age at diagnosis <16 years for males; <14 years for females); mean disease duration 6.3 years; no further data on medication or disease severity | Growth impairment | Short stature was defined as an adult height z-score < −2. Final adult height and anthropometric z-scores (height, weight, BMI) measurements | Healthy controls N = 1252 with a mean age of 21.3 ± 3.3 years matched by socioeconomic status, sex, and year of birth | There was no difference in short stature rates between UC patients and controls (2.2% vs. 3.9%, p = 0.55) No difference in final height was noted between UC patients and controls. UC patients had lower BMI z-score at adulthood compared to controls (males: 0.23 ± 1.25 vs. 0.5 ± 1.38, p = 0.005; females: 0.07 ± 1.27 vs. 0.34 ± 1.38, p = 0.001). Females had lower weight z-score compared to controls (0.09 ± 1.29 vs. 0.21 ± 1.39, p = 0.04) |

| Rinawi et al., 2020 [39] | Israel | Retrospective longitudinal study providing data at diagnosis and in adulthood (18 years) | N = 125 UC patients out of 291 children with IBD; median age of diagnosis 13.5 years; 34% did not receive steroids during follow-up; no data on disease duration and severity | Growth impairment | Growth impairment defined as height z-score < –1. Growth failure at as height z-score ≤ –2 | Healthy controls, N = 125, matched 1:1 by gender and age | No significant difference in prevalence of growth impairment at diagnosis between UC and controls (25.4% vs. 16.9%, p = 0.452). Growth failure at diagnosis was also not significantly different (7.2% vs. 3.2%, p = 0.358). The mean final adult height was significantly lower among males who were diagnosed prior to final stage of puberty compared with those who were diagnosed post-final stage of puberty |

| Selbuz et al., 2020 [30] | Turkey | Prospective study with a one-year follow-up | N = 22 UC out of 36 children with IBD; most patients were in remission and were treated with aminosalicylates; no data on disease duration. | Growth impairment, malnutrition (undernutrition) and body composition | Growth failure was defined as height z-score < −2, undernutrition as weight z-score < −2, severe malnutrition as BMI z score < −2. Body composition was assessed using BIA, MUAC and TSF | Healthy control, N = 43, matched by gender and age | Growth failure was observed in 9.1% of UC patients at the end of the study. At baseline, 4.5% of UC patients were undernourished, and 13.6% of these patients were severely malnourished. By the end of the study, 4.5% remained undernourished, and 9.1% were severely malnourished. Compared to matched controls, changes in anthropometrics and body composition parameters during 1-year follow-up did not differ significantly, except for an increase in the triceps skinfold thickness z score. Both FM and FFM significantly improved significantly over time |

| El Mouzan et al., 2020 [40] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study | N= 119 UC patients out of 374 children and adolescents with pediatric IBD; mean age at diagnosis was 9.1 SD years (no data for UC patients); extensive colitis was the commonest extent at diagnosis (58%); no data on medication or disease duration and severity | Growth impairment and malnutrition (undernutrition and overnutrition) | Short stature was defined as Height z-score < −2 Thinness (underweight) was defined as BMI z-score < −2 Overweight (including obesity) was defined as BMI z-score > 1 | Saudi National Growth Reference and WHO reference population | Based on the national growth reference, the prevalence of thinness, overweight, and short stature in the UC group was 8% (p = 0.005), 20% (p = 0.004), and 12% (p = 0.91), respectively. Using the WHO reference, the prevalence of thinness, overweight, and short stature in the UC group was significantly higher at 24%, 20%, and 21%, respectively. |

| Sila et al., 2019 [34] | Croatia | Cross-sectional study | N = 40 UC patients out of 89 newly diagnosed children with IBD; mean age 14.0 ± 3.7 years; most patients (59%) had not received any medication, and 65% were in remission or had mild disease activity. | Malnutrition (undernutrition and overnutrition) and body composition | Mild malnutrition was defined as a BMI z-score between −1 and −2, while moderate and severe malnutrition were defined as a BMI z-score ≤ −2. Overweight was defined as BMI z-score ≥ 1, and obesity as ≥2 Body composition was assessed using BIA, MUAC, TSF, SSF and HGS. | Healthy control N = 159 with the mean age 14.7 years | Compared to healthy controls, significantly lower lean body mass for age z-scores were found. TSF, SSF, MUAC, and body fat percentages did not differ significantly from healthy controls. At diagnosis, 25% of UC patients were undernourished, including 10% moderately to severely malnourished, compared to 1.9% in controls. Overweight was seen in 17.5% of UC patients vs. 21.4% in controls, with no UC patients classified as obese, compared to 8.2% of controls. |

| Więch et al., 2017 [41] | Poland | Prospective study with a one-year follow-up | N = 16 newly diagnosed UC patients out of 59 IBD patients of which n = 9 were assessed again 1 year after their UC diagnosis; mean age 13.5 years; medication not specified; most patients had mild to moderate disease. | Body composition | Body composition, including FM, FFM, BCM, MM, TBW, was assessed using BIA. | Healthy controls N = 16 matched by age and sex | Compared to healthy controls, UC patients did not differ significantly in FM, FFM, MM, BCM, and TBM. After one year, all the selected components of body composition were increased significantly, except for the FM. |

| Tsiountsioura et al., 2014 [31] | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional study | N = 27 pediatric UC patients out of 168 patients from outpatient gastroenterology clinics; median age 12.2 years; disease duration and medication not detailed; 63% had inactive disease. | Growth impairment, malnutrition (undernutrition and overnutrition) and body composition | Short stature was defined as height z-score < −2. Participant with a BMI z-score < −2 were classified as thin and with BMI z-score > 2 as obese. Body composition was assessed using BIA, TSF, and HGS. | Healthy controls N = 62, median age 9.8 years | No significant differences were found between UC patients and controls in the prevalence of short stature (3.7% vs. 4.9%), BMI z-scores (0.8 vs. 0.3), prevalence of thinness (0 vs.4.9) or prevalence of obesity (19% vs. 15%, respectively). Compared to controls, there was no significant difference in lean mass z-scores, fat mass z-scores, TSF z-scores and grip strength for height. |

| Werkstetter et al., 2012 [35] | Germany | Cross-sectional study | N = 12 UC patients out of 39 patients with IBD; median age at diagnosis 11.7 years; median disease duration 3.1 years; All the patients have used glucocorticoids at some point, most patients were treated with either aminosalicylates or azathiopirine; 66% were in remission. | Body composition and malnutrition | Height, weight, and BMI z-scores were measured. Body composition was assessed using BIA to measure the phase angle α as indicator of lean body mass. In addition, grip strength was measured. | Healthy controls N = 39 matched by age and sex | UC patients had significantly reduced phase angle α compared to controls. No differences between patients and healthy controls in height, weight, BMI, and hand grip strength. |

| Jakobsen et al., 2011 [37] | Denmark | Prospective cohort study with a median follow-up of 511 days (IQR 191–1053) | N = 62 UC out of 130 patients (<15 years) with IBD; Mean age at diagnosis was 12.4 years; medication used (in proportions of patients): 5-ASA (87.1%), corticosteroids (1.6%), Immunomodulators (33.9%), biological treatment (17.7%); no data on disease duration or severity. | Growth impairment and malnutrition (undernutrition) | Growth retardation was defined as height z-score < −2. Malnutrition was defined as BMI z-score < −2. | Healthy Danish pediatric reference population | No UC patients had weight or height z-score < −2, but 11.5% were considered malnourished at diagnosis (no follow-up results on growth and nutritional status available). |

| Lee et al., 2010 [42] | United States of America | Prospective cohort study with a mean follow-up of 2.3 SD years from the time of diagnosis | N = 84 UC patients out of 295 IBD patients; mean age at enrollment was 13.9 for the total IBD population (no data for UC); Corticosteroids, Immunosuppressive therapy, Biologic therapy, Nutrition therapy were used in most patients (no data for UC); 73.8% of UC patients had extensive involvement at enrollment; no further data on disease duration or severity | Growth impairment | Growth impairment was defined as height for age z-score < −1.64 in more than one measurement since diagnosis. | National Center for Health Statistics general population reference | Growth impairment was observed in 12% of patients with UC. Other outcomes were outside the scope of this review. |

| Motil et al., 1993 [29] | United States of America | Prospective study with a short-term follow-up of one year and a long-term follow-up of up to three years. | N = 35 UC out of 70 children with IBD; mean age 12.0 years; Seventy-four percent received sulfasalazine and 34% corticosteroids as treatment. Disease duration was less than one year in 49% of the patients. Most patients were in remission, experiencing no abdominal pain and having normal bowel movements. | Growth impairment | Growth failure was defined as height and weight z-scores < −1.64, height less than 95% of the expected value at the 50th percentile for age, or weight less than 90% of the expected value at the 50th percentile for age or height. Additionally, growth failure included height velocity less than 4 cm per year for males under 15 years and females under 13 years, as well as weight velocity less than 1.0 kg per year for males under 15 years and females under 13 years. | National growth reference | Growth failure was observed in 23% of children with UC based on height-for-age measurements, in 9% based on height Z scores, in 31% based on weight-for-age, in 14% based on weight-for-height, and in 6% based on weight Z scores. Growth failure assessed by height and weight velocity was identified in 16% and 6% of patients, respectively. No significant differences in height or weight Z scores were found between baseline and long-term follow-up. |

| Domain | Cross-Sectional Studies (n = 5) | Cohort Studies (n = 10) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population & setting | Mostly adequate | Mostly adequate | Limited UC-specific detail |

| UC definition & outcome measurement | Adequate | Adequate | Outcome measurement: the wide range of tools and cut-offs used across studies limits comparability and hampers synthesis of the evidence |

| Confounding identified and addressed | Rarely | Inconsistently | Limited identification of potential confounders, including disease activity, treatment exposure, pubertal stage, age, and other patient and clinical characteristics |

| Follow-up and completeness | Not applicable | Variable | Incomplete reporting of follow-up duration and loss to follow-up |

| Statistical analysis | Generally appropriate | Generally appropriate | Limited UC-specific analyses in mixed IBD cohorts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarbagili-Shabat, C.; Timmer, F.; Morogianni, K.; de Vries, R.; de Meij, T.; van der Kruk, N.; Verstoep, L.; Wierdsma, N.; Van Limbergen, J. Nutritional Status, Body Composition and Growth in Paediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2026, 18, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010169

Sarbagili-Shabat C, Timmer F, Morogianni K, de Vries R, de Meij T, van der Kruk N, Verstoep L, Wierdsma N, Van Limbergen J. Nutritional Status, Body Composition and Growth in Paediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarbagili-Shabat, Chen, Floor Timmer, Konstantina Morogianni, Ralph de Vries, Tim de Meij, Nikki van der Kruk, Lana Verstoep, Nicolette Wierdsma, and Johan Van Limbergen. 2026. "Nutritional Status, Body Composition and Growth in Paediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010169

APA StyleSarbagili-Shabat, C., Timmer, F., Morogianni, K., de Vries, R., de Meij, T., van der Kruk, N., Verstoep, L., Wierdsma, N., & Van Limbergen, J. (2026). Nutritional Status, Body Composition and Growth in Paediatric-Onset Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 18(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010169