Redox Response in Postoperative Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: New Insights into Cardiovascular Risk Markers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

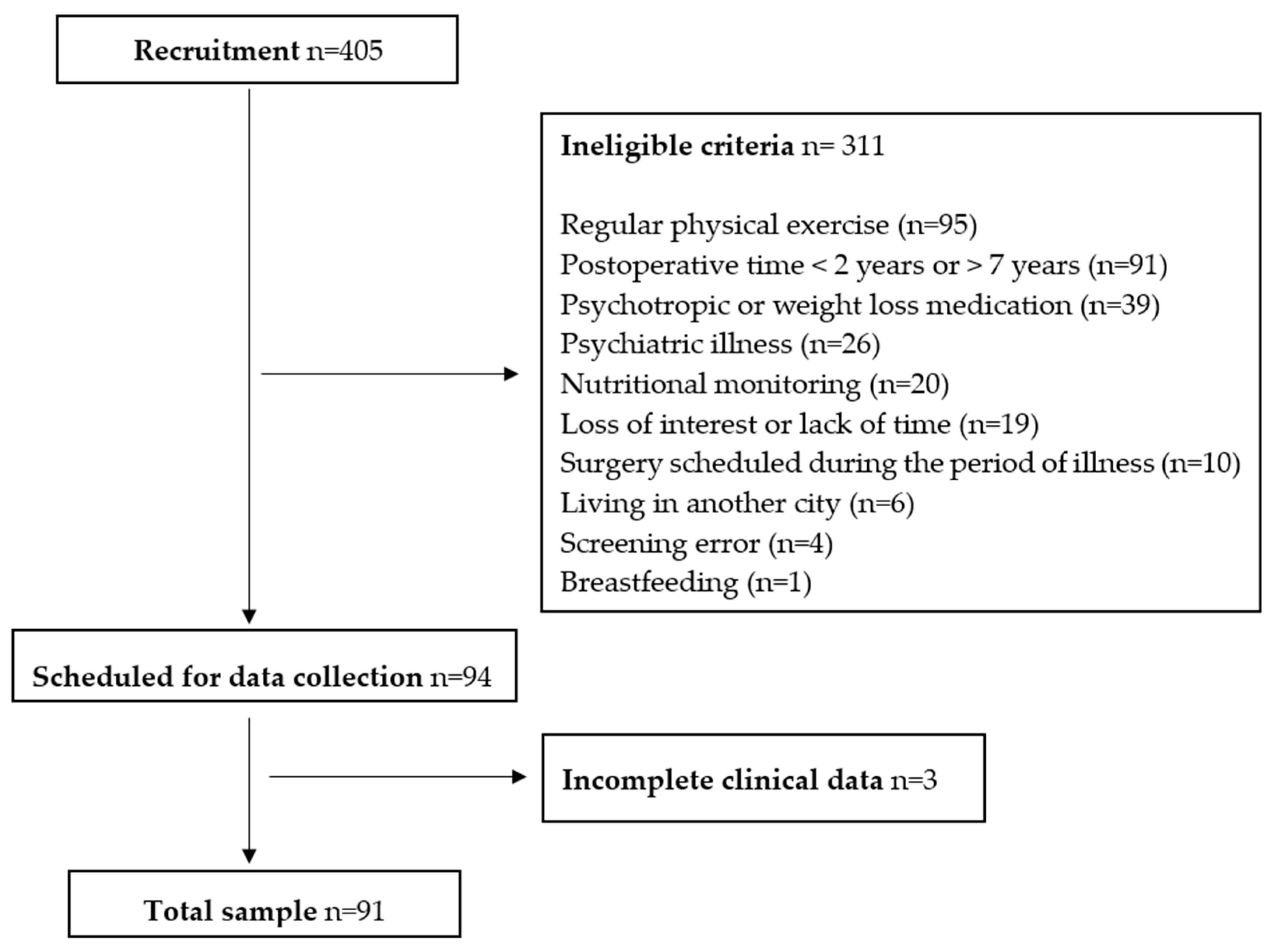

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sociodemographic Data

2.3. Clinical Measurements

2.4. Dietary Assessment

2.5. Biochemical Analyses

2.5.1. Biological Sample

2.5.2. Redox Response Biomarkers

Sample Homogenate

CAT Assay

GPx Assay

Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) Assay

SOD Assay

Oxidative Damage to Lipids

Oxidative Damage to Proteins

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MBS | Metabolic and bariatric surgery |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TBARSs | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| WR | Weight regain |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| dTAC | Total antioxidant capacity of the diet |

| TyG | Triglyceride/glucose index |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| Non-HDL-C | Non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC | Principal component |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GST | Glutathione-S-transferase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

References

- Yu, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, X.; Guo, W.; Sheng, M.; Gao, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Ma, X. Redox Biology in Adipose Tissue Physiology and Obesity. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, 2200234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masenga, S.K.; Kabwe, L.S.; Chakulya, M.; Kirabo, A. Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldo, A.M.; Soldo, I.; Karačić, A.; Konjevod, M.; Perkovic, M.N.; Glavan, T.M.; Luksic, M.; Žarković, N.; Jaganjac, M. Lipid Peroxidation in Obesity: Can Bariatric Surgery Help? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradel-Mora, J.J.; Marín, G.; Castillo-Rangel, C.; Hernández-Contreras, K.A.; Vichi-Ramírez, M.M.; Zarate-Calderon, C.; Motta, F.S.H. Oxidative Stress in Postbariatric Patients: A Systematic Literature Review Exploring the Long-term Effects of Bariatric Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2024, 12, E5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, Y.; Lou, Y.X.; Li, C.; Sun, J.Y.; Sun, W.; Kong, X.Q. Clinical outcomes of bariatric surgery—Updated evidence. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, C.M.; Cohen, R.V.; Sumithran, P.; Clément, K.; Frühbeck, G. Contemporary medical, device, and surgical therapies for obesity in adults. Lancet 2023, 401, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, S.L.; Juvanhol, L.L.; de Oliveira, L.L.; Clemente, R.C.; Bressan, J. Changes in oxidative stress markers and cardiometabolic risk factors among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients after 3- and 12-months postsurgery follow-up. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadalt, C.; Fagundes, R.L.M.; Moreira, E.A.M.; Wilhelm-Filho, D.; De Freitas, M.B.; Jordão Júnior, A.A.; Biscaro, F.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Vannucchi, H. Oxidative stress markers in adults 2 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 25, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, C.; Moreira, E.A.M.; de Freitas, M.B.; da Silva, A.F.; Portari, G.V.; Wilhelm Filho, D. Effect of RYGB on Oxidative Stress in Adults: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3301–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Li, W.; Song, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, S. Disease-specific mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events after bariatric surgery: A meta-analysis of age, sex, and BMI-matched cohort studies. Int. J. Surg. 2023, 109, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Elhag, W. Weight Regain and Insufficient Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: Definitions, Prevalence, Mechanisms, Predictors, Prevention and Management Strategies, and Knowledge Gaps—A Scoping Review. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiadis, D.I.; Martin, A.; Kapsampelis, P.; Monfared, S.; Stefanidis, D. Factors associated with weight regain post-bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 4069–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porat, T.; Mashin, L.; Kaluti, D.; Goldenshluger, A.; Shufanieh, J.; Khalaileh, A.; Gazala, M.A.; Mintz, Y.; Brodie, R.; Sakran, N.; et al. Weight Loss Outcomes and Lifestyle Patterns Following Sleeve Gastrectomy: An 8-Year Retrospective Study of 212 Patients. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 4836–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courcoulas, A.P.; Daigle, C.R.; Arterburn, D.E. Long term outcomes of metabolic/bariatric surgery in adults. BMJ 2023, 383, e071027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.C.; Hinerman, A.S.; Belle, S.H.; Wahed, A.S.; Courcoulas, A.P. Comparison of the Performance of Common Measures of Weight Regain after Bariatric Surgery for Association with Clinical Outcomes. JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirapinyo, P.; Dayyeh, B.K.A.; Thompson, C.C. Weight regain after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has a large negative impact on the Bariatric Quality of Life Index. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017, 4, e000153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courcoulas, A.P.; King, W.C.; Belle, S.H.; Berk, P.; Flum, D.R.; Garcia, L.; Gourash, W.; Horlick, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Pomp, A.; et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.C.; Hinerman, A.S.; Courcoulas, A.P. Weight regain after bariatric surgery: A systematic literature review and comparison across studies using a large reference sample. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariete Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 23, pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, C.T.; Freire, A.C.C.; Silva, A.P.B.; Teixeira, R.M.; Farrell, M.; Prince, M. Concurrent and construct validity of the audit in an urban Brazillian sample. Alcohol. Alcohol. 2005, 40, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. In Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; Volume 894. [Google Scholar]

- Muntner, P.; Shimbo, D.; Carey, R.M.; Charleston, J.B.; Gaillard, T.; Misra, S.; Myers, M.G.; Ogedegbe, G.; Schwartz, J.E.; Townsend, R.R.; et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2019, 73, e35–e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.M.; Ingwersen, L.A.; Vinyard, B.T.; Moshfegh, A.J. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and nonobese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barufaldi, L.A.; Abreu, G.D.A.; Veiga GVDa Sichieri, R.; Kuschnir, M.C.C.; Cunha, D.B.; Pereira, R.A.; Bloch, K.V. Programa para registro de recordatório alimentar de 24 horas: Aplicação no Estudo de Riscos Cardiovasculares em Adolescentes. Rev. Bras. De Epidemiol. 2016, 19, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harttig, U.; Haubrock, J.; Knüppel, S.; Boeing, H. The MSM program: Web-based statistics package for estimating usual dietary intake using the multiple source method. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, M.H.; Halvorsen, B.L.; Holte, K.; Bøhn, S.K.; Dragland, S.; Sampson, L.; Willey, C.; Senoo, H.; Umezono, Y.; Sanada, C.; et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Romero, F.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; González-Ortiz, M.; Martínez-Abundis, E.; Ramos-Zavala, M.G.; Hernández-González, S.O.; Jacques-Camarena, O.; Rodríguez-Morán, M. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 3347–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartree, E.F. Determination of Protein: A Modification of the Lowry Method That Gives a Linear Photometric Response. Anal. Biochem. 1972, 48, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanisse, D.R.; Storey, K.B. Oxidative damage and antioxidants in Rana sylvatica, the freeze-tolerant wood frog. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1996, 271, R545–R553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habig, W.H.; Jakoby, W.B. Assays for Differentiation of Glutathione S-Transferases. Methods Enzymol. 1981, 77, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCord, J.M. Analysis of Superoxide Dismutase Activity. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 1999, 1, 7.3.1–7.3.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasowicz, W.; Neve, J.; Peretz, A. Optimized steps in fluorometric determination of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances in serum: Importance of extraction pH and influence of sample preservation and storage. Clin. Chem. 1993, 39, 2522–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, C.S.; Oliveira, R.; Bento, F.; Geraldo, D.; Rodrigues, J.V.; Marcos, J.C. Simplified 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine spectrophotometric assay for quantification of carbonyls in oxidized proteins. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 458, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matés, J.M.; Pérez-Gómez, C.; De Castro, I.N. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clin. Biochem. 1999, 32, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Kang, P.M. A Systematic Review on Advances in Management of Oxidative Stress-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăgoi, C.M.; Diaconu, C.C.; Nicolae, A.C.; Dumitrescu, I.B. Redox Homeostasis and Molecular Biomarkers in Precision Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Wang, X.; An, P.; Luo, J.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, Y. Lipid Supplement on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormaz, J.G.; Carrasco, R. Antioxidant Supplementation in Cardiovascular Prevention: New Challenges in the Face of New Evidence. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2286–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, P.; Wan, S.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, S.; Xu, T.; He, J.; Mechanick, J.I.; Wu, W.C.; et al. Micronutrient Supplementation to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2269–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox system in health and disease: The latest update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boura-Halfon, S.; Zick, Y. Phosphorylation of IRS proteins, insulin action, and insulin resistance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 29, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griendling, K.K.; Camargo, L.L.; Rios, F.J.; Alves-Lopes, R.; Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Oxidative Stress and Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 993–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, M.; Capatti, E.; Borghi, C.; Zuliani, G. Serum Malondialdehyde Levels in Hypertensive Patients: A Non-invasive Marker of Oxidative Stress. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2022, 29, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, N.; Zaidi, I.A.; Kamal, Z.; Khan, R.U. Estimation of Serum Malondialdehyde (a Marker of Oxidative Stress) as a Predictive Biomarker for the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e69756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Shangguan, Q.; Xie, G.; Sheng, G.; Yang, J. Oxidative stress mediates the association between triglyceride-glucose index and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in metabolic syndrome: Evidence from a prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1452896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepys, M.B.; Hirschfield, G.M. C-reactive protein: A critical update. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Kostara, C.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Salamou, E.; Guzman, E. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černiauskas, L.; Mažeikienė, A.; Mazgelytė, E.; Petrylaitė, E.; Linkevičiūtė-Dumčė, A.; Burokienė, N.; Karčiauskaitė, D. Malondialdehyde, Antioxidant Defense System Components and Their Relationship with Anthropometric Measures and Lipid Metabolism Biomarkers in Apparently Healthy Women. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I.; et al. Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 552535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biomarkers | Analytical Methods | Measurement Units |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant response | ||

| Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) | Spectrophotometry | U/mg protein |

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | Spectrophotometry | U/mg protein |

| Catalase (CAT) | Spectrophotometry | U/mg protein |

| GPx (Glutathione Peroxidase) | Spectrophotometry | U/mg protein |

| Oxidative Damage | ||

| Carbonyl protein | Spectrophotometry | nmol/mg protein |

| Malondialdehyde (MDA) | Fluorimetry | nmol/mL |

| Variables | All (n = 91) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Female (n/%) | 84 (92.31) |

| Age (years) | 39.82 ± 7.87 |

| Educational level (years) | 13 ± 2.3 |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Postoperative time (years) | 3.95 ± 1.48 |

| Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (n/%) | 86 (94.51) |

| Sleeve gastrectomy (n/%) | 5 (5.49) |

| Preoperative body mass index (kg/m2) | 42.09 ± 5.64 |

| Current body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.53 ± 5.01 |

| Excess Weight Loss (%) | 76.75 ± 25.07 |

| Total Weight Loss (%) | 44.44 ± 18.81 |

| Weight regain (%) | 54 (59.34) |

| Self-reported postoperative comorbidities a (n/%) | 16 (17.58) |

| Self-reported sedentary lifestyle (n/%) | 80 (87.91) |

| Smoking (n/%) | 5 (5.49) |

| High risk of alcohol use disorder b (n/%) | 23 (25.27) |

| Supplements—Multivitamins (n/%) | 65 (71.43) |

| Supplements—Omega-3 (n/%) | 16 (17.58) |

| Supplements—Iron (n/%) | 28 (30.77) |

| dTAC c (mmol Fe/1000 kcal) | 5.30 ± 3.36 |

| Redox response | |

| Antioxidant response | |

| GST d (U/mg protein) | 3.47 ± 1.53 |

| SOD e (U/mg protein) | 8.48 ± 3.43 |

| CAT f (U/mg protein) | 112.14 ± 20.45 |

| GPx g (U/mg protein) | 31.99 ± 11.86 |

| Oxidative Damage | |

| Carbonyl (nmol/mg protein) | 1.26 ± 0.29 |

| MDA h (nmol/mL) | 10.85 ± 2.15 |

| Latent/Observed Variables | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| Redox response | ||

| GST (U/mg protein) | 0.4277 | |

| SOD (U/mg protein) | 0.4670 | |

| CAT (U/mg protein) | 0.5758 | |

| GPx (U/mg protein) | 0.5031 | |

| Carbonyl (nmol/mg protein) | 0.3314 | |

| MDA (nmol/mL) | 0.7757 | |

| Eigenvalue | 1.74 | 1.20 |

| Variance explained (%) | 29.08 | 20.00 |

| Cumulative explained variance (%) | 29.08 | 49.08 |

| Variables | Total Sample | PC1 Score Below Median | PC1 Score Above Median | p-Value * | PC2 Score Below Median | PC2 Score Above Median | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Composition | |||||||

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 49.78 ± 8.22 | 49.52 ± 8.72 | 50.05 ± 7.76 | 0.47 | 50.16 ± 8.54 | 49.39 ± 7.95 | 0.58 |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) | 27.22 ± 4.90 | 27.04 ± 5.17 | 27.41 ± 4.65 | 0.43 | 27.36 ± 5.15 | 27.07 ± 4.68 | 0.82 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 30.47 ± 11.57 | 30.21 ± 11.44 | 30.74 ± 11.8 | 0.81 | 31.01 ± 13.03 | 29.93 ± 9,98 | 0.99 |

| Body fat (%) | 36.93 ± 7.80 | 36.95 ± 7.58 | 36.91 ± 8.10 | 0.77 | 36.89 ± 8.41 | 36.97 ± 7.22 | 0.90 |

| VAT (cm2) a | 118.83 ± 35.94 | 118.42 ± 36.30 | 119.23 ± 35.98 | 0.81 | 117.92 ± 36.92 | 119.73 ± 35.33 | 0.82 |

| Cardiovascular risk | |||||||

| SBP (mmHg) b | 113.46 ± 16.67 | 115.81 ± 19.56 | 111.11 ± 12.98 | 0.30 | 109.95 ± 12.86 | 117.14 ± 19.38 | 0.09 |

| DBP (mmHg) c | 75.82 ± 11.95 | 78.18 ± 12.61 | 73.45 ± 10.89 | 0.06 | 72.50 ± 9.19 | 79.29 ± 13.54 | 0.02 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 80.16 ± 6.79 | 81.17 ± 5.46 | 79.13 ± 7.85 | 0.09 | 80.30 ± 5.94 | 80.02 ± 7.62 | 0.73 |

| Basal insulin (µU/L) | 6.42 ± 4.91 | 6.31 ± 3.96 | 6.54 ± 5.76 | 0.74 | 6.26 ± 4.15 | 6.59 ± 5.62 | 0.85 |

| HbA1c (%) d | 5.40 ± 0.34 | 5.39 ± 0.32 | 5.41 ± 0.36 | 0.87 | 5.40 ± 0.35 | 5.40 ± 0.33 | 0.72 |

| HOMA-IR e | 1.29 ± 1.03 | 1.27 ± 0.87 | 1.30 ± 1.18 | 0.57 | 1.24 ± 0.89 | 1.33 ± 1.17 | 0.94 |

| TyG index f | 4.30 ± 0.21 | 4.31 ± 0.19 | 4.30 ± 0.23 | 0.43 | 4.24 ± 0.16 | 4.38 ± 0.24 | 0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 158.98 ± 28.98 | 159.30 ± 28.24 | 158.64 ± 30.03 | 0.68 | 151.48 ± 27.40 | 166.64 ± 28.83 | 0.008 |

| TG (mg/dL) g | 75.32 ± 43.84 | 72.89 ± 28.93 | 77.80 ± 55.34 | 0.85 | 62.52 ± 17.33 | 88.40 ± 57.25 | 0.005 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) h | 89.13 ± 25.91 | 90.41 ± 25.40 | 87.82 ± 26.6 | 0.58 | 86.02 ± 25.89 | 92.31 ± 25.83 | 0.24 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) i | 56.16 ± 14.48 | 55.52 ± 12.87 | 56.82 ± 16.08 | 0.92 | 53.72 ± 12.97 | 58.67 ± 15.62 | 0.13 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) j | 103.15 ± 27.02 | 104.39 ± 26.79 | 101.89 ± 27.49 | 0.51 | 97.74 ± 25.72 | 108.69 ± 27.47 | 0.05 |

| CRP (mg/L) k | 1.51 ± 3.64 | 1.45 ± 4.41 | 1.58 ± 2.69 | 0.02 | 0.78 ± 1.13 | 2.26 ± 4.97 | 0.20 |

| Variables | PC1 a | PC2 b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Model c | Model 1 d | Model 2 e | Crude Model c | Model 1 d | Model 2 e | |

| Coefficient β (95% CI) | Coefficient β (95% CI) | |||||

| <median scores | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) | (ref.) |

| SBP (mmHg) f | −4.70 (−11.64; 2.23) | −3.96 (−10.69; 2.77) | −4.08 (−10.80; 2.63) | 7.18 (0.34; 14.03) * | 6.19 (−0.53; 12.92) | 5.98 (−0.76; 12.71) |

| DPB (mmHg) g | −4.73 (−9.65; 0.20) | −4.18 (−9.02; 0.66) | −4.29 (−9.11; 0.52) | 6.79 (1.97; 11.61) * | 6.48 (1.71; 11.26) * | 6.30 (1.53; 11.07) * |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | −2.04 (−4.81; 0.73) | −1.92 (−4.70; 0.86) | −1.91 (−4.66; 0.84) | −0.28 (−3.08; 2.52) | −0.30 (−3.14; 2.54) | −0.09 (−2.91; 2.73) |

| Basal insulin (µU/L) | 0.23 (−1.80; 2.25) | −0.17 (−2.13; 1.78) | −0.18 (−2.14; 1.79) | 0.33 (−1.69; 2.36) | 0.57 (−1.42; 2.53) | 0.50 (−1.49; 2.50) |

| HbA1c (%) h | 0.01 (−0.12; 0.16) | 0.004 (−0.12; 0.13) | 0.004 (−0.13; 0.13) | 0.002 (−0.14; 0.14) | 0.04 (−0.09; 0.17) | 0.04 (−0.09; 0.17) |

| HOMA-IR i | 0.03 (−0.40; 0.45) | −0.05 (−0.47; 0.36) | −0.05 (−0.47; 0.36) | 0.08 (−0.34; 0.51) | 0.13 (−0.28; 0.55) | 0.12 (−0.30; 0.55) |

| TyG j | −0.007 (−0.09; 0.08) | −0.008 (−0.10; 0.08) | −0.008 (−0.10; 0.08) | 0.13 (0.05; 0.21) * | 0.13 (0.05; 0.22) * | 0.13 (0.05; 0.22) * |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.66 (−12.63; 11.31) | 0.71 (−10.28; 11.69) | 0.75 (−10.12; 11.62) | 15.17 (3.61; 26.72) * | 13.79 (3.07; 24.51) * | 14.69 (4.11; 25.28) * |

| TG (mg/dL) k | 4.91 (−13.18; 23.00) | 4.07 (−14.04; 22.19) | 4.08 (−14.14; 22.30) | 25.88 (8.58; 43.18) * | 26.58 (9.13; 44.04) * | 26.95 (9.34; 44.55) * |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) l | −2.59 (−13.28; 8.10) | −2.14 (−12.31; 8.02) | −2.12 (−12.26; 8.03) | 6.29 (−4.34; 16.92) | 4.90 (−5.35; 15.14) | 5.46 (−4.78; 15.71) |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) m | 1.30 (−4.68; 7.28) | 2.13 (−3.50; 7.76) | 2.14 (−3.52; 7.80) | 4.95 (−0.94; 10.84) | 5.23 (−0.37; 10.84) | 5.39 (−0.26; 11.04) |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) n | −2.50 (−13.66; 8.65) | −2.08 (−12.51; 8.34) | −2.05 (−12.40; 8.31) | 10.91 (0.02; 21.88) * | 9.56 (−0.79; 19.92) | 10.30 (0.01; 20.59) * |

| CRP (mg/L) o | 0.12 (−1.38; 1.63) | −0.002 (−1.52; 1.52) | −0.007 (−1.52; 1.51) | 1.48 (0.01; 2.95) * | 1.39(−0.12; 2.90) | 1.31 (−0.20; 2.82) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maia, R.P.; Arruda, S.F.; do Carmo, A.S.; Botelho, P.B.; de Carvalho, K.M.B. Redox Response in Postoperative Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: New Insights into Cardiovascular Risk Markers. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243821

Maia RP, Arruda SF, do Carmo AS, Botelho PB, de Carvalho KMB. Redox Response in Postoperative Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: New Insights into Cardiovascular Risk Markers. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243821

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaia, Ruanda Pereira, Sandra Fernandes Arruda, Ariene Silva do Carmo, Patrícia Borges Botelho, and Kênia Mara Baiocchi de Carvalho. 2025. "Redox Response in Postoperative Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: New Insights into Cardiovascular Risk Markers" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243821

APA StyleMaia, R. P., Arruda, S. F., do Carmo, A. S., Botelho, P. B., & de Carvalho, K. M. B. (2025). Redox Response in Postoperative Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: New Insights into Cardiovascular Risk Markers. Nutrients, 17(24), 3821. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243821