Eating Disorder Symptoms and Energy Deficiency Awareness in Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts: Evidence of a Knowledge Gap

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Measures

2.2.1. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

2.2.2. Knowledge of Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

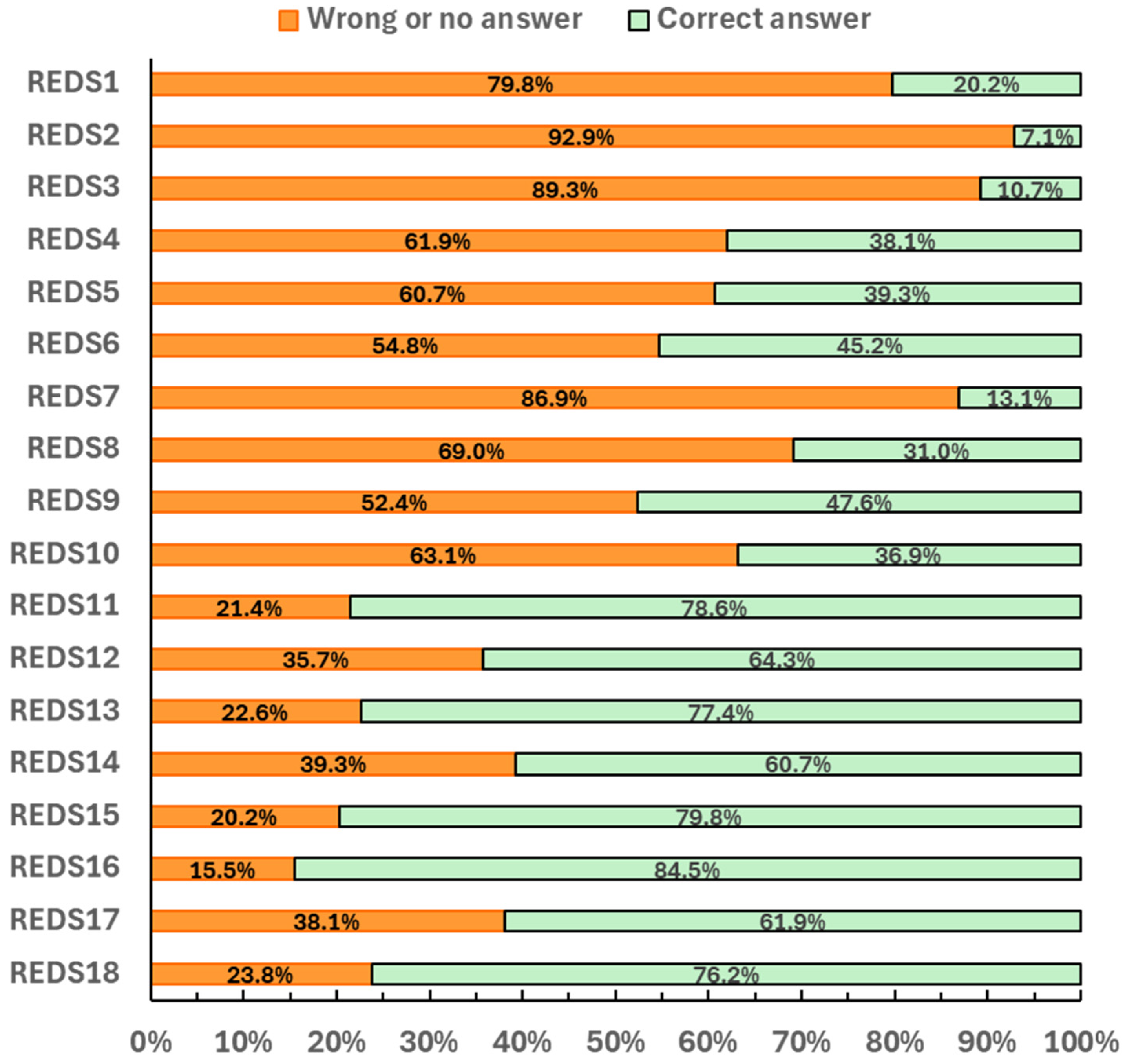

3.2. RelativeED-S Knowledge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RED-S | Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome |

| EDE-Q | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire |

| LEA | Low energy availability |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M. Treatment of eating disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatr. Rev. 2006, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D. Measurement of eating disorder psychopathology. In Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Comprehensive Handbook, 2nd ed.; Fairburn, C.G., Brownell, K.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy, M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Bailey, D.M.; Burke, L.M.; Constantini, N.; Hackney, A.C.; Heikura, I.A.; Melin, A.; Pensgaard, A.M.; Stellingwerff, T.; et al. International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs). Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelidi, A.M.; Stefanakis, K.; Chou, S.H.; Valenzuela-Vallejo, L.; Dipla, K.; Boutari, C.; Ntoskas, K.; Tokmakidis, P.; Kokkinos, A.; Goulis, D.G.; et al. Relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs): Endocrine manifestations, pathophysiology and treatments. Endocr. Rev. 2024, 45, 676–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J. Eating disorders, energy intake, training volume, and menstrual function in high-level modern rhythmic gymnasts. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1996, 6, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, G.; Holmes, R.A.; Mu, Z.; Yang, P.; Lin, Z.; Nakai, Y. Disordered eating in Japanese and Chinese female runners, rhythmic gymnasts, and gymnasts. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Petrie, T.A. Prevalence of disordered eating and pathogenic weight control behaviors among NCAA Division I female collegiate gymnasts and swimmers. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2012, 83, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, A.P.; Oudejans, R.R.D.; Bakker, F.C. Dieting and body image in aesthetic sports: A comparison of Dutch female gymnasts and non-aesthetic sport participants. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Durme, K.; Goossens, L.; Braet, C. Adolescent aesthetic athletes: A group at risk for eating pathology? Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontele, I.; Vassilakou, T.; Donti, O. Weight pressures and eating disorder symptoms among adolescent female gymnasts of different performance levels in Greece. Children 2022, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, C.L.; Hainline, B.; Aron, C.M.; Baron, D.; Baum, A.L.; Bindra, A.; Budgett, R.; Campriani, N.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Currie, A.; et al. Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 667–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, S.; McLean, N. Elite athletes: Effects of the pressure to be thin. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2002, 5, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Torstveit, M.K. Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2004, 14, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, G.M.; Soares Ede, A.; Ribeiro, B.G. Are female athletes at increased risk for disordered eating and its complications? Appetite 2010, 55, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, N.H.; Schneider, M.; Wood, C. Preventing obesity and eating disorders in adolescents. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Z.J.; Rodriguez, P.; Wright, D.R.; Austin, S.B.; Long, M.W. Estimation of eating disorders prevalence by age and associations with mortality in a simulated nationally representative US cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malina, R.M.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Armstrong, N.; Beunen, G.P.; Caine, D.; Daly, R.M.; Lewis, R.D.; Rogol, A.D.; Russell, K. Role of intensive training in the growth and maturation of artistic gymnasts. Sports Med. 2013, 43, 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donti, O.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Kritikou, M.; Donti, A.; Theodorakou, K. The relative contribution of physical fitness to the technical execution score in youth rhythmic gymnastics. J. Hum. Kinet. 2016, 51, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbrow, B.; McCormack, J.; Burke, L.M.; Cox, G.R.; Fallon, K.; Hislop, M.; Logan, R.; Marino, N.; Sawyer, S.M.; Shaw, G.; et al. Sports Dietitians Australia position statement: Sports nutrition for the adolescent athlete. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, M.E.; Borkan, M.; Quatromoni, P. Sports nutrition advice for adolescent athletes: A time to focus on food. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2015, 9, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.O.A.; Calitri, R.; Bloodworth, A.; McNamee, M.J. Understanding eating disorders in elite gymnastics: Ethical and conceptual challenges. Clin. Sports Med. 2016, 35, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Fields, J.; Magee, M.K.; Kerksick, C.M.; Jones, M.T. Contributing factors to low energy availability in female athletes: A narrative review of energy availability, training demands, nutrition barriers, body image, and disordered eating. Nutrients 2022, 14, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenqvist, T.B.; Melin, A.K.; Torstveit, M.K. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs) indicators in male adolescent endurance athletes: A 3-year longitudinal study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torstveit, M.K.; Ackerman, K.E.; Constantini, N.; Holtzman, B.; Koehler, K.; Mountjoy, M.L.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Melin, A. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs): A narrative review by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on REDs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M.K. The Female Athlete Triad in Norwegian Elite Athletes and Non-Athletic Controls: Identification and Prevalence of Disordered Eating, Menstrual Dysfunction, and Osteoporosis. Doctoral Dissertation, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, Norway, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, L.M.; Lundy, B.; Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Melin, A.K. Pitfalls of conducting and interpreting estimates of energy availability in free-living athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2018, 28, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fostervold-Mathisen, T.; Ackland, T.; Burke, L.M.; Constantini, N.; Haudum, J.; Macnaughton, L.S.; Meyer, N.L.; Mountjoy, M.; Slater, G.; Sungot-Borgen, J. Best practice recommendations for body composition considerations in sport to reduce health and performance risks: A critical review, original survey and expert opinion by a subgroup of the IOC consensus on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; Fairburn, C.G., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 309–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pliatskidou, S.; Samakouri, M.; Kalamara, E.; Papageorgiou, E.; Koutrouvi, K.; Goulemtzakis, C.; Nikolaou, E.; Livaditis, M. Validity of the Greek Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire 6.0 (EDE-Q-6.0) among Greek adolescents. Psychiatriki 2015, 26, 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, N.N.; Brown, R.C.; Black, K.E. The development and validation of a questionnaire to assess relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S) knowledge. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2022, 25, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, P.J. The Eating Disorder Examination. In Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment And treatment, 12th ed.; Fairburn, C.G., Wilson, G.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Pliatskidou, S.; Samakouri, M.; Kalamara, E.; Goulemtsakis, C.; Koutrouvi, K.; Papageorgiou, E.; Livadites, M. Reliability of the Greek version of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in a sample of adolescent students. Psychiatriki 2012, 23, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Bratland-Sanda, S.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Eating disorders in athletes: Overview of prevalence, risk factors, and recommendations for prevention and treatment. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donti, O.; Donti, A.; Gaspari, V.; Pleksida, P.; Psychountaki, M. Are they too perfect to eat healthy? Association between eating disorder symptoms and perfectionism in adolescent rhythmic gymnasts. Eat. Behav. 2021, 41, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrgios, I.; Papageorgiou, V.; Kotanidou, E.; Kokka, P.; Kleisarchaki, A.; Mouzaki, K.; Tsara, I.; Efstratiou, E.; Haidich, A.-B.; Galli-Tsinopoulou, A. Eating Disorders in Greek Adolescents: Frequency and Characteristics. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual ESPE, Barcelone, Spain, 1–3 October 2015; Volume 84. [Google Scholar]

- Bacciotti, S.; Baxter-Jones, A.; Gaya, A.; Maia, J. The physique of elite female artistic gymnasts: A systematic review. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 58, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claessens, A.L.; Lefevre, J.; Beunen, G.; Malina, R.M. The contribution of anthropometric characteristics to performance scores in elite female gymnasts. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 1999, 39, 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin, A.P.K.; Oudejans, R.R.D.; Bakker, F.C.; Woertman, L. Contextual body image and athletes’ disordered eating: The contribution of athletic body image to disordered eating in high-performance women athletes. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2011, 19, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donti, O.; Theodorakou, K.; Kambiotis, S.; Donti, A. Self-esteem and trait anxiety in girls practicing competitive and recreational gymnastics. Sci. Gymnast. J. 2012, 4, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsdóttir, H.; Sigurðardóttir, P.; Jónsdóttir, S.; Þorsteinsdóttir, G.; Saavedra, J. Body image concern and eating disorder symptoms among elite Icelandic athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, J.D.; Taylor, C.B.; Telch, M.J.; Saylor, K.E.; Maron, D.J.; Robinson, T.N. Self-induced vomiting and laxative and diuretic use among teenagers. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1986, 255, 1447–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.W.; McKeag, D.B.; Hough, D.O.; Curley, V. Pathogenic weight-control behavior in female athletes. Physician Sportsmed. 1986, 14, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mond, J.M.; Hay, P.J.; Rodgers, B.; Owen, C.; Mitchell, J.E. Correlates of self-induced vomiting and laxative misuse in a community sample of women. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006, 194, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserfurth, P.; Palmowski, J.; Hahn, A.; Krüger, K. Reasons for and consequences of low energy availability in female and male athletes: Social environment, adaptations, and prevention. Sports Med. Open 2020, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M.K.; Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Lichtenstein, M.B.; Stenqvist, T.B.; Melin, A.K. Exercise dependence, eating disorder symptoms, and biomarkers of relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S) among male endurance athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, M.; Villa-Vicente, J.G.; Seco-Calvo, J.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Collado, P.S. Body composition, dietary intake, and the risk of low energy availability in elite-level competitive rhythmic gymnasts. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logue, D.M.; Madigan, S.M.; Melin, A.; Delahunt, E.; Heinen, M.; Donnell, S.-J.M.; Corish, C.A. Low energy availability in athletes 2020: An updated narrative review of prevalence, risk, within-day energy balance, knowledge, and impact on sports performance. Nutrients 2020, 12, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the female athlete triad—Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman, K.E.; Sokoloff, N.C.; Maffazioli, G.D.N.; Clarke, H.; Lee, H.; Misra, M. Fractures in relation to menstrual status and bone parameters in young athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.A.; Bradshaw, E.J.; Ball, N.B.; Pease, D.L.; Spratford, W. Injury epidemiology and risk factors in competitive artistic gymnasts: A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosi, M.; Maslyanskaya, S.; Dodson, N.A.; Coupey, S.M. The female athlete triad: A comparison of knowledge and risk in adolescent and young adult figure skaters, dancers, and runners. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019, 32, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torstveit, M.K.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Participation in leanness sports but not training volume is associated with menstrual dysfunction: A national survey of 1276 elite athletes and controls. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Vandoni, M.; Bianchi, A.; Pirazzi, A.; Tiranini, L.; Baldassarre, P.; Diotti, M.; Cavallo, C.; Nappi, R.E.; Zuccotti, G. Menstrual dysfunction in adolescent female athletes. Sports 2024, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, R.T.; Thompson, R.A.; Rose, J.S. Body mass index and athletic performance in elite female gymnasts. J. Sport Behav. 1996, 19, 338–346. [Google Scholar]

| High Level Gymnasts (n = 39) | Low Level Gymnasts (n = 45) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 14 (14, 15) | 14 (13, 15) | 0.061 |

| Training experience (y) | 8 (6, 8) | 6 (3, 8) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 159 (157, 162) | 160 (156, 163) | 0.815 |

| Body mass (Kg) | 47 (44, 50) | 50 (47, 55) | 0.019 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 18.7 (17.7, 19.7) | 20.1 (18.4, 21.4) | 0.006 |

| High Level Gymnasts (n = 39) | Low Level Gymnasts (n = 45) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q total score | 2.07 (1.12, 3.13) | 1.17 (0.44, 1.73) | <0.001 |

| Subscales | |||

| Restrain | 1.40 (0.60, 3.60) | 0.60 (0.20, 1.70) | 0.014 |

| Eating Concern | 1.20 (0.40, 2.60) | 0.60 (0.20, 1.20) | 0.009 |

| Weight Concern | 2.00 (1.60, 4.20) | 1.00 (0.40, 2.20) | <0.001 |

| Shape concern | 2.38 (1.63, 3.75) | 1.25 (0.50, 2.31) | <0.001 |

| RED-S total score | 8.74 ± 3.04 | 8.71 ± 2.98 | 0.961 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donti, A.; Maraki, M.I.; Psychountaki, M.; Donti, O. Eating Disorder Symptoms and Energy Deficiency Awareness in Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts: Evidence of a Knowledge Gap. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101699

Donti A, Maraki MI, Psychountaki M, Donti O. Eating Disorder Symptoms and Energy Deficiency Awareness in Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts: Evidence of a Knowledge Gap. Nutrients. 2025; 17(10):1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101699

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonti, Anastasia, Maria I. Maraki, Maria Psychountaki, and Olyvia Donti. 2025. "Eating Disorder Symptoms and Energy Deficiency Awareness in Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts: Evidence of a Knowledge Gap" Nutrients 17, no. 10: 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101699

APA StyleDonti, A., Maraki, M. I., Psychountaki, M., & Donti, O. (2025). Eating Disorder Symptoms and Energy Deficiency Awareness in Adolescent Artistic Gymnasts: Evidence of a Knowledge Gap. Nutrients, 17(10), 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101699