Health Literacy and Nutrition of Adolescent Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection Period and Ethics Statement

2.3. Methods

2.4. Participants’ Characteristics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Results of Health Literacy Screening

3.2. Results of Diet Adherence Screening

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Rheenen, P.F.; Aloi, M.; Assa, A.; Bronsky, J.; Escher, J.C.; Fagerberg, U.L.; Gasparetto, M.; Gerasimidis, K.; Griffiths, A.; Henderson, P.; et al. The Medical Management of Paediatric Crohn’s Disease: An ECCO-ESPGHAN Guideline Update. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, jjaa161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torres, L.; Moreno-Álvarez, A.; Fernández-Lorenzo, A.E.; Leis, R.; Solar-Boga, A. The Role of Partial Enteral Nutrition for Induction of Remission in Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigall Boneh, R.; Westoby, C.; Oseran, I.; Sarbagili-Shabat, C.; Albenberg, L.G.; Lionetti, P.; Manuel Navas-López, V.; Martín-de-Carpi, J.; Yanai, H.; Maharshak, N.; et al. The Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet: A Comprehensive Review of Evidence, Implementation Strategies, Practical Guidance, and Future Directions. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 1888–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatkowska, A.; White, B.; Gkikas, K.; Seenan, J.P.; MacDonald, J.; Gerasimidis, K. Partial Enteral Nutrition in the Management of Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Crohns Colitis 2025, 19, jjae177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Bager, P.; Escher, J.; Forbes, A.; Hébuterne, X.; Hvas, C.L.; Joly, F.; Klek, S.; Krznaric, Z.; Ockenga, J.; et al. ESPEN Guideline on Clinical Nutrition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 352–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godos, J.; Guglielmetti, M.; Ferraris, C.; Frias-Toral, E.; Domínguez Azpíroz, I.; Lipari, V.; Di Mauro, A.; Furnari, F.; Castellano, S.; Galvano, F.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Quality of Life in Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, F.; Magrì, S.; Cingolani, A.; Paduano, D.; Pesenti, M.; Zara, F.; Tumbarello, F.; Urru, E.; Melis, A.; Casula, L.; et al. Multidimensional Impact of Mediterranean Diet on IBD Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, K.; Güveli, H.; Erzin, Y.; Kenge, E.B.; Özlü, T. The Effect of Adherence to Mediterranean Diet on Disease Activity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 34, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migdanis, A.; Migdanis, I.; Gkogkou, N.D.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Giaginis, C.; Manouras, A.; Polyzou Konsta, M.A.; Kosti, R.I.; Oikonomou, K.A.; Argyriou, K.; et al. The Relationship of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet with Disease Activity and Quality of Life in Crohn’s Disease Patients. Medicina 2024, 60, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papada, E.; Amerikanou, C.; Forbes, A.; Kaliora, A.C. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet in Crohn’s Disease. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.; Salozzo, C.; Schwartz, S.; Hart, M.; Tuo, Y.; Wenzel, A.; Saul, S.; Strople, J.; Brown, J.; Runde, J. Following Through: The Impact of Culinary Medicine on Mediterranean Diet Uptake in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strisciuglio, C.; Cenni, S.; Serra, M.R.; Dolce, P.; Martinelli, M.; Staiano, A.; Miele, E. Effectiveness of Mediterranean Diet’s Adherence in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorindi, C.; Dinu, M.; Gavazzi, E.; Scaringi, S.; Ficari, F.; Nannoni, A.; Sofi, F.; Giudici, F. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 46, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadoni, M.; Favale, A.; Piras, R.; Demurtas, M.; Soddu, P.; Usai, A.; Ibba, I.; Fantini, M.C.; Onali, S. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Diet Quality in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Single-Center, Observational, Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altavilla, C.; Caballero-Pérez, P. An Update of the KIDMED Questionnaire, a Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in Children and Adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2543–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Amrousy, D.; Elashry, H.; Salamah, A.; Maher, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.M.; Hasan, S. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Improved Clinical Scores and Inflammatory Markers in Children with Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomized Trial. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 2075–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţincu, I.F.; Chenescu, B.T.; Duchi, L.A.; Pleșca, D.A. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Paediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders—Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, A.; Schulz, P.J. The Role of Health Literacy in Predicting Adherence to Nutritional Recommendations: A Systematic Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M.; Grysztar, M. Nutritional Behaviors, Health Literacy, and Health Locus of Control of Secondary Schoolers in Southern Poland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.K.; Sullivan, D.K.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Gajewski, B.J.; Gibbs, H.D. Nutrition Literacy Predicts Adherence to Healthy/Unhealthy Diet Patterns in Adults with a Nutrition-Related Chronic Condition. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormey, L.K.; Reich, J.; Chen, Y.S.; Singh, A.; Lipkin-Moore, Z.; Yu, A.; Weinberg, J.; Farraye, F.A.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Limited Health Literacy Is Associated With Worse Patient-Reported Outcomes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Public Health Association (EUPHA) Health Literacy Section; The EUPHA Health Services Research Section; Rademakers, J.; Okan, O. 1.K. Scientific Session: Health Literacy of Children and Adolescents across Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, ckae144.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, K.; Schumann, S.; Sander, C.; Däbritz, J.; de Laffolie, J. Health Literacy of Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and Parents of IBD Patients—Coping and Information Needs. Children 2024, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignant, S.; Pélatan, C.; Breton, E.; Cagnard, B.; Chaillou, E.; Giniès, J.-L.; Le Hénaff, G.; Ségura, J.-F.; Willot, S.; Bridoux, L.; et al. Knowledge of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: Results of a multicenter cross-sectional survey. Arch. Pediatr. 2015, 22, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mátyás, G.; Vincze, F.; Bíró, É. Egészségműveltséget Mérő Kérdőívek Validálása Hazai Felnőttmintán. Orvosi Hetil. 2021, 162, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorindi, C.; Coppolino, G.; Leone, S.; Previtali, E.; Cei, G.; Luceri, C.; Ficari, F.; Russo, E.; Giudici, F. Inadequate Food Literacy Is Related to the Worst Health Status and Limitations in Daily Life in Subjects with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 52, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnebur, L.A.; Linnebur, S.A. Self-Administered Assessment of Health Literacy in Adolescents Using the Newest Vital Sign. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, E.P.; Killingsworth, E.E. The Online Use of the Newest Vital Sign in Adolescents. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkman, E.M.; ter Brake, W.W.M.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Doggen, C.J.M. Assessment Tools for Measuring Health Literacy and Digital Health Literacy in a Hospital Setting: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Rich, B. Table1: Tables of Descriptive Statistics in HTML. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/benjaminrich/table1 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

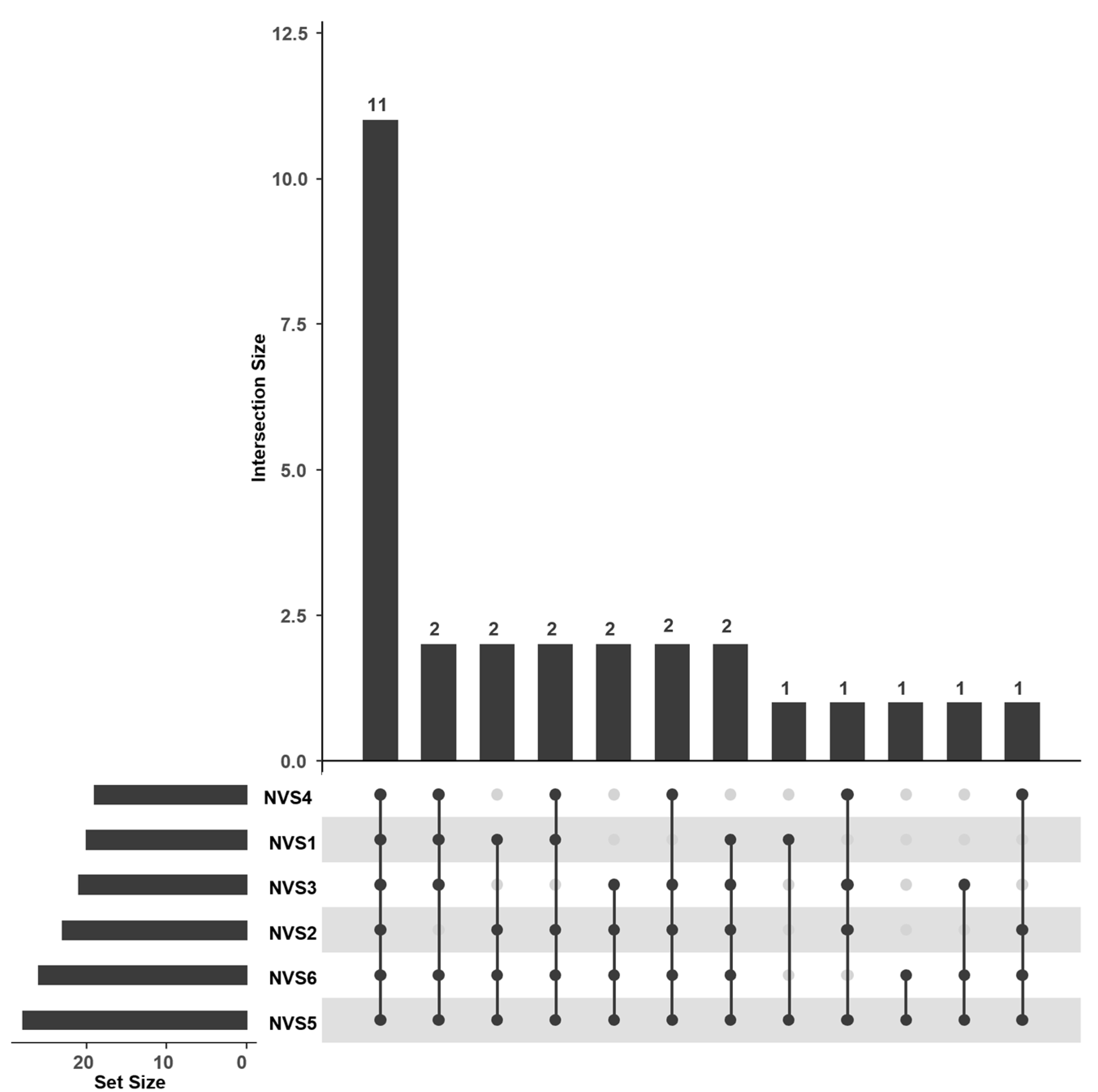

- Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: A More Scalable Alternative to Venn and Euler Diagrams for Visualizing Intersecting Sets. 2019. Available online: http://github.com/hms-dbmi/UpSetR (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; van den Brand, T. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. 2024. Available online: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Sjoberg, D.D.; Whiting, K.; Curry, M.; Lavery, J.A.; Larmarange, J. Reproducible Summary Tables with the Gtsummary Package. R J. 2021, 13, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. JPlot: Data Visualization for Statistics in Social Science. Available online: https://strengejacke.github.io/sjPlot/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Kim, D.H.; O’Connor, S.; Williams, J.; Opoku-Agyeman, W.; Chu, D.; Choi, S. The Effect of Gastrointestinal Patients’ Health Literacy Levels on Gastrointestinal Patients’ Health Outcomes. J. Hosp. Manag. Health Policy 2021, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, R.; Warsh, J.; Ketterer, T.; Hossain, J.; Sharif, I. Association between Health Literacy and Child and Adolescent Obesity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Tavakoly Sany, S.B.; Peyman, N. The Status of Health Literacy in Students Aged 6 to 18 Old Years: A Systematic Review Study. Iran. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, M.B.A.; Fujiya, R.; Kiriya, J.; Htay, Z.W.; Nakajima, K.; Fuse, R.; Wakabayashi, N.; Jimba, M. Health Literacy among Adolescents and Young Adults in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Scoping Review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control (N = 63) | Patients (N = 28) | Overall (N = 91) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 15.2 | 15.7 | 15.4 |

| SD 1 | 1.63 | 2.35 | 1.93 |

| NVS 2 score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.13 (1.58) | 4.86 (1.18) | 5.04 (1.47) |

| Median (Q1 3, Q3 4) | 6.00 (5.00, 6.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 6.00) | 6.00 (4.50, 6.00) |

| Min 5, Max 6 | 0, 6.00 | 2.00, 6.00 | 0, 6.00 |

| NVS category | |||

| high likelihood of limited HL 7 | 4 (6.3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (4.40%) |

| possibility of limited HL | 4 (6.3%) | 3 (10.71%) | 7 (7.69%) |

| adequate HL | 55 (87.3%) | 25 (89.29%) | 80 (87.91%) |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | <0.001 | ||

| Controls | – | – | |

| Patients | 7.9 | 4.3, 11 | |

| Age [Years] | 0.74 | 0.58, 0.90 | <0.001 |

| Group * Age [Years] | <0.001 | ||

| Patients * Age [Years] | −0.54 | −0.77, −0.31 |

| Characteristic | Beta | 95% CI 1 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

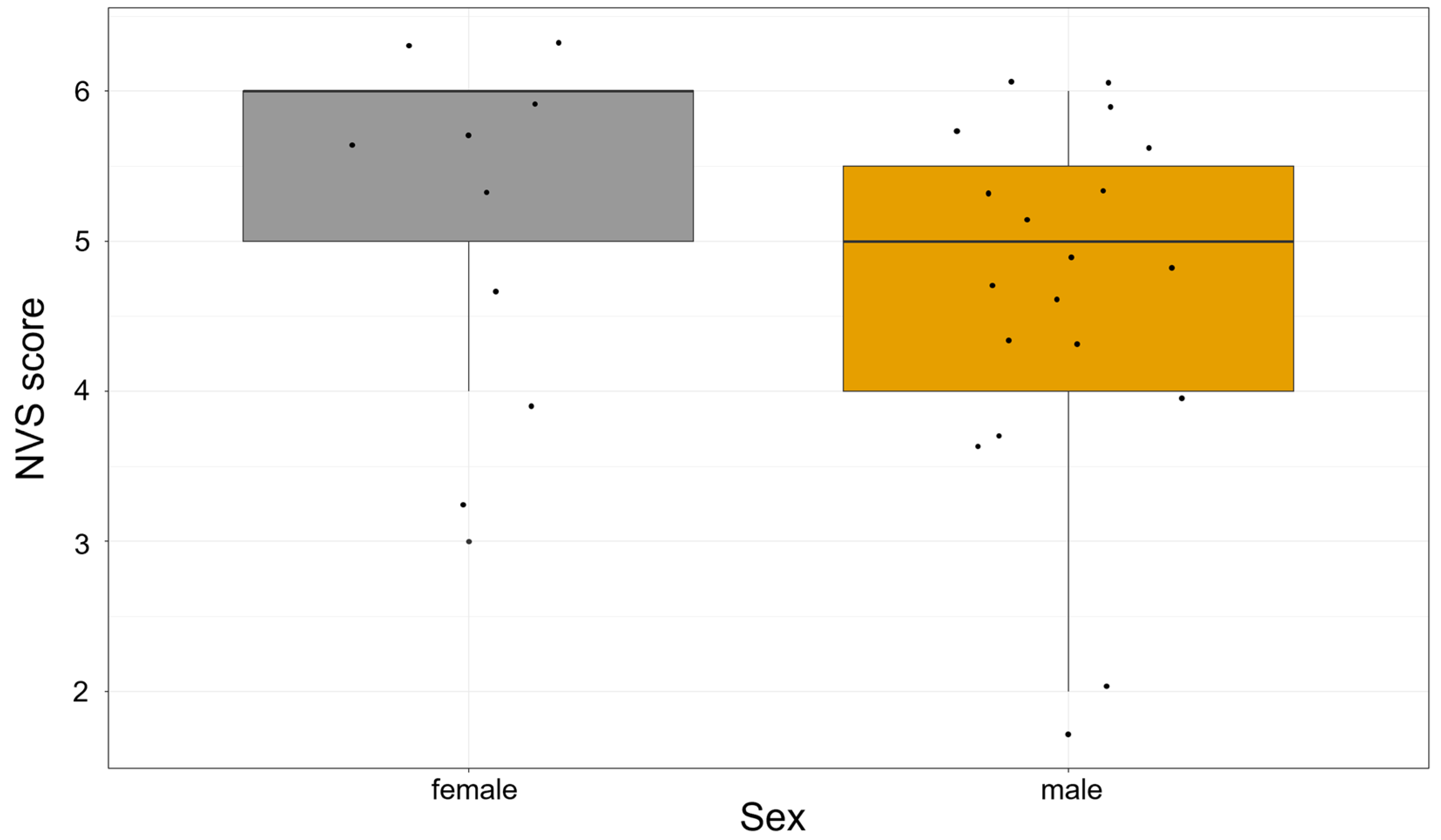

| Sex | 0.080 | ||

| Female | – | ||

| Male | −0.79 | −1.7, 0.10 | |

| Age [Years] | 0.23 | 0.06, 0.41 | <0.010 |

| Female (n = 9) | Male (n = 20) | Overall (N = 29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 14.9 | 16.0 | 15.7 |

| SD 1 | 2.71 | 2.12 | 2.35 |

| KIDMED score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.33 (1.22) | 2.35 (2.25) | 2.66 (2.02) |

| Median (Q1 2, Q3 3) | 3.00 (2.00, 4.00) | 2.00 (1.00, 4.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 4.00) |

| Min 4, Max 5 | 2.00, 5.00 | −2.00, 6.00 | −2.00, 6.00 |

| KIDMED category | |||

| poor adherence | 4 (44.44%) | 13 (65.00%) | 17 (58.62%) |

| average adherence | 5 (55.56%) | 7 (35.00%) | 12 (41.38%) |

| good adherence | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pintér, H.K.; Nagy, V.A.; Csobod, É.C.; Cseh, Á.; Béres, N.J.; Prehoda, B.; Dezsőfi-Gottl, A.; Veres, D.S.; Pálfi, E. Health Literacy and Nutrition of Adolescent Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152458

Pintér HK, Nagy VA, Csobod ÉC, Cseh Á, Béres NJ, Prehoda B, Dezsőfi-Gottl A, Veres DS, Pálfi E. Health Literacy and Nutrition of Adolescent Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152458

Chicago/Turabian StylePintér, Hajnalka Krisztina, Viola Anna Nagy, Éva Csajbókné Csobod, Áron Cseh, Nóra Judit Béres, Bence Prehoda, Antal Dezsőfi-Gottl, Dániel Sándor Veres, and Erzsébet Pálfi. 2025. "Health Literacy and Nutrition of Adolescent Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152458

APA StylePintér, H. K., Nagy, V. A., Csobod, É. C., Cseh, Á., Béres, N. J., Prehoda, B., Dezsőfi-Gottl, A., Veres, D. S., & Pálfi, E. (2025). Health Literacy and Nutrition of Adolescent Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients, 17(15), 2458. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152458