Early Maladaptive Schemas, Emotion Regulation, Stress, Social Support, and Lifestyle Factors as Predictors of Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: Evidence from a Large Community Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Eating Behavior

1.3. Emotion Regulation and Perceived Stress

1.4. Social Support as a Protective Factor

1.5. Diet Quality and Objective Dietary Measures

1.6. Role of Physical Activity

1.7. Rationale and Aims of the Present Study

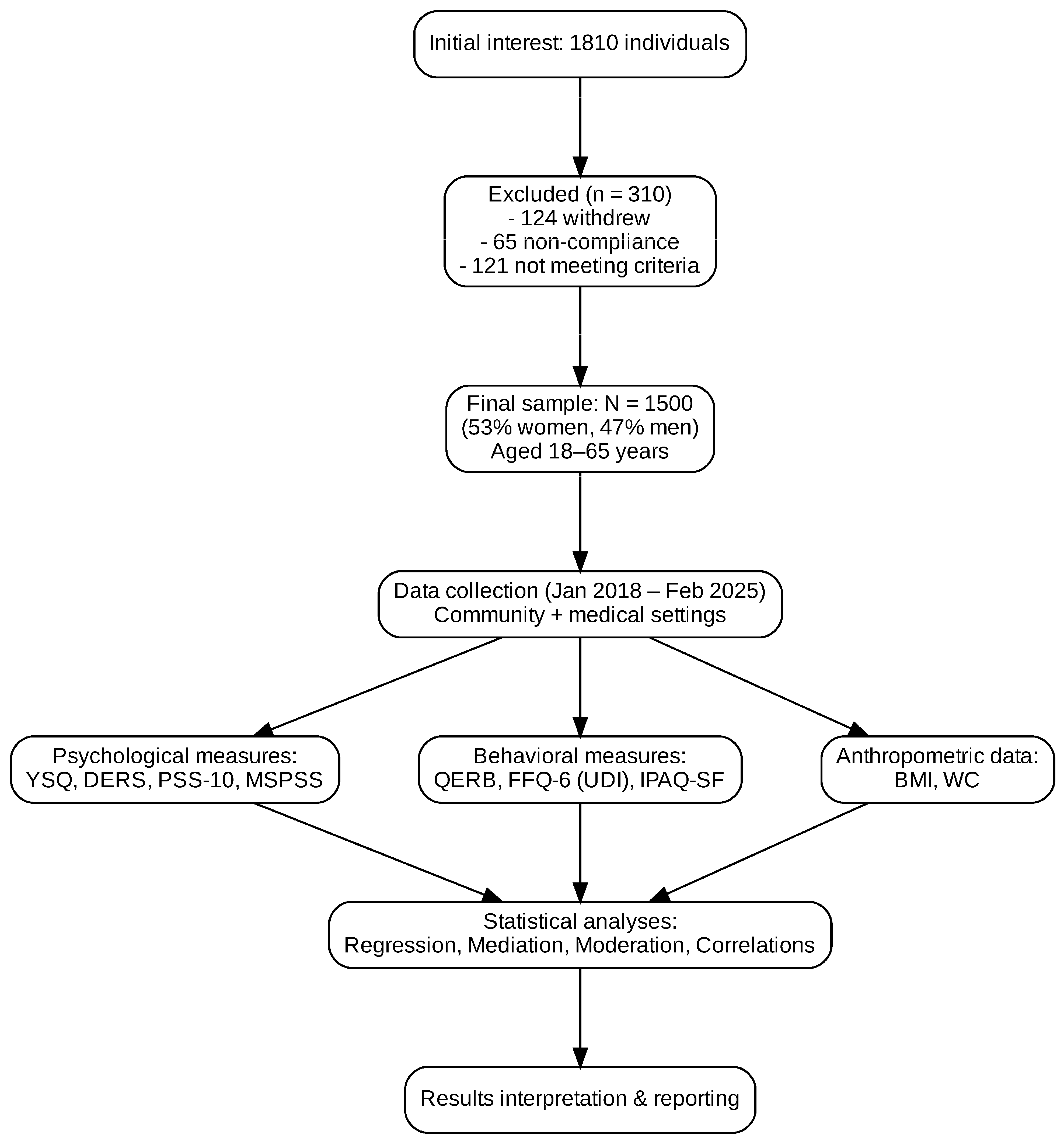

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Screening for Psychiatric and Medical Conditions

2.4. Anthropometric Assessment

2.5. Measures

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Statistical Analyses

3.2. Mediation and Moderation Analyses

3.3. Associations with Physical Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamulka, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Hoffmann, M.; Kowalkowska, J.; Gutkowska, K. Effect of an Education Program on Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes toward Nutrition, Diet Quality, Lifestyle, and Body Composition in Polish Teenagers: The ABC of Healthy Eating Project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasolato, R.; De Felice, M.; Barbui, C.; Bertani, M.; Bonora, F.; Castellazzi, M.; Castelli, S.; Cristofalo, D.; Dall’Agnola, R.B.; Ruggeri, M.; et al. Early Maladaptive Schemas Mediate the Relationship between Severe Childhood Trauma and Eating Disorder Symptoms: Evidence from an Exploratory Study. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Wang, H.; Du, W.; Zhang, B. Insufficient Capacity to Cope with Stressors Decreases Dietary Quality in Females. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.; Cason, L.; Huckstepp, T.; Stallman, H.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Millear, P.; Mason, J.; Wood, A.; Allen, A. Early Maladaptive Schemas in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2022, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.E.; Klosko, J.S.; Weishaar, M.E. Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington, P.D.; Bishop, A.; Younan, R. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Early Maladaptive Schemas in Adulthood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2021, 28, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.S.; Huckstepp, T.; Allen, A.; Louis, P.J.; Anijärv, T.E.; Hermens, D.F. Early Adaptive Schemas, Emotional Regulation, and Cognitive Flexibility in Eating Disorders: Subtype-Specific Predictors Using Hierarchical Linear Regression. Eat. Weight Disord. 2024, 29, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, A.; Kavanagh, P.S.; Murray, K.; Mak, A.S. Emotion Regulation as a Mediator between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Youth. J. Behav. Cogn. Ther. 2022, 32, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unoka, Z.; Tölgyes, T.; Czobor, P.; Simon, L. Eating Disorder Behavior and Early Maladaptive Schemas in Subgroups of Eating Disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, K.; Özgörüş, Z. Investigation of the Relationship between Early Maladaptive Schemas, Temperament and Eating Attitude in Adults. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, B.; Tenore, K.; Mancini, F. Early Maladaptive Schemas in Overweight and Obesity: A Schema-Mode Model. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, A.; Bär, H.E.; Rijkeboer, M.M.; Lobbestael, J. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Schema Modes in Clinical Disorders: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Psychother. 2023, 96, 716–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Travica, N.; Dissanayaka, T.; Ashtree, D.N.; Gauci, S.; Lotfaliany, M.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.N.; Marx, W. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stariolo, J.B.; Lemos, T.C.; Khandpur, N.; Pereira, M.G.; Oliveira, L.; Mocaiber, I.; Ramos, T.C.; David, I.A. Addiction to Ultra-Processed Foods as a Mediator between Psychological Stress and Emotional Eating during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2024, 37, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Jesus, J.I.F.; Monfort-Pañego, M.; Alves Santos, G.V.; Monteiro, Y.C.; Nogueira, S.M.; Rayanne e Silva, P.; Noll, M. Food, Quality of Life and Mental Health: A Cross-Sectional Study with Federal Education Workers. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Chen, X.; Howland, S.; Danza, P.; Niu, Z.; Gauderman, W.J.; Habre, R.; McConnell, R.; Yan, M.; Whitfield, L.; et al. Perceived Stress from Childhood to Adulthood and Cardiometabolic End Points in Young Adulthood: An 18-Year Prospective Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Enden, G.; Geyskens, K.; Goukens, C. Feeling Well Surrounded: Perceived Societal Support Fosters Healthy Eating. J. Health Psychol. 2023, 29, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, A.; Smith, M.L.; Lee, S.; Towne, S.D.; Ory, M.G. The Role of Improved Social Support for Healthy Eating in a Lifestyle Intervention: Texercise Select. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmann, M.M.; Hagerman, C.J.; Milliron, B.-J.; Butryn, M.L. The Role of Household Social Support and Undermining in Dietary Change. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024, 31, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.M.; Fursland, A. New Understandings Meet Old Treatments: Putting a Contemporary Face on Established Protocols. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Wądołowska, L. The 72-Item Semi-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (72-Item SQ-FFQ) for Polish Young Adults: Reproducibility and Relative Validity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedźwiedzka, E.; Wądołowska, L.; Kowalkowska, J. Reproducibility of a Non-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (62-Item FFQ-6) and PCA-Driven Dietary Pattern Identification in 13–21-Year-Old Females. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPAQ Research Committee. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Short and Long Forms. 2005. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Obara-Gołębiowska, M. Psychological Predictors of Eating Behavior: The Role of Maladaptive Schemas and Emotion Regulation across BMI, Gender, and Age Groups. Appetite 2025, 215, 108243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obara-Gołębiowska, M.; Przybyłowicz, K.E.; Danielewicz, A.; Sawicki, T. Body Mass as a Result of Psychological, Lifestyle and Genetic Determinants. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staniaszek, K.; Popiel, A. Development and Validation of the Polish Experimental Short Version of the Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ-ES-PL). Rocz. Psychol. 2017, 20, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, W.Ł. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation and Problem Drinking in Young Women: The Mediating Effect of Metacognitions about Alcohol Use. Addict. Behav. 2016, 54, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N. Psychology of Excessive Eating; Lodz University Publisher: Łódź, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogińska-Bulik, N.; Juczyński, Z. Perceived Stress Scale—PSS-10. In Tools for Measuring Stress and Coping with Stress; Psychological Test Laboratory of the Polish Psychological Association: Warsaw, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszman, K.; Przybyła-Basista, H. Polish Adaptation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). Pol. Psychol. Forum 2017, 22, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, E.; Stupnicki, R.; Gajewski, A.K. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)—Polish Version. Wych. Fiz. Sport 2007, 51, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, Y.; Ohya, A. A cross-sectional examination of the simultaneous association of four emotion regulation strategies with abnormal eating behaviours among women in Japan. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Luadlai, S.; Liu, J.; Tuicomepee, A. The relationships between affect, emotion regulation, and overeating in Thai culture. Int. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 13, 51–67. Available online: https://so06.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/IJBS/article/view/125187 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Favieri, F.; Marini, A.; Casagrande, M. Emotional regulation and overeating behaviors in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arslan, M.; Yabancı Ayhan, N.; Çevik, E.; Sarıyer, E.T.; Çolak, H. Effect of emotion regulation difficulty on eating attitudes and body mass index in university students: A cross-sectional study. J. Men’s Health 2022, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermans, M.; Jonker, N.; de Jong, P. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation skills are associated with food intake following a hunger-induced increase in negative emotions. Appetite 2024, 193, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadidy, H.S.M.A.; Giacomini, G.; Prinzivalli, A.; Ragusa, P.; Gianino, M.M. Which factors influence emotional overeating among workers and students? Is online food delivery consumption involved? Results from the DELIvery Choice in OUr Society (DELICIOUS) cross-sectional study. Appetite 2025, 206, 107814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female/Male | 795 (53.0)/705 (47.0) |

| Age group | Younger (18–35)/Older (36–65) | 825 (55.0)/675 (45.0) |

| Residence | Urban/Rural | 870 (58.0)/630 (42.0) |

| Education | Higher/Secondary | 675 (45.0)/825 (55.0) |

| Variable | Female M (SD) | Male M (SD) | t | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QERB—Emotional Overeating | 6.06 (1.68) | 5.34 (1.69) | 8.25 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| QERB—Habitual Overeating | 6.13 (1.74) | 5.36 (1.69) | 8.72 | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| QERB—Dietary Restraint | 6.04 (1.68) | 5.30 (1.67) | 8.51 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| DERS—Total | 115.30 (12.36) | 107.76 (12.80) | 11.59 | <0.001 | 0.60 |

| PSS-10—Perceived Stress | 23.32 (3.97) | 20.63 (4.11) | 12.87 | <0.001 | 0.67 |

| MSPSS—Perceived Social Support | 65.15 (8.18) | 59.33 (8.23) | 13.72 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| UDI—Unhealthy Diet Index | 3.87 (0.40) | 3.80 (0.43) | 3.18 | 0.001 | 0.16 |

| IPAQ—Total MET-min/week | 5084.78 (1563.35) | 4910.89 (1531.06) | 2.18 | 0.030 | 0.11 |

| IPAQ—Sitting Time (hours/day) | 4.27 (0.55) | 4.34 (0.53) | −2.47 | 0.014 | −0.13 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.49 (4.67) | 26.37 (4.94) | −3.56 | <0.001 | −0.18 |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 96.00 (13.08) | 84.05 (13.89) | 17.12 | <0.001 | 0.89 |

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.92 | 4.82 | 18.54 | 34.97 | 0.26 | −1.17 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.22 | 14.74 | 60.00 | 131.10 | 0.12 | −0.56 |

| QERB—Emotional Overeating | 7.71 | 1.72 | 2.15 | 9.86 | 0.11 | −0.96 |

| QERB—Habitual Overeating | 5.76 | 1.76 | 2.08 | 9.83 | 0.10 | −1.09 |

| QERB—Dietary Restraint | 5.68 | 1.72 | 2.02 | 9.76 | 0.16 | −0.92 |

| DERS—Total | 111.65 | 13.12 | 77.05 | 147.60 | −0.03 | −0.41 |

| PSS-10 | 22.02 | 4.25 | 10.72 | 33.12 | −0.04 | −0.43 |

| MSPSS—Total | 62.33 | 8.70 | 41.50 | 83.86 | 0.01 | −0.40 |

| YSQ—Total | 71.65 | 8.46 | 52.61 | 94.60 | 0.03 | −0.59 |

| UDI—Unhealthy Diet Index | 3.24 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 5.75 | 0.27 | −0.65 |

| IPAQ—Total MET-min/week | 3125.48 | 1742.61 | 480.00 | 9640.00 | 0.41 | −0.54 |

| IPAQ—Sitting Time (hours/week) | 39.62 | 11.75 | 10.00 | 75.00 | 0.22 | −0.71 |

| Pathway | β | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YSQ → DERS | 0.42 | 0.03 | [0.36, 0.48] | <0.001 |

| DERS → Emotional Overeating | 0.27 | 0.03 | [0.22, 0.33] | <0.001 |

| YSQ → Emotional Overeating (direct) | 0.18 | 0.04 | [0.10, 0.26] | <0.001 |

| DERS → UDI | 0.19 | 0.04 | [0.12, 0.26] | <0.001 |

| YSQ → UDI (direct) | 0.14 | 0.05 | [0.05, 0.23] | <0.01 |

| Stress × YSQ → DERS | 0.08 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.12] | <0.01 |

| Social Support × YSQ → DERS | −0.09 | 0.02 | [−0.13, −0.05] | <0.01 |

| Predictor | Outcome: UDI | β | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total MET-min/week (IPAQ) | −0.14 | 0.04 | <0.01 | |

| Sitting time (hours/week) | 0.12 | 0.04 | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obara-Gołębiowska, M. Early Maladaptive Schemas, Emotion Regulation, Stress, Social Support, and Lifestyle Factors as Predictors of Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: Evidence from a Large Community Sample. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203188

Obara-Gołębiowska M. Early Maladaptive Schemas, Emotion Regulation, Stress, Social Support, and Lifestyle Factors as Predictors of Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: Evidence from a Large Community Sample. Nutrients. 2025; 17(20):3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203188

Chicago/Turabian StyleObara-Gołębiowska, Małgorzata. 2025. "Early Maladaptive Schemas, Emotion Regulation, Stress, Social Support, and Lifestyle Factors as Predictors of Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: Evidence from a Large Community Sample" Nutrients 17, no. 20: 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203188

APA StyleObara-Gołębiowska, M. (2025). Early Maladaptive Schemas, Emotion Regulation, Stress, Social Support, and Lifestyle Factors as Predictors of Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: Evidence from a Large Community Sample. Nutrients, 17(20), 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17203188