Impact of Mango Bagasse and Peel Confectionery Rich in Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota, Metabolite Profiles, and Genetic Regulation in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Wistar Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Confectionery Procurement

2.2. Animal Treatment

2.2.1. Experimental Design and Diet

2.2.2. Treatment

2.2.3. Measurement of Feed Intake, Body Composition, and Sample Collection

2.3. Gut Microbiota and SCFA Analyses

2.3.1. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.3.2. Library Preparation and 16S Sequencing

Quality and Preprocessing Analysis

2.3.3. Quantification of SCFAs

2.4. Gene Expression

2.4.1. RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

2.4.2. Quality and Preprocessing Analysis

2.4.3. Differential Expression and Enrichment Analysis

2.4.4. qPCR Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

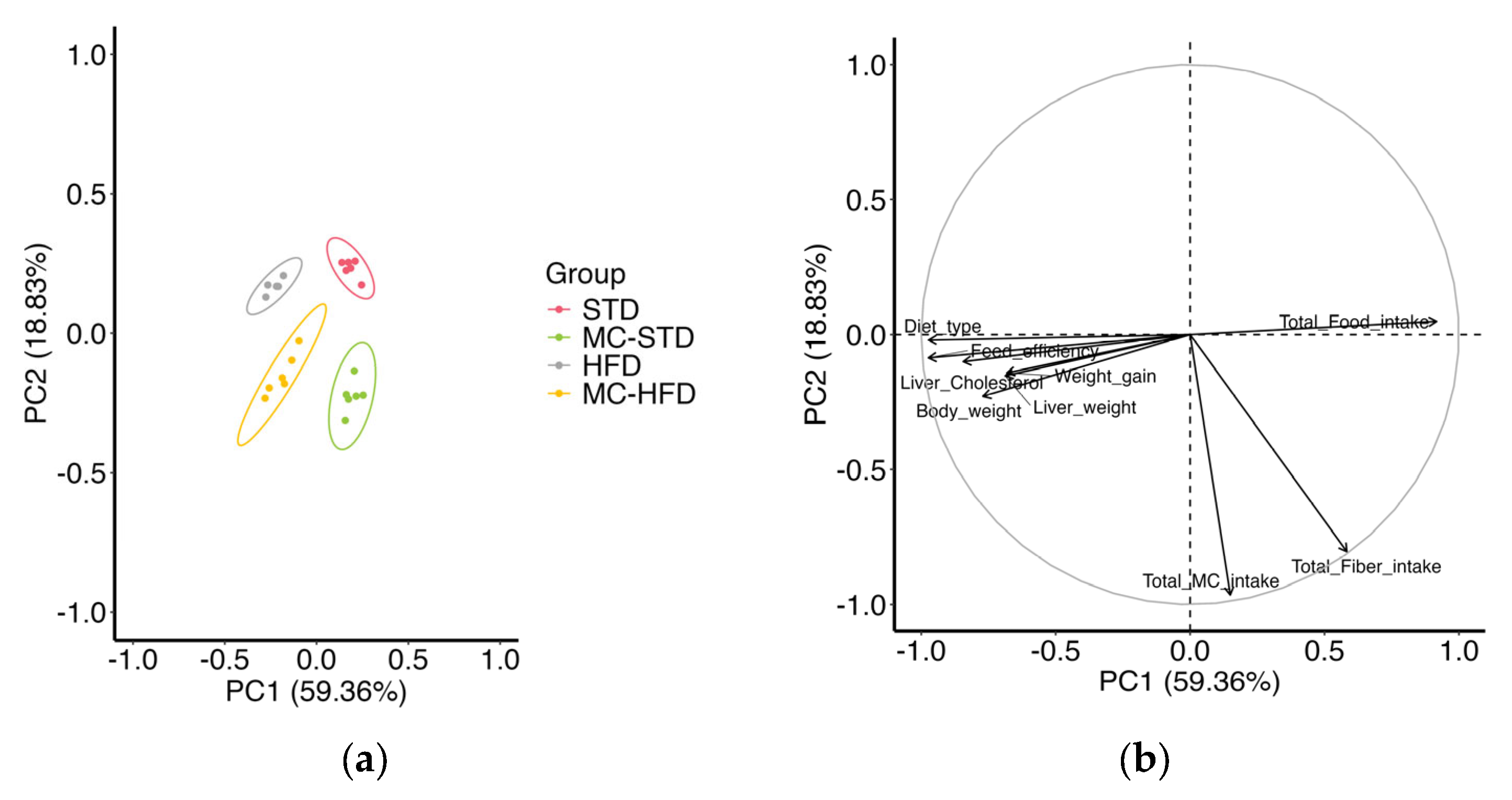

3.1. Animal Growth

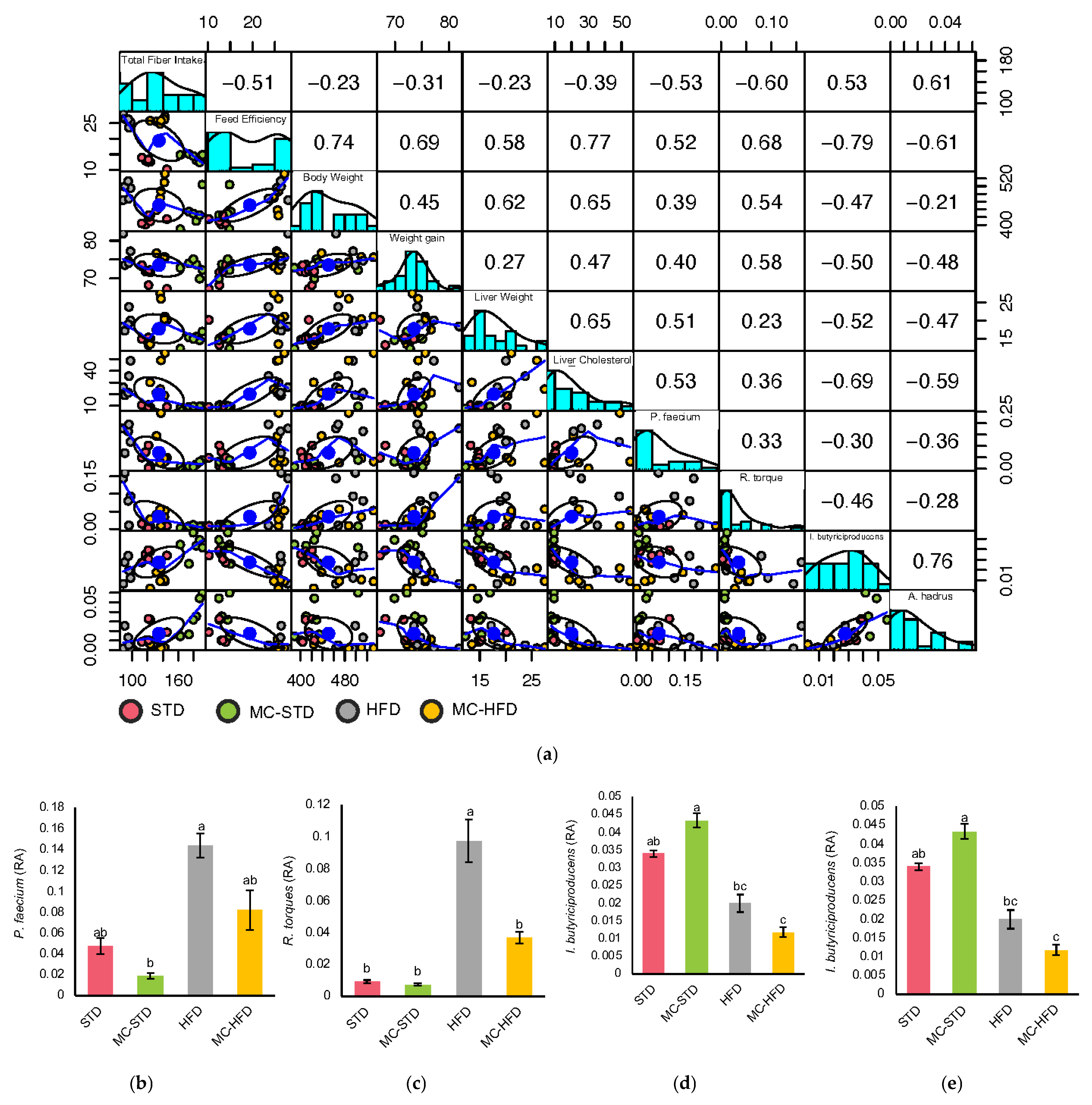

3.2. Gut Microbiota and SCFAs

3.2.1. Gut Microbiota Diversity and Taxonomic Composition

3.2.2. Gut Microbiota Correlations with Fiber Intake and Body Composition

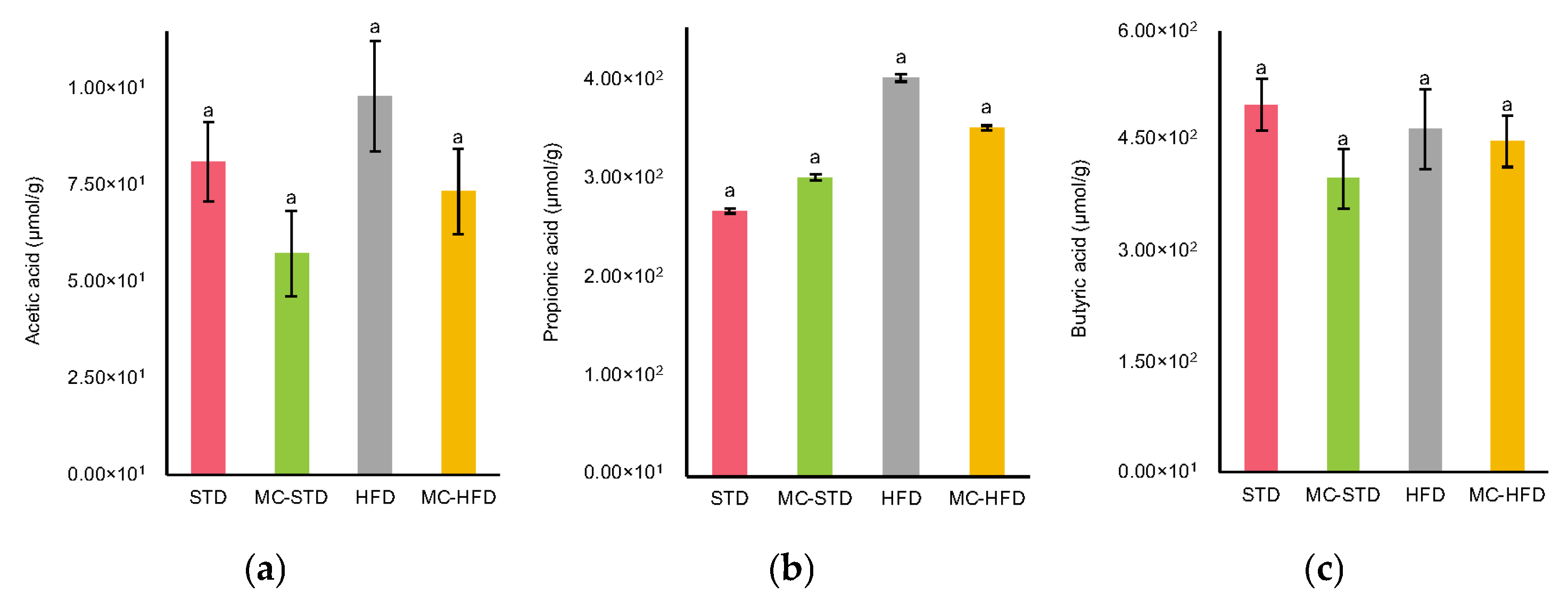

3.2.3. SCFAs Concentrations

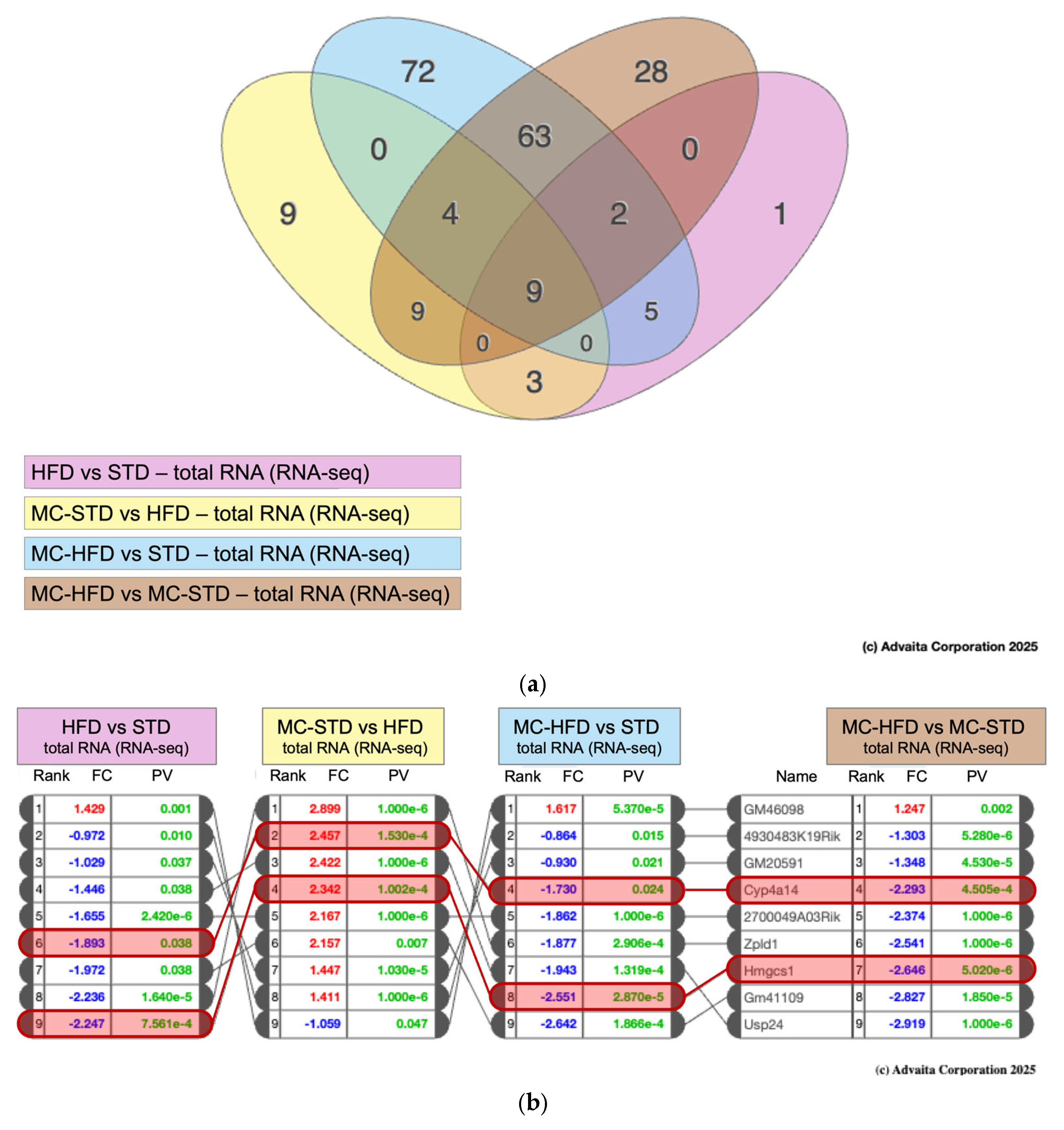

3.3. Gene Expression

3.3.1. Transcriptomic Overview

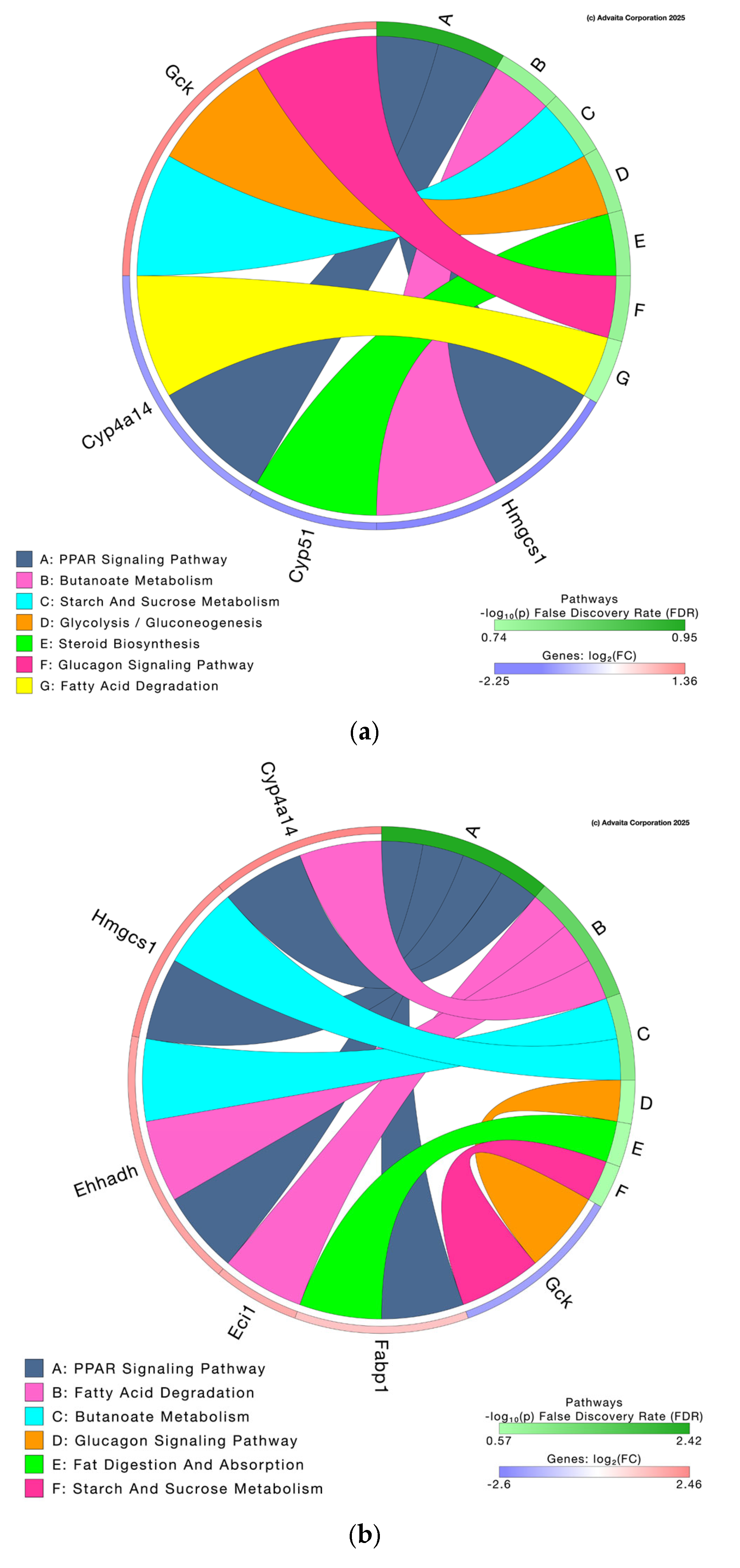

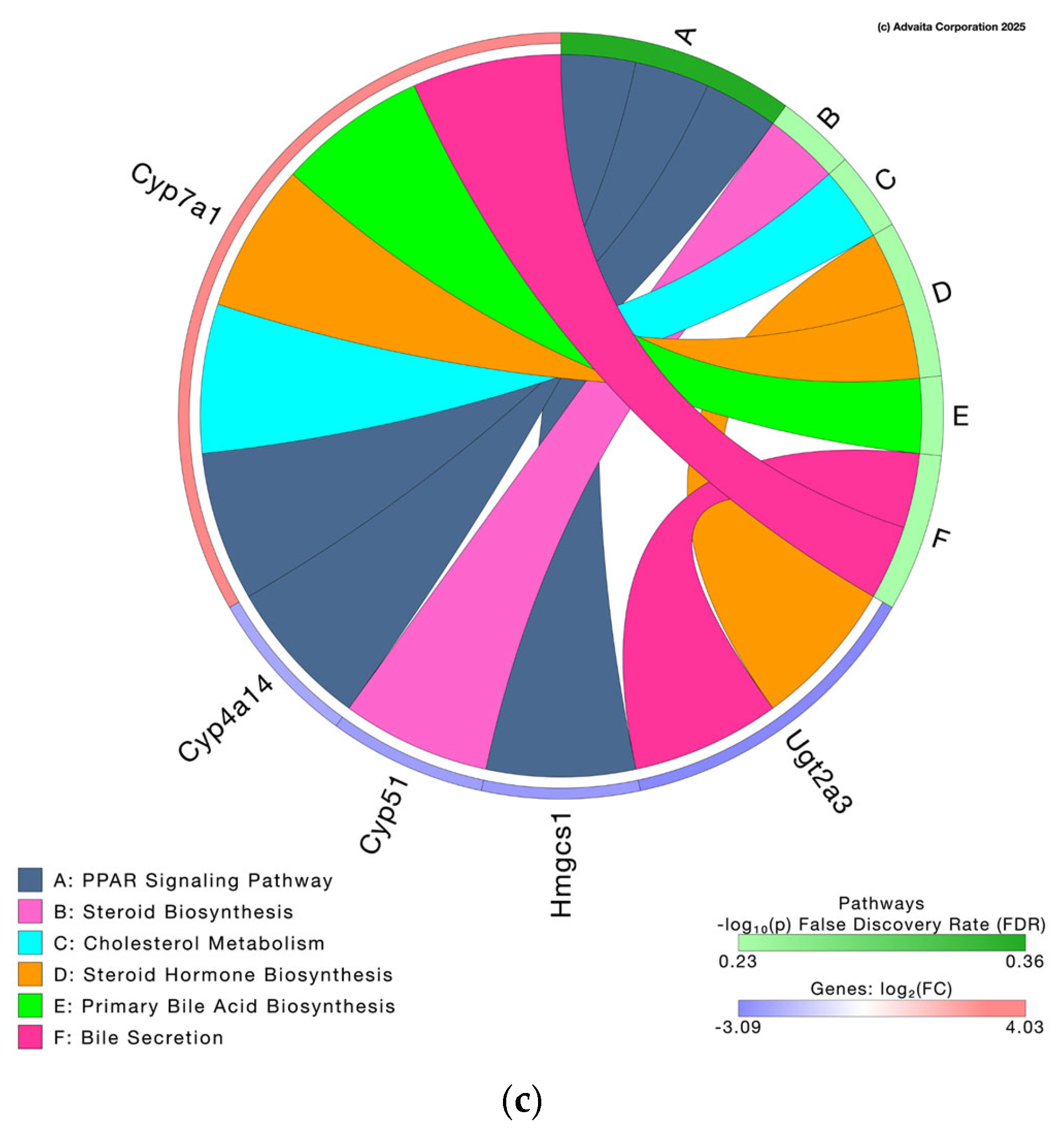

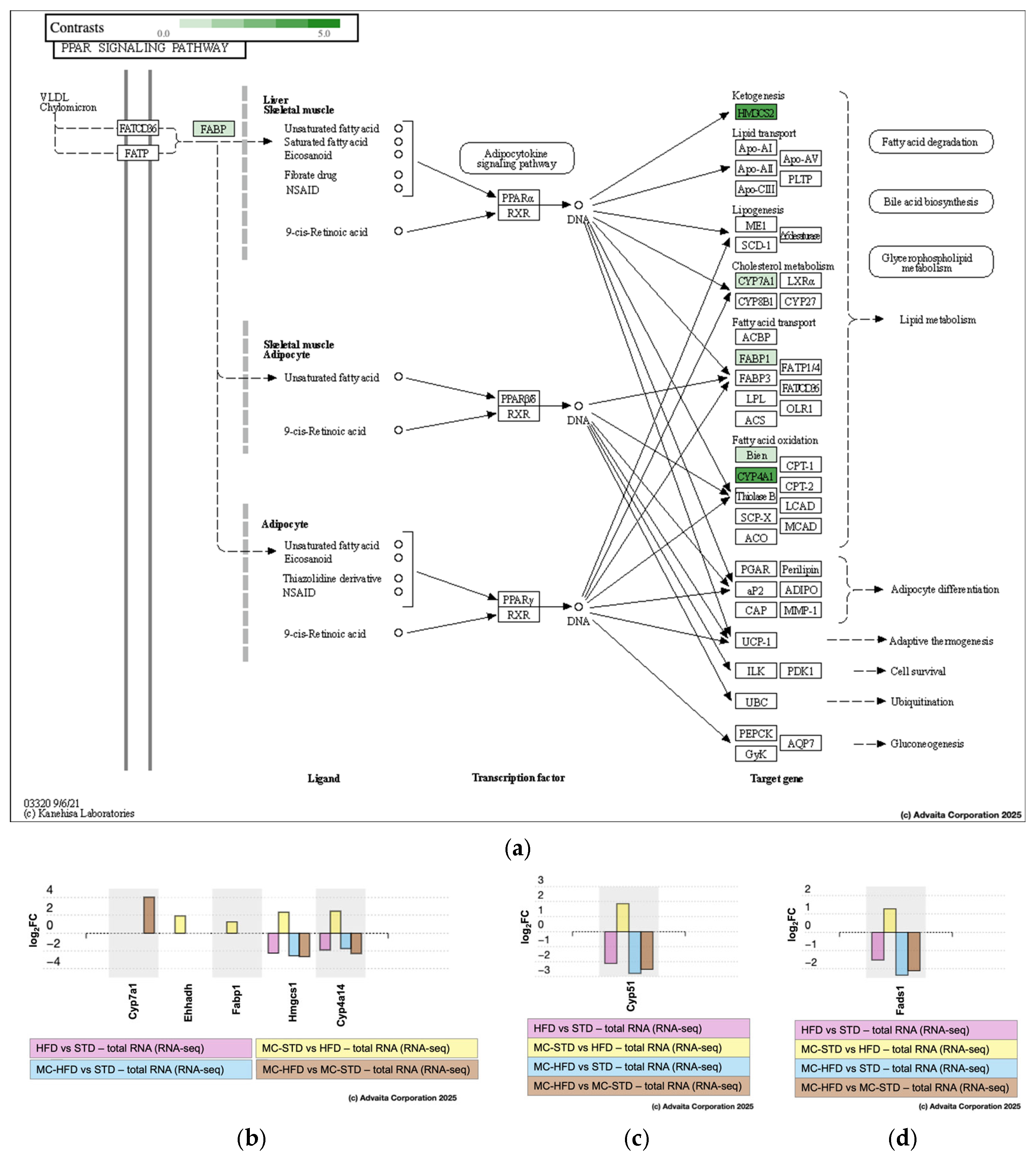

3.3.2. Pathway Analysis and Differential Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Collaboration |

| Cyp4a14 | Cytochrome P450 family 4 subfamily A polypeptide 14 |

| Cyp51 | Cytochrome P450 family 51 |

| Cyp7a1 | Cytochrome P450 family 7 subfamily A member 1 |

| Eci1 | Enoyl-CoA delta isomerase 1 |

| Ehhadh | Enoyl-CoA hydratase and 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

| Fabp1 | Fatty acid binding protein 1 |

| Fads1 | Fatty acid desaturase 1 |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| HFD | High-fat diet |

| Hmgcs1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 1 |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| MAFLD | metabolic associated fatty liver disease |

| MC | Mango bagasse and peel confectionery |

| MC-HFD | High-fat diet supplemented with mango bagasse and peel confectionery |

| MC-STD | Standard diet supplemented with mango bagasse and peel confectionery |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| RAs | Relative abundances |

| SCFAs | Short-chain fatty acids |

| UAQ | Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro |

| Ugt2a3 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase family 2 member A3 |

References

- Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.B.; Ziani, K.; Mititelu, M.; Oprea, E.; Neacșu, S.M.; Moroșan, E.; Dumitrescu, D.E.; Roșca, A.C.; Drăgănescu, D.; Negrei, C. Therapeutic Benefits and Dietary Restrictions of Fiber Intake: A State of the Art Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, E.J.; Meyer, R.K.; Weninger, S.N.; Martinez, T.; Wachsmuth, H.R.; Pignitter, M.; Auñon-Lopez, A.; Kangath, A.; Duszka, K.; Gu, H.; et al. Impact of Plant-Based Dietary Fibers on Metabolic Homeostasis in High-Fat Diet Mice via Alterations in the Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 2014–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqsood, S.; Arshad, M.T.; Ikram, A.; Gnedeka, K.T. Fruit-Based Diet and Gut Health: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Fan, G.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. The Regulatory Roles of Dietary Fibers on Host Health via Gut Microbiota-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022, 62, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiezia, C.; Di Rosa, C.; Fintini, D.; Ferrara, P.; De Gara, L.; Khazrai, Y.M. Nutritional Approaches in Children with Overweight or Obesity and Hepatic Steatosis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.S.; den Hartigh, L.J. Gut Microbial-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids: Impact on Adipose Tissue Physiology. Nutrients 2023, 15, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Dai, X. Potato Resistant Starch Inhibits Diet-Induced Obesity by Modifying the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Obese Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 180, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, Y.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; de los Ríos-Arellano, E.A.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Hinojosa-Alvarez, S.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K. Mango By-Product-Based High-Fiber Confectionery Attenuates Liver Steatosis and Alters Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lange, O.; Proczko-Stepaniak, M.; Mika, A. Short-Chain Fatty Acids—A Product of the Microbiome and Its Participation in Two-Way Communication on the Microbiome-Host Mammal Line. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2023, 12, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga-Garrido, S.M.; Hong, Q.; Cross, T.W.L.; Hutchison, E.R.; Han, J.; Thomas, S.P.; Vivas, E.I.; Denu, J.; Ceschin, D.G.; Tang, Z.Z.; et al. Gut Microbiome Variation Modulates the Effects of Dietary Fiber on Host Metabolism. Microbiome 2021, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, F.; He, H.; Johnston, L.J.; Dai, X.; Wu, C.; Ma, X. Dietary Fiber-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids: A Potential Therapeutic Target to Alleviate Obesity-Related Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waddell, I.S.; Orfila, C. Dietary Fiber in the Prevention of Obesity and Obesity-Related Chronic Diseases: From Epidemiological Evidence to Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 8752–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuncion, P.; Liu, C.; Castro, R.; Yon, V.; Rosas, M., Jr.; Hooshmand, S.; Kern, M.; Young Hong, M. The Effects of Fresh Mango Consumption on Gut Health and Microbiome-Randomized Controlled Trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2069–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G.; Morales-Ruan, C.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Méndez-Gómez-Humarán, I.; Ávila-Arcos, M.A.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Ávila-Curiel, A.; et al. Sobrepeso y Obesidad En Población Escolar y Adolescente. Salud Publica Mex. 2024, 66, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Franquesa, A.; Montemurro, M.; Casertano, M.; Fogliano, V. The Food By-Products Bioprocess Wheel: A Guidance Tool for the Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 152, 104652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cazares, L.A.; Hernández-Navarro, F.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Campos-Vega, R.; Reyes-Vega, M.D.L.L.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Morales-Sánchez, E.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Gaytán-Martínez, M. Mango-Bagasse Functional-Confectionery: Vehicle for Enhancing Bioaccessibility and Permeability of Phenolic Compounds. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 3906–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzardo-Ocampo, I.; Flores-Zavala, D.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Olivas-Aguirre, F.J.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Gaytán-Martínez, M. Sensory Evaluation and in Vitro Prebiotic Effect of (Poly)Phenols and Dietary Fiber-Rich Mango Bagasse-Enriched Confections. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 142149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Cazares, L.A.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Wall-Medrano, A.; Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Reyes-Vega, M.L.; Vázquez-Landaverde, P.A.; Gaytán-Martínez, M. Untargeted Metabolomic Evaluation of Mango Bagasse and Mango Bagasse Based Confection under in Vitro Simulated Colonic Fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 54, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Method of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999; Especificaciones Técnicas para la Producción, Cuidado y Uso de los Animales de Laboratorio. Diario Oficial de la Federación: Mexico City, México, 1999.

- Sagkan-Ozturk, A.; Arpaci, A. The Comparison of Changes in Fecal and Mucosal Microbiome in Metabolic Endotoxemia Induced by a High-Fat Diet. Anaerobe 2022, 77, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etxeberria, U.; Hijona, E.; Aguirre, L.; Milagro, F.I.; Bujanda, L.; Rimando, A.M.; Martínez, J.A.; Portillo, M.P. Pterostilbene-Induced Changes in Gut Microbiota Composition in Relation to Obesity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1500906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Chen, H.; Cao, M.; Li, W.; Luo, H.; Wu, Z. Huang-Qi San Improves Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Exerts Protective Effects against Hepatic Steatosis in High Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 126, 109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Keirsey, K.I.; Kirkland, R.; Grunewald, Z.I.; Fischer, J.G.; de La Serre, C.B. Blueberry Supplementation Influences the Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Insulin Resistance in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Rats. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, I.; Ortiz, A.; Sanchez-Pardo, M.; Garduño-Siciliano, L.; Hernández-Ortega, M.; Villarreal, F.; Meaney, E.; Najera, N.; Ceballos, G.M. Obesity and Cardiovascular Risk Improvement Using Cacao By-Products in a Diet-Induced Obesity Murine Model. J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Carbohydrate Intake for Adults and Children: WHO Guideline; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 100p.

- López-Olmedo, N.; Carriquiry, A.L.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Ramírez-Silva, I.; Espinosa-Montero, J.; Hernández-Barrera, L.; Campirano, F.; Martínez-Tapia, B.; Rivera, J.A. Usual Intake of Added Sugars and Saturated Fats Is High While Dietary Fiber Is Low in the Mexican Population. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1856S–1865S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane, G.H. a simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Henry, M.; Stevens, H.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/index.html (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- Figueroa, L.M.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K.; Senés-Guerrero, C.; Santacruz, A.; Pacheco, A.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A. Assessment of the Bacterial Diversity of Agave Sap Concentrate, Resistance to in Vitro Gastrointestinal Conditions and Short-Chain Fatty Acids Production. Food Res. Int. 2021, 140, 109862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High-Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. Sequence Analysis STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar-Rojas, P.; Alvarado, J.C.; Fuentes-Santamaría, V.; Cruz Gabaldón-Ull, M.; Juiz, J.M. Validation of Reference Genes for RT-QPCR Analysis in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss: A Study in Wistar Rat. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing Real-Time PCR Data by the Comparative Ct Methos. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura-calixto, F. Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Product: A New Concept and a Potential Food Ingredient. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 4303–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, T.; Liang, X.; Zhu, L.; Fang, Y.; Dong, L.; Zheng, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Cai, T.; et al. A Decrease in Flavonifractor Plautii and Its Product, Phytosphingosine, Predisposes Individuals with Phlegm-Dampness Constitution to Metabolic Disorders. Cell Discov. 2025, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Cani, P.D. Diabetes, Obesity and Gut Microbiota. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013, 27, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohesara, S.; Mostafavi Abdolmaleky, H.; Pirani, A.; Pettinato, G.; Thiagalingam, S. The Obesity–Epigenetics–Microbiome Axis: Strategies for Therapeutic Intervention. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.-N.; Liu, X.-T.; Liang, Z.-H.; Wang, J.-H. Gut Microbiota in Obesity. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 3837–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, N.; Hou, C.; Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Bioactivity and Probiotic Potential of Bound Polyphenols in Insoluble and Soluble Dietary Fibers from Mango Peel during in Vitro Digestion and Fecal Fermentation. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shallangwa, S.M.; Ross, A.W.; Morgan, P.J. Single, but Not Mixed Dietary Fibers Suppress Body Weight Gain and Adiposity in High Fat-Fed Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1544433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Peng, Y. Phascolarctobacterium Faecium Abundant Colonization in Human Gastrointestinal Tract. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Yuan, J.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Yin, K.; Wang, F.; Li, D. Overweight and Underweight Status Are Linked to Specific Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Intermediates. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3189–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, K.; Liang, L.; Yang, Y.; Lu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, T.; Fan, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Multi-Omics Analyses of the Gut Microbiota and Metabolites in Children with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. mSystems 2025, 10, e01148-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Qin, Q.; Chen, J.; Yan, S.; Li, T.; Gao, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, A.; Ding, S. Gut Microbiome Alterations in Patients with Visceral Obesity Based on Quantitative Computed Tomography. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 11, 823262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, G.; Long, W.; Xue, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Pang, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Accelerated Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota during Aggravation of DSS-Induced Colitis by a Butyrate-Producing Bacterium. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kläring, K.; Hanske, L.; Bui, N.; Charrier, C.; Blaut, M.; Haller, D.; Plugge, C.M.; Clavel, T. Intestinimonas Butyriciproducens Gen. Nov., Sp. Nov., a Butyrate-Producing Bacterium from the Mouse Intestine. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4606–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Ramesh, G.; Wu, M.; Jensen, E.T.; Crago, O.; Bertoni, A.G.; Gao, C.; Hoffman, K.L.; Sheridan, P.A.; Wong, K.E.; et al. Butyrate-Producing Bacteria and Insulin Homeostasis: The Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study (MILES). Diabetes 2022, 71, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnina, I.; Gudra, D.; Silamikelis, I.; Viksne, K.; Roga, A.; Skinderskis, E.; Fridmanis, D.; Klovins, J. Variations in the Relative Abundance of Gut Bacteria Correlate with Lipid Profiles in Healthy Adults. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.Y.P.; Visvalingam, V.; Wahli, W. The PPAR–Microbiota–Metabolic Organ Trilogy to Fine-tune Physiology. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 9706–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary Fibre in Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, D.P.; De La Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 424615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinelli, V.; Biscotti, P.; Martini, D.; Del Bo’, C.; Marino, M.; Meroño, T.; Nikoloudaki, O.; Calabrese, F.M.; Turroni, S.; Taverniti, V.; et al. Effects of Dietary Fibers on Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Gut Microbiota Composition in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Besten, G.; Bleeker, A.; Gerding, A.; van Eunen, K.; Havinga, R.; van Dijk, T.H.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Jonker, J.W.; Groen, A.K.; Reijngoud, D.-J.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Protect Against High-Fat Diet–Induced Obesity via a PPARg-Dependent Switch From Lipogenesis to Fat Oxidation. Diabetes 2015, 64, 2398–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grygiel-Górniak, B. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors and Their Ligands: Nutritional and Clinical Implications—A Review. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Su, W.; Ruan, X.; Wang, B.; Zheng, F.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.-Å.; Guan, Y. Ablation of Cytochrome P450 Omega-Hydroxylase 4A14 Gene Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3181–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, A.; Gruben, N.; Catrysse, L.; Koehorst, M.; Koster, M.; Kloosterhuis, N.J.; Gerding, A.; Havinga, R.; Bloks, V.W.; Bongiovanni, L.; et al. The Hepatocyte IKK:NF-ΚB Axis Promotes Liver Steatosis by Stimulating de Novo Lipogenesis and Cholesterol Synthesis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 54, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xiao, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, F. HUB Genes Transcriptionally Regulate Lipid Metabolism in Alveolar Type II Cells under LPS Stimulation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromovsky, A.D.; Schugar, R.C.; Brown, A.L.; Helsley, R.N.; Burrows, A.C.; Ferguson, D.; Zhang, R.; Sansbury, B.E.; Lee, R.G.; Morton, R.E.; et al. Δ-5 Fatty Acid Desaturase FADS1 Impacts Metabolic Disease by Balancing Proinflammatory and Proresolving Lipid Mediators. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OmicsBox—Bioinformatics Made Easy. BioBam Bioinformatics (Version 2.0.36). 3 March 2019. Available online: www.biobam.com/omicsbox (accessed on 26 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbosa, Y.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Magallón-Gayón, E.; Hinojosa-Alvarez, S.; Chico-Peralta, A.; de Donato, M.; Ramírez-Jiménez, A.K. Impact of Mango Bagasse and Peel Confectionery Rich in Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota, Metabolite Profiles, and Genetic Regulation in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Wistar Rats. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233780

Barbosa Y, Gaytán-Martínez M, Chavez-Santoscoy RA, Magallón-Gayón E, Hinojosa-Alvarez S, Chico-Peralta A, de Donato M, Ramírez-Jiménez AK. Impact of Mango Bagasse and Peel Confectionery Rich in Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota, Metabolite Profiles, and Genetic Regulation in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Wistar Rats. Nutrients. 2025; 17(23):3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233780

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbosa, Yuritzi, Marcela Gaytán-Martínez, Rocio Alejandra Chavez-Santoscoy, Erika Magallón-Gayón, Silvia Hinojosa-Alvarez, Adriana Chico-Peralta, Marcos de Donato, and Aurea K. Ramírez-Jiménez. 2025. "Impact of Mango Bagasse and Peel Confectionery Rich in Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota, Metabolite Profiles, and Genetic Regulation in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Wistar Rats" Nutrients 17, no. 23: 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233780

APA StyleBarbosa, Y., Gaytán-Martínez, M., Chavez-Santoscoy, R. A., Magallón-Gayón, E., Hinojosa-Alvarez, S., Chico-Peralta, A., de Donato, M., & Ramírez-Jiménez, A. K. (2025). Impact of Mango Bagasse and Peel Confectionery Rich in Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota, Metabolite Profiles, and Genetic Regulation in High-Fat-Diet-Fed Wistar Rats. Nutrients, 17(23), 3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17233780