Body Image Satisfaction, Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Emotional Management in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from the SI! Program for Secondary Schools Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

2.2. Body Image Satisfaction

2.3. Dietary Assessment

2.4. Emotional Management

2.5. Nutritional Status

2.6. Covariates

2.7. Statistical Methods

3. Results

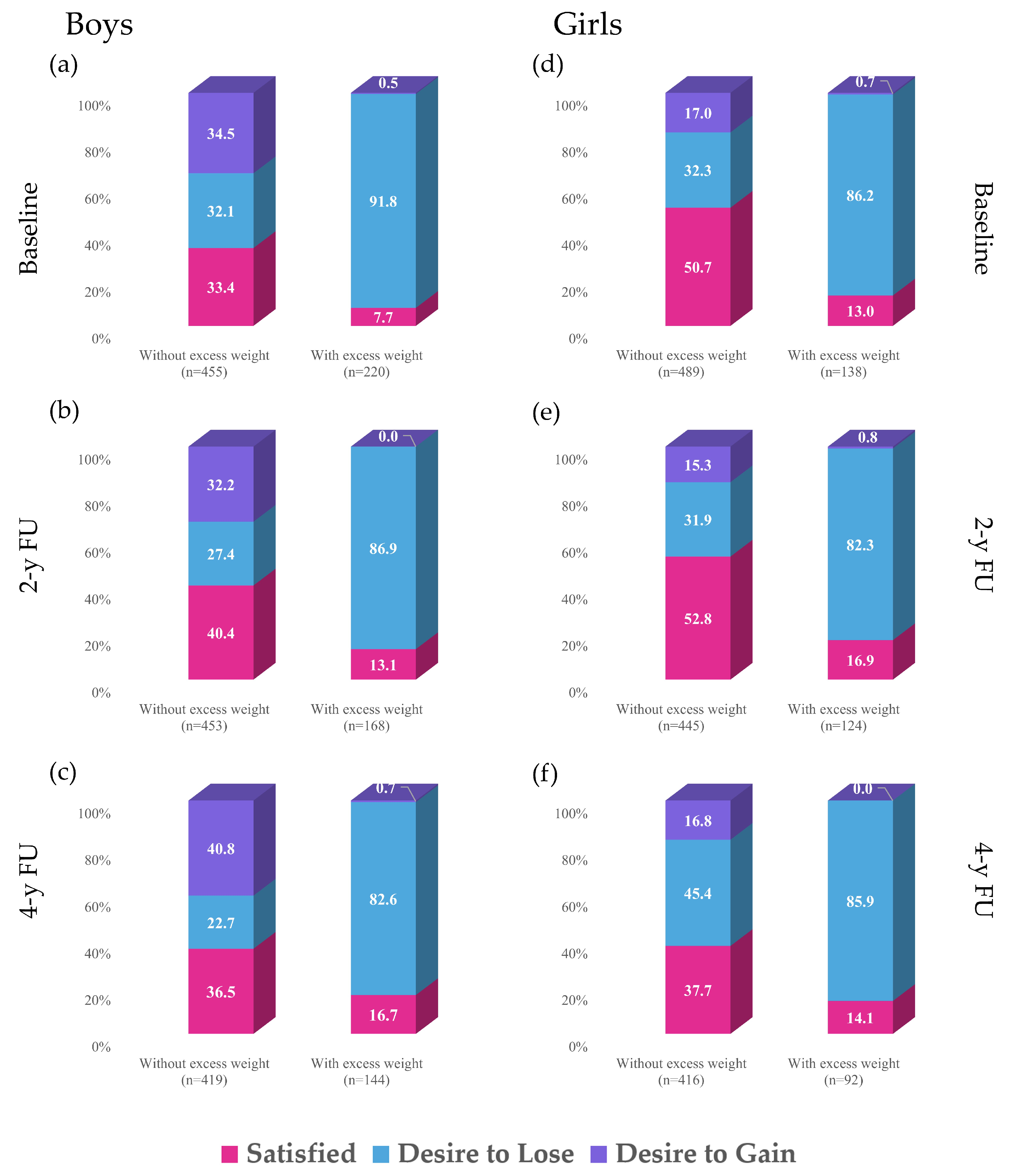

3.1. Body Image Satisfaction and Nutritional Status

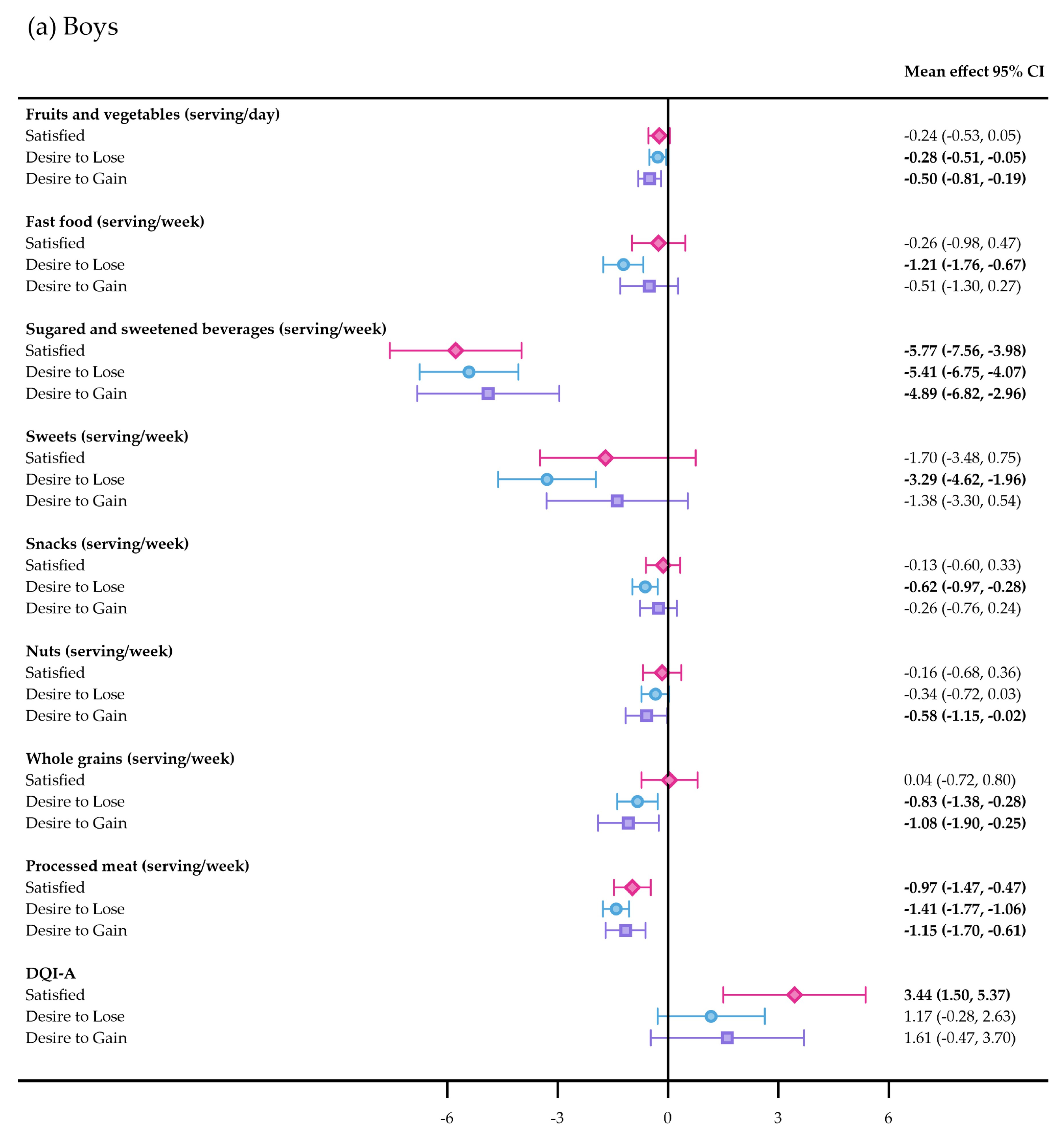

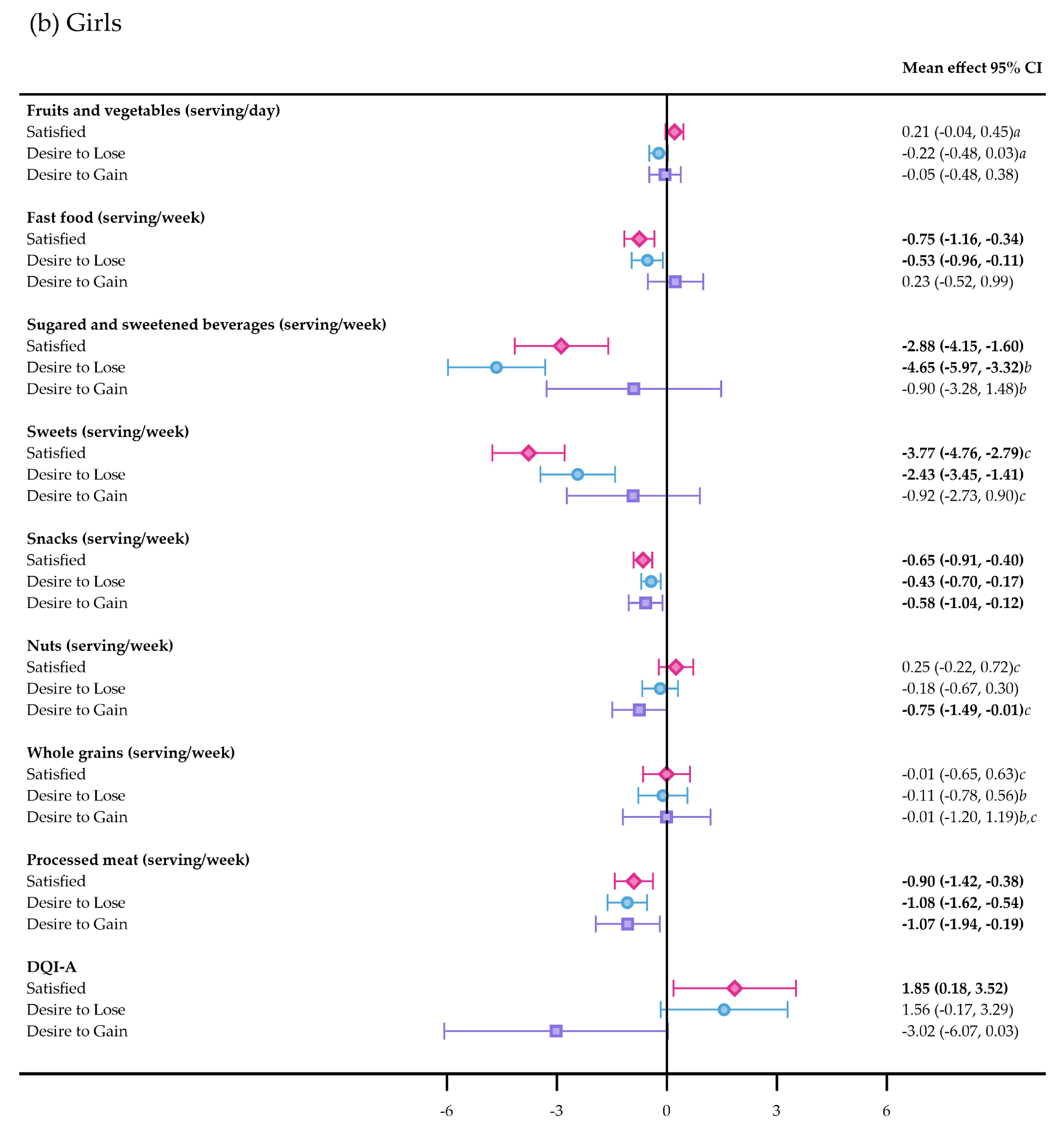

3.2. Body Image Satisfaction and Diet

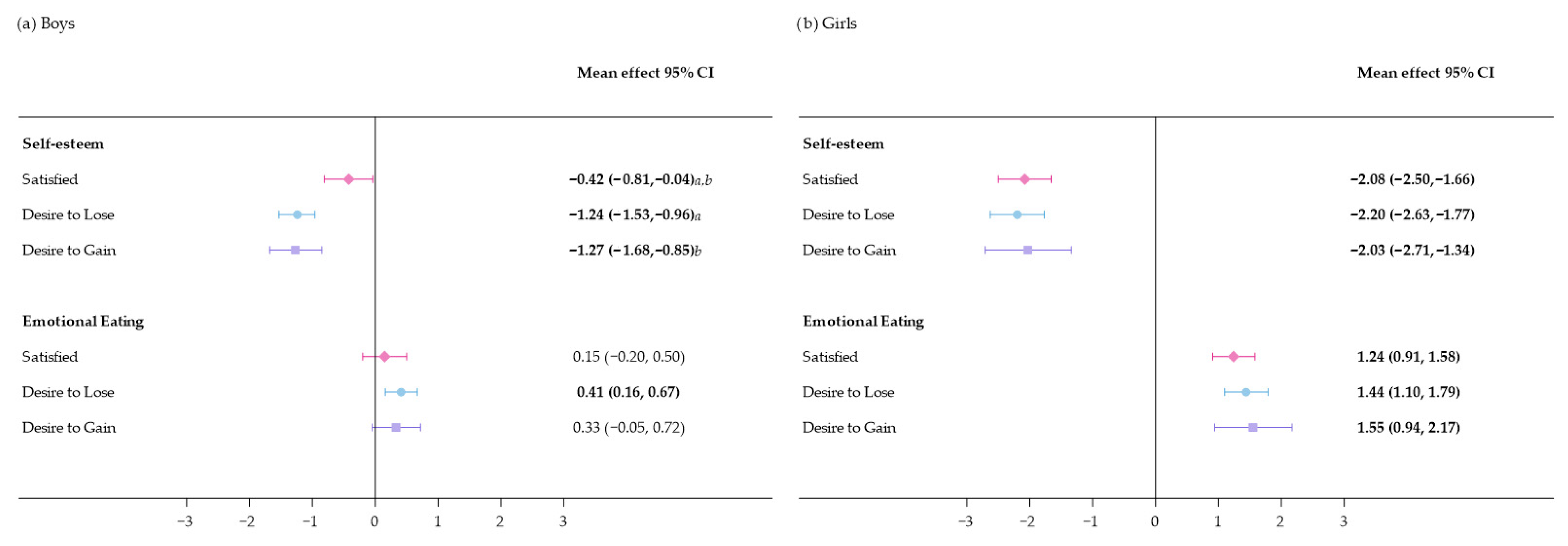

3.3. Body Image Satisfaction and Emotional Management

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BI | Body image |

| BID | Body image dissatisfaction |

| BIS | Body image satisfaction |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CEHQ | Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire |

| DH | Dietary habits |

| DQI-A | Diet Quality Index for Adolescents |

| ISCED | International Standard Classification of Education |

References

- Voelker, D.K.; Reel, J.J.; Greenleaf, C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: Current perspectives. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2015, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Dóriga Alonso, B. La Publicidad y la Salud de las Mujeres: Análisis y Recomendaciones; Instituto de la Mujeres, Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Laveway, K.; Campos, P.; de Carvalho, P.H.B. Body image as a global mental health concern. Camb. Prism. Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibanez-Zamacona, M.E.; Poveda, A.; Rebato, E. Body image in relation to nutritional status in adults from the Basque Country, Spain. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2020, 52, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, J.; Biro, F.M. Different shapes in different cultures: Body dissatisfaction, overweight, and obesity in African-American and caucasian females. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2003, 16, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodega, P.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Moreno, L.A.; Santos-Beneit, G. Body image and dietary habits in adolescents: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 82, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado Otero, M. Mujeres Jóvenes y Trastornos de la Conducta Alimentaria. Impacto de los Roles y Estereotipos de Género; Instituto de las Mujeres, Ministerio de Igualdad: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Khor, G.L.; Zalilah, M.S.; Phan, Y.Y.; Ang, M.; Maznah, B.; Norimah, A.K. Perceptions of body image among Malaysian male and female adolescents. Singap. Med. J. 2009, 50, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, L.S.; Palombo, C.N.T.; Solis-Cordero, K.; Kurihayashi, A.Y.; Steen, M.; Borges, A.L.V.; Fujimori, E. The association between body weight dissatisfaction with unhealthy eating behaviors and lack of physical activity in adolescents: A systematic review. J. Child Health Care 2021, 25, 44–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanlorenci, S.; Gonçalves, L.; Moraes, M.S.; Santiago, L.N.; Pedroso, M.S.; Silva, D.A. Comprehensive scoping review on body image perceptions and influences in children and adolescents. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2716–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Casanova, E.; Molero-Jurado, M.D.M.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C. Self-esteem and risk behaviours in adolescents: A systematic review. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriver, L.H.; Dollar, J.M.; Calkins, S.D.; Keane, S.P.; Shanahan, L.; Wideman, L. Emotional eating in adolescence: Effects of emotion regulation, weight status and negative body image. Nutrients 2021, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.H.; Li, M.D.; Liu, C.J.; Ma, X.Y. Relationship between body image, anxiety, food-specific inhibitory control, and emotional eating in young women with abdominal obesity: A comparative cross-sectional study. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, R.J.; Gasson, S.L. Self esteem/self concept scales for children and adolescents: A review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2005, 10, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenzuela-Luis, N.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Rodríguez-Gómez, J.A.; Sánchez-Gómez, M.B. International comparison of self-concept, self-perception and lifestyle in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: An update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S240–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbers, C.A.; Summers, E. Emotional eating and weight status in adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, P.; Jansen, A. Emotional eating is not what you think it is and emotional eating scales do not measure what you think they measure. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedemann, A.A.; Saules, K.K. The relationship between emotional eating and weight problem perception is not a function of body mass index or depression. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T.; Unger, J.B.; Spruijt-Metz, D. Psychological determinants of emotional eating in adolescence. Eat. Disord. 2009, 17, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Jimenez, R.; Santos-Beneit, G.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Bodega, P.; de Miguel, M.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Carral, V.; Orrit, X.; Haro, D.; et al. Rationale and design of the school-based SI! Program to face obesity and promote health among Spanish adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am. Heart J. 2019, 215, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Beneit, G.; Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Bodega, P.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; de Miguel, M.; Ramirez-Garza, S.L.; Laveriano-Santos, E.P.; Arancibia-Riveros, C.; Carral, V.; et al. School-Based Cardiovascular Health Promotion in Adolescents: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Schiechtl, E.; Rosato, M.S.; Mangweth-Matzek, B.; Cotrufo, P.; Hüfner, K. Body image, self-esteem, emotion regulation, and eating disorders in adults: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatrie 2025, 39, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, N.; Costa, M.A.; Gosmann, N.P.; Dalle Molle, R.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Silva, A.C.; Rodrigues, Y.; Silveira, P.P.; Manfro, G.G. Emotional eating in women with generalized anxiety disorder. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2023, 45, e20210399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiden-Rootes, K.; Linsenmeyer, W.; Levine, S.; Oliveras, M.; Joseph, M. A scoping review of the research literature on eating and body image for transgender and nonbinary adults. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Ocke, M.C.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Hornell, A.; Larsson, C.; Sonestedt, E.; Wirfalt, E.; Akesson, A.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology-Nutritional Epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Sorensen, T.; Schulsinger, F. Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of obesity and thinness. Res. Publ. Assoc. Res. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 60, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes-Martínez, G.; Vallejo-de la Cruz, N.L.; Pérez-Salgado, D.; Ortiz-Hernández, L. Utilidad de siluetas corporales en la evaluación del estado nutricional en escolares y adolescentes de la Ciudad de México. Bol. Méd. Hosp. Infant. México 2009, 66, 511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ayed, H.; Yaich, S.; Ben Jemaa, M.; Ben Hmida, M.; Trigui, M.; Jedidi, J.; Sboui, I.; Karray, R.; Feki, H.; Mejdoub, Y.; et al. What are the correlates of body image distortion and dissatisfaction among school-adolescents? Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 33, 20180279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel-Serrat, S.; Mouratidou, T.; Pala, V.; Huybrechts, I.; Bornhorst, C.; Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Hadjigeorgiou, C.; Eiben, G.; Hebestreit, A.; Lissner, L.; et al. Relative validity of the Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire-food frequency section among young European children: The IDEFICS Study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfer, A.; Hebestreit, A.; Ahrens, W.; Krogh, V.; Sieri, S.; Lissner, L.; Eiben, G.; Siani, A.; Huybrechts, I.; Loit, H.M.; et al. Reproducibility of food consumption frequencies derived from the Children’s Eating Habits Questionnaire used in the IDEFICS study. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, S61–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Alvira, J.M.; Bornhorst, C.; Bammann, K.; Gwozdz, W.; Krogh, V.; Hebestreit, A.; Barba, G.; Reisch, L.; Eiben, G.; Iglesia, I.; et al. Prospective associations between socio-economic status and dietary patterns in European children: The Identification and Prevention of Dietary- and Lifestyle-induced Health Effects in Children and Infants (IDEFICS) Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesia, I.; Intemann, T.; De Miguel-Etayo, P.; Pala, V.; Hebestreit, A.; Wolters, M.; Russo, P.; Veidebaum, T.; Papoutsou, S.; Nagy, P.; et al. Dairy Consumption at Snack Meal Occasions and the Overall Quality of Diet during Childhood. Prospective and Cross-Sectional Analyses from the IDEFICS/I.Family Cohort. Nutrients 2020, 12, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyncke, K.; Cruz Fernandez, E.; Fajo-Pascual, M.; Cuenca-Garcia, M.; De Keyzer, W.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Moreno, L.A.; Beghin, L.; Breidenassel, C.; Kersting, M.; et al. Validation of the Diet Quality Index for adolescents by comparison with biomarkers, nutrient and food intakes: The HELENA study. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, J.A.; Cámara, M.; Giner, R.; González, E.; López, E.; Mañes, J.; Portillo, M.P.; Rafecas, M.; Gutiérrez, E.; García, M.; et al. Informe del Comité Científico de la Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN) de revisión y actualización de las Recomendaciones Dietéticas para la población española. Rev. Com. Científico AESAN 2020, 32, 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Recomendaciones de Consumo de Pescado por Presencia de Mercurio: Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN). 2023. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/seguridad_alimentaria/ampliacion/mercurio.htm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Rajmil, L.; Serra-Sutton, V.; Alonso, J.; Herdman, M.; Riley, A.; Starfield, B. Validity of the Spanish version of the Child Health and Illness Profile-Adolescent Edition (CHIP-AE). Med. Care 2003, 41, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui-Lobera, I.; Garcia-Cruz, P.; Carbonero-Carreno, R.; Magallares, A.; Ruiz-Prieto, I. Psychometric properties of Spanish version of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 (TFEQ-SP) and its relationship with some eating- and body image-related variables. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5619–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.L.; Brazendale, K.; Beets, M.W.; Mealing, B.A. Classification of physical activity intensities using a wrist-worn accelerometer in 8-12-year-old children. Pediatr. Obes. 2016, 11, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, N.; Sanchez, C.E.; Vera, J.A.; Perez, W.; Thalabard, J.C.; Rieu, M. A physical activity questionnaire: Reproducibility and validity. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 505–518. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, J.M.; Whitehouse, R.H. Clinical longitudinal standards for height, weight, height velocity, weight velocity, and stages of puberty. Arch. Dis. Child. 1976, 51, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 2011; UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS): Montreal, QC, Cananda, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, N.A.; Kersting, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Compared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Facts 2016, 9, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Thompson, J.K.; Cash, T.F. Body image and obesity in adulthood. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 28, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Latner, J.D. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, E.L.; Halliwell, E.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Harcourt, D. Happy Being Me in the UK: A controlled evaluation of a school-based body image intervention with pre-adolescent children. Body Image 2013, 10, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balluck, G.; Toorabally, B.Z.; Hosenally, M. Association between body image dissatisfaction and body mass index, eating habits and weight control practices among mauritian adolescents. Mal. J. Nutr. 2016, 22, 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.W.; Liou, T.H.; Liou, Y.M.; Chen, H.J.; Chien, L.Y. Measurements and profiles of body weight misperceptions among Taiwanese teenagers: A national survey. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 25, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, M.L.; Tee, M.S.Y.; Garnett, S.P.; Baur, L.A.; Aldwell, K.; Thomas, S.; Lister, N.B.; Paxton, S.J.; Jebeile, H. Pediatric obesity treatment, self-esteem, and body image: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, J.E.; Schaefer, L.M.; Burke, N.L.; Mayhew, L.L.; Brannick, M.T.; Thompson, J.K. Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2010, 7, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y. Athlete Body Image and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review of Their Association and Influencing Factors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzas, C.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Tur, J.A. Relationship between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, H.; Lee, H.; Ro, Y.; Gray, H.L.; Song, K. Body image, weight management behavior, nutritional knowledge and dietary habits in high school boys in Korea and China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, Y.; Hyun, W. Comparative study on body shape satisfaction and body weight control between Korean and Chinese female high school students. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2012, 6, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibiloni Mdel, M.; Martinez, E.; Llull, R.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A. Western and Mediterranean dietary patterns among Balearic Islands’ adolescents: Socio-economic and lifestyle determinants. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaban, L.H.; Vaccaro, J.A.; Sukhram, S.D.; Huffman, F.G. Perceived Body Image, Eating Behavior, and Sedentary Activities and Body Mass Index Categories in Kuwaiti Female Adolescents. Int. J. Pediatr. 2016, 2016, 1092819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, T.M.; Jorge, M.L.; David, S.O.; Mikel, V.S.; Antonio, S.P. Mediating effect of fitness and fatness on the association between lifestyle and body dissatisfaction in Spanish youth. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 232, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro-Silva, R.C.; Fiaccone, R.L.; Conceicao-Machado, M.; Ruiz, A.S.; Barreto, M.L.; Santana, M.L.P. Body image dissatisfaction and dietary patterns according to nutritional status in adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2018, 94, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, I. Food habits and body image of students in Lausanne. Rev. Med. Suisse 2008, 4, 1432–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Bibiloni Mdel, M.; Pich, J.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A. Body image and eating patterns among adolescents. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.U.D.; Alves, M.A.; Vasconcelos, F.A.G.; Goncalves, V.S.S.; Barufaldi, L.A.; Carvalho, K.M.B. Association between body weight misperception and dietary patterns in Brazilian adolescents: Cross-sectional study using ERICA data. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebar, W.R.; Gil, F.C.S.; Scarabottolo, C.C.; Codogno, J.S.; Fernandes, R.A.; Chistofaro, D.G.D. Body size dissatisfaction associated with dietary pattern, overweight, and physical activity in adolescents—A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatman, T.; Watson, C.M. Gender differences in adolescent self-esteem: An exploration of domains. J. Genet. Psychol. 2001, 162, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Story, M.; Perry, C.L. Self-esteem and obesity in children and adolescents: A literature review. Obes. Res. 1995, 3, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, J.; Rice, C. Beyond “healthy eating” and “healthy weights”: Harassment and the health curriculum in middle schools. Body Image 2005, 2, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Mayhew, S.; McVey, G.; Bardick, A.; Ireland, A. Mental health, wellness, and childhood overweight/obesity. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 281801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annesi, J.J. Relation of changes in body satisfaction with propensities for emotional eating within a community-delivered obesity treatment for women: Theory-based mediators. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Ersig, A.L.; McCarthy, A.M. The Influence of Peers on Diet and Exercise Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 36, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbard, J.R.; Lee, C.M.; Neighbors, C.; Larimer, M.E. Body Image Concerns and Contingent Self-Esteem in Male and Female College Students. Sex Roles 2009, 60, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brichacek, A.L.; Neill, J.T.; Murray, K.; Rieger, E.; Watsford, C. The Effectiveness of Body Image Flexibility Interventions in Youth: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2025, 10, 455–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, M.; Rosendahl, J.; Rodeck, J.; Muehleck, J.; Berger, U. School-Based Interventions Improve Body Image and Media Literacy in Youth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Prev. 2022, 43, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.A.; Lalonde, C.E.; Bain, J.L. Body image perceptions: Do gender differences exist. Psi Chi J. Undergrad. Res. 2010, 15, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. What is the best response scale for survey and questionnaire design; review of different lengths of rating scale/attitude scale/Likert scale. Int. J. Res. Manag. 2019, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

| Overall | Boys | Girls | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 1315 | 681 (51.8%) | 634 (48.2%) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 12.5 (0.4) | 12.6 (0.5) | 12.5 (0.4) | 0.026 |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| Madrid | 420 (31.9%) | 223 (32.8%) | 197 (31.1%) | 0.515 |

| Barcelona | 895 (68.1%) | 458 (67.3%) | 437 (68.9%) | |

| Migrant background, n (%) | ||||

| Spanish | 868 (66.0%) | 451 (66.2%) | 417 (65.8%) | 0.696 |

| Migrant background | 428 (32.6%) | 222 (32.6%) | 206 (32.5%) | |

| Unknown | 19 (1.4%) | 8 (1.2%) | 11 (1.7%) | |

| Parental education level | ||||

| Low | 245 (18.6%) | 116 (17.0%) | 129 (20.4%) | 0.342 |

| Intermediate | 533 (40.5%) | 275 (40.4%) | 258 (40.7%) | |

| High | 520 (39.5%) | 282 (41.4%) | 238 (37.5%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (1.3%) | 8 (1.2%) | 9 (1.4%) | |

| Nutritional status, n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 38 (2.9%) | 22 (3.2%) | 16 (2.6%) | <0.001 |

| Normal weight | 909 (69.6%) | 436 (64.3%) | 473 (75.3%) | |

| Overweight | 230 (17.6%) | 144 (21.2%) | 86 (13.7%) | |

| Obesity | 129 (9.9%) | 76 (11.2%) | 53 (8.4%) | |

| Body image satisfaction, n (%) | ||||

| Satisfied | 437 (33.4%) | 169 (25.0%) | 268 (42.3%) | <0.001 |

| Desire to lose weight | 629 (48.0%) | 348 (51.4%) | 281 (44.4%) | |

| Desire to gain weight | 244 (18.6%) | 160 (23.6%) | 84 (13.3%) | |

| DQI-A, mean (SD) | 57.7 (12.9) | 56.7 (13.0) | 58.8 (12.7) | 0.004 |

| Diet quality | 42.2 (24.6) | 38.9 (25.1) | 45.7 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| Dietary diversity | 78.9 (16.7) | 79.7 (16.9) | 78.0 (16.4) | 0.062 |

| Dietary equilibrium | 52.0 (11.8) | 51.5 (11.7) | 52.6 (11.9) | 0.098 |

| Self-esteem, mean (SD) | 15.6 (1.8) | 15.6 (1.8) | 15.5 (1.8) | 0.221 |

| Emotional eating, mean (SD) | 4.6 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.0) | 0.852 |

| REPEATED MEASURES AT BASELINE, 2- AND 4-YEAR FOLLOW-UP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |||||

| Satisfied | Desire to Lose | Desire to Gain | Satisfied | Desire to Lose | Desire to Gain | |

| Dietary Habits | ||||||

| Fruits and vegetables (serving/day) | 2.1 (2.0; 2.3) | 2.1 (2.0; 2.3) | 2.1 (1.9; 2.3) | 2.3 (2.1; 2.5) | 2.3 (2.1; 2.5) | 2.1 (1.8; 2.4) |

| Fast food (serving/week) | 4.5 (4.0; 5.1) a | 4.1 (3.6; 4.7) b | 5.6 (5.0; 6.2) a,b | 3.8 (3.4; 4.2) | 3.6 (3.2; 4.0) | 4.1 (3.5; 4.7) |

| Sugared and sweetened beverages (serving/week) | 14.4 (12.9; 16.0) | 12.6 (11.1; 14.0) | 14.7 (13.0; 16.4) | 11.3 (9.3; 13.3) | 10.8 (8.8; 12.9) | 11.4 (9.1; 13.8) |

| Sweets (serving/week) | 10.1 (9.0; 11.3) | 8.8 (7.7; 9.9) b | 11.8 (10.5; 13.1) b | 10.4 (8.6; 12.1) | 9.7 (8.0; 11.4) | 10.9 (8.7; 13.1) |

| Snacks (serving/week) | 2.0 (1.6; 2.5) | 1.9 (1.4; 2.3) b | 2.4 (2.0; 2.9) b | 2.0 (1.5; 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4; 2.5) | 2.5 (1.9; 3.1) |

| Nuts (serving/week) | 2.1 (1.7; 2.5) | 2.0 (1.6; 2.3) | 2.5 (2.1; 2.9) | 2.2 (1.5; 2.8) | 2.2 (1.5; 2.8) | 2.1 (1.4; 2.9) |

| Whole grains (serving/week) | 3.4 (2.4; 4.4) | 3.2 (2.2; 4.2) | 3.8 (2.8; 4.9) | 3.3 (2.6; 3.9) | 3.7 (3.1; 4.4) | 2.9 (2.0; 3.8) |

| Processed meat (serving/week) | 4.0 (3.7; 4.4) a | 3.9 (3.6; 4.2) b | 4.8 (4.3; 5.2) a,b | 3.9 (3.5; 4.2) | 4.2 (3.9; 4.6) | 4.6 (4.0; 5.2) |

| DQI-A | 57.2 (55.7; 58.7) | 58.3 (56.8; 59.7) | 56.8 (55.1; 58.4) | 59.4 (58.0; 60.9) | 59.8 (58.4; 61.3) | 58.4 (56.4; 60.4) |

| Emotional Management | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 15.5 (15.3; 15.7) a,c | 14.9 (14.7; 15.2) c | 15.0 (14.8; 15.2) a | 14.9 (14.7; 15.2) a,c | 14.1 (13.9; 14.3) c | 14.4 (14.0; 14.7) a |

| Emotional Eating | 4.5 (4.2; 4.8) | 4.7 (4.3; 5.0) | 4.7 (4.4; 5.0) | 5.0 (4.8; 5.2) a,c | 5.4 (5.2; 5.6) c | 5.7 (5.4; 6.0) a |

| REPEATED MEASURES AT BASELINE, 2- AND 4-YEAR FOLLOW-UP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Satisfied | Desire to Lose | Desire to Gain | Satisfied | Desire to Lose | Desire to Gain | |

| Dietary Habits | ||||||

| Fruits and vegetables | [Ref] | 1.10 (0.76; 1.61) | 0.86 (0.58; 1.29) | [Ref] | 0.89 (0.63; 1.27) | 0.75 (0.45; 1.23) |

| Fast food | - | 0.85 (0.58; 1.24) | 1.77 (1.21; 2.59) | - | 0.79 (0.56; 1.11) | 1.39 (0.87; 2.20) |

| Sugared and sweetened beverages | - | 0.54 (0.37; 0.79) | 0.98 (0.67; 1.42) | - | 0.75 (0.53; 1.04) | 1.09 (0.69; 1.72) |

| Sweets | - | 0.64 (0.44; 0.92) | 1.86 (1.29; 2.68) | - | 0.73 (0.52; 1.00) | 1.21 (0.79; 1.88) |

| Snacks | - | 0.97 (0.59; 1.62) | 1.85 (1.13; 3.03) | - | 0.75 (0.48; 1.18) | 1.42 (0.81; 2.49) |

| Nuts | - | 0.92 (0.60; 1.39) | 1.15 (0.75; 1.77) | - | 0.82 (0.57; 1.18) | 0.91 (0.55; 1.51) |

| Whole grains | - | 1.03 (0.72; 1.48) | 0.99 (0.67; 1.45) | - | 1.20 (0.87; 1.65) | 0.77 (0.48; 1.24) |

| Processed meat | - | 0.85 (0.59; 1.24) | 1.37 (0.94; 2.00) | - | 1.23 (0.87; 1.73) | 1.19 (0.74; 1.92) |

| DQI-A | - | 1.25 (0.83; 1.89) | 0.85 (0.55; 1.31) | - | 1.16 (0.79; 1.71) | 0.92 (0.54; 1.58) |

| Emotional Management | ||||||

| Self-esteem | [Ref] | 0.57 (0.40; 0.81) | 0.66 (0.46; 0.95) | [Ref] | 0.44 (0.31; 0.63) | 0.45 (0.26; 0.77) |

| Emotional Eating | - | 1.27 (0.85; 1.88) | 1.45 (0.96; 2.19) | - | 1.20 (0.85; 1.70) | 2.06 (1.28; 3.32) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bodega, P.; Fernández-Alvira, J.M.; de Cos-Gandoy, A.; Moreno, L.A.; de Miguel, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Martínez-Gómez, J.; Laveriano-Santos, E.P.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Estruch, R.; et al. Body Image Satisfaction, Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Emotional Management in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from the SI! Program for Secondary Schools Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243882

Bodega P, Fernández-Alvira JM, de Cos-Gandoy A, Moreno LA, de Miguel M, Rodríguez C, Martínez-Gómez J, Laveriano-Santos EP, Castro-Barquero S, Estruch R, et al. Body Image Satisfaction, Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Emotional Management in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from the SI! Program for Secondary Schools Trial. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243882

Chicago/Turabian StyleBodega, Patricia, Juan M. Fernández-Alvira, Amaya de Cos-Gandoy, Luis A. Moreno, Mercedes de Miguel, Carla Rodríguez, Jesús Martínez-Gómez, Emily P. Laveriano-Santos, Sara Castro-Barquero, Ramón Estruch, and et al. 2025. "Body Image Satisfaction, Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Emotional Management in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from the SI! Program for Secondary Schools Trial" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243882

APA StyleBodega, P., Fernández-Alvira, J. M., de Cos-Gandoy, A., Moreno, L. A., de Miguel, M., Rodríguez, C., Martínez-Gómez, J., Laveriano-Santos, E. P., Castro-Barquero, S., Estruch, R., Lamuela-Raventós, R. M., Fernández-Jiménez, R., & Santos-Beneit, G. (2025). Body Image Satisfaction, Food Consumption, Diet Quality, and Emotional Management in Adolescence: A Longitudinal Analysis from the SI! Program for Secondary Schools Trial. Nutrients, 17(24), 3882. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243882