Carbohydrate Reduction and a Holistic Model of Care in Diabetes Management: Insights from a Retrospective Multi-Year Audit in New Zealand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Health Care Centres

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Clinical Audit

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

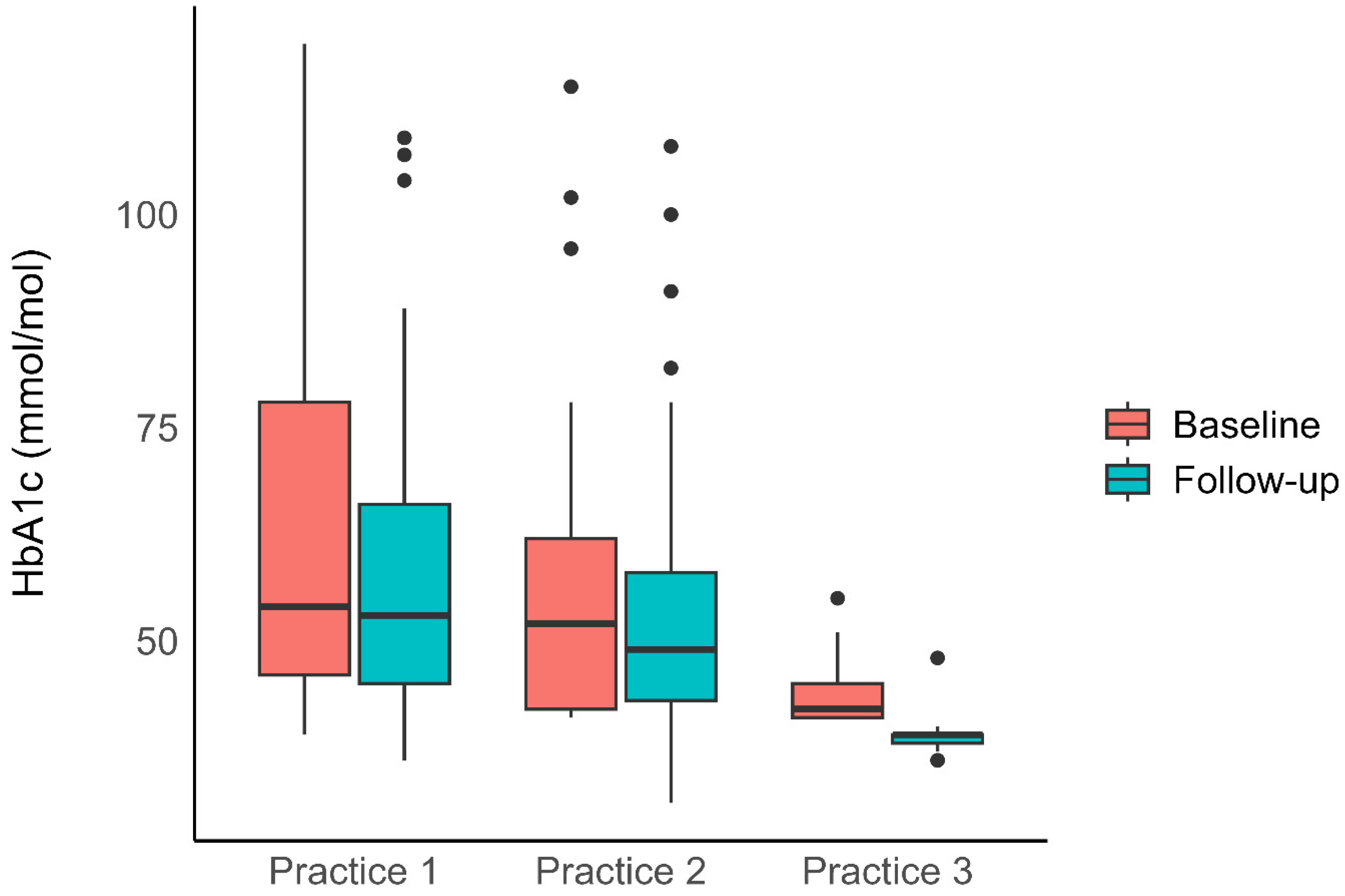

3.1. Blood Sugar Control

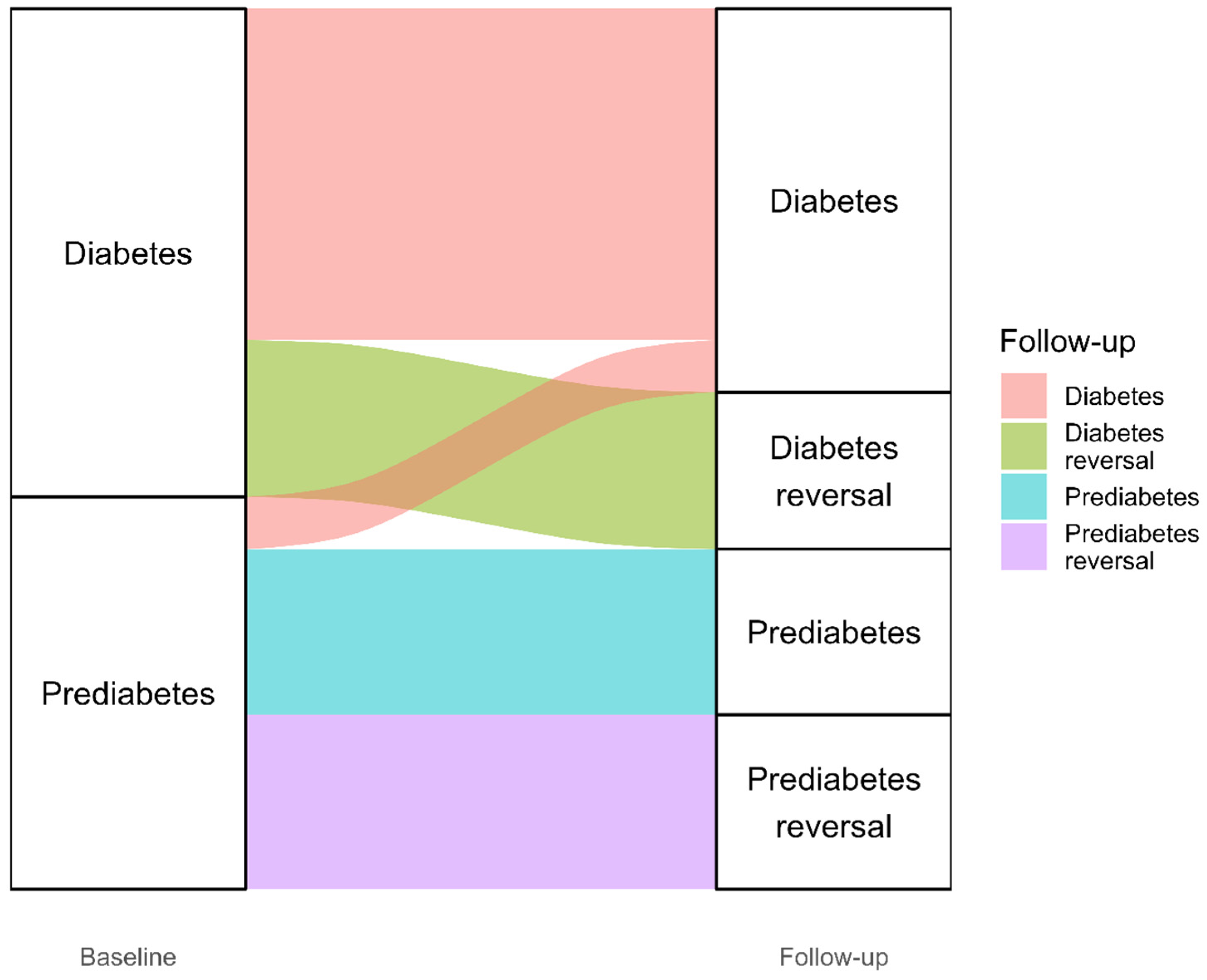

3.2. Diabetes Reversal

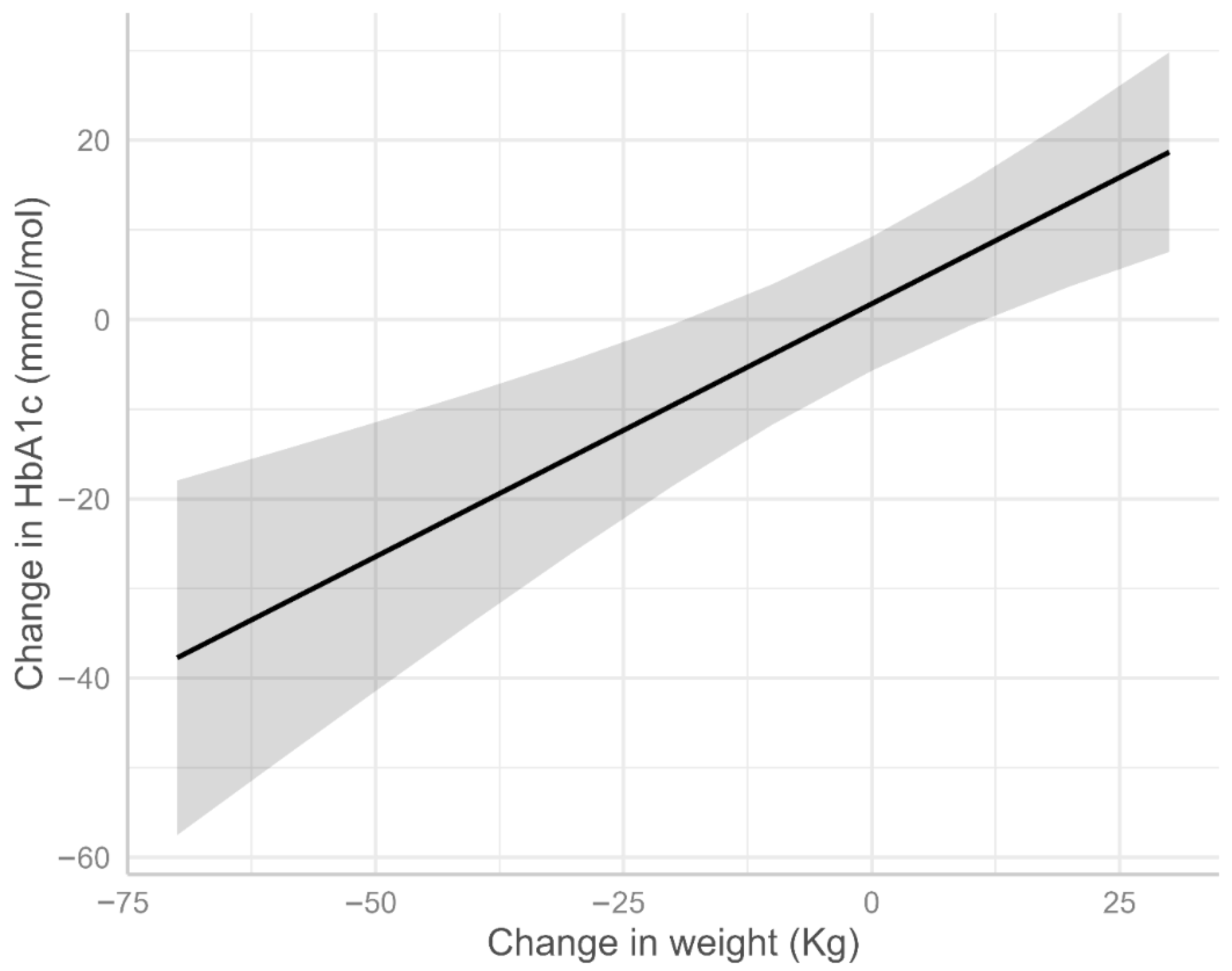

3.3. Factors Associated with HbA1c Change

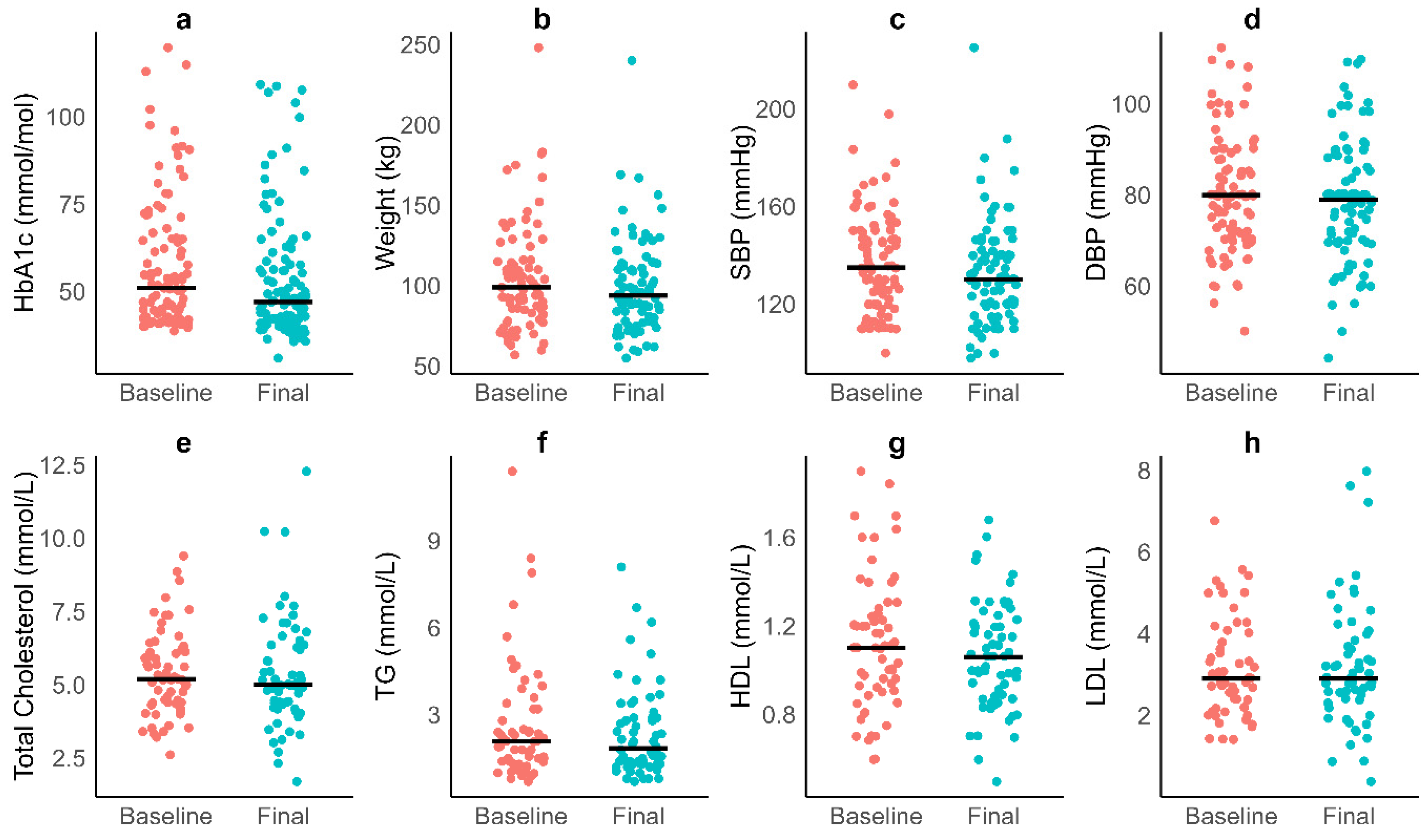

3.4. Cardiometabolic Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmet, P.Z. Diabetes and its drivers: The largest epidemic in human history? Clin. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, S15–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, T.M.; Jakupović, H.; Carrasquilla, G.D.; Ängquist, L.; Grarup, N.; Sørensen, T.I.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T. Obesity, unfavourable lifestyle and genetic risk of type 2 diabetes: A case-cohort study. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A. Hyperinsulinemia and its pivotal role in aging, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanik, M.H.; Xu, Y.; Skrha, J.; Dankner, R.; Zick, Y.; Roth, J. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: Is hyperinsulinemia the cart or the horse? Diabetes Care 2008, 31, S262–S268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Understanding the cause of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaag, A.; Lund, S.S. Non-obese patients with type 2 diabetes and prediabetic subjects: Distinct phenotypes requiring special diabetes treatment and (or) prevention? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2007, 32, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Prediabetes: Ministry of Health. Available online: https://t2dm.nzssd.org.nz/Section-98-Prediabetes (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Ministry of Health. Annual Data Explorer 2023/24: New Zealand Health Survey; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2024.

- Ministry of Health. Living Well with Diabetes: A Plan for People at High Risk of or Living with Diabetes 2015–2020; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKerchar, C.; Barthow, C.; Huria, T.; Jones, B.; Coppell, K.; Hall, R.; Amataiti, T.; Parry-Strong, A.; Muimuiheata, S.; Wright-McNaughton, M. Enablers and barriers to dietary change for Māori with nutrition-related conditions in Aotearoa, New Zealand: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Monte, S.M.; Wands, J.R. Alzheimer’s disease is type 3 diabetes—Evidence reviewed. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2008, 2, 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannucci, E.; Harlan, D.M.; Archer, M.C.; Bergenstal, R.M.; Gapstur, S.M.; Habel, L.A.; Pollak, M.; Regensteiner, J.G.; Yee, D. Diabetes and cancer: A consensus report. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, R.; Barzi, F.; Woodward, M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: Meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. Bmj 2006, 332, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruyt, N.D.; Biessels, G.J.; DeVries, J.H.; Roos, Y.B. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: Pathophysiology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2010, 6, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.L.; Hollingsworth, K.; Aribisala, B.S.; Chen, M.; Mathers, J.; Taylor, R. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: Normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2506–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.; Ramachandran, A.; Yancy, W.S.; Forouhi, N.G. Nutritional basis of type 2 diabetes remission. BMJ 2021, 374, n1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, M.E.; Leslie, W.S.; Barnes, A.C.; Brosnahan, N.; Thom, G.; McCombie, L.; Peters, C.; Zhyzhneuskaya, S.; Al-Mrabeh, A.; Hollingsworth, K.G. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): An open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.A.; Zinn, C.; Delon, C. The application of carbohydrate-reduction in general practice: A medical audit. J. Metab. Health 2023, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glandt, M.; Ailon, N.Y.; Berger, S.; Unwin, D. Use of a very low carbohydrate diet for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: An audit. J. Metab. Health 2024, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, D.; Delon, C.; Unwin, J.; Tobin, S.; Taylor, R. What predicts drug-free type 2 diabetes remission? Insights from an 8-year general practice service evaluation of a lower carbohydrate diet with weight loss. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2023, 6, e000544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie, A.L.; Athinarayanan, S.J.; Van Tieghem, M.R.; Volk, B.M.; Roberts, C.G.; Adams, R.N.; Volek, J.S.; Phinney, S.D.; Hallberg, S.J. 5-Year effects of a novel continuous remote care model with carbohydrate-restricted nutrition therapy including nutritional ketosis in type 2 diabetes: An extension study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 217, 111898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.L.; Flatt, S.W.; Pakiz, B.; Taylor, K.S.; Leone, A.F.; Brelje, K.; Heath, D.D.; Quintana, E.L.; Sherwood, N.E. Weight loss, glycemic control, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in response to differential diet composition in a weight loss program in type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, L.; Landry, M.J.; Rigdon, J.; Gardner, C. Weight, Insulin Resistance, Blood Lipids, and Diet Quality Changes Associated with Ketogenic and Ultra Low-Fat Dietary Patterns: A Secondary Analysis of the DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1220020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, C.D.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Del Gobbo, L.C.; Hauser, M.E.; Rigdon, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Desai, M.; King, A.C. Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: The DIETFITS randomized clinical trial. Jama 2018, 319, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Thompson, C.H.; Noakes, M.; Buckley, J.D.; Wittert, G.A.; Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Brinkworth, G.D. Comparison of low-and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: A randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, C.; Barnard, N.; Katcher, H. A plant-based diet for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMacken, M.; Shah, S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. JGC 2017, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shai, I.; Schwarzfuchs, D.; Henkin, Y.; Shahar, D.R.; Witkow, S.; Greenberg, I.; Golan, R.; Fraser, D.; Bolotin, A.; Vardi, H. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheatley, S.D.; Deakin, T.A.; Arjomandkhah, N.C.; Hollinrake, P.B.; Reeves, T.E. Low carbohydrate dietary approaches for people with type 2 diabetes—A narrative review. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, R.M.; Blanche, P.J.; Rawlings, R.S.; Fernstrom, H.S.; Williams, P.T. Separate effects of reduced carbohydrate intake and weight loss on atherogenic dyslipidemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, S.J.; Gershuni, V.M.; Hazbun, T.L.; Athinarayanan, S.J. Reversing type 2 diabetes: A narrative review of the evidence. Nutrients 2019, 11, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Thompson, C.H.; Noakes, M.; Buckley, J.D.; Wittert, G.A.; Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Brinkworth, G.D. A very low-carbohydrate, low–saturated fat diet for type 2 diabetes management: A randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 2909–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, L.; Iqbal, N.; Seshadri, P.; Chicano, K.L.; Daily, D.A.; McGrory, J.; Williams, M.; Gracely, E.J.; Samaha, F.F. The effects of low-carbohydrate versus conventional weight loss diets in severely obese adults: One-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2004, 140, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westman, E.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Mavropoulos, J.C.; Marquart, M.; McDuffie, J.R. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, T.; Unwin, D.; Finucane, F. Low-Carbohydrate diets in the management of obesity and type 2 diabetes: A review from clinicians using the approach in practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.; Athinarayanan, S.; Vantieghem, M.; Mckenzie, A.; Volk, B.; Adams, R.; Fell, B.; Ratner, R.; Volek, J.; Phinney, S. 212-OR: Five-Year Follow-Up of Lipid, Inflammatory, Hepatic, and Renal Markers in People with T2 Diabetes on a Very-Low-Carbohydrate Intervention Including Nutritional Ketosis (VLCI) via Continuous Remote Care (CRC). Diabetes 2022, 71, 212-OR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athinarayanan, S.J.; Adams, R.N.; Hallberg, S.J.; McKenzie, A.L.; Bhanpuri, N.H.; Campbell, W.W.; Volek, J.S.; Phinney, S.D.; McCarter, J.P. Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of type 2 diabetes: A 2-year non-randomized clinical trial. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athinarayanan, S.J.; Vantieghem, M.; McKenzie, A.L.; Hallberg, S.; Roberts, C.G.; Volk, B.M.; Adams, R.N.; Ratner, R.E.; Volek, J.; Phinney, S. Five-Year Weight and Glycemic Outcomes following a Very-Low-Carbohydrate Intervention Including Nutritional Ketosis in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2022, 71, 832-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, A.L.; Athinarayanan, S.J.; Vantieghem, M.; Volk, B.M.; Adams, R.N.; Roberts, C.G.; Fell, B.; Ratner, R.E.; Volek, J.; Phinney, S. 59-OR: Long-Term Sustainability and Durability of Diabetes Prevention via Nutritional Intervention. Diabetes 2022, 71, 59-OR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, S48–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Fradkin, J.; Kernan, W.N.; Mathieu, C.; Mingrone, G.; Rossing, P.; Tsapas, A.; Wexler, D.J.; Buse, J.B. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2669–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diabetes. Position Statement: Low-Carb Diets for People with Diabetes; Diabetes: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kolivas, D.; Fraser, L.; Schweitzer, R.; Brukner, P.; Moschonis, G. Effectiveness of a Digitally Delivered Continuous Care Intervention (Defeat Diabetes) on Type 2 Diabetes Outcomes: A 12-Month Single-Arm, Pre–Post Intervention Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Zealand Guidelines Group. New Zealand Primary Care Handbook; New Zealand Guidelines Group: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beckingsale, L.; Fairbairn, K.; Morris, C. Integrating dietitians into primary health care: Benefits for patients, dietitians and the general practice team. J. Prim. Health Care 2016, 8, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners. The Workforce Survey 2022; Overview Report: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Healthify, Te Whatu Ora. Health Coaches. Available online: https://healthify.nz/hauora-wellbeing/h/health-coaches/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Healthify, Te Whatu Ora. Health Improvement Practitioner. Available online: https://healthify.nz/hauora-wellbeing/h/health-improvement-practitioner/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Unwin, D.; Khalid, A.A.; Unwin, J.; Crocombe, D.; Delon, C.; Martyn, K.; Golubic, R.; Ray, S. Insights from a general practice service evaluation supporting a lower carbohydrate diet in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and prediabetes: A secondary analysis of routine clinic data including HbA1c, weight and prescribing over 6 years. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2020, 3, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddy, C.; Johnston, S.; Nash, K.; Ward, N.; Irving, H. Health coaching in primary care: A feasibility model for diabetes care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.A.; Matthews, S.; Faries, M.D.; Wolever, R.Q. Supporting Sustainable Health Behavior Change: The Whole is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 8, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, L.; Martindale, R.; Salami, B.; Fakorede, F.I.; Harvey, K.; Capes, S.; Abt, G.; Chipperfield, S. Health and lifestyle advisors in support of primary care: An evaluation of an innovative pilot service in a region of high health inequality. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PreKure. Health Coach Programme. Available online: https://prekure.com/programmes/health-coach-programme/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Feinman, R.D.; Pogozelski, W.K.; Astrup, A.; Bernstein, R.K.; Fine, E.J.; Westman, E.C.; Accurso, A.; Frassetto, L.; Gower, B.A.; McFarlane, S.I. Dietary carbohydrate restriction as the first approach in diabetes management: Critical review and evidence base. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LabPLUS. Test Guide. Available online: https://testguide.adhb.govt.nz/EGuide/ (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snorgaard, O.; Poulsen, G.M.; Andersen, H.K.; Astrup, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evert, A.B.; Dennison, M.; Gardner, C.D.; Garvey, W.T.; Lau, K.H.K.; MacLeod, J.; Mitri, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Rawlings, K.; Robinson, S. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: A consensus report. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, C.; Schofield, G.; Zinn, C.; Wheldon, M.; Kraft, J. Identifying hyperinsulinaemia in the absence of impaired glucose tolerance: An examination of the Kraft database. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 118, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprou, S.; Koletsos, N.; Mintziori, G.; Anyfanti, P.; Trakatelli, C.; Kotsis, V.; Gkaliagkousi, E.; Triantafyllou, A. Microvascular and endothelial dysfunction in prediabetes. Life 2023, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, N.; Wild, S.H.; Khunti, K.; Knighton, P.; O’Keefe, J.; Bakhai, C.; Young, B.; Sattar, N.; Valabhji, J.; Gregg, E.W. Incidence and characteristics of remission of type 2 diabetes in England: A cohort study using the National Diabetes Audit. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quimby, K.R. Evaluation of a type 2 diabetes remission programme. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkelund, S.I. Serum alanine aminotransferase activity and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in a Caucasian population: The Tromsø study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.S. Seasonal variations of selected cardiovascular risk factors. Altern. Med. Rev. 2005, 10, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boizel, R.; Benhamou, P.Y.; Lardy, B.; Laporte, F.; Foulon, T.; Halimi, S. Ratio of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol is an indicator of LDL particle size in patients with type 2 diabetes and normal HDL cholesterol levels. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 1679–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luz, P.L.d.; Favarato, D.; Faria-Neto Junior, J.R.; Lemos, P.; Chagas, A.C.P. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics 2008, 63, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinn, C.; Campbell, J.L.; Po, M.; Sa’ulilo, L.; Fraser, L.; Davies, G.; Hawkins, M.; Currie, O.; Unwin, D.; Crofts, C. Redefining Diabetes Care: Evaluating the Impact of a Carbohydrate-Reduction, Health Coach Approach Model in New Zealand. J. Diabetes Res. 2024, 2024, 4843889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.L.; Elliott, J.E.; Rao, S.M.; Fahey, K.F.; Paul, S.M.; Miaskowski, C. A randomized clinical trial of education- or motivational interviewing–based coaching compared with usual care to improve cancer pain management. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2012, 39, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, M.J.; Jelinek, M.V.; Best, J.D.; Dart, A.M.; Grigg, L.E.; Hare, D.L.; Ho, B.P.; Newman, R.W.; McNeil, J.J. Coaching patients On Achieving Cardiovascular Health (COACH): A multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Wulp, I.; De Leeuw, J.; Gorter, K.; Rutten, G. Effectiveness of peer-led self-management coaching for patients recently diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Diabet. Med. 2012, 29, e390–e397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolever, R.; Dreusicke, M.; Fikkan, J.; Hawkins, T.; Yeung, S.; Wakefield, J.; Duda, L.; Flowers, P.; Cook, C.; Skinner, E. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signal, V.; McLeod, M.; Stanley, J.; Stairmand, J.; Sukumaran, N.; Thompson, D.-M.; Henderson, K.; Davies, C.; Krebs, J.; Dowell, A. A Mobile-and web-based health intervention program for diabetes and prediabetes self-management (BetaMe/Melon): Process evaluation following a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Mustafa, S.T.; Cassim, S.; Mullins, H.; Clark, P.; Keenan, R.; Te Karu, L.; Murphy, R.; Paul, R.; Kenealy, T. General practitioner and nurse experiences of type 2 diabetes management and prescribing in primary care: A qualitative review following the introduction of funded SGLT2i/GLP1RA medications in Aotearoa New Zealand. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2024, 25, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, A.J.; Nordmann, A.; Briel, M.; Keller, U.; Yancy, W.S.; Brehm, B.J.; Bucher, H.C. Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998, 352, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Practice 1 | Practice 2 | Practice 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Weigh | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Blood pressure | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lipids | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Renal function | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Liver function | ✓ | ✓ |

| Practice 1 | Practice 2 | Practice 3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n, %) | 46 (43%) | 41 (39%) | 19 (18%) | 106 |

| Female (%) | 61 | 40 | 63 | 53 |

| Male (%) | 39 | 60 | 37 | 47 |

| Ethnicity | 52% Māori, 41% Pacific Island | 89% European | 73% European | - |

| Mean Age (years ± SD) | 46.4 ± 11.3 | 70 ± 16.0 | 54.5 ± 10.5 | 54.0 ± 17.0 |

| Median Follow-up Duration (months, IQR) | 38 (13–50) | 19 (8–23) | 5 (3–9) | 19 (6–32) |

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n = 103, all practices) | |||

| Age (years) | −0.14 | −0.34, 0.06 | 0.154 |

| Follow-up duration (days) | <0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0.095 |

| Baseline HbA1c (mmol/mol) | −0.37 | −0.51, −0.24 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European | — | — | |

| Māori or Pacific | −5.62 | −13.27, 2.02 | 0.148 |

| Other * | −12.54 | −20.99, −4.10 | 0.004 |

| Model 2 (n = 75, Practice 1 and 2) | |||

| Age (years) | −0.08 | −0.33, 0.14 | 0.498 |

| Follow-up duration (days) | 0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0.011 |

| Baseline HbA1c (mmol/mol) | −0.32 | −0.51, −0.24 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European | — | — | |

| Māori or Pacific | −0.88 | −10.17, 8.42 | 0.851 |

| Other * | −14.39 | −28.86, 0.08 | 0.051 |

| Change in weight (Kg) | 0.56 | 0.30, 0.83 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 (n = 51, Practice 1 and 3) | |||

| Age (years) | −0.23 | −0.66, 0.20 | 0.467 |

| Follow-up duration (days) | <0.01 | −0.01, 0.01 | 0.142 |

| Baseline HbA1c (mmol/mol) | −0.44 | −0.68, −0.21 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European | — | — | |

| Māori or Pacific | −26.00 | −62.87, 10.87 | 0.162 |

| Other * | −36.18 | −76.76, 4.40 | 0.079 |

| Engagement | |||

| Yes | — | — | |

| No | 3.42 | −7.64, 14.48 | 0.536 |

| Number of doctor’s visits (n) | 0.07 | −0.31, 0.46 | 0.698 |

| Frequency initial period (times/month) | −0.94 | −2.11, 0.23 | 0.113 |

| Variable | Baseline | Last Follow-Up | Change | Matched Pairs | r | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 99 (83, 115) | 94 (78, 113) | −3 (−8, 0) | 77 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 51 (42, 65) | 47 (41, 49) | −3 (−7, 3) | 103 | 0.28 | 0.005 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135 (120, 150) | 130 (120, 140) | −3 (−20, 12) | 83 | 0.20 | 0.074 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 80 (70, 88) | 79 (70, 88) | 0 (−4, 0) | 83 | 0.17 | 0.148 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.20 (4.40, 6.10) | 5.00 (4.20, 6.40) | 0.05 (−0.63, 0.43) | 49 | 0.01 | 0.943 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 2.09 (1.38, 3.20) | 1.85 (1.30, 2.90) | 0.01 (−0.90, 0.42) | 48 | 0.06 | 0.680 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.10 (0.92, 1.26) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.22) | −0.11 (−0.21, 0.07) | 49 | 0.31 | 0.029 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.90 (2.30, 3.90) | 2.90 (2.40, 3.75) | 0.00 (−0.45, 0.48) | 42 | 0.07 | 0.640 |

| TG:HDL radio | 1.69 (1.06, 3.36) | 1.65 (1.13, 3.39) | 0.03 (−0.85, 0.89)) | 48 | 0.01 | 0.947 |

| ALP (u/L) | 79 (46, 102) | 74 (57, 89) | −1 (−16, 11) | 46 | 0.04 | 0.748 |

| GGT | 35 (26, 58) | 33 (21, 57) | −4 (−15, 18) | 46 | 0.03 | 0.870 |

| ALT | 33 (22, 52) | 23 (18, 37) | −10 (−20, −1) | 42 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 67 (60, 85) | 66 (58, 82) | −2 (−7, 7) | 42 | 0.06 | 0.726 |

| Uric acid (mmol/L) | 0.37 (0.33, 0.40) | 0.38 (0.34, 0.41) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | 16 | 0.21 | 0.379 |

| Albumin-to-creatinine ratio | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.24) | 16 | 0.22 | 0.505 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zinn, C.; Campbell, J.L.; Fraser, L.; Davies, G.; Hawkins, M.; Currie, O.; Cannons, J.; Unwin, D.; Crofts, C.; Stewart, T.; et al. Carbohydrate Reduction and a Holistic Model of Care in Diabetes Management: Insights from a Retrospective Multi-Year Audit in New Zealand. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243953

Zinn C, Campbell JL, Fraser L, Davies G, Hawkins M, Currie O, Cannons J, Unwin D, Crofts C, Stewart T, et al. Carbohydrate Reduction and a Holistic Model of Care in Diabetes Management: Insights from a Retrospective Multi-Year Audit in New Zealand. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243953

Chicago/Turabian StyleZinn, Caryn, Jessica L. Campbell, Lily Fraser, Glen Davies, Marcus Hawkins, Olivia Currie, Jared Cannons, David Unwin, Catherine Crofts, Tom Stewart, and et al. 2025. "Carbohydrate Reduction and a Holistic Model of Care in Diabetes Management: Insights from a Retrospective Multi-Year Audit in New Zealand" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243953

APA StyleZinn, C., Campbell, J. L., Fraser, L., Davies, G., Hawkins, M., Currie, O., Cannons, J., Unwin, D., Crofts, C., Stewart, T., & Schofield, G. (2025). Carbohydrate Reduction and a Holistic Model of Care in Diabetes Management: Insights from a Retrospective Multi-Year Audit in New Zealand. Nutrients, 17(24), 3953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243953