Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Herb | Author/ Year | Country | Baseline Disease Activity | Number of Patients Randomized | Control | Intervention | Use of Concomitant UC Medications | Treatment Duration | Select Results at End of Study (Intervention vs. Control) | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcuma longa | Banerjee et al., 2021 [20] | India | Mild–moderate UC | 69 | Placebo with oral and rectal mesalamine | 50 mg bioenhanced curcumin PO BID with oral and rectal mesalamine | Patients were biologic and immunomodulator naive | 6 weeks, 3 months | (1) Clinical response: 52.9% vs. 14.3% (p = 0.001) at 6 weeks; 58.8% vs. 28.6% at 3 months (p = 0.013) (2) Clinical remission): 44.1% vs. 0% (p < 0.01) at 6 weeks; 55.9% vs. 5.7% at 3 months (p < 0.01) (3) Endoscopic remission: 35.3% vs. 0% (p < 0.001) at 6 weeks; 44% vs. 5.7% at 3 months (p < 0.001) | No difference in mild (i.e., abdominal bloating) or severe AEs |

| Kedia et al., 2017 [21] | India | Mild–moderate UC | 62 | Placebo with oral mesalamine | 150 mg purified curcumin capsules PO TID with oral mesalamine | 6.5% used AZA | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 20.7% vs. 36.4% (p = 0.18) (2) Clinical remission: 31.3% vs. 27.3% (p = 0.75) (3) Mucosal healing: 34.5% vs. 30.3% (p = 0.72) | No difference in mild (i.e., self-limited arthralgias) AEs | |

| Kumar et al., 2018 [22] | India | Mild–severe UC | 53 | Placebo powder QD with oral mesalamine | 10 g/d PO C. longa powder QD with 2.4 g/d PO mesalamine | Not disclosed | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 60.7% vs. 52% (p = 0.412) (2) Reduction in fecal calprotectin by ≥25 units: 83.3% vs. 50% (p = 0.034) | No difference between groups | |

| Lang et al., 2015 [23] | Israel | Mild–moderate UC | 50 | Placebo with oral and enema/suppository mesalamine | 1.5 g curcumin capsules PO BID with oral and enema/suppository mesalamine | Immunomodulators (AZA, 6-MP) allowed if stable dose. No recent use of steroids, cyclosporine, or anti-TNFα agents permitted. | 4 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 65.3% vs. 12.5% (p < 0.001) (2) Clinical remission: 53.8% vs. 0% (p = 0.01) (3) Endoscopic response: 45.4% vs. 0% (p < 0.043) (4) Endoscopic remission: 38% vs. 0% (p = 0.04) | No difference between groups in mild (nausea, increased stool frequency, bloating) or severe (UC flair, peptic ulcer) AEs | |

| Masoodi et al., 2018 [24] | Iran | Mild–moderate UC | 56 | Placebo with oral mesalamine | 80 mg curcuminoids nanomicelles PO TID with oral mesalamine | Topical mesalamine, prednisolone, azathioprine, or TNFα-inhibitors allowed. | 4 weeks | (1) Clinical symptoms: Difference between groups in urgency of defecation score (p = 0.041), but not in number of daily bowel movements (p = 0.13), blood in stool (p = 0.781), or nocturnal bowel movements (p = 0.131) (2) Mean SCCAI: 1.71 ± 1.84 vs. 2.68 ± 2.09 (p = 0.050) | No significant difference between mild (flatulence, dyspepsia, headache, increased headache, nausea, yellow stool) AEs | |

| Sadeghi et al., 2020 [25] | Iran | Mild–moderate UC | 70 | Placebo capsules | 500 mg curcumin capsules PO TID with meals | Concomitant salicylates, immunomodulators, or steroids allowed; cannot be on TNFα inhibitors | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 93.5% vs. 59.4% (p < 0.001) (2) Clinical remission: 83.9% vs. 43.8% (p = 0.001) (3) Change in IBDQ-9: 9.5 ± 8.4 (p = 0.001) vs. 4.09 ± 7.7 (p = 0.004) | Mild AEs reported (skin allergy, dyspepsia, heartburn) | |

| Shivakumar et al., 2011 [26] | India | Active UC | 53 | Placebo powder PO QD + mesalamine/steroids | 10 g curcumin powder QD + mesalamine/steroids | Not disclosed | 8 weeks | (1) Reduction in Mayo score: 0.56 ± 0.71 vs. 0.43 ± 0.78 (p = 0.56) (2) Decrease of 1 point in histological activity score: 62.5% vs. 43.47% (p = 0.19) (3) Fecal calprotectin levels: 175.22 ± 179.56 vs. 65.19 ± 240.57 μg/g (p = 0.001) | Not reported | |

| Singla, 2014 [27] | India | Mild to moderate distal UC | 45 | Placebo enema with oral mesalamine | 140 mg NCB-02 enema QHS with oral mesalamine | Steroids, 5-ASA, AZA | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 56.5% vs. 36.4% (p = 0.175) (2) Clinical remission: 43.4% vs. 22.7% (p = 0.14) (3) Endoscopic response: 52.2% vs. 36.4% (p = 0.29) | No difference in severe AEs (UC flare) | |

| Indigo naturalis | Naganuma et al., 2018 [28] | Japan | Moderate UC | 86 | Placebo capsules | 4250 mg, 125 mg, or 62.5 mg in each capsule IN powder capsules PO BID (total 0.5, 1, or 2 g/d) | Steroids, thiopurines, TNFα inhibitors | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 0.5 g IN 69.6% (p = 0.002); 1 g 75% (p = 0.0001); 2 g IN 81% (p < 0.0001) vs. 13.6% (2) Clinical remission: 0.5 g IN 26.1% (p = 0.0959); 1 g IN 55% (p = 0.0004); 2 g IN 38.1% (p = 0.0093) vs. 4.5% (3) Endoscopic response: 0.5 g IN 56.5% (p < 0.0045); 1 g IN 60% (p < 0.0032); 2 g IN 47.6% (p < 0.0217) vs. 13.6% | Mild AEs included liver dysfunction, headache, epigastric/abdominal pain, nausea |

| Uchiyama et al., 2020 [29] | Japan | Mild–moderate UC | 46 | 500 mg rice starch capsule PO BID | 500 mg IN powder capsules PO BID | 5-ASA, prednisolone, AZA, biologics | 2 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 82.6% vs. 26.3% (p = 0.0003) (2) Marked clinical response: 60.9% vs. 5.3% (p = 0.0002) | Mild AEs included headache, constipation, palpitations | |

| Andrographis paniculata | Sandborn et al., 2013 [30] | USA Canada Germany Romania Ukraine | Mild to moderate UC | 223 | Placebo capsules | 400 mg or 600 mg capsules containing A. paniculata ethanol extract (HMPL-004) PO TID (total 1.2 g or 1.8 g/d) | Concomitant mesalamine, sulfasalazine, balsalazide, or olsalazine. Subjects with use of other UC meds within 6 weeks were excluded. | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 1200 mg 44.6%, (p = 0.5924) 1800 mg 59.5% (p = 0.0183), combined 1200 mg + 1800 mg 52% (p = 0.0465) vs. 40% (2) Clinical remission: 1200 mg 33.8% (p = 0.2718), 1800 mg 37.8% (p = 0.1011), 1200 mg + 1800 mg 35.8% (p = 0.2516) vs. 25.3% (3) Endoscopic response: 1200 mg 37.8% (p = 0.5281), 1800 mg 50% (p = 0.0404), 1200 mg + 1800 mg 43.95% (p = 0.1025) vs. 33.3% | No significant difference in mild to moderate (rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspepsia, AST/Alk Phos, GGT elevation) or severe AEs |

| Tang et al., 2013 [31] | China | Mild to moderate UC | 125 | Oral mesalazine | 400 mg capsules containing A. paniculata ethanol extract (HMPL-004) PO TID (total 1.2 g/d) | No other concomitant UC medications permitted, but previous treatment with 5-ASA and/or steroids permitted | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical remission: 21% vs. 16% (2) Partial clinical remission: 36% vs. 36% (3) Clinical improvement: 19% vs. 29% (4) Endoscopic response: 26% vs. 29% (4) Endoscopic remission: 28% vs. 24% (5) Histologic improvement: 53% vs. 40% (p < 0.001) | 13% int. vs. 27% cont. had ≥1 AE. Mild to moderate AEs included aphthous ulcer, abdominal pain, bloody stools, rash, hematuria, fevers, WBC decrease, and diarrhea among others. 4% int. vs. 0% cont. had severe AEs | |

| Aloe vera | Langmead et al., 2004 [32] | England | Mild to moderate UC | 44 | Placebo liquid | 100 mL Aloe vera gel PO BID | Concomitant 5-ASA, AZA, topical steroids, or none | 4 weeks | (1) Clinical remission: 30% vs. 7% (p = 0.09) (2) Clinical response: 47% vs. 14% (p = 0.048) (3) Sigmoidoscopic remission: 27% vs. 18% (p = 0.69) (4) Histological remission: 29% vs. 44% (p = 0.43) | No difference between groups in mild AEs (abdominal bloating, foot pain, sore throat, ankle swelling, acne, eczema) |

| Pica et al., 2021 [33] | Italy | Mild to moderate active ulcerative proctosigmoiditis | 44 | Placebo enema with oral mesalazine | 60 mL Aloe vera gel enema QD | Not reported | 4 weeks | (1) Change in average DAI: 6.66 ± 1.75 to 3.27 ± 2.07 (p = 0.002) vs. 6.19 ± 1.63 to 5.90 ± 2.16 (p = 0.780) | Not reported | |

| Arthrospira platensis | Moradi et al., 2021 [34] | Iran, UK | Mild to moderate UC | 80 | Placebo capsules | 500 mg Spirulina capsule PO BID before lunch and dinner (total 1 g/d) | Oral or rectal mesalazine, sulfasalazine, prednisolone, AZA | 8 weeks | (1) Anthropometric parameters: No significant difference in body weight, neck circumference (NC), hip circumference (HC), waist circumference (WC), waist to hip ratio (WHR), body mass index (BMI), or blood pressure within each group. (2) Sleep quality: Significant decrease in sleep disturbances (p = 0.004) and sleep quality (p = 0.01) in each group per PSQI over study period. (3) Mood, stress, quality of Life: Significant decrease in stress (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.04) and depression (p = 0.01 vs. p = 0.02) within each group over study period. Increase in SIBDQ (p < 0.001 vs. p = 0.01) within each group. Significant difference in stress score (p = 0.04) and quality of life (p = 0.03) between groups. | Mild bloating |

| Boswellia serrata | Gupta et al., 1997 [35] | India | Mild to moderate active UC | 30 | Oral sulfasalazine | 300 mg encapsulated powdered gum resin of B. serrata PO TID | Not permitted to take other drugs | 6 weeks | (1) Clinical remission: 82.4% vs. 75% (OR 0.673, p = 1) (2) Sigmoidoscopic improvement from grade III to grade 0-I: 75% vs. 75% (OR 0.740, p = 1) | Mild AEs including retrosternal burning, nausea, fullness of abdomen, epigastric pain, anorexia in treatment group |

| Green tea | Dryden et al., 2013 [36] | USA | Mild to moderate UC | 20 | Placebo capsules | Cohort 1: 200 mg Polyphenon E capsule + 1 placebo capsule PO BID Cohort 2: Two 200 mg Polyphenon E capsules PO BID (total 400 mg/d) | Concomitant 5-ASA, AZA, 6-MP allowed; steroids and other immunosuppressants not permitted | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 66.7% vs. 0% (p = 0.03) (2) Clinical remission: 53.3% vs. 0% (p = 0.10) | No significant difference in mild to moderate AEs (heartburn, bloating, flatulence, headache, diarrhea, increased thirst) One patient in the treatment group required hospitalization for C. difficile infection |

| Flaxseed | Morshedzadeh et al., 2019 [37] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 90 | Medical advice and routine medications | 15 g ground flaxseed (GF) mixed in cold water BID or 10 g flaxseed oil (FO) QD | Not permitted to be taking concomitant steroids, AZA, 6-MP, methotrexate, cyclosporine, TNFα inhibitors | 12 weeks | (1) Mayo score: 3.66 (GF) and 3.78 (FO) vs. 4.90 (p = 0.006) (2) IBDQ score: 48.96 (GF) and 48.08 (FO) vs. 42.08 (p < 0.001) (3) Fecal calprotectin (µg/mg): 424.20 (GF) and 484.20 (FO) vs. 602.32 (p = 0.008) | None reported |

| Morshedzadeh et al., 2021 [38] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 90 | Routine treatment protocol | 15 g ground flaxseed (GF) mixed in cold water BID or 10 g flaxseed oil (FO) QD | Not permitted to be taking concomitant steroids, AZA, 6-MP, methotrexate, cyclosporine, TNFα inhibitors | 12 weeks | (1) IL-10 serum levels (pg/dL): 51.29 (GF) and 47.47 (FO) vs. 40.49 (p = 0.002) (2) hs-CRP (mg/L): 4.06 (GF) and 4.00 (FO) vs. 3.8 (p < 0.001) | None reported | |

| Licorice | Sun et al., 2018 [39] | China | Active UC | 94 | Mesalazine enteric-coated tablets | Licorice decoction combined with mesalazine | Mesalazine | 6 weeks | (1) Clinical total effective rate: significantly higher in int. vs. cont. (p < 0.05) (2) Levels of serum IL-6, IL-17, and TNFα: significantly lower in int. vs. cont. (p < 0.05) (3) IBDQ scores: significantly higher in int. vs. cont. (p < 0.05) | None reported |

| Olive oil | Morivaridi et al., 2020 [40] | Iran | Mild to severe UC and remission | 40 | 50 mL canola oil (CO) PO QD | 50 mL extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) PO QD | Mesalazine, prednisolone, azathioprine, others | 20 days of EVOO or CO + 14 days of washout + 20 days of EVOO or CO | (1) Inflammatory markers: Change in mean ESR (−1.18 ± 7.00 vs. 1.87 ± 8.10; p = 0.03); change in mean hs-CRP (−1.31 ± 1.74 vs. 0.36 ± 1.15; p < 0.001); change in TNFα (−3.92 ± 19.33 vs. 8.16 ± 84.13; p = 0.37) (2) Clinical symptoms: GSRS score decreased significantly in EVOO group (p < 0.05); bloating (p = 0.04), constipation (p < 0.001), fecal urgency (p < 0.001), incomplete defecation (p = 0.04) decreased significantly with EVOO. Change in Mayo score not significant. | None reported |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Papada et al., 2018 [41] | Greece, UK, Serbia | Mild to moderate UC | 20 | Placebo tablets | Four 700 mg tablets containing 70% Pistacia lentiscus (PL) PO QD (total 2.8 g/d) | Mesalazine, AZA, steroids | 3 months | (1) Change in oxidative stress markers: No significant differences between groups. OxLDL: −18.4 ± 46 vs. −10.7 ± 58.8; OxLDL/HDL: −1.03 ± 1.96 vs. 0.43 ± 1.83; OxLDL/LDL: −0.39 ± 0.76 vs. −0.27 ± 0.92 (2) Change in amino acids levels: Significant differences between groups in leucine −23.8 nmoL/mL vs. 16.1 nmoL/mL (p = 0.043), serine 13.5 nmoL/mL vs. −16.3 nmoL/mL (p = 0.028), and glutamine 50.3 nmoL/mL vs. −37.5 nmoL/mL (p = 0.038) | None reported |

| Plantago major | Baghizadeh et al., 2021 [42] | Iran | Mild–severe UC and remission | 61 | Two roasted wheat flour capsules PO TID before meals | Two 600 mg p. major seed capsules PO TID before meals (total of 3600 mg/day) | Continuation of routine drugs | 8 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 5.21 ± 3.91 to 2.43 ± 2.71 vs. 4.00 ± 3.81 to 2.09 ± 3.01 (p = 0.282) (2) % subjects with gastrointestinal symptoms: gastroesophageal reflux 32% to 11% vs. 26% to 22% (p = 0.049); gastric pain 29% to 7% vs. 26% to 17% (p = 0.049); distention 79% to 43% vs. 61% to 31% (p = 0.283); constipation 21% to 11% vs. 13% to 4% (p = 0.66); anal pain 25% to 7% vs. 17% to 9% (p = 0.455) | None reported |

| Punica granatum | Kamali et al., 2015 [43] | Iran | Moderate UC | 78 | Placebo syrup | 4 mL syrup containing 6 g dry pomegranate peel PO BID | Concomitant 5-ASA, immunosuppressive and steroids. Prednisolone > 15 mg/day, anti-TNFα agents, cyclosporine excluded. | 10 weeks | (1) Clinical response: 48.3% vs. 36.4% (p = 0.441) (2) Change in symptoms from baseline: Improvement in fecal incontinence (p = 0.031) and general well-being (p = 0.013) in int. group; improvement in general well-being (p = 0.004) in cont. group. | No difference in mild AEs (urticaria, nausea, increased appetite). No serious AEs reported, but 2 int. and 1 cont. discontinued for UC flare. |

| Rose oil | Tavakoli et al., 2019 [44] | Iran | Moderate to severe UC | 40 | 1000 mg liquid paraffin capsules PO TID before meals | 1000 mg rose oil capsules PO TID before meals | Allowed to take concomitant medications | 2 months | (1) Change in partial Mayo score: 3.93 ± 2.24 to 2.14 ± 1.61 (p = 0.022) vs. 3.86 ± 1.46 to 2.14 ± 1.46 (p = 0.014); p = 1 between groups (2) Change in IBDQ-9 scores: 41.6 ± 9.5 to 47.5 ± 8.3 (p = 0.03) vs. 44.6 ± 9.4 to 48.9 ± 6.5 (p = 0.012); p = 0.617 between groups (3) Change in fecal calprotectin: 64.21 ± 93.47 to 34.75 ± 89.45 (p = 0.229) vs. 67.56 ± 138.19 to 33.45 ± 2.72 (p = 0.122) | No difference in mild AEs (gastrointestinal side effects) |

| Saffron | Heydarian et al., 2022 [45] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 80 | Placebo tablets | 100 mg saffron tablet PO QD | 5-ASA, mesalamine, or azathioprine | 8 weeks | (1) Change in mean ESR (mm/h): 15.40 ± 15.07 to 13.60 ± 14.32 (p = 0.002) vs. 13.91 ± 14.86 to 13.11 ± 11.23 (p = 0.622); p = 0.097 for difference in change between groups (2) Change in mean hs-CRP (µg/mL): 4.95 ± 2.03 to 3.76 ± 1.93 (p < 0.001) vs. 4.48 ± 1.95 to 4.56 ± 1.90 (p = 0.613); p = 0.001 for difference in change between groups (3) Change in mean TNFα (pg/mL): 30.51 ± 8.54 to 26.82. ± 7.50 (p < 0.001) vs. 31.80 ± 8.92 to 30.73 ± 8.17 (p = 0.187); p = 0.012 for difference in change between groups (4) Change in mean IBDQ9 score: 43.98 ± 7.39 to 45.33 ± 7.54 (p = 0.013) vs. 40.77 ± 10.53 to 40.69 ± 9.61 (p = 0.973); p = 0.068 for difference in change between groups | None reported |

| Tahvilian et al., 2021 [46] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 80 | Placebo tablets | 100 mg saffron tablet PO QD | 5-ASA, mesalamine, or azathioprine | 8 weeks | (1) Change from baseline SCCAI: −0.82 ± 1.05 vs. −0.02 ± 1.31 (p = 0.004) (2) Change in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (nmol/mL): 0.11 ± 0.69 vs. −0.09 ± 0.39 (p = 0.016) | None reported | |

| Thymus kotschyanus | Vazirian et al., 2022 [47] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 50 | Placebo capsules | 500 mg T. kotschyanus PO in three divided doses daily | Concomitant mesalazine; all other concomitant medications were excluded | 3 months | (1) Fecal calprotectin: 65.66 mg/kg + 37.42 vs. 145.06 mg/kg + 119.87 (p = 0.02) (2) SCCAIQ: median 6 vs. 7 (p = 0.015) (3) SIBDQ: median 43 vs. 39 (p = 0.329) (4) Seo Index: 109.77 + 21.32 vs. 109.94 + 17.94 (p = 0.981) | No difference in mild AEs (mouth ulcers, bloating) |

| Wheat grass | Ben-Arye et al., 2002 [48] | Israel | Colonoscopy with findings of active UC involving the left colon | 24 | 100 mL placebo juice PO QD | 100 mL wheat grass juice PO QD | 5-aminosalicylic acid, prednisone | 1 month | (1) Rectal bleeding (p = 0.025), abdominal pain (p = 0.019), DAI (p = 0.031), and PGA (p = 0.031) were significantly improved in int. vs. cont. (2) Sigmoidoscopic improvement: 78% vs. 30% (p = 0.13) | Mild AEs included nausea, decreased appetite, constipation |

| Zingiber officinale | Nikkhah-Bodaghi et al., 2019 [49] | Iran | Mild to moderate UC | 64 | Placebo capsules | Two 500 mg dried ginger powder capsules PO BID with meals (2000 mg total) | Not reported | 12 weeks | (1) SCCAIQ: 7.6 ± 4.03 to 4.05 ± 1.23 (p = 0.438) vs. 6.2 ± 3.22 to 5.55 ± 2.39 (p = 0.194); p = 0.017 in between groups (2) IBDQ: 44.22 ± 9.79 to 47.23 ± 9.24 (p = 0.134) vs. 43.12 ± 6 to 41.87 ± 14.18 (p = 0.636); p = 0.14 in between groups (3) MDA: 8.33 ± 1.82 to 3.87 ± 1.95 (p < 0.001) vs. 7.88 ± 2.24 to 6.38 ± 2.42 (p = 0.119); p < 0.001 between groups | None reported |

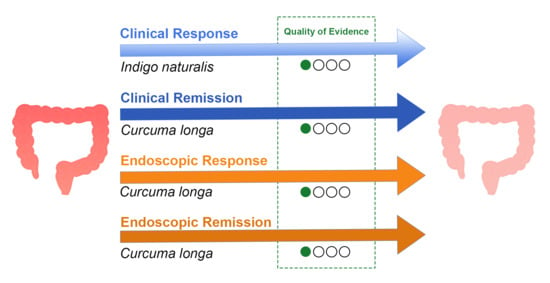

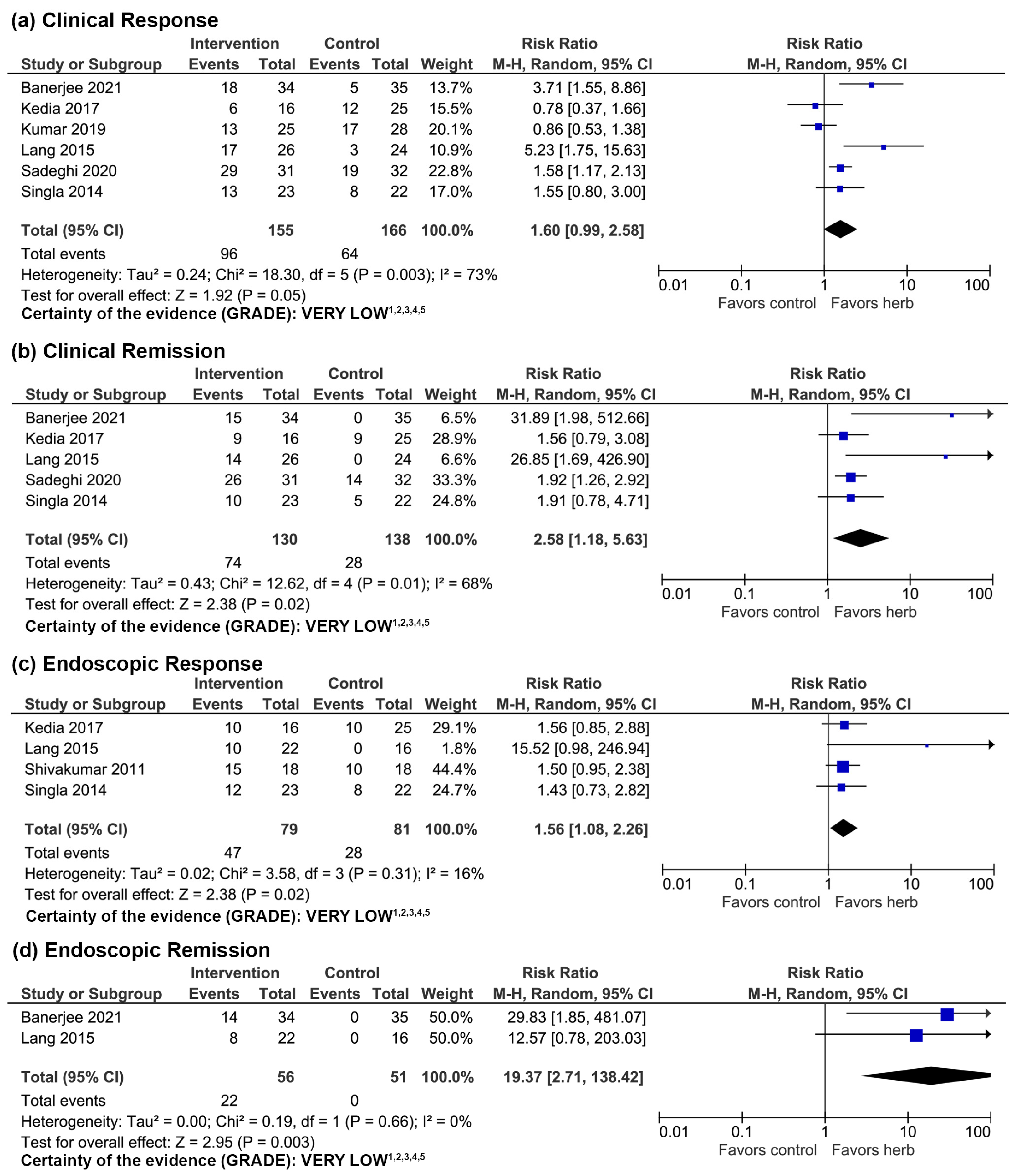

3.1. Curcuma longa

3.1.1. Clinical Evidence

3.1.2. Adverse Events

3.1.3. Quality of Evidence

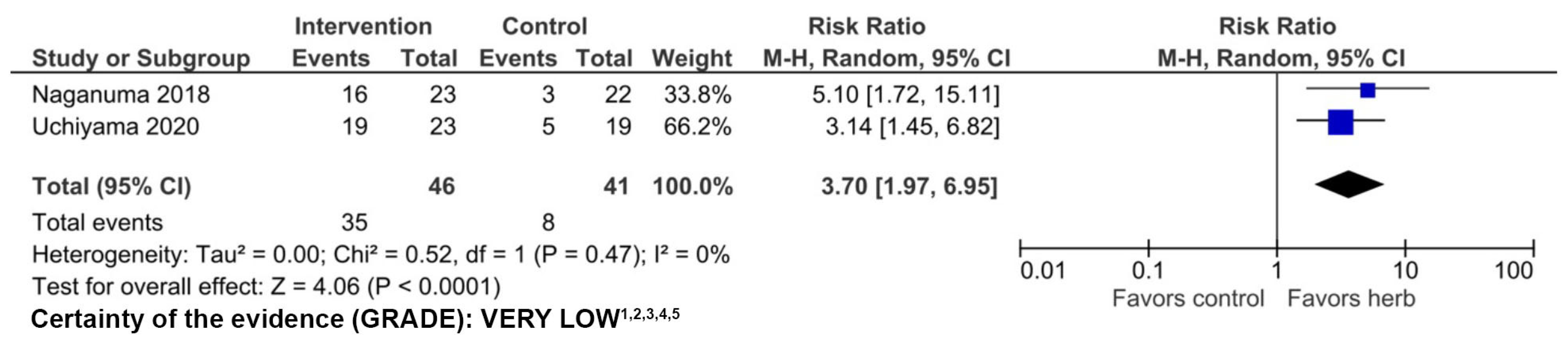

3.2. Indigo naturalis

3.2.1. Clinical Evidence

3.2.2. Adverse Events

3.2.3. Quality of Evidence

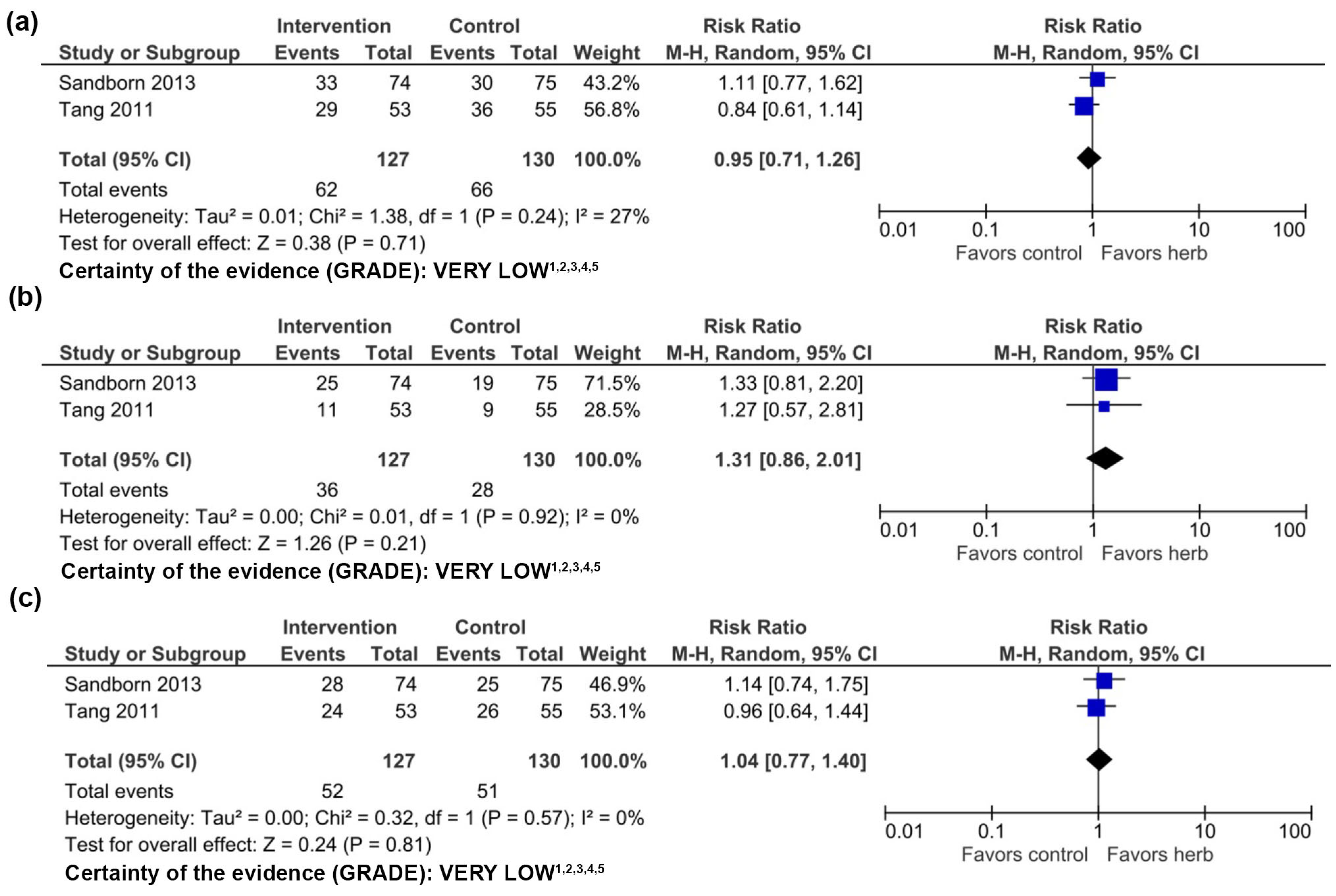

3.3. Andrographis paniculata

3.3.1. Clinical Evidence

3.3.2. Adverse Events

3.3.3. Quality of Evidence

3.4. Aloe vera

3.4.1. Clinical Evidence

3.4.2. Adverse Events

3.4.3. Quality of Evidence

3.5. Arthrospira platenesis

3.5.1. Clinical Evidence

3.5.2. Quality of Evidence

3.6. Boswellia serrata

3.6.1. Clinical Evidence

3.6.2. Adverse Events

3.6.3. Quality of Evidence

3.7. Green Tea

3.7.1. Clinical Evidence

3.7.2. Adverse Events

3.7.3. Quality of Evidence

3.8. Flaxseed

3.8.1. Clinical Evidence

3.8.2. Adverse Events

3.8.3. Quality of Evidence

3.9. Licorice

3.9.1. Clinical Evidence

3.9.2. Adverse Events

3.9.3. Quality of Evidence

3.10. Olive Oil

3.10.1. Clinical Evidence

3.10.2. Adverse Events

3.10.3. Quality of Evidence

3.11. Pistacia lentiscus

3.11.1. Clinical Evidence

3.11.2. Adverse Events

3.11.3. Quality of Evidence

3.12. Plantago major

3.12.1. Clinical Evidence

3.12.2. Adverse Events

3.12.3. Quality of Evidence

3.13. Punica granatum

3.13.1. Clinical Evidence

3.13.2. Adverse Events

3.13.3. Quality of Evidence

3.14. Rose Oil

3.14.1. Clinical Evidence

3.14.2. Adverse Events

3.14.3. Quality of Evidence

3.15. Saffron

3.15.1. Clinical Evidence

3.15.2. Adverse Events

3.15.3. Quality of Evidence

3.16. Thymus kotschyanus

3.16.1. Clinical Evidence

3.16.2. Adverse Events

3.16.3. Quality of Evidence

3.17. Wheatgrass

3.17.1. Clinical Evidence

3.17.2. Adverse Events

3.17.3. Quality of Evidence

3.18. Zingiber officinale

3.18.1. Clinical Evidence

3.18.2. Adverse Events

3.18.3. Quality of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, L.; Ha, C. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 49, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.P.; LeBlanc, J.-F.; Hart, A.L. Ulcerative colitis: An update. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardo, S.; Altuwaijri, M.; Devlin, S.M.; Seow, C.H. Complementary and alternative medications in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 175628482092755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenstein, M. Ulcerative colitis: Towards remission. Nature 2018, 563, S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algieri, F.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Rodriguez-Cabezas, M.E.; Risco, S.; Ocete, M.A.; Galvez, J. Botanical Drugs as an Emerging Strategy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallinger, Z.R.; Nguyen, G.C. Practices and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of gastroenterologists. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2014, 11, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zezos, P.; Nguyen, G.C. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Around the World. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 46, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Cheifetz, A.S. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 14, 415. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, A.; Kang, N.; Bollom, A.; Wolf, J.L.; Lembo, A. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Is Prevalent Among Patients with Gastrointestinal Diseases. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilsden, R.J.; Verhoef, M.J.; Best, A.; Pocobelli, G. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use by Canadian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results from A National Survey. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 98, 1563–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawsthorne, P.; Clara, I.; Graff, L.A.; Bernstein, K.I.; Carr, R.; Walker, J.R.; Ediger, J.; Rogala, L.; Miller, N.; Bernstein, C.N. The Manitoba Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study: A prospective longitudinal evaluation of the use of complementary and alternative medicine services and products. Gut 2012, 61, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fábián, A.; Rutka, M.; Ferenci, T.; Bor, R.; Bálint, A.; Farkas, K.; Milassin, Á.; Szántó, K.; Lénárt, Z.; Nagy, F.; et al. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Is Less Frequent in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Than in Patients with Other Chronic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, A.; Ebbeskog, B.; Karlen, P.; Oxelmark, L. Inflammatory bowel disease professionals’ attitudes to and experiences of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holleran, G.; Scaldaferri, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Currò, D. Herbal medicinal products for inflammatory bowel disease: A focus on those assessed in double-blind randomised controlled trials. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhorst, J.; Wulfert, H.; Lauche, R.; Klose, P.; Cramer, H.; Dobos, G.J.; Korzenik, J. Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 9, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, R. Induction of clinical response and remission of inflammatory bowel disease by use of herbal medicines: A meta-analysis. WJG 2013, 19, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, R.D.; Barbalho, S.M.; Lima, V.M.; Souza, G.A.; Matias, J.N.; Araújo, A.C.; Rubira, C.J.; Buchaim, R.L.; Buchaim, D.V.; Carvalho, A.C.; et al. Effects of the Use of Curcumin on Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Food 2021, 24, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllidi, A.; Xanthos, T.; Papalois, A.; Triantafillidis, J.K. Herbal and plant therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.C.; Lam, Y.T.; Tsoi, K.K.F.; Chan, F.K.L.; Sung, J.J.Y.; Wu, J.C.Y. Systematic review: The efficacy of herbal therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 38, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, R.; Pal, P.; Penmetsa, A.; Kathi, P.; Girish, G.; Goren, I.; Reddy, D.N. Novel Bioenhanced Curcumin with Mesalamine for Induction of Clinical and Endoscopic Remission in Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-controlled Pilot Study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 55, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, S.; Bhatia, V.; Thareja, S.; Garg, S.; Mouli, V.P.; Bopanna, S.; Tiwari, V.; Makharia, G.; Ahuja, V. Low dose oral curcumin is not effective in induction of remission in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: Results from a randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. WJGPT 2017, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Dutta, U.; Shah, J.; Singh, P.; Vaishnavi, C.; Prasad, K.K.; Singh, K. Impact of curcuma longa on clinical activity and inflammatory markers in patients with active ulcerative colitis: A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, S322–S323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.; Salomon, N.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Kopylov, U.; Lahat, A.; Har-Noy, O.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Cheong, P.K.; Avidan, B.; Gamus, D.; et al. Curcumin in Combination with Mesalamine Induces Remission in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Ulcerative Colitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 1444–1449.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoodi, M.; Mahdiabadi, M.A.; Mokhtare, M.; Agah, S.; Kashani, A.H.F.; Rezadoost, A.M.; Sabzikarian, M.; Talebi, A.; Sahebkar, A. The efficacy of curcuminoids in improvement of ulcerative colitis symptoms and patients’ self-reported well-being: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 9552–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, N.; Mansoori, A.; Shayesteh, A.; Hashemi, S.J. The effect of curcumin supplementation on clinical outcomes and inflammatory markers in patients with ulcerative colitis. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivakumar, V.; Sharonjeet, K.; Dutta, U.; Vaishnavi, K.; Prasad, K.K.; Kochhar, R.; Singh, K. A double blind randomised controlled trial to study the effect of oral Curcumina longa versus placebo in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 30, A37. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, V.; Pratap Mouli, V.; Garg, S.K.; Rai, T.; Choudhury, B.N.; Verma, P.; Deb, R.; Tiwari, V.; Rohatgi, S.; Dhingra, R.; et al. Induction with NCB-02 (curcumin) enema for mild-to-moderate distal ulcerative colitis—A randomized, placebo-controlled, pilot study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naganuma, M.; Sugimoto, S.; Mitsuyama, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshimura, N.; Ohi, H.; Tanaka, S.; Andoh, A.; Ohmiya, N.; Saigusa, K.; et al. Efficacy of Indigo Naturalis in a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, K.; Takami, S.; Suzuki, H.; Umeki, K.; Mochizuki, S.; Kakinoki, N.; Iwamoto, J.; Hoshino, Y.; Omori, J.; Fujimori, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of short-term therapy with indigo naturalis for ulcerative colitis: An investigator-initiated multicenter double-blind clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Targan, S.R.; Byers, V.S.; Rutty, D.A.; Mu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tang, T. Andrographis paniculata Extract (HMPL-004) for Active Ulcerative Colitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Targan, S.R.; Li, Z.-S.; Xu, C.; Byers, V.S.; Sandborn, W.J. Randomised clinical trial: Herbal extract HMPL-004 in active ulcerative colitis—A double-blind comparison with sustained release mesalazine: Randomised clinical trial: Herbal extract HMPL-004 for ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, L.; Feakins, R.M.; Goldthorpe, S.; Holt, H.; Tsironi, E.; De Silva, A.; Jewell, D.P.; Rampton, D.S. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral aloe vera gel for active ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 19, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pica, R.; Cassieri, C.; Unim, H.; Paoluzi, P.; Crispino, P.; Cocco, A.; De Nitto, D.; Paoluzi, N.; Zippi, M. Enema of aloe vera gel for achieving remission in active ulcerative proctosigmoiditis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ital. J. Med. 2021, 15, 56. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, S.; Zobeiri, M.; Feizi, A.; Clark, C.C.T.; Entezari, M.H. The effects of spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) supplementation on anthropometric indices, blood pressure, sleep quality, mental health, fatigue status and quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis: A randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e144720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Parihar, A.; Malhotra, P.; Singh, G.B.; Lüdtke, R.; Safayhi, H.; Ammon, H.P. Effects of Boswellia serrata gum resin in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1997, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dryden, G.W.; Lam, A.; Beatty, K.; Qazzaz, H.H.; McClain, C.J. A Pilot Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of an Oral Dose of (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate–Rich Polyphenon E in Patients with Mild to Moderate Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshedzadeh, N.; Shahrokh, S.; Aghdaei, H.A.; Amin Pourhoseingholi, M.; Chaleshi, V.; Hekmatdoost, A.; Karimi, S.; Zali, M.R.; Mirmiran, P. Effects of flaxseed and flaxseed oil supplement on serum levels of inflammatory markers, metabolic parameters and severity of disease in patients with ulcerative colitis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 46, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshedzadeh, N.; Shahrokh, S.; Chaleshi, V.; Karimi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Zali, M.R. The effects of flaxseed supplementation on gene expression and inflammation in ulcerative colitis patients: An open-labelled randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-W.; Zhang, L. Effect of liquorice decoction combined with mesalazine on serum inflammatory factors and T lymphocyte levels in patients with ulcerative colitis. WCJD 2018, 26, 1879–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morvaridi, M.; Jafarirad, S.; Seyedian, S.S.; Alavinejad, P.; Cheraghian, B. The effects of extra virgin olive oil and canola oil on inflammatory markers and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papada, E.; Forbes, A.; Amerikanou, C.; Torović, L.; Kalogeropoulos, N.; Tzavara, C.; Triantafillidis, J.; Kaliora, A. Antioxidative Efficacy of a Pistacia Lentiscus Supplement and Its Effect on the Plasma Amino Acid Profile in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghizadeh, A.; Davati, A.; Heidarloo, A.J.; Emadi, F.; Aliasl, J. Efficacy of Plantago major seed in management of ulcerative colitis symptoms: A randomized, placebo controlled, clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 44, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, M.; Tavakoli, H.; Khodadoost, M.; Daghaghzadeh, H.; Kamalinejad, M.; Gachkar, L.; Mansourian, M.; Adibi, P. Efficacy of the Punica granatum peels aqueous extract for symptom management in ulcerative colitis patients. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, A.; Shirzad, M.; Taghavi, A.; Fattahi, M.; Ahmadian-Attari, M.; Mohammad Taghizadeh, L.; Rostami Chaijan, M.; Sedigh Rahimabadi, M.; Akrami, R.; Pasalar, M. Efficacy of Rose Oil Soft Capsules on Clinical Outcomes in Ulcerative Colitis: A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. GMJ 2019, 8, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydarian, A.; Kashani, A.H.F.; Masoodi, M.; Aryaeian, N.; Vafa, M.; Tahvilian, N.; Hosseini, A.F.; Fallah, S.; Moradi, N.; Farsi, F. Effects of saffron supplementation on serum inflammatory markers and quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis: A double blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Herbal. Med. 2022, 36, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahvilian, N.; Masoodi, M.; Faghihi Kashani, A.; Vafa, M.; Aryaeian, N.; Heydarian, A.; Hosseini, A.; Moradi, N.; Farsi, F. Effects of saffron supplementation on oxidative/antioxidant status and severity of disease in ulcerative colitis patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazirian, F.; Samadi, S.; Abbaspour, M.; Taleb, A.; Bagherhosseini, H.; Mozaffari, H.M.; Mohammadpour, A.H.; Emami, S.A. Evaluation of the efficacy of Thymus kotschyanus extract as an additive treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Arye, E.; Goldin, E.; Wengrower, D.; Stamper, A.; Kohn, R.; Berry, E. Wheat Grass Juice in the Treatment of Active Distal Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized Double-blind Placebo-controlled Trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikkhah-Bodaghi, M.; Maleki, I.; Agah, S.; Hekmatdoost, A. Zingiber officinale and oxidative stress in patients with ulcerative colitis: A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreedhar, R.; Arumugam, S.; Thandavarayan, R.A.; Karuppagounder, V.; Watanabe, K. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent in the chemoprevention of inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.-P.; Wang, M.-X.; Wu, T.-T.; Liu, D.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Long, J.; Zhao, H.-M.; Zhong, Y.-B. Curcumin Alleviated Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis by Regulating M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization and TLRs Signaling Pathway. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Hanai, H.; Tozawa, K.; Aoshi, T.; Uchijima, M.; Nagata, T.; Koide, Y. Curcumin prevents and ameliorates trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid–induced colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 1912–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.; Wang, J.-Y.; Xiong, F.; Wu, B.-H.; Luo, M.-H.; Yu, Z.-C.; Liu, T.-T.; Li, D.-F.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.-X.; et al. Curcumin ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice by regulating the Treg/Th17 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukil, A.; Maity, S.; Karmakar, S.; Datta, N.; Vedasiromoni, J.R.; Das, P.K. Curcumin, the major component of food flavour turmeric, reduces mucosal injury in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid-induced colitis: Effect of curcumin in mouse colitis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 139, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, S.; Zhou, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, L.; Du, X.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, W.; Wu, J. Curcumin alleviates DSS-induced colitis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammsome activation and IL-1β production. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 104, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Ge, W.; Liu, S.-Q.; Long, J.; Jiang, Q.-Q.; Zhou, W.; Zuo, Z.-Y.; Liu, D.-Y.; Zhao, H.-M.; Zhong, Y.-B. Curcumin Inhibits T Follicular Helper Cell Differentiation in Mice with Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liczbiński, P.; Michałowicz, J.; Bukowska, B. Molecular mechanism of curcumin action in signaling pathways: Review of the latest research. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 1992–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burge, K.; Gunasekaran, A.; Eckert, J.; Chaaban, H. Curcumin and Intestinal Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms of Protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Xu, Y.; Geng, R.; Qiu, J.; He, X. Curcumin Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice Through Regulating Gut Microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2100943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehzad, M.J.; Ghalandari, H.; Nouri, M.; Askarpour, M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin/turmeric supplementation in adults: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cytokine 2023, 164, 156144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabczyk, M.; Nowak, J.; Hudzik, B.; Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska, B. Curcumin and Its Potential Impact on Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, S.; Naganuma, M.; Kiyohara, H.; Arai, M.; Ono, K.; Mori, K.; Saigusa, K.; Nanki, K.; Takeshita, K.; Takeshita, T.; et al. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Oral Qing-Dai in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Single-Center Open-Label Prospective Study. Digestion 2016, 93, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, K.; Mori, D.; Hatanaka, A.; Sawano, T.; Nakatani, J.; Ikeya, Y.; Nishizawa, M.; Tanaka, H. Comparison of the anti-colitis activities of Qing Dai/Indigo Naturalis constituents in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 142, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.-N.; Yu, J.-G.; Zhang, D.-B.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, L.-L.; Li, L.-H.; Wang, Z.; Tang, Z.-S. Indigo Naturalis Ameliorates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Mice by Modulating the Intestinal Microbiota Community. Molecules 2019, 24, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Dai, Y.; Wang, W.; Shi, R.; Wang, Z.; Ding, P.; Lu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Pei, W.; et al. Indigo Naturalis Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis in Rats via Altering Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H.; Choi, Y.Y.; Yang, G.; Cho, I.-H.; Nam, D.; Yang, W.M. Indirubin, a purple 3,2- bisindole, inhibited allergic contact dermatitis via regulating T helper (Th)-mediated immune system in DNCB-induced model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuno, Y.; Torisu, T.; Umeno, J.; Shibata, H.; Hirano, A.; Fuyuno, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; Fujioka, S.; Kawasaki, K.; Moriyama, T.; et al. One-year clinical efficacy and safety of indigo naturalis for active ulcerative colitis: A real-world prospective study. Intest. Res. 2022, 20, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, Y.; Hirano, A.; Torisu, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Fuyuno, Y.; Fujioka, S.; Umeno, J.; Moriyama, T.; Nagai, S.; Hori, Y.; et al. Short-term and long-term outcomes of indigo naturalis treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastro Hepatol. 2020, 35, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiki, J.P.; Andreasson, J.O.; Grimes, K.V.; Frumkin, L.R.; Sanjines, E.; Davidson, M.G.; Park, K.; Limketkai, B. Treatment-refractory ulcerative colitis responsive to indigo naturalis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021, 8, e000813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimatsu, Y.; Naganuma, M.; Sugimoto, S.; Tanemoto, S.; Umeda, S.; Fukuda, T.; Nomura, E.; Yoshida, K.; Ono, K.; Mutaguchi, M.; et al. Development of an Indigo Naturalis Suppository for Topical Induction Therapy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Digestion 2020, 101, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Chen, S.-R.; Chai, L.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Overview of pharmacological activities of Andrographis paniculata and its major compound andrographolide. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, S17–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.-W.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Li, W.-C.; Lin, B.-F. The production of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2 in peritoneal macrophages is inhibited by Andrographis paniculata, Angelica sinensis and Morus alba ethyl acetate fractions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 122, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Iglesias, I.; Lozano, R.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Current uses and knowledge of medicinal plants in the Autonomous Community of Madrid (Spain): A descriptive cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Iglesias, I.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Pharmacological Update Properties of Aloe Vera and its Major Active Constituents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, G.; Jiang, H.; Feng, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, J. Aloe vera mitigates dextran sulfate sodium-induced rat ulcerative colitis by potentiating colon mucus barrier. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, M.Z. Boswellia Serrata, A Potential Antiinflammatory Agent: An Overview. Indian. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 73, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holtmeier, W.; Zeuzem, S.; Prei, J.; Kruis, W.; Böhm, S.; Maaser, C.; Raedler, A.; Schmidt, C.; Schnitker, J.; Schwarz, J.; et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of Boswellia serrata in maintaining remission of Crohn’s disease: Good safety profile but lack of efficacy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-F.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.-K. Gastroprotective Effects of Polyphenols against Various Gastro-Intestinal Disorders: A Mini-Review with Special Focus on Clinical Evidence. Molecules 2021, 26, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalho, S.M.; Bosso, H.; Salzedas-Pescinini, L.M.; de Alvares Goulart, R. Green tea: A possibility in the therapeutic approach of inflammatory bowel diseases? Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oz, H.S.; Chen, T.; de Villiers, W.J.S. Green Tea Polyphenols and Sulfasalazine have Parallel Anti-Inflammatory Properties in Colitis Models. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, T.; Goto, S.; Monira, P.; Isemura, M.; Nakamura, Y. Anti-Inflammatory & Anti-Allergy Agentsin Medicinal Chemistry. Available online: https://benthamscience.com/journal/2/indexing-agency (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Geagea, A.G.; Rizzo, M.; Eid, A.; Hussein, I.H.; Zgheib, Z.; Zeenny, M.N.; Jurjus, R.; Uzzo, M.L.; Spatola, G.F.; Bonaventura, G.; et al. Tea catechins induce crosstalk between signaling pathways and stabilize mast cells in ulcerative colitis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 865–877. [Google Scholar]

- Barbalho, S.M.; de Alvares Goulart, R.; Quesada, K.; Bechara, M.D. Inflammatory bowel disease: Can omega-3 fatty acids really help? Ann. Gastroenterol. 2016, 29, 37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palla, A.H.; Iqbal, N.T.; Minhas, K.; Gilani, A.-H. Flaxseed extract exhibits mucosal protective effect in acetic acid induced colitis in mice by modulating cytokines, antioxidant and antiinflammatory mechanisms. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 38, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Mbodji, K.; Coëffier, M.; Ziegler, F.; Bounoure, F.; Chardigny, J.-M.; Skiba, M.; Savoye, G.; Déchelotte, P.; et al. An α-Linolenic Acid-Rich Formula Reduces Oxidative Stress and Inflammation by Regulating NF-κB in Rats with TNBS-Induced Colitis. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Wang, L.; Yuan, B.; Liu, Y. The Pharmacological Activities of Licorice. Planta Med. 2015, 81, 1654–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larussa, T.; Imeneo, M.; Luzza, F. Olive Tree Biophenols in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: When Bitter is Better. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papalois, A.; Gioxari, A.; Kaliora, A.C.; Lymperopoulou, A.; Agrogiannis, G.; Papada, E.; Andrikopoulos, N.K. Chios Mastic Fractions in Experimental Colitis: Implication of the Nuclear Factor κB Pathway in Cultured HT29 Cells. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 974–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedoussis, G.V.Z.; Kaliora, A.C.; Psarras, S.; Chiou, A.; Mylona, A.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Andrikopoulos, N.K. Antiatherogenic effect of Pistacia lentiscus via GSH restoration and downregulation of CD36 mRNA expression. Atherosclerosis 2004, 174, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, M.B.; Taher, M.; Mutalabisin, M.F.; Amri, M.S.; Abdul Kudos, M.B.; Wan Sulaiman, M.W.A.; Sengupta, P.; Susanti, D. Chemical constituents and medical benefits of Plantago major. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, Y.; Hamedi, S.S.; Kaboli Farshchi, M.; Feyzabadi, Z. Plantago major in Traditional Persian Medicine and modern phytotherapy: A narrative review. Electron. Physician 2018, 10, 6390–6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhakipbekov, K.; Turgumbayeva, A.; Issayeva, R.; Kipchakbayeva, A.; Kadyrbayeva, G.; Tleubayeva, M.; Akhayeva, T.; Tastambek, K.; Sainova, G.; Serikbayeva, E.; et al. Antimicrobial and Other Biomedical Properties of Extracts from Plantago major, Plantaginaceae. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vučić, V.; Grabež, M.; Trchounian, A.; Arsić, A. Composition and Potential Health Benefits of Pomegranate: A Review. CPD 2019, 25, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, H.A.; Farag, M.A. Ongoing and potential novel trends of pomegranate fruit peel; a comprehensive review of its health benefits and future perspectives as nutraceutical. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Long, X.; Yang, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Hou, C. Pomegranate peel polyphenols reduce chronic low-grade inflammatory responses by modulating gut microbiota and decreasing colonic tissue damage in rats fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 8273–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskabady, M.H.; Shafei, M.N.; Saberi, Z.; Amini, S. Pharmacological Effects of Rosa Damascena. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2011, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medicherla, K.; Sahu, B.D.; Kuncha, M.; Kumar, J.M.; Sudhakar, G.; Sistla, R. Oral administration of geraniol ameliorates acute experimental murine colitis by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-κB signaling. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 2984–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashktorab, H.; Soleimani, A.; Singh, G.; Amr, A.; Tabtabaei, S.; Latella, G.; Stein, U.; Akhondzadeh, S.; Solanki, N.; Gondré-Lewis, M.C.; et al. Saffron: The Golden Spice with Therapeutic Properties on Digestive Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharfar, R.; Azimi, R.; Mohseni, M. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of flavonoid-, polyphenol- and anthocyanin-rich extracts from Thymus kotschyanus boiss & hohen aerial parts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6777–6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, H. Essential Oils Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Three Thymus Species. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blažíčková, M.; Blaško, J.; Kubinec, R.; Kozics, K. Newly Synthesized Thymol Derivative and Its Effect on Colorectal Cancer Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamanara, M.; Abdollahi, A.; Rezayat, S.M.; Ghazi-Khansari, M.; Dehpour, A.; Nassireslami, E.; Rashidian, A. Thymol reduces acetic acid-induced inflammatory response through inhibition of NF-kB signaling pathway in rat colon tissue. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durairaj, V.; Hoda, M.; Shakya, G.; Babu, S.P.P.; Rajagopalan, R. Phytochemical screening and analysis of antioxidant properties of aqueous extract of wheatgrass. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, S398–S404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Sela, G.; Cohen, M.; Ben-Arye, E.; Epelbaum, R. The Medical Use of Wheatgrass: Review of the Gap Between Basic and Clinical Applications. MRMC 2015, 15, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.-B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, D.; Hu, X.; Chen, F. Beneficial effects of ginger on prevention of obesity through modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misumi, K.; Ogo, T.; Ueda, J.; Tsuji, A.; Fukui, S.; Konagai, N.; Asano, R.; Yasuda, S. Development of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in a Patient Treated with Qing-Dai (Chinese Herbal Medicine). Intern. Med. 2019, 58, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, M.; Hirooka, K.; Doi, Y. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Associated with the Chinese Herb Indigo Naturalis for Ulcerative Colitis: It May Be Reversible. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, S.; Araki, T.; Okita, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Hamada, Y.; Katsurahara, M.; Horiki, N.; Nakamura, M.; Shimoyama, T.; Yamamoto, T.; et al. Colitis with wall thickening and edematous changes during oral administration of the powdered form of Qing-dai in patients with ulcerative colitis: A report of two cases. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.; Yoon, S.M.; Son, S.-M.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, K.B.; Youn, S.J. Ischemic colitis induced by indigo naturalis in a patient with ulcerative colitis: A case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.T. Herbal Supplements. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 56, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Herb | Author/Year | Random Sequence Generation (Selection Bias) | Allocation Concealment (Selection Bias) | Double Blinding of Participants and Researchers (Performance Bias) | Blinding of Outcome Assessment (Detection Bias) | Incomplete Outcome Data (Attrition Bias) | Selective Reporting (Reporting Bias) | Other Bias | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curcuma longa | Banerjee et al., 2021 [20] | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Limited information regarding allocation concealment. |

| Kedia et al., 2017 [21] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low | High attrition rate in both groups, resulting in uneven number of participants completing study. | |

| Kumar et al., 2019 [22] | Low | Unclear | Low | High | High | Unclear | Unclear | Only abstract available with limited details. Small sample size and did not specify how many participants in each group. | |

| Lang et al., 2015 [23] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Limited information regarding blinding of outcome concealment. | |

| Masoodi et al., 2018 [24] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Limited information regarding blinding of outcome assessment. | |

| Sadeghi et al., 2020 [25] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Limited information regarding blinding of outcome assessment. | |

| Shivakumar et al., 2011 [26] | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Only abstract available with limited details. | |

| Singla et al., 2014 [27] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Limited information regarding blinding of outcome assessment. States that adverse events were documented, but are not described. | |

| Indigo naturalis | Naganuma et al., 2018 [28] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Many patients in placebo group discontinued study resulting in lower clinical response rate. Trial terminated early due to external reasons. |

| Uchiyama et al., 2020 [29] | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Blinding and allocation concealment not discussed. | |

| Andrographis paniculata | Sandborn et al., 2013 [30] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Block randomization schedule was utilized; however, it is not specified whether outcome assessment was performed with blinding. Did not specify adverse events that resulted in 16 people discontinuing study drug. Limitations not mentioned. |

| Tang et al., 2013 [31] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | ≥20% attrition rate in placebo group. Limitations not mentioned. | |

| Aloe vera | Langmead et al., 2004 [32] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low | ≥20% attrition rate in both groups; reported change in histologic score and SCCAI as statistically significant, although not a clear outcome. |

| Pica et al., 2021 [33] | High | High | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Unclear | Only abstract available. Reported 44 study participants, but only reported data for 14 participants. Study outcomes not clear. | |

| Arthrospira platensis | Moradi et al., 2021 [34] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Per protocol analysis used. |

| Boswellia serrata | Gupta et al., 1997 [35] | High | Unclear | High | Unclear | High | High | High | Reported 50 study participants and no dropouts but only reported data for 42 participants. Non-randomized study drug allocation. Small sample size with >4:1 intervention–placebo ratio. Study outcomes unclear. Likely inadequately powered. |

| Green tea | Dryden et al., 2013 [36] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | High | Small sample size with 4:1 intervention–placebo ratio; likely inadequately powered. |

| Flaxseed | Morshedzadeh et al., 2019 [37] | Low | High | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | No allocation concealment or double blinding because this was an open-label study. |

| Morshedzadeh et al., 2021 [38] | Low | High | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | No allocation concealment or double blinding because this was an open-label study. | |

| Licorice | Sun et al., 2018 [39] | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Only abstract available, so limited information provided. Only p-values reported. |

| Olive oil | Morivaridi et al., 2020 [40] | Low | High | High | Low | High | Low | Low | Single-blinded crossover trial. No discussion of subject blinding. Carryover and period effects reported. Proportion of disease activity states (remission vs. active disease) not reported. Per protocol analysis used. |

| Pistacia lentiscus | Papada et al., 2018 [41] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Small sample size and unclear whether outcomes were blinded. |

| Plantago major | Baghizadeh et al., 2021 [42] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Small sample size and moderate attrition rate in both groups. |

| Punica granatum | Kamali et al., 2015 [43] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Uneven attrition rate and use of per protocol analysis, although it is reported that those who discontinued the study were not significantly different regarding demographics or symptoms when compared to those who completed the study. |

| Rose oil | Tavakoli et al., 2019 [44] | Low | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | High attrition rate (30%). |

| Saffron | Heydarian et al., 2022 [45] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear whether outcome assessors were blinded. |

| Tahvilian et al., 2020 [46] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear whether outcome assessors were blinded. | |

| Thymus kotschyanus | Vazirian et al., 2022 [47] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | High | High | High | Uneven attrition rate after randomization. Unclear if intention to treat or per protocol analysis used. Significant baseline difference in SIBDQ may influence outcomes. |

| Wheat grass | Ben-Arye et al., 2002 [48] | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | 6/11 patients receiving wheatgrass believed they were receiving wheatgrass, while 2/12 patients receiving placebo believed they were receiving wheatgrass which raises concern regarding blinding of participants. |

| Zingiber officinale | Nikkhah-Bodaghi et al., 2019 [49] | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear whether outcome assessors were blinded. No significant differences in baseline characteristics between both groups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iyengar, P.; Godoy-Brewer, G.; Maniyar, I.; White, J.; Maas, L.; Parian, A.M.; Limketkai, B. Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16070934

Iyengar P, Godoy-Brewer G, Maniyar I, White J, Maas L, Parian AM, Limketkai B. Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2024; 16(7):934. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16070934

Chicago/Turabian StyleIyengar, Preetha, Gala Godoy-Brewer, Isha Maniyar, Jacob White, Laura Maas, Alyssa M. Parian, and Berkeley Limketkai. 2024. "Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 16, no. 7: 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16070934

APA StyleIyengar, P., Godoy-Brewer, G., Maniyar, I., White, J., Maas, L., Parian, A. M., & Limketkai, B. (2024). Herbal Medicines for the Treatment of Active Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 16(7), 934. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16070934