Dieting Practices of Adolescents Seeking Obesity Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

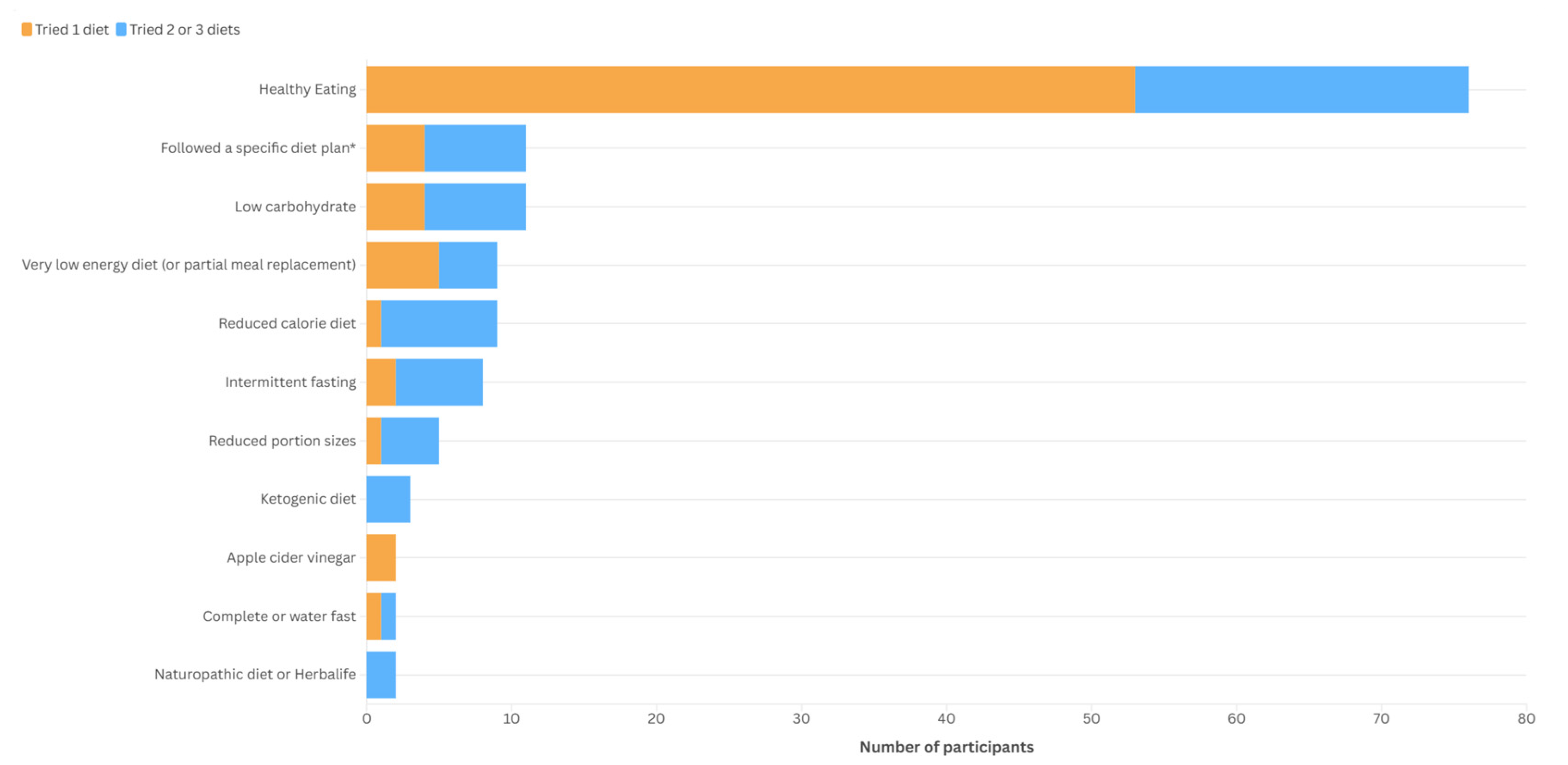

3.1. Types of Diets

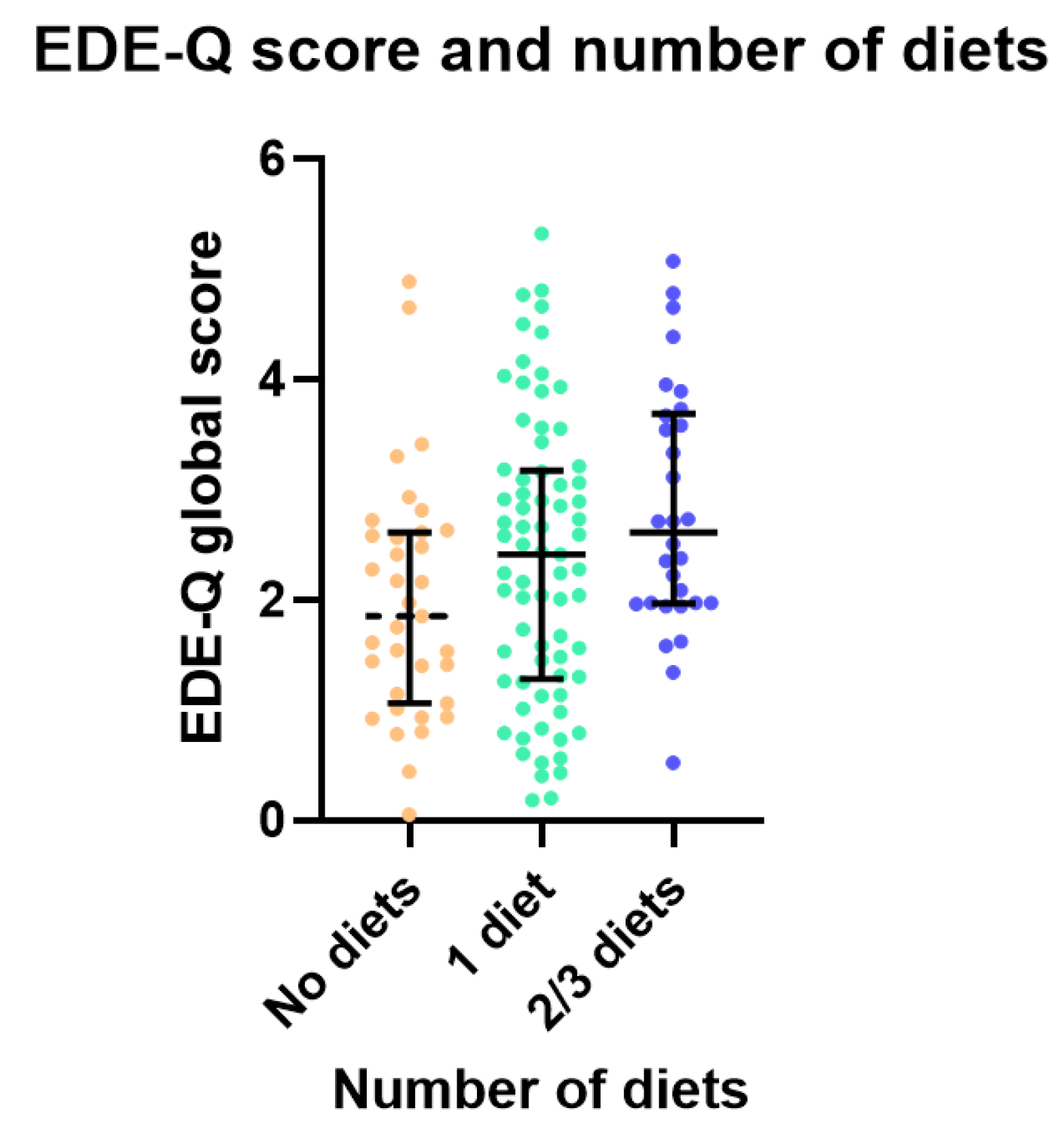

3.2. Psychosocial Wellbeing and Eating Behaviours

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| VLED | Very-Low-Energy Diet |

| EDE-Q | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire |

References

- Lobstein, T.; Brinsden, H. Atlas of Childhood Obesity; World Obesity Federation: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, N.B.; Baur, L.A.; Felix, J.F.; Hill, A.J.; Marcus, C.; Reinehr, T.; Summerbell, C.; Wabitsch, M. Child and adolescent obesity. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampl, S.E.; Hassink, S.G.; Skinner, A.C.; Armstrong, S.C.; Barlow, S.E.; Bolling, C.F.; Avila Edwards, K.C.; Eneli, I.; Hamre, R.; Joseph, M.M. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Pediatrics 2023, 15, e2022060640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in children and adolescents: Epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alman, K.L.; Lister, N.B.; Garnett, S.P.; Gow, M.L.; Aldwell, K.; Jebeile, H. Dietetic management of obesity and severe obesity in children and adolescents: A scoping review of guidelines. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMaster, C.M.; Calleja, E.; Cohen, J.; Alexander, S.; Denney-Wilson, E.; Baur, L.A. Current status of multi-disciplinary paediatric weight management services in Australia. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2021, 57, 1259–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.L.; Skelton, J.A.; Perrin, E.M.; Skinner, A.C. Behaviors and motivations for weight loss in children and adolescents. Obesity 2016, 24, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, J.C.; Bereket, A.; Bin-Abbas, B.; Chen, W.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Garibay Nieto, N.; López Siguero, J.P.; Maffeis, C.; Mooney, V.; Osorto, C.K. Misalignment among adolescents living with obesity, caregivers, and healthcare professionals: ACTION Teens global survey study. Pediatr. Obes. 2022, 17, e12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Guo, J.; Story, M.; Haines, J.; Eisenberg, M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: How do dieters fare 5 years later? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.E.; Austin, S.B.; Taylor, C.B.; Malspeis, S.; Rosner, B.; Rockett, H.R.; Gillman, M.W.; Colditz, G.A. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics 2003, 112, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Van Ryzin, M. A prospective test of the temporal sequencing of risk factor emergence in the dual pathway model of eating disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Puhl, R.M. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R. Associations between Body Appreciation and Disordered Eating in a Large Sample of Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, N.B.; Jebeile, H.; Truby, H.; Garnett, S.P.; Varady, K.A.; Cowell, C.T.; Collins, C.E.; Paxton, S.J.; Gow, M.L.; Brown, J.; et al. Fast track to health—Intermittent energy restriction in adolescents with obesity. A randomised controlled trial study protocol. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebeile, H.; Baur, L.A.; Kwok, C.; Alexander, S.; Brown, J.; Collins, C.E.; Cowell, C.T.; Day, K.; Garnett, S.P.; Gow, M.L.; et al. Symptoms of depression, eating disorders and binge eating in adolescents with obesity: Fast Track to Health Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lister, N.B.; Baur, L.A.; House, E.T.; Alexander, S.; Brown, J.; Collins, C.E.; Cowell, C.T.; Day, K.; Garnett, S.P.; Gow, M.L.; et al. Fast Track to Health. Intermittent energy restriction for adolescents with obesity. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.C.; Stewart, D.A.; Fairburn, C.G. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: Norms for young adolescent girls. Behav. Res. Ther. 2001, 39, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mond, J.; Hall, A.; Bentley, C.; Harrison, C.; Gratwick-Sarll, K.; Lewis, V. Eating-disordered behavior in adolescent boys: Eating disorder examination questionnaire norms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mina, A.; Hallit, S.; Rogoza, R.; Obeid, S.; Soufia, M. Binge eating behavior in a sample of Lebanese adolescents: Correlates and binge eating scale validation. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isnard, P.; Michel, G.; Frelut, M.-L.; Vila, G.; Falissard, B.; Naja, W.; Navarro, J.; Mouren-Simeoni, M.-C. Binge eating and psychopathology in severely obese adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 34, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, L.E.; Latner, J.D. Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity 2008, 16, S80–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberto, C.A.; Sysko, R.; Bush, J.; Pearl, R.; Puhl, R.M.; Schvey, N.A.; Dovidio, J.F. Clinical correlates of the weight bias internalization scale in a sample of obese adolescents seeking bariatric surgery. Obesity 2012, 20, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, L.; Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N. The body appreciation scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2005, 2, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobera, I.J.; Ríos, P.B. Spanish Version of the Body Appreciation Scale (BAS) for Adolescents. Span. J. Psychol. 2011, 14, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegal, K.M.; Wei, R.; Ogden, C.L.; Freedman, D.S.; Johnson, C.L.; Curtin, L.R. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index–for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1314–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, M.L.; Jebeile, H.; House, E.T.; Alexander, S.; Baur, L.A.; Brown, J.; Collins, C.E.; Cowell, C.T.; Day, K.; Garnett, S.P.; et al. Efficacy, Safety and Acceptability of a Very-Low-Energy Diet in Adolescents with Obesity: A Fast Track to Health Sub-Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Haines, J.; Story, M.; Eisenberg, M.E. Why Does Dieting Predict Weight Gain in Adolescents? Findings from Project EAT-II: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, J.H.; Shisslak, C.M.; Crago, M.A. Does Dieting Lead to Weight Gain? A Four-Year Longitudinal Study of Middle School Girls. Obesity 2006, 14, 2236–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, E.; Warnick, J.; Acharya, R.; Janicke, D. The use of internet sources for nutritional information is linked to weight perception disordered eating in young adolescents. Appetite 2020, 154, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebeile, H.; Partridge, S.R.; Gow, M.L.; Baur, L.A.; Lister, N.B. Adolescent exposure to weight loss imagery on Instagram: A content analysis of ‘top’ images. Child. Obes. 2021, 17, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, N.B.; Melville, H.; Jebeile, H. What adolescents see on Instagram: Content analysis of #intermittentfasting, #keto, and #lowcarb. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 81, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. ‘Strong is the new skinny’: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M.; Zaccardo, M. “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image 2015, 15, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, I.; McLachlan, A.C.; Lavis, T.; Tiggemann, M. The impact of different forms of #fitspiration imagery on body image, mood, and self-objectification among young women. Sex. Roles 2018, 78, 789–798. [Google Scholar]

| Variable, n = 141 | n(%) |

| Consulted a dietitian—yes | 68 (48.2%) |

| 23 (16.3%) |

| 44 (31.2%) |

| 3 (2.1%) |

| Number of diets trialled by adolescents,* n = 138 | n(%) |

| 0 | 35 (25.4%) |

| 1 | 73 (52.9%) |

| 2 | 26 (18.8%) |

| 3 | 4 (2.9%) |

| Previous diets, n = 138 * | |

| None | 35 (25.4%) |

| Healthy eating | 76 (55.1%) |

| Low carbohydrate | 11 (7.8%) |

| Followed a specific diet plan ** | 11 (8.0%) |

| Very-low-energy diet (or partial meal replacement) | 9 (6.5%) |

| Reduced-calorie diet (with calorie target) | 9 (6.5%) |

| Intermittent fasting | 8 (5.8%) |

| Ketogenic diet | 3 (2.2%) |

| Reduced portion sizes | 5 (3.6%) |

| Naturopathic diet or Herbalife | 2 (1.4%) |

| Apple cider vinegar | 2 (1.4%) |

| Complete or water fast | 2 (1.4%) |

| Variable, Mean (SD) | Non-Dieter, n = 35 | One Diet, n = 73 | Two–Three Diets, n = 30 | F(df) | ANOVA, p-Value for Difference Between Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 178 (14) | 179 (16) | 179 (14) | 0.059 (2135) | 0.943 |

| BMI, as %95th percentile | 128 (16) | 131 (16) | 129 (14) | 0.617 (2135) | 0.541 |

| BES score * | 10.16 (8.11) | 11.48 (7.83) | 13.09 (7.08) | 1.153 (2129) | 0.319 |

| EDE-Q global score | 1.98 (1.08) | 2.36 (1.28) | 2.81 (1.12) | 3.871 (2135) | 0.023 |

| Weight bias internalisation score | 3.86 (1.35) | 3.95 (1.24) | 4.15 (1.26) | 0.462 (2131) | 0.631 |

| Body appreciation scale | 3.15 (0.83) | 3.21 (0.82) | 3.11 (0.81) | 0.176 (2132) | 0.839 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jebeile, H.; House, E.T.; Baur, L.A.; Kwok, C.; Collins, C.E.; Garnett, S.P.; Lister, N.B., on behalf of the Fast Track to Health Study Team. Dieting Practices of Adolescents Seeking Obesity Treatment. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3100. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193100

Jebeile H, House ET, Baur LA, Kwok C, Collins CE, Garnett SP, Lister NB on behalf of the Fast Track to Health Study Team. Dieting Practices of Adolescents Seeking Obesity Treatment. Nutrients. 2025; 17(19):3100. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193100

Chicago/Turabian StyleJebeile, Hiba, Eve T. House, Louise A. Baur, Cathy Kwok, Clare E. Collins, Sarah P. Garnett, and Natalie B. Lister on behalf of the Fast Track to Health Study Team. 2025. "Dieting Practices of Adolescents Seeking Obesity Treatment" Nutrients 17, no. 19: 3100. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193100

APA StyleJebeile, H., House, E. T., Baur, L. A., Kwok, C., Collins, C. E., Garnett, S. P., & Lister, N. B., on behalf of the Fast Track to Health Study Team. (2025). Dieting Practices of Adolescents Seeking Obesity Treatment. Nutrients, 17(19), 3100. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193100