Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Blood Cell Profiles and the Molecular Composition of Platelet-Rich Plasma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population—Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Blood Sampling

2.3. PRP Processing

2.4. Hematological Assessment

2.5. Protein Quantification

2.6. Assessment of Dietary Patterns

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Hematological Parameters in Whole Blood and LP-PRP

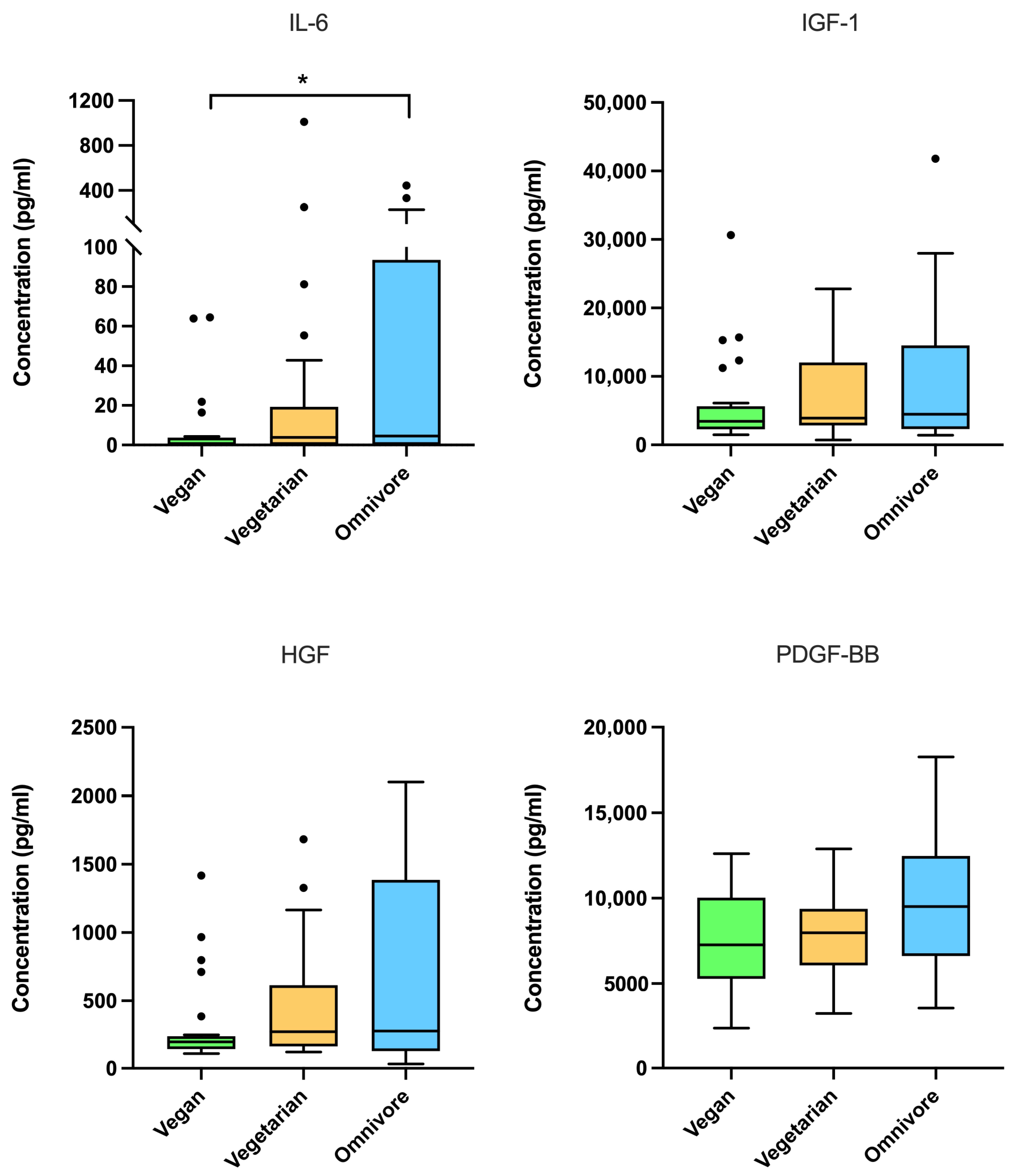

3.3. Protein Concentrations in LP-PRP Among Dietary Patterns

3.4. Platelet–Protein Correlations Between Dietary Patterns

3.5. Correlations of Dietary Variables and Hematological Parameters in Whole Blood

3.6. Correlations of Dietary Variables and Hematological Parameters in LP-PRP

3.7. Correlations of Dietary Variables and Protein Concentrations in LP-PRP

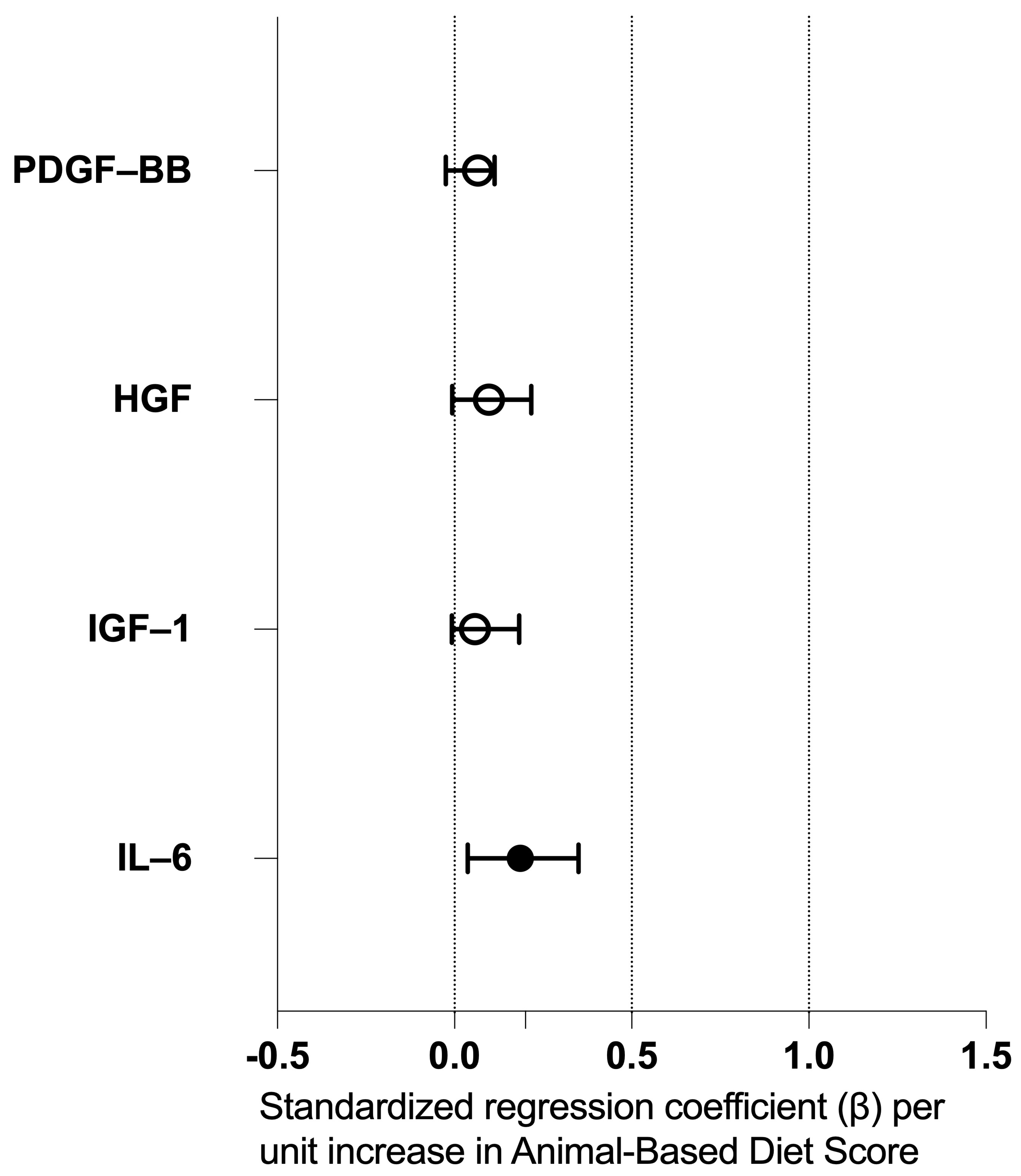

3.8. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | American College of Rheumatology |

| ADAMTS | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs |

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic acid |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DMARD | Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug |

| DMOAD | Disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ESSKA | European Society of Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy |

| FFQ | Food-frequency questionnaire |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LP-PRP | Leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma |

| LR-PRP | Leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma |

| mL | milliliter |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| nL | nanoliter |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| OA | Osteoarthritis |

| OARSI | Osteoarthritis Research Society International |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| pg | Picogram |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Everts, P.; Onishi, K.; Jayaram, P.; Lana, J.F.; Mautner, K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: New Performance Understandings and Therapeutic Considerations in 2020. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, J.W.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Houck, D.A.; Goodrich, J.A.; Dragoo, J.L.; McCarty, E.C. Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Hyaluronic Acid for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.V.; Saadat, P.; Bobos, P.; Iskander, S.M.; Bodmer, N.S.; Rudnicki, M.; Dan Kiyomoto, H.; Montezuma, T.; Almeida, M.O.; Bansal, R.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of intra-articular interventions for knee and hip osteoarthritis based on large randomized trials: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2025, 33, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensa, A.; Sangiorgio, A.; Boffa, A.; Salerno, M.; Moraca, G.; Filardo, G. Corticosteroid injections for knee osteoarthritis offer clinical benefits similar to hyaluronic acid and lower than platelet-rich plasma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EFORT Open Rev. 2024, 9, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazendam, A.; Ekhtiari, S.; Bozzo, A.; Phillips, M.; Bhandari, M. Intra-articular saline injection is as effective as corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid for hip osteoarthritis pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, A.J.; Gray, B.; Wallis, J.A.; Taylor, N.F.; Kemp, J.L.; Hunter, D.J.; Barton, C.J. Recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2023, 31, 1280–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanson, J.R.; Guyton, M.K.; Oliver, D.L.; Hire, J.M.; Topolski, R.L.; Zumbrun, S.D.; McPherson, J.C.; Bojescul, J.A. Gender and age differences in growth factor concentrations from platelet-rich plasma in adults. Mil. Med. 2014, 179, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Bulsara, M.K.; McCrory, P.R.; Richardson, M.D.; Zheng, M.H. Analysis of Platelet-Rich Plasma Extraction: Variations in Platelet and Blood Components Between 4 Common Commercial Kits. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2017, 5, 2325967116675272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karina; Wahyuningsih, K.A.; Sobariah, S.; Rosliana, I.; Rosadi, I.; Widyastuti, T.; Afini, I.; Wanandi, S.I.; Soewondo, P.; Wibowo, H.; et al. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma from diabetic donors shows increased platelet vascular endothelial growth factor release. Stem Cell Investig. 2019, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jeyaraman, M.; Maffulli, N. Common Medications Which Should Be Stopped Prior to Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachito, D.V.; Bagattini, A.M.; de Almeida, A.M.; Mendrone-Junior, A.; Riera, R. Technical Procedures for Preparation and Administration of Platelet-Rich Plasma and Related Products: A Scoping Review. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 598816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahla, J.; Cinque, M.E.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Mannava, S.; Geeslin, A.G.; Murray, I.R.; Dornan, G.J.; Muschler, G.F.; LaPrade, R.F. A Call for Standardization in Platelet-Rich Plasma Preparation Protocols and Composition Reporting: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Orthopaedic Literature. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2017, 99, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaez, A.; Lassale, C.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Ros, E.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Castaner, O.; Pinto, X.; Vazquez-Ruiz, Z.; Sorli, J.V.; Salas-Salvado, J.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Maintained Platelet Count within a Healthy Range and Decreased Thrombocytopenia-Related Mortality Risk: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelman, L.; Egea Rodrigues, C.; Aleksandrova, K. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laevski, A.M.; Doucet, M.R.; Doucet, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.A.; Pineau, P.E.; Hébert, M.P.A.; Doiron, J.A.; Roy, P.; Mbarik, M.; Matthew, A.J.; et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids modulate the production of platelet-derived microvesicles in an in vivo inflammatory arthritis model. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 2221–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.Y.N.; Key, T.J.; Gaitskell, K.; Green, T.J.; Guo, W.; Sanders, T.A.; Bradbury, K.E. Hematological parameters and prevalence of anemia in white and British Indian vegetarians and nonvegetarians in the UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, G.P.; Wolffram, S.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Gibbins, J.M. Ingestion of quercetin inhibits platelet aggregation and essential components of the collagen-stimulated platelet activation pathway in humans. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 2, 2138–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthley, M.I.; Prabhu, A.; De Sciscio, P.; Schultz, C.; Sanders, P.; Willoughby, S.R. Detrimental effects of energy drink consumption on platelet and endothelial function. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernaez, A.; Lassale, C.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Babio, N.; Ros, E.; Castaner, O.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Pinto, X.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Corella, D.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and White Blood Cell Count-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foods 2021, 10, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegertjes, R.; van de Loo, F.A.; Blaney Davidson, E.N. A roadmap to target interleukin-6 in osteoarthritis. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 2681–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungunsukh, O.; McCart, E.A.; Day, R.M. Hepatocyte Growth Factor Isoforms in Tissue Repair, Cancer, and Fibrotic Remodeling. Biomedicines 2014, 2, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, L.; Lyu, K.; Lu, J.; Long, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Li, S. A Promising Candidate in Tendon Healing Events-PDGF-BB. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Xu, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; Liang, Y.; Duan, L. Insulin-like growth factor-1 in articular cartilage repair for osteoarthritis treatment. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano-Núñez, A.; Cornelis, F.M.F.; De Roover, A.; Sermon, A.; Cailotto, F.; Lories, R.J.; Monteagudo, S. IGF1 drives Wnt-induced joint damage and is a potential therapeutic target for osteoarthritis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.J.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-Y.; Noh, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, J.A.; Jeon, Y.S.; Shin, H.; Ryu, D.J. Hepatocyte Growth Factor-Mediated Chondrocyte Proliferation Induced by Adipose-Derived MSCs from Osteoarthritis Patients and Its Synergistic Enhancement by Hyaluronic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platzer, H.; Bork, A.; Wellbrock, M.; Horsch, A.; Pourbozorg, G.; Gantz, S.; Sorbi, R.; Hagmann, S.; Bangert, Y.; Moradi, B. The Time of Blood Collection Does Not Alter the Composition of Leucocyte-Poor Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Quantitative Analysis of Platelets and Key Regenerative Proteins. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthrex. ACP® Double-Syringe System—Simple and efficient preparation of PRP. Patent, 2023. Available online: https://discover.arthrex.de/acp-doppelspritze (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Burnouf, T.; Strunk, D.; Koh, M.B.; Schallmoser, K. Human platelet lysate: Replacing fetal bovine serum as a gold standard for human cell propagation? Biomaterials 2016, 76, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftenberger, M.; Heuer, T.; Heidemann, C.; Kube, F.; Krems, C.; Mensink, G.B. Relative validation of a food frequency questionnaire for national health and nutrition monitoring. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craddock, J.C.; Neale, E.P.; Peoples, G.E.; Probst, Y.C. Vegetarian-Based Dietary Patterns and their Relation with Inflammatory and Immune Biomarkers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, M.A.; Kowarschik, S.; Herter, J.; Huber, R. Whole blood count data and hematological parameters in US vegetarians: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2025, 64, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.J. The influence of diet and nutrients on platelet function. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2014, 40, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Schwartz, B. The relationship between nutrition and the immune system. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1082500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Moscona, A.; Myndzar, K.; Luttrell-Williams, E.; Vanegas, S.; Jay, M.R.; Calderon, K.; Berger, J.S.; Heffron, S.P. More frequent olive oil intake is associated with reduced platelet activation in obesity. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3322–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platzer, H.; Bork, A.; Wellbrock, M.; Pourbozorg, G.; Gantz, S.; Sorbi, R.; Mayakrishnan, R.; Hagmann, S.; Bangert, Y.; Moradi, B. Association Between Body Mass Index and the Composition of Leucocyte-Poor Platelet-Rich Plasma: Implications for Personalized Approaches in Musculoskeletal Medicine. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, C.N.; Aggrey, A.A.; Chapman, L.M.; Modjeski, K.L. Emerging roles for platelets as immune and inflammatory cells. Blood 2014, 123, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggrey, A.A.; Srivastava, K.; Ture, S.; Field, D.J.; Morrell, C.N. Platelet induction of the acute-phase response is protective in murine experimental cerebral malaria. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 4685–4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Rippe, R.A.; Niemela, O.; Brittenham, G.; Tsukamoto, H. Role of iron in NF-kappa B activation and cytokine gene expression by rat hepatic macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, G1355–G1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Lin, M.; Ohata, M.; Giulivi, C.; French, S.W.; Brittenham, G. Iron primes hepatic macrophages for NF-kappaB activation in alcoholic liver injury. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, G1240–G1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.C.; Tsai, S.F.; Chou, H.W.; Tsai, M.J.; Hsu, P.L.; Kuo, Y.M. Dietary fatty acids differentially affect secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human THP-1 monocytes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, H.; Kubon, K.D.; Diederichs, S.; Bork, A.; Gantz, S.; Schiltenwolf, M.; Renkawitz, T.; Bangert, Y. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): Compositional analysis with different dietary habits and timing of blood sampling. Orthopadie 2023, 52, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 75) | Dietary Pattern | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegan (n = 25) | Vegetarian (n = 25) | Omnivore (n = 25) | |||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.850 | ||||

| Female | 42 (56%) | 14 (56%) | 15 (60%) | 13 (52%) | |

| Male | 33 (44%) | 11 (44%) | 10 (40%) | 12 (48%) | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD; IQR | 25.92 ± 4.17; 6.00 | 26.60 ± 4.52; 7.00 | 25.72 ± 3.62; 6.00 | 25.44 ± 4.39; 7.00 | 0.407 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD; IQR | 22.56 ± 3.17; 3.94 | 23.06 ± 3.52; 3.93 | 22.86 ± 3.37; 4.83 | 21.76 ± 2.51; 2.41 | 0.414 |

| Sport activity (hours per week), mean ± SD; IQR | 5.75 ± 3.68; 5.25 | 6.07 ± 3.17; 4.50 | 6.62 ± 4.65; 5.75 | 4.43 ± 2.70; 5.38 | 0.216 |

| Dietary Variables * | |||||

| (Processed) meat; median; IQR | 1; 2 | 1; 0 | 1; 0 | 3.5; 1 | <0.001 |

| Non-meat animal-derived foods; median; IQR | 4; 4 | 1; 0 | 4; 1 | 5; 1 | <0.001 |

| Fish; median; IQR | 1; 1 | 1; 0 | 1; 0 | 2; 1 | <0.001 |

| Fruits and vegetables; median; IQR | 6; 1 | 6; 1 | 6; 1 | 5; 2 | <0.001 |

| Animal-Based Diet Score median; IQR | 5; 6 | 2; 0 | 5; 1 | 8; 2 | <0.001 |

| Dietary Pattern | p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivore | ||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Whole blood | Platelets (/nL) | 225.56 | 52.86 | 241.16 | 59.33 | 231.96 | 55.12 | 0.646 |

| Erythrocytes (×103/nL) | 4.62 | 0.39 | 4.72 | 0.46 | 4.77 | 0.43 | 0.673 | |

| Leukocytes (/nL) | 5.35 | 1.49 | 6.43 | 1.93 | 5.78 | 1.11 | 0.024 | |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 30.38 | 6.43 | 30.31 | 7.36 | 33.80 | 5.91 | 0.039 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.10 | 1.36 | 5.81 | 1.30 | 5.56 | 1.53 | 0.432 | |

| Basophils (%) | 0.72 | 0.24 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.043 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 2.44 | 2.03 | 2.76 | 2.55 | 2.94 | 1.72 | 0.148 | |

| Neutrophils (%) | 58.13 | 6.96 | 58.50 | 8.49 | 54.70 | 7.39 | 0.094 | |

| LP-PRP | Platelets (/nL) | 457.68 | 119.17 | 493.92 | 131.32 | 496.76 | 147.39 | 0.497 |

| Erythrocytes (×103/nL) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.577 | |

| Leukocytes (/nL) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.807 | |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 28.96 | 23.63 | 29.74 | 22.50 | 27.17 | 22.43 | 0.906 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 11.84 | 6.21 | 10.63 | 5.95 | 10.18 | 8.14 | 0.537 | |

| Basophils (%) | 1.39 | 2.20 | 1.02 | 2.57 | 0.84 | 1.62 | 0.557 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 5.80 | 3.68 | 6.05 | 3.92 | 7.17 | 3.41 | 0.324 | |

| Neutrophils (%) | 48.38 | 19.65 | 48.66 | 20.35 | 48.72 | 16.87 | 0.955 | |

| PRP-to-whole blood platelet ratio | 2.05 | 0.34 | 2.06 | 0.33 | 2.14 | 0.39 | 0.846 | |

| Platelets Whole Blood 1 | Platelets PRP 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivore | Vegan | Vegetarian | Omnivore | ||

| IL-6 | ρ p-Value | 0.288 0.162 | 0.150 0.474 | 0.199 0.339 | 0.116 0.582 | 0.176 0.401 | 0.483 * 0.014 |

| IGF-1 | ρ p-Value | 0.263 0.204 | 0.078 0.712 | 0.229 0.272 | 0.098 0.641 | 0.020 0.924 | 0.412 * 0.041 |

| HGF | ρ p-Value | 0.380 0.061 | 0.135 0.538 | 0.031 0.884 | 0.258 0.214 | 0.100 0.650 | 0.416 * 0.039 |

| PDGF-BB | ρ p-Value | 0.485 * 0.014 | 0.378 0.068 | 0.355 0.082 | 0.544 * 0.005 | 0.471 * 0.020 | 0.624 * <0.001 |

| Dietary Variables 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Processed) Meat | Non-Meat Animal-Derived Foods | Fish | Fruits and Vegetables | Animal-Based Diet Score | ||

| Platelets (/nL) | ρ p-Value | −0.022 0.856 | 0.057 0.637 | −0.019 0.878 | −0.099 0.400 | 0.001 0.998 |

| Erythrocytes (×103/nL) | ρ p-Value | 0.134 0.273 | 0.195 0.104 | 0.146 0.232 | −0.187 0.111 | 0.141 0.251 |

| Leukocytes (/nL) | ρ p-Value | 0.150 0.218 | 0.255 * 0.032 | 0.219 0.071 | −0.064 0.586 | 0.226 0.064 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | ρ p-Value | −0.033 0.787 | 0.044 0.715 | 0.073 0.551 | 0.019 0.087 | 0.020 0.869 |

| Monocytes (%) | ρ p-Value | −0.123 0.315 | −0.148 0.219 | −0.167 0.170 | −0.146 0.215 | −0.181 0.139 |

| Basophils (%) | ρ p-Value | −0.047 0.703 | −0.236 * 0.048 | −0.173 0.154 | 0.255 0.054 | −0.151 0.218 |

| Eosinophils (%) | ρ p-Value | 0.200 0.099 | 0.143 0.234 | 0.084 0.495 | −0.212 0.070 | −0.181 0.140 |

| Neutrophils (%) | ρ p-Value | −0.042 0.731 | −0.095 0.433 | −0.103 0.402 | 0.142 0.228 | −0.085 0.490 |

| Dietary Variables 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Processed) Meat | Non-Meat Animal-Derived Foods | Fish | Fruits and Vegetables | Animal-Based Diet Score | ||

| IL-6 | ρ p-Value | 0.242 * 0.045 | 0.407 * <0.001 | 0.074 0.544 | −0.078 0.509 | 0.356 * 0.003 |

| IGF-1 | ρ p-Value | 0.093 0.448 | 0.191 0.111 | 0.053 0.663 | −0.043 0.718 | 0.161 0.188 |

| PDGF-BB | ρ p-Value | 0.261 * 0.032 | 0.174 0.150 | 0.181 0.140 | −0.340 * 0.003 | 0.232 0.059 |

| HGF | ρ p-Value | 0.023 0.851 | 0.227 0.061 | −0.029 0.815 | −0.101 0.399 | 0.124 0.323 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Platzer, H.; Bork, A.; Gantz, S.; Khamees, B.; Simon, M.J.K.; Hagmann, S.; Bangert, Y.; Moradi, B. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Blood Cell Profiles and the Molecular Composition of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Nutrients 2026, 18, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010163

Platzer H, Bork A, Gantz S, Khamees B, Simon MJK, Hagmann S, Bangert Y, Moradi B. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Blood Cell Profiles and the Molecular Composition of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010163

Chicago/Turabian StylePlatzer, Hadrian, Alena Bork, Simone Gantz, Baraa Khamees, Maciej J. K. Simon, Sébastien Hagmann, Yannic Bangert, and Babak Moradi. 2026. "Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Blood Cell Profiles and the Molecular Composition of Platelet-Rich Plasma" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010163

APA StylePlatzer, H., Bork, A., Gantz, S., Khamees, B., Simon, M. J. K., Hagmann, S., Bangert, Y., & Moradi, B. (2026). Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Blood Cell Profiles and the Molecular Composition of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Nutrients, 18(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010163