Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review

Abstract

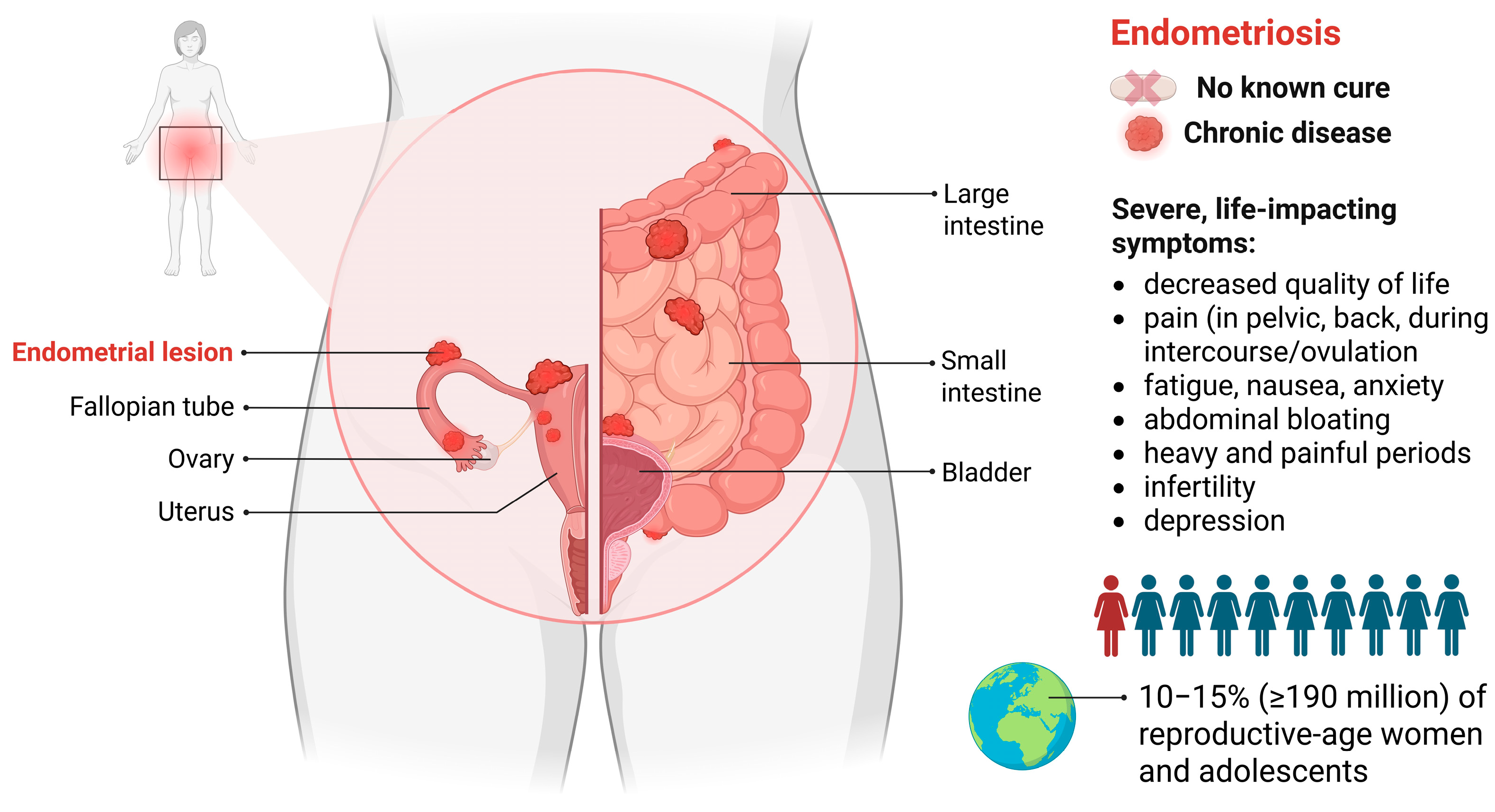

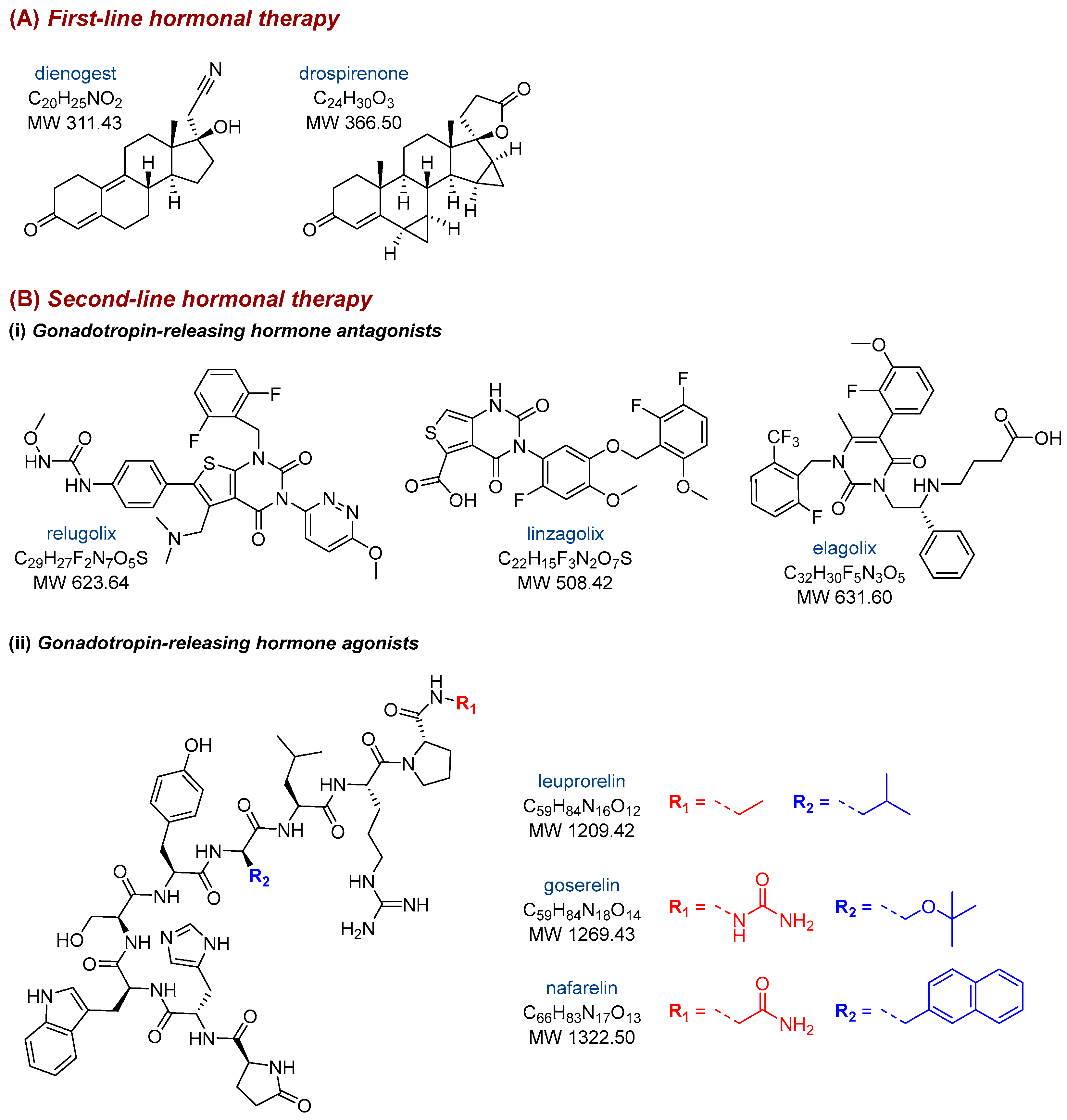

1. Introduction

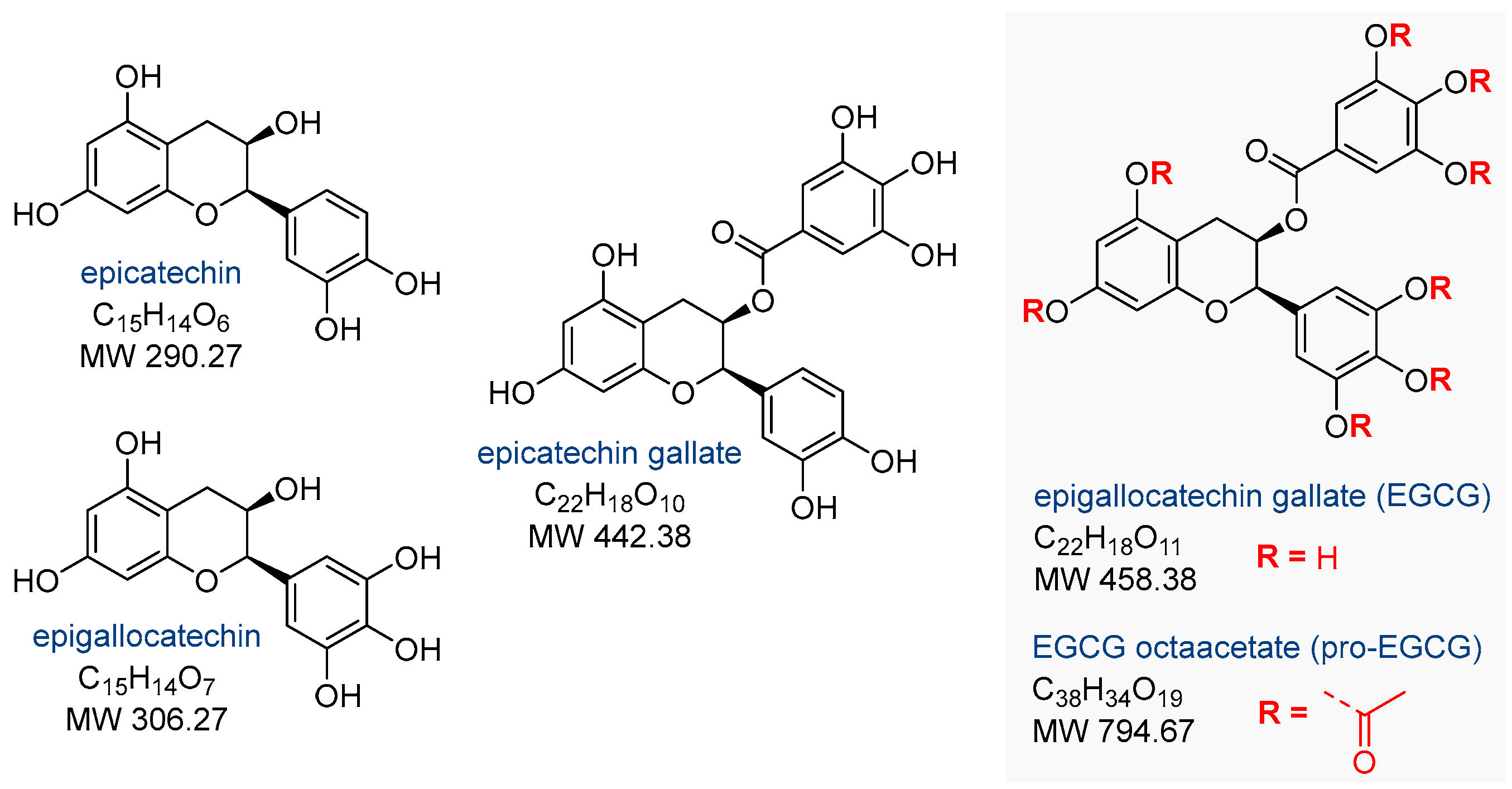

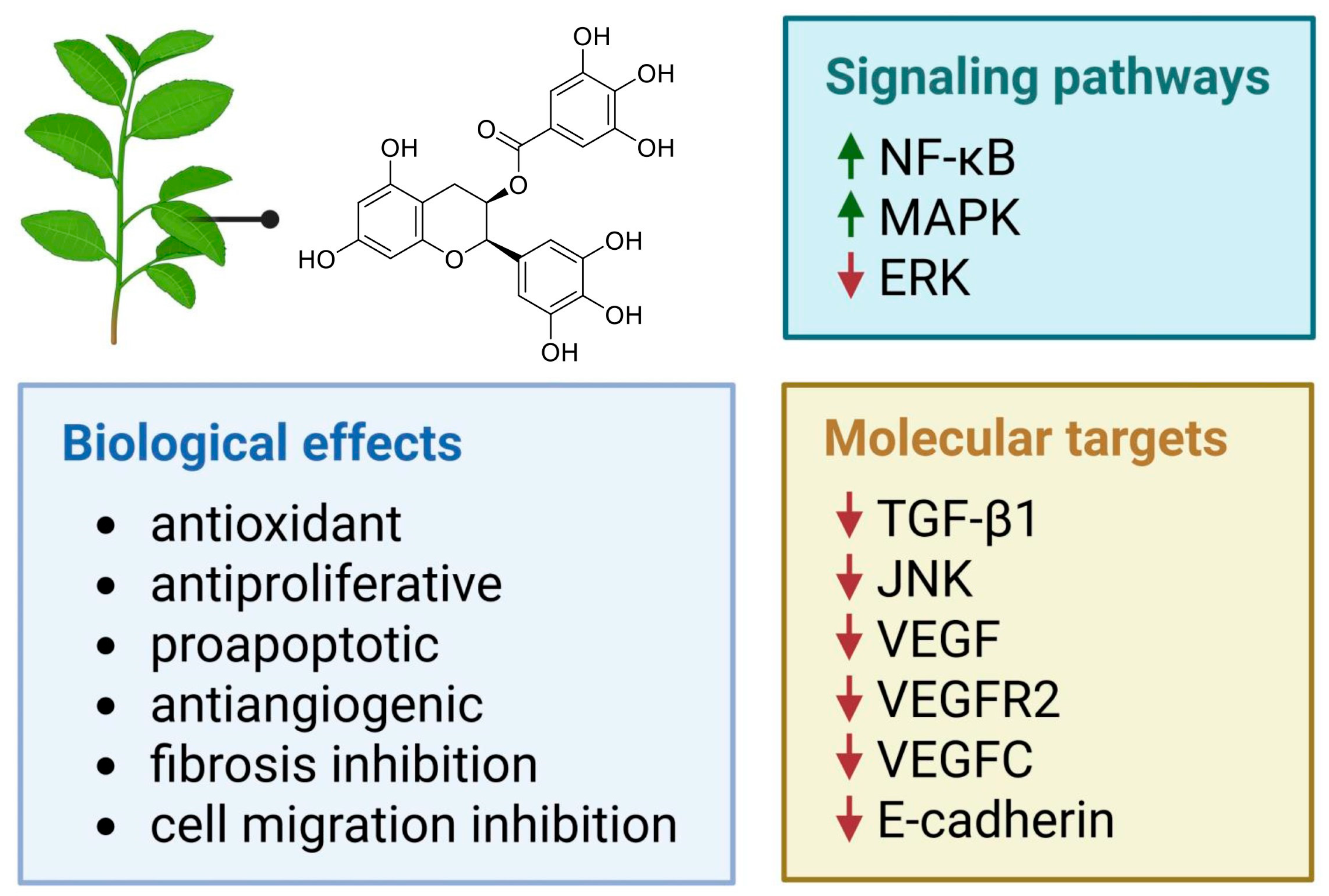

2. Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate on Endometriosis

2.1. In Vitro and In Vivo Activity of Epigallocatechin Gallate

2.2. Activity of the Peracetylated Prodrug of Epigallocatechin Gallate

2.3. Activity of Epigallocatechin-Gallate-Based Nanoparticles

2.4. Potential Limitations of the Studies

3. Literature Search Strategy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alonso, A.; Gunther, K.; Maheux-Lacroix, S.; Abbott, J. Medical management of endometriosis. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 36, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasar, P.; Ozcan, P.; Terry, K.L. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Curr. Obstet. Gynecol. Rep. 2017, 6, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, F.L.; McKinnon, B.D.; Mortlock, S.; Fitzgerald, H.C.; Zhang, C.; Montgomery, G.W.; Gargett, C.E. New concepts on the etiology of endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 1090–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, M.; Matsuzaki, K.; Harada, M. Endometriosis, a common but enigmatic disease with many faces: Current concept of pathophysiology, and diagnostic strategy. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.H.; Lazim, N.; Sutaji, Z.; Abu, M.A.; Abdul Karim, A.K.; Ugusman, A.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mokhtar, M.H.; Ahmad, M.F. HOXA10 DNA methylation level in the endometrium women with endometriosis: A systematic review. Biology 2023, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, K.; Nakayama, K.; Razia, S.; Islam, S.H.; Farzana, Z.U.; Sonia, S.B.; Yamashita, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Ishibashi, T.; Imamura, K.; et al. Association between KRAS and PIK3CA mutations and progesterone resistance in endometriotic epithelial cell line. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 3579–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, K.; Sivasankar, V. MicroRNAs—Biology and clinical applications. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2014, 18, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zhu, M.; Li, W. Advances in research on malignant transformation of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1475231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corte, P.; Klinghardt, M.; von Stockum, S.; Heinemann, K. Time to diagnose endometriosis: Current status, challenges and regional characteristics—A systematic literature review. BJOG 2025, 132, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nati, I.D.; Malutan, A.M.; Ciortea, R.; Bucuri, C.; Rada, M.P.; Ormindean, C.M.; Mihu, D. Endometriosis reccurence—Is ultrasound the solution? Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 2024, 20, e050423215451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M.C.M.; Ferreira, L.P.S.; Della Giustina, A. It is time to change the definition: Endometriosis is no longer a pelvic disease. Clinics 2024, 79, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.; Shebl, O.; Shamiyeh, A.; Oppelt, P. The rASRM score and the Enzian classification for endometriosis: Their strengths and weaknesses. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2013, 92, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, S.; Kaya, H.E.; Zeppernick, F.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Keckstein, J.; Yildiz, S.M.; Nurkan, E.; Krombach, G.A.; Roller, F.C. Application of the #Enzian classification for endometriosis on MRI: Prospective evaluation of inter- and intraobserver agreement. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1303593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaffarino, F.; Cipriani, S.; Ricci, E.; Esposito, G.; Parazzini, F.; Vercellini, P. Histologic subtypes in endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer and ovarian cancer arising in endometriosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 31, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adilbayeva, A.; Kunz, J. Pathogenesis of endometriosis and endometriosis-associated cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driva, T.S.; Schatz, C.; Haybaeck, J. Endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas: How PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway affects their pathogenesis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, J.; Suker, A.; White, L. Endometriosis: A review of recent evidence and guidelines. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 53, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.G.; Olivares, C.N.; Bilotas, M.A.; Bastón, J.I.; Singla, J.J.; Meresman, G.F.; Barañao, R.I. Natural therapies assessment for the treatment of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lin, A.; Qi, L.; Lv, X.; Yan, S.; Xue, J.; Mu, N. Immunotherapy: A promising novel endometriosis therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1128301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meresman, G.F.; Götte, M.; Laschke, M.W. Plants as source of new therapies for endometriosis: A review of preclinical and clinical studies. Hum. Reprod. Update 2021, 27, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anvari Aliabad, R.; Hassanpour, K.; Norooznezhad, A.H. Cannabidiol as a possible treatment for endometriosis through suppression of inflammation and angiogenesis. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2024, 12, e1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, D.A.M.; Salamt, N.; Zaid, S.S.M.; Mokhtar, M.H. Beneficial effects of green tea catechins on female reproductive disorders: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochman, J.; Jakubczyk, K.; Antoniewicz, J.; Mruk, H.; Janda, K. Health benefits and chemical composition of matcha green tea: A review. Molecules 2020, 26, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczyk, M.; Ciebiera, M.; Nowicka, G.; Łoziński, T.; Ali, M.; Al-Hendy, A. Epigallocatechin gallate for the treatment of benign and malignant gynecological diseases—Focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Nutrients 2024, 16, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. EGCG-based nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 2177–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Man, G.C.W.; Hung, S.W.; Zhang, T.; Fung, L.W.Y.; Cheung, C.W.; Chung, J.P.W.; Li, T.C.; Wang, C.C. Therapeutic effects of green tea on endometriosis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3222–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, S.W.; Gaetani, M.; Li, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, R.; Ding, Y.; Man, G.C.W.; Zhang, T.; Song, Y.; et al. Distinct molecular targets of ProEGCG from EGCG and superior inhibition of angiogenesis signaling pathways for treatment of endometriosis. J. Pharm. Anal. 2024, 14, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Darcha, C. Antifibrotic properties of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lui, W.T.; Chu, C.Y.; Ng, P.S.; Wang, C.C.; Rogers, M.S. Anti-angiogenic effects of green tea catechin on an experimental endometriosis mouse model. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschke, M.W.; Schwender, C.; Scheuer, C.; Vollmar, B.; Menger, M.D. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits estrogen-induced activation of endometrial cells in vitro and causes regression of endometriotic lesions in vivo. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 2308–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Becker, C.M.; Lui, W.T.; Chu, C.Y.; Davis, T.N.; Kung, A.L.; Birsner, A.E.; D’Amato, R.J.; Wai Man, G.C.; Wang, C.C. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses vascular endothelial growth factor C/vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 expression and signaling in experimental endometriosis in vivo. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Q.; Shi, W.; Zhou, L.; Tao, A.; Li, L. Effect of epigallocatechin-3-gallate on the status of DNA methylation of E-cadherin promoter region on endometriosis mouse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 2076–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Tang, C.; Rao, J.; Xue, Q.; Wu, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, A.; Chen, L.; Shen, Z.; Lei, L. Systematic identification of the druggable interactions between human protein kinases and naturally occurring compounds in endometriosis. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2017, 71, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.; Lu, X.; Tao, F.; Tukhvatshin, M.; Xiang, F.; Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Lin, J.; Hu, Y. The potential mechanisms of catechins in tea for anti-hypertension: An integration of network pharmacology, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulation. Foods 2024, 13, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, K.A.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Yu, C.W.; Lim, D.S. Anti-platelet effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in addition to the concomitant aspirin, clopidogrel or ticagrelor treatment. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Awajan, D.; Alqudah, A.; Alsawwaf, R.; Althunibat, R.; Abu AlRoos, M.; Al Safadi, A.; Abu Asab, S.; Hadi, R.W.; Al Kury, L.T. Targeting cancer hallmarks with epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): Mechanistic basis and therapeutic targets. Molecules 2024, 29, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Xu, H.; Man, G.C.W.; Zhang, T.; Chu, K.O.; Chu, C.Y.; Cheng, J.T.Y.; Li, G.; He, Y.X.; Qin, L.; et al. Prodrug of green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (Pro-EGCG) as a potent anti-angiogenesis agent for endometriosis in mice. Angiogenesis 2013, 16, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.W.; Liang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chung, P.W.J.; Chan, T.H.; Wang, C.C. An in-silico, in-vitro and in-vivo combined approach to identify NMNATs as potential protein targets of ProEGCG for treatment of endometriosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 714790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Chakravarty, B.; Chaudhury, K. Nanoparticle-assisted combinatorial therapy for effective treatment of endometriosis. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 11, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hooghe, T.M. Clinical relevance of the baboon as a model for the study of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 68, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoga, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeuchi, H.; Yamasaki, S.; Sasahara, N.; Hoshi, T.; Kinoshita, K. Fibrosis and smooth muscle metaplasia in rectovaginal endometriosis. Pathol. Int. 2003, 53, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, S.; Ragni, N.; Remorgida, V. Antiangiogenic therapies in endometriosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 149, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelbrunn, M.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Intercellular communication: Diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brücher, B.L.D.M.; Jamall, I.S. Cell-cell communication in the tumor microenvironment, carcinogenesis, and anticancer treatment. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 34, 213–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| In Vitro Model | Animal Model | EGCG Treatment | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue samples from 31 reproductive-aged patients, including 16 patients with untreated endometriosis (stages I and II, as classified by ASRM) and 15 control patients without endometriosis | 56 adult (2 months old) female BALB/c mice with endometriosis-like lesions induced via autologous transplantation of one uterine horn to the bowel mesentery | In vitro tests: 0, 20, 40, 80, or 100 µM Animal studies: 20 mg/kg/day or 100 mg/kg/day by esophageal gavage for four weeks | EGCG treatment reduced the mean number and volume of established endometriotic lesions, inhibited cellular proliferation, decreased vascular density, and enhanced apoptotic activity within the lesions. EGCG also reduced proliferation and promoted apoptosis in primary cultures of human endometrial epithelial cells | [19] |

| Endometrial and endometriotic tissue samples collected from 45 patients (median age: 31.0 years; range: 22–36) with histologically confirmed deep endometriosis and from 10 control patients without endometriosis, including 6 with uterine myomas (median age: 31.5 years; range: 28–34) and 4 with tubal infertility (median age: 29.0 years; range: 26–32) | 40 adult (7–8 weeks old) female Swiss nude mice, which received a single injection of proliferative endometrial tissue derived from ten distinct donor samples after the acclimation period | In vitro tests: 50 or 100 µM Animal studies: 50 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections on day 7 or 14 after endometrial tissue implantation and continued for two weeks | EGCG treatment suppressed the proliferation, migration, and invasion of endometrial and endometriotic stromal cells derived from patients with endometriosis. In vivo studies further demonstrated that EGCG attenuated the progression of fibrosis associated with endometriosis | [29] |

| Adult (6 weeks old) female SCID mice with eutopic endometrium transplanted from endometriosis patients (stage III, as classified by ASRM) | 5 mg/kg/day or 50 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections for two weeks | Endometriotic lesions were smaller after EGCG treatment. Angiogenesis within the lesions and surrounding tissues was underdeveloped, and apoptotic activity within the lesions was increased | [30] | |

| Isolated hamster endometrial stromal and glandular cells | Female Syrian golden hamsters (8–10 weeks old) with endometrial fragments and ovarian follicles transplanted into the dorsal skinfold chambers | In vitro tests: 40 µM Animal studies: 65 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections for three days or two weeks | EGCG suppressed E2-induced activation, proliferation, and VEGF expression in endometrial cells, inhibited angiogenesis and reduced blood perfusion in endometriotic lesions, promoted regression of endometriotic lesions, and downregulated VEGF expression in the eutopic endometrium | [31] |

| Human microvascular endothelial cells | 30 adult (6 weeks old) female mice with endometrium transplanted from endometriosis patients (stage III, as classified by ASRM) | In vitro tests: 10–50 μM Animal studies: 50 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections for three weeks | EGCG exhibited antiangiogenic activity in endometriosis by inhibition of this process and selective suppression of the expression and signaling of VEGFC and its receptor VEGFR2 | [32] |

| 36 adult (6–8 weeks old) female BALB/c mice with transfected endometrial fragments obtained from patients aged 44–52 who had undergone hysterectomy due to ovarian endometriotic cysts and uterine myomas | 8.333 mg/mL by i.p. injections every other day over 16 days | EGCG suppressed the growth of endometrial lesions and reduced the expression of E-cadherin | [33] |

| In Vitro Model | Animal Model | Pro-EGCG Treatment | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human endometrial stromal SHT290 cell line, human endometriotic HS293 (C). T cell line | Adult (8 weeks old) female C57BL/6 mice bearing subcutaneously transplanted endometrial tissue, implanted into subcutaneous pockets located on the abdominal wall of each recipient | In vitro tests: 0–300 μM Animal studies: 25 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg taken orally for four weeks | Pro-EGCG exhibited a more potent inhibitory effect on lesion growth compared to EGCG. The prodrug showed efficacy in suppressing lesion development, enhancing apoptosis within lesions, downregulating the angiogenic marker CD31, and preventing lesion recurrence. Pro-EGCG did not impact body weight or alter endogenous levels of female hormones | [28] |

| 32 NOD-SCID mice with homologous endometrium subcutaneously transplanted from 8-week-old female CMV-Luc mice | 50 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections for four weeks | Pro-EGCG suppressed the development, growth, and angiogenesis of experimental endometriosis in mice, demonstrating superior efficacy, enhanced bioavailability, and stronger antioxidant and antiangiogenic properties compared to native catechin | [38] | |

| Primary human endometrial stromal cells isolated from a single healthy female donor without a diagnosis of endometriosis | Adult (8 weeks old) female C57BL/6 mice with subcutaneously transplanted endometriotic tissues of the uterine fragments from the mouse donor group | In vitro tests: 0–300 μM Animal studies: 50 mg/kg/day by i.p. injections for three weeks | Pro-EGCG upregulated the expression of the NMNAT enzymes | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markowska, A.; Kojs, Z.; Antoszczak, M.; Markowska, J.; Huczyński, A. Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132068

Markowska A, Kojs Z, Antoszczak M, Markowska J, Huczyński A. Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(13):2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkowska, Anna, Zbigniew Kojs, Michał Antoszczak, Janina Markowska, and Adam Huczyński. 2025. "Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review" Nutrients 17, no. 13: 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132068

APA StyleMarkowska, A., Kojs, Z., Antoszczak, M., Markowska, J., & Huczyński, A. (2025). Epigallocatechin Gallate as a Potential Therapeutic Agent in Endometriosis: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 17(13), 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132068