Development of a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Sweets and Appetizers in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Insights from Qatar

Abstract

1. Introduction

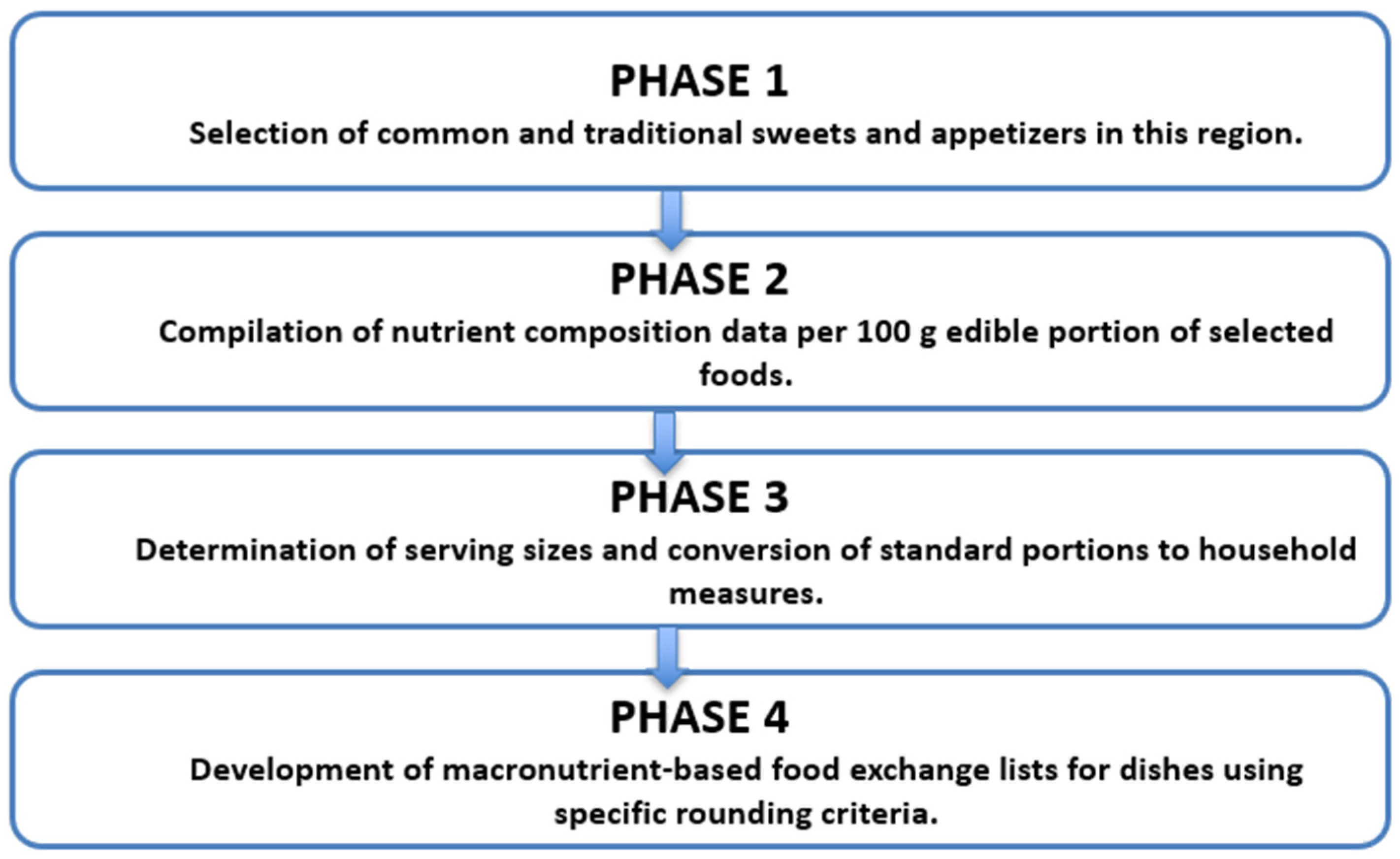

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Selection of the Dishes

- Frequently consumed in GCC and Qatar, either daily (e.g., breads, dips, appetizers) or during festive occasions such as Ramadan, Eid, weddings, and family gatherings (e.g., traditional sweets).

- Held cultural or traditional significance, forming part of GCC and Qatari heritage and social practices.

- Widely available in households, restaurants, or bakeries, ensuring accessibility across settings.

- Contributed substantially to carbohydrate, fat, or overall energy intake in the GCC and Qatari diet [17].

- Represented distinct preparation categories (e.g., fried sweets, puddings, bread-based items, savory appetizers).

- Items with highly variable recipes or limited regional consumption were excluded to ensure standardization feasibility.

- The selected dishes represent those with the greatest relevance for Medical Nutrition Therapy, due to their high contribution to carbohydrate, fat, or sugar intake, especially among individuals with diabetes and cardiometabolic risk.

2.2. Phase 2: Collection of Food Composition Data for Selected Dishes

Statistical Analysis

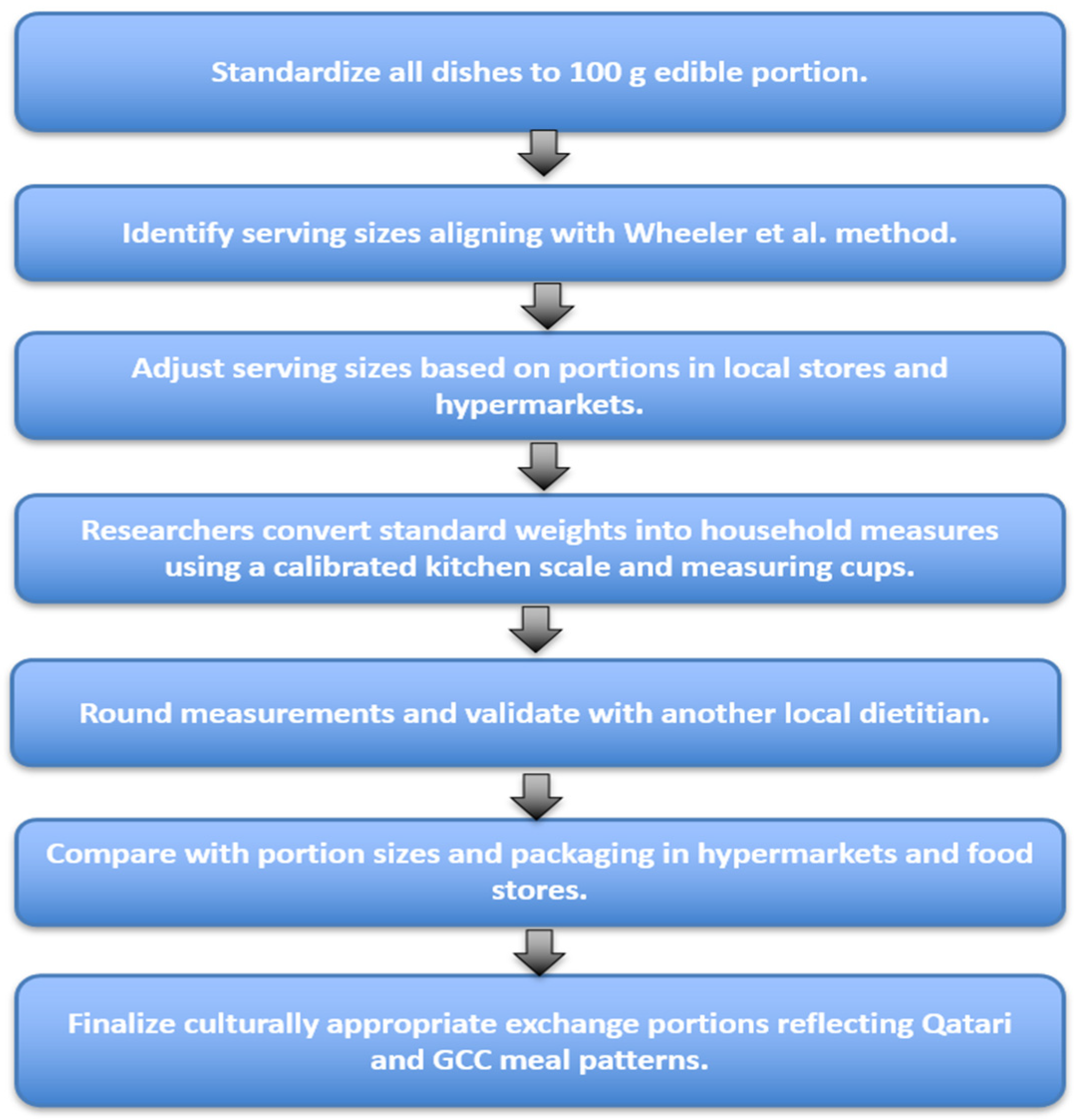

2.3. Phase 3: Determination of Serving Size

2.4. Phase 4: Fitting the Dishes in the Exchange List

- Carbohydrate exchange:

- Protein exchange:

- Fat exchange:

| Carbohydrate exchange: |

|

| Protein exchange (meat and substitutes): |

|

| Fat exchange: |

|

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural and Public-Health Significance of GCC Sweets and Appetizers

4.2. Macronutrient Findings and Clinical Implications

4.3. Comparison with International and Regional Culturally Adapted Exchange Systems

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Practical, Policy, and Future Work Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMFID | Eastern Mediterranean Food Information Database |

| MFM | Medium Fat Meat |

| LM | Lean Meat |

Appendix A

| Dish Name | Ingredients |

|---|---|

| SWEETS | |

| Balleleet | Vermicelli 100 g, Sugar (sucrose) 50 g, Oil (pure corn oil) 15 g, Dried cardamom (ground) 3 g (Elettaria sp.), Water 700 mL |

| Mahamer | Rice 200 g (1 1/4 cup), Sugar (sucrose) 216 g, Pure corn oil 10 g (1 tbsp), melted butter 8 g (1 tbsp), fennel seed 1 g (1/2 tsp), Water 5 cups. |

| Barinoish | Rice 60, Sugar 20, water 20 |

| Sago (Sagau) | Sago 50, sugar 33, hot water 10, rose water with saffron 2, powdered cardamom 2, Margarine 1, and Nuts 2 |

| Khabeese | Semolina 150 g, Sugar (sucrose) 80 g, butter 50 g, Cardamom (ground) 1 g, raisin 39 g, Water ½ cup |

| Khanfarooshe | Semolina 150 g (1 cup), Ground rice 95 g, Egg 118 g (2), Oil (pure corn oil) 70 g (1/3 cup), sugar (sucrose) 75 g, Cardamom (Elettaria sp.) 1 g, Baking soda 1 g, Water 1/4 cup |

| Hesso (Egg and watercress sweet) | Watercress seeds (2 tbsp, 20 g), 1 egg (51 g), corn oil (2 tbsp, 20 g), sugar (1/4 cup, 68 g), mixed spices (1 1/4 tsp, 2 g), water (2 1/2 cups) |

| Elbah | Eggs (2)102 g, whole milk, liquid (1 cup), ground cardamom (1/4 tsp), ground saffron (0.5 g), sugar (1/4 cup, 68 g) |

| Aigalee (cardamom cake) | Flour (wheat flour) 125 g, Egg 90 g, Sugar (sucrose) 80 g, Sesame seeds 10 g, Ghee (cow ghee) 20 g, Cardamom (Elettaria sp.) 3 g |

| Asseda (assedah) | Flour (wheat flour) 100 g, Ghee (cows’ ghee) 25 g, Sugar (sucrose) 75 g, Cardamom (ground) 3 g, Ginger (ground) 2 g, Water 350 ml |

| Luqemat/Awameh | All-purpose flour, bleached, enriched, pre-sifted (500 g), Corn oil, 100% pure (0.75 cup), Cornstarch (2 tbsp), salt, table (0.13 tsp), Sugar granulated (1 tbsp), water (0.25 cup), Yeast, baker’s, active, dry (1 tsp) |

| Muhalbiya (Rice pudding) | whole milk (11/4 cup, 275 g), sugar (1/8 cup, 33 g), rice flour (2 tbsp, 15 g) vanilla (4 drops) |

| Betheeth | Dates (1 cup), wheat flour (1/2 cup) roasted in dry pan (68 g), butter (1/4 cup, 50 g), ground cardamom (1 tsp) |

| Konafah na’ema bil jibn | Soaked cheese 360 g, Sugar syrup 250 g, Flour 240 g, Margarine 52 g, Pistachio 10 g, Sugar 12 g, Dried whey milk protein 4 g. Purchased—five brands sourced (1:1 ratio) |

| Qatayif bil jibn Maqli | Dough 325 g, (Flour 296 g, Sodium bicarbonate 9 g, Warm water 474 g, Liquid milk 250 g, Sugar 45 g, Fine semolina 165 g, Salt 2 g), White desalted cheese 150 g, Plant oil for frying, Sugar syrup (2:1) 25 g. |

| Qatayif bil jooz Maqli | Dough 325 g (Flour 296 g, Sodium bicarbonate 9 g, Warm water 474 g, Liquid milk 250 g, Sugar 45 g, Fine semolina 165 g, Salt 2 g), Filling 143 g (Walnut 270 g, Sugar 11 g, Cinnamon 4 g, Blossom water 24 g), Plant oil for frying, Sugar syrup (2:1) 46 g. |

| Qatayif bil jibn Mashwi | Dough 325 g (Flour 296 g, Sodium bicarbonate 9 g, Warm water 474 g, Liquid milk 250 g, Sugar 45 g, Fine semolina 165 g, Salt 2 g), White desalted cheese 150 g. |

| Qatayif bil jooz Mashwi | Dough 325 g (Flour 296 g, Sodium bicarbonate 9 g, Warm water 474 g, Liquid milk 250 g, Sugar 45 g, Fine semolina 165 g, Salt 2 g), Filling 143 g (Walnut 270 g, Sugar 11 g, Cinnamon 4 g, Blossom water 24 g). |

| Ma’amool ajwa bilsameed | Fine semolina 1000 g, Chopped dates 600 g, Butter 350 g, Milk 200 g, Corn oil 65 g, Sugar 35 g, Vegetable margarine 35 g, Crushed anise 25 g, Cinnamon 15 g, Mehlab 10 g, Fennel 10 g. Purchased—five brands sourced (1:1 ratio) |

| Ma’amool ajwa bil taheen | Dates 330 g, Flour 262 g, Butter 125 g, Milk 100 g, Sugar 47 g, Corn oil 30 g, Fennel 7 g, Crushed anise 7 g, Vanilla 5 g, Baking powder 3.5 g, Mistika 3 g, Cinnamon 0.5 g. Purchased—five brands sourced (1:1 ratio) |

| Mamool bil jooz | Fine semolina 188 g, Butter 62 g, Walnut 35 g, Milk 30 g, Sugar syrup 15 g, Corn oil 13 g, Sugar 7 g, Flower water 5 g, Mehlab 2 g, Crushed anise 2 g, Fennel 2 g. Purchased—five brands sourced (1:1 ratio) |

| Mamool bil fustok | Fine semolina 562 g, Butter 188 g, Crushed pistachio 150 g, Milk 100 g, Sugar syrup 60 g, Corn oil 37 g, Sugar 19 g, Flower water 5 g, Mehlab 4 g, Crushed anise 4 g, Fennel 4 g. Purchased—five brands sourced (1:1 ratio) |

| APPETIZERS AND PIES | |

| Motabbal bathijan bil tahina | Eggplant 490 g, Tahina 60 g, Lemon juice 65 g, Olive oil 15 g, Parsley 5 g, Salt 6 g, Garlic 2 g. |

| Hummus bil tahina | Dried chickpea 80 g (=173 g boiled chickpea), Lemon juice 45 g, Tahina 30 g, Green pepper 3 g, Mashed garlic 3 g, Salt 2.5 g |

| Foul modammas | Dried beans 250 g, Olive oil 35 g, Lemon juice 30 g, Hot green pepper 22 g, Salt 12 g, Cumin 4 g, Garlic 2 g. |

| Sambosik bil sabanikh | Fresh spinach leaves 600 g, Flour 300 g, Olive oil 90 g, Onion 60 g, Lemon juice 30 g, Sugar 15 g, Yeast 10 g, Salt 5 g, Sumac 5 g. |

| Falafel | Dried chickpea 250 g, Onion 105 g, Peeled small beans 100 g, Water 25 g, Green coriander leaves 10 g, Salt 8.5 g, Garlic 7 g, Baking powder 4 g, Sodium bicarbonate 3 g, Black pepper 3 g, Chopped coriander 2.5 g, Cumin 2 g, Hot sauce 2 g. |

| Motabbal bathinjan bil khodaar | Eggplant 388 g, Tomato 150 g, Onion 40 g, Oil 30 g, Lemon juice 20 g, Parsley 15 g, Salt 8 g, Chopped hot green pepper 4 g. |

| Manaqeesh za’ atar | Wheat flour 300 g, Olive oil 105 g, Thyme 45 g, Yeast 15 g, Sugar 15 g, Salt 5 g. |

| Tabbouleh | Parsley 300 g, Tomato 250 g, Lemon juice 150 g, Olive oil 135 g, Onion 100 g, Fine semolina 60 g, Chopped mint 35 g, Salt 18 g. |

| Fatoosh | Tomato 500 g, Cucumber 500 g, Radish 250 g, Lemon juice 120 g, Onion 100 g, Olive oil 75 g, Brown bread 60 g, Parsley 50 g, Fresh mint 25 g, Vinegar 15 g, Sumac 12 g, Garlic 10 g, Salt 4 g. |

| Mosabbaha | Chickpea 80 g, Yoghurt 60 g, Tahina 30 g, Olive oil 15 g, Lemon juice 15 g, Hot pepper 5 g, Garlic 5 g, Salt 2 g. |

| Baqdonsieh | Tahina 120 g, Water 100 g, Parsley 90 g, Lemon juice 50 g, Salt 4 g. |

| Za atar mix | Dried thyme 150 g, Roasted sesame 120 g, Sumac 76 g, Oil 40 g, Salt 11 g. |

References

- Savvaidis, I.N.; Al Katheeri, A.; Lim, S.-H.E.; Lai, K.-S.; Abushelaibi, A. Traditional Foods, Food Safety Practices, and Food Culture in the Middle East; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- A Taste of Tradition: Arabic Sweets in Qatar in Weddings and Celebrations. 2023. Available online: https://chocolaparis.qa/blogs/blog/arabic-sweets-in-qatar (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Global Clinical Practice Recommendations for Managing Type 2 Diabetes. Available online: https://idf.org/media/uploads/2025/04/IDF_Rec_2025.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Al-Thani, M.; Al-Thani, A.A.; Al-Chetachi, W.; Khalifa, S.E.; Vinodson, B.; Al-Malki, B.; Haj Bakri, A.; Akram, H. Situation of Diabetes and Related Factors Among Qatari Adults: Findings From a Community-Based Survey. JMIR Diabetes 2017, 2, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, S.F.; O’Flaherty, M.; Critchley, J.; Abu-Raddad, L.J. Forecasting the burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Qatar to 2050: A novel modeling approach. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 137, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bays, H.E.; Antoun, J.; Censani, M.; Bailony, R.; Alexander, L. Obesity pillars roundtable: Obesity and individuals from the Mediterranean region and Middle East. Obes. Pillars 2022, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, O.; Al Sifri, S.; Hassanein, M.; Al Dawish, M.; Al-Dahash, R.A.; Alawadi, F.; Jarrah, N.; Ballout, H.; Hegazi, R.; Amin, A.; et al. The Transcultural Diabetes Nutrition Algorithm: A Middle Eastern Version. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaradi, M.; Ouagueni, A.; Khatib, R.; Attieh, G.; Bawadi, H.; Shi, Z. Dietary patterns and glycaemic control among Qatari adults with type 2 diabetes. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4506–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaghrbi, R.; Alyamani, R.; Aliwi, L.; Moawad, J.; Hussain, A.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Z. Association between Dietary Pattern, Weight Loss, and Diabetes among Adults with a History of Bariatric Surgery: Results from the Qatar Biobank Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Thani, M.; Al Thani, A.A.; Al-Chetachi, W.; Al Malki, B.; Khalifa, S.A.H.; Bakri, A.H.; Hwalla, N.; Naja, F.; Nasreddine, L. Adherence to the Qatar dietary guidelines: A cross-sectional study of the gaps, determinants and association with cardiometabolic risk among st adults. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Doherty Jensen, K.; Holm, L. Preferences, quantities and concerns: Socio-cultural perspectives on the gendered consumption of foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djuric, Z.; Vanloon, G.; Radakovich, K.; Dilaura, N.M.; Heilbrun, L.K.; Sen, A. Design of a Mediterranean exchange list diet implemented by telephone counseling. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamiya, H.; Utsunomiya, K.; Watada, H.; Kawanami, D.; Sato, J.; Kitada, M.; Koya, D.; Harada, N.; Shide, K.; et al. Medical nutrition therapy and dietary counseling for patients with diabetes-energy, carbohydrates, protein intake and dietary counseling. Diabetol. Int. 2020, 11, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, H.; Waldrop, J.B.; Reynolds, S.S.; Lam, D. Patient-Centered Culturally Tailored Diet for Hospitalized Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutr. Today 2025, 60, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piombo, L.; Nicolella, G.; Barbarossa, G.; Tubili, C.; Pandolfo, M.M.; Castaldo, M.; Costanzo, G.; Mirisola, C.; Cavani, A. Outcomes of Culturally Tailored Dietary Intervention in the North African and Bangladeshi Diabetic Patients in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marri, C.N.A. Tastes of Qatar: The Cuisine of Noof Al-Marri; Qatari-Russian Center for Coorperation Cultural Creative Agency: Doha, Qatar, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bawadi, H.; Akasheh, R.T.; Kerkadi, A.; Haydar, S.; Tayyem, R.; Shi, Z. Validity and Reproducibility of a Food Frequency Questionnaire to Assess Macro and Micro-Nutrient Intake among a Convenience Cohort of Healthy Adult Qataris. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElObeid, T.; Phoboo, S.; Magdad, Z. Proximate and Mineral Composition of Indigenous Qatari Dishes: Comparative Study with Similar Middle Eastern Dishes. J. Food Chem. Nutr. 2015, 3, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Al Nagdy, S.A.; Abd-El Ghani, S.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.O. Chemical assessment of some traditional Qatari dishes. Food Chem. 1994, 49, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O. Food Composition Tables for Kingdom of Bahrain; Arab Center for Nutrition: Manama, Bahrain, 2011; Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/food_composition/documents/pdf/FOODCOMPOSITONTABLESFORBAHRAIN.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Takruri, H.; Al-Ismail, K.; Tayyem, R.; Al-Dabbas, M. Composition of Local Jordanian Food Dishes; Dar Zuhdi for Publishing and Distribution: Amman, Jordan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Eastern Mediterranean Food Information Database (EMFID); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Research, E. ESHA Food Processor Database. Available online: https://www.trustwell.com/products/food-processor-nutrition-analysis-software/ (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Wheeler, M.L.; Franz, M.; Barrier, P.; Holler, H.; Cronmiller, N.; Delahanty, L.M. Macronutrient and energy database for the 1995 Exchange Lists for Meal Planning: A rationale for clinical practice decisions. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996, 96, 1167–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.L.; Daly, A.; Evert, A.; Franz, M.J.; Geil, P.; Holzmeister, L.A.; Kulkarni, K.; Loghmani, E.; Ross, T.A.; Woolf, P. Choose Your Foods: Exchange Lists for Diabetes, Sixth Edition, 2008: Description and Guidelines for Use. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Abbass, M.M.S. Unhealthy Dietary Habits and Obesity: The Major Risk Factors Beyond Non-Communicable Diseases in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 817808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biandolino, F.; Parlapiano, I.; Denti, G.; Di Nardo, V.; Prato, E. Effect of Different Cooking Methods on Lipid Content and Fatty Acid Profiles of Mytilus galloprovincialis. Foods 2021, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawadi, H.A.; Al-Shwaiyat, N.M.; Tayyem, R.F.; Mekary, R.; Tuuri, G. Developing a food exchange list for Middle Eastern appetizers and desserts commonly consumed in Jordan. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 66, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Zoghbi, E.; Rady, A.; Shankiti, I.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Development of a Lebanese food exchange system based on frequently consumed Eastern Mediterranean traditional dishes and Arabic sweets. F1000Research 2021, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Kalsoom, S.; Khan, A.A. Food Exchange List and Dietary Management of Non-Communicable Diseases in Cultural Perspective. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 33, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisaguano-Tonato, A.M.; Herrera-Fontana, M.E.; Vayas-Rodriguez, G. Food exchange list based on macronutrients: Adapted for the Ecuadorian population. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1219947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Shao, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z. Development and validation of a novel food exchange system for Chinese pregnant women. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bawadi, H.A.; Al-Sahawneh, S.A. Developing a meal-planning exchange list for traditional dishes in jordan. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, A.; O’Brien, R.D.H.; Galibois, R.I. Development of a Malian food exchange system based on local foods and dishes for the assessment of nutrient and food intake in type 2 diabetic subjects. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 22, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shovic, A.C. Development of a Samoan nutrition exchange list using culturally accepted foods. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1994, 94, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Lopes, I.; Menal-Puey, S.; Martínez, J.A.; Russolillo, G. Development of a Spanish Food Exchange List: Application of Statistical Criteria to a Rationale Procedure. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, H.Y.; Lee, H.K. Korean Food Exchange System. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 1990, 9, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detopoulou, P.; Aggeli, M.; Andrioti, E.; Detopoulou, M. Macronutrient content and food exchanges for 48 Greek Mediterranean dishes. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orense, C.; Madrid, M.; Santos, N.L.; Lat, H.; Mendoza, D.K. Updating of the Philippine Food Exchange Lists for Meal Planning. Philipp. J. Sci. 2021, 150, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A.; American Diabetes Association; American Dietetic Association. Choose Your Foods: Exchange Lists for Diabetics; American Diabetes Association: Alexandria, VA, USA; American Dietetic Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Lagisetty, P.A.; Priyadarshini, S.; Terrell, S.; Hamati, M.; Landgraf, J.; Chopra, V.; Heisler, M. Culturally Targeted Strategies for Diabetes Prevention in Minority Population. Diabetes Educ. 2017, 43, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeddine, D.I. Lebanon Food System Transformation Pathway. Available online: https://www.unfoodsystemshub.org/docs/unfoodsystemslibraries/national-pathways/lebanon/2024-03-01-national-pathway-lebanon-eng.pdf?sfvrsn=b3a6dad2_3 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

| Food Composition Data Source | No. of Food Items | Selected Food Items | Preparation Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study conducted by El Obeid [18] | 2 | Sweets: Sago (Sagau), Barinoish | Domestically prepared |

| Study conducted by Nagdy et al. [19] | 2 | Sweets: Aigalee, Assedah | Domestically prepared under the supervision of a qualified dietitian. |

| Food composition table of Bahrain [20] | 9 | Sweets: Balleleet, Mahamer, Khabeese, Khanfarooshe, Hesso Elbah, Luqemat, Betheeth Muhalbiya | Domestically prepared |

| Jordanian Food composition table [21] | 21 | Sweets: Konafah na’ema bil jibn, Qatayif bil jibn Maqli, Qatayif bil jooz Maqli, Qatayif bil jibn Mashwi, Qatayif bil jooz Mashwi, Ma’amool ajwa bilsameed, Ma’amool ajwa bil taheen, Mamool bil jooz, Mamool bil fustok Appetizers: Motabbal bathijan bil tahina, Hummus bil tahina, Foul modammas, Sambosik bil sabanikh, Falafel, Motabbal bathinjan bil khodar, Manaqeesh za’ atar, Tabbouleh, Fatoosh, Mosabbaha, Baqdonsieh, Za atar mix | Commercially purchased |

| Dish Group | Major Ingredients | Carbohydrate (g/100 g) | Protein (g/100 g) | Fat (g/100 g) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweets n = 22 | Grain/Flour, Sweetener, Dairy/egg, Fats & oils, Nuts | 0.78 | 0.72 | 0.80 | <0.05 |

| Appetizers n = 12 | Grains/Bread, Legumes/Pulses, Vegetables | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.53 | <0.05 |

| Dish Names | Description | Serving Weight | Serving Size | Carbohydrates (g) | Protein (g) | Fat (g) | Exchange/ Serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balleleet | Sweetened vermicelli flavored with cardamom and saffron | 100 g | 1 small to medium piece | 30.4 | 5.5 | 6 | 1 Starch, 1 Other carbohydrate, 1 Fat |

| Mahamer | Fried Sweet Rice (sucrose & pure corn oil) | 100 g | ½ cup | 49 | 2.9 | 4 | 1.5 Starch, 1.5 Other carbohydrates, 1 Fat |

| Barinoish | Sweet made from rice | 100 g | ½ cup | 36.8 | 2 | 0 | 2 Starch, 0.5 Other Carbohydrates |

| Sago (Sagau) | Sago Pudding | 100 g | ½ cup | 58 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 2 Starch, 2 Other Carbohydrates |

| Khabeese | Flavored Semolina cake with sugar syrup and cardamom | 100 g | 2 small pieces | 58.6 | 3.5 | 6.3 | 2 Starch, 2 Other Carbohydrates, 1 Fat |

| Khanfarooshe | Dessert made from ground rice and egg | 100 g | 2 pieces | 50.1 | 6.2 | 10.1 | 1.5 Starch, 1.5 Other carbohydrates, 1 MFM, 1 Fat |

| Hesso | Egg and watercress sweet | 100 g | ½ cup | 15 | 2.9 | 7.1 | 1 Starch, 1 Fat |

| Elbah | Egg with milk pudding | 100 g | ½ cup | 18 | 4.3 | 3.3 | 1 Other Carbohydrate, 0.5 Low-fat milk |

| Aigalee | Baked Cardamom cake with egg | 100 g | 1 medium slice | 19.1 | 8.4 | 35.8 | 1 starch, 1 vegetable, 1 MFM, 6 fat |

| Asseda (assedah) | Pudding-like dessert with wheat flour | 100 g | ½ cup | 17.1 | 3.1 | 29 | 1 Starch, 5 Fat |

| Luqemat/ Awameh | Sweet dumplings soaked in sugar syrup | 40 g | 2 small pieces | 28.1 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 1 Starch, 1 Other Carbohydrate, 0.5 Fat |

| Muhalbiya | Rice Pudding | 100 g | ½ cup | 17.6 | 3 | 3 | 1 Starch, 0.5 Fat |

| Betheeth | Dates with Flour | 30 g | 1 piece | 21.3 | 0.7 | 2 | 1 Starch, 0.5 Fat |

| Konafah na’ema bil jibn | Layers of pastry and cheese filled with sugar syrup and cheese | 100 g | Medium-sized piece (piece) | 36 | 10.7 | 16.4 | 1 Starch, 1 Other carbohydrate, 1 MFM, 0.5 Whole-fat milk |

| Qatayif bil jibn Maqli | Deep-fried pancake-like dough stuffed with cheese and dipped in sugar syrup | 40 g | 1 piece | 16.6 | 4 | 4 | 1 Starch, 1 Fat |

| Qatayif bil jooz Maqli | Deep-fried pancake-like dough stuffed with walnuts and dipped in sugar syrup | 45 g | 1 piece | 26.5 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 1 Starch, 0.5 Other carbohydrate, 1 Fat |

| Qatayif bil jibn Mashwi | Grilled pancake-like dough stuffed with cheese and dipped in sugar syrup | 50 g | 1 piece | 12.3 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 1 Starch |

| Qatayif bil jooz Mashwi | Grilled pancake-like dough stuffed with walnuts and dipped in sugar syrup | 50 g | 1 piece | 14 | 3.7 | 8 | 1 Starch, 1.5 Fat |

| Ma’amool ajwa bilsameed | semolina cookies stuffed with dates | 30 g | 1 piece | 17.9 | 2.7 | 5.8 | 1 Starch, 1 Fat |

| Ma’amool ajwa bil taheen | Semolina cookies stuffed with dates and sesame paste | 30 g | 1 piece | 18.6 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 1 Starch, 1 Fat |

| Mamool bil jooz | Semolina cookie filled with walnuts | 30 g | 1 piece | 13.3 | 2.5 | 7.3 | 1 Starch, 1 Fat |

| Mamool bil fustok | A cookie filled with pistachio | 35 g | 1 piece | 6 | 2 | 2.6 | 0.5 Starch. 0.5 Fat |

| Dish Names | Description | Serving Weight | Serving Size | Carbohydrates (g) | Protein (g) | Fat (g) | Exchange/ Serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motabbal bathijan bil tahina | Roasted eggplant and sesame blend as a dip | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 6.9 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 1 Vegetable, 2 Fat |

| Hummus bil tahina | Boiled chickpeas and sesame paste blend as a dip | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 14 | 7.5 | 10.6 | 1 Starch, 1 LM, 1.5 Fat |

| Foul modammas | Fava bean dip | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 14.7 | 7.6 | 4.9 | 1 Starch, 1 LM, 1 Fat |

| Sambosik bil sabanikh | Fried spinach-stuffed pastry | 70 g | 1 medium-sized piece | 24.8 | 4 | 8.8 | 1 Starch 1.5 Vegetable, 1.5 Fat |

| Falafel | A paste of broad beans and/or chickpeas that is deep-fried in oil | 100 g | 4 pieces | 27.1 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 1.5 Starch, 1 LM, 2 Fat |

| Motabbal bathinjan bil khodaar | Roasted eggplant and vegetables blend as a dip | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 5.6 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 1 Vegetable, 1 Fat |

| Manaqeesh za’ atar | Bread with dried thyme and sesame pie | 50 g | ½ piece | 23.4 | 5.1 | 12.5 | 1 Starch, 2 Fat |

| Tabbouleh | Salad of parsley, tomatoes, onion, lemon juice, olive oil, and bulghur | 100 g | 3/4 cup | 8.6 | 2.9 | 10.9 | 1 Vegetable. 2 Fat |

| Fatoosh | Vegetable salad with fried bread | 100 g | 1 cup | 7.6 | 2.1 | 5.9 | 1 Vegetable, 1 Fat |

| Mosabbaha | Boiled chickpeas, yogurt, and tahini blend as a dip | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 15.8 | 7.4 | 9.5 | 1 Starch, 1 LM, 1.5 Fat |

| Baqdonsieh | Dip with sesame paste | 100 g | 1/2 cup | 5.5 | 7.6 | 19.6 | 0.5 Vegetable, 1 LM, 3.5 Fats |

| Za atar mix | Arabic spice blend | 20 g | 2 tbsp | 4.5 | 3.7 | 6.5 | 1 Vegetable, 1 Fat |

| Exchange Group | Standard International Value (Approximate) | Mean Calculated Nutrient Profile in GCC List (g/Exchange) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starch (1 Carbohydrate serving) | 15 g Carbohydrate 3 g Pro 0–1 g Fat | 15.3 ± 4.1 g Carbohydrate 3.7 ± 1.4 g Pro 4.1 ± 3.2 g Fat | CHO and protein are consistent. Fat content is higher, reflecting the use of clarified butter (samn) and oils in traditional preparation. |

| Fat (1 Fat serving) | 5 g Fat 0 g Carbohydrate 0 g Protein | 5.1 ± 1.4 g Fat 3.1 ± 1.5 g Carbohydrate 1.2 ± 0.9 g Protein | Fat content is consistent. Small amounts of CHO/Pro are noted, attributed to composite ingredients (e.g., tahini and nuts) in appetizers. |

| Region/Country | Year | No. of Sweet/Appetizer Items | Mean CHO per Serving (g) | Mean Fat per Serving (g) | Key Cultural Feature Addressed | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan | 2009 | 40 (20 appetizers + 20 desserts) | 30–50 | 10–20 | Levantine appetizers & wheat-based desserts | [28] |

| Lebanon | 2021 | 30+ (dishes + Arabic sweets) | 25–40 | 12–25 | Baklava/knāfeh sweets; smaller Levantine portions | [29] |

| Pakistan | 2017 | Limited (milk/grain sweets) | ~45 | <15 | Rice/wheat-based, low-fat confections | [30] |

| China (pregnancy) | 2023 | Included (sweet snacks) | 40–50 | 10–15 | Rice/flour-based; pregnancy-adapted | [32] |

| Ecuador | 2023 | General (sweets/staples incl.) | 35–45 | <10 | Plantain/tuber-based; low-fat staples | [31] |

| Mali (diabetes) | 2009 | Limited (sugar-added foods) | 15–25 | <5 | Local staples; minimal sweets for T2D control | [34] |

| Samoa | 1994 | Culturally accepted (dishes/sweets) | 35–45 | 10–15 | Coconut-rich; high sodium/fat highlights | [35] |

| GCC/ Qatar | 2025 | 34 | 45–60 | 15–35 | Syrup/ghee-fried sweets dominant; legume/veg appetizers | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdul Majeed, S.; Tayyem, R. Development of a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Sweets and Appetizers in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Insights from Qatar. Nutrients 2026, 18, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010117

Abdul Majeed S, Tayyem R. Development of a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Sweets and Appetizers in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Insights from Qatar. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdul Majeed, Safa, and Reema Tayyem. 2026. "Development of a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Sweets and Appetizers in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Insights from Qatar" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010117

APA StyleAbdul Majeed, S., & Tayyem, R. (2026). Development of a Meal-Planning Exchange List for Traditional Sweets and Appetizers in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Insights from Qatar. Nutrients, 18(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010117