1. Introduction

In 2022, the United States (U.S.) encountered a severe shortage of infant formula with a recall initiated by Abbott Nutrition, one of the largest U.S. infant formula manufacturers that supplies 40% of the nation’s infant formula [

1]. Abbott recalled multiple brands of its powdered formula products due to bacterial contamination from

Cronobacter sakazakii [

2]. Additionally, Abbott also voluntarily closed one of the country’s largest manufacturing facilities in Michigan, which was linked to the contamination [

3]. These events were exacerbated by supply chain disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic, along with restrictive trade and tariff policies in the U.S. that led to a reduction of available infant formula [

4]. By the end of May 2022, the shortage reached its height, with a national out-of-stock rate for infant formula as high as 90% in several states [

5] which left millions of parents to face uncertainty in safely feeding their infants [

6,

7]. In response, the U.S. government introduced “Operation Fly” to assist families in accessing safe imported infant formulas. Under Operation Fly, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the General Services Administration (GSA) partnered with other nations that meet U.S. health and safety standards to import infant formula to the U.S.

The 2022 infant formula shortage was particularly challenging for vulnerable populations such as families from low-income communities that participate in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) [

1] that heavily depend on infant formula (consuming >50% of U.S.-produced formula) [

8,

9] and infants in need of specialty formulas due to medical or other conditions [

10]. Infants that require specialty formulas due to metabolic or medical conditions such as inborn error of metabolism, low birth weight or other medical or dietary conditions represent approximately 6% of infants that use infant formula in the U.S. [

11].

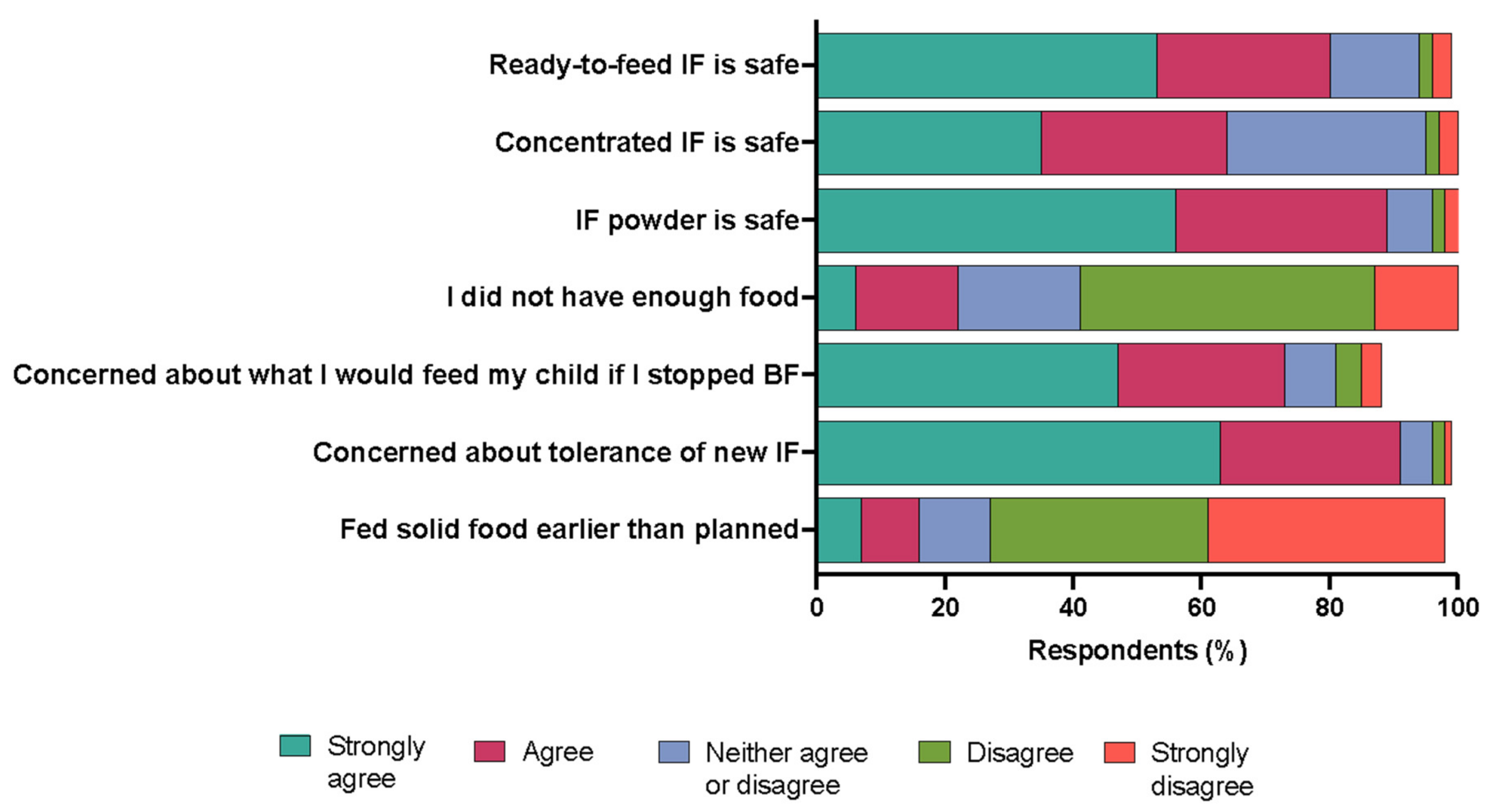

Due to the inaccessibility of infant formula, healthcare providers expressed concerns that parents would resort to unsafe infant feeding practices, contrary to recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Such unsafe infant feeding practices include: (1) diluting formula with water [

12]; (2) preparing homemade infant formula [

13]; (3) introducing cow’s milk before one year of age [

14]; and (4) using human milk from informal sharing [

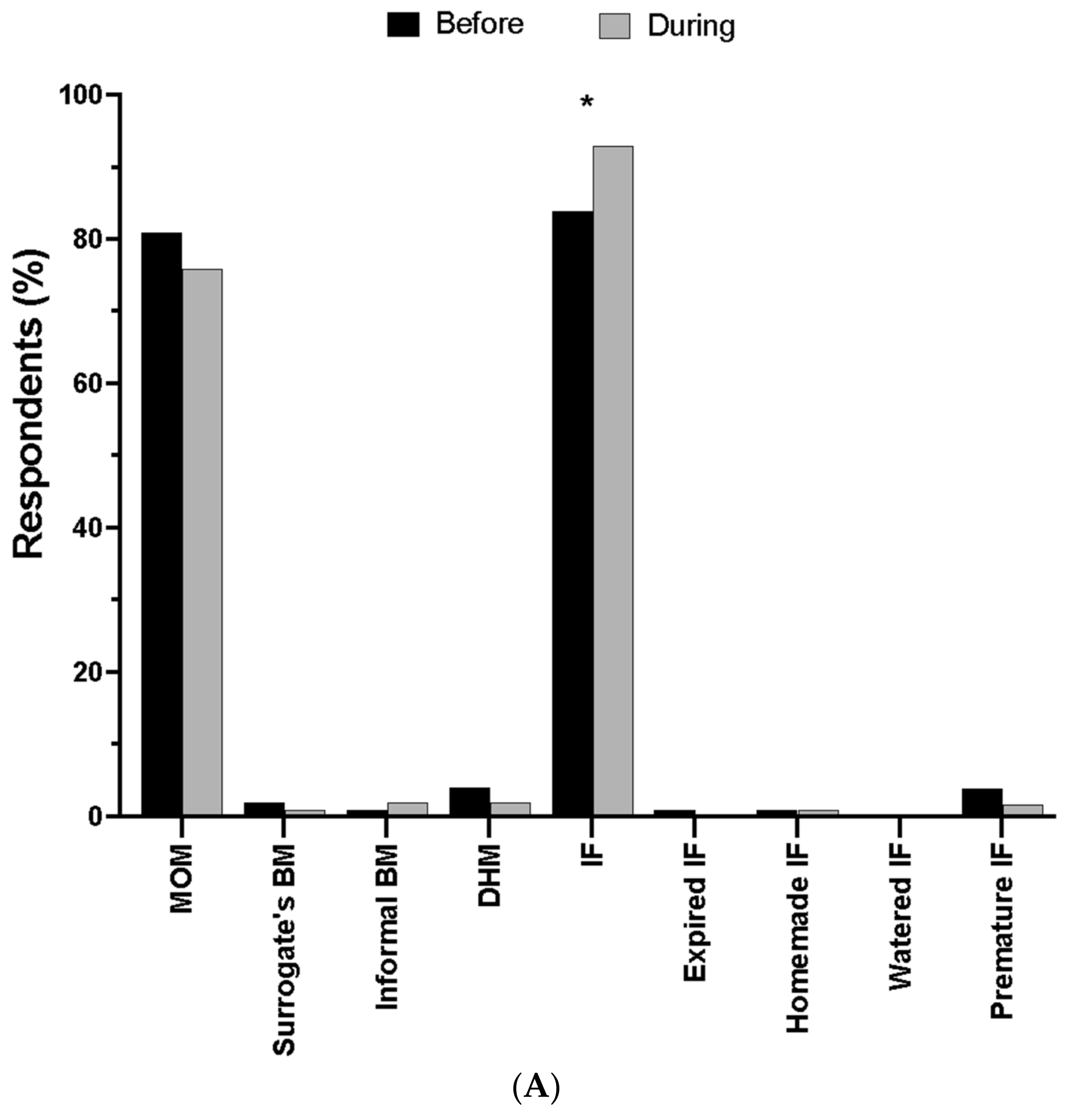

15]. In a recent prospective cross-sectional study of parents predominantly from low-income communities, the percent of individuals that used at least one unsafe infant feeding practice increased from 8% before to 48.5% during the 2022 infant formula shortage. Specifically, the percent of parents that reported infant feeding practices before and during the infant formula shortage significantly increased 5% to 26% for use of human milk from informal sharing and 2% to 29% for use of watered-down infant formula [

16]. These unsafe infant feeding practices increase the health and safety risks of infants who depend on infant formula exclusively or as a supplement to human milk.

To date, no studies have reported the impact of the 2022 infant formula shortage on parental consumer behaviors, infant health or quality of life outcomes or breastfeeding outcomes. The purpose of this study was to identify infant feeding practices, health and quality of life outcomes during the 2022 infant formula shortage. We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis and needs assessment in families from middle-high-income communities and reported a high percentage of infants who required specialty formulas. The goal of this study was to identify areas within regulatory and healthcare policies and programs that could improve the resiliency of the infant food system and prevent a future infant-feeding crisis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Design

Parents who were signed up with the Bobbie Infant Formula (U.S.) listserv and agreed to be contacted for future research purposes were emailed an invitation to participate in an anonymous, cross-sectional, electronic survey. Individuals who met all study criteria completed the survey between 18 December 2022 and 31 January 2023. The first one hundred individuals who completed the survey received a USD 50 electronic gift card. Individuals were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) were 18 years old or older; (2) lived with their infants in the U.S. in May 2022; (3) were the parent of an infant aged 6 months or younger in May 2022; (4) their infant consumed some amount of infant formula before the May 2022 shortage; (5) experienced challenges with feeding their infant because of the infant formula shortage in May 2022; and (6) agreed that only one parent of one baby from the same household would complete the survey. The study was approved by the UC Davis Institutional Review Board (IRB ID: 1920147).

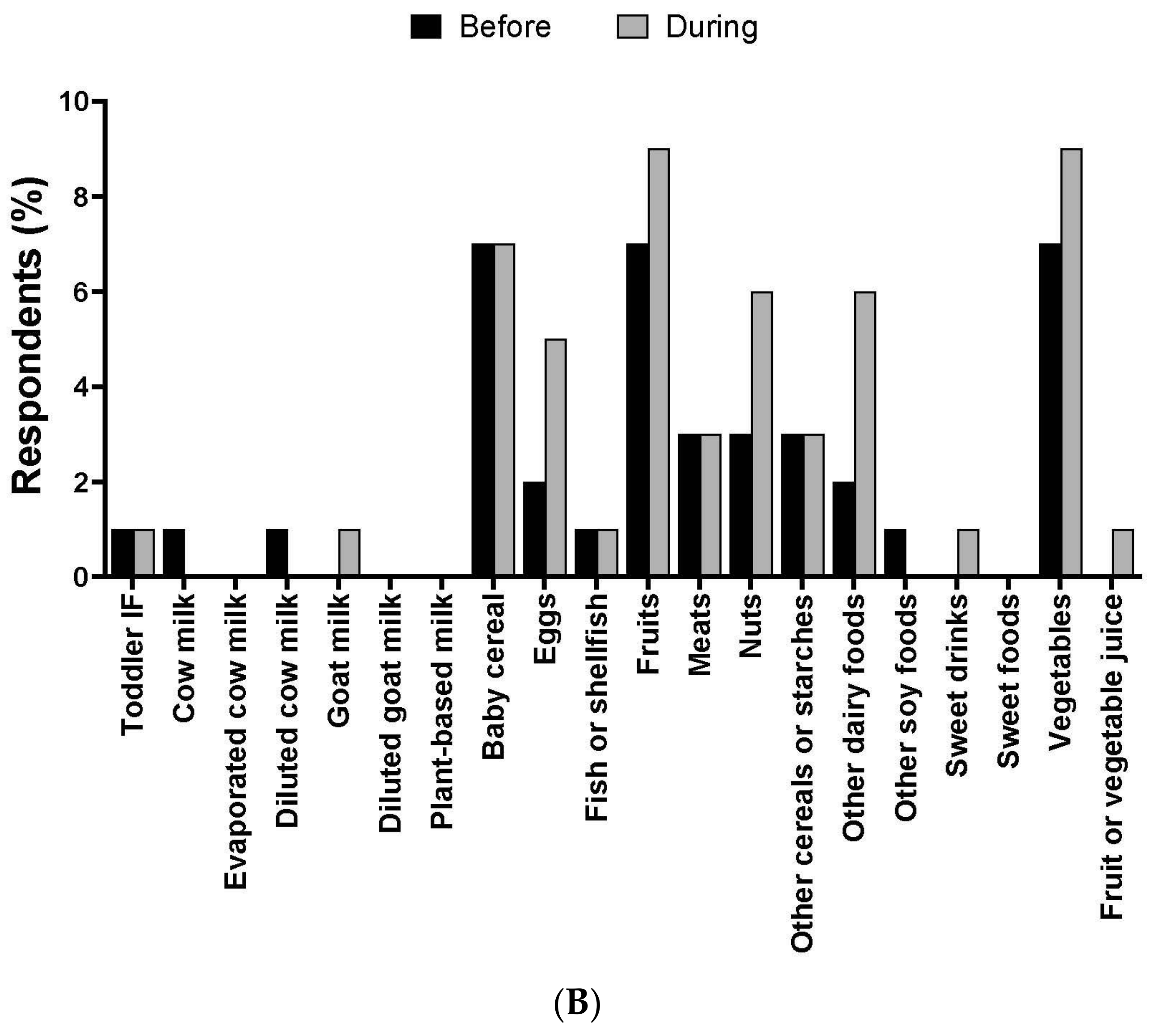

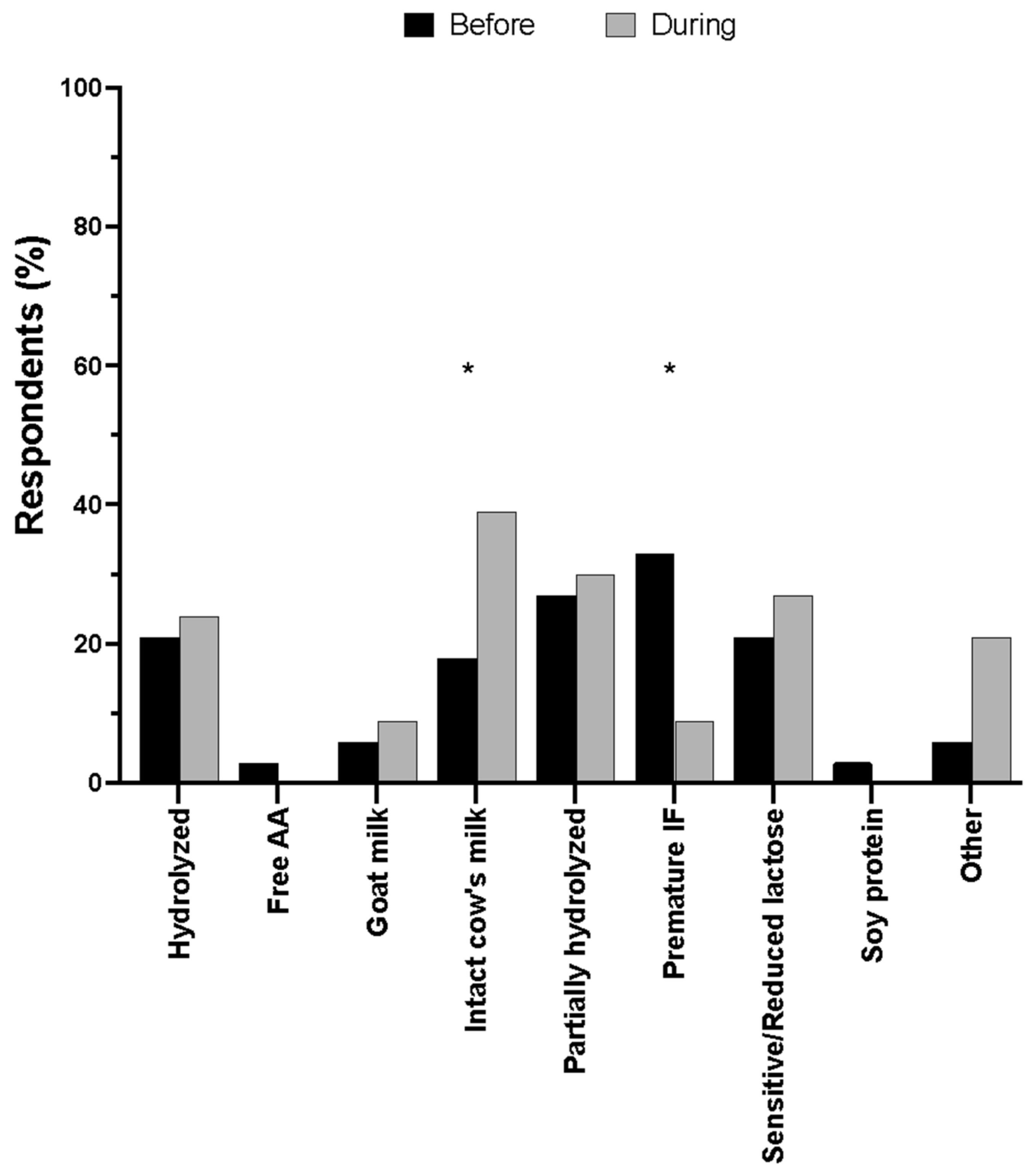

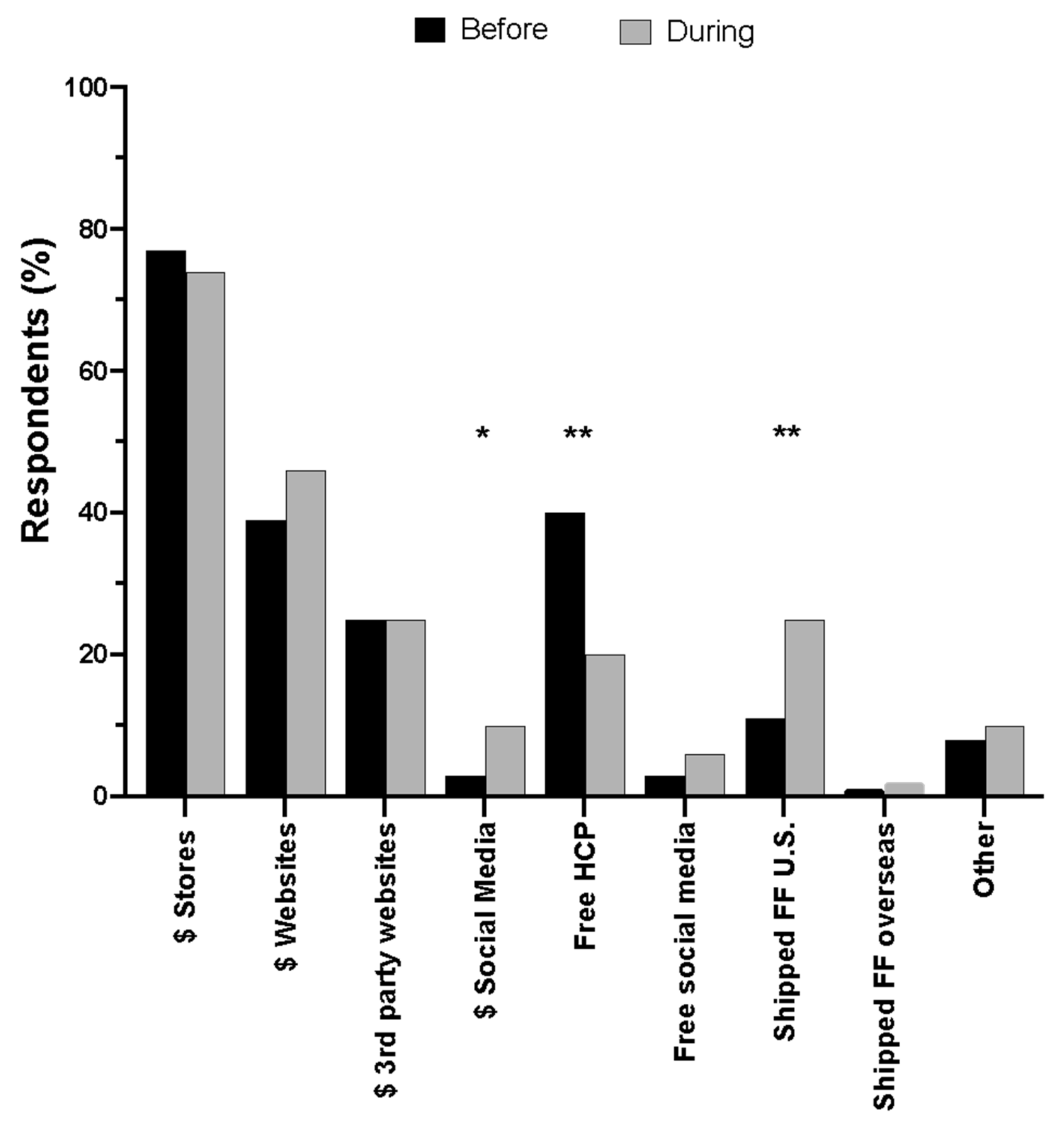

The online survey was created in Qualtrics 2022 (Provo, UT, USA) and consisted of ninety-four unique questions. Participants answered yes/no, multiple choice, rating on a sliding scale (0 to 10) and open-ended questions. The survey contained questions about demographics, infant feeding practices, experiences and sentiments in response to the infant formula shortage. Participants were asked what their infants typically ate over a 7-day period right before and a 7-day period during the infant formula shortage. Moreover, the use of human milk from informal sharing, homemade infant formula, watered-down formula and expired infant formula were aggregated into a single variable named “unsafe infant feeding practices” for a 7-day period right before and a 7-day period during the most challenging time of the shortage.

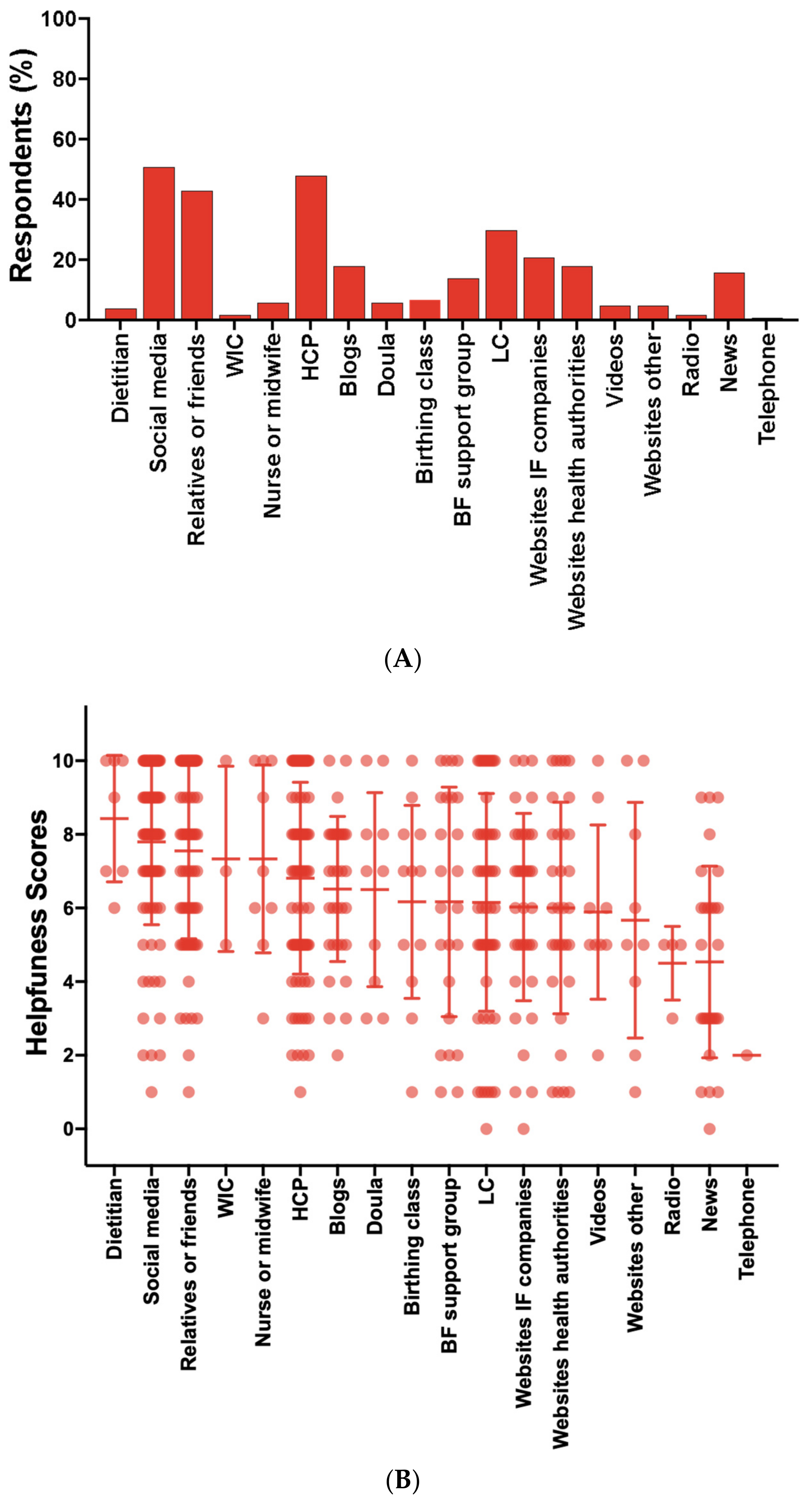

Participants were asked to select resources that provided guidance or support in feeding their infants during the shortage. Participants were also asked to rate on a sliding scale from 0 to 10 how helpful a list of resources “have been” with providing guidance or support to feed their infants or to select “non-applicable” if they did not receive any help from the listed resources. Infant feeding sources and resources used in this survey were adapted from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II) [

17] which differentiated lactation consultants from other healthcare providers and included up-to-date online resources such as social media and blogs.

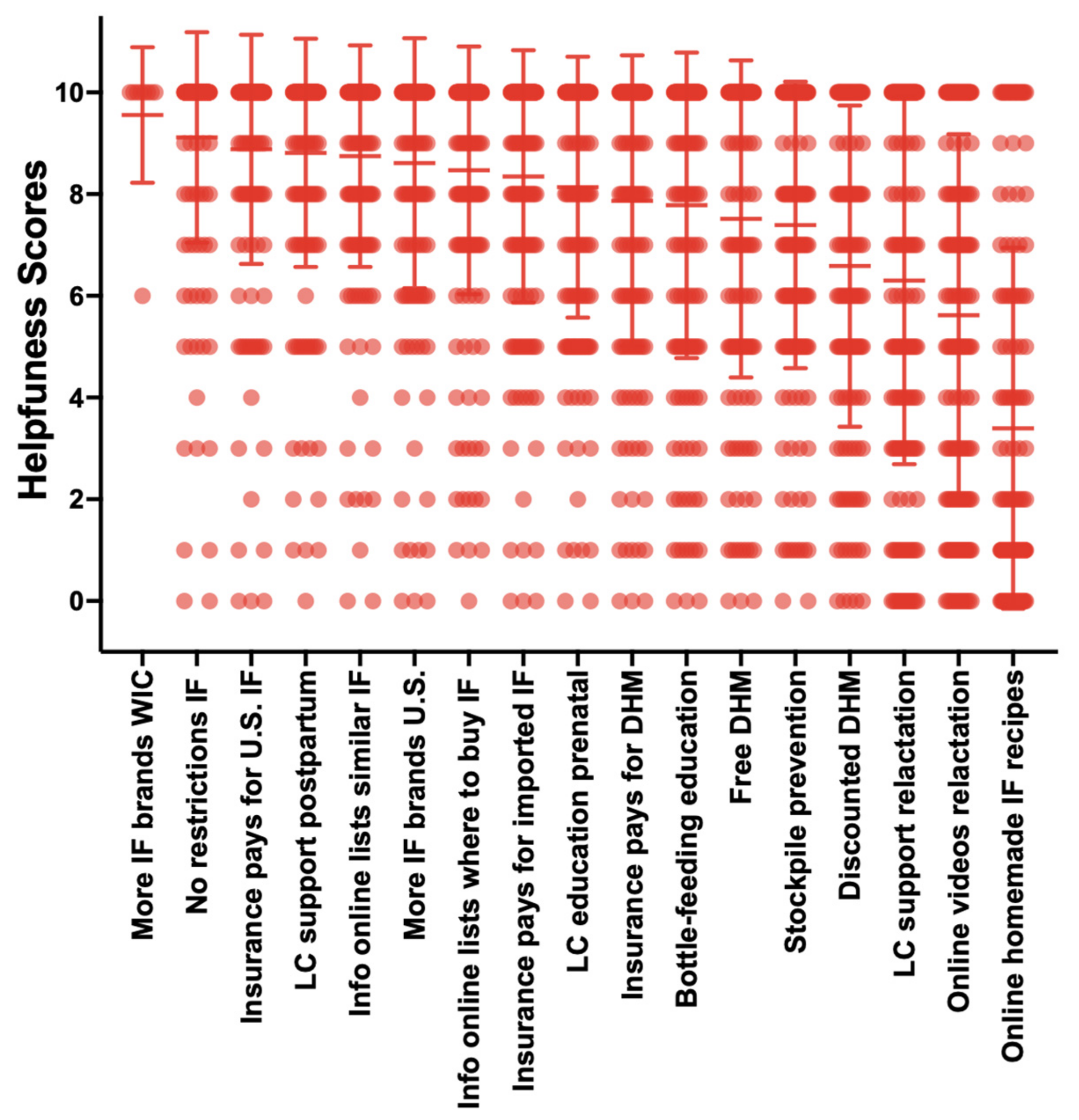

Participants were prompted to rate on a sliding scale ranging from 0 to 10 how helpful a list of activities “would be” in helping families feed their infants in the “near future” or to select “non-applicable” if uncertain. These activities were compiled from comments posted on several multiple social media outlets (Reddit, Facebook, Twitter) by parents during the peak of the 2022 infant formula shortage. The survey used in this study is available as

Supplementary File S1.

2.2. Data Validation

To ensure the reliability of the data collected from the survey and that it was not completed in duplicate by the same individuals, individuals completed two surveys. The first survey was used for screening and prompted individuals from the Bobbie Infant Formula listserv to answer questions about their eligibility. Individuals who met all eligibility criteria were emailed the cross-sectional survey and were required to use the same email addresses entered in the screening survey. The cross-sectional survey excluded individuals with the same email addresses. Only data or completed surveys were used in the statistical analyses.

2.3. Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 and figures were created in GraphPad PRISM v.10.1.2. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Bonferroni-adjusted p-values for multiple comparisons are reported herein. Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, ranges, frequencies, and percentages are reported for demographics, breastfeeding experience, infant feeding practices, consumer behavior, infant outcomes, use of and sentiments about resources and sentiments about future activities that could help families feed their infants in the future.

To understand how infant feeding changed in response to the infant formula crisis, parents were asked what their infants typically ate over a 7-day period right before and a 7-day period during the most challenging time of the infant formula shortage. Parents were also asked how they obtained formula before and during the shortage. Data were treated as binary (yes/no) responses and the McNemar test was used to determine if there were differences for each item before and during the infant formula shortage.

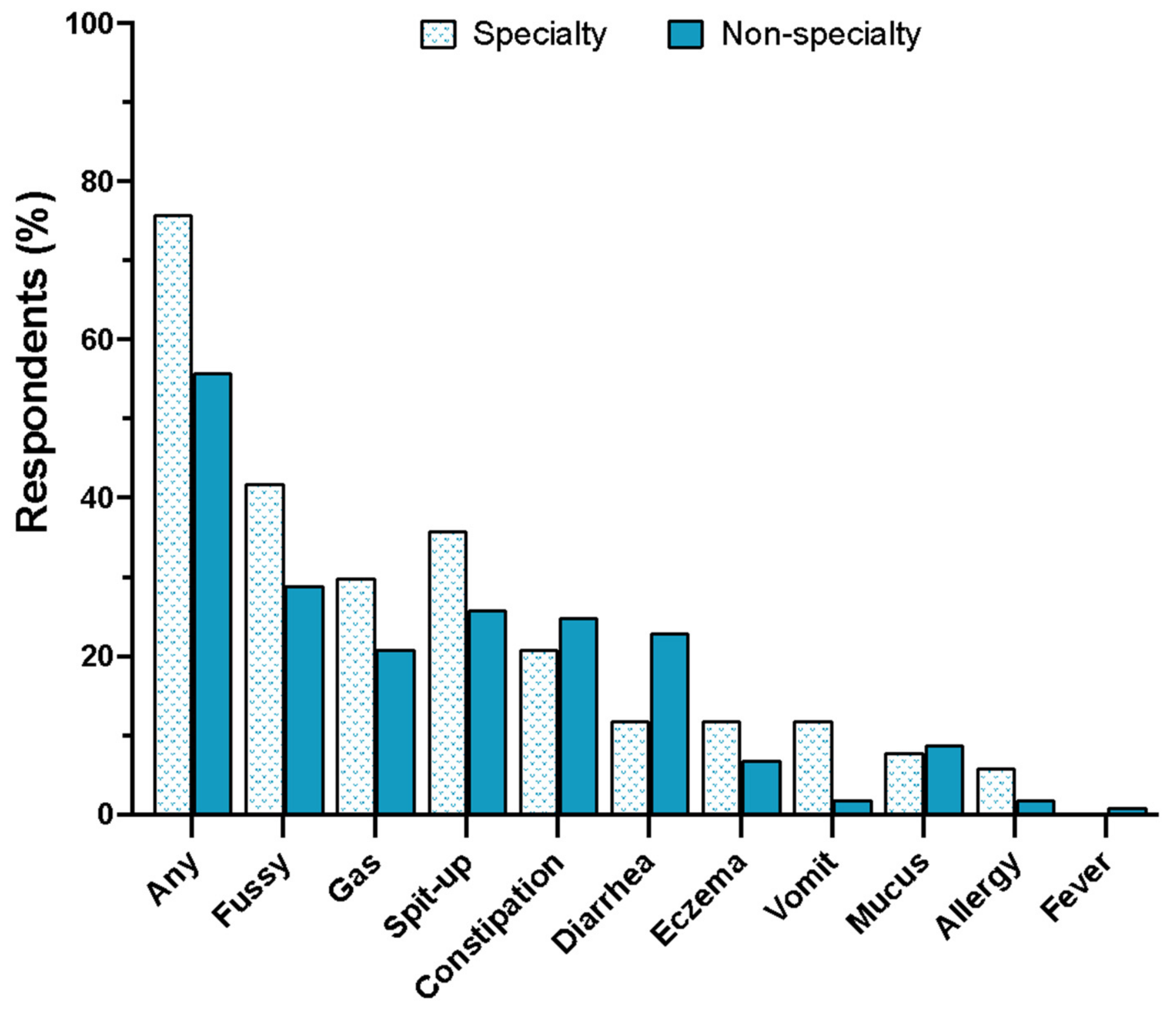

Parents were asked if their infants experienced any problems in response to changing infant formulas during the shortage. Parents selected problems from a list which were treated as binary (yes/no) responses and Pearson chi-square, 2-sided test and phi correlation were used to determine differences and their effect sizes, respectively, in the number of individuals whose infants experienced problems based on their requirement for specialty formulas (vs. no requirement for specialty formulas).

The survey asked parents to choose all applicable options from a list of nineteen resources that provided guidance or support in feeding their infants during the infant formula shortage. Parents who selected “yes” to using any of the nineteen resources were asked to rate on a scale 0–10 how helpful those resources “have been” in providing guidance or support in feeding their infants during the infant formula shortage. Participants were also asked to rate on a scale 0–10 how helpful they think seventeen activities “would be” in helping families feed their babies in the “near future”.

This study also collected qualitative data and prompted parents to offer open responses about how they dealt with the infant formula shortage and the actions they feel should be taken by health authorities, food companies and the government that could help them feed their infants during this crisis and prevent future crises. Open-ended responses were searched for repetition in 5% or more of respondents and reduced to thirty-eight words, themes or key phrases shown in

Table S1. Canva

® 2023 version 1.82.0 was used to manually generate a word cloud of terms for which font size and color are proportional to the frequency of repeated words, themes or key phrases.

4. Discussion

The 2022 infant formula shortage was an unprecedented infant-feeding crisis that led to nationwide food and nutrition insecurity in our most vulnerable population [

7]. This study used a semi-structured questionnaire to investigate infant-feeding practices, parents’ consumer behaviors and infant outcomes in response to the shortage to identify areas within government, regulatory and healthcare systems and policies that could result in a resilient infant food system.

The use of unsafe infant-feeding practices was low in this population and did not change in response to the infant formula shortage. These findings contrast with Cernioglo et al. who reported a significant increase in the use of any unsafe infant-feeding practice from 8% before to 50% during the infant formula shortage [

16]. The differences in the use of unsafe infant-feeding practices between Cernioglo et al. and our study may reflect the differences between the two populations’ socioeconomic statuses and are supported by Marino et al., who reported higher use of unsafe infant-feeding practices by families from lower-income compared with higher-income communities [

18].

While the use of cow milk, goat milk and alternative milk beverages was low (<1%) and did not change, other complementary foods such as baby cereal were used by 7% of parents before and during the shortage, and the use of other dairy such as yogurt increased from 2% before to 6% during the shortage. These data align with a cross-sectional analysis by Marino and co-workers showing 10% of infant formula users added cereal to formula and 7% fed their infants with solid foods instead of feeding infant formula [

18].

The use of pasteurized donor human milk was low (2–4%) and did not significantly change in response to the shortage. These results differ from a recent cross-sectional study by DiMaggio and colleagues, which surveyed 2315 individuals and found that 8% of participants reported using donor milk [

19]. However, our data are consistent with a generally low use of pasteurized donor human milk, which is largely reserved for premature and very-low-birthweight infants, in mostly term and healthy infants.

Approximately 80% of infants were combination feeders (mother’s own breast milk and formula) and, unexpectedly, use of infant formula significantly increased during the shortage when out-of-stock rates climbed as high as 90% in some states. The unexpected increased use of formula during the shortage in this sample may be explained in part by the use of Operation Fly, increased purchases of infant formula via social media and increased shipments of formula sent from family and friends in the United States. Our observations are consistent with a recent qualitative study that reported white female parents expressed positive feelings for having supportive family members and friends who assisted them to find formula which was not described by any Black or SNAP- or WIC-eligible participants [

20]. Another explanation for the increased use of infant formula during the shortage may be the relatively high rate of stockpiling. About 20% of parents stockpiled infant formula during the shortage with 4 weeks’ worth or more of infant formula at home. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends purchasing no more than a 10-day to 2-week supply of formula to prevent hoarding [

21]. Moreover, women had experienced physical or mental challenges with breastfeeding with 80.5% intending to exclusively breastfeed and nearly 90% did not meet their goals.

Based on consumer behavior assessments, parents experienced burden in navigating the May 2022 infant formula shortage. Approximately 80% of parents switched infant formula types or brands during the shortage, and of these individuals, 87% switched because they could not find the formula they “typically” used. One-third or more of parents switched infant formula brands or types three to five times and over a 24 h period visited four or more stores and traveled more than twenty miles to one store to purchase infant formula. These data are similar to a recent report from an online survey of 1070 U.S. consumers, of which one-third had tried to purchase formula during the May 2022 infant formula shortage and, of those consumers, 30% reported purchasing formula at multiple stores [

22]. Another study by Sylvetsky and colleagues reported that parents spent hours searching for formula by driving from store to store and searching online during the May 2022 infant formula shortage [

20]. These data identify a high burden to parents and potentially those from low-income communities for which transportation and time are barriers in accessing food [

23].

Switching infant formula brands and types reduced infant quality of life, especially in infants that relied on specialty formulas. Approximately 60% of parents who switched formulas reported that their infants had one or more problems in response to switching infant formulas. In a sub-group analysis, the number of infants that experienced problems in response to switching formulas was higher in infants requiring specialty formulas compared with infants that did not. These data may be explained in part by the increased use of intact cow’s milk formula during the shortage. These observations are supported by Marino et al., who found two-thirds of parents whose infants relied on specialty formulas reported difficulties accessing these formulas during the COVID-19 pandemic [

18].

Parents relied on several resources to navigate the infant formula shortage with social media and healthcare providers (50%) as the most used, followed by relatives or friends (43%), and about one-third of parents used a lactation consultant or lactation counselor which was lower than data from the CDC and FDA’s 2006 Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPSII) [

17]. The mean helpfulness scores for these resources were moderate with social media scoring the highest. This is consistent with findings from other studies that highlight social media as a powerful tool for diet and health education and support [

16,

20]. Parents’ mean helpfulness scores for future activities that would facilitate feeding infants in the “near future” included freedom to choose infant formula brands, health insurance coverage for infant formula, online resources describing formula types or brands that meet infants’ unique health needs and free universal prenatal lactation education and postpartum lactation support.

Because exclusive human milk feeding is recommended for infants during the first six months of life, female parents were asked questions about their breastfeeding goals, experience and support. Most (80.5%) female parents planned to exclusively breastfeed their infants, however, 87% did not meet their exclusive breastfeeding goals. These data are fairly consistent with the CDC Breastfeeding Report Card showing most U.S. infants (84.1%) have ever consumed any breast milk but only 25% of infants meet the national recommendations of exclusive breastfeeding through six months of life [

6]. There are several factors that explain why women are unable to meet their breastfeeding goals, from lack of federal paid family and medical leave policies, insufficient flexibility and privacy for mothers to breastfeed or pump while at work to barriers in affording or accessing prenatal lactation education and postpartum lactation support which are not part of standard care [

24,

25,

26].

This is the first report of infant-feeding outcomes and consumer behavior in response to the May 2022 infant formula shortage with different limitations and strengths. The limitations include the study design which was 7–8 months retrospectively and is at risk for high recall errors. This may explain in part the small number of parents reporting use of unsafe infant-feeding practices compared to a more recent cross-sectional study in a similar population [

19]. Second, our target population included parents who subscribed to the Bobbie Infant Formula listserv which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Nearly 80% of respondents were derived from largely White communities with annual household incomes equal to or greater than USD 100,000 and not representative of U.S. families that were severely affected by the infant formula shortage. Notably, our survey failed to capture sufficient responses from individuals who represent families from low-income, Black and Hispanic communities that were hit the hardest by the shortage [

10]. There are also several strengths of this study. First, data from this cross-sectional study were collected from a large sample of parents who resided across the United States which improves the study’s generalizability. Second, nearly 90% of respondents reported being “extremely sure” about their answers regarding their infant’s feeding practices before and during the shortage, demonstrating potentially low recall biases. Additionally, 70% of parents answered the open-response question which suggests high engagement with the survey and a proxy for high-quality data. Finally, the survey collected a combination of quantitative and qualitative data on infant feeding, parental experiences and sentiments and infant outcomes that could identify areas in policy and educational strategies to assist families in averting future infant-feeding crises.

We propose a call to action for government, regulatory, health and workplace policies that prioritize infant-feeding practices that deliver optimal nutrition, safety and food security. First, the U.S. infant formula supply is controlled by U.S. trade and regulatory policies that result in a U.S. infant formula monopoly [

27]. High tariffs on formula thwart the import of infant formula to the U.S. and federal policies that govern the manufacture and labeling of infant formula exclude it from entering the U.S. legally [

4]. Systemic failures that reduce infant formula diversification and support a monopoly inequitably impacted low-income communities such as WIC recipients and nutritionally vulnerable infants [

4]. There is a temporary solution with recent modifications to the Access to Baby Formula Act that became law in February 2024. This amendment to the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 will develop a waiver authority to address emergencies, disasters and supply chain disruptions by ensuring WIC state offices can secure supplies from additional manufacturers outside of their contracts. Yet, this law is a stopgap and prevention of another feeding crisis will depend on systemic changes to healthcare policies that also protect the infant-feeding system with access to banked donor milk and lactation education and support. The accessibility and growth of donor-milk-banking services are hindered in part by a lack of federal public health policies that integrate donor milk banking or regulate its operations. Finally, the U.S. government and healthcare system should commit to implementing policies that prioritize lactation education and support. The suboptimal breastfeeding rates in the U.S. and within low-income communities are a result of a lack of federal paid family and medical leave; the absence of flexibility and privacy for mothers to breastfeed or pump while at work; and difficulty affording lactation services, which are not part of standard care. The future of individual, community and societal health relies on optimal early life nutrition that is resilient and equitable for all.