Dietary Supplement Interventions and Sleep Quality Improvement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. GRADE Assessment

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

3.2. Study Characteristics and Individual Outcomes

3.3. Risk of Bias, Publication Bias, and Certainty Assessment

3.4. Meta-Analysis Results

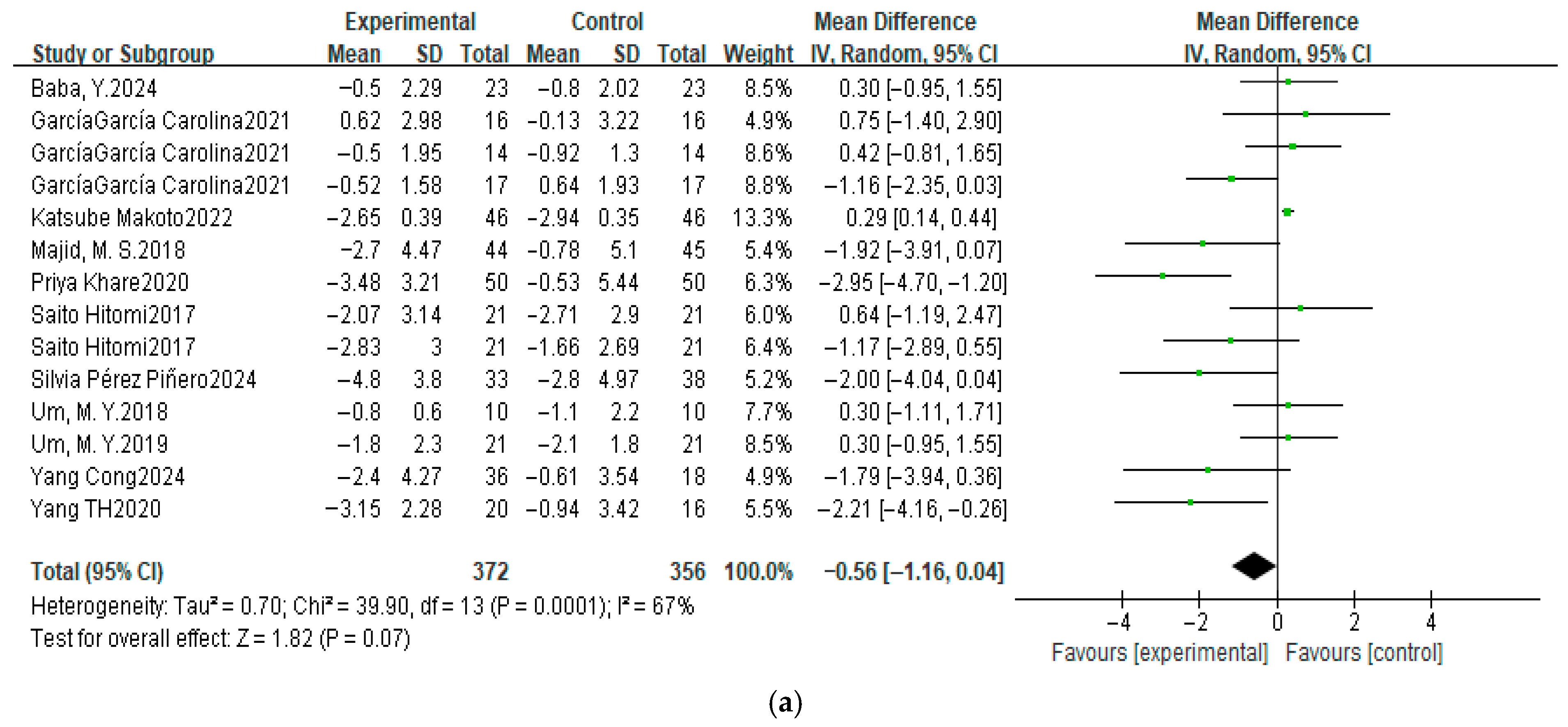

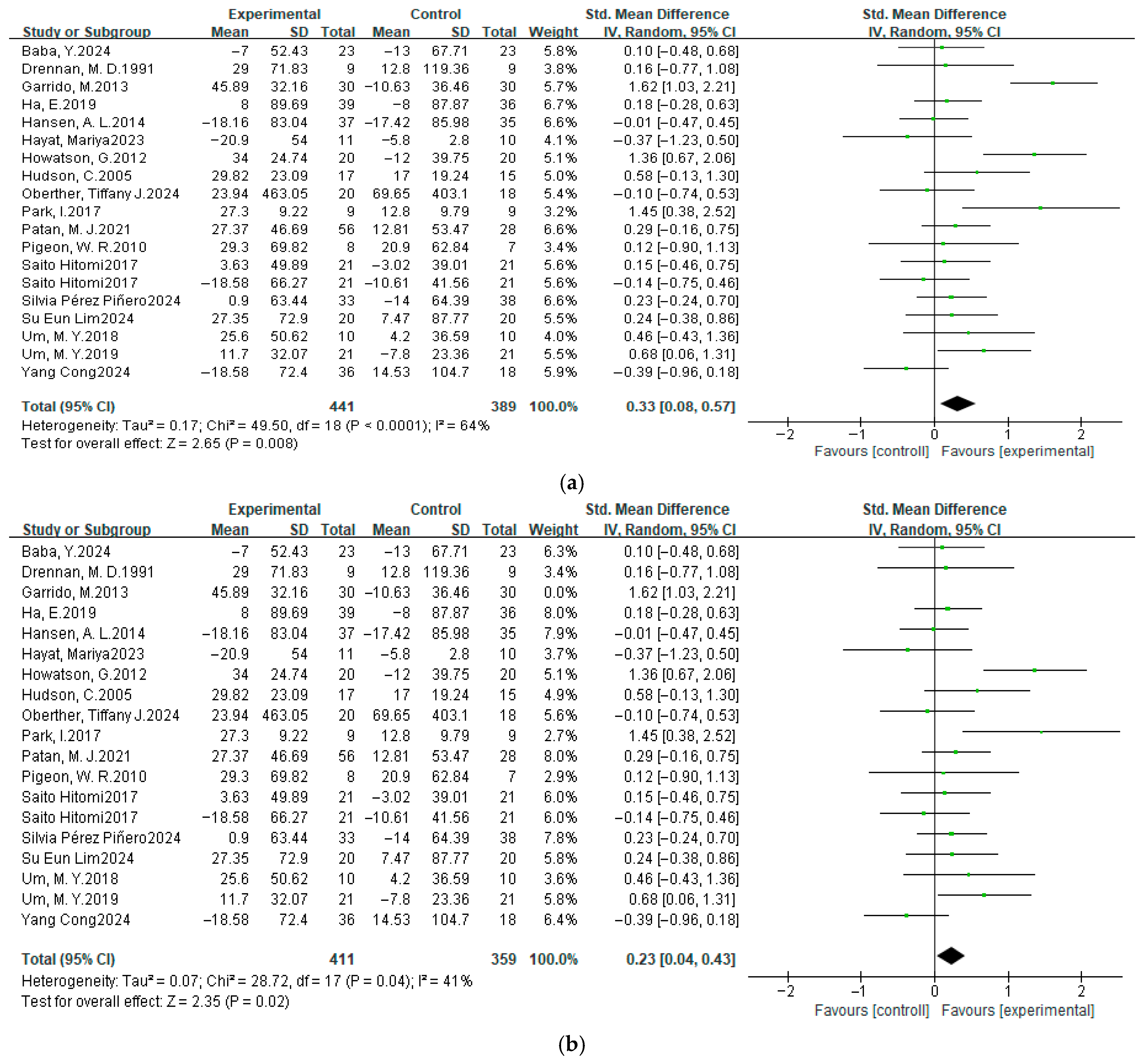

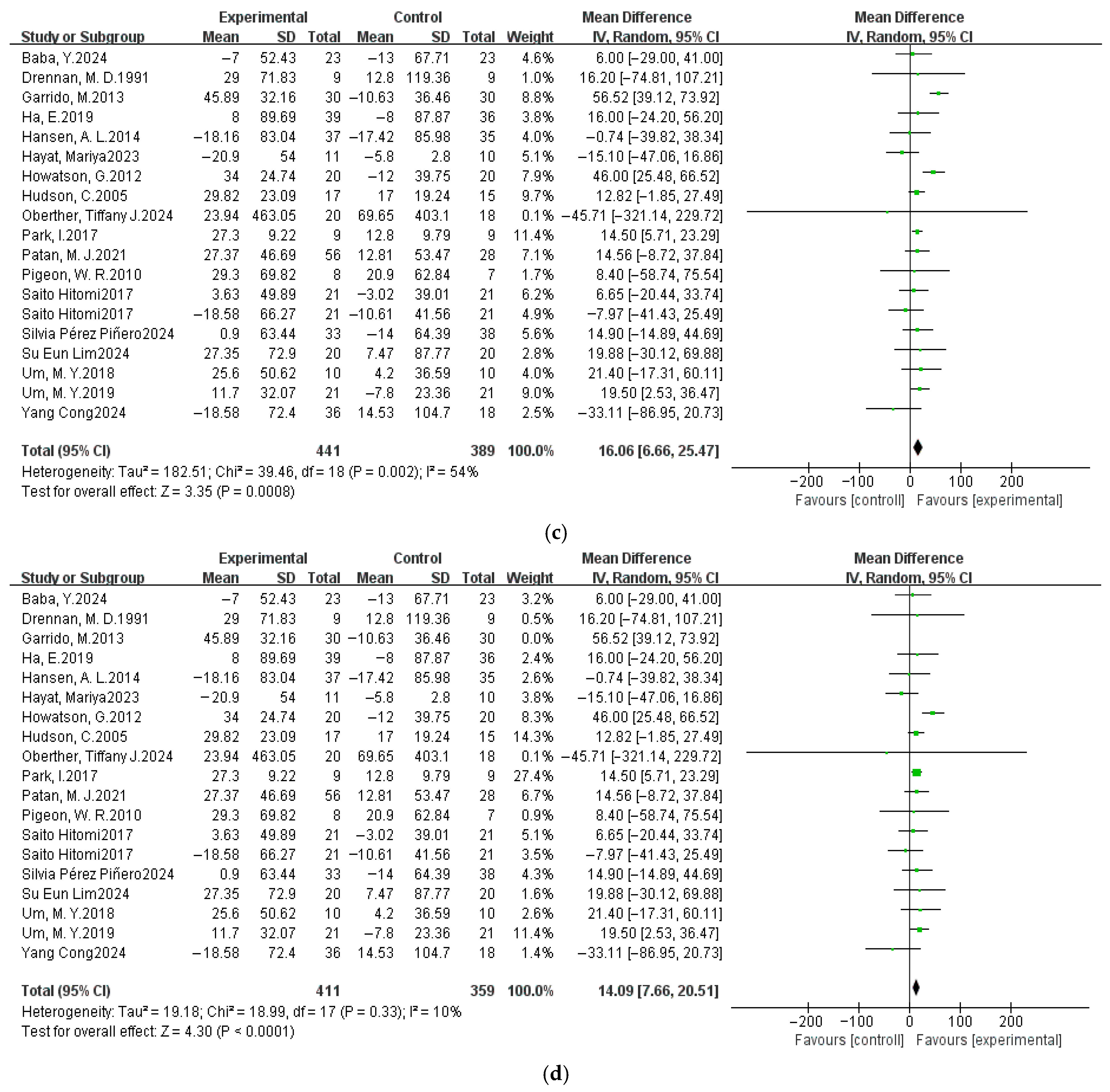

3.4.1. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

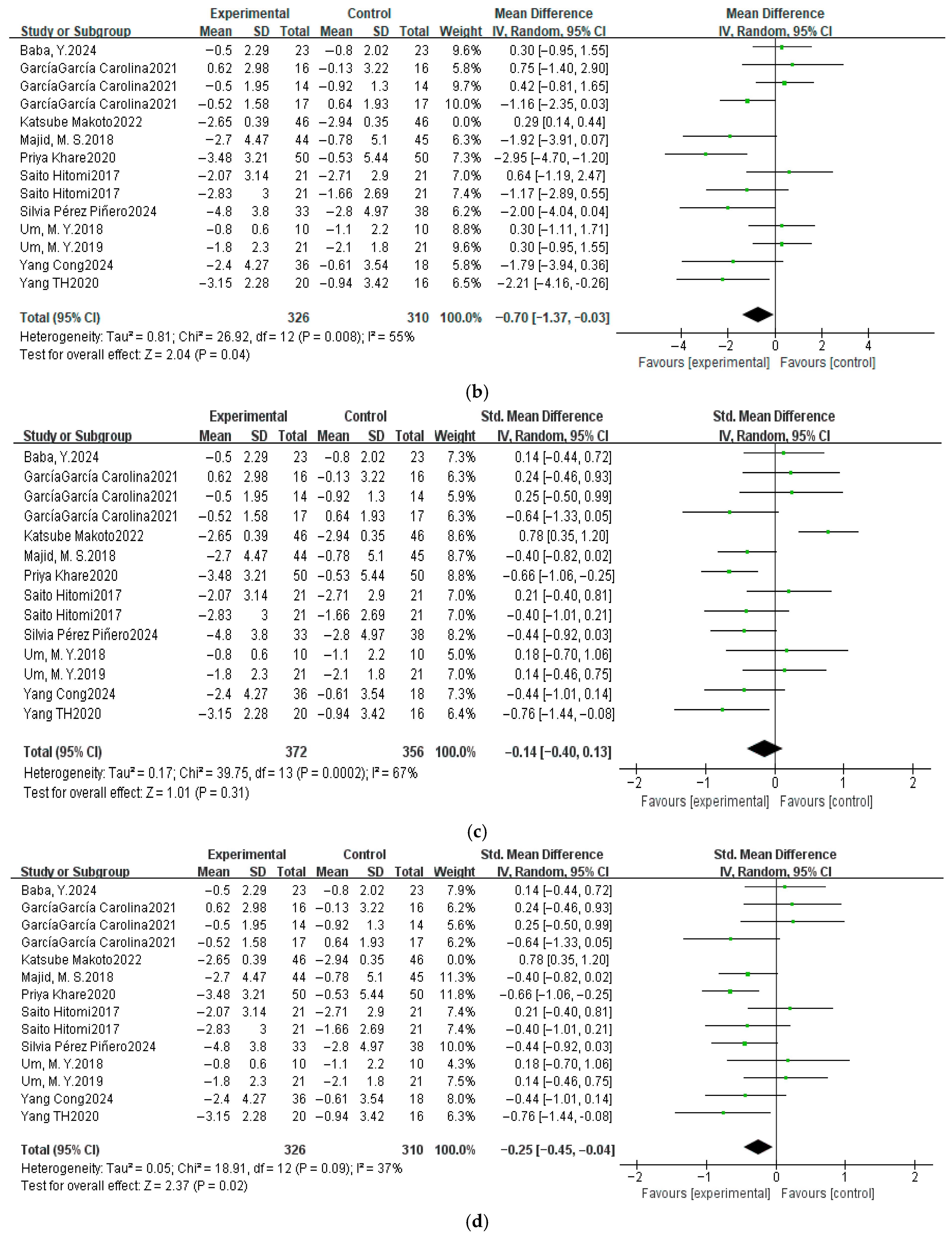

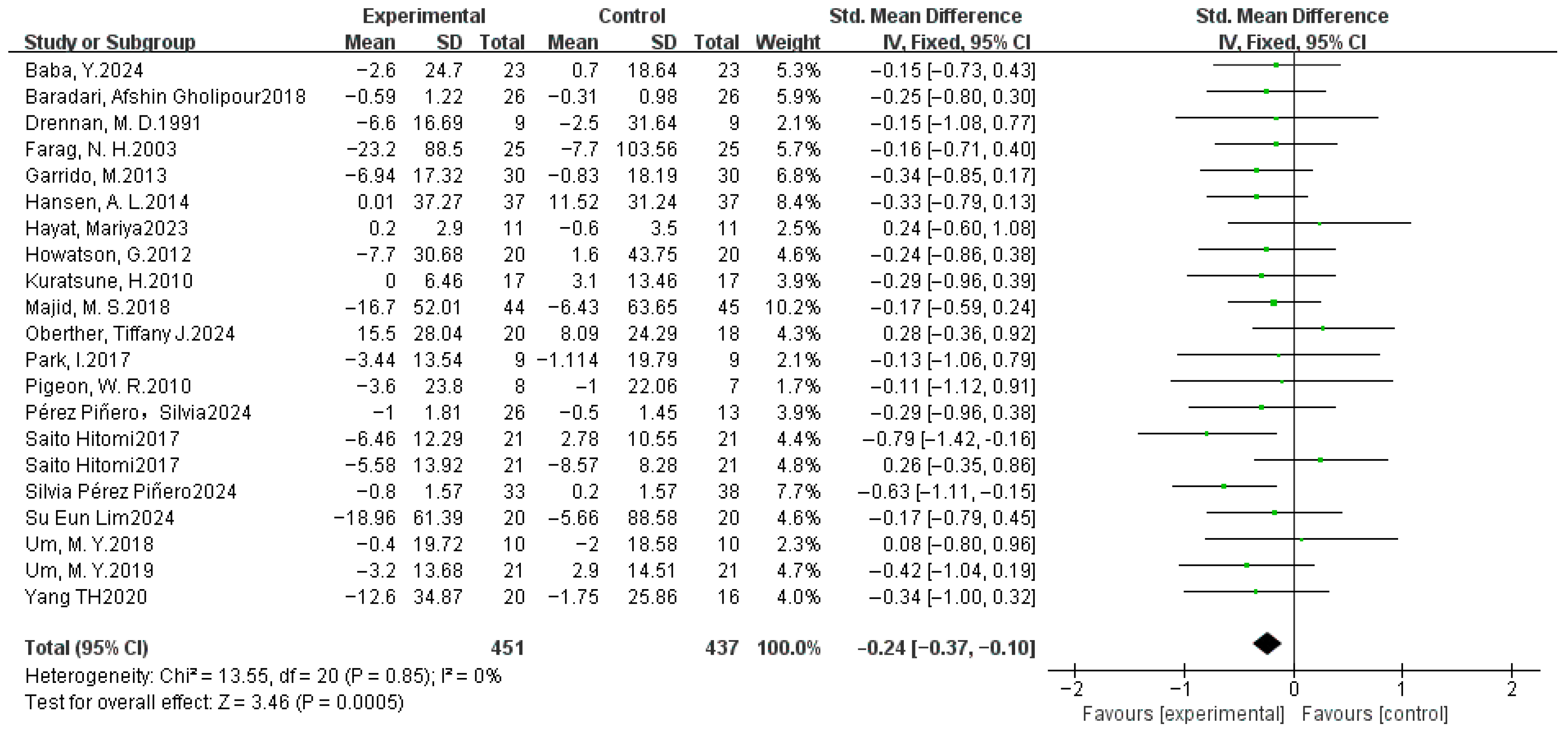

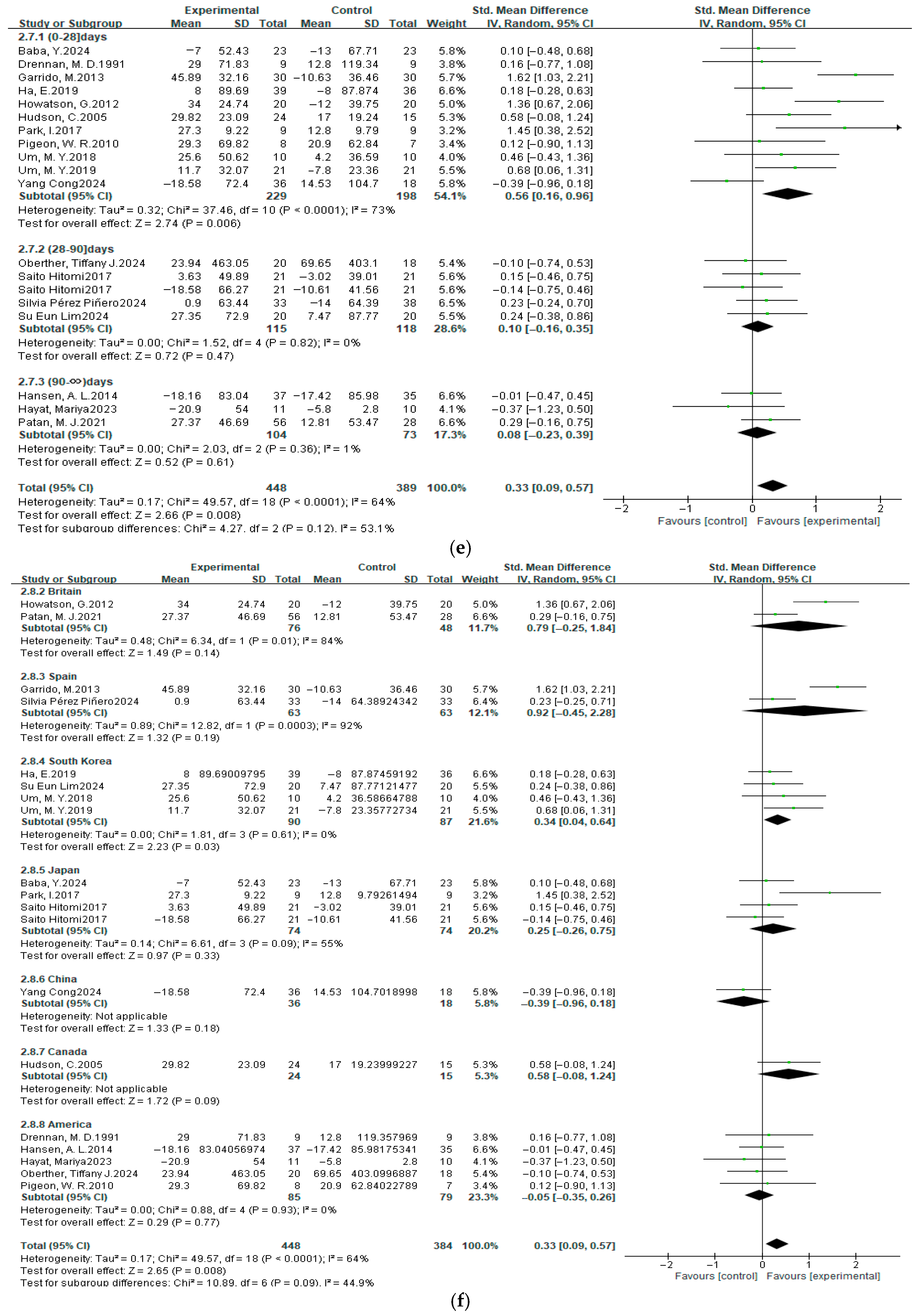

3.4.2. Sleep Efficiency

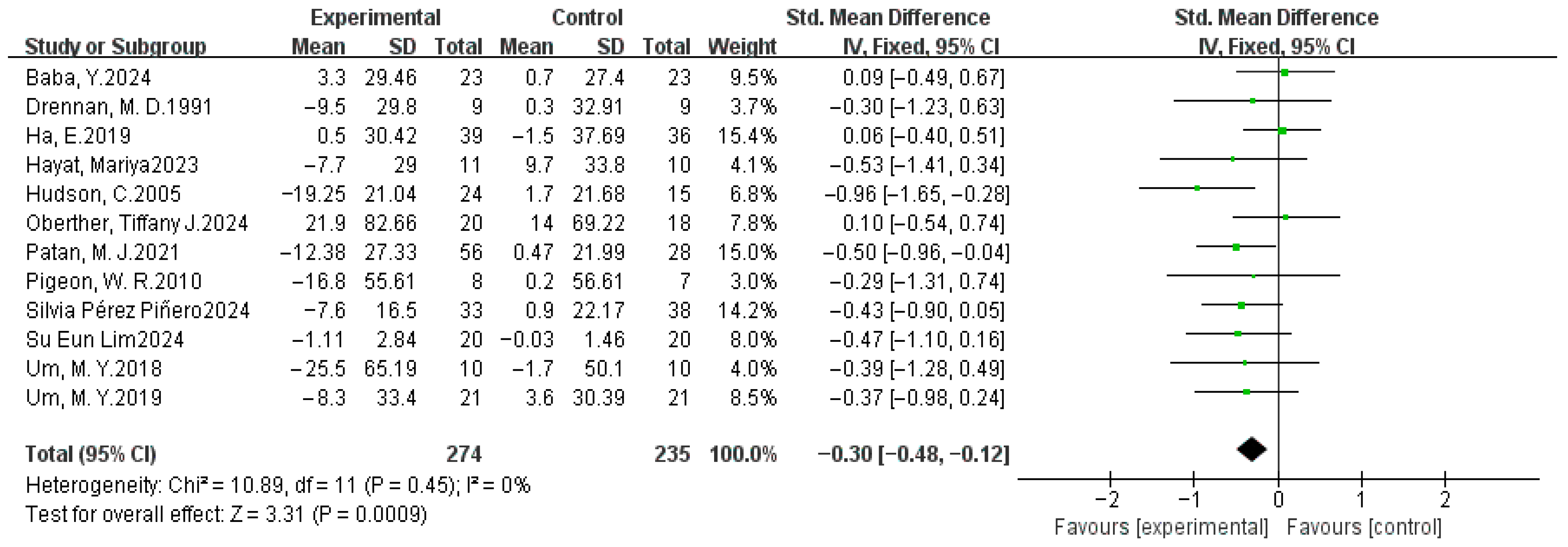

3.4.3. Total Sleep Time

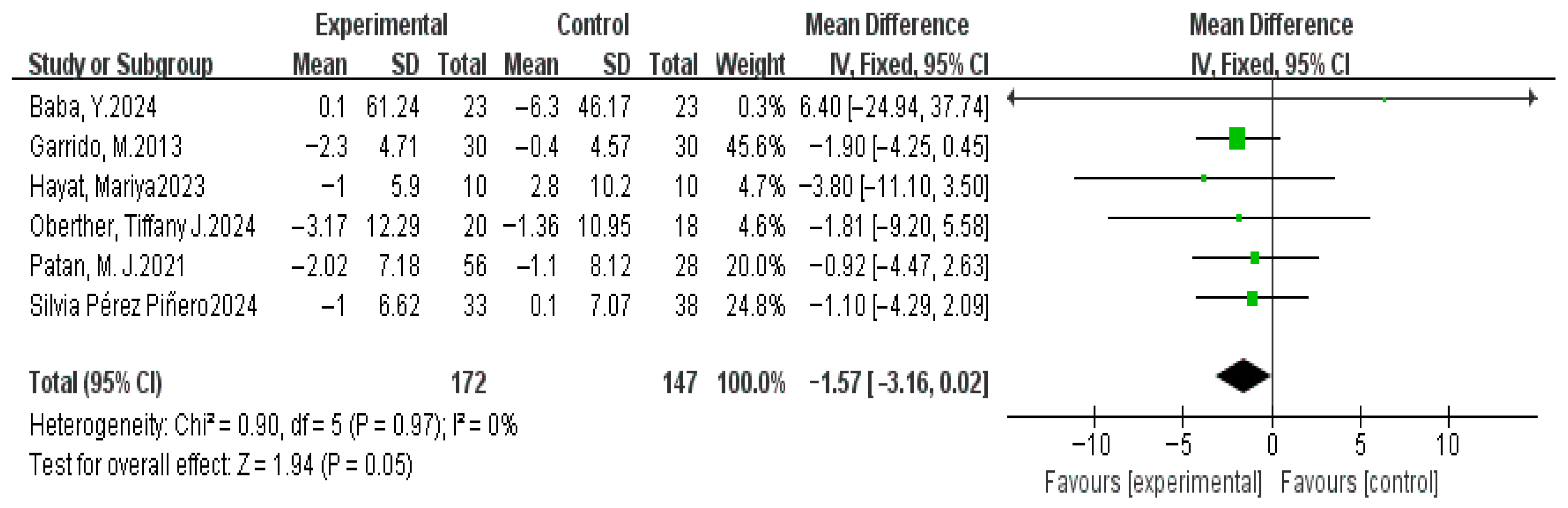

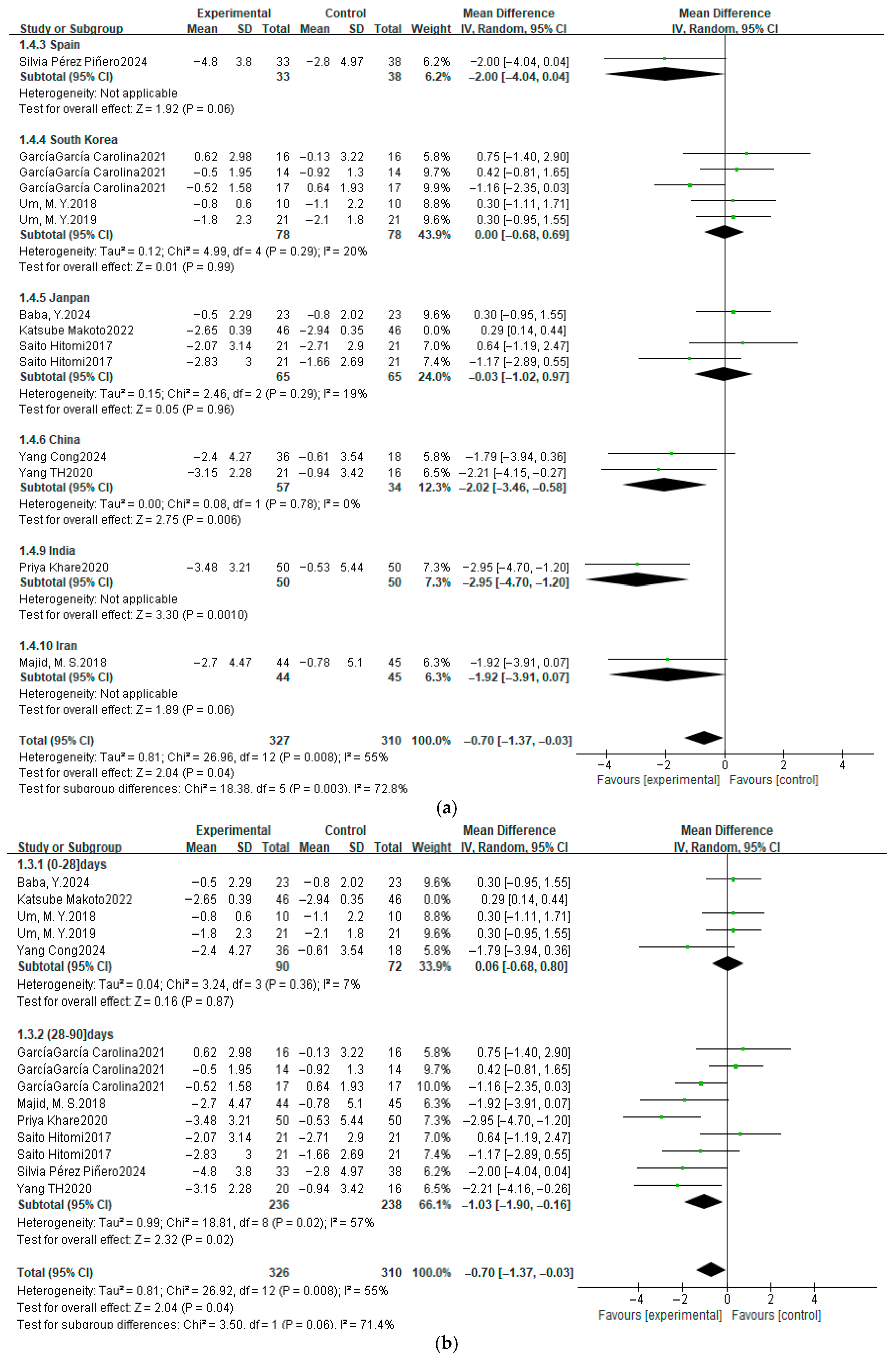

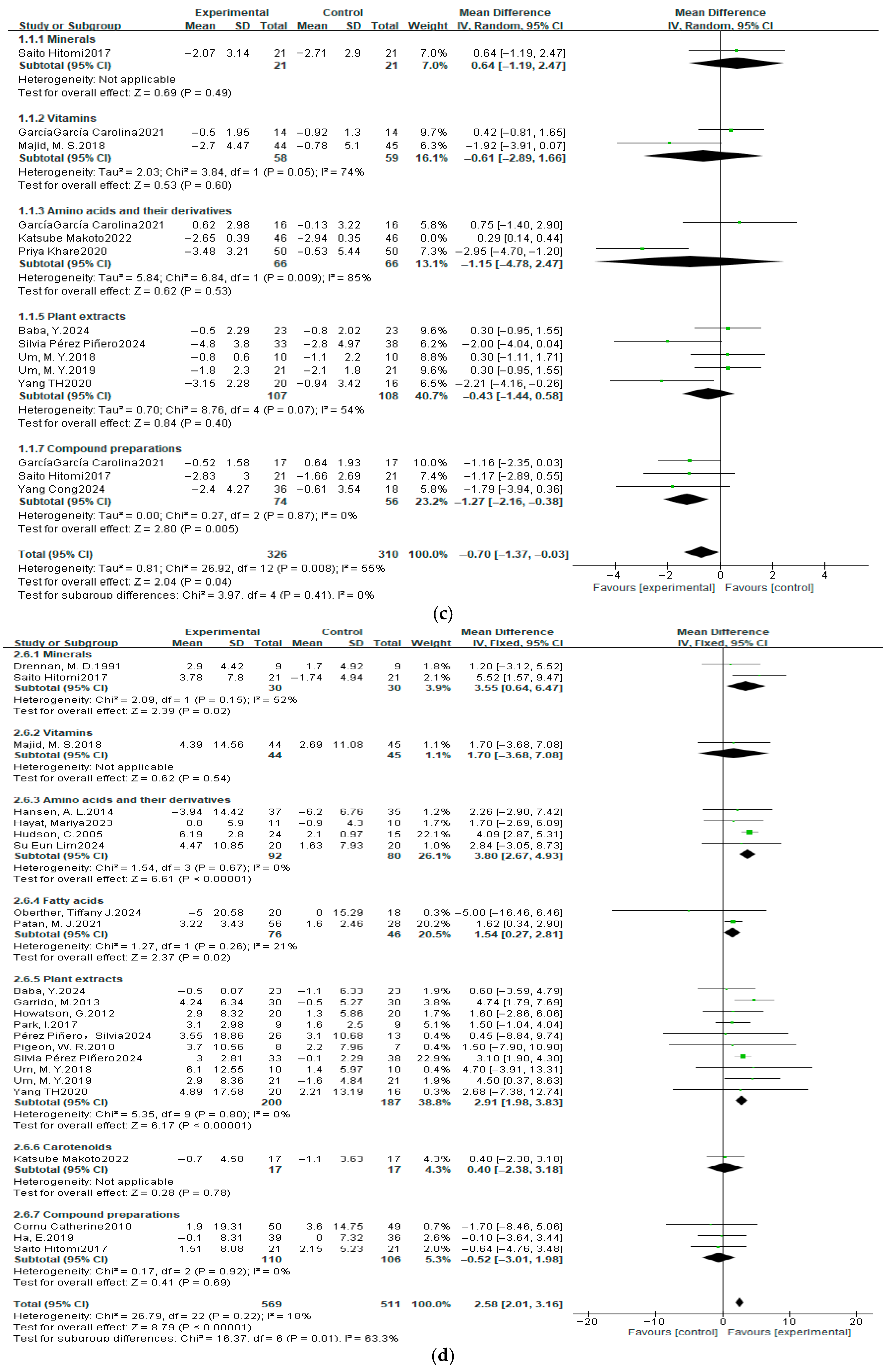

3.4.4. Sleep Latency

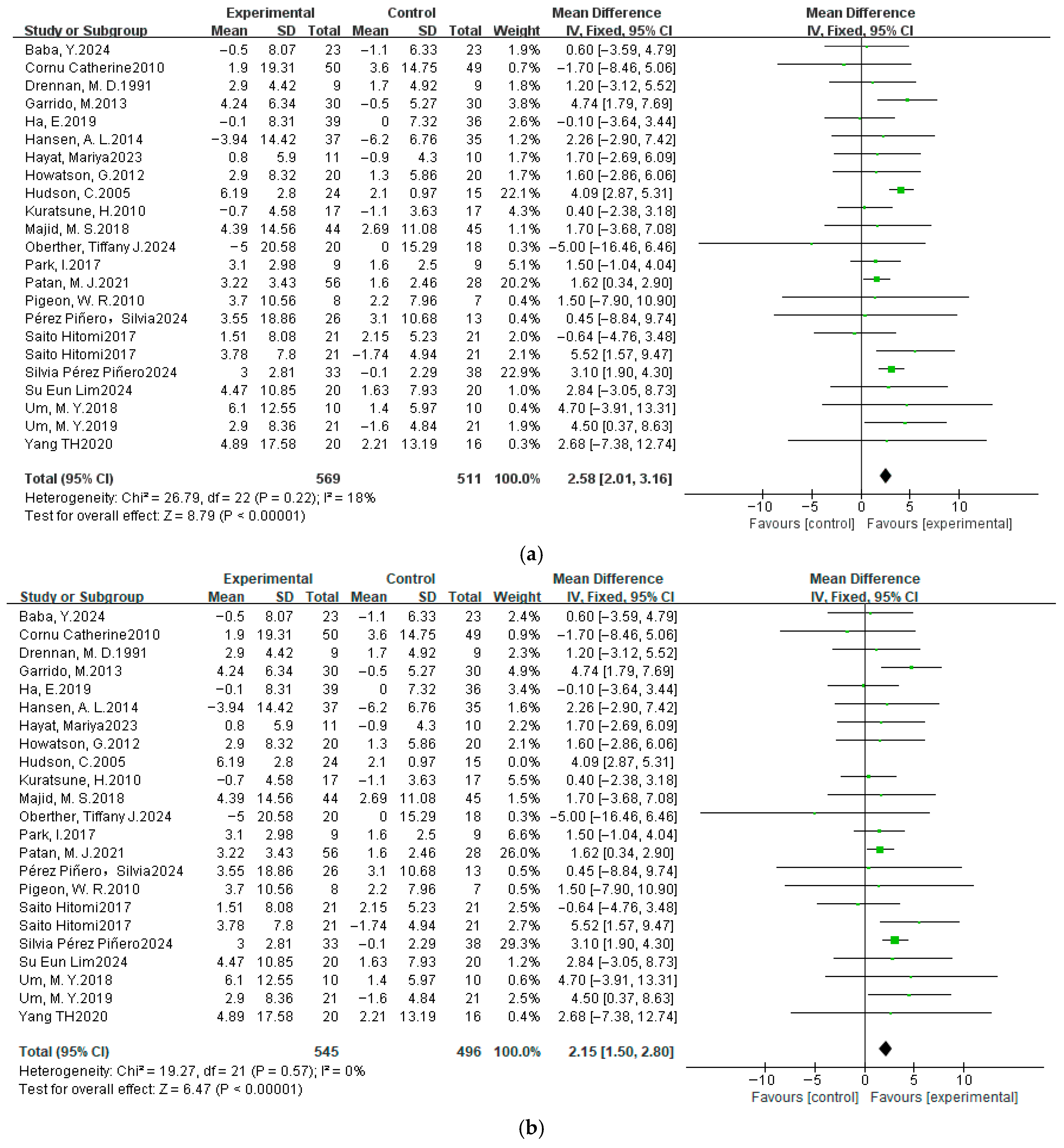

3.4.5. Wake After Sleep Onset

3.4.6. Number of Awake After Sleep Onset

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

3.6. Meta-Regression

3.7. Subgroup Analysis

3.8. GRADE Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Weaknesses

6. Conclusions

- Amino acid (e.g., Tryptophan) and vitamin (vitamin D) sources.

- n-3 PUFAs.

- Essential minerals (e.g., zinc).

- Antioxidant-rich dietary components.

- Nutrient precision—strict monitoring of supplementation dosage.

- Lifestyle integration—synergistic dietary adjustments.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| SE | Sleep efficiency |

| TST | Total sleep time |

| SL | Sleep latency |

| WASO | Wake after sleep onset |

| NASO | Number of awake after sleep onset |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| CBT-I | Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia |

| M | Mean |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| MD diff | Changes in mean |

| SD diff | Changes in standard deviation |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| r | Correlation coefficient |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| min | Minutes |

| MT | Melatonin |

| NREM | Non-rapid eye movement |

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptophan |

| NAT | N-acetyltransferase |

| SNAT | Serotonin N-acetyltransferase |

| ASMT | Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase |

| SCN | Hypothalamic-suprachiasmatic nucleus |

| TPH2 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 2 |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

References

- AASM. International Classification of Sleep Disorders; American Academy of Sleep Medicine–Association for Sleep Clinicians and Researchers: Darien, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leger, D.; Beck, F.; Richard, J.-B.; Godeau, E. Total Sleep Time Severely Drops during Adolescence. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet Diabetes Endocrinology. Sleep: A Neglected Public Health Issue. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 365. [CrossRef]

- Butris, N.; Tang, E.; Pivetta, B.; He, D.; Saripella, A.; Yan, E.; Englesakis, M.; Boulos, M.I.; Nagappa, M.; Chung, F. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sleep Disturbances in Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 69, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, R.M.; Blask, D.E.; Coogan, A.N.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gorman, M.R.; Hall, J.E.; Hansen, J.; Nelson, R.J.; Panda, S.; Smolensky, M.H.; et al. Health Consequences of Electric Lighting Practices in the Modern World: A Report on the National Toxicology Program’s Workshop on Shift Work at Night, Artificial Light at Night, and Circadian Disruption. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.; Smith, R.B.; Bou Karim, Y.; Shen, C.; Drummond, K.; Teng, C.; Toledano, M.B. Noise Pollution and Human Cognition: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Evidence. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. Perceived Stress and Internet Addiction among Chinese College Students: Mediating Effect of Procrastination and Moderating Effect of Flow. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopheide, J.A. Insomnia Overview: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Monitoring, and Nonpharmacologic Therapy. Am. J. Manag. Care 2020, 26, S76–S84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perlis, M.L.; Posner, D.; Riemann, D.; Bastien, C.H.; Teel, J.; Thase, M. Insomnia. Lancet 2022, 400, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillehei, A.S.; Halcón, L.L.; Savik, K.; Reis, R. Effect of Inhaled Lavender and Sleep Hygiene on Self-Reported Sleep Issues: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2015, 21, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.S.; Rabin, L.A. Sleep America: Managing the Crisis of Adult Chronic Insomnia and Associated Conditions. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 192–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaseem, A.; Kansagara, D.; Forciea, M.A.; Cooke, M.; Denberg, T.D. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbricht, A.; Velez, M.L. Benzodiazepine and Nonbenzodiazepine Hypnotics (Z-Drugs): The Other Epidemic. In Textbook of Addiction Treatment: International Perspectives; el-Guebaly, N., Carrà, G., Galanter, M., Baldacchino, A.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 141–156. ISBN 978-3-030-36391-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Hallt, E.; Platz, A.; Humblet, A.; Lassig-Smith, M.; Stuart, J.; Fourie, C.; Livermore, A.; McConnochie, B.-Y.; Starr, T.; et al. Low-Dose Clonidine Infusion to Improve Sleep in Postoperative Patients in the High-Dependency Unit. A Randomised Placebo-Controlled Single-Centre Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2024, 50, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanji, S.; Mera, A.; Hutton, B.; Burry, L.; Rosenberg, E.; MacDonald, E.; Luks, V. Pharmacological Interventions to Improve Sleep in Hospitalised Adults: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebipour, M.R.; Joghataei, M.T.; Yoonessi, A.; Sadeghniiat-Haghighi, K.; Khalighinejad, N.; Khademi, S. Slow Oscillating Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation during Sleep Has a Sleep-Stabilizing Effect in Chronic Insomnia: A Pilot Study. J. Sleep Res. 2015, 24, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffel, E.A.; Koffel, J.B.; Gehrman, P.R. A Meta-Analysis of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 19, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Lang, Y.; Lin, L.; Yang, X.-J.; Jiang, X.-J. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (ICBT-i) Improves Comorbid Anxiety and Depression—A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger-Brown, J.M.; Rogers, V.E.; Liu, W.; Ludeman, E.M.; Downton, K.D.; Diaz-Abad, M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Persons with Comorbid Insomnia: A Meta-Analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2015, 23, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Scherffius, A.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Q.-W.; Wang, D. Bidirectional Associations between Insomnia Symptoms and Eating Disorders: A Two-Wave Longitudinal Study among Chinese College Students. Eat. Behav. 2025, 56, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Grosso, G.; Castellano, S.; Galvano, F.; Caraci, F.; Ferri, R. Association between Diet and Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 57, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Fostitsch, A.J.; Schwarzer, G.; Buchgeister, M.; Surbeck, W.; Lahmann, C.; Spiegelhalder, K.; Frase, L.; Spieler, D. The Association between Sleep Quality and Telomere Attrition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Comprising 400,212 Participants. Sleep Med. Rev. 2025, 80, 102073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wan, Q.; Yu, F. Comparative Efficacy of Various Exercise Interventions on Cognitive Function in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Stewart, S.A.; Bagg, M.K.; Stanojevic, S.; Yamato, T.P.; Saragiotto, B.T. Some Types of Exercise Are More Effective than Others in People with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Network Meta-Analysis. J. Physiother. 2021, 67, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutanto, C.N.; Loh, W.W.; Kim, J.E. The Impact of Tryptophan Supplementation on Sleep Quality: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandell, A.; Giles, L.; Cervelo Bouzo, P.; Sibbring, G.C.; Maniaci, J.; Wojtczak, H.; Sokolow, A.G. Safety of LAIV Vaccination in Asthma or Wheeze: A Systematic Review and GRADE Assessment. Pediatrics 2025, 155, e2024068459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. xv, 377. ISBN 978-1-60623-639-0. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.R.; Bartlett, J.W.; Morris, T.P.; Wood, A.M.; Quartagno, M.; Kenward, M.G. Multiple Imputation of Quantitative Data. In Multiple Imputation and Its Application; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 75–89. ISBN 978-1-119-94228-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.A.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated Guidance for Trusted Systematic Reviews: A New Edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochrane Colloquium Abstracts. The Selection of Fixed- or Random-Effect Models in Recent Published Meta-Analyses. Available online: https://abstracts.cochrane.org/2015-vienna/selection-fixed-or-random-effect-models-recent-published-meta-analyses (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappuccio, F.P.; D’Elia, L.; Strazzullo, P.; Miller, M.A. Sleep Duration and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Sleep 2010, 33, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubu, O.M.; Brannick, M.; Mortimer, J.; Umasabor-Bubu, O.; Sebastião, Y.V.; Wen, Y.; Schwartz, S.; Borenstein, A.R.; Wu, Y.; Morgan, D.; et al. Sleep, Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sleep 2017, 40, zsw032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and Eating Behaviours in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, Y.; Takihara, T.; Okamura, N. Matcha Does Not Affect Electroencephalography during Sleep but May Enhance Mental Well-Being: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipour Baradari, A.; Alipour, A.; Mahdavi, A.; Sharifi, H.; Nouraei, S.M.; Emami Zeydi, A. The Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Sleep Quality of ICU Nurses: A Double Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Workplace Health Saf. 2018, 66, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, C.; Baik, I. Effects of Poly-Gamma-Glutamic Acid and Vitamin B6 Supplements on Sleep Status: A Randomized Intervention Study. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornu, C.; Remontet, L.; Noel-Baron, F.; Nicolas, A.; Feugier-Favier, N.; Roy, P.; Claustrat, B.; Saadatian-Elahi, M.; Kassaï, B. A Dietary Supplement to Improve the Quality of Sleep: A Randomized Placebo Controlled Trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Xu, H. Oral Nutritional Dietary Supplement Containing GABA and Asparagus Powder Improves Sleep. Int. J. Biol. Life Sci. 2024, 6, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, M.D.; Kripke, D.F.; Klemfuss, H.A.; Moore, J.D. Potassium Affects Actigraph-Identified Sleep. Sleep 1991, 14, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, N.H.; Mills, P.J. A Randomised-Controlled Trial of the Effects of a Traditional Herbal Supplement on Sleep Onset Insomnia. Complement. Ther. Med. 2003, 11, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, M.; González-Gómez, D.; Lozano, M.; Barriga, C.; Paredes, S.D.; Rodríguez, A.B. A Jerte Valley Cherry Product Provides Beneficial Effects on Sleep Quality. Influence on Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, E.; Hong, H.; Kim, T.D.; Hong, G.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, N.; Jeon, S.D.; Ahn, C.-W.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Efficacy of Polygonatum Sibiricum on Mild Insomnia: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.L.; Dahl, L.; Olson, G.; Thornton, D.; Graff, I.E.; Frøyland, L.; Thayer, J.F.; Pallesen, S. Fish Consumption, Sleep, Daily Functioning, and Heart Rate Variability. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2014, 10, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M. The Effect of Carbohydrate Source as Part of a High Protein, Weight-Maintenance Diet on Outcomes of Well-Being in Adults at Risk for Metabolic Syndrome. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, H.; Cherasse, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Mitarai, M.; Ueda, F.; Urade, Y. Zinc-Rich Oysters as Well as Zinc-Yeast- and Astaxanthin-Enriched Food Improved Sleep Efficiency and Sleep Onset in a Randomized Controlled Trial of Healthy Individuals. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howatson, G.; Bell, P.G.; Tallent, J.; Middleton, B.; McHugh, M.P.; Ellis, J. Effect of Tart Cherry Juice (Prunus cerasus) on Melatonin Levels and Enhanced Sleep Quality. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, C.; Hudson, S.P.; Hecht, T.; MacKenzie, J. Protein Source Tryptophan versus Pharmaceutical Grade Tryptophan as an Efficacious Treatment for Chronic Insomnia. Nutr. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khare, P.; Kulkarni, O.; Agrawal, A.; Ganu, G.; Joshi, M.; Sisode, M. Randomized Control Trial to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of NRL/2019/5PNW with Micronutrient Fortification to Promote Health and Well-Being in Woman in Fertile Age. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2020, 10, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratsune, H.; Umigai, N.; Takeno, R.; Kajimoto, Y.; Nakano, T. Effect of Crocetin from Gardenia Jasminoides Ellis on Sleep: A Pilot Study. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 840–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.E.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.; Kang, E.Y.; Lim, J.-H.; Kim, B.-Y.; Shin, S.-M.; Baek, Y. Dietary Supplementation with Lactium and L-Theanine Alleviates Sleep Disturbance in Adults: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1419978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.S.; Ahmad, H.S.; Bizhan, H.; Hosein, H.Z.M.; Mohammad, A. The Effect of Vitamin D Supplement on the Score and Quality of Sleep in 20-50 Year-Old People with Sleep Disorders Compared with Control Group. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsube, M.; Watanabe, H.; Suzuki, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Tatebayashi, Y.; Kato, Y.; Murayama, N. Food-Derived Antioxidant Ergothioneine Improves Sleep Difficulties in Humans. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 95, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-H.; Chen, Y.C.; Ou, T.-H.; Chien, Y.-W. Dietary Supplement of Tomato Can Accelerate Urinary aMT6s Level and Improve Sleep Quality in Obese Postmenopausal Women. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberther, T.J.; Moore, A.R.; Kohler, A.A.; Shuler, D.H.; Peritore, N.; Holland-Winkler, A.M. Effect of Peanut Butter Intake on Sleep Health in Firefighters: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Ochiai, R.; Ogata, H.; Kayaba, M.; Hari, S.; Hibi, M.; Katsuragi, Y.; Satoh, M.; Tokuyama, K. Effects of Subacute Ingestion of Chlorogenic Acids on Sleep Architecture and Energy Metabolism through Activity of the Autonomic Nervous System: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blinded Cross-over Trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patan, M.J.; Kennedy, D.O.; Husberg, C.; Hustvedt, S.O.; Calder, P.C.; Middleton, B.; Khan, J.; Forster, J.; Jackson, P.A. Differential Effects of DHA- and EPA-Rich Oils on Sleep in Healthy Young Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigeon, W.R.; Carr, M.; Gorman, C.; Perlis, M.L. Effects of a Tart Cherry Juice Beverage on the Sleep of Older Adults with Insomnia: A Pilot Study. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Piñero, S.; Muñoz-Carrillo, J.C.; Echepare-Taberna, J.; Muñoz-Cámara, M.; Herrera-Fernández, C.; Ávila-Gandía, V.; Heres Fernández Ladreda, M.; Menéndez Martínez, J.; López-Román, F.J. Effectiveness of Enriched Milk with Ashwagandha Extract and Tryptophan for Improving Subjective Sleep Quality in Adults with Sleep Problems: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Clocks Sleep 2024, 6, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Piñero, S.; Muñoz-Carrillo, J.C.; Echepare-Taberna, J.; Muñoz-Cámara, M.; Herrera-Fernández, C.; García-Guillén, A.I.; Ávila-Gandía, V.; Navarro, P.; Caturla, N.; Jones, J.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with an Extract of Aloysia Citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Improves Sleep Quality in Healthy Subjects: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, M.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, J.K.; Kim, J.; Yang, H.; Yoon, M.; Kim, J.; Kang, S.W.; Cho, S. Phlorotannin Supplement Decreases Wake after Sleep Onset in Adults with Self-Reported Sleep Disturbance: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical and Polysomnographic Study. Phytother. Res. Ptr 2018, 32, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, M.Y.; Yang, H.; Han, J.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Kang, S.W.; Yoon, M.; Kwon, S.; Cho, S. Rice Bran Extract Supplement Improves Sleep Efficiency and Sleep Onset in Adults with Sleep Disturbance: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Polysomnographic Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferre, R.; Kuzmiak, C.M. Upgrade Rate of Percutaneously Diagnosed Pure Flat Epithelial Atypia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 1,924 Lesions. J. Osteopath. Med. 2022, 122, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in Meta-Analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepes, S.; Wang, W.; Cortina, J.M. Assessing Publication Bias: A 7-Step User’s Guide with Best-Practice Recommendations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2023, 38, 957–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Tan, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Tian, H.; et al. The Research Advances in Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog (KRAS)-Related Cancer during 2013 to 2022: A Scientometric Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1345737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshima, N.; Sozu, T.; Tajika, A.; Ogawa, Y.; Hayasaka, Y.; Furukawa, T.A. Which Is More Generalizable, Powerful and Interpretable in Meta-Analyses, Mean Difference or Standardized Mean Difference? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Lin, L. Comparisons of the Mean Differences and Standardized Mean Differences for Continuous Outcome Measures on the Same Scale. JBI Evid. Synth. 2024, 22, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Hou, Y.; Lei, Z.; Zhou, S. Multilevel Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Exercise Intervention on Inhibitory Control in Children with ASD. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1632555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, M.; Grenzi, P.; Travascio, A.; Uberti, D.; De Micheli, E.; Quartaroli, F.; Laquatra, G.; Pingani, L.; Ferrari, S.; Galeazzi, G.M. The Effect of Withania Somnifera (Ashwagandha) on Mental Health Symptoms in Individuals with Mental Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BJPsych Open 2025, 11, e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peuhkuri, K.; Sihvola, N.; Korpela, R. Diet Promotes Sleep Duration and Quality. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, T.P.; Ozeki, M.; Juneja, L.R. In Search of a Safe Natural Sleep Aid. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidese, S.; Ogawa, S.; Ota, M.; Ishida, I.; Yasukawa, Z.; Ozeki, M.; Kunugi, H. Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Nagato, Y.; Aoi, N.; Juneja, L.R.; Kim, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Sugimoto, S. Effects of L-Theanine on the Release of α-Brain Waves in Human Volunteers. Nippon. Nōgeikagaku Kaishi 1998, 72, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türközü, D.; Şanlier, N. L-Theanine, Unique Amino Acid of Tea, and Its Metabolism, Health Effects, and Safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jo, K.; Hong, K.-B.; Han, S.H.; Suh, H.J. GABA and L-Theanine Mixture Decreases Sleep Latency and Improves NREM Sleep. Pharm. Biol. 2019, 57, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, R.; Matito, S.; Cubero, J.; Paredes, S.D.; Franco, L.; Rivero, M.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Barriga, C. Tryptophan-Enriched Cereal Intake Improves Nocturnal Sleep, Melatonin, Serotonin, and Total Antioxidant Capacity Levels and Mood in Elderly Humans. Age 2013, 35, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrus, P.; Cervantes, M.; Samad, M.; Sato, T.; Chao, A.; Sato, S.; Koronowski, K.B.; Park, G.; Alam, Y.; Mejhert, N.; et al. Tryptophan Metabolism Is a Physiological Integrator Regulating Circadian Rhythms. Mol. Metab. 2022, 64, 101556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Zadeh, L.F.; Moses, L.; Gwaltney-Brant, S.M. Serotonin: A Review. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 31, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Ding, D.; Bai, D.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D. Melatonin Biosynthesis Pathways in Nature and Its Production in Engineered Microorganisms. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Trakht, I.; Srinivasan, V.; Spence, D.W.; Maestroni, G.J.M.; Zisapel, N.; Cardinali, D.P. Physiological Effects of Melatonin: Role of Melatonin Receptors and Signal Transduction Pathways. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008, 85, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, R.A.; Zafar, N.; Yohannan, S.; Miller, J.-M.M. Melatonin. In Statpearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, S.; Je, N.K.; Suh, H.S. Efficacy of Melatonin for Chronic Insomnia: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 66, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracioli-Oda, E.; Qawasmi, A.; Bloch, M.H. Meta-Analysis: Melatonin for the Treatment of Primary Sleep Disorders. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, I.; Sabir, M.S.; Dussik, C.M.; Whitfield, G.K.; Karrys, A.; Hsieh, J.-C.; Haussier, M.R.; Meyer, M.B.; Pike, J.W.; Jurutka, P.W. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Regulates Expression of the Tryptophan Hydroxylase 2 and Leptin Genes: Implication for Behavioral Influences of Vitamin D. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 4023–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimohammadi-Kamalabadi, M.; Ziaei, S.; Hasani, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Mehrbod, M.; Morvaridi, M.; Persad, E.; Belančić, A.; Malekahmadi, M.; Estêvão, M.D.d.M.A.d.O.; et al. Does Vitamin D Supplementation Impact Serotonin Levels? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, J.; Kang, J.; Kim, T. 0070 Changes In Sleep and Circadian Rhythm In an Animal Model of Vitamin D Deficiency. Sleep 2019, 42, A29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R.P.; Ames, B.N. Vitamin D and the Omega-3 Fatty Acids Control Serotonin Synthesis and Action, Part 2: Relevance for ADHD, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia, and Impulsive Behavior. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 2207–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherasse, Y.; Urade, Y. Dietary Zinc Acts as a Sleep Modulator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhen, S.; Taylor, A.W.; Appleton, S.; Atlantis, E.; Shi, Z. Magnesium Intake and Sleep Disorder Symptoms: Findings from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study of Chinese Adults at Five-Year Follow-Up. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwalfenberg, G.K.; Genuis, S.J. The Importance of Magnesium in Clinical Healthcare. Scientifica 2017, 2017, 4179326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, J.W.; Cho, C.-H. Herbal and Natural Supplements for Improving Sleep: A Literature Review. Psychiatry Investig. 2024, 21, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Lo, Y.-P.; Khaing, I.-K.; Inoue, S.; Tada, A.; Michie, M.; Kubo, T.; Shibata, S.; Tahara, Y. The Association of Sodium or Potassium Intake Timing with Athens Insomnia Scale Scores: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Shi, S.; Ukai-Tadenuma, M.; Fujishima, H.; Ohno, R.-I.; Ueda, H.R. Leak Potassium Channels Regulate Sleep Duration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E9459–E9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.; Kimiagar, M.; Sadeghniiat, K.; Shirazi, M.M.; Hedayati, M.; Rashidkhani, B. The Effect of Magnesium Supplementation on Primary Insomnia in Elderly: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2012, 17, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Li, D.; Huang, T.; Huang, S.; Tan, H.; Xia, Z. Antioxidants and the Risk of Sleep Disorders: Results from NHANES and Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1453064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, B.; Wang, J.; He, R.; Qu, G. Composite Dietary Antioxidant Index and Sleep Health: A New Insight from Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Adults ≥ 19 years, healthy or just suffering from sleep disorders related to diseases |

| Intervention | Consuming dietary supplement(s) or food(s) rich in dietary nutrients that can improve sleep quality |

| Comparison | Not consuming dietary supplement(s) or food(s) rich in dietary nutrients with the function of improving sleep quality, placebo, or standardized diet |

| Outcome | Sleep quality outcomes (SE, SL, TST, WASO, NASO, and PSQI) |

| Study design | RCT |

| Sources of Heterogeneity | Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | 0.082 | 0.629 | −0.286 | 0.450 |

| Country | −0.112 | 0.015 | −0.196 | −0.028 |

| Intervention time | −0.688 | 0.004 | −1.096 | −0.281 |

| Intervention type | −0.191 | 0.002 | −0.294 | −0.087 |

| Sources of Heterogeneity | Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | 0.0452 | 0.811 | −0.346 | 0.437 |

| Country | −0.0823 | 0.080 | −0.176 | 0.011 |

| Intervention time | −0.172 | 0.210 | −0.449 | 0.106 |

| Intervention type | −0.171 | 0.024 | −0.317 | −0.025 |

| Sources of Heterogeneity | Coefficient | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health conditions | 0.410 | 0.074 | −0.045 | 0.866 |

| Country | −0.159 | 0.005 | −0.261 | −0.058 |

| Intervention time | −0.385 | 0.010 | −0.664 | −0.106 |

| Intervention type | −0.078 | 0.247 | −0.215 | 0.060 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mei, M.; Zhou, Q.; Gu, W.; Li, F.; Yang, R.; Lei, H.; Liu, C. Dietary Supplement Interventions and Sleep Quality Improvement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243952

Mei M, Zhou Q, Gu W, Li F, Yang R, Lei H, Liu C. Dietary Supplement Interventions and Sleep Quality Improvement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243952

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Meijuan, Qiya Zhou, Wenting Gu, Feifei Li, Ruili Yang, Hongtao Lei, and Chunhong Liu. 2025. "Dietary Supplement Interventions and Sleep Quality Improvement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243952

APA StyleMei, M., Zhou, Q., Gu, W., Li, F., Yang, R., Lei, H., & Liu, C. (2025). Dietary Supplement Interventions and Sleep Quality Improvement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 17(24), 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243952