Do Physical Activity and Diet Independently Account for Variation in Body Fat in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review Unpacking the Roles of Exercise and Diet in Childhood Obesity

Abstract

1. Introduction

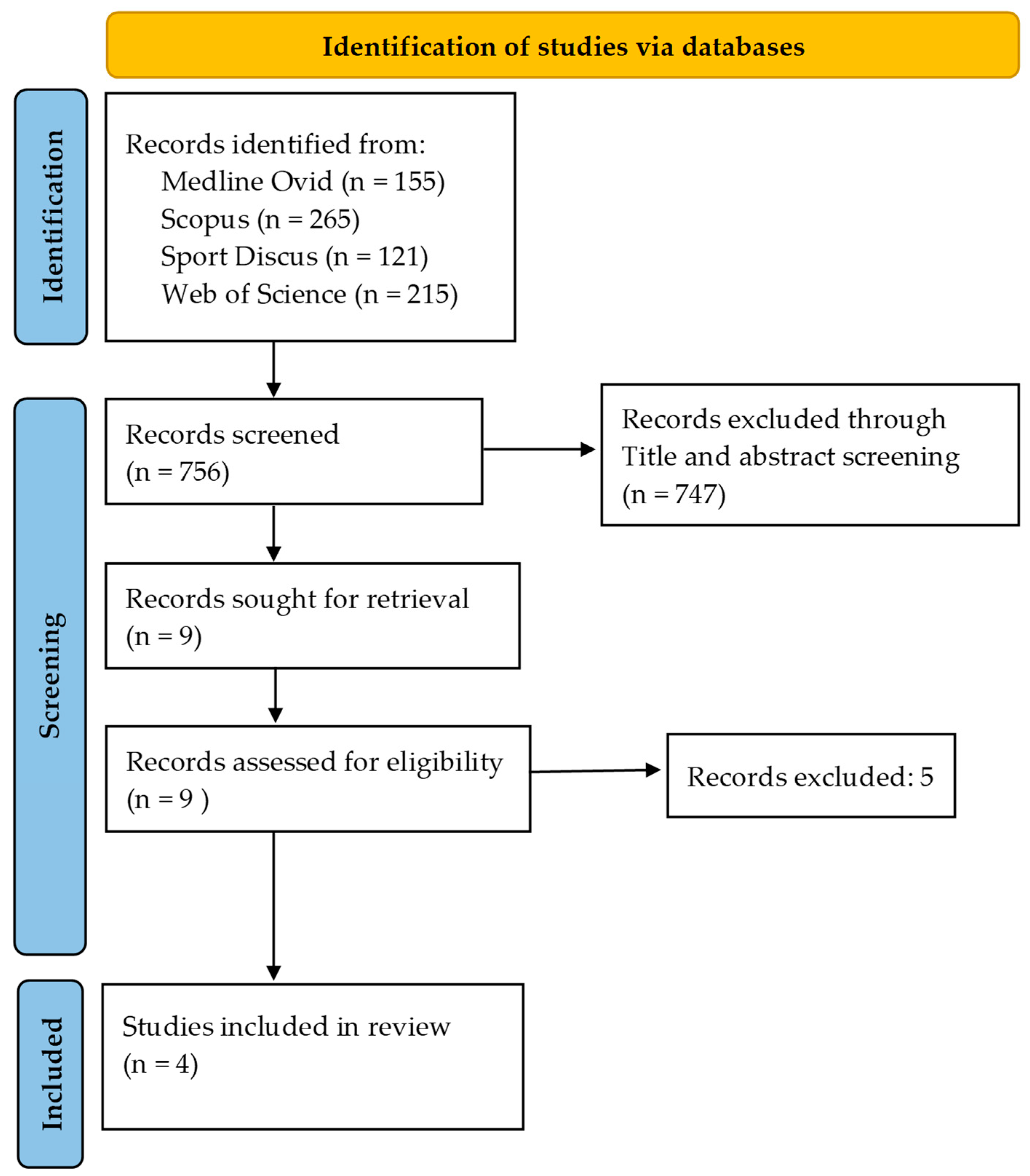

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Summary of Findings from Each Qualified Study (Listed Chronologically)

3.1.1. The LOOK Pre-Adolescence Study

3.1.2. The Helena/European Youth Heart Study (EYHS)

3.1.3. The Iowa Bone Development Study

3.1.4. The LOOK Adolescence Study

4. Discussion

4.1. Review Outcomes

4.2. Contrasts with Popular Opinion

4.3. Speculation from an Evolutionary Viewpoint

4.4. Is the Null Relationship Correct or Are EI Measures Inadequate?

4.5. Other Methodological Challenges

4.6. Community Campaigns

4.7. Limitations and Strengths

4.8. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical activity |

| EI | Energy intake |

| DEXA | Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry |

| EYHS | European Youth Heart Study |

| BIA | Bio-electrical impedance analysis |

References

- Lister, N.B.; Baur, L.A.; Felix, J.F.; Hill, A.J.; Marcus, C.; Reinehr, T.; Summerbell, C.; Wabitsch, M. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasim, A.; Turcotte, M.; de Souza, R.J.; Samaan, M.C.; Champredon, D.; Dushoff, J.; Speakman, J.R.; Meyre, D. On the origin of obesity: Identifying the biological, environmental and cultural drivers of genetic risk among human populations. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobstein, T.; Jackson-Leach, R.; Moodie, M.L.; Hall, K.D.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Swinburn, B.A.; James, W.P.T.; Wang, Y.; McPherson, K. Child and adolescent obesity: Part of a bigger picture. Lancet 2015, 385, 2510–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.A.; Patton, G.C.; Cini, K.I.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbas, N.; Abd Al Magied, A.H.; Abd El Hafeez, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdoun, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of child and adolescent overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, H.L.; Peeters, A.; Proietto, J.; McNeil, J.J. Public health campaigns and obesity—A critique. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, R.D.; Cunningham, R.B.; Abhayaratna, W. Temporal divergence of percent body fat and body mass index in pre-teenage children: The LOOK longitudinal study. Pediatr. Obes. 2014, 9, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, R.D.; Telford, R.M.; Welvaert, M. BMI is a misleading proxy for adiposity in longitudinal studies with adolescent males: The Australian LOOK study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, R.D.; Cunningham, R.B.; Telford, R.M.; Riley, M.; Abhayaratna, W.P. Determinants of childhood adiposity: Evidence from the Australian LOOK study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hands, B.; Parker, H.; Glasson, C.; Brinkman, S.; Read, H. Results of Western Australian Child and Adolescent Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey 2003 (CAPANS. Physical Activity Technical Report); The University of Notre Dame: Fremantle, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-García, M.; Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Labayen, I.; Moreno, L.A.; Patterson, E.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; González-Gross, M.; Marcos, A.; Polito, A.; et al. More physically active and leaner adolescents have higher energy intake. J. Pediatr. 2014, 164, 159–166.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Janz, K.F.; Letuchy, E.M.; Burns, T.L.; Levy, S.M. Active lifestyle in childhood and adolescence prevents obesity development in young adulthood. Obesity 2015, 23, 2462–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, G.; Black, A.; Jebb, S.; Cole, T.; Murgatroyd, P.; Coward, W.; Prentice, A. Critical evaluation of energy intake data using fundamental principles of energy physiology: 1. Derivation of cut-off limits to identify under-recording. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 45, 569–581. [Google Scholar]

- Joosen, A.M.; Westerterp, K.R. Energy expenditure during overfeeding. Nutr. Metab. 2006, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P. Biology or behavior: Which is the strongest contributor to weight gain? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2013, 2, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G.A.; Frühbeck, G.; Ryan, D.H.; Wilding, J.P. Management of obesity. Lancet 2016, 387, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell, J.; Gibbons, C.; Caudwell, P.; Finlayson, G.; Hopkins, M. Appetite control and energy balance: Impact of exercise. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, S.F.; Tucker, J.A.; Hazell, T.J. Exercise-induced appetite suppression: An update on potential mechanisms. Physiol. Rep. 2024, 12, e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, J.E.; Warthon-Medina, M.; Albar, S.; Alwan, N.A.; Ness, A.; Roe, M.; Wark, P.A.; Greathead, K.; Burley, V.J.; Finglas, P.; et al. DIET@NET: Best Practice Guidelines for dietary assessment in health research. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Dodd, K.W.; Kipnis, V.; Thompson, F.E.; Potischman, N.; Schoeller, D.A.; Baer, D.J.; Midthune, D.; Troiano, R.P.; Bowles, H.; et al. Comparison of self-reported dietary intakes from the Automated Self-Administered 24-h recall, 4-d food records, and food-frequency questionnaires against recovery biomarkers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, M.F.; Chaput, J.-P.; Ritz, C.; Dalskov, S.-M.; Andersen, R.; Astrup, A.; Tetens, I.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Sjödin, A. Fatness predicts decreased physical activity and increased sedentary time, but not vice versa: Support from a longitudinal study in 8- to 11-year-old children. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutin, B. Diet vs. exercise for the prevention of pediatric obesity: The role of exercise. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Study Inclusion Criteria | Study Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Adiposity | Validated methods including dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), hydrostatic weighing, air displacement plethysmography (ADP), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and skinfold estimation of percent body fat. | Non-validated or indirect proxy measures of adiposity (e.g., BMI, waist circumference). |

| Energy Intake (EI) | Validated dietary assessment methods common to community-based studies, including 24 h dietary recall, food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), food diary/records, digital dietary assessment tools, and diet history interviews. | Absence of clear methodology, unvalidated self-reports. |

| Physical Activity (PA) | Validated methods included accelerometers, pedometers, heart rate monitors, and GPS devices. | Non-validated measures, e.g., unstructured self-report diaries and questionnaires. |

| Statistical treatment | Statistical regression models with adiposity as the response variable and PA and EI as explanatory variables, adjusting in turn for the covariates. | Simple correlations between adiposity and EI, and/or adiposity and PA. |

| Study | Participants | Measurements | Analyses | Some Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOOK Pre-adolescence Study | 534 (278 boys), mainly White, age 8 and 12 years, outer suburban mid-sized Australian city. | Pedometers, accelerometers; percent body fat (%BF) DEXA; 1-day dietary record at age 8 y, 2-day recall at 12 y). | General linear mixed method model, with adjustment for relevant covariates. | %BF independently and negatively associated with PA (p < 0.001); no association between %BF and EI (p = 0.3; no evidence of any effect of under-reporting in children with higher %BF. |

| Helena/European Youth Heart Study | 1721 adolescents (792 boys): presumed mainly White from 10 cities in 9 European countries. | Accelerometry; skinfolds, ADP, DEXA, BIA; EI; 24 h dietary recall. | Multilevel analysis with adjustments for relevant covariates. | Fat mass was negatively associated with energy intake in both studies (≤0.006); More active adolescents were leaner with greater EI than less active adolescents, who had greater %BF; no evidence of any effect of under-reporting in children with higher %BF. |

| Iowa Bone Development Study | 493 participants (243 boys), mainly White, were assessed at least 3 times from ages 5 to 19 years. USA. | PA: Accelerometry; adiposity: DEXA; EI: food frequency questionnaires. | Quartile ranking for EI; logistic regression models with adjustment for relevant covariates. | Declining PA was associated with increased odds of obesity (2.77; 95% CI, 1.16, 6.58); little or no association between EI and adiposity; with higher EI tending to lower obesity odds (95% CI 0.74, (0.39, 1.40) |

| LOOK Adolescence Study | 556 participants (289 male) at age 12; 269 remeasured at age 16, from an outer suburban mid-sized Australian city. | Adiposity: DEXA; PA: accelerometry; EI: 2 × 24 h recall, weekday/weekend multi-pass methodology. | General linear mixed modeling with adjustments for relevant covariates. | %BF was independently negatively related to PA (p < 0.001); no relationship between %BF and energy intake (p = 0.4). Adjustments for any potential under-reporting in individuals with higher %BF; no evidence of under-reporting in children with higher %BF. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Telford, R.D.; Jayasinghe, S.; Byrne, N.M.; Telford, R.M.; Hills, A.P. Do Physical Activity and Diet Independently Account for Variation in Body Fat in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review Unpacking the Roles of Exercise and Diet in Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3779. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233779

Telford RD, Jayasinghe S, Byrne NM, Telford RM, Hills AP. Do Physical Activity and Diet Independently Account for Variation in Body Fat in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review Unpacking the Roles of Exercise and Diet in Childhood Obesity. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3779. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233779

Chicago/Turabian StyleTelford, Richard D., Sisitha Jayasinghe, Nuala M. Byrne, Rohan M. Telford, and Andrew P. Hills. 2025. "Do Physical Activity and Diet Independently Account for Variation in Body Fat in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review Unpacking the Roles of Exercise and Diet in Childhood Obesity" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3779. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233779

APA StyleTelford, R. D., Jayasinghe, S., Byrne, N. M., Telford, R. M., & Hills, A. P. (2025). Do Physical Activity and Diet Independently Account for Variation in Body Fat in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review Unpacking the Roles of Exercise and Diet in Childhood Obesity. Nutrients, 17(23), 3779. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233779