Why Do Adolescents Skip Breakfast? A Study on the Mediterranean Diet and Risk Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Instruments

- 1–Questionnaire

- Adherence to the Mediterranean diet: Assessed using the KIDMED questionnaire [23], which comprises 16 dichotomous items (YES/NO). Four items indicate lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet (consumption of fast food, pastries, sweets, and skipping breakfast), and twelve items indicate higher adherence (consumption of olive oil, fish, fruits, vegetables, cereals, nuts, legumes, pasta or rice, dairy products, and yogurt). Scores range from −1 to +1 depending on the negative or positive connotation of each item. The total score was dichotomized to simplify interpretation: good adherence (scores 7–12) and poor adherence (scores 0–6). This categorization allowed for clearer identification of adherence levels.

- Breakfast frequency was evaluated using the following question from the PACO Project [24]: “From Monday to Friday during the school year, how many days do you have breakfast?” Participants could choose “5 days”, “4 days”, “3 days”, “2 days”, “1 day”, or “I never eat breakfast on school days”. Students who selected “5 days” were considered regular breakfast consumers. Although breakfast consumption is part of the overall Mediterranean diet adherence index, in this study, both the total KIDMED score and individual items were analyzed as explanatory variables in relation to the main outcome: skipping breakfast (defined independently based on reported weekday frequency).

- Sleep duration: Questions related to sleep habits were based on the Sleep Habits Survey for Adolescents [25]. Participants indicated the exact time they went to sleep and woke up on both school days and weekends. Sleep duration was calculated based on this information.

- Screen time: Measured using the Screen-Time Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (64), employed in the HELENA study [26] and the PASOS study [27]. Participants reported screen time on weekdays. From these data, two dichotomous variables were derived: total screen time (less than or more than 4 h) and adherence to screen time recommendations (less than or more than 2 h per day).

- Physical activity (PA): Assessed through stages of change based on the Prochaska and DiClemente model [28], which includes five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. The first three were classified as non-compliance with physical activity. Enjoyment of PA was also assessed using a Likert-type scale (none, little, somewhat, quite a bit, very much) [24]. The mode of commuting to school was also assessed as active or motorized.

- Well-being: Quality of life was assessed using the EQ-5D-Y-3L questionnaire from the EuroQol Group in its youth version, which includes five dimensions related to health (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and worry/sadness), with three response levels (“No problems”, “Some problems”, “A lot of problems”) [29]. For the purpose of breakfast analysis, only the “pain/discomfort” and “worry/sadness” dimensions were considered.

- Family and environmental variables: Monthly household income was categorized as less than EUR 1000; EUR 1000–EUR 1999; EUR 2000–EUR 2999; and EUR 3000 or more. Residential environment was classified as urban (living in a municipality with 10,000 or more inhabitants) or non-urban (fewer than 10,000 inhabitants). The usual dinner and bedtime was also noted.

- 2–Anthropometric Measurements: BMI

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics

3.2. Breakfast Habits by Gender

3.3. Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis by Gender

3.3.1. Female Adolescents

| Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do Not Skip Breakfast n (%) | Skip Breakfast n (%) | OR 95% CI | p-Value X2 | OR 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Environment | ||||||

| Urban | 68 (44) | 50 (42) | 1.000 | 0.445 | ||

| Non-urban | 88 (56) | 69 (58) | 1.066 (066–1.73) | |||

| Monthly household income | ||||||

| Less than EUR 1000 | 21 (13) | 12 (10) | 1.000 | 0.484 | ||

| EUR 1000-EUR 1999 | 67 (43) | 59 (50) | 1.541 (0.70–3.40) | |||

| EUR 2000-EUR 2999 | 28 (18) | 20 (17) | 1.250 (0.50–3.11) | |||

| More than EUR 3000 | 23 (15) | 12 (10) | 0.913 (0.34–2.47) | |||

| EQ5D worry/sadness | ||||||

| No problems | 93 (60) | 54 (45) | 1.000 | 0.016 * | 1 | 0.026 * |

| Some problems | 59 (38) | 55 (46) | 1.605 (0.98–2.64) | 1.651 (0.85–3.21) | ||

| A lot of problems | 4 (3) | 10 (8) | 4.306 (1.29–14.40) | 6.438 (1.53–27.04) | ||

| EQ5D pain/discomfort | ||||||

| No problems | 129 (83) | 82 (69) | 1.000 | 0.016 * | ||

| Some problems | 26 (17) | 33 (28) | 1.997 (1.11–3.58) | |||

| A lot of problems | 1 (1) | 4 (3) | 6.293 (0.69–57.29) | |||

| Enjoy physical activity (PA) | ||||||

| None | 2 (1) | 6 (5) | 1.000 | 0.351 | ||

| Little | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.417 (0.05–3.31) | |||

| Somewhat | 47 (30) | 30 (25) | 0.213 (0.04–1.12) | |||

| Quite a bit | 59 (38) | 44 (37) | 0.249 (0.05–1.29) | |||

| Very much | 44 (28) | 34 (29) | 0.258 (0.05–1.36) | |||

| PA recommendations | ||||||

| Does not meet | 52 (33) | 43 (36) | 1.000 | 0.360 | ||

| Meets | 104 (67) | 76 (64) | 0.628 (0.54–1.46) | |||

| Commuting to school | ||||||

| Active | 89 (57) | 75 (63) | 1.000 | 0.168 | ||

| Motorized | 67 (43) | 43 (36) | 0.762 (0.47–1.24) | |||

| Screen time | ||||||

| Less than 4 h | 93 (60) | 59 (50) | 1.000 | 0.062 | ||

| 4 h or more | 63 (40) | 60 (50) | 1.501 (0.93–2.43) | |||

| Screen time recommendations | ||||||

| Less than 2 h/day | 30 (19) | 19 (16) | 1.000 | 0.295 | ||

| 2 h/day or more | 126 (81) | 100 (84) | 0.798 (0.42–1.50) | |||

| Dinner time | ||||||

| Before 21 pm | 54 (35) | 82 (69) | 1.000 | 0.056 | ||

| Between 21:00 and 21:30 | 57 (37) | 33 (28) | 0.474 (0.26–0.88) | |||

| Between 21:30 and 22:00 | 32 (21) | 4 (3) | 1.055 (0.56–1.98) | |||

| After 22:00 pm | 13 (8) | 0 (0) | 1.038 (0.43–2.49) | |||

| Bedtime | ||||||

| Before 22:00 pm | 20 (13) | 48 (40) | 1.000 | 0.033 * | ||

| Between 22:00 and 23:00 | 72 (46) | 24 (20) | 0.526 (0.25–1.11) | |||

| Between 23:00–24:00 | 34 (22) | 30 (25) | 0.774 (0.34–1.75) | |||

| After 24:00 pm | 30 (19) | 12 (10) | 1.298 (0.58–2.86) | |||

| Sleeping hours | ||||||

| Less than 8 h | 49 (31) | 49 (41) | 1.000 | 0.049 * | ||

| 8 h or more | 107 (69) | 68 (57) | 0.636 (0.39–1.05) | |||

| BMI (Cole) | ||||||

| Normal weight | 117 (75) | 82 (69) | 1.000 | 0.122 | ||

| Overweight/Obesity | 37 (24) | 37 (31) | 1.427 (0.84–2.44) | |||

| KidMed | ||||||

| High adherence | 65 (42) | 74 (62) | 1.000 | <0.001 * | 1 | <0.001 * |

| Low adherence | 91 (58) | 45 (38) | 0.434 (0.27–0.71) | 0.140 (0.06–0.34) | ||

| Kidmed (1.000 = yes) | ||||||

| I have a dairy product for breakfast | 136 (87) | 59 (50) | 0.145 (0.08–0.26) | 0.001 * | 0.238 (0.12–0.48) | <0.001 * |

| I have cereals or grains for breakfast | 88 (56) | 53 (45) | 0.621 (0.38–1.00) | 0.034 * | ||

| I have commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast | 60 (39) | 41 (34) | 0.841 (0.51–1.38) | 0.289 | ||

| I consume a fruit or a fruit juice every day | 93 (60) | 83 (70) | 1.562 (0.94–2.59) | 0.054 | 2.893 (1.34–6.23) | 0.007 * |

| I have a second fruit everyday | 64 (41) | 55 (46) | 1.235 (0.76–2.0) | 0.230 | ||

| I have fresh or cooked vegetables regularly once a day | 102 (65) | 81 (68) | 1.128 (0.68–1.87) | 0.368 | 3.618 (1.59–8.24) | 0.002 * |

| I have fresh or cooked vegetables regularly more than once a day | 57 (37) | 61 (51) | 1.827 (1.12–2.97) | 0.010 * | 2.677 (1.29–5.55) | 0.008 * |

| I consume fish regularly (2–3 times/week) | 104 (67) | 74 (62) | 0.822 (0.50–1.35) | 0.260 | ||

| I go more than once a week to a fast-food (hamburger) restaurant | 31 (20) | 28 (24) | 1.241 (0.70–2.21) | 0.279 | ||

| I like pulses and eat them more than once a week | 119 (76) | 87 (73) | 0.845 (0.49–1.46) | 0.322 | ||

| I consume pasta or rice almost every day (5 or more times/week) | 72 (46) | 70 (59) | 1.667 (1.03–2.70) | 0.025 * | ||

| I consume nuts regularly (2–3 times per week) | 78 (50) | 56 (47) | 0.889 (0.55–1.43) | 0.359 | ||

| We use olive oil at home | 153 (98) | 106 (89) | 0.160 (0.40–0.58) | 0.002 * | 0.145 (0.03–0.67) | 0.014 * |

| I eat two yogurts and/or some cheese daily | 129 (83) | 82 (69) | 0.464 (0.26–0.82) | 0.006 * | ||

| I eat sweets and candy several times every day | 42 (27) | 41 (34) | 1.427 (0.85–2.40) | 0.112 | ||

3.3.2. Male Adolescents

| Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do Not Skip Breakfast n (%) | Skip Breakfast n (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value X2 | OR 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Environment | ||||||

| Urban | 95 (48) | 29 (45) | 1.000 | 0.411 | ||

| Non-urban | 103 (52) | 35 (55) | 1.113 (0.63–1.96) | |||

| Monthly household income | ||||||

| Less than EUR 1000 | 15 (8) | 10 (16) | 1.000 | 0.379 | ||

| EUR 1000–EUR 1999 | 72 (36) | 22 (34) | 0.458 (0.18–1.16) | |||

| EUR 2000–EUR 2999 | 53 (27) | 18 (28) | 0.509 (0.20–1.33) | |||

| More than EUR 3000 | 27 (14) | 8 (13) | 0.444(0.14–1.37) | |||

| EQ5D worry/sadness | ||||||

| No problems | 157 (79) | 53 (83) | 1.000 | 0.631 | ||

| Some problems | 37 (19) | 9 (14) | 0.721 (0.33–1.59) | |||

| A lot of problems | 4 (2) | 2 (3) | 1.481 (0.26–8.32) | |||

| EQ5D pain/discomfort | 0 (0) | |||||

| No problems | 174 (88) | 50 (78) | 1.000 | 0.052 | ||

| Some problems | 24 (12) | 13 (20) | 1.885 (0.90–3.97) | |||

| A lot of problems | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | - | |||

| Enjoy physical activity (PA) | ||||||

| None | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.070 | |||

| Little | 8 (4) | 1 (2) | 1.000 | |||

| Somewhat | 24 (12) | 16 (25) | 5.333 (0.61–46.85) | |||

| Quite a bit | 70 (35) | 22 (34) | 2.514 (0.298–21.23) | |||

| Very much | 96 (48) | 25 (39) | 2.083 (0.25–17.44) | |||

| PA recommendations | ||||||

| Does not meet | 32 (16) | 14 (22) | 1.000 | 0.195 | ||

| Meets | 166 (84) | 50 (78) | 0.688 (0.34–1.39) | |||

| Modo desplazamiento | ||||||

| Activo | 121 (61) | 36 (56) | 1.000 | 0.278 | ||

| Motorizado | 76 (38) | 28 (44) | 1.238 (0.70–2.19) | |||

| Screen time | ||||||

| Less than 4 h | 107 (54) | 24 (38) | 1.000 | 0.015 * | ||

| 4 h or more | 91 (46) | 40 (63) | 1.960 (1.10–3.49) | |||

| Screen time recommendations | ||||||

| Less than 2 h/day | 35 (18) | 5 (8) | 1.000 | 0.038 * | ||

| 2 h/day or more | 163 (82) | 59 (92) | 0.395 (0.15–1.06) | |||

| Dinner time | ||||||

| Before 21 pm | 85 (43) | 23 (36) | 1.000 | 0.723 | ||

| Between 21:00 and 21:30 | 57 (29) | 20 (31) | 1.297 (0.65–2.58) | |||

| Between 21:30 and 22:00 | 40 (20) | 13 (20) | 1.201 (0.55–2.61) | |||

| After 22:00 pm | 15 (8) | 7 (11) | 1.725 (0.63–4.73) | |||

| Bedtime | ||||||

| Before 22:00 pm | 38 (19) | 9 (14) | 1.000 | 0.014 * | ||

| Between 22:00 and 23:00 | 83 (42) | 18 (28) | 0.916 (0.38–2.22) | |||

| Between 23:00 and 24:00 | 42 (21) | 12 (19) | 1.206 (0.46–3.18) | |||

| After 24:00 pm | 35 (18) | 23 (36) | 2.775 (1.13–6.80) | |||

| Sleeping hours | ||||||

| Less than 8 h | 59 (30) | 21 (33) | 1.000 | 0.324 | ||

| 8 h or more | 139 (70) | 41 (64) | 0.829 (0.45–1.52) | |||

| BMI (Cole) | ||||||

| Normal weight | 136 (70) | 36 (56) | 1.000 | 0.047 * | 1 | 0.035 * |

| Overweight/obesity | 59 (30) | 27 (42) | 1.729 (0.96–3.10) | 2.185 (1.06–4.52) | ||

| KidMed | ||||||

| High adherence | 78 (39) | 49 (77) | 1.000 | <0.001 * | 1 | <0.001 * |

| Low adherence | 120 (61) | 15 (23) | 0.199 (0.10–0.38) | 0.136 (0.06–0.32) | ||

| Kidmed (1.000 = yes) | ||||||

| I have a dairy product for breakfast | 176 (89) | 38 (59) | 0.183 (0.09–0.36) | 0.001 * | 0.263 (0.12–0.60) | 0.02 * |

| I have cereals or grains for breakfast | 127 (64) | 27 (42) | 0.408 (0.23–0.73) | 0.002 * | ||

| I have commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast | 87 (44) | 23 (36) | 0.716 (0.40–1.28) | 0.163 | 0.413 (0.20–0.88) | 0.022 * |

| I consume a fruit or a fruit juice every day | 116 (59) | 32 (50) | 0.707 (0.40–1.25) | 0.145 | ||

| I have a second fruit everyday | 99 (50) | 22 (34) | 0.524 (0.29–0.94) | 0.020 * | ||

| I have fresh or cooked vegetables regularly once a day | 126 (64) | 33 (52) | 0.608 (0.34–1.08) | 0.059 | ||

| I have fresh or cooked vegetables regularly more than once a day | 79 (40) | 23 (36) | 0.845 (0.47–1.52) | 0.340 | ||

| I consume fish regularly (2–3 times/week) | 121 (61) | 31 (48) | 0.598 (0.34–1.05) | 0.051 | ||

| I go more than once a week to a fast-food (hamburger) restaurant | 46 (23) | 11 (17) | 0.686 (0.33–1.42) | 0.201 | ||

| I like pulses and eat them more than once a week | 153 (77) | 41 (64) | 0.524 (0.29–0.96) | 0.029 * | ||

| I consume pasta or rice almost every day (5 or more times/week) | 115 (58) | 33 (52) | 0.768 (0.44–1.35) | 0.221 | 2.009 (0.94–4.32) | 0.074 |

| I consume nuts regularly (2–3 times per week) | 106 (54) | 34 (53) | 0.984 (0.56–1.73) | 0.534 | ||

| We use olive oil at home | 185 (93) | 53 (83) | 0.339 (0.14–0.80) | 0.014 * | ||

| I eat two yogurts and/or some cheese daily | 152 (77) | 43 (67) | 0.620 (0.33–1.45) | 0.088 | ||

| I eat sweets and candy several times every day | 48 (24) | 13 (20) | 0.797 (0.40–1.59) | 0.321 | 0.462 (0.19–1.12) | 0.086 |

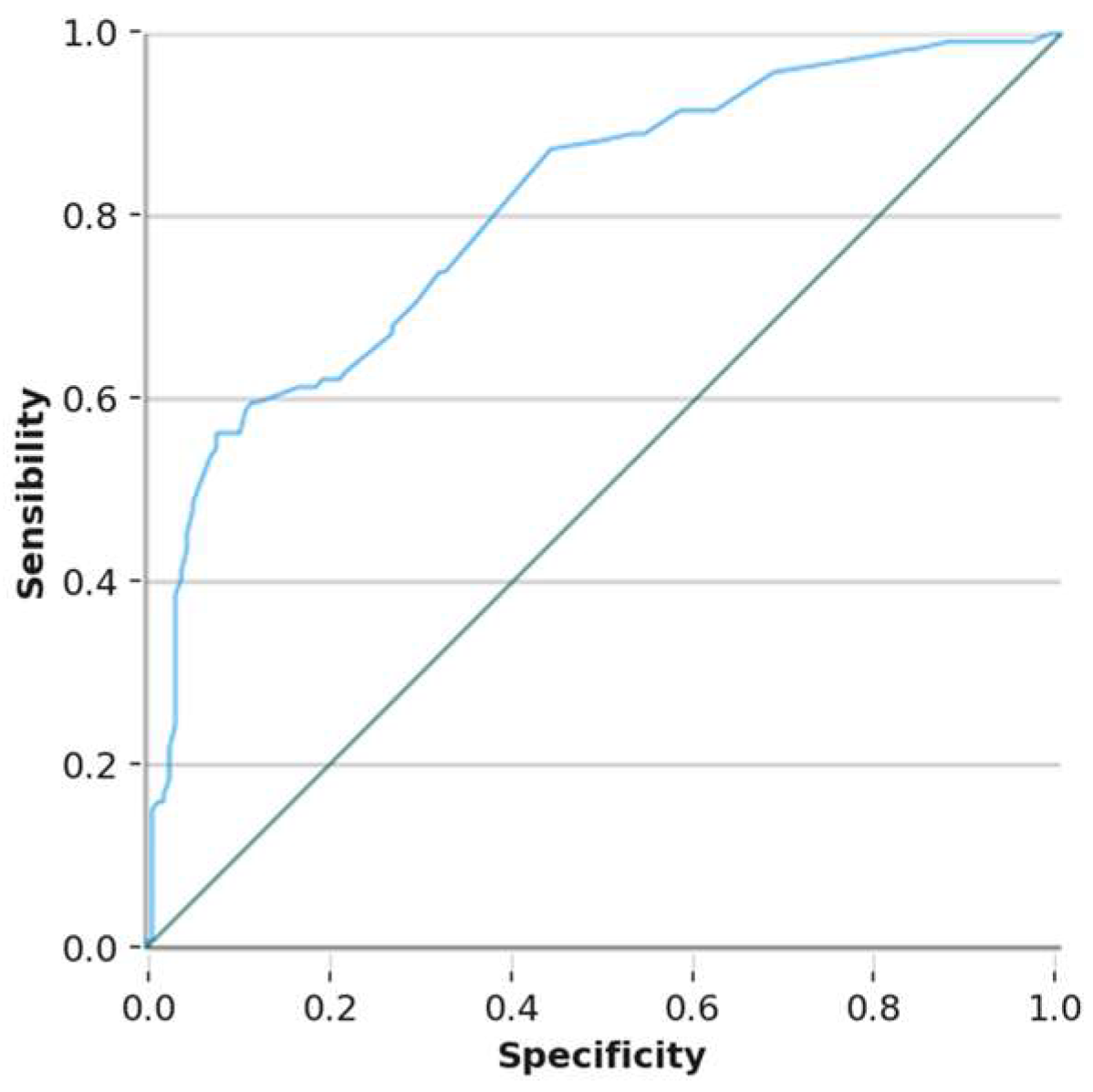

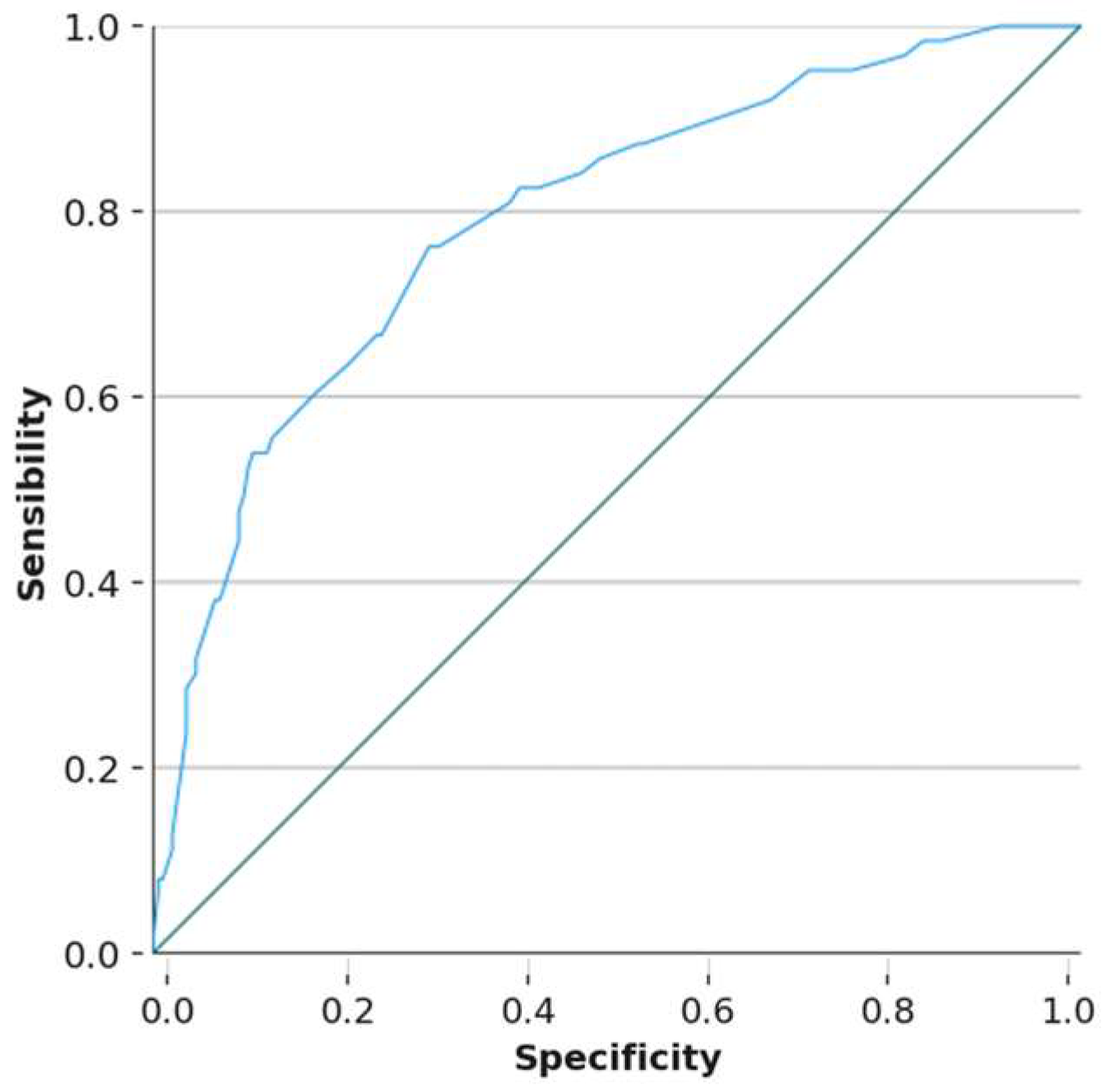

3.4. Predictive Capacity of the Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| ESO | Third-year student (secondary education) |

| PA | Physical activity |

References

- Pollit, E. Does breakfast make a difference in school? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1995, 95, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; García-Hermoso, A. Skipping breakfast and excess weight among young people: The moderator role of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3195–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, A.; Ricotti, R.; Caputo, M.; Solito, A.; Archero, F.; Bellone, S.; Prodam, F. A Systematic Review of the Association of Skipping Breakfast with Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents. What Should We Better Investigate in the Future? Nutrients 2019, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotti, R.; Caputo, M.; Monzani, A.; Pigni, S.; Antoniotti, V.; Bellone, S.; Prodam, F. Breakfast Skipping, Weight, Cardiometabolic Risk, and Nutrition Quality in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled and Intervention Longitudinal Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.A.; Carins, J.E.; Rundle-Thiele, S. A systematic review of interventions to increase breakfast consumption: A socio-cognitive perspective. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3253–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Menezes, L.R.D.; e Souza, R.C.V.; Cardoso, P.C.; dos Santos, L.C. Factors Associated with Dietary Patterns of Schoolchildren: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.R.; Neves, M.E.A.; Gorgulho, B.M.; Souza, A.M.; Nogueira, P.S.; Ferreira, M.G.; Rodrigues, P.R.M. Breakfast skipping and cardiometabolic risk factors in adolescents: Systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 2021, 55, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keats, E.C.; Rappaport, A.I.; Shah, S.; Oh, C.; Jain, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. The Dietary Intake and Practices of Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, S.A.; Bloch, T.D.; Marriage, B.; Shriver, L.H.; Spees, C.K.; Taylor, C.A. Skipping breakfast is associated with lower diet quality in young US children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürbüz, M.; Bayram, H.M.; Kabayel, N.; Türker, Z.S.; Şahin, Ş.; İçer, S. Association between breakfast consumption, breakfast quality, mental health and quality of life in Turkish adolescents: A high school-based cross-sectional study. Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dialektakou, K.D.; Vranas, P.B.M. Breakfast skipping and body mass index among adolescents in Greece: Whether an association exists depends on how breakfast skipping is defined. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, C.; Sánchez-Queija, I.; Camacho, I.; Rivera, F.; Ramos, P. Informe técnico de los resultados obtenidos por el Estudio Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) en España 2022. Ministerio de Sanidad. 2025. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/entornosSaludables/escuela/estudioHBSC/2022/docs/HBSC2022_InformeTecnico.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Elseifi, O.S.; Abdelrahman, D.M.; Mortada, E.M. Effect of a nutritional education intervention on breakfast consumption among preparatory school students in Egypt. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traub, M.; Lauer, R.; Kesztyüs, T.; Wartha, O.; Steinacker, J.M.; Kesztyüs, D.; Briegel, I.; Dreyhaupt, J.; Friedemann, E.M.; Kelso, A.; et al. Skipping breakfast, overconsumption of soft drinks and screen media: Longitudinal analysis of the combined influence on weight development in primary schoolchildren. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, H.; Djalalinia, S.; Sadeghi, O.; Zare Garizi, F.; Asayesh, H.; Payab, M.; Zarei, M.; Qorbani, M. Breakfast consumption and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 1250–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, Q.; Pu, Y.; Guo, M.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, W.; Long, Y.; Xu, Y. Skipping breakfast is associated with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, S.; Ilić, A.; Mišigoj-Duraković, M.; Sorić, M.; Radman, I.; Šatalić, Z. Obesity in Adolescents Who Skip Breakfast Is Not Associated with Physical Activity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhong, J.M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, M.; Gong, W.W.; Pan, J.; Fei, F.R.; Wu, H.B.; Yu, M. Breakfast Consumption and Its Associations with Health-Related Behaviors among School-Aged Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study in Zhejiang Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oellingrath, I.M.; Svendsen, M.V.; Brantsæter, A.L. Eating patterns and overweight in 9- to 10-year-old children in Telemark County, Norway: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 1272–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, L.D.; Rosen, N.J.; Fenton, K.; Au, L.E.; Goldstein, L.H.; Shimada, T. School Breakfast Policy Is Associated with Dietary Intake of Fourth- and Fifth-Grade Students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.M.; Bronner, Y.; Welch, C.; Dewberry-Moore, N.; Paige, D.M. Breakfast and lunch meal skipping patterns among fourth-grade children from selected public schools in urban, suburban, and rural Maryland. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Moraleda, E.; Pinilla-Quintana, I.; Jiménez-Zazo, F.; Martínez-Romero, M.T.; Dorado-Suárez, A.; Romero-Blanco, C.; García-Coll, V.; Cabanillas, E.; Mota-Utanda, C.; Gómez, N.; et al. Protocolo del Proyecto PACOyPACA CLM: (Pedalea y Anda al Cole y Pedalea y Anda a Casa en Castilla-La Mancha). Rev. Iberoam. Cienc. Act. Física Deport. 2023, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas, L.; Ngo, J.; Ortega, R.M.; García, A.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Fernández, P.; Herrador-Colmenero, M.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Castro-Piñero, J.; Molina-García, J.; Queralt, A.; Aznar, S.; Abarca-Sos, A.; González-Cutre, D.; Vidal-Conti, J.; et al. Active commuting to school among 36,781 Spanish children and adolescents: A temporal trend study. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2021, 31, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, A.R.; Carskadon, M.A.; Acebo, C.; Seifer, R.; Fallone, G.; Labyak, S.E.; Martin, J.L. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep 2003, 26, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-López, J.P.; Ruiz, J.R.; Ortega, F.B.; Verloigne, M.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Gottrand, F.; Molnar, D.; Widhalm, K.; Zaccaria, M.; et al. Reliability and validity of a screen time-based sedentary behaviour questionnaire for adolescents: The HELENA study. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 22, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.F.; Homs, C.; Wärnberg, J.; Medrano, M.; Gonzalez-Gross, M.; Gusi, N.; Aznar, S.; Cascales, E.M.; González-Valeiro, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; et al. Study protocol of a population-based cohort investigating Physical Activity, Sedentarism, lifestyles and Obesity in Spanish youth: The PASOS study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of selfchange of smokingT owardanint. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, N.; Badia, X.; Bonsel, G.; Burström, K.; Cavrini, G.; Devlin, N.; Egmar, A.C.; Greiner, W.; Gusi, N.; Herdman, M.; et al. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: A child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, T.P.; Meilstrup, C.; Holstein, B.E.; Rasmussen, M. Fruit and vegetable intake is associated with frequency of breakfast, lunch and evening meal: Cross-sectional study of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Niu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Duo, B.; Effah, C.Y.; Guan, L. The effect of breakfast on childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1222536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Skipping Breakfast and Its Association with Health Risk Behaviour and Mental Health Among University Students in 28 Countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, N.B.; Jebeile, H.; Truby, H.; Garnett, S.P.; Varady, K.A.; Cowell, C.T.; Collins, C.E.; Paxton, S.J.; Gow, M.L.; Brown, J.; et al. Fast track to health—Intermittent energy restriction in adolescents with obesity. A randomised controlled trial study protocol. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Cuccolo, K.; Hallward, L.; Nagata, J.M. Intermittent fasting: Describing engagement and associations with eating disorder behaviors and psychopathology among Canadian adolescents and young adults. Eat. Behav. 2022, 47, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlatt, K.L.; Farbakhsh, K.; Dengel, D.R.; Lytle, L.A. Breakfast and fast food consumption are associated with selected biomarkers in adolescents. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkert, E.C.O.; De Moraes, A.C.F.; Carvalho, H.B.; Manios, Y.; Widhalm, K.; González-Gross, M.; Gutierrez, A.; Kafatos, A.; Censi, L.; De Henauw, S.; et al. Skipping breakfast is associated with adiposity markers especially when sleep time is adequate in adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Ban, D.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-M.; Shin, I.-S.; Kim, S.-W. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with breakfast skipping among high school students. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touitou, Y.; Touitou, D.; Reinberg, A. Disruption of adolescents’ circadian clock: The vicious circle of media use, exposure to light at night, sleep loss and risk behaviors. J. Physiol. Paris 2016, 110, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquius, L.; Aguilar-Martínez, A.; Bosque-Prous, M.; González-Casals, H.; Bach-Faig, A.; Colillas-Malet, E.; Salvador, G.; Espelt, A. Social Inequalities in Breakfast Consumption among Adolescents in Spain: The DESKcohort Project. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, L.K.; Clarke, G.P.; Cade, J.E.; Edwards, K.L. Fast food and obesity: A spatial analysis in a large United Kingdom population of children aged 13–15. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, e77–e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Do Not Skip Breakfast (183) | Skip Breakfast (354) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Media ± SD | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 280 (51) | 156 (44) | 119 (65) | <0.001 * | |

| Male | 267 (49) | 198 (56) | 64 (35) | ||

| Age | 14.81 ± 0.60 | 0.088 | |||

| Enjoy PA | |||||

| None | 8 (1) | 2 (1) | 6 (3) | 0.058 | |

| Little | 18 (3) | 12 (3) | 6 (3) | ||

| Somewhat | 121 (22) | 71 (20) | 46 (25) | ||

| Quite a bit | 197 (36) | 129 (36) | 66 (36) | ||

| Very much | 200 (37) | 140 (40) | 59 (32) | ||

| Screen time | |||||

| Less than 4 h | 287 (53) | 200 (56) | 83 (45) | 0.014 * | |

| 4 h or more | 257 (47) | 154 (44) | 100 (55) | ||

| Screen time recommendations | |||||

| Less than 2 h/day | 453 (83) | 289 (82) | 159 (87) | 0.121 | |

| 2 h/day or more | 91 (17) | 65 (18) | 24 (13) | ||

| Sleeping hours | 8.16 ± 0.96 | ||||

| Less than 8 h | 178 (33) | 108 (31) | 70 (39) | 0.047 * | |

| 8 h or more | 355 (67) | 246 (69) | 109 (61) | ||

| Monthly household income | |||||

| Less than EUR 1000 | 14 (3) | 36 (12) | 22 (14) | 0.573 | |

| EUR 1000-EUR 1999 | 13 (2) | 139 (45) | 81 (50) | ||

| EUR 2000-EUR 2999 | 38 (7) | 81 (26) | 38 (24) | ||

| More than EUR 3000 | 133 (25) | 50 (16) | 20 (12) | ||

| BMI (Cole) | 21.83 ± 4.26 | ||||

| Normal weight | 378 (70) | 253 (72) | 118 (65) | 0.068 | |

| Overweight/obesity | 163 (30) | 96 (28) | 64 (35) | ||

| KidMed | 6.23 ± 2.72 | ||||

| High adherence | 271 (50) | 211 (60) | 60 (33) | <0.001 * | |

| Low adherence | 270 (50) | 143 (40) | 123 (67) | ||

| Environment | |||||

| Urban | 264 (44) | 163 (46) | 79 (43) | 0.573 | |

| Non-urban | 334 (56) | 191 (54) | 104 (57) | ||

| Total n (%) | Male n (%) | Female n (%) | Chi2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast 0 days | 57 (11) | 18 (7) | 39 (14) | <0.001 * |

| Breakfast 1 day | 19 (4) | 6 (2) | 13 (5) | |

| Breakfast 2 days | 34 (6) | 11 (4) | 23 (8) | |

| Breakfast 3 days | 42 (8) | 13 (5) | 29 (11) | |

| Breakfast 4 days | 31 (6) | 16 (6) | 15 (5) | |

| Breakfast 5 days | 354 (66) | 198 (76) | 156 (57) | |

| I do not have time for breakfast | 175 (33) | 67 (26) | 108 (39) | <0.001 * |

| I do not like breakfast | 81 (15) | 35 (13) | 46 (17) | 0.166 |

| I forget to have breakfast | 100 (19) | 37 (14) | 63 (23) | 0.006 * |

| I am not hungry | 211 (39) | 75 (29) | 136 (49) | <0.001 * |

| I have a dairy product for breakfast | 409 (76) | 214 (82) | 195 (71) | 0.002 * |

| I have cereals or grains for breakfast | 295 (55) | 154 (59) | 141 (51) | 0.048 * |

| I have commercially baked goods or pastries for breakfast | 211 (39) | 110 (42) | 101 (37) | 0.123 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Blanco, C.; Martín-Moraleda, E.; Pinilla-Quintana, I.; Dorado-Suárez, A.; Jiménez-Marín, A.; Cabanillas-Cruz, E.; García-Coll, V.; Martínez-Romero, M.T.; Aznar, S. Why Do Adolescents Skip Breakfast? A Study on the Mediterranean Diet and Risk Factors. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121948

Romero-Blanco C, Martín-Moraleda E, Pinilla-Quintana I, Dorado-Suárez A, Jiménez-Marín A, Cabanillas-Cruz E, García-Coll V, Martínez-Romero MT, Aznar S. Why Do Adolescents Skip Breakfast? A Study on the Mediterranean Diet and Risk Factors. Nutrients. 2025; 17(12):1948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121948

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Blanco, Cristina, Evelyn Martín-Moraleda, Iván Pinilla-Quintana, Alberto Dorado-Suárez, Alejandro Jiménez-Marín, Esther Cabanillas-Cruz, Virginia García-Coll, María Teresa Martínez-Romero, and Susana Aznar. 2025. "Why Do Adolescents Skip Breakfast? A Study on the Mediterranean Diet and Risk Factors" Nutrients 17, no. 12: 1948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121948

APA StyleRomero-Blanco, C., Martín-Moraleda, E., Pinilla-Quintana, I., Dorado-Suárez, A., Jiménez-Marín, A., Cabanillas-Cruz, E., García-Coll, V., Martínez-Romero, M. T., & Aznar, S. (2025). Why Do Adolescents Skip Breakfast? A Study on the Mediterranean Diet and Risk Factors. Nutrients, 17(12), 1948. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121948