Ancestry Specific Polygenic Risk Score, Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Primary Objective

2.2. Secondary Objective

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Selection of Participants

2.5. Constructing the PRS and Principal Components for Stratification

2.6. Study Variables

2.7. Data Harmonization

2.8. Food Frequency Questionnaire Assessment from Multiple Studies

2.9. Dietary Patterns Construction from Multiple Studies

2.10. Physical Activity Variable Construction from Multiple Studies

2.11. Statistical Analysis

2.12. Interaction between the PRS, Dietary Patterns, and Physical Activity on ASCVD Risk

2.13. Pathway Analysis of SNPs in the PRS Mapped to Genes

3. Results

3.1. Association of the PRS by Genetic Ancestry

3.2. Descriptive Characteristics by Ancestry

3.3. The PRS Was Associated with ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

3.4. Dietary Patterns Were Associated with ASCVD by Ancestry

3.5. Physical Activity Was Associated with ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

3.6. Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity Combined Effects on ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

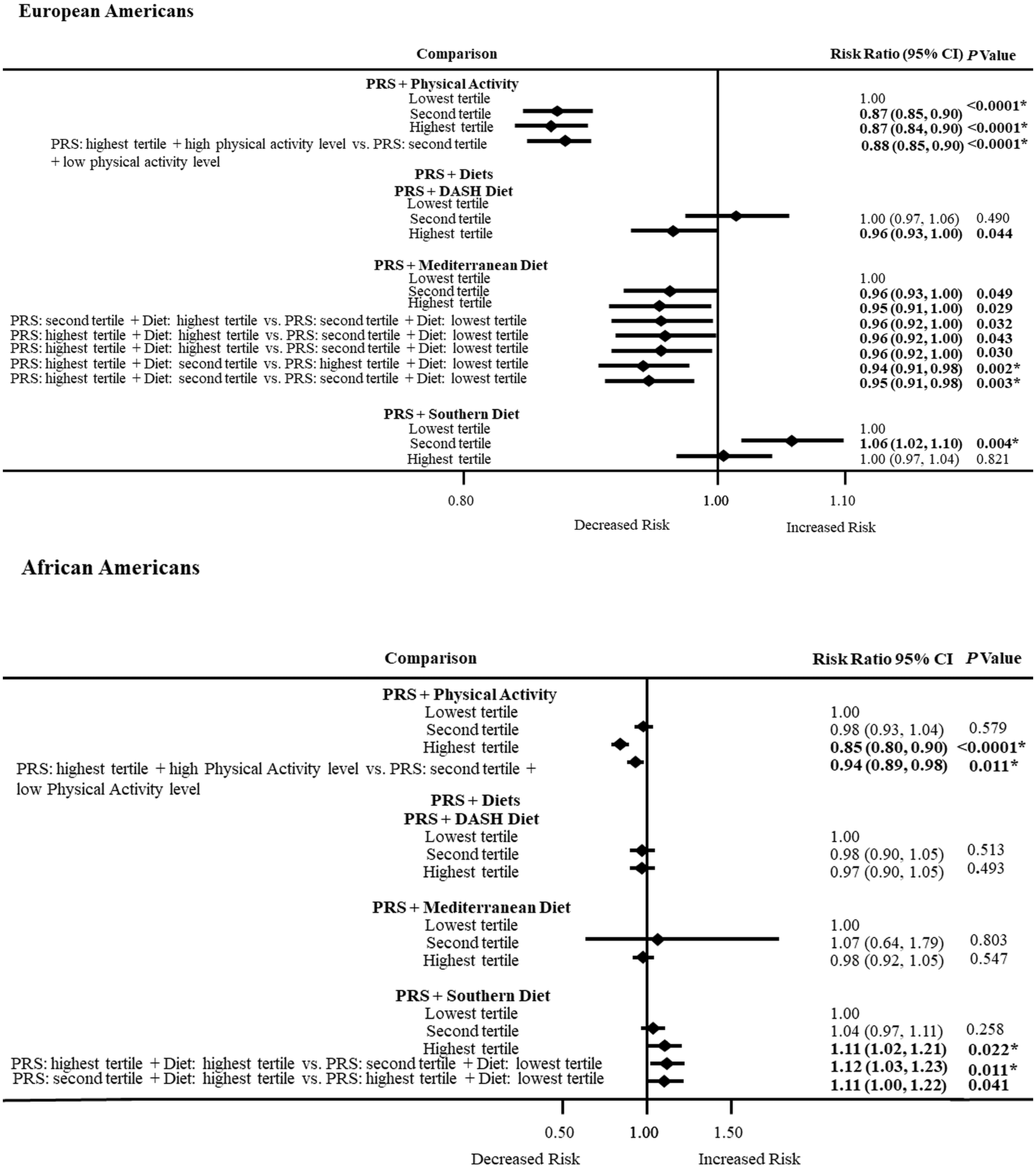

3.7. PRS and Physical Activity or Dietary Patterns Combined Effects on ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

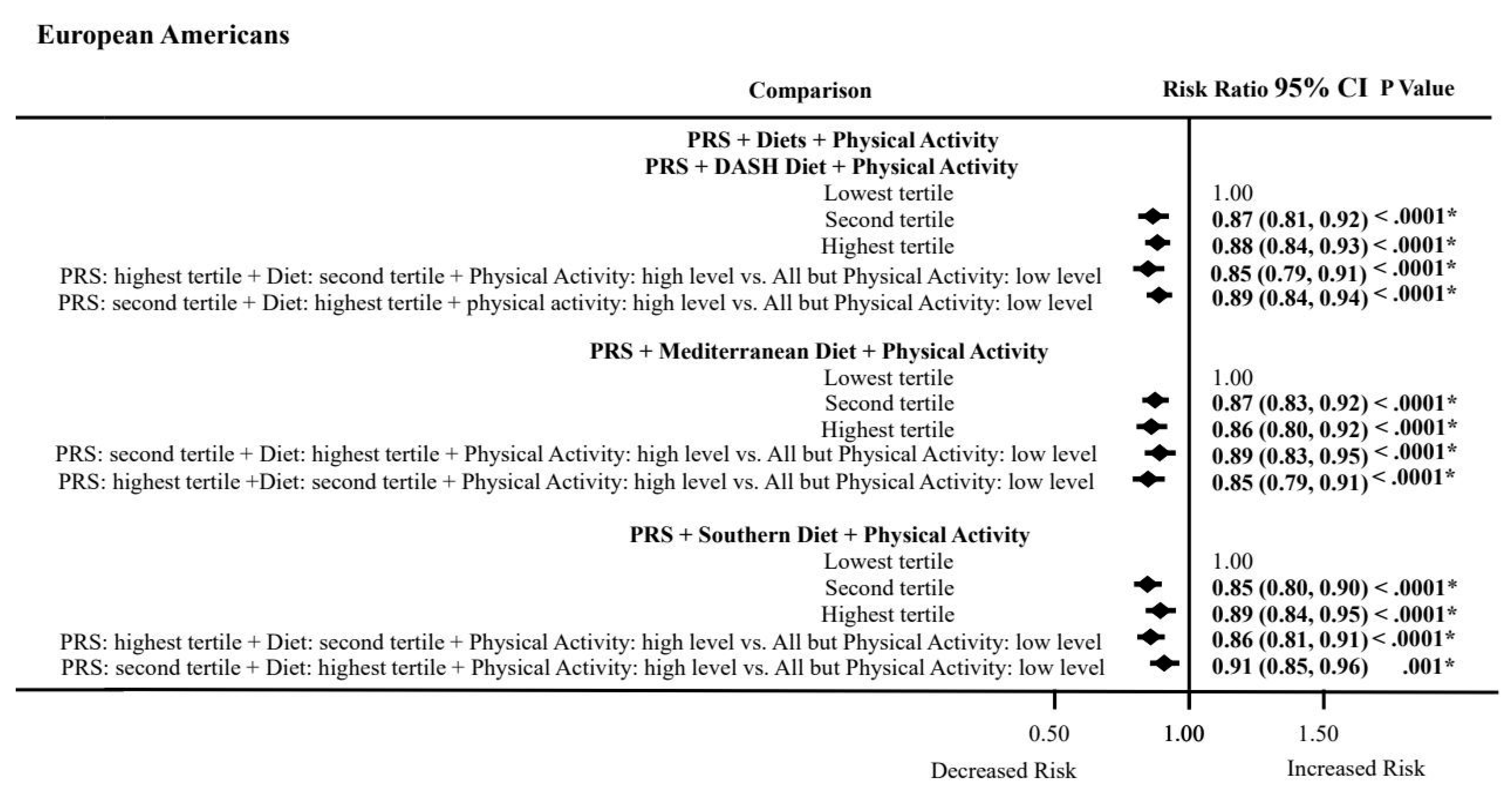

3.8. PRS, Dietary Patterns, and Physical Activity Combined Effects on ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

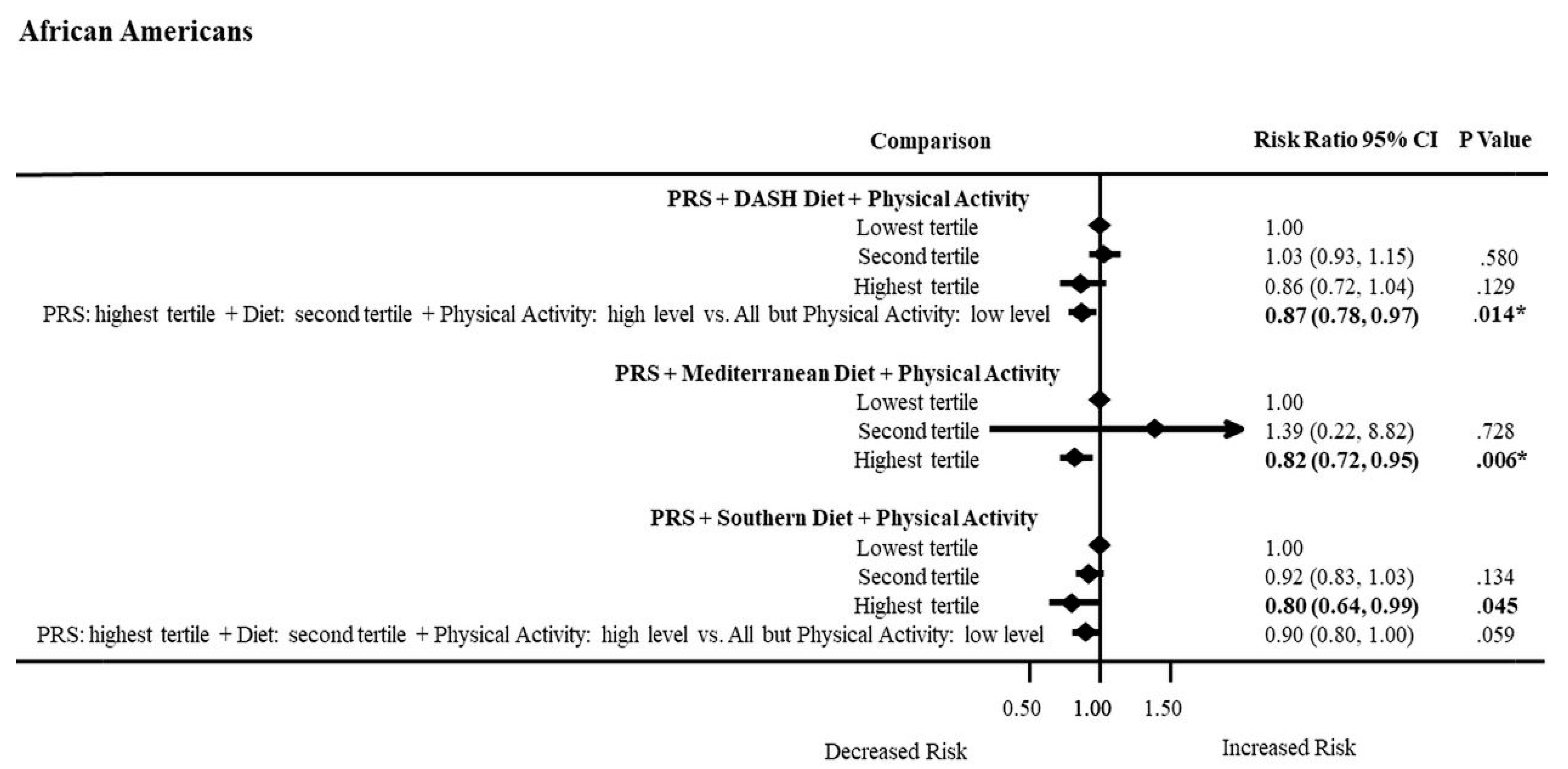

3.9. Interactions of the PRS, Dietary Patterns, and Physical Activity on ASCVD Risk by Ancestry

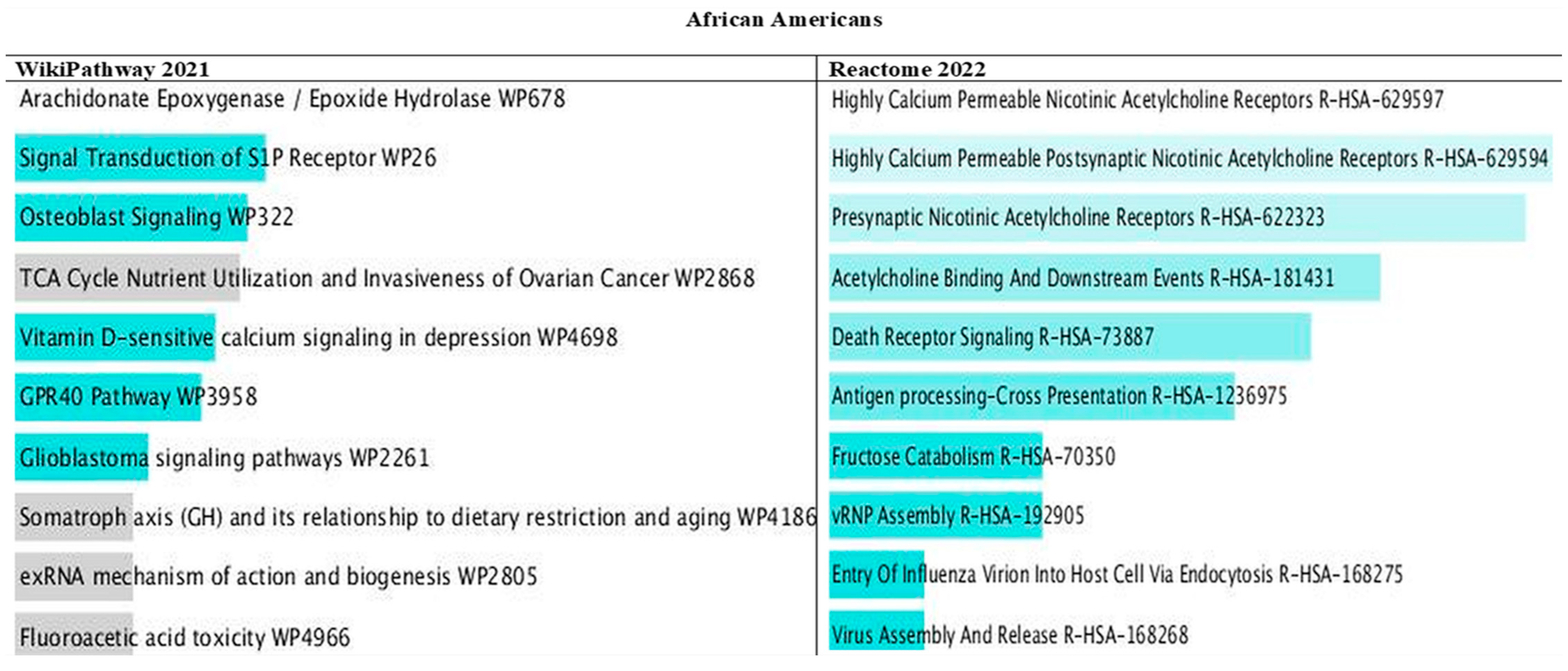

3.10. Pathways of PRS Mapped Genes by Ancestry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

| Datasets | Accession Numbers |

|---|---|

| ARIC | phg000035, phg000079, phs000280 |

| CARDIA | phg000091, phs000285 |

| CHS | phg000183, phs000287 |

| FHS OFFSPRING | phg000004, phs000007 |

| FHS GENX3 | phg000006, phs00007 |

| MESA | phg000071, phs000209 |

| WHI | phg000061, phs000200 |

References

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, e153–e639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M. Metabolic syndrome update. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 26, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, S.; Filion, K.B.; Genest, J.; Joseph, L.; Pilote, L.; Poirier, P.; Rinfret, S.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Eisenberg, M.J. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Choi, S.W.; Mak, T.S.; O’Reilly, P.F. Tutorial: A guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 15, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericson, U.; Hindy, G.; Drake, I.; Schulz, C.-A.; Brunkwall, L.; Hellstrand, S.; Almgren, P.; Orho-Melander, M. Dietary and genetic risk scores and incidence of type 2 diabetes. Genes Nutr. 2018, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, J.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Li, J.; Chung, W.; Hu, Y.; Ma, B.; Li, Y.; Kang, J.H.; Kraft, P.; Liang, L.; et al. Polygenic scores, diet quality, and type 2 diabetes risk: An observational study among 35,759 adults from 3 US cohorts. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, S.R.; Navarro, P.; Harrington, J.M.; Shivappa, N.; Hébert, J.R.; Perry, I.J.; Phillips, C.M. Comparing dietary score associations with lipoprotein particle subclass profiles: A cross-sectional analysis of a middle-to older-aged population. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4720–4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, Y.R.; Robbins, J.M.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djoussé, L. Mediterranean, DASH, and alternate healthy eating index dietary patterns and risk of death in the physicians’ health study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikany, J.M.; Safford, M.M.; Soroka, O.; Brown, T.M.; Newby, P.K.; Durant, R.W.; Judd, S.E. Mediterranean Diet Score, Dietary Patterns, and Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death in the REGARDS Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikany, J.M.; Safford, M.M.; Bryan, J.; Newby, P.K.; Richman, J.S.; Durant, R.W.; Brown, T.M.; Judd, S.E. Dietary Patterns and Mediterranean Diet Score and Hazard of Recurrent Coronary Heart Disease Events and All-Cause Mortality in the REGARDS Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Torres, J.; Alcalá-Diaz, J.F.; Torres-Peña, J.D.; Gutierrez-Mariscal, F.M.; Leon-Acuña, A.; Gómez-Luna, P.; Fernández-Gandara, C.; Quintana-Navarro, G.M.; Fernandez-Garcia, J.C.; Perez-Martinez, P.; et al. Mediterranean Diet Reduces Atherosclerosis Progression in Coronary Heart Disease: An Analysis of the CORDIOPREV Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke 2021, 52, 3440–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikany, J.M.; Safford, M.M.; Newby, P.K.; Durant, R.W.; Brown, T.M.; Judd, S.E. Southern Dietary Pattern is Associated with Hazard of Acute Coronary Heart Disease in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. Circulation 2015, 132, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Physical Inactivity Prevalence Maps by Race/Ethnicity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/index.html#Race-Ethnicity (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; George, S.M.; Olson, R.D. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. The Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes. Updated 2020. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap/ (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- The ARIC investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Design and objectives. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1989, 129, 687–702. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Lewis, C.E.; Schreiner, P.J.; Shikany, J.M.; Sidney, S.; Reis, J.P. The Coronary Artery Risk Development In Young Adults (CARDIA) Study: JACC Focus Seminar 8/8. J. Am Coll Cardiol. 2021, 78, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Borhani, N.O.; Enright, P.; Furberg, C.D.; Gardin, J.M.; Kronmal, R.A.; Kuller, L.H.; Manolio, T.A.; Mittelmark, M.B.; Newman, A.; et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: Design and rationale. Ann. Epidemiol. 1991, 1, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, N.D.; Levy, D. Legacy of the Framingham Heart Study: Rationale, design, initial findings, and implications. Glob. Heart. 2013, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bild, D.E.; Bluemke, D.A.; Burke, G.L.; Detrano, R.; Diez Roux, A.V.; Folsom, A.R.; Greenland, P.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Kronmal, R.; Liu, K.; et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 156, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Women’s Health Initiative Study Group. Design of the Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin. Trials. 1998, 19, 61–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Forer, L.; Schönherr, S.; Sidore, C.; Locke, A.E.; Kwong, A.; Vrieze, S.I.; Chew, E.Y.; Levy, S.; McGue, M.; et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1284–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marees, A.T.; de Kluiver, H.; Stringer, S.; Vorspan, F.; Curis, E.; Marie-Claire, C.; Derks, E.M. A tutorial on conducting genome-wide association studies: Quality control and statistical analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.C.C.; PLINK 1.90 Beta. Updated 2020. Available online: https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Boyle, A.P.; Hong, E.L.; Hariharan, M.; Cheng, Y.; Schaub, M.A.; Kasowski, M.; Karczewski, K.J.; Park, J.; Hitz, B.C.; Weng, S.; et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. Genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA): Methods, data analyses, and interpretations. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1019, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA. 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Mersha, T.B.; Abebe, T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: Its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Hum. Genom. 2015, 9, 1, Erratum in Hum. Genom. 2021, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Sampson, L.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rosner, B.; Bain, C.; Witschi, J.; Hennekens, C.H.; Speizer, F.E. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 122, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). MESA Study of Atherosclerosis Protocol. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mesa-nhlbi.org%2FpublicDocs%2FProtocol%2FMESA_E5_Protocol_01-24-2010.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Framingham Heart Study (FHS). Framingham Heart Study Three Genera-tions of Dedication. Available online: https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-for-researchers/data-available-overview/ (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Women’s Health Initiative Study. Women’s Health Initiative Study Food Frequency Questionnaire. Available online: https://www.whi.org/datasets/diet (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- CARDIA Scientific Resources Section. CARDIA “Restricted” Public Use Data. Available online: https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/study-information/nhlbi-data-repository-data/cardia-documentation (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). Nutrition History. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fchs-nhlbi.org%2Fsites%2Fchs-nhlbi.org%2Ffiles%2Fpage%2FREC25.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Chan, Q.; Stamler, J.; Elliott, P. Dietary Factors and Higher Blood Pressure in African-Americans. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saruarov, Y.; Nuskabayeva, G.; Gencer, M.Z.; Sadykova, K.; Zhunissova, M.; Tatykayeva, U.; Iskandirova, E.; Sarsenova, G.; Durmanova, A.; Gaipov, A.; et al. Associations of Clusters of Cardiovascular Risk Factors with Insulin Resistance and Beta-Cell Functioning in a Working-Age Diabetic-Free Population in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp LLC. Stata Software. Available online: https://www.stata.com/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Tesi, N.; van der Lee, S.; Hulsman, M.; Holstege, H.; Reinders, M.J.T. snpXplorer: A web application to explore human SNP-associations and annotate SNP-sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W603–W612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbani, N.R.; Ligthart, S.; Brown, M.R.; Heath, A.S.; Bebo, A.; Ashley, K.E.; Boerwinkle, E.; Morrison, A.C.; Folsom, A.R.; Aguilar, D.; et al. American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7: Lifestyle Recommendations, Polygenic Risk, and Lifetime Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation 2022, 145, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniansyah, N.; Goodman, M.O.; Kelly, T.N.; Elfassy, T.; Wiggins, K.L.; Bis, J.C.; Guo, X.; Palmas, W.; Taylor, K.D.; Lin, H.J.; et al. A multi-ethnic polygenic risk score is associated with hypertension prevalence and progression throughout adulthood. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, D.S.; Garvin, J.T.; Mersha, T.B. Analysis of ancestry-specific polygenic risk score and diet composition in type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krapohl, E.; Patel, H.; Newhouse, S.; Curtis, C.J.; von Stumm, S.; Dale, P.S.; Zabaneh, D.; Breen, G.; O’Reilly, P.F.; Plomin, R. Multi-polygenic score approach to trait prediction. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinman, R.D.; Fine, E.J. Fructose in perspective. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.; Ezzati, A.; Witt, D.; McLaren, C.; Vial, P. The effects of intermittent fasting regimens in middle-age and older adults: Current state of evidence. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 156, 111617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindikoglu, A.L.; Abdulsada, M.M.; Jain, A.; Jalal, P.K.; Devaraj, S.; Wilhelm, Z.R.; Opekun, A.R.; Jung, S.Y. Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for four consecutive weeks induces anticancer serum proteome response and improves metabolic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widén, E.; Junna, N.; Ruotsalainen, S.; Surakka, I.; Mars, N.; Ripatti, P.; Partanen, J.J.; Aro, J.; Mustonen, P.; Tuomi, T.; et al. How Communicating Polygenic and Clinical Risk for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Impacts Health Behavior: An Observational Follow-up Study. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2022, 15, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, R.; Xu, Z.; Arnold, M.; Ip, S.; Harrison, H.; Barrett, J.; Pennells, L.; Kim, L.G.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Paige, E.; et al. Using Polygenic Risk Scores for Prioritizing Individuals at Greatest Need of a Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2023, 12, e029296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365, l1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochberg, Y.; Benjamini, Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat. Med. 1990, 9, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ancestries Combined | European Americans | African Americans | p Value Comparing African Americans to European Americans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 8181) | (n = 6575) | (n = 1606) | ||

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or Column Percent (%) of Participants | |||

| Age (range:19–98 years; mean: 60 years; SD:10.5) | <0.0001 | |||

| 20–57 years | 46.6 | 44.1 | 57.0 | <0.0001 |

| 58–94 years | 53.4 | 55.9 | 43.0 | |

| Female (%) | 50.8 | 49.5 | 56.3 | <0.0001 |

| Current cigarette smoking (%) | 32.7 | 32.6 | 32.9 | 0.828 |

| Current alcohol intake (%) | 53.3 | 57.3 | 37.2 | <0.0001 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 27.6 (5.1) | 26.9 (4.7) | 29.6 (6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Weight status (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Underweight (BMI ≤ 18.5 kg/m2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 33.0 | 36.4 | 17.1 | |

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 41.7 | 41.3 | 43.4 | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 24.7 | 21.3 | 38.7 | |

| High physical activity level (%) | 51.3 | 51.9 | 48.4 | 0.012 |

| Total caloric intake | 1673.9 (619.2) | 1694.1 (613.7) | 1591.1 (634.8) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference | 96.3 (14.0) | 95.5 (13.6) | 99.3 (15.1) | <0.0001 |

| >102 cm: men and >88 cm: women (%) | 65.7 | 64.4 | 71.0 | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 124.2 (19.9) | 123.0 (19.4) | 129.3 (21.3) | <0.0001 |

| >120 mmHg (%) | 55.1 | 53.1 | 63.4 | <0.0001 |

| HDL cholesterol | 52.7 (16.9) | 52.0 (16.7) | 55.6 (17.4) | <0.0001 |

| <40 mg/dL: men and <50 mg/dL: women (%) | 65.3 | 65.2 | 65.7 | 0.703 |

| Triglycerides | 131.9 (86.7) | 137.3 (89.7) | 109.6 (68.8) | <0.0001 |

| >150 mg/dL (%) | 28.1 | 31.0 | 16.4 | <0.0001 |

| LDL cholesterol | 132.3 (39.3) | 132.6 (38.8) | 131.3 (41.4) | 0.262 |

| >100 mg/dL (%) | 80.7 | 81.0 | 79.5 | 0.158 |

| Fasting blood glucose | 107.2 (34.8) | 105.7 (30.4) | 113.4 (48.3) | <0.0001 |

| >100 mg/dL (%) | 48.6 | 48.2 | 50.6 | 0.076 |

| Blood pressure medications (%) | 36.5 | 33.4 | 49.1 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 17.0 | 18.0 | 13.0 | <0.0001 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 10.4 | 11.6 | 5.6 | <0.0001 |

| Stroke/TIA (%) | 8.1 | 8.6 | 6.1 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 0.001 |

| Polygenic risk score | 0.048 (0.953) | 0.064 (0.953) | −0.016 (0.999) | 0.003 |

| Risk Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Americans | p Value | African Americans | p Value | |

| (n = 6575) | (n = 1606) | |||

| Polygenic risk score | ||||

| PRS per 1 SD Z score | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | 0.003 * | 1.23 (1.08–1.40) | 0.001 * |

| PRS lowest tertile | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| PRS second tertile | 1.15 (1.13–1.30) | 0.031 | 1.33 (0.96–1.46) | 0.085 |

| PRS highest tertile | 1.18 (1.04–1.35) | 0.009 * | 1.59 (1.16–2.17) | 0.005 * |

| Dietary Patterns | ||||

| DASH diet per 1 SD Z score | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) | 0.002 * | 0.83 (0.73–0.94) | 0.004 * |

| Lowest tertile | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| Second tertile | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 0.320 | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | 0.141 |

| Highest tertile | 0.85 (0.75–0.95) | 0.006 * | 0.64 (0.47–0.89) | 0.008 * |

| Mediterranean diet per 1 SD Z score | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | <0.0001 * | 0.87 (0.77–0.99) | 0.033 |

| Lowest tertile | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| second tertile | 0.85 (0.76–0.96) | 0.011 * | 1.13 (0.65–1.97) | 0.668 |

| highest tertile | 0.83 (0.72–0.95) | 0.008 * | 0.71 (0.52–0.97) | 0.029 |

| Southern diet per 1 SD Z score | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.004 * | 1.25 (1.08–1.44) | 0.002 * |

| Lowest tertile | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| second tertile | 1.18 (1.04–1.33) | 0.009 * | 1.31 (0.91–1.87) | 0.142 |

| highest tertile | 1.19 (1.05–1.34) | 0.008 * | 1.76 (1.21–2.56) | 0.003 * |

| Physical activity | ||||

| Physical activity (high vs. low) | 0.71 (0.63–0.79) | <0.0001 * | 0.53 (0.40–0.69) | <0.0001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hardy, D.S.; Garvin, J.T.; Mersha, T.B. Ancestry Specific Polygenic Risk Score, Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040567

Hardy DS, Garvin JT, Mersha TB. Ancestry Specific Polygenic Risk Score, Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients. 2024; 16(4):567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040567

Chicago/Turabian StyleHardy, Dale S., Jane T. Garvin, and Tesfaye B. Mersha. 2024. "Ancestry Specific Polygenic Risk Score, Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease" Nutrients 16, no. 4: 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040567

APA StyleHardy, D. S., Garvin, J. T., & Mersha, T. B. (2024). Ancestry Specific Polygenic Risk Score, Dietary Patterns, Physical Activity, and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients, 16(4), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040567