The Olive Phenolic S–(–)–Oleocanthal as a Novel Intervention for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancers: Therapeutic and Molecular Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.3. NCI-H660 Cell Transfection

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

2.5. Lentivirus-Aided Luciferase Labeling of NCI-H660 Cells

2.6. Tissue Microarray Immunohistochemistry and Histochemical Score

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

2.8. RNA Extraction

2.9. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

2.10. Animal Models and Treatments

2.11. Nude Mouse Xenograft Model

2.12. LuCaP 93 PDX Transplanted in an NSG Mice Model

2.13. RNA Sequencing and Data Analysis

2.14. Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA)

2.15. Protein–Protein Interactions

2.16. Statistics

3. Results

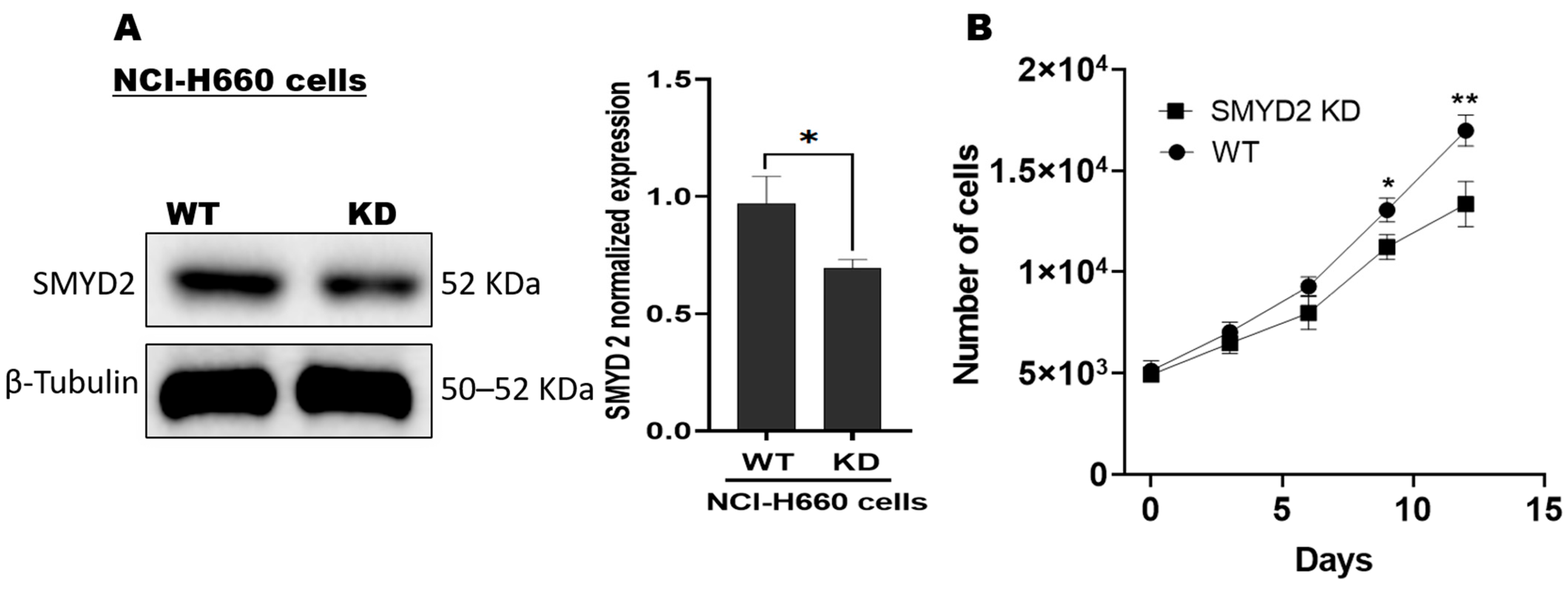

3.1. SMYD2 Is a Contributing Factor for NCI-H660 De Novo NEPC Cell Survival

3.2. OC Attenuated NCI-H660 Cell Proliferation and Suppressed SMYD2 Expression

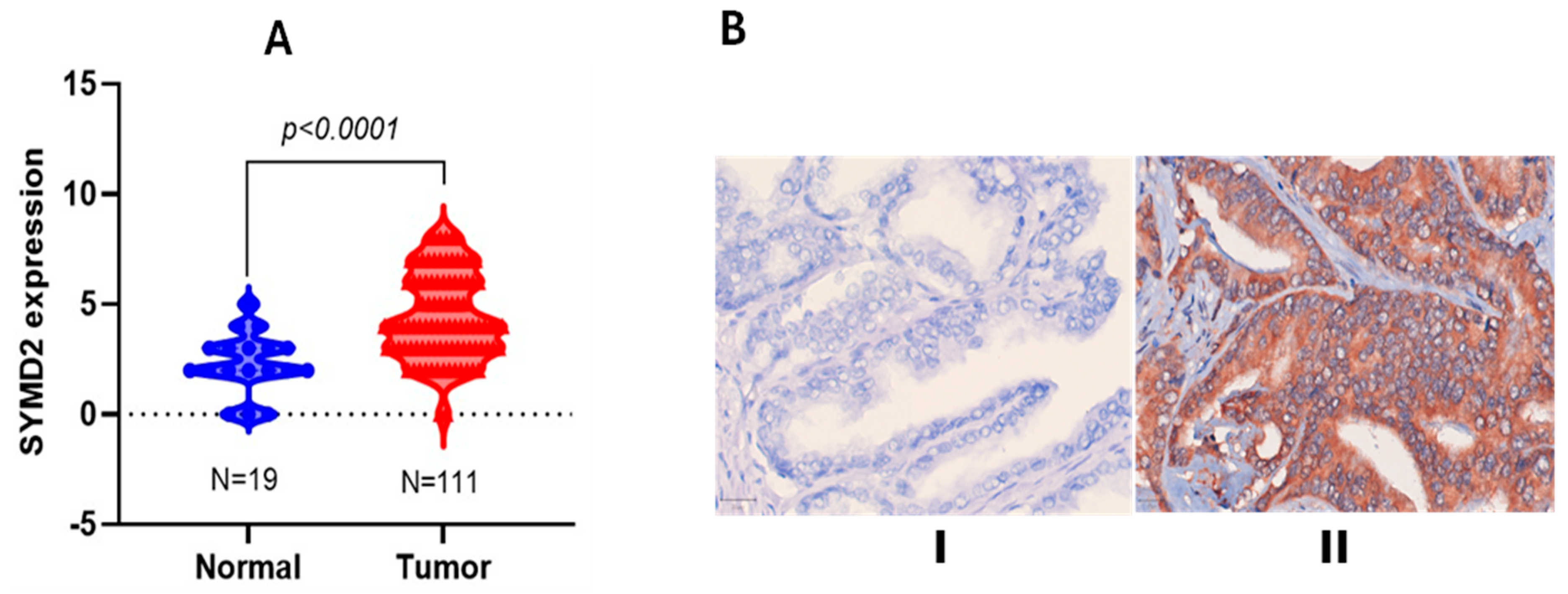

3.3. Differential SMYD2 Expression in PCa Versus Non-Tumorigenic Prostate Tissues

3.4. Daily Oral OC Treatments Suppressed the De Novo NEPC Progression and Recurrence and t-NEPC PDX Progression

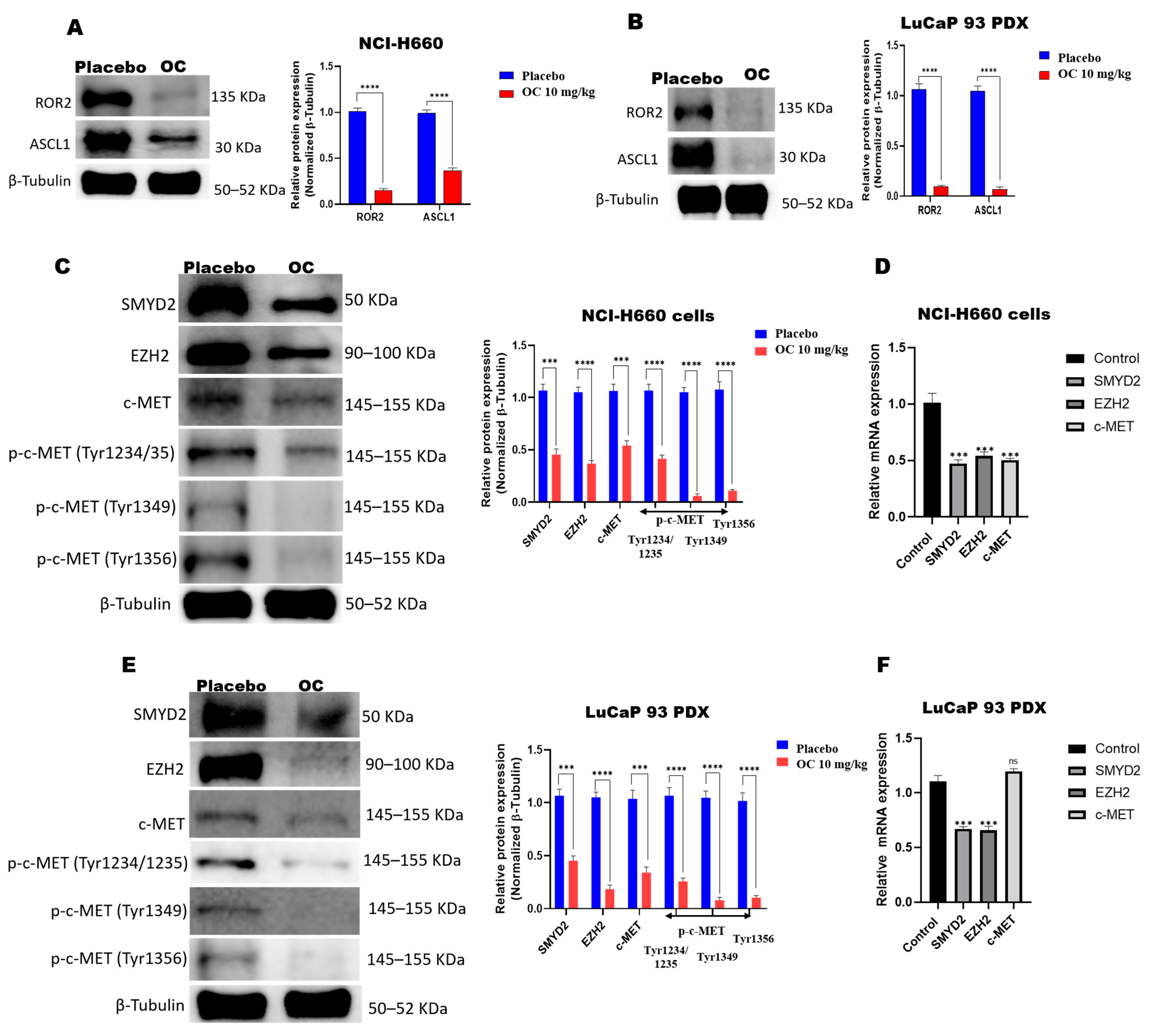

3.5. OC Downregulates ROR2-ASCL1, SMYD2-EZH2, and c-MET in NCI-H660-Luc Cell Primary Tumors and LuCaP 93 PDX Model

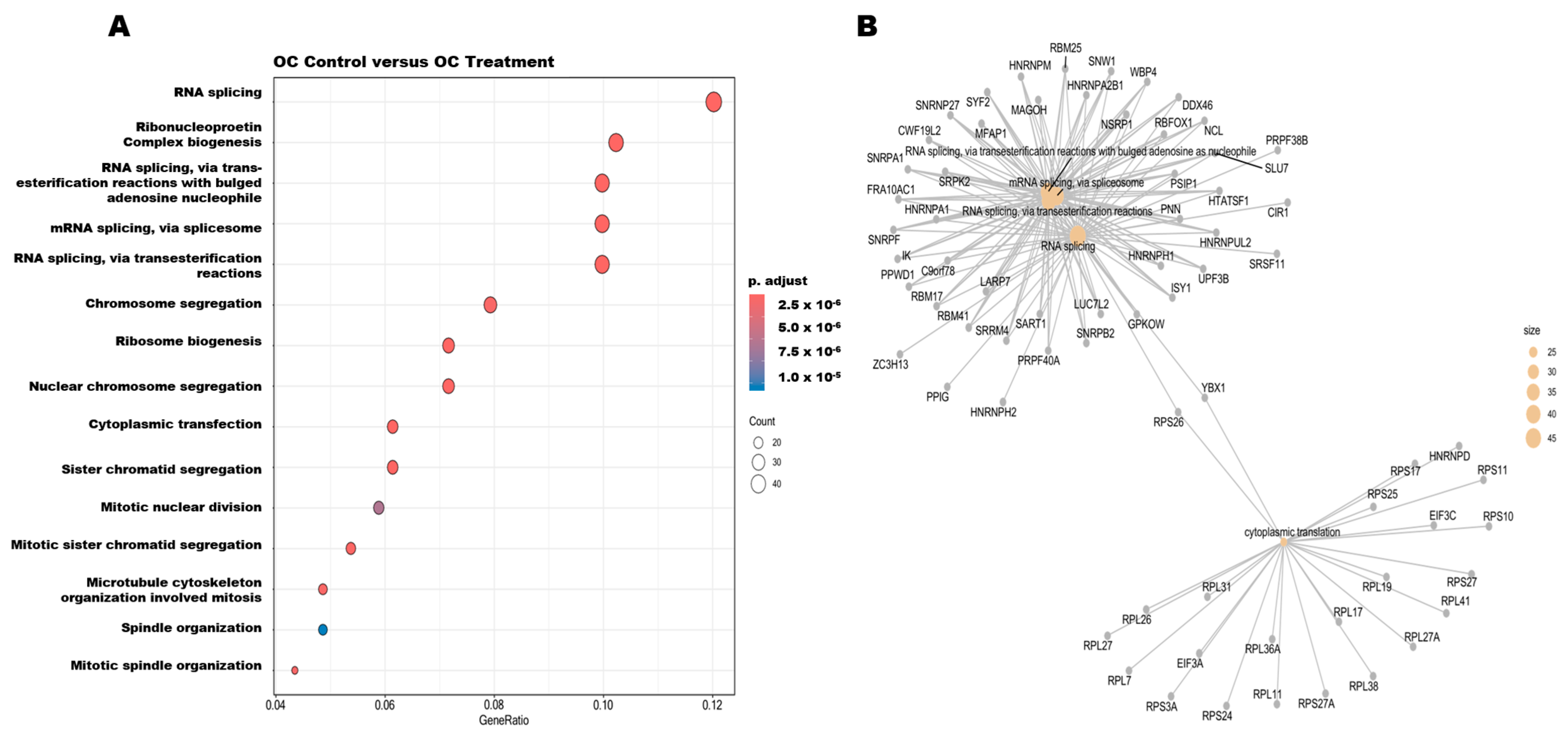

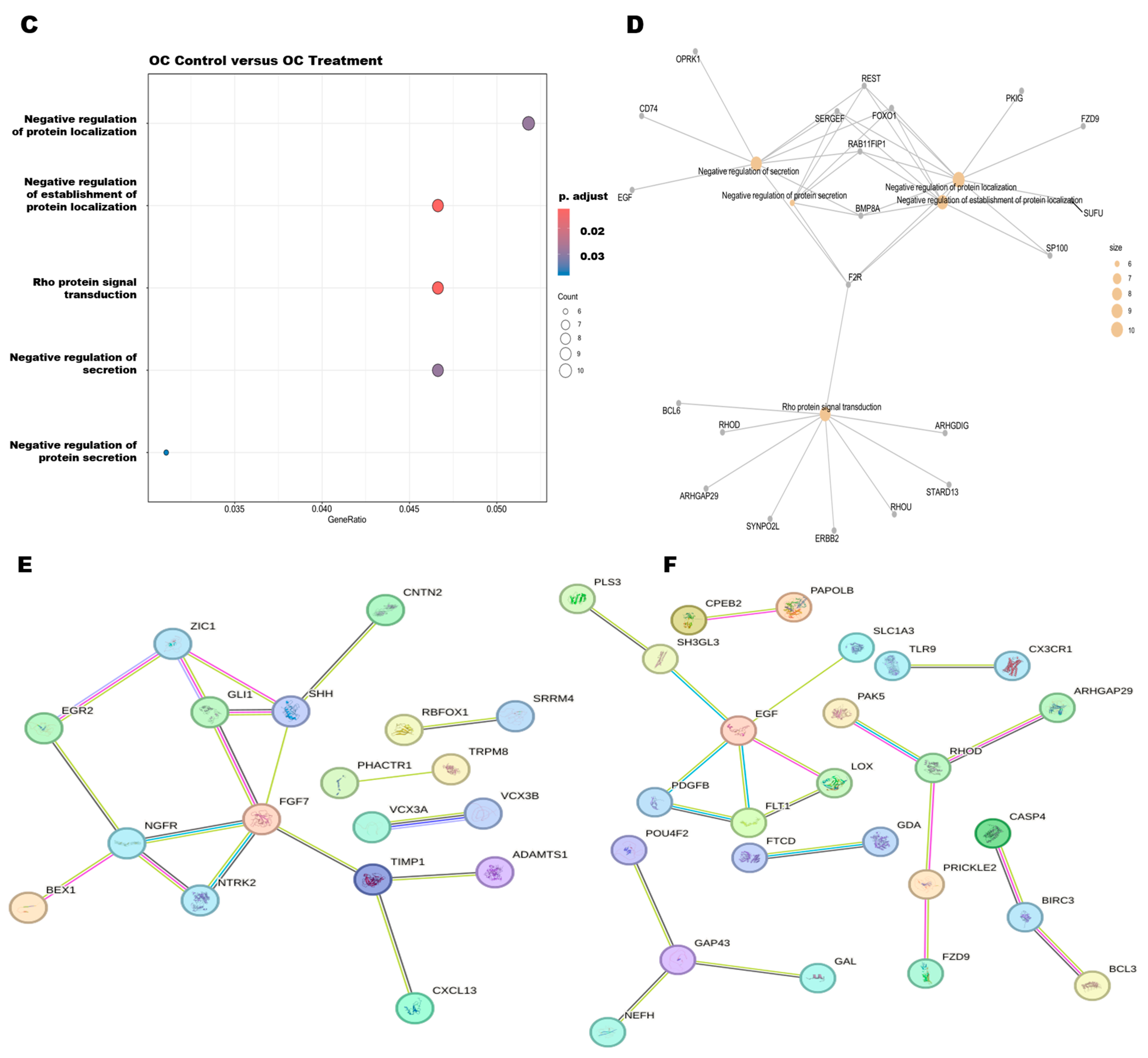

3.6. Pathway Enrichment Analysis and Protein–Protein Interactions of DEGs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Prostate Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/prostate-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Dai, C.; Dehm, S.M.; Sharifi, N. Targeting the androgen signaling axis in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4267–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellky, J.E.; Ricke, W.A. Development and prevalence of castration-resistant prostate cancer subtypes. Neoplasia 2020, 22, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cheng, D.; Li, P. Androgen receptor dynamics in prostate cancer: From disease progression to treatment resistance. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1542811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shi, M.; Chuen Choi, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, D.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Y. Genomic alterations in neuroendocrine prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJUI Compass 2023, 4, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liang, X.; Wu, D.; Chen, S.; Yang, B.; Mao, W.; Shen, D. Clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes in neuroendocrine prostate cancer: A population-based study. Medicine 2021, 100, e25237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Beltran, H. Clinical and biological features of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eule, C.J.; Hu, J.; Al-Saad, S.; Collier, K.; Boland, P.; Lewis, A.R.; McKay, R.R.; Narayan, V.; Bosse, D.; Mortazavi, A.; et al. Outcomes of second-line therapies in patients with metastatic de novo and treatment-emergent neuroendocrine prostate cancer: A multi-institutional study. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2023, 21, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debebe, Z.; Rathmell, W.K. Ror2 as a therapeutic target in cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 150, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodarte, K.E.; Nir Heyman, S.; Guo, L.; Flores, L.; Savage, T.K.; Villarreal, J.; Deng, S.; Xu, L.; Shah, R.B.; Oliver, T.G.; et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer requires ASCL1. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3522–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirich, S.; Schuhmacher, M.K.; Kudithipudi, S.; Lungu, C.; Ferguson, A.D.; Jeltsch, A. Analysis of the substrate specificity of the SMYD2 protein lysine methyltransferase and discovery of novel non-histone substrates. Chembiochem 2020, 21, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, S.; Imoto, I.; Tsuda, H.; Kozaki, K.I.; Muramatsu, T.; Shimada, Y.; Aiko, S.; Yoshizumi, Y.; Ichikawa, D.; Otsuji, E.; et al. Overexpression of SMYD2 relates to tumor cell proliferation and malignant outcome of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S.; Kim, D.S.; Son, M.Y.; Cho, H.S. SMYD family in cancer: Epigenetic regulation and molecular mechanisms of cancer proliferation, metastasis, and drug resistance. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Song, J.; Yan, Y.; Ren, Z.; et al. SMYD2 suppresses APC2 expression to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 997. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.X.; Zhou, J.X.; Calvet, J.P.; Godwin, A.K.; Jensen, R.A.; Li, X. Lysine methyltransferase SMYD2 promotes triple negative breast cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, S.; Wan, F.; Liu, Z.; Dai, B. Lysine methyltransferase SMYD2 enhances androgen receptor signaling to modulate CRPC cell resistance to enzalutamide. Oncogene 2024, 43, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.I.; Qiu, R.; Yang, Y.; Gao, T.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, K.; Liu, R.; Wang, S.; et al. Regulation of EZH2 by SMYD2-mediated lysine methylation is implicated in tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Shankar, E.; Gupta, S. EZH2-mediated development of therapeutic resistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024, 586, 216706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkaris, A.; Corn, P.G.; Gaur, S.; Dayyani, F.; Logothetis, C.J.; Gallick, G.E. The role of HGF/c-Met signaling in prostate cancer progression and c-Met inhibitors in clinical trials. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2011, 20, 1677–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentella, M.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Ricci, C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miggiano, G.A.D. Cancer and Mediterranean diet: A review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haouari, M.; Quintero, J.E.; Rosado, J.A. Anticancer molecular mechanisms of oleocanthal. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2820–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnagar, A.Y.; Sylvester, P.W.; El Sayed, K.A. (–)–Oleocanthal as a c-Met inhibitor for the control of metastatic breast and prostate cancers. Planta Medica 2011, 77, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qusa, M.H.; Abdelwahed, K.S.; Siddique, A.B.; El Sayed, K.A. Comparative gene signature of (–)–oleocanthal formulation treatments in heterogeneous triple negative breast tumor models: Oncological therapeutic target insights. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.B.; Ayoub, N.M.; Tajmim, A.; Meyer, S.A.; Hill, R.A.; El Sayed, K.A. (–)–Oleocanthal prevents breast cancer locoregional recurrence after primary tumor surgical excision and neoadjuvant targeted therapy in orthotopic nude mouse models. Cancers 2019, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.B.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; Tajmim, A.; King, J.A.; Abdelwahed, K.S.; Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; El Sayed, K.A. Oleocanthal attenuates metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progression and recurrence by targeting SMYD2. Cancers 2022, 14, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarun, M.T.I.; Elsayed, H.E.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; El Sayed, K.A. The olive oil phenolic S–(–)–oleocanthal suppresses colorectal cancer progression and recurrence by modulating SMYD2-EZH2 and c-MET activation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, A.B.; Ebrahim, H.; Mohyeldin, M.; Qusa, M.; Batarseh, Y.; Fayyad, A.; Tajmim, A.; Nazzal, S.; Kaddoumi, A.; El Sayed, K. Novel liquid-liquid extraction and self-emulsion methods for simplified isolation of extra-virgin olive oil phenolics with emphasis on (–)–oleocanthal and its oral anti-breast cancer activity. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, K.S.; Siddique, A.B.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; Qusa, M.H.; Mudhish, E.A.; Rad, A.H.; Zerfaoui, M.; Abd Elmageed, Z.Y.; El Sayed, K.A. Pseurotin A validation as a metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer recurrence-suppressing lead via PCSK9-LDLR axis modulation. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general-purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimand, J.; Isserlin, R.; Voisin, V.; Kucera, M.; Tannus-Lopes, C.; Rostamianfar, A.; Wadi, L.; Meyer, M.; Wong, J.; Xu, C.; et al. Pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of omics data using g: Profiler, GSEA, Cytoscape and EnrichmentMap. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 482–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.I.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellosaurus NCI-H660 (CVCL_1576). Available online: https://www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_1576 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Li, J.; Wan, F.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Y.; Hong, Z.; Dai, B. Targeting SMYD2 inhibits prostate cancer cell growth by regulating c-Myc signaling. Mol. Carcinog. 2023, 62, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tomás, T. Novel insights into SMYD2 and SMYD3 inhibitors: From potential anti-tumoural therapy to a variety of new applications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 7499–7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkadakrishnan, V.B.; Presser, A.G.; Singh, R.; Booker, M.A.; Traphagen, N.A.; Weng, K.; Voss, N.C.; Mahadevan, N.R.; Mizuno, K.; Puca, L.; et al. Lineage-specific canonical and non-canonical activity of EZH2 in advanced prostate cancer subtypes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, F.; Koinuma, D.; Shinozaki-Ushiku, A.; Fukayama, M.; Miyaozono, K.; Ehata, S. EZH2 promotes progression of small cell lung cancer by suppressing the TGF-β-Smad-ASCL1 pathway. Cell Discov. 2015, 1, 15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.A.; Dhele, N.; Cheemadan, S.; Ketkar, A.; Jayandharan, G.R.; Palakodeti, D.; Rampalli, S. Ezh2 mediated H3K27me3 activity facilitates somatic transition during human pluripotent reprogramming. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Niu, H.; Chen, L.; Lan, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. HGF/c-Met promotes breast cancer tamoxifen resistance through the EZH2/HOTAIR-miR-141/200a feedback signaling pathway. Mol. Carcinog. 2025, 64, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Wang, Q.; Huang, Y.; Petersen, R.B.; Liu, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Loss of histone lysine methyltransferase EZH2 confers resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, 495, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.B.; King, J.A.; Meyer, S.A.; Abdelwahed, K.; Busnena, B.; El Sayed, K. Safety evaluations of single dose of the olive secoiridoid S–(–)–oleocanthal in Swiss albino mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.; Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Alkhalifa, A.E.; Woodie, L.N.; Swinford, S.P.; King, J.; Greene, M.W.; Kaddoumi, A. Dose-dependent evaluation of chronic oleocanthal on metabolic phenotypes and organ toxicity in 5xFAD mice. Pharmacol. Res. Nat. Prod. 2025, 8, 100357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarun, M.T.I.; Ebrahim, H.Y.; Dawud, D.; Elmageed, Z.Y.A.; Corey, E.; El Sayed, K.A. The Olive Phenolic S–(–)–Oleocanthal as a Novel Intervention for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancers: Therapeutic and Molecular Insights. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243947

Tarun MTI, Ebrahim HY, Dawud D, Elmageed ZYA, Corey E, El Sayed KA. The Olive Phenolic S–(–)–Oleocanthal as a Novel Intervention for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancers: Therapeutic and Molecular Insights. Nutrients. 2025; 17(24):3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243947

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarun, Md Towhidul Islam, Hassan Y. Ebrahim, Dalal Dawud, Zakaria Y. Abd Elmageed, Eva Corey, and Khalid A. El Sayed. 2025. "The Olive Phenolic S–(–)–Oleocanthal as a Novel Intervention for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancers: Therapeutic and Molecular Insights" Nutrients 17, no. 24: 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243947

APA StyleTarun, M. T. I., Ebrahim, H. Y., Dawud, D., Elmageed, Z. Y. A., Corey, E., & El Sayed, K. A. (2025). The Olive Phenolic S–(–)–Oleocanthal as a Novel Intervention for Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancers: Therapeutic and Molecular Insights. Nutrients, 17(24), 3947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17243947