Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Process

2.2. Research Questionnaire and Data Collection Procedures

2.3. Measurements and BMI Classification

2.4. Statistical Analysis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Population Covered by This Study

- Zimowit: greatest diversity, presence of cases of obesity I and II, high percentage of overweight and obese people (22 people in total);

- Rzeszów: moderate diversity, predominance of overweight (10 people) and normal weight, presence of obesity I and II;

- Tyczyn: healthiest weight profile—no obesity, predominance of normal body weight (55%), limited number of cases of underweight and overweight.

3.2. Dietary Behaviour and Physical Activity Related to Weight Control

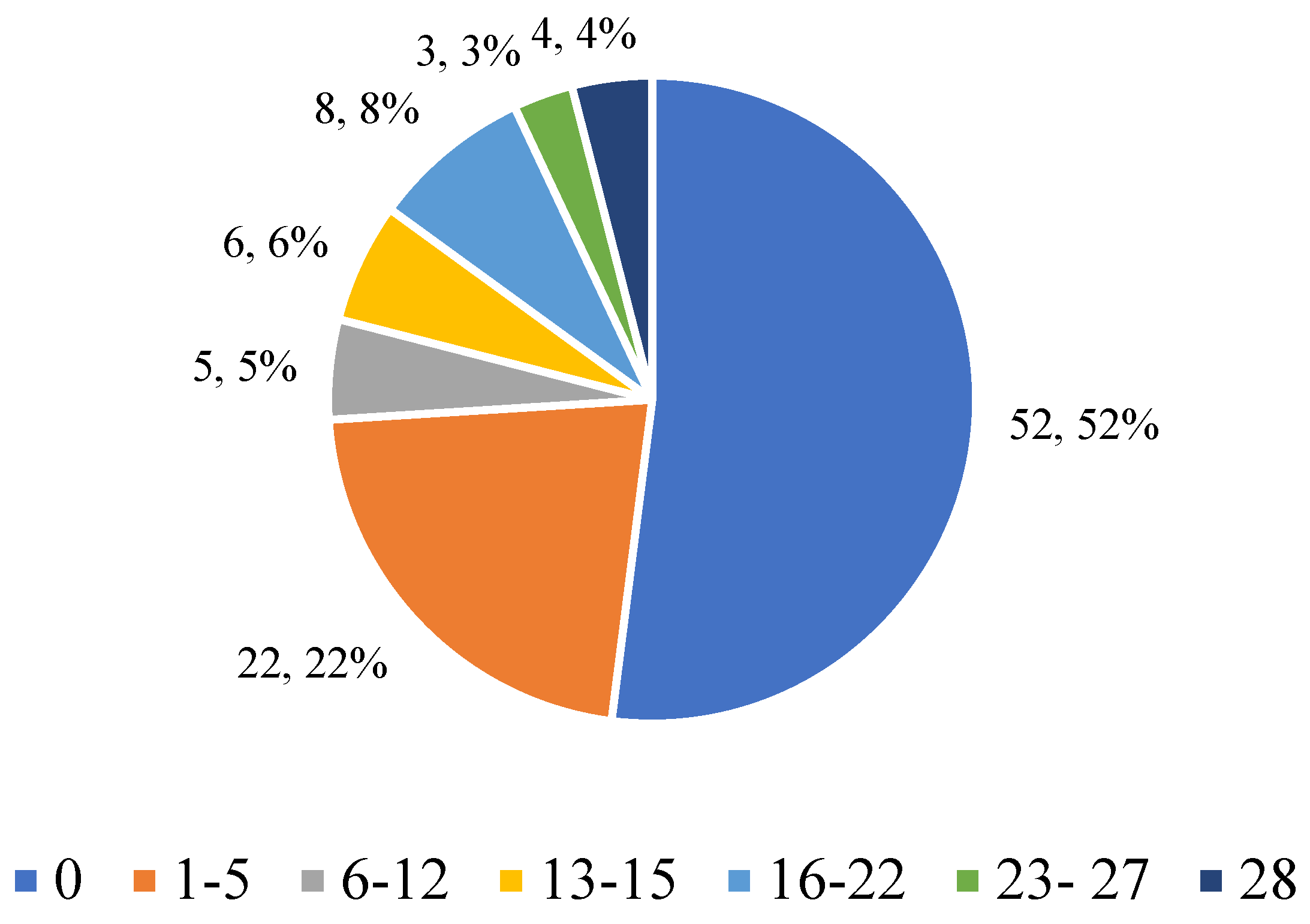

3.2.1. Eating in Secret

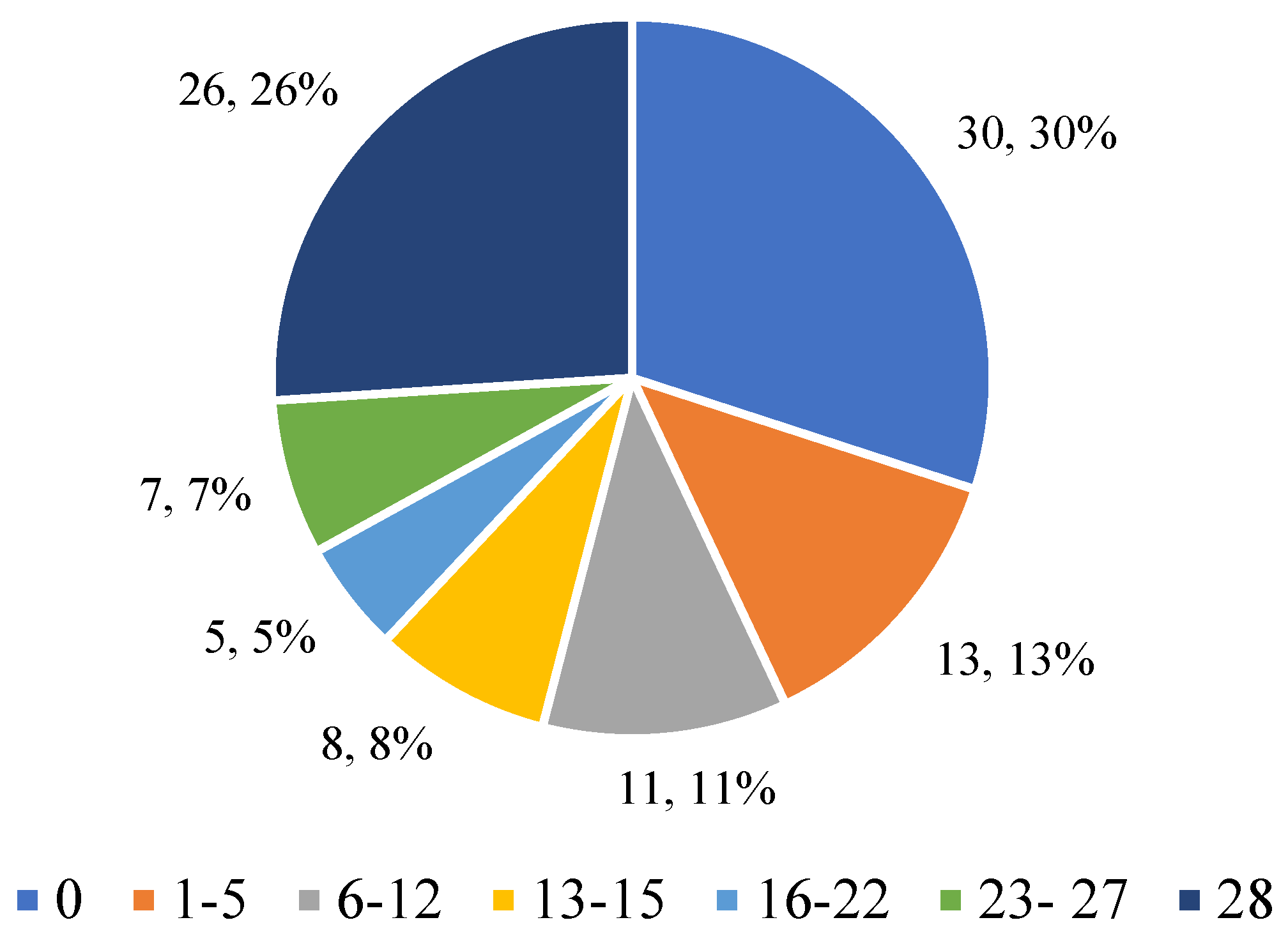

3.2.2. The Desire to Have a Flat Stomach

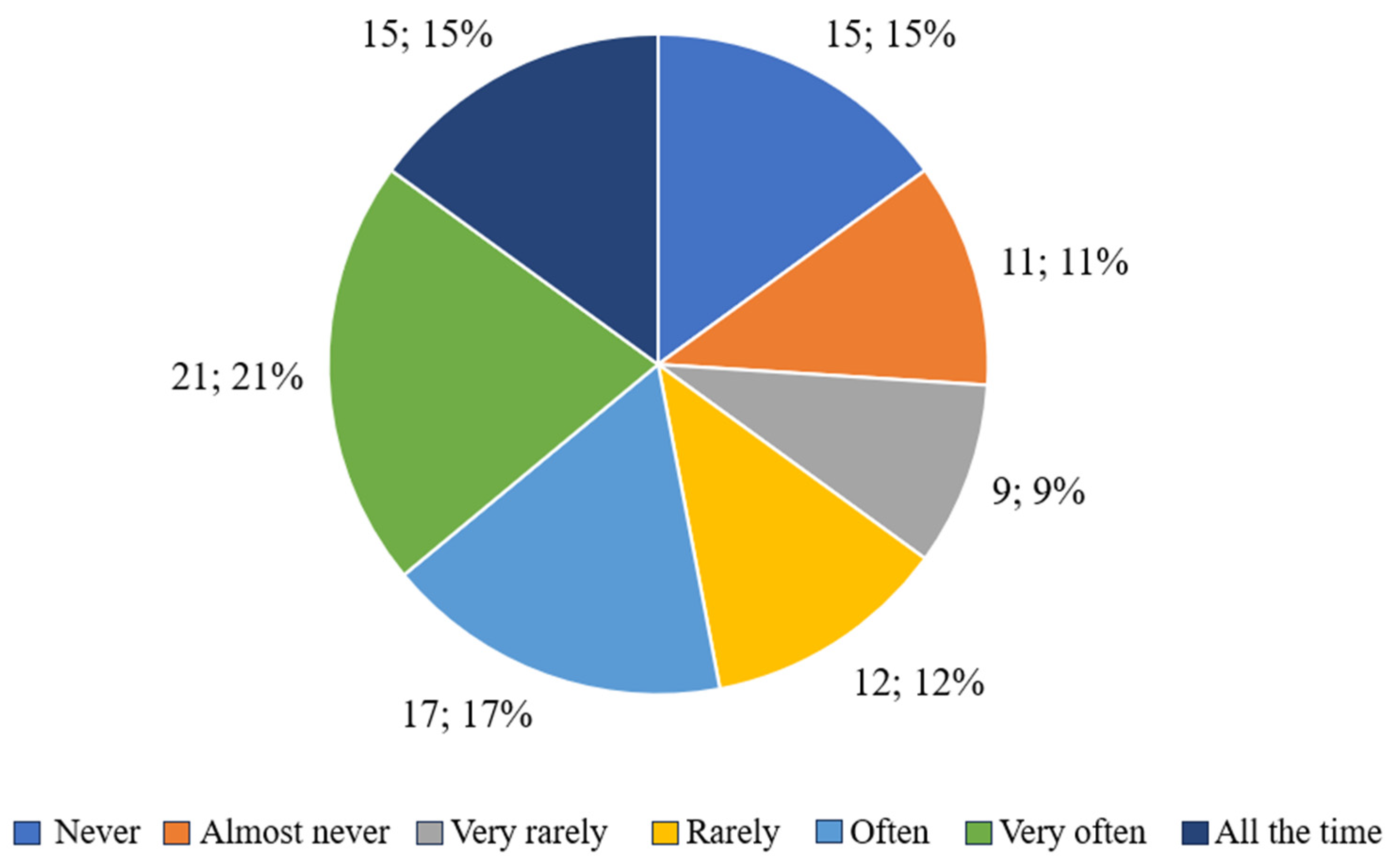

3.2.3. The Influence of Body Shape on Self-Perception

3.2.4. Dissatisfaction with One’s Body

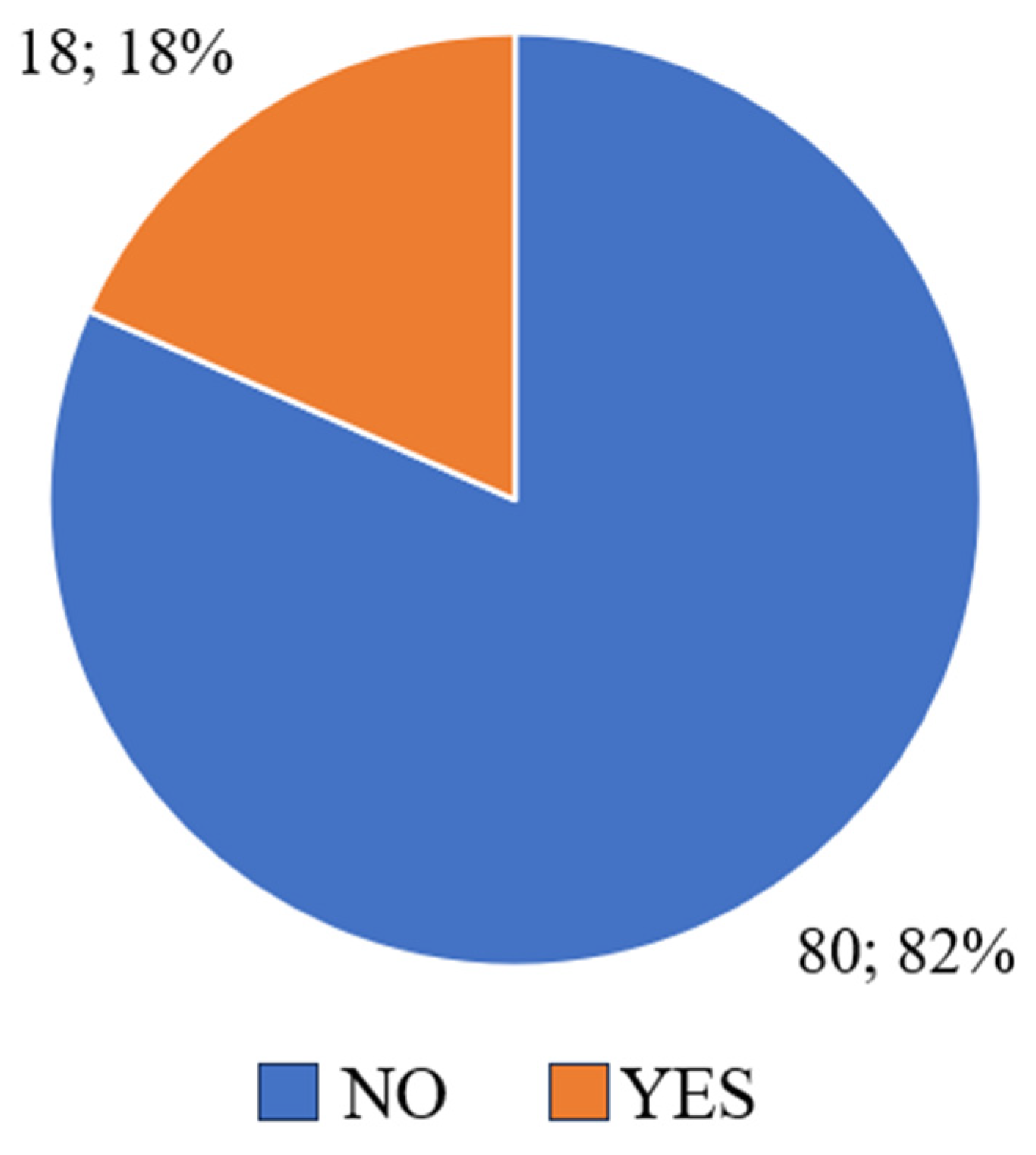

3.2.5. Physical Activity as a Means of Weight Control

3.3. Psychological Variability Depending on BMI

3.3.1. Respondents’ Answers to the Question “Has Your Body Shape Affected the Way You Think About Yourself?” Taking into Account BMI

3.3.2. Answers to the Question “Were You Dissatisfied with Your Body Shape?” Taking into Account BMI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ługowska, K.; Krzęcio-Nieczyporuk, E.; Trafiałek, J.; Kolanowski, W. The Impact of Increased Physical Activity at School on the Nutritional Behavior and BMI of 13-Year-Olds. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel-Berges, M.L.; De Miguel-Etayo, P.; Larruy-García, A.; Jimeno-Martinez, A.; Pellicer, C.; Moreno Aznar, L. Lifestyle Risk Factors for Overweight/Obesity in Spanish Children. Children 2022, 9, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, S.R.; Arnett, D.K.; Eckel, R.H.; Gidding, S.S.; Hayman, L.L.; Kumanyika, S.; Robinson, T.N.; Scott, B.J.; St Jeor, S.; Williams, C.L. Overweight in children and adolescents: Pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation 2005, 111, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Schuler, B.R.; Kobulsky, J.M.; Sarwer, D.B. The association between adverse childhood experiences and childhood obesity: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.A.; Hardy, S.T.; Jones, R.; Ng, C.; Kramer, M.R.; Narayan, K.M.V. Changes in the Incidence of Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2021053708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, A.; Tsur, A.M.; Bardugo, A.; Twig, G. Adolescent and Childhood Obesity and Excess Morbidity and Mortality in Young Adulthood—A Systematic Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2021, 10, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprio, S.; Santoro, N.; Weiss, R. Childhood Obesity and the Associated Rise in Cardiometabolic Complications. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothiraj, P.; Shamal, C.; Krishnan, V. Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life Amongst Indian Obese School Children: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, A.; Sarapis, K.; Moschonis, G. The Effect of Maternal Overweight and Obesity Pre-Pregnancy and During Childhood in the Development of Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, B.; Moorthy, M. Causes of Obesity: A Review. Clin. Med. 2023, 23, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duis, J.; Butler, M.G. Syndromic and Nonsyndromic Obesity: Underlying Genetic Causes in Humans. Adv. Biol. 2022, 6, e2101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makles, P. Kultura zdrowotna w profilaktyce otyłości jako sposób spędzania wolnego czasu przez dzieci w wieku szkolnym w Polsce. (Health Culture in Obesity Prevention as a Way of Spending Free Time by School-Age Children in Poland). Kult. Przemiany Eduk. 2022, 11, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Swinburn, B.A.; Lawrence, M.A. A Systematic Policy Approach to Changing the Food System and Physical Activity Environments to Prevent Obesity. Aust. N. Z. Health Policy 2008, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trost, S.G.; Kerr, L.M.; Ward, D.S.; Pate, R.R. Physical Activity and Determinants of Physical Activity in Obese and Non-Obese Children. Int. J. Obes. 2001, 25, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, I.; Leblanc, A.G. Systematic Review of the Health Benefits of Physical Activity and Fitness in School-Aged Children and Youth. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.B.; Riddoch, C.; Kriemler, S.; Hills, A.P. Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boreham, C.; Riddoch, C. The Physical Activity, Fitness and Health of Children. J. Sports Sci. 2001, 19, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.P.; King, N.A.; Armstrong, T.P. The Contribution of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviours to the Growth and Development of Children and Adolescents: Implications for Overweight and Obesity. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Davis, M.G.; Robinson, T.N.; Stone, E.J.; McKenzie, T.L.; Young, J.C. Promoting Physical Activity in Children and Youth: A Leadership Role for Schools—A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Physical Activity Committee) in Collaboration with the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young and Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation 2006, 114, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropski, J.A.; Keckley, P.H.; Jensen, G.L. School-Based Obesity Prevention Programs: An Evidence-Based Review. Obesity 2008, 16, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gortmaker, S.L.; Peterson, K.; Wiecha, J.; Sobol, A.M.; Dixit, S.; Fox, M.K.; Laird, N. Reducing Obesity via a School-Based Interdisciplinary Intervention among Youth: Planet Health. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999, 153, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, K.K.; Lawson, C.T. Do Attributes in the Physical Environment Influence Children’s Physical Activity? A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrottesley, S.V.; Bosire, E.N.; Mukoma, G.; Motlhatlhedi, M.; Mabena, G.; Barker, M.; Hardy-Johnson, P.; Fall, C.; Norris, S.A. Age and Gender Influence Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Behaviours in South African Adolescents and Their Caregivers: Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition Initiative (TALENT). Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5187–5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A Review of Correlates of Physical Activity of Children and Adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H.W., III; Craig, C.L.; Lambert, E.V.; Inoue, S.; Alkandari, J.R.; Leetongin, G.; Kahlmeier, S.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. The Pandemic of Physical Inactivity: Global Action for Public Health. Lancet 2012, 380, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, W.B.; Malina, R.M.; Blimkie, C.J.; Daniels, S.R.; Dishman, R.K.; Gutin, B.; Hergenroeder, A.C.; Must, A.; Nixon, P.A.; Pivarnik, J.M.; et al. Evidence Based Physical Activity for School-Age Youth. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Zembura, P.; Korcz, A.; Nałęcz, H.; Cieśla, E. Results from Poland’s 2022 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomayko, E.J.; Tovar, A.; Fitzgerald, N.; Howe, C.L.; Hingle, M.D.; Murphy, M.P.; Muzaffar, H.; Going, S.B.; Hubbs-Tait, L. Parent Involvement in Diet or Physical Activity Interventions to Treat or Prevent Childhood Obesity: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Slater, A. NetGirls: The Internet, Facebook, and Body Image Concern in Adolescent Girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, A.E.; Wilfley, D.E.; Eddy, K.T.; Boutelle, K.N.; Zucker, N.; Peterson, C.B.; Le Grange, D.; Celio-Doyle, A.; Goldschmidt, A.B. Secretive Eating among Youth with Overweight or Obesity. Appetite 2017, 114, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Agras, W.S.; Hammer, L.D. Risk Factors for the Emergence of Childhood Eating Disturbances: A Five-Year Prospective Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 25, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.R.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Haines, J.; Gortmaker, S.; Mitchell, K.F.; Gillman, M.W.; Taveras, E.M. Associations of Parental Control of Feeding with Eating in the Absence of Hunger and Food Sneaking, Hiding, and Hoarding. Child. Obes. 2013, 9, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Shafran, R. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Eating Disorders: A “Transdiagnostic” Theory and Treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favieri, F.; Marini, A.; Casagrande, M. Emotional Regulation and Overeating Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braet, C.; Claus, L.; Goossens, L.; Moens, E.; Van Vlierberghe, L.; Soetens, B. Differences in Eating Style between Overweight and Normal-Weight Youngsters. J. Health Psychol. 2008, 13, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Cebolla, A.; Etchemendy, E.; Gutiérrez-Maldonado, J.; Ferrer-García, M.; Botella, C.; Baños, R. Emotional Eating and Food Intake after Sadness and Joy. Appetite 2013, 66, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge Eating as Escape from Self-Awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowska, J.; Hamulka, J.; Wadolowska, L.; Górnicka, M.; Czarniecka-Skubina, E.; Gutkowska, K. Restrained Eating and Disinhibited Eating: Association with Diet Quality and Body Weight Status Among Adolescents. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, G.; Gallè, F.; Dinacci, L.; Liberti, F.; Cunti, A.; Valerio, G. Self-Perception Profile, Body Image Perception and Satisfaction in Relation to Body Mass Index: An Investigation in a Sample of Adolescents from the Campania Region, Italy. Children 2024, 11, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latzer, Y.; Stein, D. A Review of the Psychological and Familial Perspectives of Childhood Obesity. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pont, S.J.; Puhl, R.; Cook, S.R.; Slusser, W.; Section on Obesity; Obesity Society. Stigma Experienced by Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20173034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keeffe, M.; Flint, S.W.; Watts, K.; Rubino, F. Knowledge Gaps and Weight Stigma Shape Attitudes Toward Obesity. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, A.; Araujo Coelho, D.R.; Vieira, W.F.; Moehlecke Iser, B.; Lampert, R.M.F.; Traebert, E.; Silva, B.B.D.; Oliveira, B.H.; Leão, G.M.; Souza, G.; et al. Factors Associated with the Development of Depression and the Influence of Obesity on Depressive Disorders: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Arenas, J.J.; Ruiz Martínez, A.O. Relationship between Self-Esteem and Body Image in Children with Obesity. Rev. Mex. Trastor. Aliment. 2015, 6, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Strong, C.; Tsai, M.C.; Lin, Y.C. The Relationship between Children’s Overweight and Quality of Life: A Comparison of Sizing Me Up, PedsQL and Kid-KINDL. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019, 19, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, S.J.; Robinson, T.N.; Haydel, K.F.; Killen, J.D. Are Overweight Children Unhappy? Body Mass Index, Depressive Symptoms, and Overweight Concerns in Elementary School Children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Q.; Xu, F.; Wang, F.; Luo, S.; An, X.; Chen, J.; Tang, N.; Jiang, X.; Liang, X. Effect of Physical Activity on Anxiety, Depression and Obesity Index in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: A Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Presnell, K. Prevention of Eating Disorders: A Review of Programs and Their Effectiveness. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, M.; Allès, B.; Gisch, U.A.; Shankland, R.; Hercberg, S.; Touvier, M.; Leys, C.; Péneau, S. Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations between Self-Esteem and BMI Depends on Baseline BMI Category in a Population-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, K.; Chard, C.; Castro, E.; Nelson, D. The Influence of a Girls’ Health and Well-Being Program on Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Physical Activity Enjoyment. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardouly, J.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Vartanian, L.R.; Halliwell, E. Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image 2015, 13, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Ventura, A.K. Preventing Childhood Obesity: What Works? Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33 (Suppl. S1), S74–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerbell, C.D.; Waters, E.; Edmunds, L.D.; Kelly, S.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J. Interventions for Preventing Obesity in Children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 3, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, N.; Balding, J.; Gentle, P.; Kirby, B. Patterns of Physical Activity among 11 to 16 Year Old British Children. BMJ 1990, 301, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migueles, J.H.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Lubans, D.R.; Henriksson, P.; Torres-Lopez, L.V.; Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Plaza-Florido, A.; Gil-Cosano, J.J.; Henriksson, H.; Escolano-Margarit, M.V.; et al. Effects of an Exercise Program on Cardiometabolic and Mental Health in Children with Overweight or Obesity: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2324839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, G.J.; Fink, T.; Brady, T.; Young, D.R.; Dickerson, F.B.; Goldsholl, S.; Findling, R.L.; Stepanova, E.A.; Scheimann, A.; Dalcin, A.T.; et al. Physical Activity Levels and Screen Time among Youth with Overweight/Obesity Using Mental Health Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Colman, I.; Goldfield, G.S.; Janssen, I.; Wang, J.; Podinic, I.; Tremblay, M.S.; Saunders, T.J.; Sampson, M.; Chaput, J.P. Combinations of Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Sleep Duration and Their Associations with Depressive Symptoms and Other Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deatrick, J.A.; Klusaritz, H.; Atkins, R.; Bolick, A.; Bowman, C.; Lado, J.; Schroeder, K.; Lipman, T.H. Engaging with the Community to Promote Physical Activity in Urban Neighborhoods. Am. J. Health Promot. 2019, 33, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszyńska, J.; Ring-Dimitriou, S.; Thivel, D.; Weghuber, D.; Hadjipanayis, A.; Grossman, Z.; Ross-Russell, R.; Dereń, K.; Mazur, A. Physical Activity in the Prevention of Childhood Obesity: The Position of the European Childhood Obesity Group and the European Academy of Pediatrics. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 535705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolnicka, K.; Charzewska, J.; Taraszewska, A.; Czarniecka, R.; Jaczewska-Schuetz, J.; Bieńko, N.; Olszewska, E.; Wajszczyk, B.; Jarosz, M. Intervention for Improvement of the Diet and Physical Activity of Children and Adolescents in Poland. Rocz. Państw. Zakł. Hig. 2020, 71, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynynen, S.T.; van Stralen, M.M.; Sniehotta, F.F.; Araújo-Soares, V.; Hardeman, W.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; Vasankari, T.; Hankonen, N. A Systematic Review of School-Based Interventions Targeting Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour among Older Adolescents. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 9, 22–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, L.M.; Mair, J.L.; Kirby, K.; Murtagh, E.; Murphy, M.H. School-Based Interventions to Reduce Sedentary Behaviour in Children: A Systematic Review. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 520–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BMI | Health Resort Hospital | Clinical Hospital | Secondary School | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| starvation | <16.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| emaciation | 16.0–16.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| underweight | 17.0–18.5 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| normal weight | 18.5–24.9 | 7 | 9 | 21 |

| overweight | 25.0–29.9 | 7 | 10 | 4 |

| obesity class I | 30.0–34.9 | 11 | 6 | 0 |

| obesity class II | 35.0–39.9 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| obesity class III | ≥40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Has Your Body Shape Affected the Way You Think About Yourself? | BMI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal Weight | Overweight | Obesity Class I | Obesity Class II | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| never | 1 | 14% | 9 | 20% | 1 | 5% | 2 | 12% |

| almost never | 1 | 14% | 1 | 2% | 1 | 5% | 2 | 12% |

| very rarely | 1 | 14% | 9 | 20% | 1 | 5% | 2 | 12% |

| rarely | 1 | 14% | 5 | 11% | 4 | 19% | 2 | 12% |

| often | 3 | 43% | 7 | 16% | 4 | 19% | 3 | 18% |

| very often | 0 | 0% | 7 | 16% | 8 | 38% | 3 | 18% |

| all the time | 0 | 0% | 6 | 14% | 2 | 10% | 3 | 18% |

| Chi-square | χ2 = 17.648 | df = 18 | p = 0.0479 | |||||

| Have You Been Unhappy with Your Body Shape? | BMI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal Weight | Overweight | Obesity Class I | Obesity Class II | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| never | 3 | 43% | 9 | 20% | 1 | 5% | 1 | 6% |

| almost never | 0 | 0% | 8 | 18% | 1 | 5% | 1 | 6% |

| very rarely | 2 | 29% | 3 | 7% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 18% |

| rarely | 0 | 0% | 5 | 11% | 2 | 10% | 3 | 18% |

| often | 1 | 14% | 8 | 18% | 6 | 29% | 2 | 12% |

| very often | 1 | 14% | 5 | 11% | 8 | 38% | 3 | 18% |

| all the time | 0 | 0% | 6 | 14% | 3 | 14% | 4 | 24% |

| Chi-square | χ2 = 27.43 | df = 18 | p = 0.0287 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wąsacz, M.; Sarzyńska, I.; Ochojska, D.; Błajda, J.; Bartkowska, O.; Brydak, K.; Stańczyk, S.; Bator, M.; Kopańska, M. Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101690

Wąsacz M, Sarzyńska I, Ochojska D, Błajda J, Bartkowska O, Brydak K, Stańczyk S, Bator M, Kopańska M. Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(10):1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101690

Chicago/Turabian StyleWąsacz, Małgorzata, Izabela Sarzyńska, Danuta Ochojska, Joanna Błajda, Oliwia Bartkowska, Karolina Brydak, Szymon Stańczyk, Martyna Bator, and Marta Kopańska. 2025. "Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study" Nutrients 17, no. 10: 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101690

APA StyleWąsacz, M., Sarzyńska, I., Ochojska, D., Błajda, J., Bartkowska, O., Brydak, K., Stańczyk, S., Bator, M., & Kopańska, M. (2025). Psychosocial Consequences of Excess Weight and the Importance of Physical Activity in Combating Obesity in Children and Adolescents: A Pilot Study. Nutrients, 17(10), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101690