Effects of Oral Nutrition Supplementation with or Without Multi-Domain Intervention Program on Cognitive Function and Overall Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

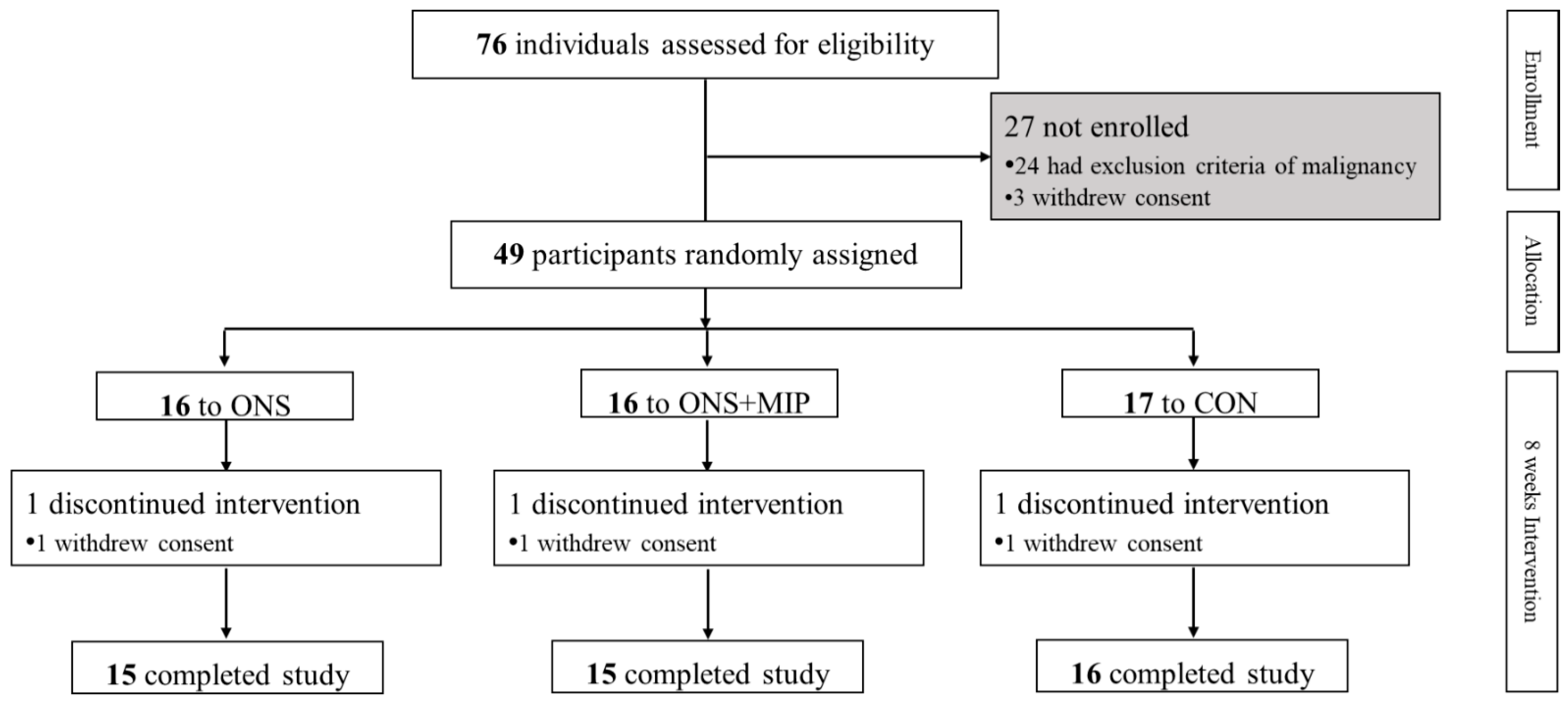

2.1. Participants and Duration

2.2. Study Design

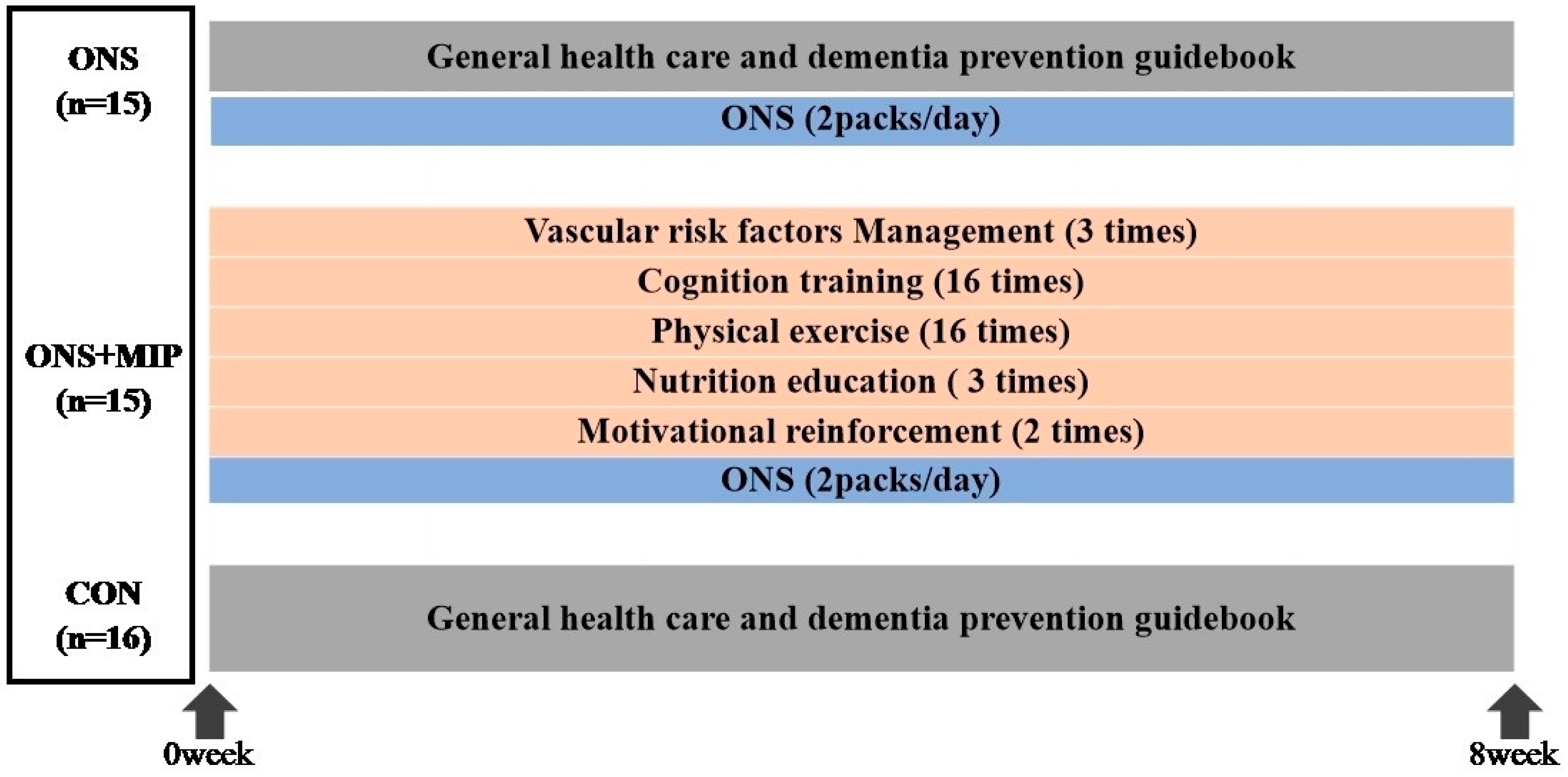

2.2.1. Intervention

2.2.2. Adherence

2.3. Outcome Measurements

2.3.1. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) Total Scores

2.3.2. Nutritional Assessments

2.3.3. Body Composition and Physical Performance Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Adherence Rates to the Multi-Domain Intervention Program and Oral Nutrition Supplement

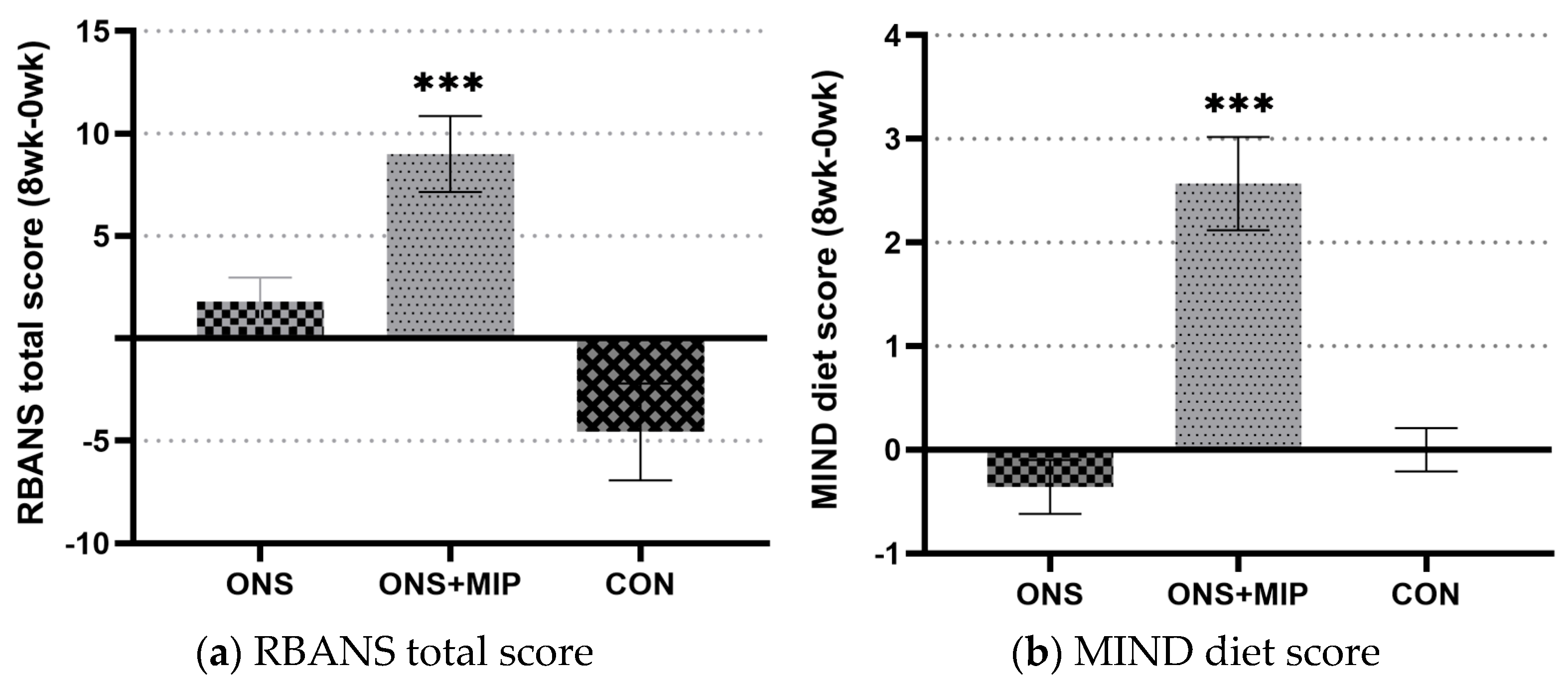

3.3. The RBANS Score

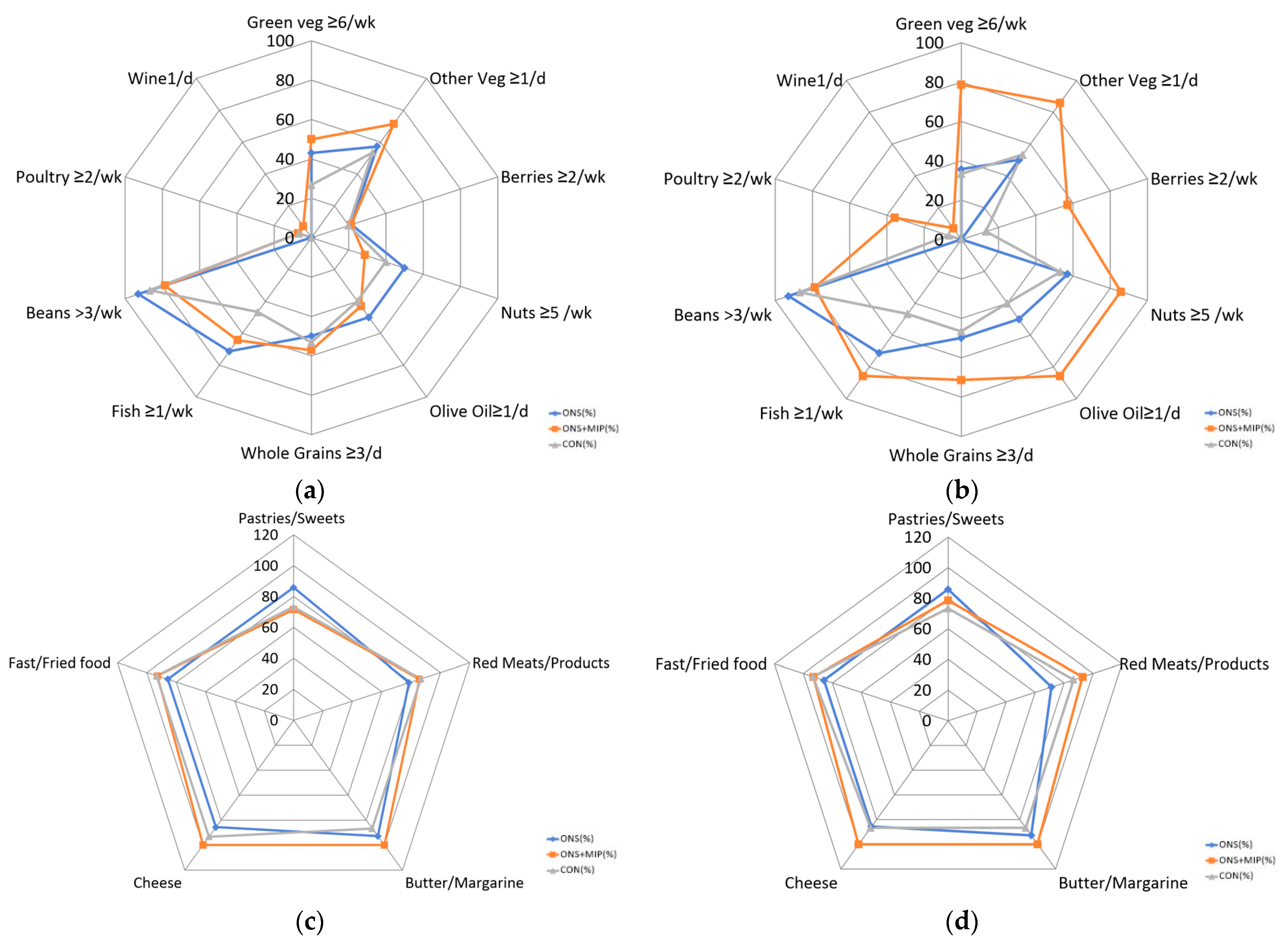

3.4. The Mediterranean-Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet Score

3.5. The Nutrition Quotient for the Elderly (NQ-E)

3.6. Body Composition and Physical Performance

3.7. Subgroup Analysis of RBANS, Short Physical Performance Battery, and NQ-E Change Scores According to Changes in the MIND Diet Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OMS | Oral Nutrition Supplement |

| MIP | Multi-Domain Intervention Program |

| RBANS | Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status |

| MIND diet | Mediterranean-Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Intervention for Neuro-Degenerative Delay |

| SUPERBRAIN study | the South Korea study to prevent cognitive impairment and protect BRAIN health through lifestyle intervention in at-risk older people study |

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

References

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheets-Dementia. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korean Dementia Observatory 2022; Final Report; Central Dementia Centre: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023.

- Frisoni, G.B.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Altomare, D.; Carrera, E.; Barkhof, F.; Berkhof, J.; Delrieu, J.; Dubois, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Nordberg, A. Precision prevention of Alzheimer’s and other dementias: Anticipating future needs in the control of risk factors and implementation of disease-modifying therapies. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020, 16, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; You, J.; Cui, H.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, W.; Liu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, Q. The n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation improved the cognitive function in the Chinese elderly with mild cognitive impairment: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, F.; Wu, T.; Zhao, J.; Han, F.; Marseglia, A.; Liu, H.; Huang, G. Effects of 6-month folic acid supplementation on cognitive function and blood biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial in China. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenacchi, T.; Bertoldin, T.; Farina, C.; Fiori, M.; Crepaldi, G.; Azzini, C.; Girardello, R.; Bagozzi, B.; Garuti, R.; Vivaldi, P. Cognitive decline in the elderly: A double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study on efficacy of phosphatidylserine administration. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1993, 5, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.C.; Kamphuis, P.J.; Leurgans, S.; Swinkels, S.H.; Sadowsky, C.H.; Bongers, A.; Rappaport, S.A.; Quinn, J.F.; Wieggers, R.L.; Scheltens, P. The S-Connect study: Results from a randomized, controlled trial of Souvenaid in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2013, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salva, A.; Andrieu, S.; Fernandez, E.; Schiffrin, E.; Moulin, J.; Decarli, B.; Rojano-i-Luque, X.; Guigoz, Y.; Vellas, B.; Group, T.N. Health and nutrition promotion program for patients with dementia (NutriAlz): Cluster randomized trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calapai, G.; Bonina, F.; Bonina, A.; Rizza, L.; Mannucci, C.; Arcoraci, V.; Laganà, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Pollicino, C.; Inferrera, S. A randomized, double-blinded, clinical trial on effects of a Vitis vinifera extract on cognitive function in healthy older adults. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Twisk, J.W.; Blesa, R.; Scarpini, E.; Von Arnim, C.A.; Bongers, A.; Harrison, J.; Swinkels, S.H.; Stam, C.J.; De Waal, H. Efficacy of Souvenaid in mild Alzheimer’s disease: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 31, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivipelto, M.; Mangialasche, F.; Ngandu, T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.Y.; Hong, C.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, Y.K.; Na, H.R.; Song, H.-S.; Kim, B.C.; Park, K.W.; Park, H.K.; Choi, M. Facility-based and home-based multidomain interventions including cognitive training, exercise, diet, vascular risk management, and motivation for older adults: A randomized controlled feasibility trial. Aging 2021, 13, 15898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randolph, C.; Tierney, M.C.; Mohr, E.; Chase, T.N. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): Preliminary clinical validity. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998, 20, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, M.J.; Kwak, T.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Kang, M.H.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, H.R.; Kwon, S.; Hwang, J.Y.; Choi, Y.S. Development of NQ-E, Nutrition Quotient for Korean elderly: Item selection and validation of factor structure. J. Nutr. Health 2018, 51, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Simonsick, E.M.; Salive, M.E.; Wallace, R.B. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutis, K.; Willan, A. Intention-to-treat and per-protocol analysis. Cmaj 2011, 183, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Hyun, Y.-S.; Kim, H.-S. Nutritional status of Korean elderly with dementia in a long-term care facility in Hongseong. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeuchi, T.; Kanda, M.; Kitamura, H.; Morikawa, F.; Toru, S.; Nishimura, C.; Kasuga, K.; Tokutake, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kuroha, Y. Decreased circulating branched-chain amino acids are associated with development of Alzheimer’s disease in elderly individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1040476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dhana, K.; Huang, Y.; Huang, L.; Tao, Y.; Liu, X.; Van Lent, D.M.; Zheng, Y.; Ascherio, A.; Willett, W. Association of the Mediterranean dietary approaches to stop hypertension intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diet with the risk of dementia. JAMA Psychiatry 2023, 80, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ONS (n = 15) | ONS+MIP (n = 15) | CON (n = 16) | p Value (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 5 (33.3%) | 9 (60.0%) | 12 (75.0%) | 0.066 (2) |

| Age (year) * | 76.8 ± 5.0 | 74.3 ± 5.5 | 76.0 ± 6.8 | 0.483 |

| Education (year) * | 11.4 ± 4.5 | 9.6 ± 3.6 | 8.5 ± 4.6 | 0.177 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 23.2 ± 2.2 | 23.0 ± 4.1 | 23.8 ± 1.9 | 0.729 |

| RBANS * | 74.7 ± 11.5 | 78.6 ± 16.9 | 79.5 ± 15.9 | 0.641 |

| SPPB * | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 9.3 ± 2.1 | 10.0 ± 1.9 | 0.468 |

| NQ-E * | 62.0 ± 9.1 | 56.5 ± 11.6 | 60.9 ± 9.9 | 0.312 |

| NQ-E | Group | Baseline | Week 8 | p-Value (1) | Δ8 w-0 w | p-Value (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Scores | ONS (n = 15) | 63.2 ± 8.06 | 62.8 ± 7.82 | 0.615 | −0.5 ± 3.24 | 0.002 ** (4) | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 55.7 ± 11.50 | 62.0 ± 11.22 | 0.018 * | 6.3 ± 8.71 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 61.2 ± 10.13 | 61.1 ± 11.01 | 0.889 (3) | −0.0 ± 2.93 | |||

| Sub-domain | Balance | ONS (n = 15) | 56.0 ± 20.38 | 53.9 ± 20.95 | 0.498 | −2.1 ± 11.40 | 0.527 |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 45.0 ± 22.74 | 52.6 ± 22.73 | 0.490 | 2.6 ± 13.84 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 54.8 ± 13.17 | 54.5 ± 13.26 | 0.650 | 0.7 ± 7.32 | |||

| Diversity | ONS (n = 15) | 49.0 ± 16.88 | 48.0 ± 16.40 | 0.344 (3) | −1.0 ± 3.36 | 0.053 | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 50.2 ± 12.90 | 52.4 ± 13.59 | 0.100 | 2.2 ± 4.61 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 54.8 ± 13.17 | 54.5 ± 13.26 | 0.650 | −0.3 ± 2.25 | |||

| Moderation | ONS (n = 15) | 77.9 ± 15.96 | 80.1 ± 12.40 | 0.264 | 2.2 ± 7.00 | 0.001 ** (5) | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 60.0 ± 13.05 | 75.8 ± 15.76 | 0.005 ** | 15.7 ± 17.33 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 66.6 ± 21.68 | 67.3 ± 20.74 | 0.599 | 0.7 ± 4.84 | |||

| Dietary behavior | ONS (n = 15) | 62.8 ± 10.65 | 61.3 ± 11.40 | 0.165 | −1.6 ± 3.99 | 0.035 * | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 58.9 ± 14.30 | 60.8 ± 13.80 | 0.100 | 2.0 ± 4.15 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 60.7 ± 14.28 | 59.60 ± 14.74 | 0.192 | −1.1 ± 3.15 | |||

| Physical Status | Group | Baseline | Week 8 | p-Value (1) | Δ8 w–0 w | p-Value (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body composition | BMI (kg/m2) | ONS (n = 15) | 23.0 ± 2.14 | 23.2 ± 2.10 | 0.424 | 0.2 ± 0.78 | 0.914 |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 23.0 ± 4.06 | 23.1 ± 4.17 | 0.454 | 0.2 ± 0.74 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 23.8 ± 1.91 | 23.8 ± 1.69 | 0.773 | 0.1 ± 0.80 | |||

| Body fat (%) | ONS (n = 15) | 29.1 ± 7.19 | 29.7 ± 7.49 | 0.422 | 0.6 ± 2.55 | 0.620 | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 33.6 ± 9.66 | 33.4 ± 10.22 | 0.598 | −0.3 ± 1.91 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 34.2 ± 6.31 | 34.1 ± 6.18 | 0.924 | −0.1 ± 2.56 | |||

| SMM (kg) | ONS (n = 15) | 22.2 ± 4.68 | 22.5 ± 4.80 | 0.355 | 0.2 ± 0.95 | 0.839 | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 20.2 ± 3.74 | 20.4 ± 3.58 | 0.397 | 0.1 ± 0.56 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 20.1 ± 4.93 | 20.2 ± 4.72 | 0.641 (3) | 0.1 ± 0.81 | |||

| VF (level) | ONS (n = 15) | 7.4 ± 2.31 | 7.8 ± 2.67 | 0.139 | 0.4 ± 1.02 | 0.629 | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 9.5 ± 4.47 | 9.5 ± 4.47 | 1.000 | 0.0 ± 1.13 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 9.3 ± 2.79 | 9.3 ± 2.59 | 1.000 | 0.0 ± 1.79 | |||

| Physical performance | Left grip (kg) | ONS (n = 15) | 22.0 ± 7.42 | 23.1 ± 8.13 | 0.162 | 1.2 ± 2.89 | 0.396 |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 19.3 ± 7.17 | 20.7 ± 6.83 | 0.039 * | 1.4 ± 2.22 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 18.4 ± 8.24 | 18.6 ± 7.71 | 0.774 | 0.2 ± 2.45 | |||

| Right grip (kg) | ONS (n = 15) | 23.9 ± 7.28 | 24.2 ± 8.06 | 0.685 | 0.3 ± 2.39 | 0.313 | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 20.7 ± 7.10 | 21.9 ± 6.83 | 0.219 | 1.2 ± 3.44 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 19.6 ± 7.66 | 19.3 ± 6.85 | 0.544 | −0.4 ± 2.33 | |||

| Sit and stand | ONS (n = 15) | 12.5 ± 3.18 | 12.6 ± 5.20 | 0.888 | 0.1 ± 3.72 | 0.035 * | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 11.9 ± 3.73 | 13.9 ± 3.53 | 0.002 ** | 1.9 ± 1.86 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 13.1 ± 4.39 | 12.6 ± 4.27 | 0.185 (3) | −0.4 ± 1.31 | |||

| SPPB (total score) | ONS (n = 15) | 10.1 ± 1.29 | 9.6 ± 1.34 | 0.131 | −0.5 ± 1.16 | <0.000 *** | |

| ONS+MIP (n = 15) | 9.3 ± 2.16 | 10.9 ± 1.34 | 0.014 * | 1.4 ± 1.78 | |||

| CON (n = 16) | 10.0 ± 1.90 | 9.1 ± 2.38 | 0.007 ** (3) | −0.9 ± 1.00 | |||

| Δ8 w–0 w | Group A (1) (n = 19) | Group B (2) (n = 24) | p Value (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBANS change scores | 6.0 ± 7.71 | −0.7 ± 9.26 | 0.017 * |

| SPPB change scores | 0.7 ± 2.02 | −0.7 ± 0.95 | 0.008 ** |

| NQ-E change scores | 4.5 ± 7.98 | −0.2 ± 3.41 | 0.026 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, H.-J.; Lee, E.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Moon, S.-Y.; Jeong, J.-H.; Park, Y.-K. Effects of Oral Nutrition Supplementation with or Without Multi-Domain Intervention Program on Cognitive Function and Overall Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111941

Kang H-J, Lee E-H, Choi S-H, Moon S-Y, Jeong J-H, Park Y-K. Effects of Oral Nutrition Supplementation with or Without Multi-Domain Intervention Program on Cognitive Function and Overall Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111941

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Hae-Jin, Eun-Hye Lee, Seong-Hye Choi, So-Young Moon, Jee-Hyang Jeong, and Yoo-Kyoung Park. 2025. "Effects of Oral Nutrition Supplementation with or Without Multi-Domain Intervention Program on Cognitive Function and Overall Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111941

APA StyleKang, H.-J., Lee, E.-H., Choi, S.-H., Moon, S.-Y., Jeong, J.-H., & Park, Y.-K. (2025). Effects of Oral Nutrition Supplementation with or Without Multi-Domain Intervention Program on Cognitive Function and Overall Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 17(11), 1941. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111941