Vegetarianísh—How “Flexitarian” Eating Patterns Are Defined and Their Role in Global Food-Based Dietary Guidance

Highlights

- Flexitarian diets limit animal product consumption without eliminating them entirely.

- Flexitarian diets may be more feasible than strict vegetarian/vegan diets.

- Most food-based dietary guidance globally does not discuss flexitarian diets.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify the most used definitions of “flexitarian” dietary patterns in the scientific literature and develop draft quantitative parameters;

- Assess dietary guidance available in English to see how well guidance from the food-based dietary guidance (FBDG) of different countries aligns with most common definitions of “flexitarian” in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

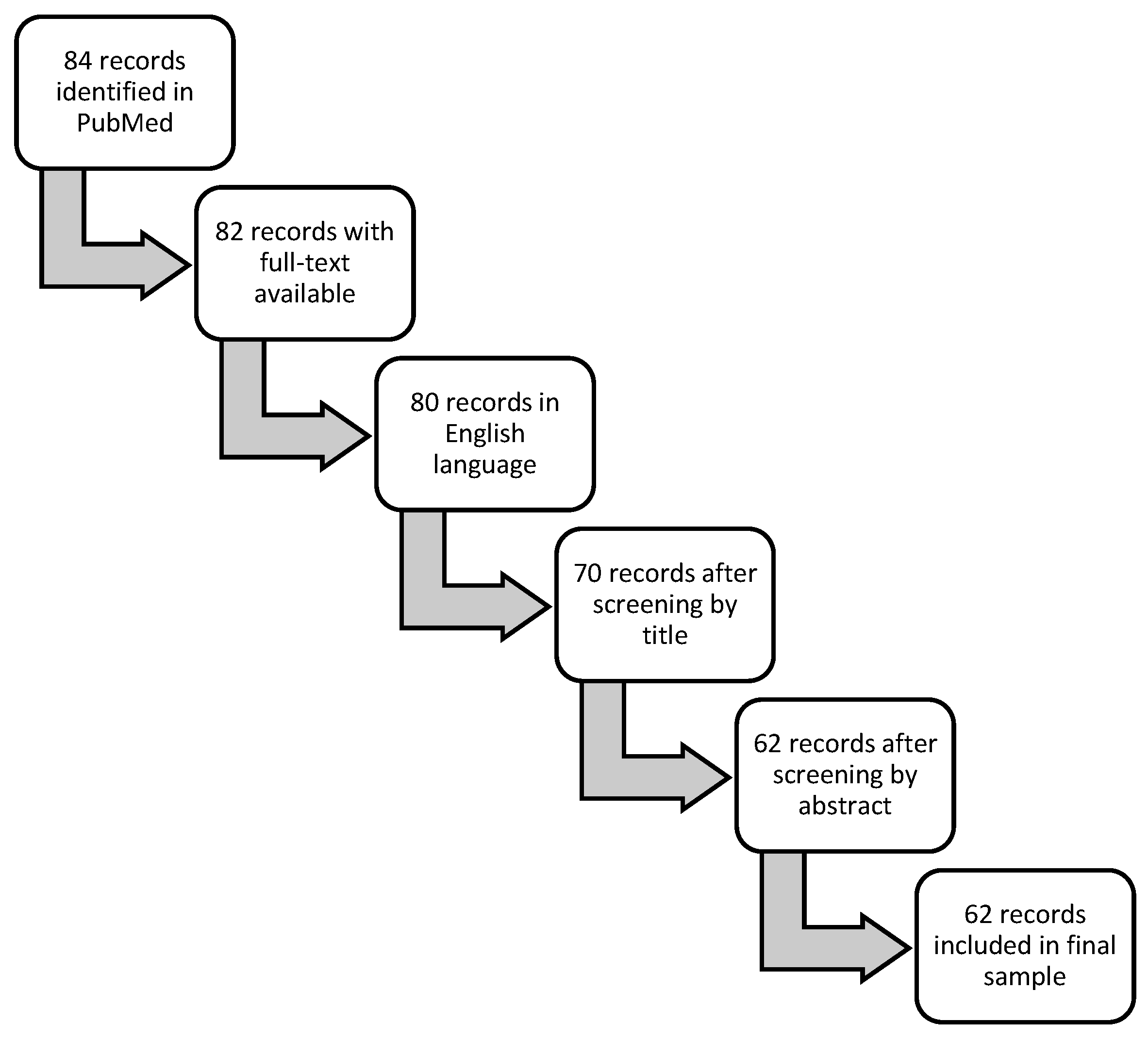

2.1. Defining Flexitarian Diets

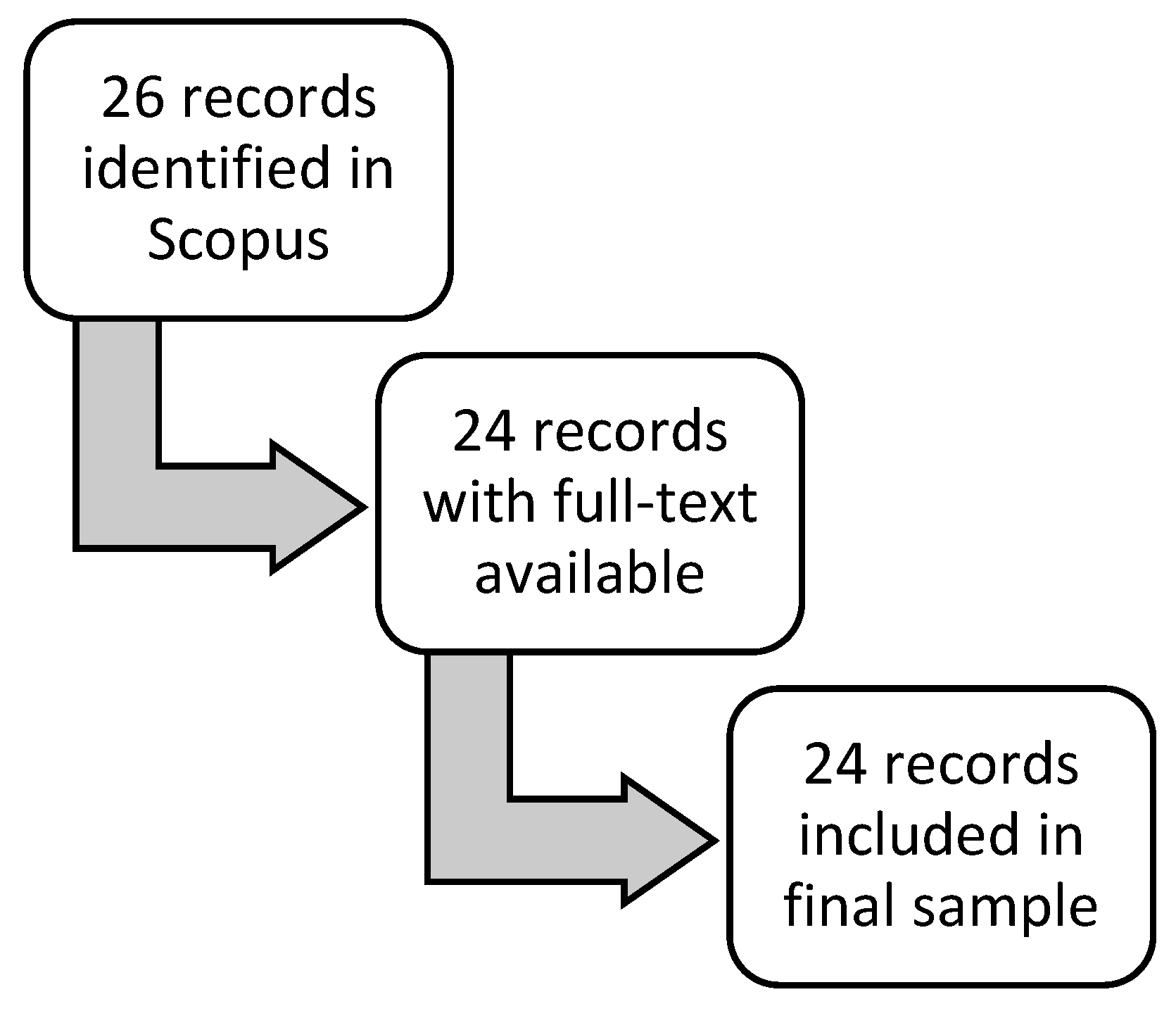

2.2. Finding FBDGs to Include

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

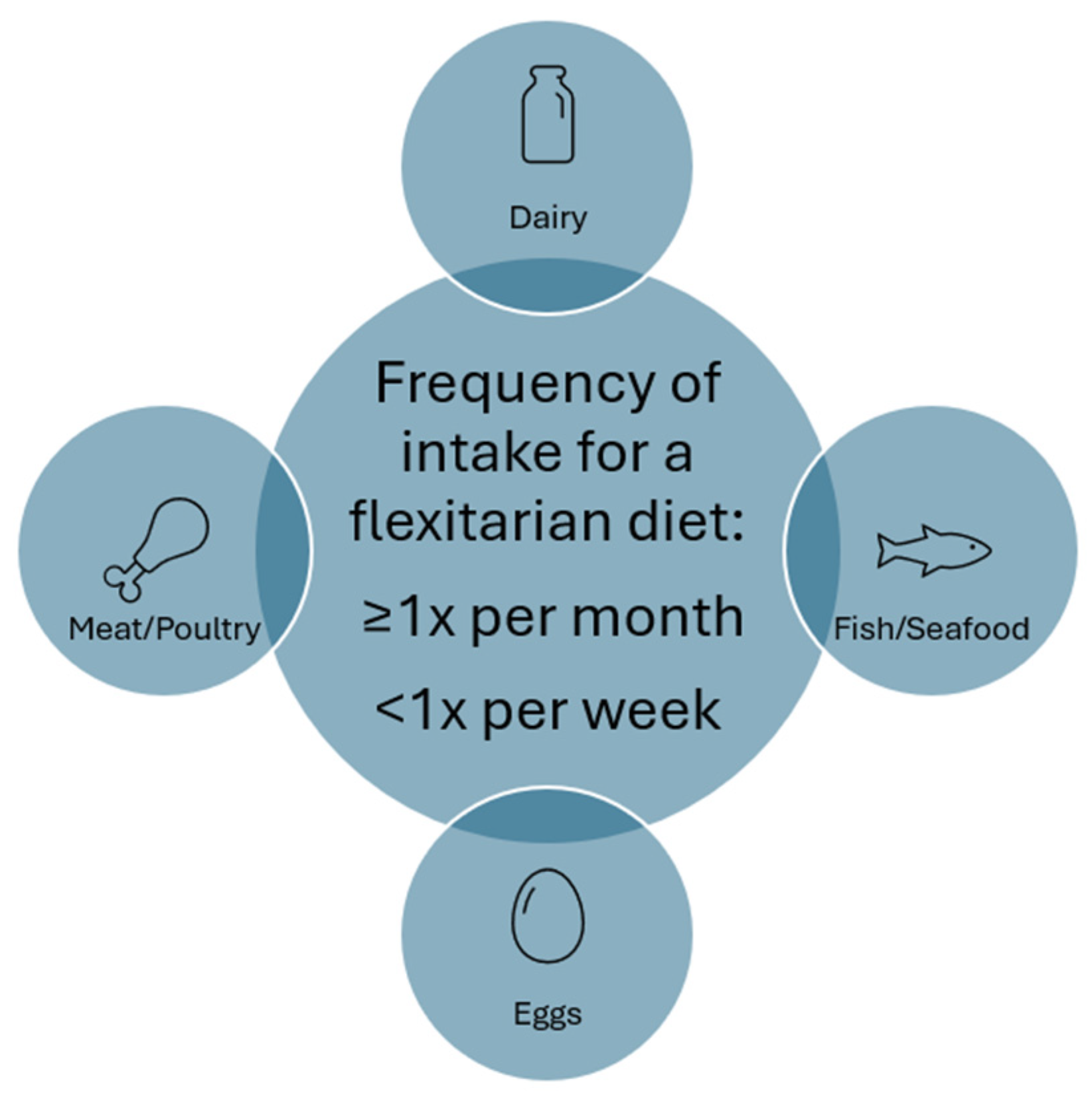

- Consume dairy products at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume eggs at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume meat and/or poultry products at least once per month but less than once per week;

- Consume fish and/or seafood at least once per month but less than once per week.

3.2. Flexitarian Diets in FBDGs

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Food Information Council. 2024 Food and Health Survey; International Food Information Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- James-Martin, G.; Baird, D.L.; Hendrie, G.A.; Bogard, J.; Anastasiou, K.; Brooker, P.G.; Wiggins, B.; Williams, G.; Herrero, M.; Lawrence, M.; et al. Environmental sustainability in national food-based dietary guidelines: A global review. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e977–e986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity: Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C.G.; Garnett, T. Plates, Pyramids, and Planets; Food Climate Research Network: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, E.J. Flexitarian diets and health: A review of the evidence-based literature. Front. Nutr. 2017, 3, 231850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.A.; White, S.K. Young adults’ experiences with flexitarianism: The 4Cs. Appetite 2021, 160, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J.C.; Alchin, C.; Anastasiou, K.; Hendrie, G.; Mellish, S.; Litchfield, C. Exploring the Intersection Between Diet and Self-Identity: A Cross-Sectional Study With Australian Adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wozniak, H.; Larpin, C.; de Mestral, C.; Guessous, I.; Reny, J.-L.; Stringhini, S. Vegetarian, pescatarian and flexitarian diets: Sociodemographic determinants and association with cardiovascular risk factors in a Swiss urban population. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashby, J.K. Fakin ‘bacon’ phony bologna and sham ham: Beef consumption has declined 15 percent over the past 20 years, according to the USDA. What’s making up to this decline? Maybe it’s and imposter. Food Process. 2005, 66, S22. [Google Scholar]

- Blatner, D.J. The Flexitarian Diet: The Mostly Vegetarian Way to Lose Weight, Be Healthier, Prevent Disease, and Add Years to Your Life; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USAC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forestell, C.A.; Spaeth, A.M.; Kane, S.A. To eat or not to eat red meat. A closer look at the relationship between restrained eating and vegetarianism in college females. Appetite 2012, 58, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/nutrition-education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Afghans; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; Ministry of Public Health (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Livestock (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan; Ministry of Education (Afghanistan): Kabul, Afghanistan, 2016.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Blomhoff, R.; Andersen, R.; Arnesen, E.K.; Christensen, J.J.; Eneroth, H.; Erkkola, M.; Gudanaviciene, I.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Høyer-Lund, A.; Lemming, E.W.; et al. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- The Public Health Division of the Pacific Community. Pacific Guidelines for Healthy Living: A Handbook for Health Professionals and Educators; Pacific Community: Nouméa, New Caledonia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M.; Quinton, S. The inter-relationship between diet, selflessness, and disordered eating in Australian women. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, J.J.; Oldmeadow, C.; Mishra, G.D.; Garg, M.L. Plant-based dietary patterns are associated with lower body weight, BMI and waist circumference in older Australian women. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihrshahi, S.; Ding, D.; Gale, J.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Banks, E.; Bauman, A.E. Vegetarian diet and all-cause mortality: Evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort—The 45 and Up Study. Prev. Med. 2017, 97, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooker, P.G.; Hendrie, G.A.; Anastasiou, K.; Woodhouse, R.; Pham, T.; Colgrave, M.L. Marketing strategies used for alternative protein products sold in Australian supermarkets in 2014, 2017, and 2021. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1087194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtain, F.; Grafenauer, S. Plant-based meat substitutes in the flexitarian age: An audit of products on supermarket shelves. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakin, B.C.; Ching, A.E.; Teperman, E.; Klebl, C.; Moshel, M.; Bastian, B. Prescribing vegetarian or flexitarian diets leads to sustained reduction in meat intake. Appetite 2021, 164, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baines, S.; Powers, J.; Brown, W.J. How does the health and well-being of young Australian vegetarian and semi-vegetarian women compare with non-vegetarians? Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. From meatless Mondays to meatless Sundays: Motivations for meat reduction among vegetarians and semi-vegetarians who mildly or significantly reduce their meat intake. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Backer, C.J.; Hudders, L. Meat morals: Relationship between meat consumption consumer attitudes towards human and animal welfare and moral behavior. Meat Sci. 2015, 99, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groeve, B.; Hudders, L.; Bleys, B. Moral rebels and dietary deviants: How moral minority stereotypes predict the social attractiveness of veg*ns. Appetite 2021, 164, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, J.B.; Silva, Y.d.O.; Santos, S.S.; Dionísio, A.P.; de Sousa, P.H.M.; Garruti, D.d.S. Plant-based gastronomic products based on freeze-dried cashew fiber. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, U.M.; Gibson, R.S. Dietary intakes of adolescent females consuming vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous diets. J. Adolesc. Health 1996, 18, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švarc, P.L.; Jensen, M.B.; Langwagen, M.; Poulsen, A.; Trolle, E.; Jakobsen, J. Nutrient content in plant-based protein products intended for food composition databases. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 106, 104332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Reay, D.S.; Higgins, P. Potential of Meat Substitutes for Climate Change Mitigation and Improved Human Health in High-Income Markets. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaapila, A.; Michel, F.; Jouppila, K.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Piironen, V. Millennials’ Consumption of and Attitudes toward Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives by Consumer Segment in Finland. Foods 2022, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Päivärinta, E.; Itkonen, S.T.; Pellinen, T.; Lehtovirta, M.; Erkkola, M.; Pajari, A.-M. Replacing animal-based proteins with plant-based proteins changes the composition of a whole Nordic diet—A randomised clinical trial in healthy Finnish adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torfadottir, J.E.; Aspelund, T. Flexitarian diet to the rescue. Laeknabladid 2019, 105, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, N.; Huneau, J.-F.; Mariotti, F. Self-declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Eve, A.; Granda, P.; Legay, G.; Cuvelier, G.; Delarue, J. Consumer acceptance and sensory drivers of liking for high plant protein snacks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 3983–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gousset, C.; Gregorio, E.; Marais, B.; Rusalen, A.; Chriki, S.; Hocquette, J.-F.; Ellies-Oury, M.-P. Perception of cultured “meat” by French consumers according to their diet. Livest. Sci. 2022, 260, 104909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessler-Kaufmann, J.B.; Meule, A.; Holzapfel, C.; Brandl, B.; Greetfeld, M.; Skurk, T.; Schlegl, S.; Hauner, H.; Voderholzer, U. Orthorexic tendencies moderate the relationship between semi-vegetarianism and depressive symptoms. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, A.; Mueller, M.; Schneider, I.; Hahn, A. Application of a modified healthy eating index (HEI-Flex) to compare the diet quality of flexitarians, vegans and omnivores in Germany. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seel, W.; Reiners, S.; Kipp, K.; Simon, M.C.; Dawczynski, C. Role of Dietary Fiber and Energy Intake on Gut Microbiome in Vegans, Vegetarians, and Flexitarians in Comparison to Omnivores-Insights from the Nutritional Evaluation (NuEva) Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, M.A. What makes a plant-based diet? a review of current concepts and proposal for a standardized plant-based dietary intervention checklist. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 76, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bánáti, D. Flexitarianism—The sustainable food consumption? Élelmiszervizsgálati Közlemények 2022, 68, 4075–4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, J.; Vasas, D.; Ahmed, M. Comparative Analysis of Flexitarian, Vegetarian and Vegan Diets: A Review. Élelmiszervizsgálati Közlemények 2023, 69, 4382–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.A.; Meyer, R.; Donovan, S.M.; Goulet, O.; Haines, J.; Kok, F.J.; Van’t Veer, P. Perspective: Striking a Balance between Planetary and Human Health-Is There a Path Forward? Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 355–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagevos, H. Finding flexitarians: Current studies on meat eaters and meat reducers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: A review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestell, C.A. Flexitarian Diet and Weight Control: Healthy or Risky Eating Behavior? Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukid, F.; Rosell, C.M.; Rosene, S.; Bover-Cid, S.; Castellari, M. Non-animal proteins as cutting-edge ingredients to reformulate animal-free foodstuffs: Present status and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6390–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, F. Meat as a Pharmakon: An Exploration of the Biosocial Complexities of Meat Consumption. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 87, 409–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, M.; Swanepoel, A.C. The effect of plant-based diets on thrombotic risk factors. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2021, 131, 16123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouritsen, O.G.; Styrbæk, K. Design and ‘umamification’ of vegetable dishes for sustainable eating. Int. J. Food Des. 2020, 5, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiel, U.; Landau, N.; Fuhrer, A.E.; Shalem, T.; Goldman, M. The Knowledge and Attitudes of Pediatricians in Israel Towards Vegetarianism. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, P.; Rossano, R.; Larocca, M.; Trotta, V.; Mennella, I.; Vitaglione, P.; Ettorre, M.; Graverini, A.; De Santis, A.; Di Monte, E.; et al. Anti-inflammatory nutritional intervention in patients with relapsing-remitting and primary-progressive multiple sclerosis: A pilot study. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, M.; Marescotti, M.E.; Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A. Validation of the Dietarian Identity Questionnaire (DIQ): A case study in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliceri, D.; Spinelli, S.; Dinnella, C.; Prescott, J.; Monteleone, E. The influence of psychological traits, beliefs and taste responsiveness on implicit attitudes toward plant- and animal-based dishes among vegetarians, flexitarians and omnivores. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, M.; Abe, T.; Tsuda, H.; Sugawara, T.; Tsuda, S.; Tozawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Imai, H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekema, R.; Tyszler, M.; van ‘t Veer, P.; Kok, F.J.; Martin, A.; Lluch, A.; Blonk, H.T.J. Future-proof and sustainable healthy diets based on current eating patterns in the Netherlands. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Meer, M.; Fischer, A.R.; Onwezen, M.C. Same strategies–different categories: An explorative card-sort study of plant-based proteins comparing omnivores, flexitarians, vegetarians and vegans. Appetite 2023, 180, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, B.; Jouppila, K.; Sandell, M.; Knaapila, A. No meat, lab meat, or half meat? Dutch and Finnish consumers’ attitudes toward meat substitutes, cultured meat, and hybrid meat products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 108, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaren, O.; Mackay, L.; Schofield, G.; Zinn, C. Novel Nutrition Profiling of New Zealanders’ Varied Eating Patterns. Nutrients 2017, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, J.A. Motivations, barriers, and strategies for meat reduction at different family lifecycle stages. Appetite 2020, 150, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillies, N.A.; Worthington, A.; Li, L.; Conner, T.S.; Bermingham, E.N.; Knowles, S.O.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Hannaford, R.; Braakhuis, A. Adherence and eating experiences differ between participants following a flexitarian diet including red meat or a vegetarian diet including plant-based meat alternatives: Findings from a 10-week randomised dietary intervention trial. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1174726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Realini, C.E.; Driver, T.; Zhang, R.; Guenther, M.; Duff, S.; Craigie, C.R.; Saunders, C.; Farouk, M.M. Survey of New Zealand consumer attitudes to consumption of meat and meat alternatives. Meat Sci. 2023, 203, 109232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famodu, A.A.; Osilesi, O.; Makinde, Y.O.; Osonuga, O.A. Blood pressure and blood lipid levels among vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and non-vegetarian native Africans. Clin. Biochem. 1998, 31, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Bugge, A.B.; Morseth, M.S.; Pedersen, J.T.; Henjum, S. Dietary Habits and Self-Reported Health Measures Among Norwegian Adults Adhering to Plant-Based Diets. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 813482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwaśniewska, M.; Pikala, M.; Grygorczuk, O.; Waśkiewicz, A.; Stepaniak, U.; Pająk, A.; Kozakiewicz, K.; Nadrowski, P.; Zdrojewski, T.; Puch-Walczak, A.; et al. Dietary Antioxidants, Quality of Nutrition and Cardiovascular Characteristics among Omnivores, Flexitarians and Vegetarians in Poland-The Results of Multicenter National Representative Survey WOBASZ. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguerol, A.T.; Pagán, M.J.; García-Segovia, P.; Varela, P. Green or clean? Perception of clean label plant-based products by omnivorous, vegan, vegetarian and flexitarian consumers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spendrup, S.; Hovmalm, H.P. Consumer attitudes and beliefs towards plant-based food in different degrees of processing—The case of Sweden. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 102, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Dietary change scenarios and implications for environmental, nutrition, human health and economic dimensions of food sustainability. Nutrients 2019, 11, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, C.F.; Tini, G.; Vassallo, I.; Godin, J.P.; Su, M.; Jia, W.; Beaumont, M.; Moco, S.; Martin, F.P. Vegan and Animal Meal Composition and Timing Influence Glucose and Lipid Related Postprandial Metabolic Profiles. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1800568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northstone, K.; Emmett, P.M. Dietary patterns of men in ALSPAC: Associations with socio-demographic and lifestyle characteristics, nutrient intake and comparison with women’s dietary patterns. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capper, J. A sustainable future isn’t vegan, it’s flexitarian. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Buckland, N.J. Perceptions about meat reducers: Results from two UK studies exploring personality impressions and perceived group membership. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio-Mateas, M.A.; Bester, A.; Klimenko, N. Impact of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives on the Gut Microbiota of Consumers: A Real-World Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forestell, C.A.; Nezlek, J.B. Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2018, 57, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, W.J.; McGrievy, M.E.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M. Dietary adherence and acceptability of five different diets, including vegan and vegetarian diets, for weight loss: The New DIETs study. Eat. Behav. 2015, 19, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Davidson, C.R.; Wilcox, S. Does the type of weight loss diet affect who participates in a behavioral weight loss intervention? A comparison of participants for a plant-based diet versus a standard diet trial. Appetite 2014, 73, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Wirth, M.D.; Shivappa, N.; Wingard, E.E.; Fayad, R.; Wilcox, S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Hébert, J.R. Randomization to plant-based dietary approaches leads to larger short-term improvements in Dietary Inflammatory Index scores and macronutrient intake compared with diets that contain meat. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotillard, A.; Cartier-Meheust, A.; Litwin, N.S.; Chaumont, S.; Saccareau, M.; Lejzerowicz, F.; Tap, J.; Koutnikova, H.; Lopez, D.G.; McDonald, D. A posteriori dietary patterns better explain variations of the gut microbiome than individual markers in the American Gut Project. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.C. Plant-Based Diets: A Primer for School Nurses. NASN Sch. Nurse 2021, 36, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Guinard, J.X. The flexitarian flip™: Testing the modalities of flavor as sensory strategies to accomplish the shift from meat-centered to vegetable-forward mixed dishes. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tso, R.; Forde, C.G. Unintended consequences: Nutritional impact and potential pitfalls of switching from animal-to plant-based foods. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.A.; Malone, T.; McFadden, B.R. Beverage milk consumption patterns in the United States: Who is substituting from dairy to plant-based beverages? J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11209–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Kurzer, A.; Cienfuegos, C.; Guinard, J.-X. Student consumer acceptance of plant-forward burrito bowls in which two-thirds of the meat has been replaced with legumes and vegetables: The Flexitarian Flip™ in university dining venues. Appetite 2018, 131, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L., III; Welland, D. Intake of 100% Fruit Juice Is Associated with Improved Diet Quality of Adults: NHANES 2013–2016 Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, F.L.; Lloren, J.I.C.; Haddad, E.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Knutsen, S.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Plasma, Urine, and Adipose Tissue Biomarkers of Dietary Intake Differ Between Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Diet Groups in the Adventist Health Study-2. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penniecook-Sawyers, J.A.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Beeson, L.; Knutsen, S.; Herring, P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian dietary patterns and the risk of breast cancer in a low-risk population. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Sabaté, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian dietary patterns are associated with a lower risk of metabolic syndrome: The adventist health study 2. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Fraser, G. Vegetarian diets and the incidence of cancer in a low-risk population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y.; Knutsen, S.F.; Knutsen, R.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Fan, J.; Beeson, W.L.; Sabate, J.; Hadley, D.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Penniecook, J.; et al. Are strict vegetarians protected against prostate cancer? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Butler, T.; Yan, R.; Fraser, G.E. Type of vegetarian diet, body weight, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Stewart, K.; Oda, K.; Batech, M.; Herring, R.P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkholder-Cooley, N.; Rajaram, S.; Haddad, E.; Fraser, G.E.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K. Comparison of polyphenol intakes according to distinct dietary patterns and food sources in the Adventist Health Study-2 cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.; Rowe, S.; Bonnell, C.; Dalton, P. Consumer acceptance of plant-forward recipes in a natural consumption setting. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiloglou, M.F.; Pascual, P.E.; Scuccimarra, E.A.; Plestina, R.; Mainardi, F.; Mak, T.N.; Ronga, F.; Drewnowski, A. Assessing the Quality of Simulated Food Patterns with Reduced Animal Protein Using Meal Data from NHANES 2017–2018. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miassi, Y.E.; Dossa, F.K.; Zannou, O.; Akdemir, Ş.; Koca, I.; Galanakis, C.M.; Alamri, A.S. Socio-cultural and economic factors affecting the choice of food diet in West Africa: A two-stage Heckman approach. Discov. Food 2022, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phnom Penh Minister of Health. Development of Recommended Dietary Allowance and Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for School-Aged Children in Cambodia; Phnom Penh Minister of Health: Phnom Penh, CambodiaT, 2017.

- National Food and Nutrition Centre. Food & Health Guidelines for Fiji; National Food and Nutrition Centre: Suva, FijiThi, 2013.

- Ministry of Health Nutrition Division. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Sri Lankans: Practitioner’s Handbook; Ministry of Health Nutrition Division: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2021.

- García, E.L.; Lesmes, I.B.; Perales, A.D.; Moreno-Arri-bas, V.; Portillo Baquedano, M.P.; Rivas Velasco, A.M.; Fresán Salvo, U.; Tejedor Romero, L.; Ortega Porcel, F.B.; Aznar Laín, S.; et al. Report of the Scientific Committee of the Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) on sustainable dietary and physical activity recommendations for the Spanish population. Rev. Com. Científico AESAN 2022, 36, 11–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Dietary Society (DGE). Eat and Drink Well—Recommendations of the German Nutrition Society (DGE); German Dietary Society: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- General Directorate of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Saudis: The Healthy Food Palm; General Directorate of Nutrition: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2012.

- Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Providing the Scientific Evidence for Healthier Australian Diets; Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Superior Health Council. Dietary Guidelines for the Belgian Adult Population; Superior Health Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Center of Public Health Protection. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Adults in Bulgaria; National Center of Public Health Protection: Sofia, BulgariaT, 2006.

- Barbados Mnistry of Health. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Barbados; National Nutrition Centre, Ministry of Health Ladymeade Gardens: Bridgetown, Barbados, 2017.

- Public Health England. A Quick Guide to the Government’s Healthy Eating Recommendations; Office for Health Improvement and Disparities: London, UK, 2016.

- Public Health Department, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affaires, World Health Organization. Healthy Eating—The Main Key to Health (FBDG-for Georgia); Public Health Department, Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affaires, World Health Organization: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2005.

- Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Ghana: National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—2023; University of Ghana School of Public Health: Accra, Ghana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy Ireland—Department of Health. Healthy Food for Life—The Healthy Eating Guidelines 2015–2016; Healthy Ireland—Department of Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2015.

- The Israeli Ministry of Health, Nutrition Department. Nutritional Recommendations. 2019. Available online: https://efsharibari.health.gov.il/media/1906/nutritional-recommendations-2020.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- World Health Organization; Sultanate of Oman. The Omani Guide for Healthy Eating; Department of Nutrition, Ministry of Health Oman: Muscat, Oman, 2024.

- Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top; Food Safety and Consumer Affairs Bureau, Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Tokyo, Japan, 2010.

- Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health. National Guidelines for Healthy Diets and Physical Activity; Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017.

- The American University of Beirut. Lebanon: Food-Based Dietary Guidelines; The Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences; American University of Beirut: Beirut, Lebanon, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands. Dutch Dietary Guidelines 2015; Health Council of The Netherlands: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020.

- National Council for Nutrition. The Norwegian Dietary Guidelines; Norwegian Directorate of Health: Oslo, Norway, 2012.

- Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (FNRI-DOST). Nutritional Guidelines for Filipinos (NGF); Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (FNRI-DOST): Manila, Philippines, 2012.

- The Supreme Council of Health-State of Qatar. Qatar Dietary Guidelines; The Supreme Council of Health-State of Qatar: Doha, Qatar, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Healthy Eating; Government of Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, German Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection: Berlin, Germany, 2016.

- National Food Agency. The Swedish Dietary Guidelines: Find Your Way to Eat Greener, Not Too Much and Be Active; National Food Agency: Uppsala, Sweden, 2015.

- Ministry of Agriculture. Zambia Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Technical Recommendations; Ministry of Agriculture: Lusaka, Zambia, 2021.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—India. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/india/en/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Department of Public Health Tirana. Recommendations on Healthy Nutrition in Albania; Department of Public Health Tirana: Tirana, Albania, 2008.

- Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM). Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh; Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Federal Government of Ethiopia. Ethiopia: Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—2022; Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Ministry of Health, Federal Government of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022.

- Ministry of Health Jamaica. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Jamaica; Ministry of Health Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica, 2015.

- Health Promotion Unit-Ministry of Health, Social Service, Community Development, Culture and Gender Affairs. Food Based Dietary Guidelines—St. Kitts & Nevis; Ministry of Health, Social Services, Community Development, Culture and Gender Affairs: Basseterre, St. Kitts & Nevis, 2010.

- Ministry of health, Wellness and the Environment. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Ministry of Health, Wellness and the Environment: Kingstown, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, 2021.

- Department of Health; Nutrition Society of South Africa. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa; Department of Health: Pretoria, Gauteng; Nutrition Society of South Africa: Brits, Gauteng, 2013.

- Nutrition Unit of the Ministry of Health. The Seychelles Dietary Guidelines; Nutrition Unit of the Ministry of Health: Victoria, Seychelles, 2006.

- Ministry of Health-Belize. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Belize; Ministry of Health Belize: Belmopan, Belize, 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7cacbe3e-be9d-4b33-8153-62a07ff21206/content (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- National Institute of Nutrition, India. Dietary Guidelines for Indians; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Turkey. Dietary Guidelines for Turkey: Adequate and Balanced Nutrition; Hacettepe University Department of Nutrition and Dietetics: Ankara, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, S.; Guest, N.S.; Landry, M.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Pawlak, R.; Rozga, M. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns for Adults: A Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Neu, P.; Berg, P.; Harding, J.; McKenzie, S.; Ramsing, R. The origins and growth of the Meatless Monday movement. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1283239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.M.; Taillie, L.S.; Jaacks, L.M. How Americans eat red and processed meat: An analysis of the contribution of thirteen different food groups. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, J.M.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Slavin, J.L. Dairy foods: Current evidence of their effects on bone, cardiometabolic, cognitive, and digestive health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salter, A.M. Insect Protein: A Sustainable and Healthy Alternative to Animal Protein? J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 545–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiking, H.; de Boer, J. Protein and sustainability—The potential of insects. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Álvarez-Sánchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Canada. Canada’s Dietary Guidelines; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Lavigne, S.E.; Lengyel, C. A new evolution of Canada’s Food Guide. Can. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 53, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil, Secretariat of Health Care, Primary Health Care Department. Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population; Ministry of Health of Brazil: Brasília, Brazil; São Paulo, Brazil, 2015. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/dietary_guidelines_brazilian_population.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

| Geographical Location of Study [Citation] | Term(s) Used for “Flexitarian” Dietary Patterns | How Dietary Pattern Low in Animal Products Are Described/Defined |

|---|---|---|

| Australia [18] | Semi-vegetarian | “Individuals who follow a vegetarian diet but occasionally eat meat or poultry” |

| Australia [19] | Semi-vegetarian | “very minimal and/or infrequent consumption of meat.” |

| Australia [20] | Semi-vegetarian | “Eat meat ≤ 1 timeweek” |

| Australia [21] | Flexitarian | “those who occasionally include conventional meat” |

| Australia [22] | Flexitarian | “Eating less meat” |

| Australia [23] | Flexitarian | “…where meat consumption is reduced in some significant way without being eliminated completely.” |

| Australia [8] |

| “…only eat meat on a few days per week or special occasions” and “people who avoid 1 type of meat product but not another (e.g., pescatarian)” |

| Australia [24] | Semi-vegetarian | Defined as semi-vegetarians “if they excluded red meat” |

| Belgium [25] | Semi-vegetarian | “people who reduce, but not entirely stop, their meat intake, lean mostly towards health motives.” -Semi-vegetarians: “strongly reduced meat intake” -light semi-vegetarians: “avoid meat one or two days a week” |

| Belgium [26] | Flexitarian | Flexitarians are…”a growing group of consumers that reduce, but do not ban, meat from their diets.” “Consciously reducing meat intake, but eating meat now and then.” |

| Belgium [27] |

| “Flexitarian: ‘people who consciously reduce their meat intake, but eat meat now and then’“ “Semi-vegetarians: …excluded certain types of meat (red meat, poultry or fish and seafood) from their diet” |

| Belgium [28] |

| “Individuals who have low or occasional meat intake” |

| Brazil [29] | Flexitarian | “maintain a vegetarian diet most of the time but still eat meat” “avoid the consumption of animal products…not totally eliminating them” |

| Canada [30] | Semi-vegetarian | “…consumed red meat less than once a month, but included poultry and/or fish in their diets more than once a month.” |

| Denmark [31] | Flexitarian | “consumes vegetarian food a few days per week” |

| Europe/USA/Australia/New Zealand/South Africa [32] | Flexitarian | “primarily vegetarian but occasionally eating meat and fish” |

| Finland [33] | Flexitarian | “abstains from meat occasionally without abandoning meat totally” “a middle category between consumers who regularly eat meat and those who fully abstain from it” |

| Finland [34] | Flexitarian | Planetary Health Diet: “A flexitarian diet consisting mainly of plant-based foods and containing only small amounts of animal-based foods. It aims to more than double the consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts, and more than half of the global consumption of red meat and added sugars by 2050.” |

| Finland [35] | Flexitarian | “The main protein sources are as follows per weekly dose: -100 g of red meat -200 g of poultry meat -200 g fish -350 g nuts, -90 g eggs -525 g beans/legumes” |

| France [36] | Flexitarian | Flexitarian: “limiting meat consumption to a minimum” “Pro-flexitarians”: “I am considering eating meat and fish only very rarely (no more than once a week) and were not flexitarians or vegetarians.” |

| France [37] | Flexitarian | A consumer study was the result of this study—participants were asked: “which of the following suits you?” 1. I like meat a lot and consume a lot, I can hardly imagine a meal without meat.” = omnivores 2. “I like meat, I consume regularly.” = omnivores 3. I prefer fish to meat, but I eat meat when the opportunity arises.” = omnivores 4. “I try to limit my consumption of meat/fish but I can make exceptions (at the restaurant, at friends’ place)” = flexitarian 5. “I do not eat meat or fish.” = vegetarian 6. “I do not eat meat at all, but fish can be eaten occasionally.” = strong vegetarian trend 7. “I do not eat meat, fish, eggs, or dairy.” = vegan |

| France [38] | Flexitarian | “diet that limits meat consumption for reasons other than financial. The flexitarian seeks a balanced and varied diet. They therefore also consume animal products” |

| Germany [39] | Semi-vegetarian | In the study, semi-vegetarians were defined by “those who negated [these] statements but endorsed the statement ‘I mostly eat vegetarian (no red meat but sometimes poultry and/or fish)’“ |

| Germany [40] | Flexitarian | “…broadly characterized by a primarily vegetarian diet pattern with occasional meat or fish consumption. However, a generally accepted definition of flexitarianism does not currently exist.” |

| Germany [41] | Flexitarian | no description provided |

| Global [42] | Semi-vegetarian | Review; ~20% of studies allowed participants a semi-vegetarian diet including fish and meat products |

| Global [43] |

| “actively reduce or fully exclude at least some animal products” “cutting back on meat but are not avoiding meat completely” “individuals reporting ‘a lot less’ or ‘slightly less’ consumption v. three years ago for one or more of the four meat types” “do not exceed the maximum meat intake officially recommended by national dietary guidelines” “aim to reduce animal products…but do not strictly exclude any food group” “choose less or without meat meals if they were available” “a predominantly plant-based diet complemented with modest amounts of animal foods” |

| Global [44] |

| “choose mainly plant-based food products…also eat meat and other animal-based products” |

| Global [45] | Flexitarian | “omnivorous diets that incorporate high amounts of plant-sourced foods; moderate amounts of poultry, dairy and fish; and low amounts of red meat, highly processed foods, and added sugar” |

| Global [6] |

| “…reflects consumers who are ‘meat-reducers,’ eating meat within meals on some but not every day of the week.” -Variability in review studies defined; some restricted intake of red meat, some restricted fish -Adventist health study defined as those consuming dairy products and/or eggs and meat (red meat and poultry1 time/month and < time/week) -”…containing moderate levels of animal products, though [it] was not specified what ‘moderate’ was.” -”…eating red meat, poultry, or fish no more than 1 time/week” -”semi-vegetarian if [they] excluded red meat from [their] diet but ate other meats.” |

| Global [46] | Flexitarian | “Limit[ing] meat consumption by abstaining from eating meat occasionally.” “…a consumption pattern in which meat is eaten occasionally without avoiding it completely.” |

| Global [47] |

| “…described as a primarily vegetarian diet but allows some animal food consumption, however, the amount and type of animal foods varies, from a specified amount of animal food per month to exclusion of red meat only but inclusion of poultry, fish and other animal foods.” -Includes fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts, seeds, beans, pulses and fish, dairy, eggs, and meat (on some but not all days of the week). Excludes restrictions on meat. |

| Global [48] | Flexitarian | “…those who eat a mostly vegetarian diet but occasionally eat meat.” |

| Global [49] |

| “The diet consists of the reduction of the consumption of animal products in favor of those plant-based products…” |

| Global [50] |

| “As a sort of semi-vegetarianism, it consists of the eating of a mostly plant-based diet with the occasional inclusion of meat (for instance, during weekends).” |

| Global [51] |

| “meat consumption once or twice a week.” “…are mainly plant-based but occasionally include meat, dairy, and eggs and focus on variety while attempting to minimize animal product consumption.” |

| Global [52] | Flexitarian | No description provided |

| Israel [53] | Semi-vegetarian | “Mainly but not completely vegetarian; the consumption of meat or fish less than once weekly and more than once monthly” |

| Italy [54] | Semi-vegetarian | “…In general, the diet was based mainly on the principles of a Mediterranean diet but with some important modifications: it was semi-vegetarian, with a preference for fish instead of meat, and lower gluten content, than the usual Mediterranean diet.” |

| Italy [55] |

| “an individual who abstains from eating meat regularly” “exclude at least one type of meat, but not all meats, from their diets” |

| Italy [56] | Flexitarian | “those who consciously consume a limited quantity of either all types or specific types of meat” |

| Japan [57] | Semi-vegetarian | -Eggs and milk were used. In other words, our diet was a lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet. -Miso (fermented bean paste) soup, vegetables, fruits, legumes, potatoes, pickled vegetables, and plain yoghurt were served daily. -Fish was served once a week and meat once every 2 weeks, both at about a half the average amount. Patients were provided with several different 4-wk menus on a rotational basis. |

| Netherlands [58] | Semi-vegetarian | “…a flexitarian diet with 35 g meat/day” |

| Netherlands [59] | Flexitarian | “Consumers who deliberately reduce meat consumption in frequency.” |

| Netherlands; Finland [60] | Flexitarian | “abstain from eating meat in certain situations due to varying reasons” |

| New Zealand [7] |

| “An individual who reduces their consumption of meat and can include those who avoid meat one or two days a week to those who only eat meat on occasion” |

| New Zealand [61] | Flexitarian | “This group was based on the irregular or non-consumption of white, red and processed meat and was designed to include as many meat restricting groups as possible, such as; ovo-vegetarians, vegetarians, and vegans, and both strict and flexible followers.” |

| New Zealand [62] |

| “is an individual who limits his or her meat intake yet still includes meat in his or her diet.” |

| New Zealand [63] |

| “vegetarian diets with moderate amounts of red meat” |

| New Zealand [64] |

| no description provided |

| Nigeria [65] | Semi-vegetarian | “semi-vegetarians consuming one to three servings of flesh food per week.” |

| Norway [66] |

| “trying to reduce their intake of animal source food when convenient” “occasionally eat meat” |

| Poland [67] |

| “eating dairy products on regular basis but red meat or poultry at a frequency of at least 1 time per month but less than 1 time per week” |

| Spain/Europe/Latin America [68] | Flexitarian | “[Flexitarians are] semi-vegetarian because do not exclude meat products (red meat or other meats) but limit their consumption.” |

| Sweden [69] | Flexitarian | “meat reducers” |

| Switzerland [70] |

| “…flexitarian or semi-vegetarian diet, is a predominantly plant-based diet with the occasional inclusion of meat or fish.” |

| Switzerland [9] |

| Participants in this study were considered flexitarians when they included eggs and dairy products in their daily diet and red meat or poultry at a frequency of ≥1 time/month but ≤1 time/week |

| Switzerland [71] |

| “Mediterranean, Nordic, and flexitarian (semi-vegetarian) diets are omnivorous diets with an emphasis on plant-based foods…” |

| UK [72] | Semi-vegetarian | “…was characterized by high intakes of meat substitutes, pulses, nuts, and fish.” |

| UK [73] | Flexitarian | “The definition of a flexitarian diet is variable-it can involve anything from a conscious decision not to eat meat at every meal, to giving up meat once per day per week or eating a primarily vegetarian diet, augmented with the occasional meat burger. Ironically, this means that, at present, the majority of people could be classed as flexitarian, even if they do not necessarily use or welcome that label.” |

| UK [74] |

| “largely plant-based but with an occasional supplement of meat” |

| UK [75] | Flexitarian | “eating less meat” |

| USA [76] | Semi-vegetarian | “…those who avoid red meat but consume fish and poultry” “A person who eats fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy products, eggs, seafood, and chicken but no red meat.” |

| USA [77] | Semi-vegetarian | “A diet that allowed moderate intake of meat” |

| USA [78] | Semi-vegetarian | “those who limit meat intake” |

| USA [12] |

| “Cutting back on meat rather than abstaining completely.” |

| USA [79] | Semi-vegetarian | “limits meat” Contains all foods, including meat, poultry, fish and shellfish, eggs, and dairy, in addition to plant-based foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes/beans. However, red meat is limited to 1 time/week; poultry is limited to 5 time/week or less. |

| USA [80] | Flexitarian | “…consisted of high amounts of fruits, whole-grain cereals, and nuts, low but not null amounts of meat and high amounts of dairy products.” |

| USA [81] | Flexitarian | “Eating as a semi-vegetarian style” |

| USA [82] | Flexitarian | “There is a growing need for Americans to shift from a meat-centered diet to a plant-based diet, with meat on the side or in moderation; this is known as a flexitarian diet.” |

| USA [83] | Flexitarian | “Choosing to reduce meat, dairy, and eggs in favor of more plant-based foods to benefit the environment, improve health, or both.” |

| USA [84] | Flexitarian | This journal/authors considered flexitarians as those households that “frequently consumed both dairy milk and plant-based beverages.” |

| USA [85] |

| Flexitarian Flip: “dietary shift from the traditional meat-centric diet of Western society to a semi-vegetarian diet” |

| USA [86] | Semi vegetarian | “Semi vegetarians may consume dairy products and/or eggs, eat some meat (red meat and poultry) ≥1 time/month, and the total of fish and meat ≥1 time/month, but <1 time/week.” |

| USA [87] | Semi-vegetarian | “Those who ate fish and poultry, but < 1 time/week” Authors defined semi-vegetarians as those “who reported consuming fruits, vegetables, pulses or beans, animal products (chicken or meat, eggs, milk or curd) either daily, weekly, or occasionally, but no fish” |

| USA/Canada [88] | Semi-vegetarian | “Partially vegetarian diet; consuming meat more often than once a month but less than once per week.” |

| USA/Canada [89] | Semi-vegetarian | “Semi-vegetarians if intake of red meds, poultry or fish, but not only first was more than or equal to once per month but less than once per week” |

| USA/Canada [90] | Semi-vegetarian | “Semi-vegetarians were defined as consuming fish at any frequency both consuming other meats <1 time/month or total meat (with red meat and poultry ≥1 time/month and the total of all meats <1 time/week.” |

| USA/Canada [91] | Semi-vegetarian | “Semi-vegetarians ate red meat, poultry, fish 1 time/month to 1 time/week and eggs or dairy at any level |

| USA/Canada [92] | Semi-vegetarian | “…ate a total of red meat or poultry ≥1 time/month but all meats combined (including fish) <1 time/week and eggs/dairy in any amount |

| USA/Canada [93] | Semi-vegetarian | “Consuming dairy products and/or eggs and meat (red meat and poultry ≥ 1 time/month and <1 time/week)” |

| USA/Canada [94] | Semi-vegetarian | “semi-vegetarians consumed dairy products and/or eggs and (red meat and poultry ≥1 time/month and <1 time/week)” |

| USA/Canada [95] | Semi-vegetarian | “Semi-vegetarians consumed red meat, poultry and fish less than once per week but more than once per month.” |

| USA [96] |

| “flexible in the degree to which one consumes meat…there are levels to meat consumption within flexitarianism” |

| USA [97] |

| “consumers who limit their consumption of certain types of meat, such as red meat, poultry, or fish, either in terms of frequency or portion size” |

| West Africa [98] | Flexitarian | “limitation in consuming meat without being exclusively vegetarian and regardless of financial situation” |

| Name of Country/Region [Citation] | Year(s) | Dairy Recommendations for ~2000 kcal Diet | Meat/Poultry/Egg Recommendations for ~2000 kcal Diet | Fish/Seafood Recommendations for ~2000 kcal Diet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan [14] | 2016 | 3.5 servings (each serving is ~70 kcal) | 2 servings (meat, fish and eggs combined into one group; each serving is ~70 kcal) | |

| Albania [127] | 2008 | 3 portions (1 portion is 200 mL milk, 150–180 g yogurt, 60–90 g curdle cheese) | 1 portion (meat, fish, eggs, and cheese combined into one group; 100–120 g meat or fish, 2–3 eggs, 200 g fresh cheese, 50–60 g ripened cheese) | |

| Australia [105] | 2013 | 2.5 to 4 serves (1 serve is 1 cup milk, cup evaporated milk, cup yogurt | 2 to 2.5 serves (meat, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds, and legumes/beans in one group; 65 g meat, 80 g poultry, 100 g cooked fish, 2 eggs, 150 g cooked beans/legumes, 170 g tofu, 30 g nuts/seeds) | |

| Bangladesh [128] | 2013 | 130 g milk or milk product (plain curd) or soya milk | 40 g poultry and meat; 30 g eggs | |

| Barbados [51] | 2017 | 3 mealtime portions per day of “foods from animals” (mealtime portions are equal to an “amount up to the size of the palm or your hand and the thickness of your little finger”) | ||

| Belgium [49] | 2019 | 250 to 500 mL | Maximum 300 g red meat per week; Poultry, eggs, or other meat substitutes 1 to 3 times per week | 1–2 times per week (1 time should be oily fish) |

| Belize [78] | 2012 | 7 portions (defined as portions that give 73–75 kcal) of “foods from animals” daily (meat, fish, milk, eggs, cheese) | ||

| Bulgaria [50] | 2006 | 1 glass milk or yogurt (200 mL) and 50 g cheese | Poultry or lean red meat up to 3 times per week (100 g/serving) | 1–2 times per week (150–200 g per serving) |

| England [52] | 2016 | No quantitative recommendations provided for adults | No more than 70 g red meat per day | 2 times per week (140 g each; 1 time should be oily fish) |

| Ethiopia [72] | 2022 | 300–400 g | 60 g “animal-source foods such as eggs and meat” (fish is depicted as belonging to this food group) | |

| Fiji [43] | 2013 | 2 meals per day should include “bodybuilding foods” (meat, fish/seafood, poultry, eggs, dairy) | ||

| Geogia [53] | 2005 | 2–3 portions milk, yogurt, sour milk, cheese (250 mL milk; 125 mL yogurt/sour milk; 30 g cheese) | 1–3 portions meat, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes (80 g meat, poultry, or fish; 1 egg; cup beans) | |

| Germany [46] | 2024 | Daily | No more often than weekly (up to 300 g meat and sausage) | 1–2 portions weekly |

| Ghana [54] | 2023 | 1.5 servings animal source foods (144 g/day; 1 serving = 45–135 g boiled beef or goat, 57–75 g poultry, milk, 67.5–152 g fish, 2 eggs) The variation in serving size reflects different serving size for different types of red meat, poultry, and fish) | ||

| India [136] | 2024 | 300 mL milk or curd | 85 g pulses and legumes (30 g can be substituted with fish or meat) | |

| Ireland [55] | 2016 | 3 servings (200 mL milk or yogurt drink, 124 g yogurt, 25 g cheese) | 2 servings of protein foods (50–75 g meat/poultry, 100 g fish, 2 eggs, cup beans, 40 g nuts or seeds) | Up to twice weekly as part of protein foods servings |

| Israel [56] | 2019 | Daily | About 2–3 portions chicken/turkey per week; no more than 300 g per week meat | At least 1 portion weekly |

| Jamaica [73] | 2015 | 5 servings food from animals (75 kcal meat or whole milk or 40 kcal skim milk) | ||

| Japan [58] | 2010 | 2 servings | 3–5 servings meat, fish, egg, and soybean dishes | |

| Kenya [59] | 2017 | Daily (250 mL milk or yoghurt) | 2 times per week (eat 30 g lean meat, fish/seafood, poultry, insects, eggs) | |

| Lebanon [60] | 2013 | 3 servings (1 cup milk or yogurt, 3 tablespoons powdered milk, 45 g cheese, 8 tablespoons labneh) | 5–6.5 servings (1 serving = 30 g meats, 1 egg, cup legumes, 15 g nuts and seeds) | 2 servings weekly, at least one from a fatty fish (90 g) |

| Netherlands [61] | 2015 | A few portions | Limit red meat consumption | Weekly (preferably fatty fish) |

| New Zealand [62] | 2020 | 2.5–4 servings (1 cup milk or fortified alternative, 40 g cheese, 200 g yogurt) | 2–3 servings legumes, nuts, seeds, fish/seafood, eggs, poultry, red meat (150 g beans/legumes, 170 g tofu, 30 g nuts/seeds, 100 g fish, 2 eggs, 100 g chicken, 65 g meat; less than 500 g cooked meat weekly) | |

| Nordic [16] | 2023 | 350 mL to 500 mL milk and dairy foods or fortified plant-based alternatives | Less than 350 g red meat per week and minimal intake of poultry | 300–450 g weekly (at least 200 g from fatty fish) |

| Norway [63] | 2014 | Daily | Less than 500 g meat per week | 300–450 g weekly (at least 200 g from fatty fish) |

| Oman [57] | 2024 | 3 servings (1 cup milk or yogurt, 3 tablespoons powdered milk, 45 g cheese) | 5.5 servings fish, poultry, meats, eggs, legumes, nuts and seeds (1 serving = 30 g fish, poultry, or meat, 1 egg, cup legumes, 1 tablespoon peanut butter, 15 g nuts or seeds); no more than 300 g red meat per week | 2–3 servings per week as part of protein food intake |

| Pacific Community [17] | 2018 | 1/6 of the food eaten each day should be “bodybuilding foods” such as fish, lean meat, eggs, beans, and milk (one portion of meat is the palm of your hand) | ||

| Philippines [64] | 2012 | 1 serving (1 glass milk, evaporated milk, 4 tablespoons milk powder) | 3–4 servings fish, lean meat, poultry, egg, cheese, dried beans or nuts (1 medium piece fish, 1/3 cup shelled shellfish, 1 egg, 1 slice cheese, 3 cubic centimeters meat/poultry) | |

| Qatar [65] | 2015 | Daily (1 cup yogurt or milk, 14 tablespoons labneh, 50 g cheese) | No quantitative guidance listed | Twice weekly |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis [74] | 2010 | 7 portions (defined as amounts providing 40 to 75 kcal) of “foods from animals” to be eaten daily | ||

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines [75] | 2021 | 4–8 servings “food from animals” (1 serving = amount equal to 73 kcal; 1 cup milk, 1 oz cheese, 4 oz yogurt, 1 small drumstick, 1 egg, 2 small fish) | ||

| Saudi Arabia [47] | 2012 | 2–3 servings (240 mL milk or laban, 30 g cheese) | 2–3 servings meat and legumes (60–90 g meat/poultry/fish/seafood, cup cooked legumes, 1 egg, 4 to 6 tablespoons peanut butter) | |

| Seychelles [77] | 2006 | 3 portions | Meat/poultry/eggs not mentioned | 5 times weekly |

| Sierra Leone [66] | 2016 | Daily serving of fish, poultry, meat, milk or eggs | ||

| South Africa [76] | 2013 | 400–500 mL milk, maas, yogurt, cottage cheese, cheese | No more than 560 g red meat weekly; 3–4 eggs weekly | 2–3 per week (80–90 g per portion) |

| Spain [45] | 2022 | Maximum 3 servings daily (1 serving = 200–250 mL milk, 40–60 g hard cheese, 85–125 g soft cheese, 125 g yogurt) | Maximum 3 servings per week of meat (1 serving = 100–125 g) or up to 4 eggs | 3 or more servings per week (1 serving = 125–150 g) |

| Sri Lanka [44] | 2021 | –1 servings (100–200 mL) of milk or fermented milk can be included but not needed daily | 1 egg can be eaten daily; Fish recommended daily; 2–4 servings of lean meat or fish can be eaten daily | |

| Sweden [67] | 2015 | 2–5 dL milk, curdled milk, yogurt | No more than 500 g meat | 2–3 times weekly (at least 1 serving fatty fish) |

| Turkey [137] | 2006 | 2 servings (1 serving = 200 cc milk or yogurt or matchstick size cheese) | Limited amounts of meat; eggs can be a substitute | 2 times per week |

| U.S. [15] | 2020–2025 | 3 cup-equivalents | 26 ounce-equivalents (per week) | 8 ounce-equivalents (per week) |

| Zambia [68] | 2021 | 1 serving (245 g milk or yogurt or 1/3 cup cheese) | 1 serving poultry, fish, eggs, insects, caterpillars (50–115 g), choosing fish as often as possible | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hess, J.M.; Robinson, K.; Scheett, A.J. Vegetarianísh—How “Flexitarian” Eating Patterns Are Defined and Their Role in Global Food-Based Dietary Guidance. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142369

Hess JM, Robinson K, Scheett AJ. Vegetarianísh—How “Flexitarian” Eating Patterns Are Defined and Their Role in Global Food-Based Dietary Guidance. Nutrients. 2025; 17(14):2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142369

Chicago/Turabian StyleHess, Julie M., Kaden Robinson, and Angela J. Scheett. 2025. "Vegetarianísh—How “Flexitarian” Eating Patterns Are Defined and Their Role in Global Food-Based Dietary Guidance" Nutrients 17, no. 14: 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142369

APA StyleHess, J. M., Robinson, K., & Scheett, A. J. (2025). Vegetarianísh—How “Flexitarian” Eating Patterns Are Defined and Their Role in Global Food-Based Dietary Guidance. Nutrients, 17(14), 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142369