Feeding Difficulties in Children with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases Identified by a Brazilian Portuguese Validated Screening Tool

Abstract

1. Introduction

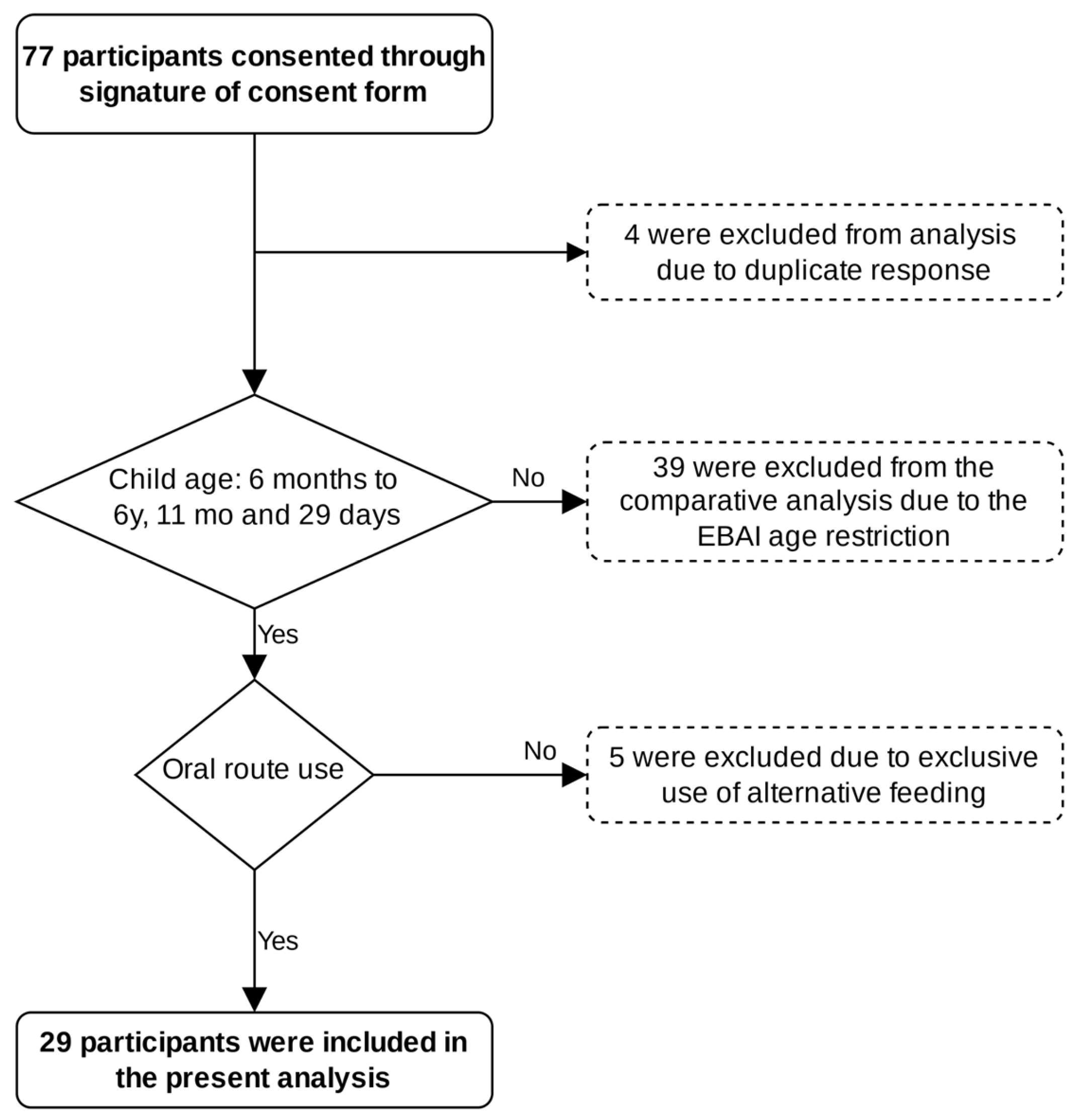

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABGlico | Associação Brasileira de Glicogenoses |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| EBAI | Brazilian Scale of Infant Feeding |

| EEPa | Parental Stress Scale |

| GSD | Hepatic glycogen storage disease |

| G-tube | Gastrostomy |

| HMIPV-IRB | Hospital Materno Infantil Presidente Vargas- |

| MCT | Medium-chain triglycerides |

| NE | Naso-enteral tube |

| NG | Nasogastric tube |

| UCCS | Uncooked cornstarch |

References

- dos Santos, B.B.; Nalin, T.; Grokoski, K.C.; Perry, I.D.S.; Refosco, L.F.; Vairo, F.P.; Souza, C.F.M.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Nutritional status and body composition in patients with hepatic glycogen storage diseases treated with uncooked cornstarch—A controlled study. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2017, 5, 2326409817733014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Pontin, J.; Thompson, S. Dietary management of the ketogenic glycogen storage diseases. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2016, 4, e160021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.A.; Weinstein, D.A. Glycogen storage diseases: Diagnosis, treatment and outcome. Transl. Sci. Rare Dis. 2016, 1, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, P.; Hochuli, M. Hepatic glycogen storage disorders: What have we learned in recent years? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2015, 18, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannah, W.B.; Derks, T.G.; Drumm, M.L.; Grünert, S.C.; Kishnani, P.S.; Vissing, J. Glycogen storage diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2023, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massese, M.; Tagliaferri, F.; Dionisi-Vici, C.; Maiorana, A. Glycogen storage diseases with liver involvement: A literature review of GSD type 0, IV, VI, IX and XI. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishnani, P.S.; Austin, S.L.; Abdenur, J.E.; Arn, P.; Bali, D.S.; Boney, A.; Chung, W.K.; Dagli, A.I.; Dale, D.; Koeberl, D.; et al. Diagnosis and management of glycogen storage disease type I: A practice guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, K.M.; Ferrecchia, I.; Dahlberg, K.; Dambska, M.; Ryan, P.T.; Weinstein, D.A. Dietary management of the glycogen storage diseases: Evolution of treatment and ongoing controversies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K. Dietary dilemmas in the management of glycogen storage disease type I. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011, 34, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.L.; de Souza, C.F.; Schuler-Faccini, L.; Refosco, L.; Epifanio, M.; Nalin, T.; Vieira, S.M.; Schwartz, I.V. Glycogen storage disease type I: Clinical and laboratory profile. J. Pediatr. 2014, 90, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.T.; Bento dos Santos, B.; Nalin, T.; Colonetti, K.; Farret Refosco, L.; FM de Souza, C.; Spritzer, P.M.; Poloni, S.; Hack-Mendes, R.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Bone Mineral Density in Patients with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, V.C.L.; de Oliveira, B.M.; dos Santos, B.B.; Sperb-Ludwig, F.; Refosco, L.F.; Nalin, T.; Derks, T.G.J.; de Souza, C.F.M.; Schwartz, I.V.D. A triple-blinded crossover study to evaluate the short-term safety of sweet manioc starch for the treatment of glycogen storage disease type Ia. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, M.T.; Lima, M.L. Who’s eating what with me?: Indirect social influence on ambivalent food consumption. Psicol. Reflex. Crit. 2013, 26, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowa, M.; Boyer, M.; Green, J.; Pendyal, S.; Saavedra, H. Nutrition Management in Children Less than 5 Years of Age with Glycogen Storage Disease Type I: Survey Results. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Venema, A.; Peeks, F.; Veen, M.d.B.d.; de Boer, F.; Fokkert-Wilts, M.J.; Lubout, C.M.A.; Huskens, B.; Dumont, E.; Mulkens, S.; Derks, T.G.J. A retrospective study of eating and psychosocial problems in patients with hepatic glycogen storage diseases and idiopathic ketotic hypoglycemia: Towards a standard set of patient-reported outcome measures. JIMD Rep. 2022, 63, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, H.I. Evidências de Validade dos Instrumentos de Rastreio para Dificuldades Alimentares Pediátricas: Uma Revisão Sistemática. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, A.T.; Fiorito, L.M.; Francis, L.A.; Birch, L.L. ‘Finish your soup’: Counterproductive effects of pressuring children to eat on intake and affect. Appetite 2006, 46, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.J.; Haycraft, E. Parental body dissatisfaction and controlling child feeding practices: A prospective study of Australian parent-child dyads. Eat. Behav. 2019, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dow, A. Individual Case Study: The SOS Approach to Feeding; College of Health Care Sciences—Occupational Therapy Department: Boynton Beach, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Toomey, K.; Ross, E. SOS approach to feeding. Dysphagia 2011, 20, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, D.C.; Johanson, N. A family-centered approach to feeding disorders in children (Birth to 5 years). Dysphagia 2013, 22, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goday, P.S.; Huh, S.Y.; Silverman, A.; Lukens, C.T.; Dodrill, P.; Cohen, S.S.; Delaney, A.L.; Feuling, M.B.; Noel, R.J.; Gisel, E.; et al. Pediatric feeding disorder consensus definition and conceptual framework. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, P.B. Adaptação Transcultural e Validação de Escala Montreal Children’s Hospital Scale. Doctoral Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, C.C. Dificuldade Alimentar, Distúrbio Miofuncional Orofacial e Sentidos Químicos em Pacientes com Glicogenose Hepática. Doctoral Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, C.C.; Tonon, T.; Nalin, T.; Refosco, L.F.; Souza, C.F.M.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Feeding difficulties and orofacial myofunctional disorder in patients with hepatic glycogen storage diseases. JIMD Rep. 2019, 45, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.; Kuczynski, L.; Haycraft, E.; Breen, A.; Haines, J. Time to re-think picky eating?: A relational approach to understanding picky eating. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.F.V.; Sangrador, C.O.; Giner, C.P.; Hernández, J.S. Psychological and social impact on parents of children with feeding difficulties. An Pediatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 97, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, A.H.; Erato, G.; Goday, P. The relationship between chronic pediatric feeding disorders and caregiver stress. J. Child Health Care 2021, 25, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Wang, L.; Tang, X.; Wu, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y. Association between caregivers’ anxiety and depression symptoms and feeding difficulties of preschool children: A cross-sectional study in rural China. Arch. Pédiatr. 2020, 27, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simione, M.; Harshman, S.; Cooper-Vince, C.E.; Daigle, K.; Sorbo, J.; Kuhlthau, K.; Fiechtner, L. Examining health conditions, impairments, and quality of life for pediatric feeding disorders. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.J.; Gulotta, C.; Masler, E.A.; Laud, R.B. Caregiver stress and outcomes of children with pediatric feeding disorders treated in an intensive interdisciplinary program. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 33, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, M.; Martel, C.; Porporino, M.; Zygmuntowicz, C. The Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale: A brief bilingual screening tool for identifying feeding problems. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 16, 147.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.; Faro, A. Diferenças por sexo, adaptação e validação da Escala de Estresse Parental. Aval. Psicol. 2017, 16, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, S.; Worona, L.; Consuelo, A. Nutritional therapy for glycogen storage diseases. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2008, 47 (Suppl. S1), S15–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, H.; Heary, C.; Kelly, C. Fussy eating behaviours: Response patterns in families of school-aged children. Appetite 2019, 136, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhage, C.L.; Gillebaart, M.; Veek, S.M.C.; van der Vereijken, C.M.J.L. The relation between family meals and health of infants and toddlers: A review. Appetite 2018, 127, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.E.; Norris, M.L.; Obeid, N.; Fu, M.; Weinstangel, H.; Sampson, M. Systematic review of the effects of family meal frequency on psychosocial outcomes in youth. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, e96–e106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weiss-Salinas, D.; Williams, N. Sensory defensiveness: A theory of its effect on breastfeeding. J. Hum. Lact. 2001, 17, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvério, C.C.; Sant’Anna, T.P.; Oliveira, M.F. Ocorrência de dificuldade alimentar em crianças com mielomeningocele. Rev. CEFAC 2005, 7, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- de Miranda, V.S.G.; Flach, K. Aspectos emocionais na aversão alimentar em pacientes pediátricos: Interface entre a fonoaudiologia e a psicologia. Psicol. Estud. 2019, 24, e45247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.H.; Joung, Y.S.; Choe, Y.H.; Kim, E.H.; Kwon, J.Y. Sensory processing difficulties in toddlers with nonorganic failure-to-thrive and feeding problems. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérat, C.-M.; Roda, C.; Brassier, A.; Bouchereau, J.; Wicker, C.; Servais, A.; Dubois, S.; Assoun, M.; Belloche, C.; Barbier, V.; et al. Enteral tube feeding in patients receiving dietary treatment for metabolic diseases: A retrospective analysis in a large French cohort. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 26, 100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciuto, A.; Baird, R.; Sant’Anna, A. A retrospective review of enteral nutrition support practices at a tertiary pediatric hospital: A comparison of prolonged nasogastric and gastrostomy tube feeding. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scortegagna, M.L. Perfil de Vitaminas do Complexo B em Pacientes com Glicogenoses Hepáticas e seus Possíveis Determinantes. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, B.L. Glicogenose Tipo I: Caracterização Clínico-Laboratorial de Pacientes Atendidos em um Ambulatório de Referência em Erros Inatos do Metabolismo. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.M.; Roux, S.; Naidoo, N.T.R.; Venter, D.J. Food choice of tactile defensive children. Nutrition 2005, 21, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.C.; Maximino, P.; Machado, R.H.V.; Bozzini, A.B.; Ribeiro, L.W.; Fisberg, M. Delayed development of feeding skills in children with feeding difficulties—Cross-sectional study in a Brazilian reference center. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, C.C.C. Adesão ao Tratamento de Pacientes com Glicogenose Hepática Tipo 1 Acompanhados em um Serviço de Referência Para Distúrbios Metabólicos. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Simione, M.; Dartley, A.N.; Cooper-Vince, C.; Martin, V.; Hartnick, C.; Taveras, E.M.; Fiechtner, L. Family-centered outcomes that matter most to parents: A pediatric feeding disorders qualitative study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 71, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormack, J.L.; Rowell, K.; Moreland, H.; Wong, G.; Berry, J.; Responsive Feeding Therapy: A Novel, Value-Driven Treatment Approach to Pediatric Avoidant Eating. SSRN 2024. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4928126 (accessed on 9 May 2025). [CrossRef]

| Variables | n = 29 |

|---|---|

| Age (months)—Mean ± SD [range] | 49.7 ± 19.9 (14–79) |

| Gender—n (%) | |

| Male | 19 (65.5) |

| Female | 10 (34.5) |

| GSD Type—n (%) | |

| Ia | 15 (51.7) |

| Ib | 5 (17.2) |

| III | 2 (6.9) |

| VI | 1 (3.4) |

| IX | 2 (6.9) |

| Unknown | 4 (13.8) |

| Family Income (in minimum wages)—n (%) | |

| <1 | 10 (34.5) |

| 1 to 2 | 4 (13.8) |

| 2 to 3 | 7 (24.1) |

| 3 to 5 | 3 (10.3) |

| 5 to 10 | 1 (3.4) |

| >10 | 4 (13.8) |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescribed diet | Foods + UCCS | 19 | 65.5 |

| Lactose-free formula + UCCS | 10 | 34.5 | |

| Feeding method | Exclusive oral | 22 | 75.9 |

| Oral + alternative feeding method | 7 | 24.1 | |

| Alternative feeding method | Gastrostomy | 6 | 20.7 |

| Nasogastric or nasoenteral tube | 1 | 3.4 | |

| Place of meals | At the table | 19 | 65.5 |

| Other (living room, bedroom, kitchen) | 10 | 34.5 | |

| Family meals | Yes | 19 | 65.5 |

| No | 3 | 10.3 | |

| Sometimes | 7 | 24.2 | |

| Nausea or discomfort when looking at the food | 15 | 51.7 | |

| Nausea or discomfort when touching the food | 15 | 51.7 | |

| Nausea or discomfort related to the smell of the food | 18 | 62 | |

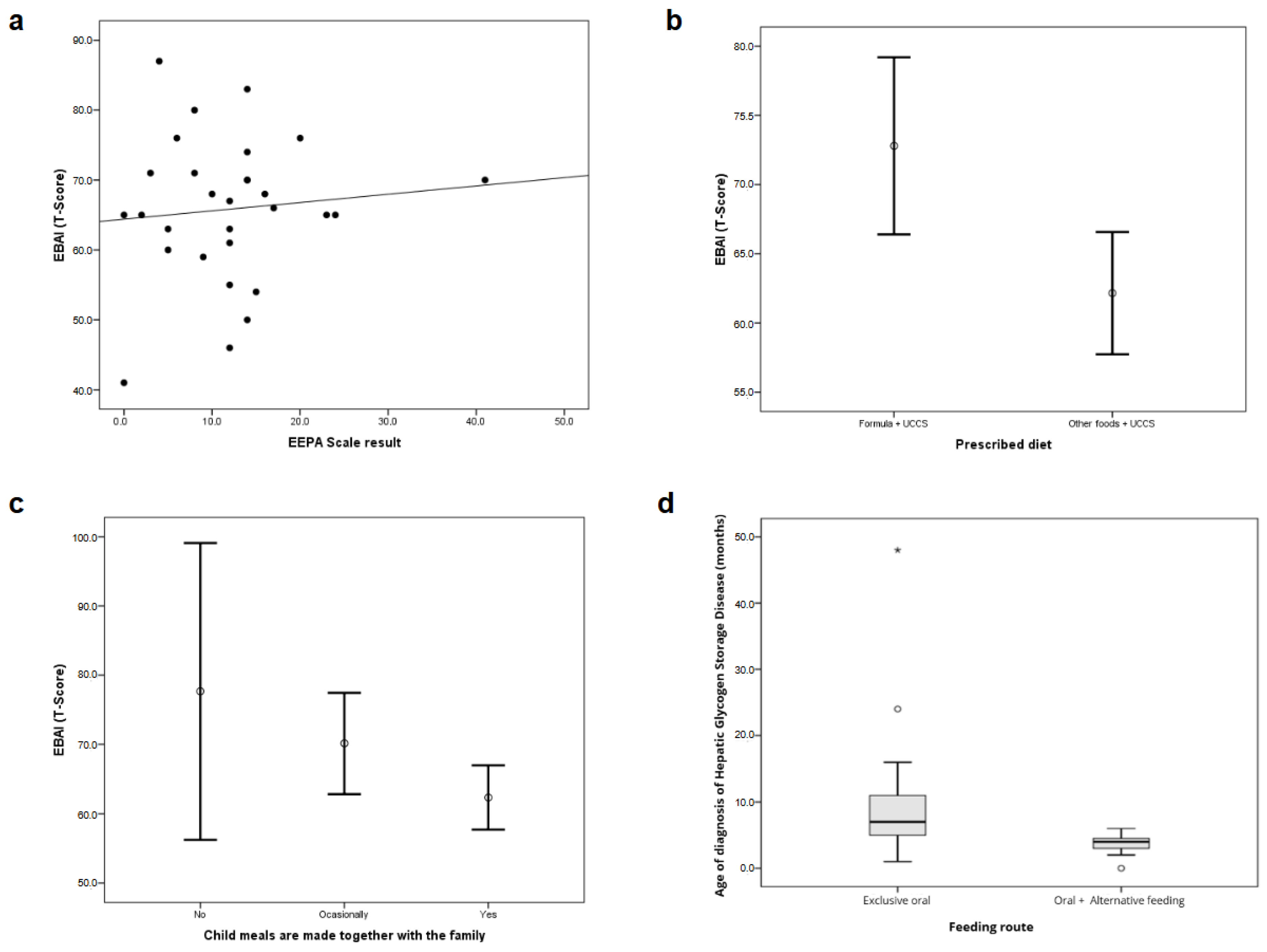

| EBAI Results (T-Score) | EEPA Results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | p | Median (P25–P75) | p | ||

| Child biological sex | Female | 71.1 | 9.2 | 0.043 * | 10.5 (5.5–18) | 0.982 |

| Male | 63.1 | 10.0 | 12 (5–14) | |||

| Family income (in minimum wage) | <1 | 67.2 | 13.3 | 0.940 | 14 (11–16) | 0.059 |

| 1 to 2 | 67.8 | 10.4 | 13 (7–21) | |||

| 2 to 3 | 64.3 | 10.6 | 3 (0–12) | |||

| 3 to 5 | 60.7 | 5.9 | 15 (5–23) | |||

| 5 to 10 | 70.0 | 0 | 41 (41–41) | |||

| >10 | 66.0 | 7.7 | 9.5 (7–12) | |||

| Prescribed diet | Only lactose-free formula + MCT oil | 72.8 | 8.9 | 0.006 * | 8.5 (6–14) | 0.211 |

| Foods + UCCS | 62.2 | 9.2 | 12 (5–17) | |||

| Feeding method | Oral + alternative feeding method | 68.7 | 9.6 | 0.405 | 14 (8–20) | 0.304 |

| Exclusive oral | 64.9 | 10.6 | 12 (5–14) | |||

| Alternative feeding method | Gastrostomy | 69.3 | 10.4 | 0.716 | 13 (7–16) | 0.286 |

| NG/NE | 65 | 0.0 | 24 (24–24) | |||

| Place of the meals | At the table | 64.5 | 6.9 | 0.467 | 12 (6–14) | 0.839 |

| Others | 68.3 | 15.0 | 13 (3–21) | |||

| Family meals | Yes | 62.4 | 9.6 | 0.019 * | 12 (6–14) | 0.558 |

| Sometimes | 70.1 | 7.9 | 10 (2–23) | |||

| No | 77.7 | 8.6 | 20 (4–41) | |||

| Nausea or discomfort from the smell of the food | Yes | 69.5 | 10.0 | 0.011 * | 11 (5–17) | 0.774 |

| No | 59.8 | 7.9 | 12 (9–14) | |||

| Nausea or discomfort when looking at the food | Yes | 71.6 | 7.1 | 0.001 * | 12 (5–17) | 0.621 |

| No | 59.6 | 9.7 | 12 (6–14) | |||

| Nausea or discomfort when touching the food | Yes | 70.8 | 8.2 | 0.005 * | 12 (5–17) | 0.621 |

| No | 60.5 | 9.8 | 12 (6–14) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sartor, B.C.P.; de Oliveira, B.M.; Teruya, K.I.; Farret, L.R.; Tonon, T.; Scortegagna, M.L.; Diniz, P.B.; de Souza, C.F.M. Feeding Difficulties in Children with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases Identified by a Brazilian Portuguese Validated Screening Tool. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111758

Sartor BCP, de Oliveira BM, Teruya KI, Farret LR, Tonon T, Scortegagna ML, Diniz PB, de Souza CFM. Feeding Difficulties in Children with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases Identified by a Brazilian Portuguese Validated Screening Tool. Nutrients. 2025; 17(11):1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111758

Chicago/Turabian StyleSartor, Bárbara Cristina Pezzi, Bibiana Mello de Oliveira, Katia Irie Teruya, Lilia Ramos Farret, Tássia Tonon, Mariana Lima Scortegagna, Patrícia Barcellos Diniz, and Carolina Fischinger Moura de Souza. 2025. "Feeding Difficulties in Children with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases Identified by a Brazilian Portuguese Validated Screening Tool" Nutrients 17, no. 11: 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111758

APA StyleSartor, B. C. P., de Oliveira, B. M., Teruya, K. I., Farret, L. R., Tonon, T., Scortegagna, M. L., Diniz, P. B., & de Souza, C. F. M. (2025). Feeding Difficulties in Children with Hepatic Glycogen Storage Diseases Identified by a Brazilian Portuguese Validated Screening Tool. Nutrients, 17(11), 1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17111758