Mice Condition Cephalic Insulin Responses to the Flavor of Different Laboratory Chows

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Animals, Housing Conditions and Protocol Approvals

2.2. Types of Chow

2.3. Measurement of Blood Glucose and Plasma Insulin

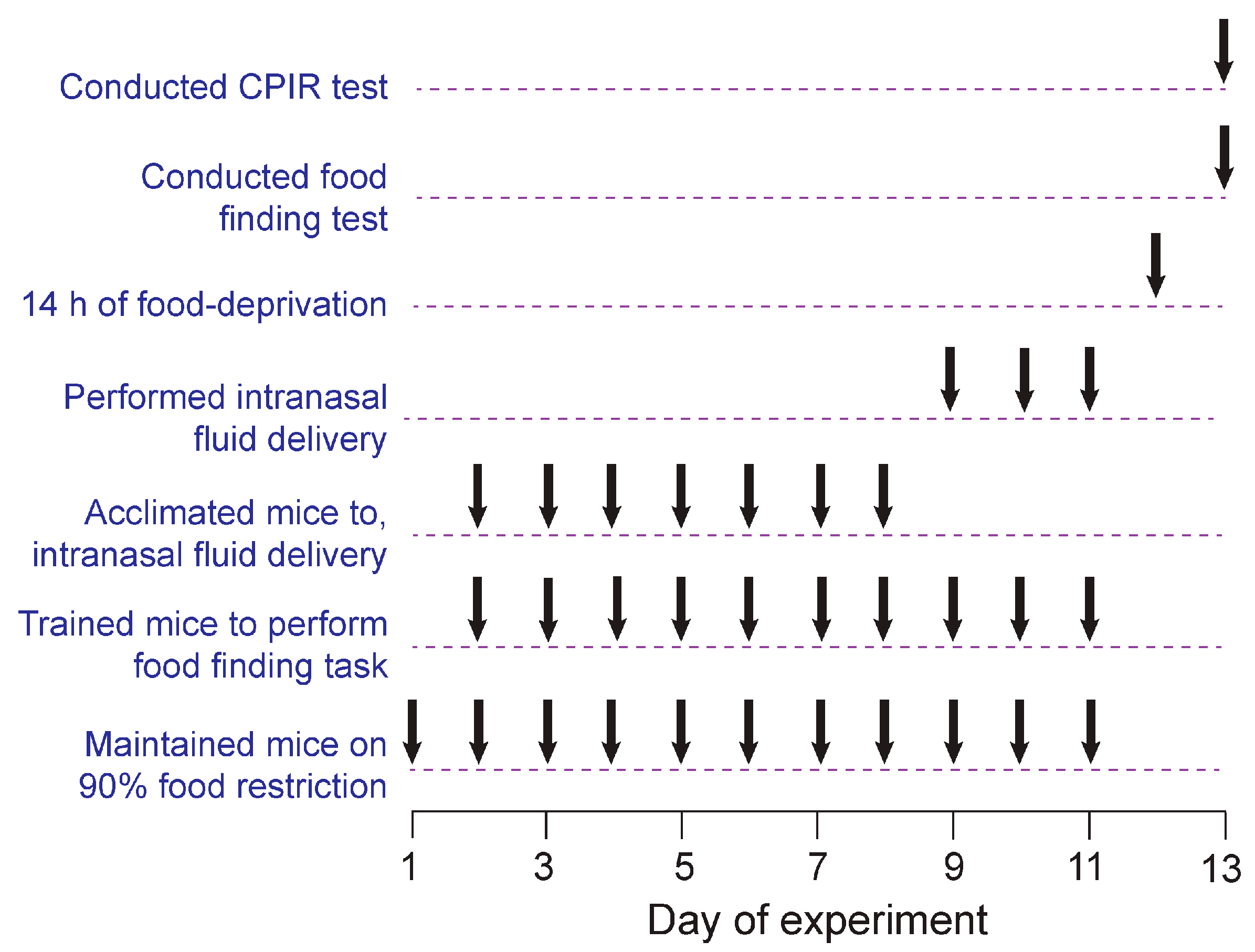

2.4. Attempt to Replicate Prior CPIR Results with Familiar Lab Chow (Experiment 1)

2.4.1. Between-Subjects Design

2.4.2. Matched Pairs Design

2.5. CPIR Test (Experiments 2–5)

2.6. How Much Chewing Is Required to Elicit a CPIR? (Experiment 2)

2.7. Is Conditioning Required for Standard or Purified Chow to Elicit a CPIR? (Experiment 3)

2.8. Ingestion Rates on Standard Versus Purified Chow (Experiment 4)

2.9. Is Olfaction a Necessary Component of the Conditioned CPIR to Both Types of Chow? (Experiment 5)

2.9.1. Experimental Design

2.9.2. Method for Impairing Olfaction

2.9.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

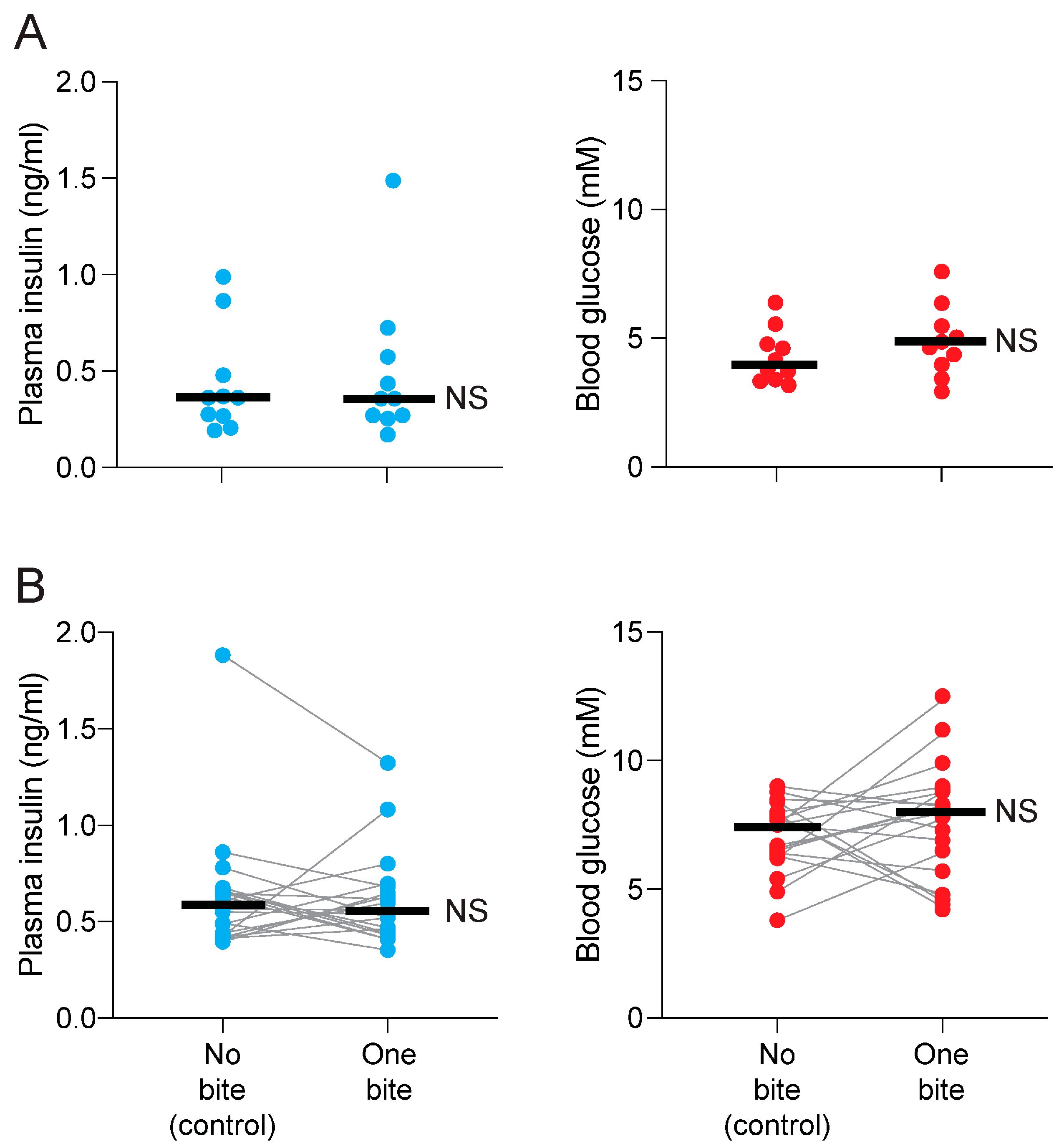

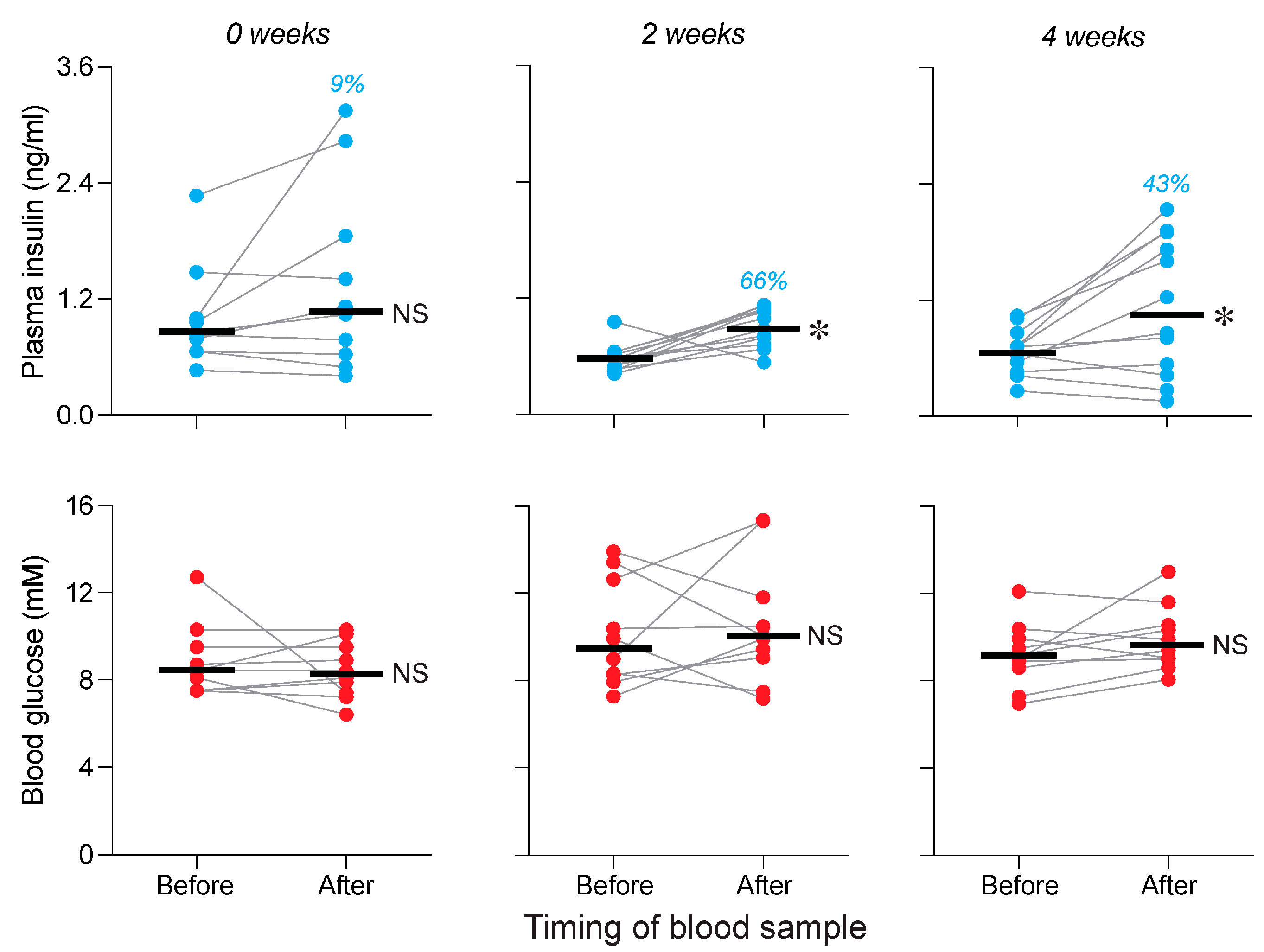

3.1. Attempt to Replicate Prior CPIR Results with Familiar Lab Chow (Experiment 1)

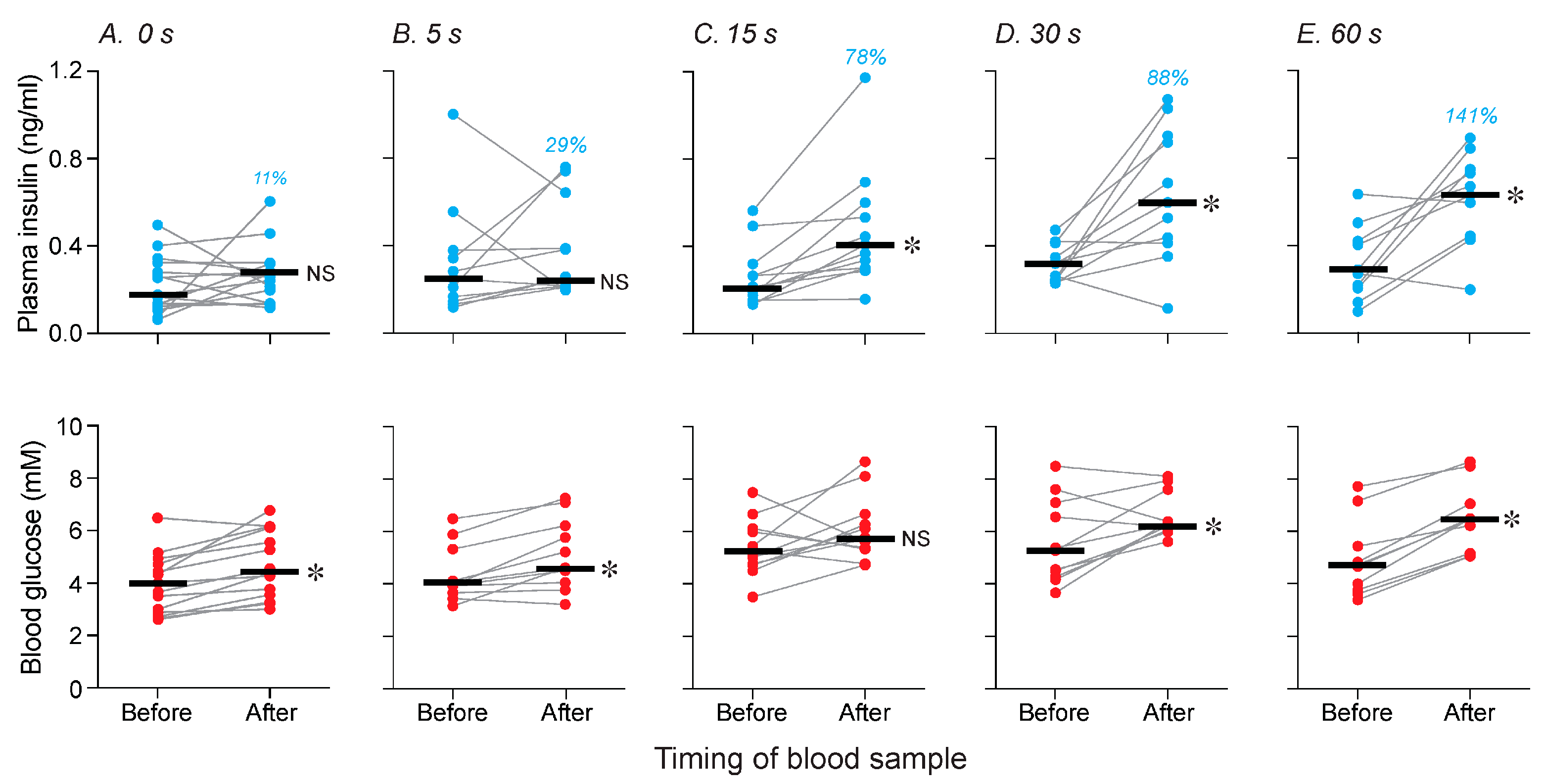

3.2. How Much Chewing Is Required for Standard Chow to Elicit a CPIR? (Experiment 2)

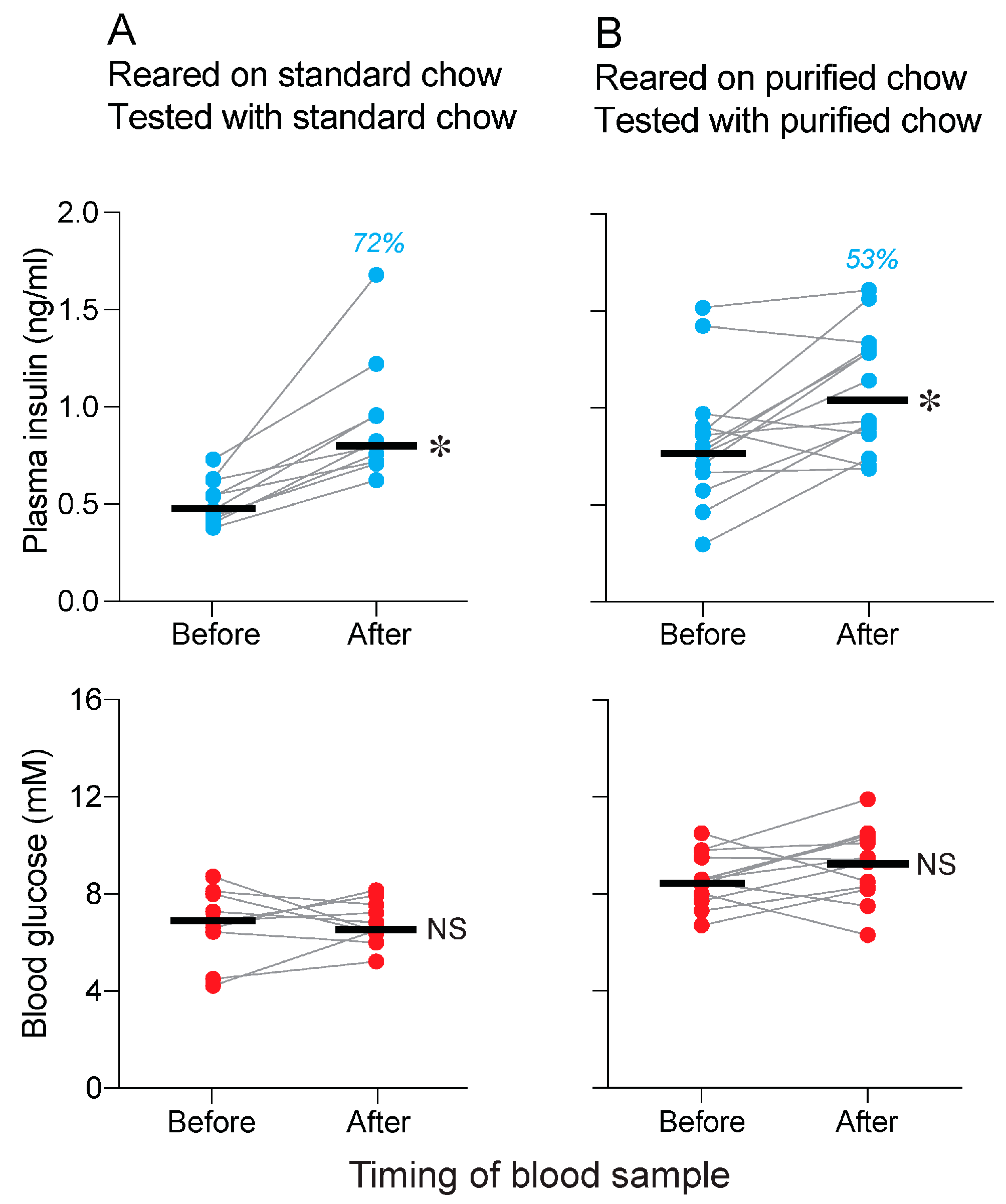

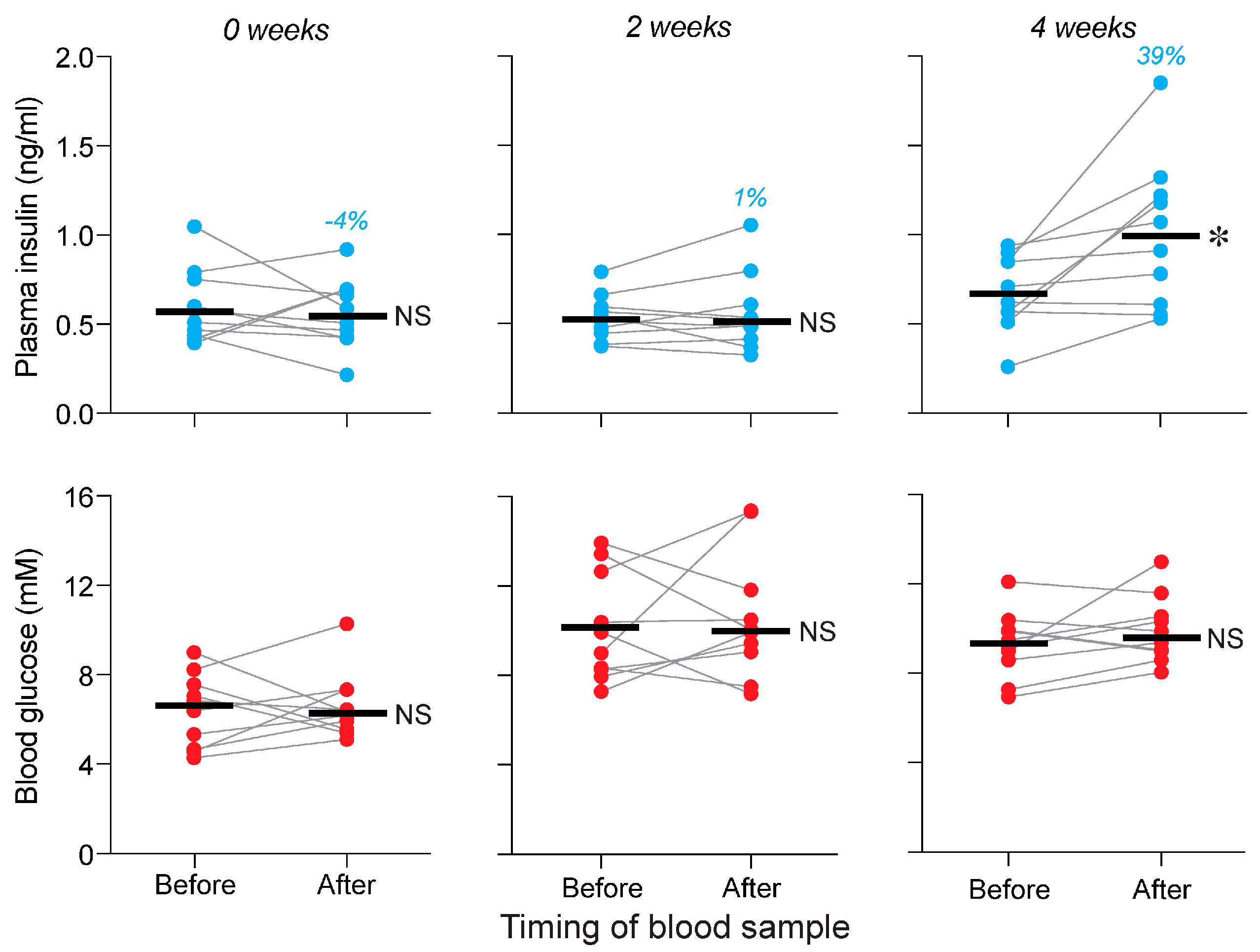

3.3. Is Conditioning Required for Standard and Purified Chows to Elicit a CPIR (Experiment 3)

3.4. Ingestion Rates on Standard Versus Purified Chow (Experiment 4)

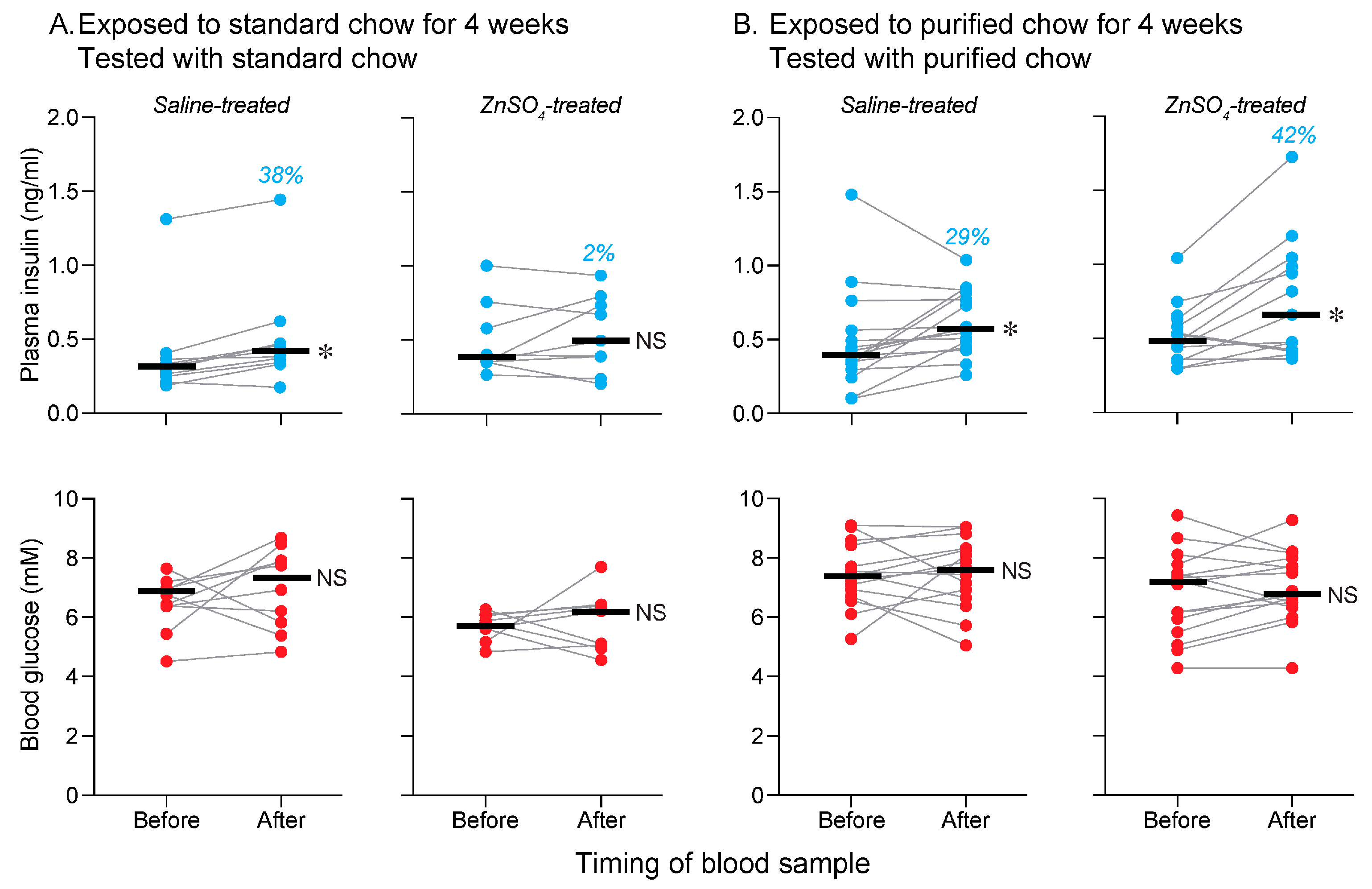

3.5. Is Olfactory Input a Necessary Component of the Conditioned CPIR Stimulus? (Experiment 5)

4. Discussion

4.1. Amount of Chewing Required to Trigger a CPIR in Mice

4.2. The Chow-Induced Cephalic Insulin Responses Required Conditioning

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of Study Design

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B6 mice | C57BL/6 mice |

| CPR | cephalic-phase response |

| CPIR | cephalic-phase insulin response |

References

- Strubbe, J.H.; Steffens, A.B. Rapid insulin release after ingestion of a meal in the unanesthetized rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1975, 229, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellisle, F.; Louis-Sylvestre, J.; Demozay, F.; Blazy, D.; Le Magnen, J. Reflex insulin response associated to food intake in human subjects. Physiol. Behav. 1983, 31, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teff, K.L. How neural mediation of anticipatory and compensatory insulin release helps us tolerate food. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 103, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.J.; Rachid, L.; Illigens, B.; Böni-Schnetzler, M.; Marc, Y.; Donath, M.Y. Evidence for cephalic phase insulin release in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 2020, 155, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullicin, A.J.; Glendinning, J.I.; Lim, J. Cephalic phase insulin release: A review of its mechanistic basis and variability in humans. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 239, 113514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, W.; Watts, A.G.; Spector, A.C. The elusive cephalic phase insulin response: Triggers, mechanisms, and functions. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 103, 1423–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimble, E.R.; Berthoud, H.R.; Siegel, E.G.; Jeanrenaud, B.; Renold, A.E. Importance of cholinergic innervation of the pancreas for glucose tolerance in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1981, 241, E337–E341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.-C.; Hermans, M.P.; Henquin, J.-C. Glucose-, calcium- and concentration-dependence of acetylcholine stimulation of insulin release and ionic fluxes in mouse islets. Biochem. J. 1988, 254, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalich, W.S.; Zawalich, K.C.; Rasmussen, H. Cholinergic agonists prime the b-cell to glucose stimulation. Endocrinology 1989, 125, 2400–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzi, L.; DeFronzo, R.A. Effect of loss of first-phase insulin secretion on hepatic glucose production and tissue glucose disposal in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endo. Metabol. 1989, 257, E241–E246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, K.; Grill, H.J.; Norgren, R. Relation of consummatory responses and preabsorptive insulin release to palatability and learned taste aversions. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1981, 95, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, Y.; Sako, N.; Yamaguchi, R.; Funakoshi, M. Disappearance of preabsorptive insulin responses to sweet tasting stimuli in the rat conditioned taste aversion. Jpn. J. Oral. Biol. 1989, 31, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, S.C.; Vasselli, J.R.; Kaestner, E.; Szakmary, G.A.; Milburn, P.; Vitiello, M.V. Conditioned insulin secretion and meal feeding in rats. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1977, 91, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubbe, J.H. Parasympathetic involvement in rapid meal-associated conditioned insulin secretion in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1992, 263, R615–R618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaner, M.; Denom, J.; Jiang, W.; Magnan, C.; Trapp, S.; Gurden, H. The local GLP-1 system in the olfactory bulb is required for odor-evoked cephalic phase of insulin release in mice. Molec. Metabol. 2023, 73, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, J.I.; Archambeau, A.; Brouwer, L.R.; Dennis, A.; Georgiou, K.; Ivanov, J.; Vayntrub, R.; Sclafani, A. Mice condition cephalic-phase insulin release to flavors associated with postoral actions of concentrated glucose. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthoud, H.R.; Jeanrenaud, B. Sham feeding-induced cephalic phase insulin release in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1982, 242, E280–E285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, S.J.; Trimigliozzi, K.; Dror, E.; Meier, D.T.; Molina-Tijeras, J.A.; Rachid, L.; Le Foll, C.; Magnan, C.; Schulze, F.; Stawiski, M.; et al. The cephalic phase of insulin release is modulated by IL-1b. Cell Metabol. 2022, 34, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togashi, Y.; Shirakawa, J.; Okuyama, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Kyohara, M.; Miyazawa, A.; Suzuki, T.; Hamada, M.; Terauchi, Y. Evaluation of the appropriateness of using glucometers for measuring the blood glucose levels in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rorsman, P.; Ashcroft, F.M. Pancreatic beta-cell electrical activity and insulin secretion: Of mice and men. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 117–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delay, E.R.; Kondoh, T. Dried bonito dashi: Taste qualities evaluated using conditioned taste aversion methods in wild-type and T1R1 knockout mice. Chem. Senses 2015, 40, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, L.R.; Fine, J.M.; Svitak, A.L.; Faltesek, K.A. Intranasal administration of CNS therapeutics to awake mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 74, e4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendinning, J.I.; Maleh, J.; Ortiz, G.; Touzani, K.; Sclafani, A. Olfaction contributes to the learned avidity for glucose relative to fructose in mice. Am. J. Physiol. 2020, 318, R901–R916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubbe, J.H. Central nervous system and insulin secretion. Neth. J. Med. 1989, 34, 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, J.I.; Lubitz, G.S.; Shelling, S. Taste of glucose elicits cephalic-phase insulin release in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 192, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendinning, J.I.; Drimmer, Z.; Isbar, R. Individual differences in cephalic-phase insulin response are stable over time and predict glucose tolerance in mice. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 276, 114476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennard, M.R.; Daniels-Gatward, L.F.; Roberts, A.G.; White, E.R.P.; Nandi, M.; King, A.J.F. The use of mice in diabetes research: The impact of experimental protocols. Diabet. Med. 2021, 38, e14705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennard, M.R.; Nandi, M.; Chapple, S.; King, A.J. The glucose tolerance test in mice: Sex, drugs and protocol. Diab. Obes. Metabol. 2022, 24, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, B.W.; Delse, F.C.; Bryson, M.R. Human salivary conditioning: Effect of unconditioned-stimulus intensity. J. Exp. Psychol. 1967, 74, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned Reflexes; Dover Publications: Mineala, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.C.; Makous, W.; Button, R.A. Temporal parameters of conditioned hypoglycemia. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1969, 69, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vit, J.-P.; Fuchs, D.-T.; Angel, A.; Levy, A.; Lamensdorf, I.; Black, K.L.; Koronyo, Y.; Koronyo-Hamaoui, M. Visual-stimuli four-arm maze test to assess cognition and vision in mice. Bio Protoc. 2021, 11, e4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitz-James, M.H.; Cavalli, G. Molecular mechanisms of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendinning, J.I.; Frim, Y.G.; Hochman, A.; Lubitz, G.S.; Basile, A.J.; Sclafani, A. Glucose elicits cephalic-phase insulin release in mice by activating K(ATP) channels in taste cells. Am. J. Physiol. 2017, 312, R597–R610. [Google Scholar]

- Nisi, A.V.; Arnold, M.; Blonde, G.D.; Schier, L.A.; Sanchez-Watts, G.; Watts, A.G.; Langhans, W.; Spector, A.C. Sugar type and route of delivery influence insulin and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide responses in rats. Am. J. Physiol. (Endocrinol. Metab.) 2025, 329, E210–E225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, R.D. Physiological responses to sensory stimulation by food: Nutritional implications. J. Amer. Diet. Assoc. 1997, 97, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeets, P.A.M.; Erkner, A.; de Graaf, C. Cephalic phase responses and appetite. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.L.; Reilly, S.M. Health problems associated with international business travel: A critical review of the literature. AAOHN J. 2000, 8, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mittelman, L.; Ashkar, N.; Khwaja, F.; Resnick, C.; Glendinning, J.I. Mice Condition Cephalic Insulin Responses to the Flavor of Different Laboratory Chows. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243880

Mittelman L, Ashkar N, Khwaja F, Resnick C, Glendinning JI. Mice Condition Cephalic Insulin Responses to the Flavor of Different Laboratory Chows. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243880

Chicago/Turabian StyleMittelman, Laura, Natalie Ashkar, Fatima Khwaja, Clara Resnick, and John I. Glendinning. 2025. "Mice Condition Cephalic Insulin Responses to the Flavor of Different Laboratory Chows" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243880

APA StyleMittelman, L., Ashkar, N., Khwaja, F., Resnick, C., & Glendinning, J. I. (2025). Mice Condition Cephalic Insulin Responses to the Flavor of Different Laboratory Chows. Nutrients, 17(24), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243880