1. Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic food antigen-mediated disease characterized by a local eosinophilic inflammation of the esophagus. It is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 2000 individuals, but its incidence has been increasing. In pediatric EoE (PedEoE), symptoms vary depending on the age of the child, with vomiting, nausea, and feeding difficulties resulting in failure to thrive being prominent in young children and night-time cough, epigastric pain, dysphagia, and even food impaction in older children and adolescents [

1,

2,

3]. The diagnosis of EoE requires a combination of symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, macroscopic evidence of esophageal inflammation observed during endoscopy, and histological confirmation of eosinophilic infiltration—defined as at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field—in esophageal biopsy specimens obtained from multiple levels of the esophagus [

1,

4]. The management of PedEoE necessitates a multidisciplinary approach. According to the PedEoE guidelines published in 2014, high-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were recommended as the first-line treatment. For patients who did not achieve remission with PPI therapy, the guidelines recommended either topical corticosteroid (tCS) therapy or dietary elimination strategies [

5]. The updated PedEoE guidelines now recommend PPIs, tCS, and dietary therapy as equally valuable first-line treatments for PedEoE [

4]. The choice among these options should be tailored to the individual patient’s clinical situation and preferences. In Europe, the six most common dietary triggers for EoE are cow’s milk (CM), hen’s egg (HE), wheat, soy, (pea)nuts, and (shell)fish. When dietary elimination is selected, it involves the complete avoidance of one or more of these triggers, implemented either through a step-down or step-up approach [

6]. Therapeutic efficacy is evaluated using a combination of symptom scoring and follow-up endoscopies. The primary objectives of treatment include achieving symptom relief, improving quality of life (QoL), and preventing long-term complications such as esophageal strictures and fibrosis, which are associated with persistent eosinophilic infiltration [

7].

Although EoE is generally considered a non-IgE-mediated disorder in adults, more recent literature indicates that 40–74% of children diagnosed with EoE exhibit concomitant IgE-mediated food sensitization or allergy [

1,

8]. Additionally, the occurrence of EoE following tolerance induction protocols or during oral immunotherapy for a specific food further suggests a link between EoE and IgE-mediated food allergy [

8]. This highlights the necessity of tailoring therapeutic approaches to each individual patient. A standardized dietary strategy may not be universally applicable in patients with EoE, particularly in the context of concomitant IgE-mediated food allergies. For instance, the reintroduction of a specific food in a patient with an IgE-mediated allergy after tolerance acquisition over time may—even if perfectly tolerated—still lead to EoE symptoms if that food is also a trigger of their EoE. This underscores the importance of a personalized approach that considers both the immunological complexity and the potential interplay between EoE and IgE-mediated food allergy.

The primary aim of this study is to prospectively document dietary habits and restrictions over a period of at least 12 months in children diagnosed with EoE, with or without concomitant IgE-mediated food allergy, at a single center. A secondary aim is to evaluate the impact of dietary management—compared to pharmacological treatments (PPI or tCS)—on the QoL of both patients and their families. The study also explores whether adjustments in dietary guidance affect QoL outcomes in this population.

4. Discussion

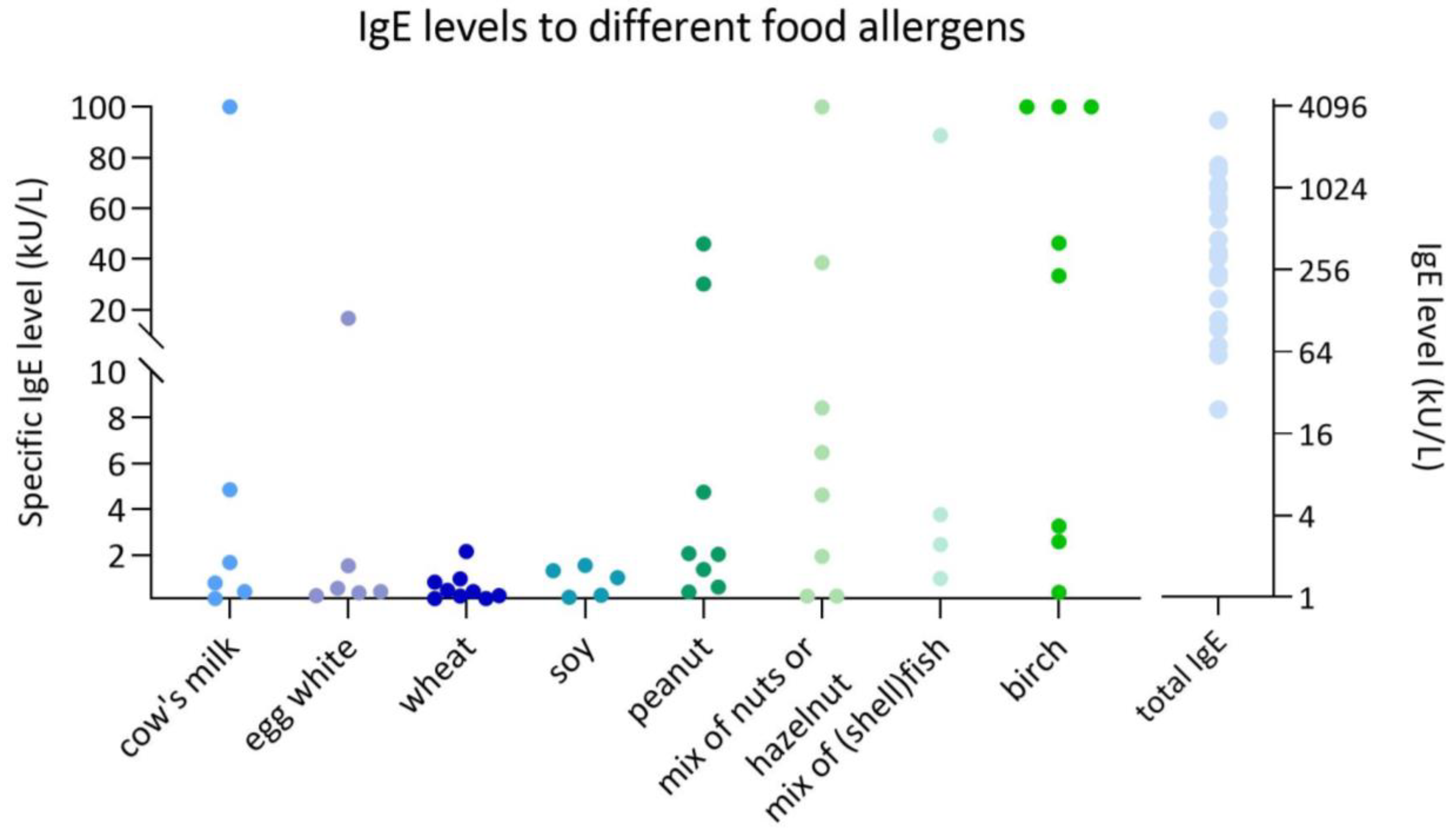

This study provides novel insights into the difficult overlap between food-specific IgE sensitization/allergy and eosinophilic inflammation in children with EoE. Our findings suggest that IgE sensitization is prevalent among pediatric EoE patients and may have clinical implications for EoE disease management and patient well-being.

A key observation in our study was the high prevalence of IgE sensitization to food allergens in children with EoE. This finding aligns with prior research indicating that EoE is frequently associated with allergic comorbidities in children with EoE, including IgE-mediated food allergies and environmental allergies [

1]. While the high prevalence of IgE sensitization is not a novel finding in itself, documenting these data within a real-world, single-center pediatric cohort in Belgium adds value by contributing geographic and clinical context. Regional variations in dietary habits, allergen exposure, and clinical management practices can influence sensitization patterns. Therefore, the documentation of these local data may contribute to a more nuanced understanding across populations. The mechanisms underlying this relationship remain incompletely understood, yet it is hypothesized that epithelial barrier dysfunction and immune dysregulation contribute to both EoE and IgE sensitization [

15,

16]. In contrast, IgE-mediated food allergy appears to be less commonly described in adult patients with EoE [

17]. Despite the high prevalence of IgE sensitization to food allergens reported in children with EoE in the literature, clinically manifest allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis are rare [

18]. In our cohort, most reactions were limited to mild cutaneous or gastrointestinal symptoms, and no cases of severe reactions or anaphylaxis were observed. As a result, the presence of sensitization has to be considered in clinical decision-making to guide dietary management, particularly when supported by a suggestive clinical history or diagnostic work-up.

Given this overlap between EoE and IgE-mediated allergies, distinguishing between IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated symptoms poses a clinical challenge, as overlapping manifestations—such as vomiting and abdominal pain—can mimic one another. This differentiation becomes even more difficult in cases of mild IgE sensitization with subtle symptoms. Nevertheless, IgE-mediated food allergy symptoms typically occur rapidly—within two hours after ingestion of the culprit food—whereas EoE is characterized by a delayed onset of symptoms [

19]. The diagnostic complexity highlights the need for a comprehensive evaluation of both IgE-mediated allergic mechanisms and EoE-specific pathophysiology in pediatric patients.

This difficult overlap between food-specific IgE sensitization/allergy and EoE extends to dietary management, which is particularly complex in patients with EoE who also present with IgE-mediated food allergies. Moreover, whereas dietary management for EoE is typically maintained on a continuous basis, dietary avoidance in IgE-mediated food allergy may be temporary and subject to re-evaluation over time [

20,

21]. Indeed, some children eventually outgrow their IgE-mediated food allergy. The development of tolerance, however, follows a variable natural course that depends on the specific food allergen involved. In IgE-mediated CM allergy, the resolution rates have been reported as 19% by four years of age in the United States and 42% by eight years, 64% by the age of twelve years, and 79% by sixteen years of age. In a Korean cohort, 50% of children outgrew their CM allergy at a median age of 8.7 years [

21]. Similarly, for HE allergy, the literature demonstrates that 73–89% of children with an IgE-mediated HE allergy outgrow their allergy by six years of age [

21]. In IgE-mediated wheat allergy, 27% of children in a Thai cohort achieved tolerance by four years of age and 69% by nine years. In a Polish cohort, wheat allergy resolution was observed in 20% of children by four years of age, 52% by eight years, 66% by twelve years, and 76% by eighteen years [

21]. Resolution rates for IgE-mediated soy allergy have not been extensively studied. In a U.S. cohort, tolerance development was observed in 25% of children by four years of age, 45% by six years, and 69% by ten years [

21]. The natural course of tree nut allergy in children remains poorly studied. A 2005 publication reported that 8.9% of children with prior clinical reactivity and sensitization to tree nuts outgrew their allergy. In contrast, resolution rates for IgE-mediated peanut allergy are well documented, with studies indicating that 22% of children and adolescents outgrow peanut allergy by four years of age and 29% by six years [

21]. Natural tolerance development for fish and shellfish is less common compared to other food allergens. A Greek study reported that complete tolerance to fish increased with age, from 3.4% in preschool-aged children to 45% in adolescents. Similarly, a study in Canada estimated resolution rates of 0.6% per person-year for fish and 0.8% per person-year for shellfish [

21]. Mostly, the reintroduction of a specific allergen in IgE-mediated food allergy can be guided by food-specific IgE decline [

22]. However, a decline in IgE levels to a specific food over time does not necessarily indicate that the food can be safely reintroduced, and the presence of specific IgE levels does not necessarily rule out tolerance [

23]. While the absence of immediate IgE-mediated symptoms after ingestion may suggest clinical tolerance, the potential for EoE reactivation remains, necessitating renewed and, later on, continued dietary restriction. These considerations underscore the importance of individualized dietary strategies that address both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated mechanisms of disease.

Besides the decline in specific IgE, a decline in food-specific IgE components might point to partial tolerance induction. Indeed, as observed in IgE-mediated CM or HE allergy, tolerance can develop gradually over time through exposure to progressively less heated forms of the allergen [

24]. The introduction of highly heated proteins can even accelerate the process of tolerance induction [

25]. Potentially, heated allergens could also play a role in food tolerance induction in EoE. In a recent case report, we described two children with EoE (also included in this cohort, P11 and P20) in whom the introduction of extensively heated HE was well tolerated, whereas subsequent exposure to less heated forms of HE (hard-boiled egg and pancake, respectively) resulted in disease reactivation [

26]. These findings suggest that certain heated proteins may be tolerated in some children with EoE. To further investigate whether this approach could safely broaden dietary options, we are currently conducting the PedEoE IgE study (NCT06381219), which explores the feasibility of introducing extensively heated CM or HE in a cohort of children with CM- or HE-induced EoE, while remaining in remission. This might have a positive impact on the children’s QoL.

Indeed, beyond dietary considerations, the impact of multiple food restrictions on QoL in pediatric EoE patients is another critical aspect of EoE management. In our study, we observed that dietary restrictions negatively affected children’s reported QoL and that there is a significant difference in QoL between groups with varying degrees of dietary restriction. Children avoiding one or two food products seem to have better QoL scores (child PedsQL as well as parent PedsQL scores) than those who have to avoid more than two food products and/or those who are on pharmacological treatment only. While our findings suggest better QoL in children following a 1–2 food elimination diet, it is also possible that this observation partially reflects a less severe or less complex disease phenotype in this subgroup. As our study was not powered to adjust for all potential confounding variables, such as disease severity or allergic sensitization complexity, this association should be interpreted in light of the study’s exploratory nature and limited sample size. Despite the limitations imposed by a relatively small sample size, our cohort represents one of the largest single-center pediatric EoE datasets in the Flanders region. Given that eosinophilic esophagitis is considered a rare disease, particularly in children [

3], collecting data from 30 pediatric patients in a single tertiary referral center would still offer valuable insights. Adult patients were deliberately excluded from this study to preserve the homogeneity of the cohort. Pediatric and adult EoE populations differ in disease phenotype, symptomatology, and treatment response, and combining these groups could have introduced additional variability, particularly in the assessment of quality of life, which was conducted using tools specifically validated for pediatric populations. Furthermore, a multicenter design across different regions or countries was not pursued in order to avoid heterogeneity in dietary patterns and feeding practices, which are known to vary significantly by geography and culture. Since dietary management is a central focus of this study, maintaining a consistent regional context was essential to ensure internal validity and interpretability of the findings.

Also, given the observational and non-randomized nature of this study, we cannot exclude the possibility that confounding factors such as disease severity, allergic profile complexity, and parental preferences influenced both treatment choice and QoL outcomes. While this may limit causal interpretation, the real-life setting of the study allows for the inclusion of a diverse patient population that more closely resembles everyday clinical practice. When interpreting the QoL and symptom data, it should be noted that analyses were performed using both all available completed questionnaires per child and only the first completed questionnaire per patient, in order to reduce potential bias introduced by repeated measurements. Although the inclusion of multiple questionnaires from the same individual across follow-up time points may introduce within-subject dependency, this approach was deemed appropriate to capture temporal patterns within a real-world pediatric EoE population. Given the limited sample size and observational design, non-parametric statistical tests were applied. Nonetheless, the use of more advanced statistical techniques, such as mixed-effects models, may be more suitable in future studies with larger cohorts to formally account for repeated measures and potential confounding variables.

Lastly, the accuracy and reliability of questionnaire-based QoL assessments in pediatric EoE patients must be carefully considered. Parental influence during questionnaire completion may introduce bias, as parents may inadvertently guide their child’s responses when present in the room. Additionally, young children may struggle to recall past events accurately, as their sense of time is still developing. These factors should be considered when interpreting QoL data in a young study population.