Adherence to Mediterranean Healthy Lifestyle Patterns and Potential Barriers: A Comparative Study of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, and Social Participation Between German and Turkish Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Promotion and Development of Surveys

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Data Privacy

2.4. Survey Questionnaires

2.4.1. MedLife Index

2.4.2. International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF)

2.4.3. Short Social Participation Questionnaire (SSPQ-L)

2.4.4. The MedDiet Barriers Questionnaire (MBQ)

2.4.5. Additional Questions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Responders

3.2. Medlife Index

3.2.1. Block 1: Mediterranean Food Consumption Patterns

3.2.2. Block 2: Mediterranean Dietary Habits

3.2.3. Block 3: Physical Activity, Rest, Social Habits, and Conviviality

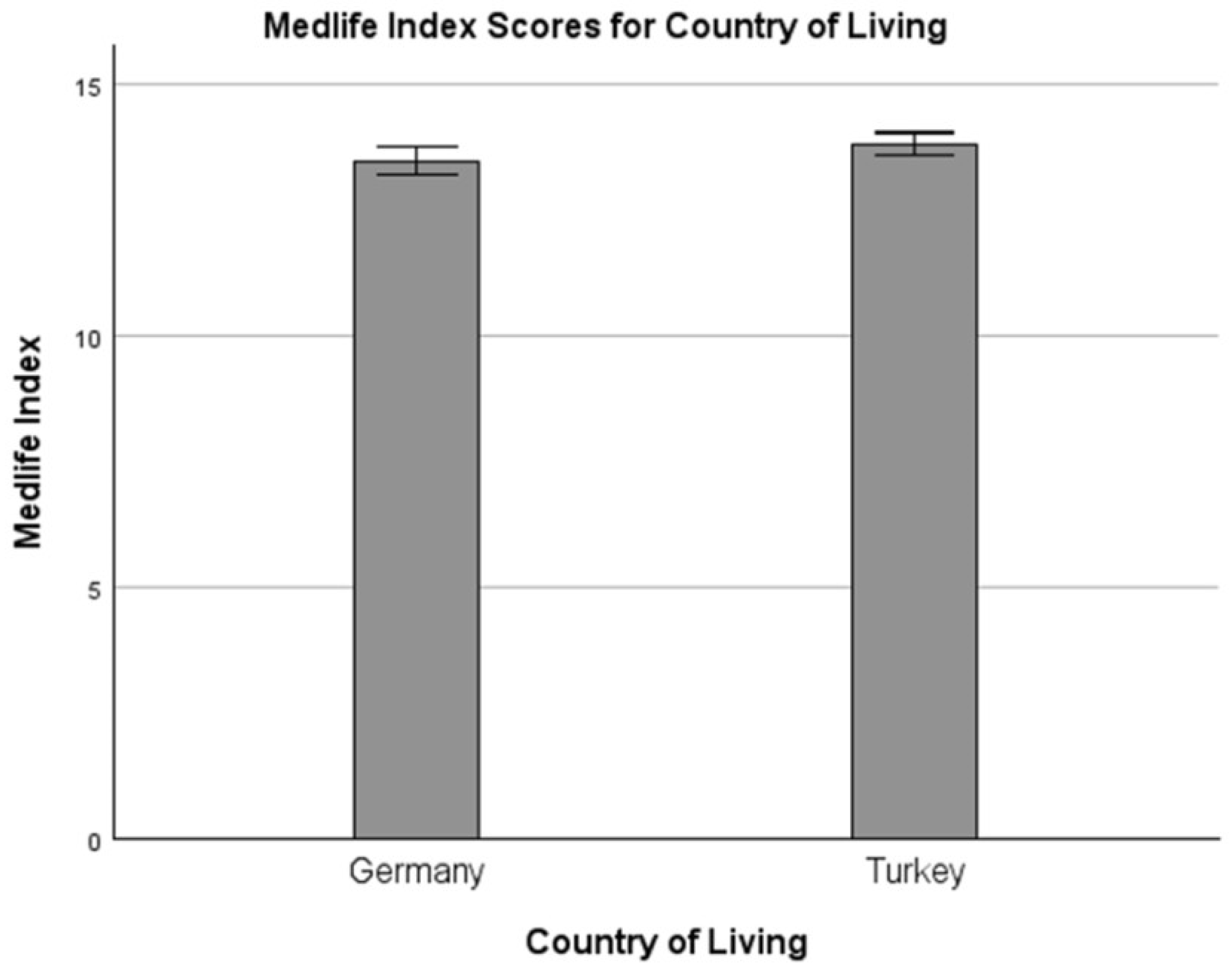

3.2.4. MedLife Index’s Total Score and Category Classifications

3.3. MedDiet Awareness and MedDiet Barriers Questionnaire (MBQ) Scores

3.4. Physical Activity and Social Participation

3.5. Correlation Between Total Scores of MedLife Index, IPAQ-SF, and SSPQ-L

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic and Socioeconomic Differences

4.2. Adherence to the MedDiet and Eating Habits

4.3. Physical Activity, Social Participation, and Their Association with MedLife Adherence

4.4. MedDiet Awareness and Perceived Barriers

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Practical Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang de Pinho, I.; Giorelli, G.; Oliveira Toledo, D. A narrative review examining the relationship between mental health, physical activity, and nutrition. Discov. Psychol. 2024, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorca-Camara, V.; Bosque-Prous, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; O’Callaghan-Gordo, C.; Bach-Faig, A. Environmental and health sustainability of the Mediterranean diet: A systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Del Rio, D.; Drescher, G.; Estruch, R.; Hanson, C.; Harlan, T.; Hu, F.B.; Loi, M.; McClung, J.P.; Mojica, A.; et al. MED diet: Promotion and dissemination of healthy eating. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Scazzina, F.; Paternò Castello, C.; Giampieri, F.; Quiles, J.L.; Briones Urbano, M.; Battino, M.; Galvano, F.; Iacoviello, L.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Underrated aspects of a true Mediterranean diet: Understanding traditional features for worldwide application of a “Planeterranean” diet. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolomeo, M.; De Carli, L.; Guidi, S.; Zanardi, M.; Giacomini, D.; Devecchi, C.; Pistone, E.; Ponta, M.; Simonetti, P.; Sykes, K.; et al. The Mediterranean Diet: From the pyramid to the circular model. Med. J. Nutr. Met. 2023, 16, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A. A transnational movement to support the sustainable transition towards a healthy and eco-friendly agri-food system through the promotion of MEDIET and its lifestyle in modern society: MEDIET4ALL. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34 (Suppl. 3), ckae144.643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Faig, A.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Reguant, J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Dernini, S.; Medina, F.X.; Battino, M.; Belahsen, R.; Miranda, G.; et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid today: Science and cultural updates. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2274–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujelbane, M.A.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Kerkeni, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Bouaziz, B.; Masmoudi, L.; Heydenreich, J.; Schallhorn, C.; Müller, G.; et al. Regional variations in Mediterranean diet adherence: A sociodemographic and lifestyle analysis across Mediterranean and non-Mediterranean regions within the MEDIET4ALL project. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1596681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujelbane, M.A.; Ammar, A.; Salem, A.; Kerkeni, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Bouaziz, B.; Masmoudi, L.; Heydenreich, J.; Schallhorn, C.; Müller, G.; et al. Gender-specific insights into adherence to Mediterranean diet and lifestyle: Analysis of 4 000 responses from the MEDIET4ALL project. Front. Nutr. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.; Boujelbane, M.A.; Salem, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Bouaziz, B.; Kerkeni, M.; Masmoudi, L.; Heydenreich, J.; Schallhorn, C.; Müller, G.; et al. Exploring determinants of Mediterranean lifestyle adherence: Findings from the multinational MEDIET4ALL e-survey across ten Mediterranean and neighboring countries. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable diets: The Mediterranean diet as an example. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2285–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean diet and health: A comprehensive overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular health: A critical review. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikalidis, A.K.; Kelleher, A.H.; Kristo, A.S. Mediterranean diet. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Trichopoulou, A.; Panza, F. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between adherence to Mediterranean diet with physical performance and cognitive function in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Lista, J.; Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Fuentes, F.; Garcia-Rios, A.; Ortiz-Morales, A.M.; Gonzalez-Requero, A.I.; Perez-Caballero, A.I.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; et al. Long-term secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet and a low-fat diet (CORDIOPREV): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Blanco Mejía, S.; Viguiliouk, E.; Khan, T.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Kahleova, H.; Rahelić, D.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Mediterranean diet, cardiovascular disease and mortality in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1207–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.A.; Padda, I.; Johal, G. Long-term impact of Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular disease prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damigou, E.; Faka, A.; Kouvari, M.; Anastasiou, C.; Kosti, R.I.; Chalkias, C.; Panagiotakos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean type of diet in the world: A geographical analysis based on a systematic review of 57 studies with 1,125,560 participants. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 74, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, G.; Yilmaz, H.Ö. Evaluation of the nutritional status, compliance with the Mediterranean diet, physical activity levels, and obesity prejudices of adolescents. Prog. Nutr. 2021, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ergul, F.; Sackan, F.; Koc, A.; Guney, I.; Kizilarslanoglu, M.C. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in Turkish hospitalized older adults and its association with hospital clinical outcomes. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 99, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülü, M.; Yapici, H.; Mainer-Pardos, E.; Alves, A.R.; Nobari, H. Investigation of obesity, eating behaviors and physical activity levels in rural and urban areas during the COVID-19 pandemic era: A study of Turkish adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, B.M. Dietary Intake Patterns and Mediterranean Diet Adherence Among Turkish Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Laiou, E.; Rapti, I.; Markozannes, G.; Cianferotti, L.; Fleig, L.; Warner, L.M.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Salvatore, S.; Trichopoulou, A.; et al. Social support, adherence to Mediterranean diet and physical activity in adults: Results from a community-based cross-sectional study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2020, 9, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamalaki, E.; Anastasiou, C.A.; Kosmidis, M.H.; Dardiotis, E.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M.; Sakka, P.; Scarmeas, N.; Yannakoulia, M. Social life characteristics in relation to adherence to the Mediterranean diet in older adults: Findings from the Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) study. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassıbaş, E.; Bölükbaşı, H. Evaluation of adherence to the Mediterranean diet with sustainable nutrition knowledge and environmentally responsible food choices. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, C.A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Jaalouk, D.; Kremers, S.P.; Oenema, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among adults in Mediterranean countries: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3327–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza-Martí, A.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.; Hurtado-Sánchez, J.; Laguna-Pérez, A.; Ferrer-Cascales, R. Evaluation of Mediterranean diet adherence scores: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean diet: A literature review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Moreno-Franco, B.; Ordovás, J.M.; León, M.; Casasnovas, J.A.; Peñalvo, J.L. Design and development of an instrument to measure overall lifestyle habits for epidemiological research: The Mediterranean Lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cemali, Ö.; Çelik, E.; Akdevelioğlu, Y. Validity and reliability study of the Mediterranean Lifestyle Index: Turkish adaptation. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2024, 19, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.L.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglam, M.; Arikan, H.; Savci, S.; Inal-Ince, D.; Bosnak-Guclu, M.; Karabulut, E.; Tokgozoglu, L. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: Reliability and validity of the Turkish version. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2010, 111, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäder, U.; Martin, B.W.; Schutz, Y.; Marti, B. Validity of four short physical activity questionnaires in middle-aged persons. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2006, 38, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Brach, M.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insight from the ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. Biol. Sport 2021, 38, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Urban Population (% of Total Population)—Türkiye. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=TR (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Statista. Share of the Population in Germany Aged 65 Years and Older from 1991 to 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1127844/population-share-aged-65-and-older-germany/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Worldometers. Turkey Demographics 2025 (Population, Age, Sex, Trends). 2025. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/turkey-demographics/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Schienkiewitz, A.; Kuhnert, R.; Blume, M.; Mensink, G.B. Overweight and obesity among adults in Germany—Results from GEDA 2019/2020-EHIS. J Health Monit. 2022, 7, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Hayretdağ, C. Anatomy of a nation: Exploring weight, height, and BMI variations among Turkish adults (2008-2022). Med. Sci. Discov. 2023, 10, 945–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2023: Türkiye—Country Note. 2023. Available online: https://gpseducation.oecd.org/Content/EAGCountryNotes/EAG2023_CN_TUR_pdf.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- OECD. Marriage and Divorce Rates in OECD Countries. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/family-database/sf_3_1_marriage_and_divorce_rates.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK). Marriage and Divorce Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Marriage-and-Divorce-Statistics-2022-49437 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Destatis. Consumer Price Index: Inflation Rate in Germany. 2024. Available online: https://www.destatis.de (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Palaz, F.S. The social networks and engagements of older Turkish migrants in Germany. Open J. Sociol. Stud. 2020, 4, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK). Labour Force Statistics, Quarter II: April–June, 2025. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Labour-Force-Statistics-Quarter-II:-April-June,-2025-54070 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Destatis. Labour Market Trends: Unemployment Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Labour/Labour-Market/Unemployment/_node.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- OECD. Unemployment Rates Updated: December 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/insights/statistical-releases/2024/12/unemployment-rates-updated-december-2024.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- WorldPopulationReview. Median Age by Country 2024. 2024. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/median-age (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Worldostats. Median Age by Country 2025. 9 January 2025. Available online: https://worldostats.com/country-stats/median-age-by-country/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. Türkiye: Global Tobacco Control Report 2023 Country Profile. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/country-profiles/tobacco/gtcr-2023/tobacco-2023-tur.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Kwong, E.J.L.; Whiting, S.; Bunge, A.C.; Leven, Y.; Breda, J.; Rakovac, I.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Wickramasinghe, K. Population-level salt intake in the WHO European Region in 2022: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26 (Suppl. 1), S6–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabasakal-Cetin, A.; Aksaray, B.; Sen, G. The role of food literacy and sustainable and healthy eating behaviors in ultra-processed foods consumption of undergraduate students. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 119, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Wine Per Capita Consumption in Germany from 2000 to 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/508812/wine-per-capita-consumption-germany/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Helgi Library. Wine Consumption Per Capita in Türkiye. 2021. Available online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/wine-consumption-per-capita/Türkiye/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Research and Markets. Germany Carbonated Soft Drinks Market: Summary, Trends, and Forecast. November 2023. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5782219/germany-carbonated-soft-drinks-market-summary (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- WMStrategy. Türkiye Carbonated Soft Drinks Market: Market Analysis, Size, and Forecast Until 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.wm-strategy.com/Türkiye-carbonated-soft-drinks-market-market-analysis-size-trends-consumption-insights-opportunities-challenges-and-forecast-until-2024 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S. Sedentary behavior and physical activity are associated with risk of depression among adult and older populations: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1542340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Hermassi, S.; Kolahi, A.-A.; Mansournia, M.; Jahrami, H.; Boukhris, O.; Boujelbane, M.; Glenn, J.; Clark, C.; et al. Global disease burden attributed to low physical activity in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: Insights from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. Biol. Sport 2023, 40, 835–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity Factsheet—Germany 2021. 31 May 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/m/item/physical-activity-factsheet-germany-2021 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Eurostat. Physical Activity and Sport Participation in Europe. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=412724 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Rütten, A. National Recommendations for Physical Activity and Physical Activity Promotion; FAU University Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Karaca Çelik, K.E.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M.; Uçar, N.; Soriano, J.M.; İnce Palamutoğlu, M.; Baş, M.; Toprak, D.; Hajhamidiasl, L.; Erol Doğan, Ö.; Doğan, M. Obesity prevalence, nutritional status, and physical activity levels in Turkish adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1438054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, N.S.; Karacabey, K. Türkiye ve Almanya’da okuyan beden eğitimi ve spor yüksekokulu öğrencilerinin vücut kompozisyonu, fiziksel aktivite düzeyi ve yaşam kalitesinin değerlendirilmesi. Spor Eğitim Derg. 2019, 3, 146–161. [Google Scholar]

- INRIX. INRIX 2023 Global Traffic Scorecard: Ranking the World’s Most Congested Cities. 2023. Available online: https://inrix.com/scorecard (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Yılmaz, M.; Yıldızer, G.; Uçar, D.E.; Yılmaz, İ. Differences in perceived physical activity constraints between Turkish and 4th generation Turkish-German young adults. Kinesiol. Slov. 2023, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncoso Parady, G.F. A comparative study of contact frequencies among social network members in five countries. In Proceedings of the 99th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board: New Mobility and Transportation Technology Takeaways (TRB 2020), Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2020. 20-00676. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hermoso, A.; Ezzatvar, Y.; López-Gil, J.F.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Olloquequi, J.; Izquierdo, M. Is adherence to the Mediterranean diet associated with healthy habits and physical fitness? A systematic review and meta-analysis including 565 421 youths. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1433–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.; Afonso, C.; Borges, N.; Santos, A.; Moreira, P.; Padrão, P.; Negrão, R.; Amaral, T.F. Adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern and functional parameters: A cross-sectional study in an older population. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júdice, P.B.; Carraça, E.V.; Santos, I.; Silva, A.M.; Sardinha, L.B. Different sedentary behavior domains present distinct associations with eating-related indicators. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaltopoulou, T.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Sergentanis, I.N.; Kosti, R.; Scarmeas, N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: A meta-analysis. Ann. Neurol. 2013, 74, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Bonanni, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Pounis, G.; Zito, F.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with a better health-related quality of life: A possible role of high dietary antioxidant content. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depboylu, G.Y.; Kaner, G. Younger age, higher father education level, and healthy lifestyle behaviors are associated with higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet in school-aged children. Nutrition 2023, 114, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, F.; Hernando, A.; Goulão, L.F.; Pinto, A.M.; Branco, A.; Cerqueira, A.; Galvão, C.; Guedes, F.B.; Bronze, M.R.; Viegas, W.; et al. Mediterranean diet adherence and nutritional literacy: An observational cross-sectional study of the reality of university students in a COVID-19 pandemic context. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2023, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, G. Cooking and food skills and their relationship with adherence to the Mediterranean diet in young adults attending university: A cross-sectional study from Türkiye. Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Statistical Institute (TÜİK). Statistics on Elderly Population. 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Elderly-Statistics-2024-54079 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Aksoy, M.; Kazkondu, İ. Türkiye’de yiyecek seçiminin bölgelere göre farklılaşması. J. Tour. Gastron. Stud. 2020, 8, 1306–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrmann, A.; Mensink, G.B.M. Cooking frequency in Germany. J. Health Monit. 2016, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möser, A. Food preparation patterns in German family households: An econometric approach with time budget data. Appetite 2010, 55, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Germany | Türkiye | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living Environment, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Urban environment | 850 (71.8) | 343 (56.3) | 507 (88.2) | |

| Suburban environment | 169 (14.3) | 132 (21.7) | 37 (6.4) | |

| Rural environment | 165 (13.9) | 134 (22.0) | 31 (5.4) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.675 | |||

| Male | 560 (47.5) | 284 (46.9) | 276 (48.1) | |

| Female | 620 (52.5) | 322 (53.1) | 298 (51.9) | |

| Age Category, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 18–35 years | 663 (56.0) | 302 (49.6) | 361 (62.8) | |

| 36–55 years | 372 (31.4) | 178 (29.2) | 194 (33.7) | |

| 55+ years | 149 (12.6) | 129 (21.2) | 20 (3.5) | |

| BMI Category, n (%) | 0.046 | |||

| Underweight | 44 (3.7) | 14 (2.3) | 30 (5.2) | |

| Normal Weight | 608 (51.4) | 323 (53.0) | 285 (49.6) | |

| Overweight | 371 (31.3) | 186 (30.5) | 185 (32.2) | |

| Obesity | 161 (13.6) | 86 (14.1) | 75 (13.0) | |

| Education, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| No schooling completed | 81 (6.8) | 9 (1.5) | 72 (12.5) | |

| High school graduation | 296 (25.0) | 163 (26.8) | 133 (23.1) | |

| Professional degree | 193 (16.3) | 170 (27.9) | 23 (4.0) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 436 (36.8) | 151 (24.8) | 285 (49.6) | |

| Master’s degree/doctorate | 178 (15.0) | 116 (19.0) | 62 (10.8) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Single | 570 (48.1) | 320 (52.5) | 250 (43.5) | |

| Married living as a couple | 525 (44.3) | 221 (36.3) | 304 (52.9) | |

| Widowed, divorced, separated | 89 (7.5) | 68 (11.2) | 21 (3.7) | |

| Employment Status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Employed | 772 (67.0) | 397 (66.3) | 375 (67.8) | |

| Unemployed | 82 (7.1) | 22 (3.7) | 60 (10.8) | |

| Student | 232 (20.1) | 126 (21.0) | 106 (19.2) | |

| Retired | 66 (5.7) | 54 (9.0) | 12 (2.2) | |

| Health Status, n (%) | 0.291 | |||

| Healthy | 896 (79.4) | 450 (79.6) | 446 (79.2) | |

| At risk | 152 (13.5) | 81 (14.3) | 71 (12.6) | |

| With diseases | 80 (7.1) | 34 (6.0) | 46 (8.2) | |

| Smoking Habits, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes (cigarettes) | 344 (29.1) | 152 (25.0) | 192 (33.4) | |

| Yes (shisha) | 130 (11.0) | 28 (4.6) | 102 (17.7) | |

| No | 710 (60.0) | 429 (70.4) | 281 (48.9) |

| Criteria for 1 Point | Total | Germany | Türkiye | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Mediterranean Food Consumption, n (%) for 1 point | |||||

| Sweets | ≤2 servings/week | 663 (56.0) | 328 (53.9) | 335 (58.3) | 0.127 |

| Red meat | <2 servings/week | 639 (54.0) | 351 (57.6) | 288 (50.1) | 0.009 |

| Processed meat | ≤1 serving/week | 727 (61.4) | 301 (49.4) | 426 (74.1) | <0.001 |

| Eggs | 2–4 servings/week | 424 (35.8) | 249 (40.9) | 175 (30.4) | <0.001 |

| Legumes | ≥2 servings/week | 684 (57.8) | 285 (46.8) | 399 (69.4) | <0.001 |

| White meat | 2 servings/week | 265 (22.4) | 108 (17.7) | 157 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| Fish | ≥2 servings/week | 220 (18.6) | 128 (21.0) | 92 (16.0) | 0.027 |

| Potatoes | ≤3 servings/week | 1000 (84.5) | 511 (83.9) | 489 (85.0) | 0.590 |

| Dairy | 2 servings/d | 170 (14.4) | 75 (12.3) | 95 (16.5) | 0.039 |

| Nuts/Olives | 1–2 servings/d | 710 (60.0) | 334 (54.8) | 376 (65.4) | <0.001 |

| Herbs/Spices | ≥1 serving/d | 1063 (89.8) | 548 (90.0) | 515 (89.6) | 0.812 |

| Fruits | 3–6 servings/d | 166 (14.0) | 97 (15.9) | 69 (12.0) | 0.052 |

| Vegetables | ≥2 servings/d | 503 (42.5) | 265 (43.5) | 238 (41.4) | 0.460 |

| Olive oil | ≥3 servings/d | 271 (22.9) | 104 (17.1) | 167 (29.0) | <0.001 |

| Cereals | 3–6 servings/d | 329 (27.8) | 201 (33.0) | 128 (22.3) | <0.001 |

| Block 1: Total Score | 6.38 ± 1.98 | 6.87 ± 1.73 | <0.001 | ||

| Block 2: Mediterranean Dietary Habits, n (%) for 1 point | |||||

| Drink | 6–8 servings/d or ≥3 servings/week | 988 (83.4) | 505 (82.9) | 483 (84.0) | 0.618 |

| Wine | 1–2 servings/d | 54 (4.6) | 43 (7.1) | 11 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Salt | Limit salt: Yes | 759 (64.1) | 358 (58.8) | 401 (69.7) | <0.001 |

| Grain products | Yes/fiber > 25 g/d | 743 (62.8) | 363 (59.6) | 380 (66.1) | 0.021 |

| Snacks | ≤2 servings/week | 783 (66.1) | 386 (63.4) | 397 (69.0) | 0.040 |

| Nibbling | Limit nibbling between meals: Yes | 721 (60.9) | 387 (63.5) | 334 (58.1) | 0.054 |

| Sugar | Limit sugar in beverages: Yes | 851 (71.9) | 472 (77.5) | 379 (65.9) | <0.001 |

| Block 2: Total Score | 4.13 ± 1.68 | 4.15 ± 1.57 | 0.835 | ||

| Block 3: Physical activity, rest, Social Habits, and Conviviality, n (%) for 1 point | |||||

| Physical activity | >150 min/week or 30 min/d | 789 (66.6) | 423 (69.5) | 366 (63.7) | 0.034 |

| Nap | Yes | 352 (29.7) | 204 (33.5) | 148 (25.7) | 0.004 |

| Sleep | 6–8 h/d | 884 (74.7) | 477 (78.3) | 407 (70.8) | 0.003 |

| Watching TV | <1 h/d | 223 (18.8) | 93 (15.3) | 130 (22.6) | 0.001 |

| Time with friends | ≥2 h/weekend | 872 (73.6) | 458 (75.2) | 414 (72.0) | 0.211 |

| Team sports | ≥2 h/week | 319 (26.9) | 163 (26.8) | 156 (27.1) | 0.887 |

| Block 3: Total Score | 2.99 ± 1.27 | 2.82 ± 1.30 | 0.027 | ||

| MedLife Index Categories | |||||

| Low | 391 (33.0) | 220 (36.1) | 171 (29.7) * | 0.005 | |

| Medium | 589 (49.7) | 275 (45.2) | 314 (54.6) * | ||

| High | 204 (17.2) | 114 (18.7) | 90 (15.7) * | ||

| Total | Germany | Türkiye | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MedDiet awareness, n (%) | 571 | 342 (55.5) | 229 (38.4) | <0.001 | |

| MBQ | Attitudes (suitability, taste, restrictive, food waste) | 1000 | 495 (80.4) | 505 (84.7) | 0.045 |

| Social norms (food culture) | 996 | 546 (88.6) | 450 (75.5) | <0.001 | |

| Low motivation | 209 | 117 (19) | 92 (15.4) | 0.101 | |

| Price affordability | 915 | 422 (68.5) | 493 (82.7) | <0.001 | |

| Time/effort for consuming | 304 | 198 (32.1) | 106 (17.8) | <0.001 | |

| Low accessibility/availability of Mediterranean food | 1060 | 532 (86.4) | 528 (88.6) | 0.242 | |

| Lack of knowledge and cooking skills | 207 | 123 (20) | 84 (14.1) | 0.007 | |

| Food allergies and intolerances | 146 | 101 (16.4) | 45 (7.6) | <0.001 | |

| Cultural and/or religious reason | 1212 | 594 (96.4) | 531 (89.1) | <0.001 | |

| Medical reason | 1163 | 569 (92.4) | 567 (95.1) | 0.047 | |

| Individual beliefs (e.g., vegan and vegetarian) | 1108 | 536 (87) | 572 (96) | <0.001 | |

| Taste dislike | 251 | 119 (19.3) | 132 (22.1) | 0.224 | |

| Other | 21 | 13 (2.1) | 8 (1.3) | 0.306 | |

| MBQ total score | 7.09 ± 1.24 | 6.9 ± 1.21 | 0.16 | ||

| Total | Germany | Türkiye | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants’ categories according to the IPAQ-SF score, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Low Activities | 675 (57.0) | 271 (44.5) | 404 (70.3) | |

| Moderate Activities | 218 (18.4) | 141 (23.2) | 77 (13.4) | |

| High Activities | 291 (24.6) | 197 (32.3) | 94 (16.3) | |

| Participants’ categories according to the SSPQ-L score, n (%) | 0.006 | |||

| Never | 13 (1.1) | 8 (1.3) | 5 (0.9) | |

| Rarely | 233 (20.2) | 137 (22.9) | 96 (17.3) | |

| Sometimes | 574 (49.7) | 306 (51.2) | 268 (48.2) | |

| Often | 290 (25.1) | 125 (20.9) | 165 (29.7) | |

| All Times | 44 (3.8) | 22 (3.7) | 22 (4.0) |

| Variables | MedLife | IPAQ-SF | SSPQ-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| German responders | |||

| MedLife | - | ||

| IPAQ-SF | 0.092 * | - | |

| SSPQ-L | 0.349 ** | 0.159 ** | - |

| Turkish responders | |||

| MedLife | - | ||

| IPAQ-SF | 0.071 | - | |

| SSPQ-L | 0.093 * | 0.178 ** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ammar, A.; Uyar, A.M.; Salem, A.; Álvarez-Córdova, L.; Boujelbane, M.A.; Trabelsi, K.; Orhan, B.E.; Heydenreich, J.; Schallhorn, C.; Grosso, G.; et al. Adherence to Mediterranean Healthy Lifestyle Patterns and Potential Barriers: A Comparative Study of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, and Social Participation Between German and Turkish Populations. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213338

Ammar A, Uyar AM, Salem A, Álvarez-Córdova L, Boujelbane MA, Trabelsi K, Orhan BE, Heydenreich J, Schallhorn C, Grosso G, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean Healthy Lifestyle Patterns and Potential Barriers: A Comparative Study of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, and Social Participation Between German and Turkish Populations. Nutrients. 2025; 17(21):3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213338

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmmar, Achraf, Ayse Merve Uyar, Atef Salem, Ludwig Álvarez-Córdova, Mohamed Ali Boujelbane, Khaled Trabelsi, Bekir Erhan Orhan, Juliane Heydenreich, Christiana Schallhorn, Giuseppe Grosso, and et al. 2025. "Adherence to Mediterranean Healthy Lifestyle Patterns and Potential Barriers: A Comparative Study of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, and Social Participation Between German and Turkish Populations" Nutrients 17, no. 21: 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213338

APA StyleAmmar, A., Uyar, A. M., Salem, A., Álvarez-Córdova, L., Boujelbane, M. A., Trabelsi, K., Orhan, B. E., Heydenreich, J., Schallhorn, C., Grosso, G., Frias-Toral, E., Jahrami, H., Zmijewski, P., Chtourou, H., & Schöllhorn, W. I. (2025). Adherence to Mediterranean Healthy Lifestyle Patterns and Potential Barriers: A Comparative Study of Dietary Habits, Physical Activity, and Social Participation Between German and Turkish Populations. Nutrients, 17(21), 3338. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17213338