Aloysia citrodora Polyphenolic Extract: From Anti-Glycative Activity to In Vitro Bioaccessibility and In Silico Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Evaluation of Fructosamine Formation

2.4. Evaluation of MGO and GO Trapped by the RP-UHPLC-DAD Method

2.5. Evaluation of Vesperlysine-like and Argpyrimidine-like AGE Formation

2.6. Analysis of the Metabolic Profile by RP-HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn Method

2.7. In Vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion

2.8. Evaluation of Extract Bioaccessibility

2.9. Molecular Modeling Studies

3. Results and Discussions

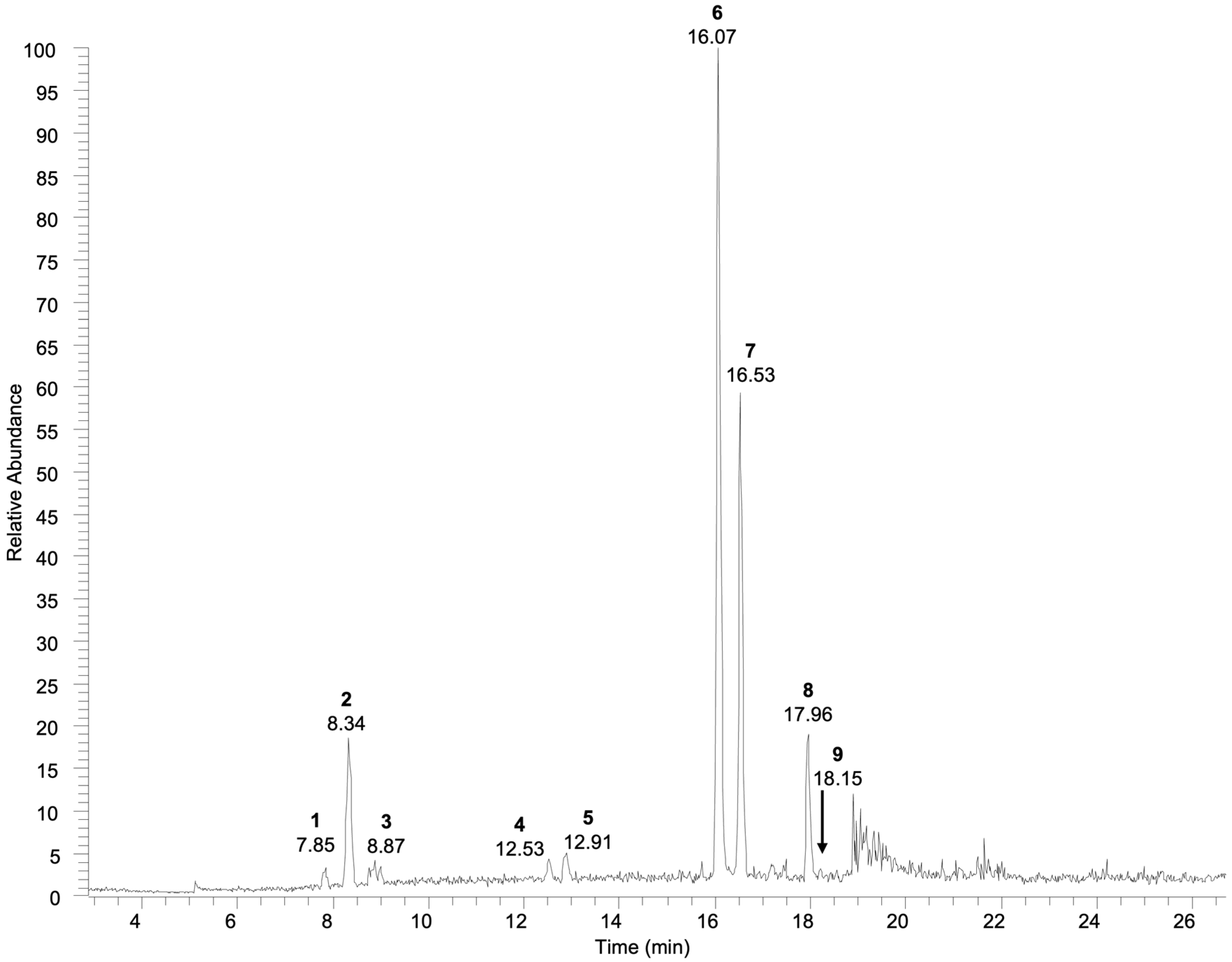

3.1. Chacterization of the Metabolic Profile of A. citrodora Leaf Extract by RP-HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn and Method Validation

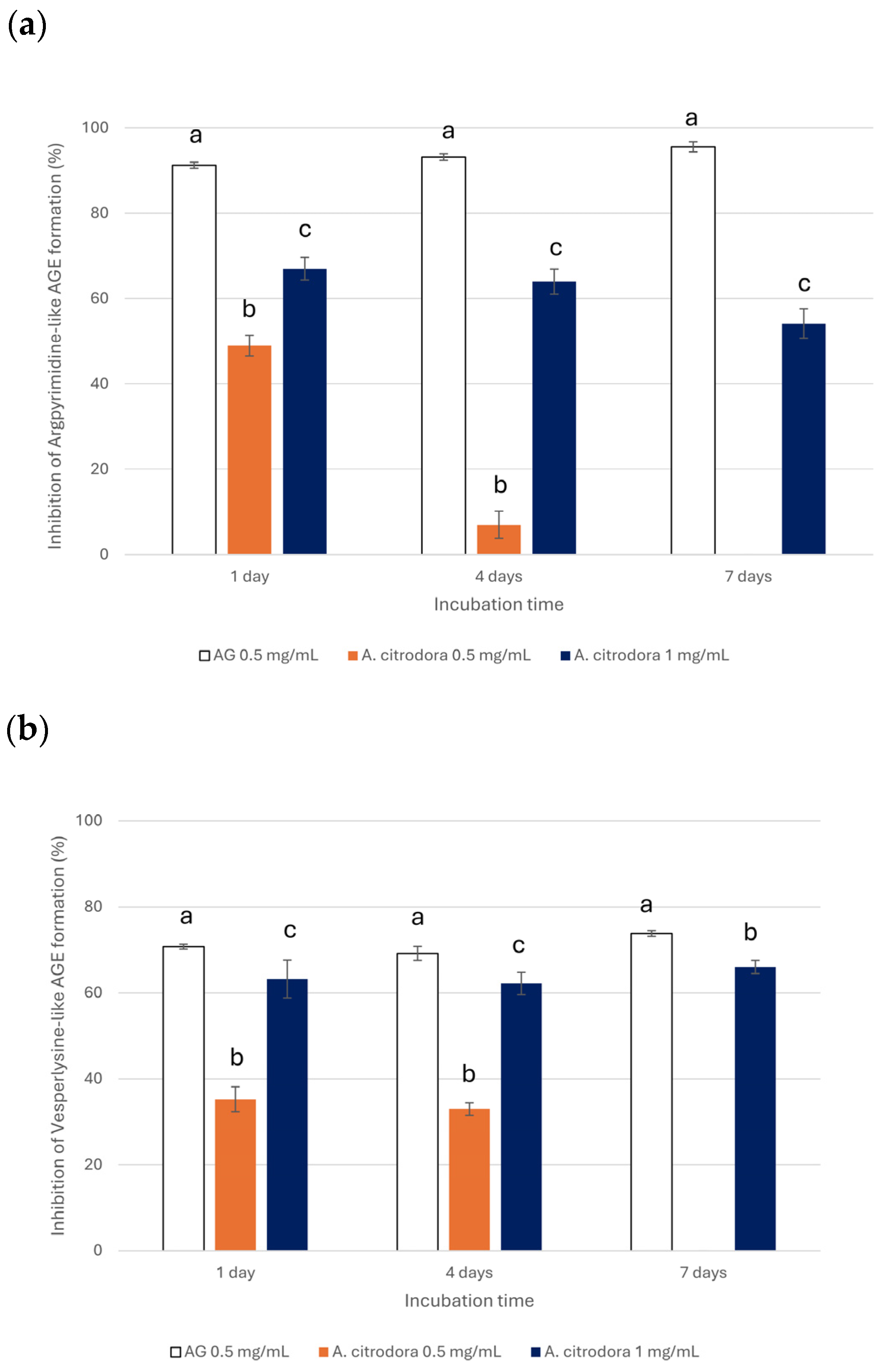

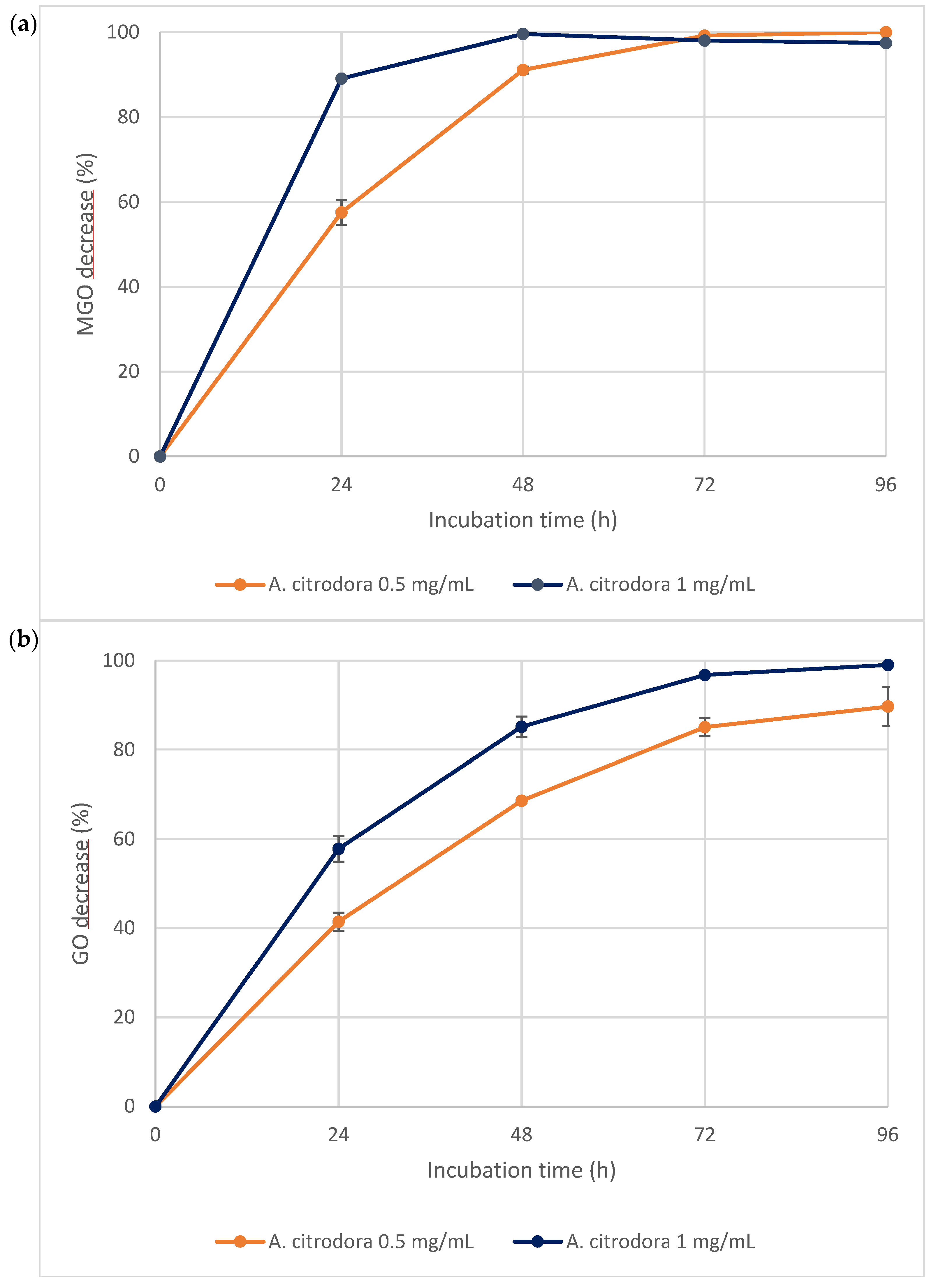

3.2. Evaluation of Inhibitory Effects of A. citrodora Extract on the Glycation Reaction

3.3. Investigation into the Effect of In Vitro Static Digestion on A. citrodora Extract

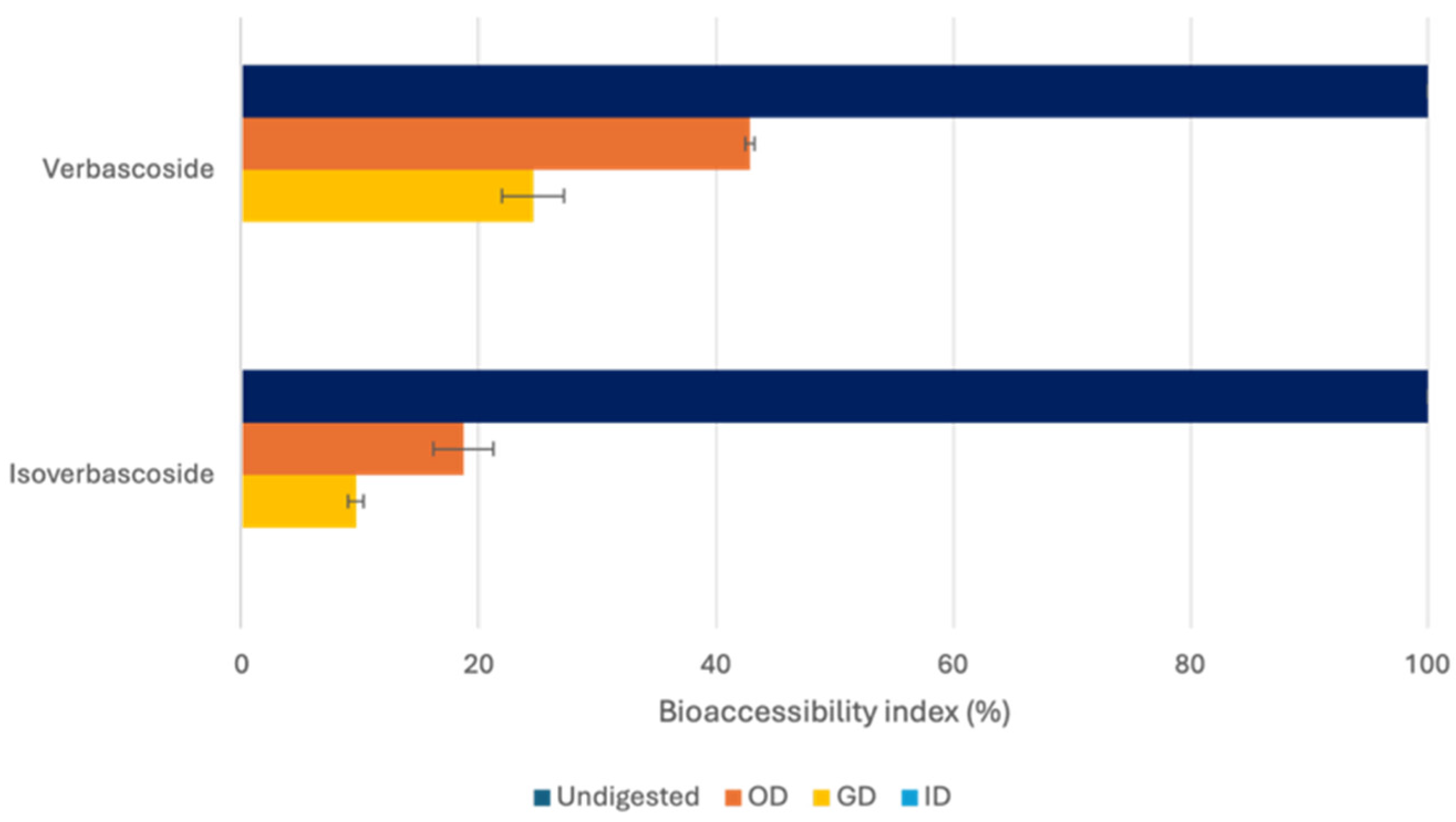

3.3.1. Evaluation of the A. citrodora Extract Bioaccessibility

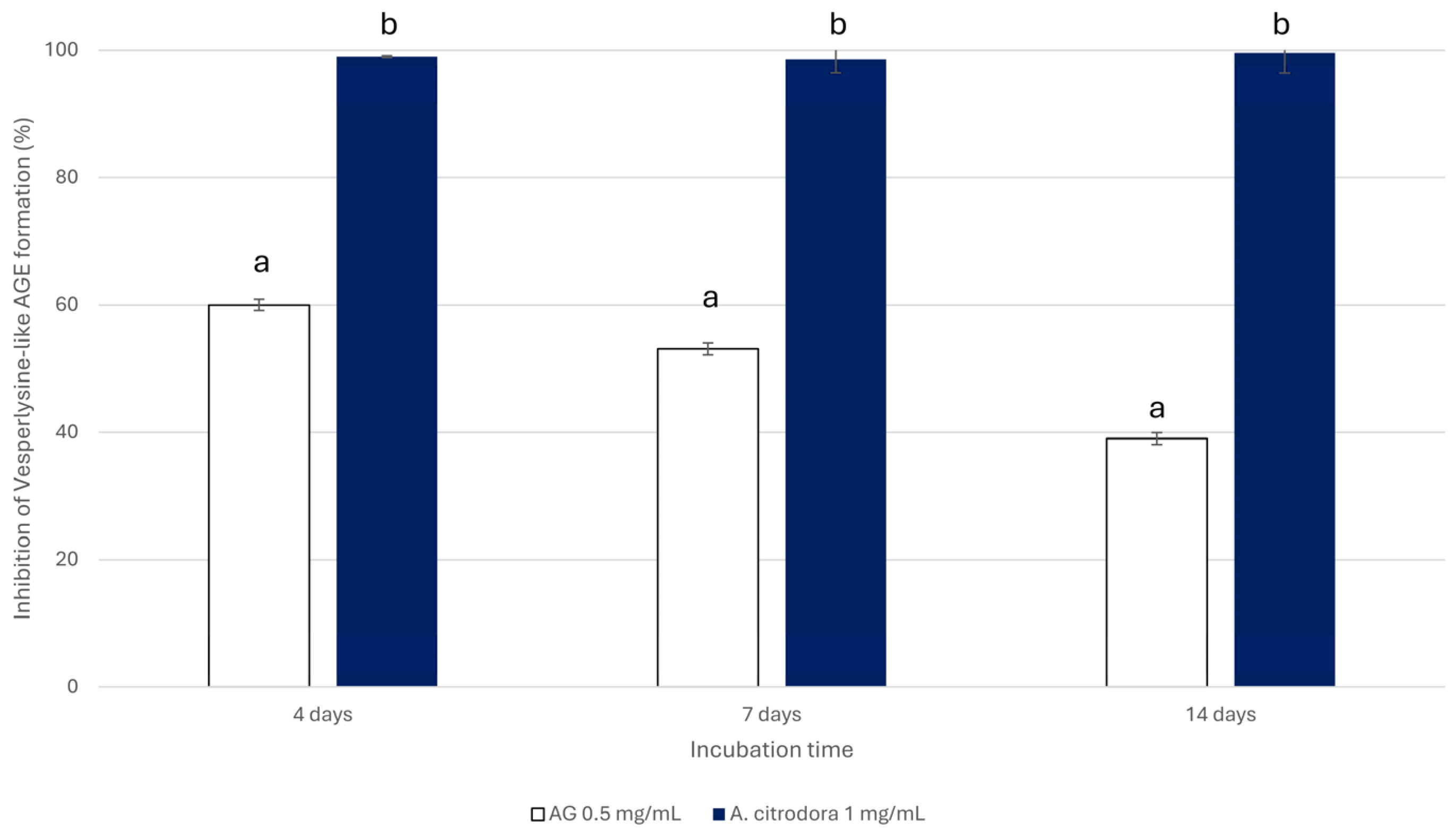

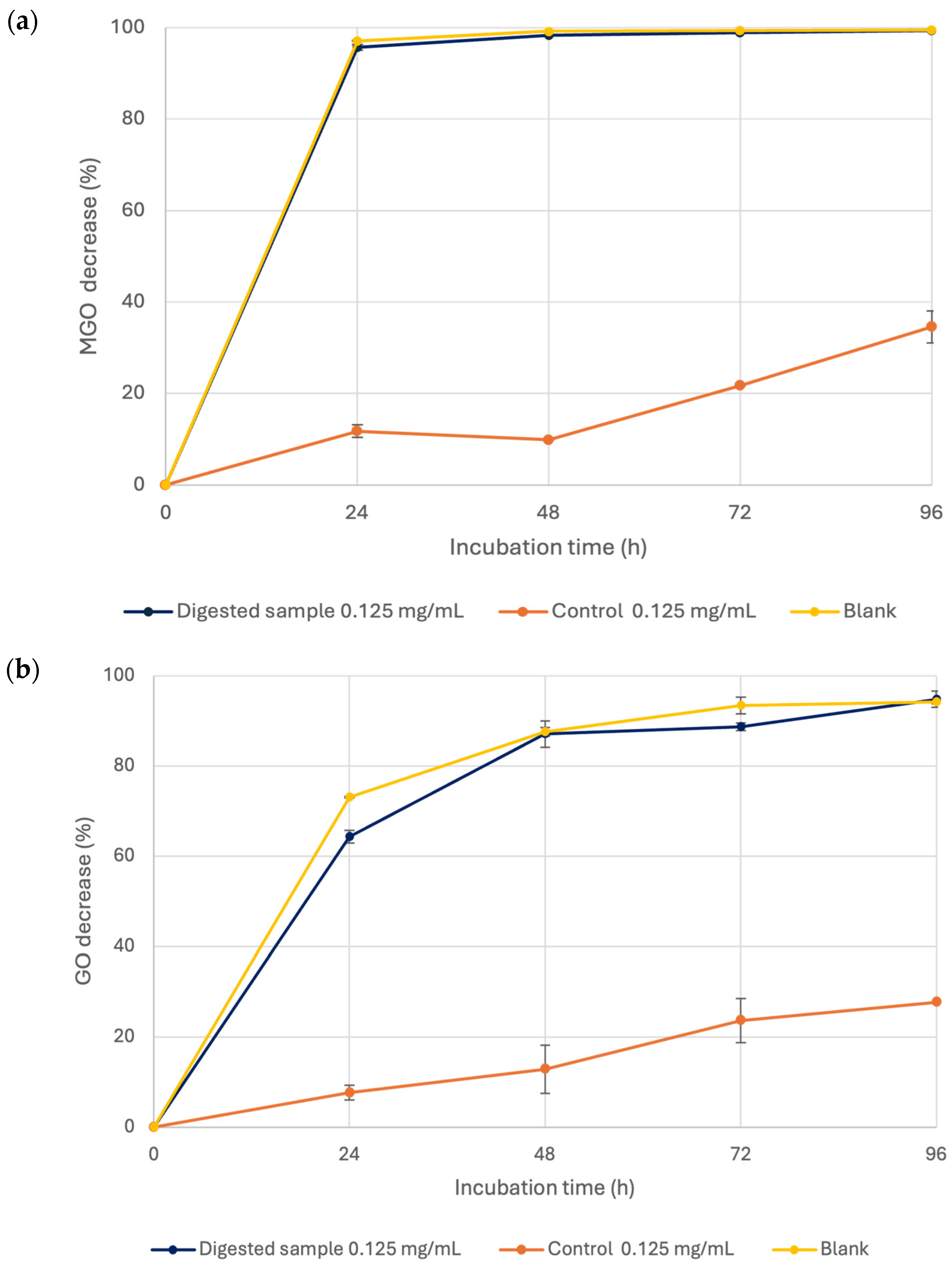

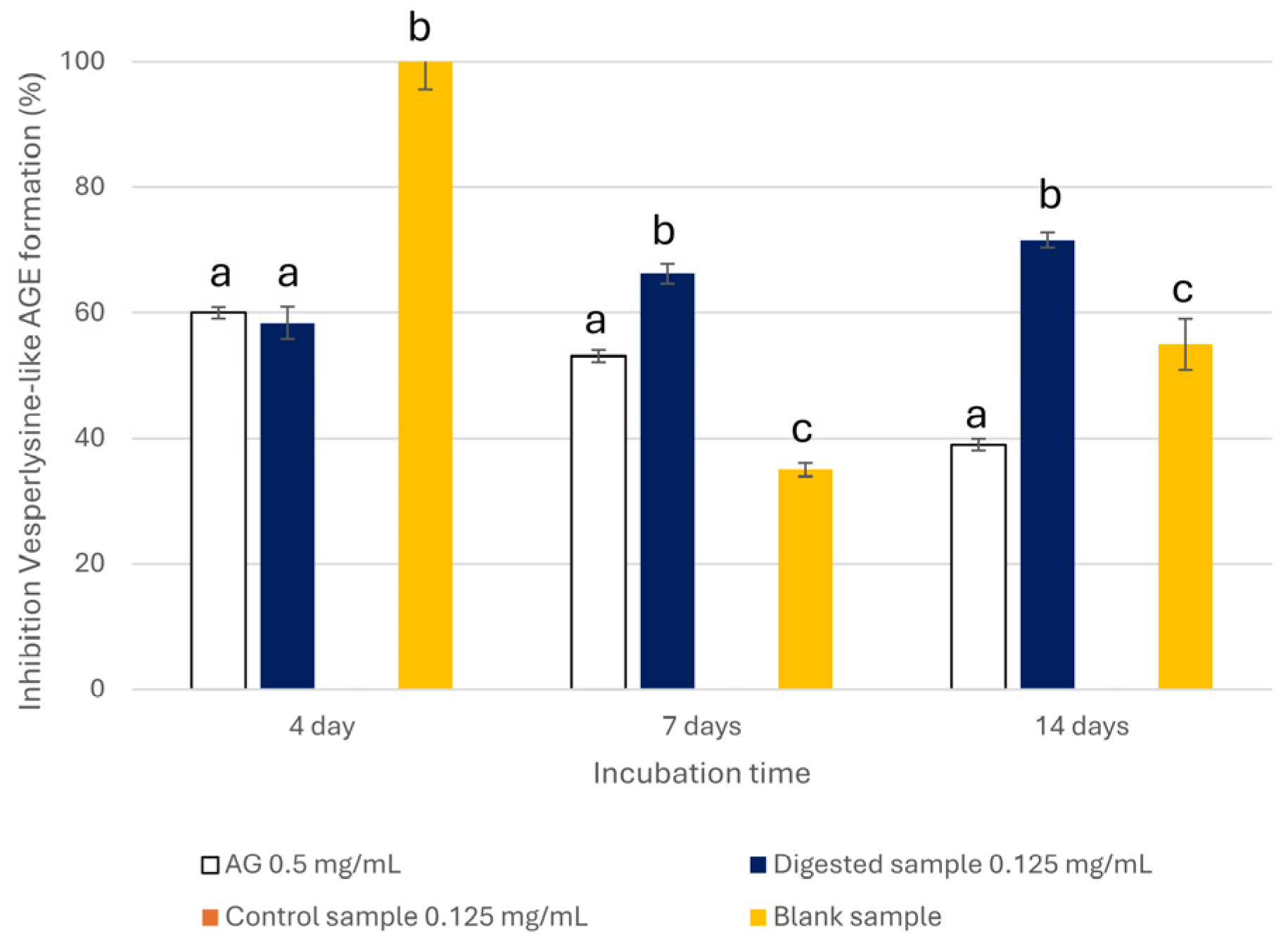

3.3.2. Anti-Glycative Properties of the A. citrodora Extract Bioaccessible Fraction

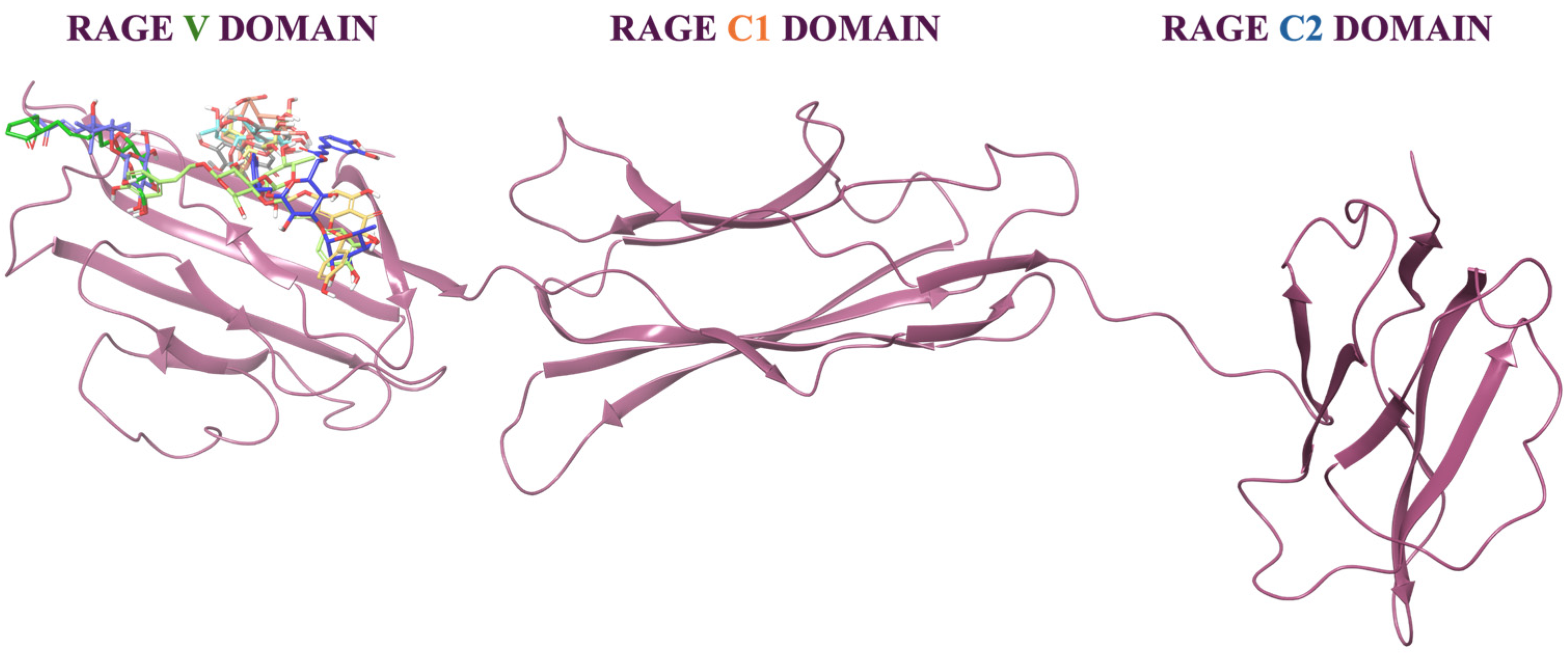

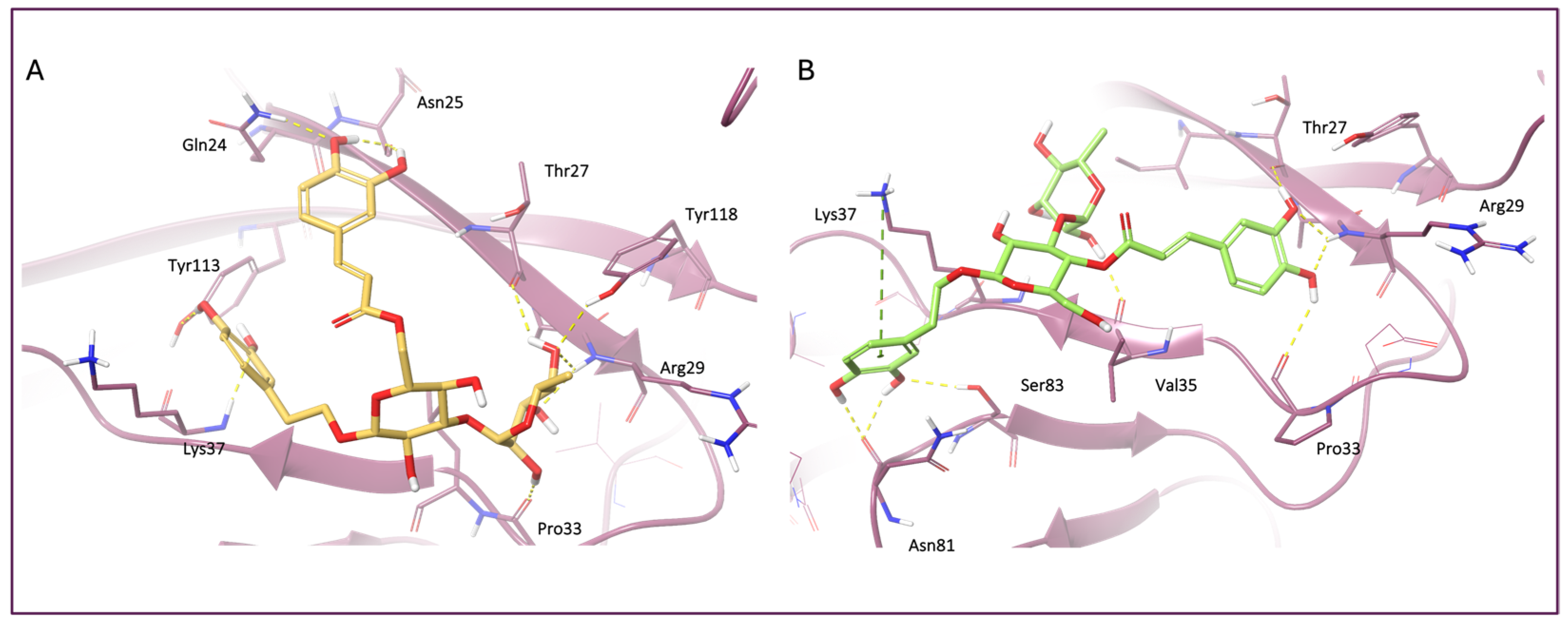

3.4. Molecular Docking and MM-GBSA Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Maharik, N.; Salama, Y.; Al-Hajj, N.; Jaradat, N.; Jobran, N.T.; Warad, I.; Hidmi, A. Chemical composition, anticancer, antimicrobial activity of Aloysia citriodora Palau essential oils from four different locations in Palestine. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahramsoltani, R.; Rostamiasrabadi, P.; Shahpiri, Z.; Marques, A.M.; Rahimi, R.; Farzaei, M.H. Aloysia citrodora Paláu (Lemon verbena): A review of phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 222, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, J.A.B.; Álvarez-Rivera, G.; Costa, A.S.; Machado, S.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E.; Alves, R.C. Contribution of phenolics and free amino acids on the antioxidant profile of commercial lemon verbena infusions. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, S.; Khan, S.; Almatroudi, A.; Khan, A.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Almatroodi, S.A.; Rahmani, A.H. A review on mechanism of inhibition of advanced glycation end products formation by plant derived polyphenolic compounds. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistoli, G.A.; De Maddis, D.; Cipak, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Advanced glycoxidation and lipoxidation end products (AGEs and ALEs): An overview of their mechanisms of formation. Free Rad. Res. 2013, 47, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twarda-Clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs): Formation, chemistry, classification, receptors, and diseases related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Inhibitory effect of phenolic compounds and plant extracts on the formation of advanced glycation end products: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Far, A.H.; Sroga, G.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Mousa, S.A. Role and mechanisms of RAGE–ligand complexes and RAGE-inhibitors in cancer progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. Novel advances in inhibiting advanced glycation end product formation using natural compounds. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velichkova, K.; Foubert, K.; Pieters, L. Natural products as a source of inspiration for novel inhibitors of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) formation. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 780–801. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F.; Peng, H. Bioaccessibility and bioavailability of phenolic compounds. J. Food Bioact. 2018, 4, 11–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasera, G.B.; de Camargo, A.C.; de Castro, R.J.S. Bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds using the standardized INFOGEST protocol: A narrative review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 260–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maietta, M.; Colombo, R.; Lavecchia, R.; Sorrenti, M.; Zuorro, A.; Papetti, A. Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus) waste as a natural source of carbonyl trapping and antiglycative agents. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesías, M.; Navarro, M.; Gökmen, V.; Morales, F.J. Antiglycative effect of fruit and vegetable seed extracts: Inhibition of AGE formation and carbonyl-trapping abilities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferron, L.; Colombo, R.; Mannucci, B.; Papetti, A. A new Italian purple corn variety (Moradyn) byproduct extract: Antiglycative and hypoglycemic in vitro activities and preliminary bioaccessibility studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carriere, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—An international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodkorb, A.; Egger, L.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Assunção, R.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Boutrou, R.; Carrière, F.; et al. INFOGEST static in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal food digestion. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 991–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maietta, M.; Colombo, R.; Corana, F.; Papetti, A. Cretan tea (Origanum dictamnus L.) as a functional beverage: An investigation on antiglycative and carbonyl trapping activities. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretto, G.; Colombo, R.; Negri, S.; Cena, H.; Vailati, L.; Papetti, A. Italian biodiversity: A source of edible plant extracts with protective effects against advanced glycation end product-related diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICH Guideline. Validation of Analytical Procedures Q2 (R2); ICH: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Colasanto, A.; Disca, V.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Coisson, J.D.; Arlorio, M.; Locatelli, M. Bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds during simulated gastrointestinal digestion of black rice (Oryza sativa L., cv. Artemide). Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatime, L.; Betzer, C.; Jensen, R.K.; Mortensen, S.; Jensen, P.H.; Andersen, G.R. The structure of the RAGE: S100A6 complex reveals a unique mode of homodimerization for S100 proteins. Structure 2016, 24, 2043–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: Protein Preparation Wizard; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: Prime; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: Desmond Molecular Dynamics System; D.E. Shaw Research: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: LigPrep; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: Epik; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: Glide; Schrödinger LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Greenidge, P.A.; Kramer, C.; Mozziconacci, J.C.; Wolf, R.M. MM/GBSA binding energy prediction on the PDBbind data set: Successes, failures, and directions for further improvement. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2013, 53, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release, 2020-4: MacroModel; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2020.

- Jorgensen, W.; Maxwell, D.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom froce field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Xue, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, X. Studies of iridoid glycosides using liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 21, 3039–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Song, S. Screening and identification of multi-components in Re Du Ning injections using LC/TOF-MS coupled with UV-irradiation. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Xing, J.; Liu, Z.; Song, F. A strategy for identification and structural characterization of compounds from Gardenia jasminoides by integrating macroporous resin column chromatography and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry combined with ion-mobility spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1452, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, H.; Wen, J.; Fan, G.; Chai, Y.; Wu, Y. Fragmentation study of iridoid glycosides including epimers by liquid chromatography–diode array detection/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and its application in metabolic fingerprint analysis of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 24, 2520–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Sun, J.-Z.; Xu, S.-Z.; Cai, Q.; Liu, Y.-Q. Rapid characterization and identification of chemical constituents in Gentiana radix before and after wine-processing by UHPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap MSn. Molecules 2018, 23, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Weston, P.A.; Gu, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Z. Identification of phytotoxic metabolites released from Rehmannia glutinosa suggest their importance in the formation of its replant problem. Plant Soil 2019, 441, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Weston, L.A.; Li, M.; Zhu, X.; Weston, P.A.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Z. Rehmannia glutinosa replant issues: Root exudate–rhizobiome interactions clearly influence replant success. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirantes-Piné, R.; Funes, L.; Micol, V.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. High-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection coupled to electrospray time-of-flight and ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry to identify phenolic compounds from a lemon verbena extract. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 5391–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; Cerretani, L.; García-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of Solanum tuberosum L. (potato) leaves by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirantes-Piné, R.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Characterization of phenolic and other polar compounds in a lemon verbena extract by capillary electrophoresis–electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2010, 33, 2818–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Pellati, F.; Graziosi, R.; Brighenti, V.; Pinetti, D.; Bertelli, D. Identification and determination of bioactive phenylpropanoid glycosides of Aloysia polystachya (Griseb. et Moldenke) by HPLC-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 166, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, X.; Saleri, F.; Guo, M. Analysis of flavonoids in Rhamnus davurica and its antiproliferative activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojilov, D.; Manolov, S.; Nacheva, A.; Dagnon, S.; Ivanov, I. Characterization of polyphenols from Chenopodium botrys after fractionation with different solvents and study of their in vitro biological activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Avula, B.; Lee, J.; Upton, R.; Khan, I.A. Chemical characterization and quantitative determination of flavonoids and phenolic acids in yerba santa (Eriodictyon spp.) using UHPLC/DAD/Q-ToF. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023, 234, 115570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Marzo, N.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Cádiz-Gurrea, M.D.L.L.; Herranz-López, M.; Micol, V.; Segura-Carretero, A. Relationships between chemical structure and antioxidant activity of isolated phytocompounds from lemon verbena. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V.P.; Aryal, P.; Darkwah, E.K. Advanced glycation end products in health and disease. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.D.; Pandey, B.N.; Mishra, K.P.; Sivakami, S. Amadori product and AGE formation during nonenzymatic glycosylation of bovine serum albumin in vitro. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Biophys. 2002, 6, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, T.; Sang, S.; Lv, L. Quercetin inhibits advanced glycation end product formation by trapping methylglyoxal and glyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12152–12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadowska-Bartosz, I.; Galiniak, S.; Bartosz, G. Kinetics of glycoxidation of bovine serum albumin by glucose, fructose and ribose and its prevention by food components. Molecules 2014, 19, 18828–18849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Lu, Y.L.; Han, C.H.; Hou, W.C. Inhibitory activities of acteoside, isoacteoside, and its structural constituents against protein glycation in vitro. Bot. Stud. 2013, 54, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I.; Gołąb, K.; Gburek, J.; Wysokińska, H.; Matkowski, A. Inhibition of advanced glycation end-product formation and antioxidant activity by extracts and polyphenols from Scutellaria alpina L. and S. altissima L. Molecules 2016, 21, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasarri, M.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Ivanova Stojcheva, E.; Bilia, A.R.; Degl’Innocenti, D. Olea europaea L. leaves as a source of anti-glycation compounds. Molecules 2024, 29, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsisvalle, S.; Panarello, F.; Longhitano, G.; Siciliano, E.A.; Montenegro, L.; Panico, A. Natural flavones and flavonols: Relationships among antioxidant activity, glycation, and metalloproteinase inhibition. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Miroliaei, M. Role of structural peculiarities of flavonoids in suppressing AGEs generated from HSA/Glucose system. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 6296–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, B.J.; Deng, S.; Uwaya, A.; Isami, F.; Abe, Y.; Yamagishi, S.I.; Jensen, C.J. Iridoids are natural glycation inhibitors. Glycoconj. J. 2016, 33, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, M.; Morales, F.J. Mechanism of reactive carbonyl species trapping by hydroxytyrosol under simulated physiological conditions. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alminger, M.; Aura, A.M.; Bohn, T.; Dufour, C.; El, S.N.; Gomes, A.; Karakaya, S.; Martínez-Cuesta, M.C.; McDougall, G.J.; Requena, T.; et al. In vitro models for studying secondary plant metabolite digestion and bioaccessibility. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Kumar, V.; Nayak, S.K.; Wadhwa, P.; Kaur, P.; Sahu, S.K. Alpha-amylase as molecular target for treatment of diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021, 98, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, A.; Linsalata, V.; Lattanzio, V.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Verbascosides from olive mill waste water: Assessment of their bioaccessibility and intestinal uptake using an in vitro digestion/Caco-2 model system. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, H48–H54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, V.; Kreft, S.; Benković, E.T.; Ivanović, N.; Stanković, M.S. Chemical profile, antioxidant activity and stability in stimulated gastrointestinal tract model system of three Verbascum species. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 89, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Huang, W.; Li, M.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, M.; Lu, B. Bioaccessibility and absorption mechanism of phenylethanoid glycosides using simulated digestion/Caco-2 intestinal cell models. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4630–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque-Soto, C.; Quirantes-Piné, R.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Characterization and influence of static in vitro digestion on bioaccessibility of bioactive polyphenols from an olive leaf extract. Foods 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Imperio, M.; Cardinali, A.; D’Antuono, I.; Linsalata, V.; Minervini, F.; Redan, B.W.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Stability–activity of verbascoside, a known antioxidant compound, at different pH conditions. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound n.# | Rt (Min) | UV-Vis λmax | [M-H]− (m/z) | Fragmentation MSn (% Base Peak) | Identification | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.85 | 238 | 437 1 | MS2[436]: 391 (100) MS3[391]: 391 (46), 229 (24), 211 (8), 185 (30), 167 (100), 149 (45) | Shanzhiside | [32,33] |

| 2 | 8.34 | 238 | 419 1 | MS2[418]: 373(100) MS3[373]: 211 (21), 167 (18), 149 (68), 123 (100) | Geniposidic acid | [34,35] |

| 3 | 8.87 | 238 | 421 1 | MS2[420]: 375 (100) MS3[375]: 213 (54), 169 (67), 151 (100), 125 (57) | Loganic acid | [36] |

| 4 | 12.53 | 240 | 433 1 | MS2[433]: 387 (100), 225 (13) | Rehmaionoside C | [37,38,39] |

| 5 | 12.91 | 240 | 387 | MS2[387]: 207 (50), 163 (100) | Tuberonic acid glucoside | [40,41] |

| 6 | 16.07 | 220, 250, 295, 330 | 623 | MS2[623]: 461 (100) | Verbascoside 2 | [42] |

| 7 | 16.53 | 220, 250, 295, 330 | 623 | MS2[623]: 461 (100) | Isoverbascoside | [42] |

| 8 | 17.96 | 215, 275, 335 | 299 | MS2[299]: 284 (100) | Rhamnocitrin | [43] |

| 9 | 18.15 | 227, 335 | 329 | MS2[329]: 314 (100), 299 (2) | Jaceosidin | [44,45] |

| Compound | Undigested Sample (µg/mL) | OC (µg/mL) | OD (µg/mL) | GC (µg/mL) | GD (µg/mL) | IC (µg/mL) | ID (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbascoside | 7.40 ± 0.84 a | 3.57 ± 0.08 b | 3.16 ± 0.03 c | 1.81 ± 0.15 d | 1.38 ± 0.19 d | nd | nd |

| Isoverbascoside | 4.72 ± 0.29 a | 1.20 ± 0.04 b | 1.16 ± 0.12 b | 0.55 ± 0.036 c | 0.45 ± 0.03 c | nd | nd |

| Compounds | Docking Score | MM-GBSA ΔG Bind |

|---|---|---|

| Isoverbascoside | −5.98 | −85.38 |

| Verbascoside | −5.37 | −67.68 |

| Loganic acid | −5.14 | −63.68 |

| Tuberonic acid glucoside | −6.09 | −63.51 |

| Rehmaionoside C | −4.28 | −45.93 |

| Geniposidic acid | −5.47 | −45.06 |

| Shanzhiside | −5.71 | −44.82 |

| Rhamnocitrin | −4.57 | −44.12 |

| Jaceosidin | −4.75 | −34.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Moretto, G.; Colombo, R.; Negri, S.; Alcaro, S.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Costa, G.; Papetti, A. Aloysia citrodora Polyphenolic Extract: From Anti-Glycative Activity to In Vitro Bioaccessibility and In Silico Studies. Nutrients 2026, 18, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010115

Moretto G, Colombo R, Negri S, Alcaro S, Ambrosio FA, Costa G, Papetti A. Aloysia citrodora Polyphenolic Extract: From Anti-Glycative Activity to In Vitro Bioaccessibility and In Silico Studies. Nutrients. 2026; 18(1):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010115

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoretto, Giulia, Raffaella Colombo, Stefano Negri, Stefano Alcaro, Francesca Alessandra Ambrosio, Giosuè Costa, and Adele Papetti. 2026. "Aloysia citrodora Polyphenolic Extract: From Anti-Glycative Activity to In Vitro Bioaccessibility and In Silico Studies" Nutrients 18, no. 1: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010115

APA StyleMoretto, G., Colombo, R., Negri, S., Alcaro, S., Ambrosio, F. A., Costa, G., & Papetti, A. (2026). Aloysia citrodora Polyphenolic Extract: From Anti-Glycative Activity to In Vitro Bioaccessibility and In Silico Studies. Nutrients, 18(1), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18010115