Do Italian ObGyn Residents Have Enough Knowledge to Counsel Women About Nutritional Facts? Results of an On-Line Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Survey Questionnaire

- (1)

- Participants’ characteristics: age, gender, region of practice, year of residency, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, supplementation use, and having children.

- (2)

- Personal perceptions about the importance of the current topic: how much do they feel confident about women’s nutrition, and if they think this topic deserves more time and space in the Specialty Program.

- (3)

- Residents’ knowledge: participants were asked to answer 9 simple questions about:

- -

- recommended percentage of macronutrients (proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates) intake during a balanced meal [24];

- -

- recommended portions of fruit and vegetables per day [24];

- -

- recommended portions of fish per week [24];

- -

- types of food rich in Vitamin D [17];

- -

- recommended sugar intake per day [24];

- -

- role of dried fruit in pregnancy [25];

- -

- Vitamin D recommended intake in menopause [26];

- -

- nutritional advice in premenstrual syndrome [27];

- -

- nutritional advice for obese pregnant women [8].

- (4)

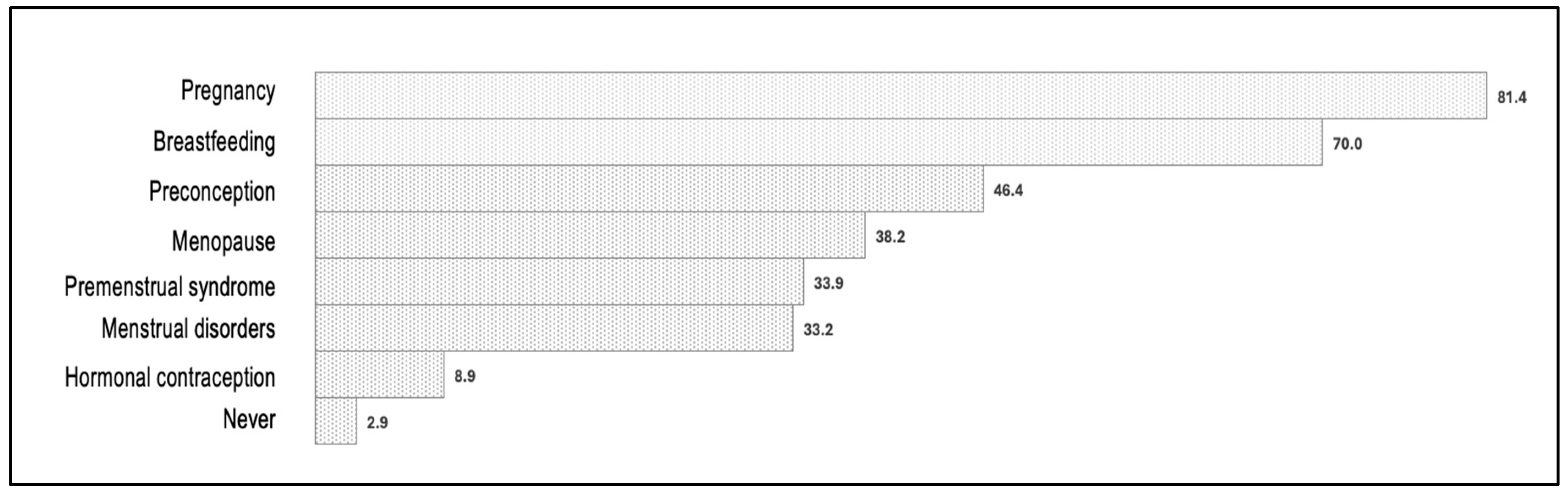

- Prescription of Supplements by Italian residents in Obstetrics and Gynecology: questions regarding when and which type of supplements they generally recommend.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant’s Characteristics

3.2. Personal Perceptions About the Importance of the Current Topic

3.3. Residents’ Knowledge

3.4. Prescription of Supplements by Italian Residents in Obstetrics and Gynecology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ObGyns | Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| AGUI | Associazione Ginecologi Universitari Italiani |

| ObGyn | Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

References

- Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Georgieff, M.K. Advocacy for Improving Nutrition in the First 1000 Days to Support Childhood Development and Adult Health. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20173716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayi, T.; Ozgoren, M. Effects of the Mediterranean Diet on the Components of Metabolic Syndrome. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Dastmalchi, L.N.; Gulati, M.; Michos, E.D. A Heart-Healthy Diet for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: Where Are We Now? Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2023, 19, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolinoy, D.C.; Weidman, J.R.; Jirtle, R.L. Epigenetic Gene Regulation: Linking Early Developmental Environment to Adult Disease. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 23, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junien, C. Impact of Diets and Nutrients/Drugs on Early Epigenetic Programming. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006, 29, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, H.; Fernald, L. The Nexus Between Nutrition and Early Childhood Development. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017, 37, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirawan, F.; Yudhantari, D.G.A.; Gayatri, A. Pre-Pregnancy Diet to Maternal and Child Health Outcome: A Scoping Review of Current Evidence. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2023, 56, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutrizione in Gravidanza e Durante L’allattamento. Raccomandazioni della Fondazione Confalonieri Ragonese, AGUI, SIGO, AGOI. 4 June 2018. Available online: https://www.sigo.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/LG_NutrizioneinGravidanza.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-Mcgregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and Child Undernutrition and Overweight in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, I.; Kasapidou, E.; Dagklis, T.; Leonida, I.; Leonida, C.; Bakaloudi, D.R.; Chourdakis, M. Nutrition in Pregnancy: A Comparative Review of Major Guidelines. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2020, 75, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beta, J.; Khan, N.; Khalil, A.; Fiolna, M.; Ramadan, G.; Akolekar, R. Maternal and Neonatal Complications of Fetal Macrosomia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catov, J.M.; Margerison-Zilko, C. Pregnancy as a Window to Future Health: Short-Term Costs and Consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 406–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, A.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Borge, T.C.; M Hård af Segerstad, E.; Imberg, H.; Mårild, K.; Størdal, K. Maternal Diet in Pregnancy and the Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the Offspring: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 121, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavatta, A.; Parisi, F.; Mandò, C.; Scaccabarozzi, C.; Savasi, V.M.; Cetin, I. Role of Inflammaging on the Reproductive Function and Pregnancy. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 64, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correction to: 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2020, 141, E774, Erratum in Circulation 2019, 140, e596–e646. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutrition During Pregnancy|ACOG. Available online: https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/nutrition-during-pregnancy (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- LARN—V Revisione. Available online: https://www.biomediashop.net/index.php?id_product=64&controller=product&id_lang=2 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Harak, S.S.; Shelke, S.P.; Mali, D.R.; Thakkar, A.A. Navigating Nutrition through the Decades: Tailoring Dietary Strategies to Women’s Life Stages. Nutrition 2025, 135, 112736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.L.; Cuthbert, A.; Weeks, J.; Venkatramanan, S.; Larvie, D.Y.; De-Regil, L.M.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Daily Oral Iron Supplementation during Pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 8, CD004736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNulty, H.; Rollins, M.; Cassidy, T.; Caffrey, A.; Marshall, B.; Dornan, J.; McLaughlin, M.; McNulty, B.A.; Ward, M.; Strain, J.J.; et al. Effect of Continued Folic Acid Supplementation beyond the First Trimester of Pregnancy on Cognitive Performance in the Child: A Follow-up Study from a Randomized Controlled Trial (FASSTT Offspring Trial). BMC Med. 2019, 17, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminiuc, R.; Ţurcanu, D. Impact of Nutritional Diet Therapy on Premenstrual Syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1079417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Martin, D.; Waldron, M.; Bruinvels, G.; Farrant, L.; Fairchild, R. Nutritional Practices to Manage Menstrual Cycle Related Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2024, 37, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, S.; Steenson, S.; Creedon, A.; Stanner, S. The Role of Diet in Managing Menopausal Symptoms: A Narrative Review. Nutr. Bull. 2023, 48, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Berni Canani, S.; Censi, L.; Gennaro, L.; Leclercq, C.; Scognamiglio, U.; Sette, S.; Ghiselli, A. The 2018 Revision of Italian Dietary Guidelines: Development Process, Novelties, Main Recommendations, and Policy Implications. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 861526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melero, V.; Assaf-Balut, C.; de la Torre, N.G.; Jiménez, I.; Bordiú, E.; Del Valle, L.; Valerio, J.; Familiar, C.; Durán, A.; Runkle, I.; et al. Benefits of Adhering to a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Pistachios in Pregnancy on the Health of Offspring at 2 Years of Age. Results of the San Carlos Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevention Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccomandazioni Mediche per La Donna in Menopausa—SIGO. Available online: https://www.sigo.it/raccomandazioni-mediche-per-la-donna-in-menopausa/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Oboza, P.; Ogarek, N.; Wójtowicz, M.; Rhaiem, T.B.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M.; Kocełak, P. Relationships between Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Diet Composition, Dietary Patterns and Eating Behaviors. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, M.; Sarno, L. Alimentazione e Donna: La Nutrizione nelle Varie Fasi della Vita Femminile; Eli. Medica: Gevgelija, Macedonia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior. 25 November 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/336656/9789240015128-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Piccoli, G.B.; Cupisti, A. “Let Food Be Thy Medicine…”: Lessons from Low-Protein Diets from around the World. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Alashqar, A.; El Sabeh, M.; Miyashita-Ishiwata, M.; Reschke, L.; Brennan, J.T.; Fader, A.; Borahay, M.A. Diet and Nutrition in Gynecological Disorders: A Focus on Clinical Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachey, S.M.; Hamilton, C.; Goins, B.; Underwood, P.; Chao, A.M.; Dolin, C.D. Nutrition Education and Nutrition Knowledge Among Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents. J. Women’s Health 2024, 33, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anelli, G.M.; Parisi, F.; Sarno, L.; Fornaciari, O.; Carlea, A.; Coco, C.; Porta, M.D.; Mollo, N.; Villa, P.M.; Guida, M.; et al. Associations between Maternal Dietary Patterns, Biomarkers and Delivery Outcomes in Healthy Singleton Pregnancies: Multicenter Italian GIFt Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branum, A.M.; Bailey, R.; Singer, B.J. Dietary Supplement Use and Folate Status during Pregnancy in the United States. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.M.; Arthurs, A.L.; Smith, M.D.; Roberts, C.T.; Jankovic-Karasoulos, T. High Folate, Perturbed One-Carbon Metabolism and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.W.; Ayling, J.E. The Extremely Slow and Variable Activity of Dihydrofolate Reductase in Human Liver and Its Implications for High Folic Acid Intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 15424–15429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.W.; Norwitz, S.G.; Norwitz, E.R. The Impact of Iron Overload and Ferroptosis on Reproductive Disorders in Humans: Implications for Preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.; Black, R.E.; Smith, E.; Shankar, A.H.; Christian, P. Micronutrient Supplements in Pregnancy: An Urgent Priority. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decreto Interministeriale Recante Gli Standard, i Requisiti e Gli Indicatori di Attività Formativa e Assistenziale delle Scuole di Specializzazione di Area Sanitaria—MIM. Available online: https://www.mim.gov.it/web/guest/-/decreto-interministeriale-recante-gli-standard-i-requisiti-e-gli-indicatori-di-attivita-formativa-e-assistenziale-delle-scuole-di-specializzazione-di- (accessed on 2 May 2025).

| Characteristics | n = 258 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 59 (22.9) |

| Female | 198 (76.7) |

| Not declared | 1 (0.4) |

| Age | 29.4 (2.6) |

| Region of practice | |

| Northern Italy | 78 (30.2) |

| Central Italy | 53 (20.5) |

| Southern and Islands Italy | 137 (49.2) |

| Year of Residency | |

| 1st | 60 (23.3) |

| 2nd | 34 (13.2) |

| 3rd | 66 (25.6) |

| 4th | 71 (27.5) |

| 5th | 25 (9.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.8) |

| Smoking | |

| Yes | 59 (22.9) |

| No | 179 (69.4) |

| Ex smoker | 16 (6.2) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.6) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| >3 times/week | 3 (1.2) |

| 2–3 times a week | 26 (10.1) |

| Once a week or less | 172 (66.7) |

| No | 53 (20.5) |

| unknown | 4 (1.6) |

| Physical activity | |

| <150 min/week | 191 (74.0) |

| ≥150 min/week | 67 (26.0) |

| Use of supplements | |

| yes | 99 (38.4) |

| Having children | |

| yes | 13 (5.0) |

| Topics | Correct Answers n (%) |

|---|---|

| Macronutrient distribution | 40 (15.5) |

| Portions of fruit and vegetables per day | 106 (41.1) |

| Portions of fish per week | 227 (88.0) |

| Food rich in vitamin D | 129 (50) |

| Sugar intake | 173 (67.1) |

| Dried fruit in pregnancy | 200 (77.5) |

| Nutrition and menopause | 210 (81.4) |

| Nutrition and premenstrual syndrome | 155 (60.1) |

| Nutrition in obese pregnant women | 178 (69) |

| Folate Supplementation | N (%) |

| 5-Methyl-tetrahydrofolate | 77 (29.8) |

| Folic Acid | 130 (50.4) |

| It’s the same | 7 (2.7) |

| I don’t know the difference | 44 (17.1) |

| Iron Supplementation | N (%) |

| Ferrous sulphate | 180 (7.0) |

| Liposomal or sucrosomial iron | 83 (32.2) |

| Iron bysglicinate | 5 (1.9) |

| Ferrous sulphate as first line and other types as second line | 97 (37.6) |

| It’s the same | 16 (6.2) |

| I don’t know the difference | 39 (15.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarno, L.; Colacurci, D.; Ranieri, E.; Nappi, R.E.; Guida, M., on behalf of A.G.U.I. (Associazione Ginecologi Universitari Italiani). Do Italian ObGyn Residents Have Enough Knowledge to Counsel Women About Nutritional Facts? Results of an On-Line Survey. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1654. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101654

Sarno L, Colacurci D, Ranieri E, Nappi RE, Guida M on behalf of A.G.U.I. (Associazione Ginecologi Universitari Italiani). Do Italian ObGyn Residents Have Enough Knowledge to Counsel Women About Nutritional Facts? Results of an On-Line Survey. Nutrients. 2025; 17(10):1654. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101654

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarno, Laura, Dario Colacurci, Eleonora Ranieri, Rossella E. Nappi, and Maurizio Guida on behalf of A.G.U.I. (Associazione Ginecologi Universitari Italiani). 2025. "Do Italian ObGyn Residents Have Enough Knowledge to Counsel Women About Nutritional Facts? Results of an On-Line Survey" Nutrients 17, no. 10: 1654. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101654

APA StyleSarno, L., Colacurci, D., Ranieri, E., Nappi, R. E., & Guida, M., on behalf of A.G.U.I. (Associazione Ginecologi Universitari Italiani). (2025). Do Italian ObGyn Residents Have Enough Knowledge to Counsel Women About Nutritional Facts? Results of an On-Line Survey. Nutrients, 17(10), 1654. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101654