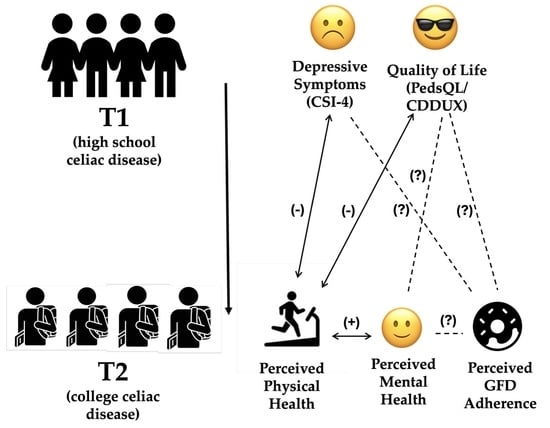

A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Mental Health and Quality of Life as Predictors of College Physical Health, Mental Health, and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Associations at T2

3.2. Prospective T1 to T2 Associations

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CeD | Celiac Disease |

| GFD | Gluten-free Diet |

| CSI-4 | Child Symptom Inventory-4 Major Depressive Disorder subscale |

| CDDUX | Celiac Disease DUX questionnaire |

| PedsQL | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory |

| TTG IgA | Tissue Transglutaminase Immunoglobulin A |

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Child and Adolescent Mental Health; 2022 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.; Reda, S.; Martin, S.; Long, P.; Franklin, A.; Bedoya, S.Z.; Wiener, L.; Wolters, P.L. The Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Chronic Illness: Results of a Quality Improvement Survey. Children 2022, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.; Crapnell, T.; Lau, L.; Bennett, A.; Lotstein, D.; Ferris, M.; Kuo, A. Emerging Adulthood as a Critical Stage in the Life Course; Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 123–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jericho, H.; Khan, N.; Cordova, J.; Sansotta, N.; Guandalini, S.; Keenan, K. Call for Action: High Rates of Depression in the Pediatric Celiac Disease Population Impacts Quality of Life. JPGN Rep. 2021, 2, e074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, H.J. Adult Celiac Disease and Its Malignant Complications. Gut Liver 2009, 3, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadow, K.; Sprafkin, J. Child Symptom Inventories Manual; Checkmate Plus: Stony Brook, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn, R.K.; Winkler, L.M.F.; Zwinderman, K.H.; Mearin, M.L.; Koopman, H.M. CDDUX: A disease-specific health-related quality-of-life questionnaire for children with celiac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 47, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Rode, C.A. The PedsQL™: Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory. Med. Care 1999, 37, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrady, M.E.; Hommel, K.A. Medication Adherence and Health Care Utilization in Pediatric Chronic Illness: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgcomb, J.B.; Zima, B. Medication Adherence Among Children and Adolescents with Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarar, Z.I.; Zafar, M.U.; Farooq, U.; Basar, O.; Tahan, V.; Daglilar, E. The Progression of Celiac Disease, Diagnostic Modalities, and Treatment Options. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2021, 9, 23247096211053702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.S.; Kirsch, A.C.; Dickson, D.A.; Bryant, F.B. Negotiating the Transition to College: Developmental Trajectories and Gender Differences in Psychological Functioning, Cognitive-Affective Strategies, and Social Well-Being. Emerg. Adulthood 2014, 2, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time Period | Score | Mean (SD) | Correlation with T2 Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health | Mental Health | GFD Adherence | |||

| T1 | CDDUX | 31.05 (±4.48) | τ = 0.17, FDR = 0.13 | τ = 0.19, FDR = 0.13 | τ = 0.22, FDR = 0.13 |

| CSI-4 | 14.28 (±4.31) | τ = −0.31, FDR = 0.02 | τ = −0.18, FDR = 0.20 | τ = −0.13, FDR = 0.28 | |

| PedsQL | 40.81 (±13.38) | τ = −0.28, FDR = 0.04 | τ = −0.23, FDR = 0.06 | τ = 0.03, FDR = 0.78 | |

| T2 | Physical Health Perception | 14.72 (±3.57) | -- | τ = 0.41, FDR = 0.001 | τ = 0.03, FDR = 0.78 |

| Mental Health Perception | 6.49 (±2.26) | τ = 0.41, FDR = 0.001 | -- | τ = −0.08, FDR = 0.77 | |

| GFD Adherence | 11.69 (±2.52) | τ = 0.03, FDR = 0.78 | τ = −0.08, FDR = 0.77 | -- | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosher, T.L.; Su, L.J.; López-Rivera, J.A.; Verma, R.; Keenan, K.; Jericho, H. A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Mental Health and Quality of Life as Predictors of College Physical Health, Mental Health, and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223568

Mosher TL, Su LJ, López-Rivera JA, Verma R, Keenan K, Jericho H. A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Mental Health and Quality of Life as Predictors of College Physical Health, Mental Health, and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223568

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosher, Tierra L., Lilly Jill Su, Javier A. López-Rivera, Ritu Verma, Kate Keenan, and Hilary Jericho. 2025. "A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Mental Health and Quality of Life as Predictors of College Physical Health, Mental Health, and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223568

APA StyleMosher, T. L., Su, L. J., López-Rivera, J. A., Verma, R., Keenan, K., & Jericho, H. (2025). A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Mental Health and Quality of Life as Predictors of College Physical Health, Mental Health, and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in Celiac Disease. Nutrients, 17(22), 3568. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223568