Associations between Shokuiku during School Years, Well-Balanced Diets, and Eating and Lifestyle Behaviours in Japanese Females Enrolled in a University Registered Dietitian Course

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

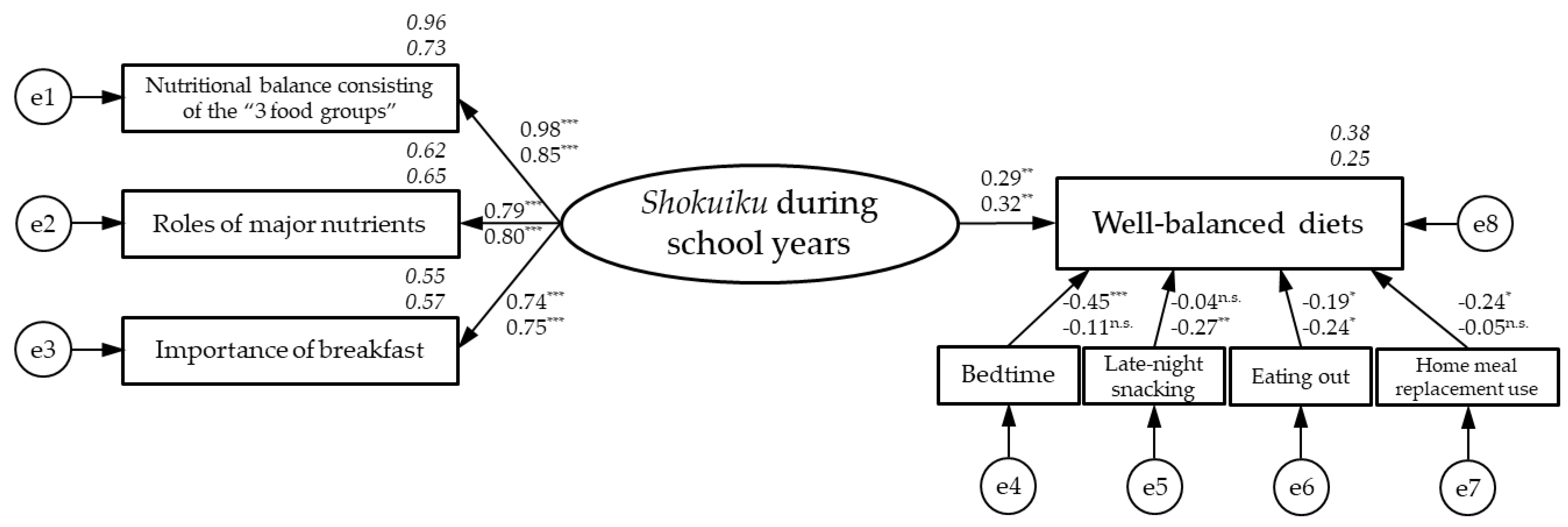

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- US Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2010. Available online: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2020-01/DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf?utm_source=blog&utm_campaign=rc_blogpost (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—United States of America. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/united-states-of-america/previous-versions-2010/en/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- US Department of Health and Human Services; US Department of Agriculture: 2015–2020. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Available online: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2024).

- Schwingshackl, L.; Bogensberger, B.; Hoffmann, G. Diet Quality as Assessed by the Healthy Eating Index, Alternate Healthy Eating Index, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Score, and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 74–100.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—Japan. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/japan/en/ (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Oba, S.; Nagata, C.; Nakamura, K.; Fujii, K.; Kawachi, T.; Takatsuka, N.; Shimizu, H. Diet Based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top and Subsequent Mortality Among Men and Women in a General Japanese Population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurotani, K.; Akter, S.; Kashino, I.; Goto, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center based Prospective Study Group. Quality of Diet and Mortality Among Japanese Men and Women: Japan Public Health Center Based Prospective Study. BMJ 2016, 352, i1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiike, N.; Hayashi, F.; Takemi, Y.; Mizoguchi, K.; Seino, F. A New Food Guide in Japan: The Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The Fourth Basic Program for Shokuiku Promotion (Provisional Translation). Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/attach/pdf/kannrennhou-30.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Japan Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2018. Available online: https://www.niph.go.jp/h-crisis/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/20200115104433_content_10900000_000584138.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2023). (In Japanese)

- Nakade, M.; Kibayashi, E.; Morooka, A. The Relationship Between Eating Behavior and a Japanese Well-Balanced Diet Among Young Adults Aged 20–39 Years. J. Jpn. Soc. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 74, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2015. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/dl/h27-houkoku.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2023). (In Japanese).

- NPD Japan Ltd. Domestic Restaurants and Ready-to-Eat Outlets Survey Report. Available online: https://www.npdjapan.com/cms/data/2022/07/abb1fd5c709dcb5a5ebd1ec2c30e1054-1.pdf (accessed on 25 December 2023). (In Japanese).

- Overcash, F.; Reicks, M. Diet Quality and Eating Practices Among Hispanic/Latino Men and Women: NHANES 2011–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, E.; Kim, M.; Kim, W.G.; Yoon, J. Nutritional Aspects of Night Eating and Its Association with Weight Status Among Korean Adolescents. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016, 10, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraccio, K.M.; Whitacre, C.; Krietsch, K.N.; Zhang, N.; Summer, S.; Price, M.; Saelens, B.E.; Beebe, D.W. Losing Sleep by Staying up Late Leads Adolescents to Consume More Carbohydrates and a Higher Glycemic Load. Sleep 2022, 45, zsab269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, K.L.; Collins, P.F. Relationship Between Living Alone and Food and Nutrient Intake. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Attitude Survey about Shokuiku. 2017. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/ishiki//h29pdf.html (accessed on 26 January 2024). (In Japanese)

- Honda, A.; Nakashita, C.; Ikegami, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Yoshimura, E.; Shimoda, S.; Matsuzoe, N.; Matsusaki, H. A survey on changes over time in eating habits and food attitudes among university students: 3 years longitudinal survey. J. Jpn. Soc. Shokuiku 2021, 15, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H. Covariance Structure Analysis (Amos Edition)—Structural Equation Modeling; Tokyo Tosho Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power Analysis and Determination of Sample Size for Covariance Structure Modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibayashi, E. Association of Self-Esteem with Dietary and Lifestyle Habit Self-Efficacy, Stage of Eating Behavior Change, and Dietary Intake in High School Students. Eiyougakuzashi. 2022, 80, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.W.; Kreuter, K.W. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach, 4th ed.; Jinma, M., Ed.; Igaku-Shoin, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J.N.; Haslam, R.L.; Clarke, E.; Attia, J.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Callister, R.; Burrows, T.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A.; et al. Eating Behaviors and Diet Quality: A National Survey of Australian Young Adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C.; Bentley, R.; Thornton, L.; Kavanagh, A. Reduced Food Access Due to a Lack of Money, Inability to Lift and Lack of Access to a Car for Food Shopping: A Multilevel Study in Melbourne, Victoria. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, A.; Frazao, E. Are Healthy Foods Really More Expensive? It Depends on How You Measure the Price, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, EIB-96. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44678/19980_eib96.pdf?v=7067.9 (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Ricken, J.; Havel, M.; Guth, A.; Merrow, M. A Marker for the End of Adolescence. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R1038–R1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randler, C. Age and Gender Differences in Morningness-Eveningness During Adolescence. J. Genet. Psychol. 2011, 172, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiura, C.; Noguchi, J.; Hashimoto, H. Dietary Patterns Only Partially Explain the Effect of Short Sleep Duration on the Incidence of Obesity. Sleep 2010, 33, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total | Living Alone | Living with Family | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 148 | n = 72 | n = 76 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age † | |||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 0.27 | ||||

| (19, 21) | (19, 21) | (19, 21) | |||||

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) ‡ | |||||||

| <18.5 | 26 | 17.6 | 9 | 12.5 | 17 | 22.4 | 0.12 |

| ≥18.5 and <25 | 122 | 82.4 | 63 | 87.5 | 59 | 77.6 | |

| ≥25 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Financial well-being ‡ | |||||||

| Stable | 25 | 16.9 | 11 | 15.3 | 14 | 18.4 | 0.84 |

| Somewhat stable | 72 | 48.6 | 35 | 48.6 | 37 | 48.7 | |

| Cannot say either | 30 | 20.3 | 16 | 22.2 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| Not very stable | 20 | 13.5 | 10 | 13.9 | 10 | 13.2 | |

| Not at all stable | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Regular exercise ‡ | |||||||

| At least 2 days/week of exercise for at least 30 min continuously over 1 year | |||||||

| Yes | 20 | 13.5 | 11 | 15.3 | 9 | 11.8 | 0.54 |

| No | 128 | 86.5 | 61 | 84.7 | 67 | 88.2 | |

| Cooking for oneself § | |||||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 28 | 18.9 | 26 | 36.1 | 2 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 25 | 16.9 | 21 | 29.2 | 4 | 5.3 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 35 | 23.6 | 18 | 25.0 | 17 | 22.4 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 60 | 40.5 | 7 | 9.7 | 53 | 69.7 | |

| Eating meals with family or friends § | |||||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 52 | 35.1 | 2 | 2.8 | 50 | 65.8 | <0.001 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 24 | 16.2 | 7 | 9.7 | 17 | 22.4 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 35 | 23.6 | 27 | 37.5 | 8 | 10.5 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 37 | 25.0 | 36 | 50.0 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Regular breakfast consumption § | |||||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 92 | 62.2 | 34 | 47.2 | 58 | 76.3 | <0.001 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 27 | 18.2 | 18 | 25.0 | 9 | 11.8 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 20 | 13.5 | 12 | 16.7 | 8 | 10.5 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 9 | 6.1 | 8 | 11.1 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Well-balanced diets § | |||||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 29 | 19.6 | 9 | 12.5 | 20 | 26.3 | <0.001 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 33 | 22.3 | 12 | 16.7 | 21 | 27.6 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 39 | 26.4 | 18 | 25.0 | 21 | 27.6 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 47 | 31.8 | 33 | 45.8 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| Living Alone | Living with Family | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 72 | n = 76 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Shokuiku during school years, i.e., past conversations about the following three items: | |||||

| 1. Nutritional balance consisting of the “three food groups” | |||||

| Agree | 22 | 30.6 | 17 | 22.4 | 0.58 |

| Somewhat agree | 14 | 19.4 | 22 | 28.9 | |

| Cannot say either | 17 | 23.6 | 10 | 13.2 | |

| Not very agree | 13 | 18.1 | 24 | 31.6 | |

| Not at all agree | 6 | 8.3 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| 2. Role of major nutrients | |||||

| Agree | 15 | 20.8 | 13 | 17.1 | 0.93 |

| Somewhat agree | 22 | 30.6 | 28 | 36.8 | |

| Cannot say either | 12 | 16.7 | 11 | 14.5 | |

| Not very agree | 18 | 25.0 | 18 | 23.7 | |

| Not at all agree | 5 | 6.9 | 6 | 7.9 | |

| 3. Importance of breakfast | |||||

| Agree | 32 | 44.4 | 20 | 26.3 | 0.24 |

| Somewhat agree | 14 | 19.4 | 29 | 38.2 | |

| Cannot say either | 13 | 18.1 | 8 | 10.5 | |

| Not very agree | 9 | 12.5 | 15 | 19.7 | |

| Not at all agree | 4 | 5.6 | 4 | 5.3 | |

| Current eating and lifestyle behaviours as limiting factors | |||||

| Bedtime | |||||

| After 2:00 a.m. | 32 | 44.4 | 17 | 22.4 | 0.001 |

| From 1:00 a.m. to 2:00 a.m. | 27 | 37.5 | 29 | 38.2 | |

| From 0:00 a.m. to 1:00 a.m. | 10 | 13.9 | 20 | 26.3 | |

| Before 0:00 a.m. | 3 | 4.2 | 10 | 13.2 | |

| Snacking frequency (except for late-night snacking) | |||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 13 | 18.1 | 24 | 31.6 | 0.10 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 20 | 27.8 | 17 | 22.4 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 29 | 40.3 | 28 | 36.8 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 10 | 13.9 | 7 | 9.2 | |

| Late-night snacking frequency (from after dinner until bedtime) | |||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 2 | 2.8 | 4 | 5.3 | 0.67 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 4 | 5.6 | 6 | 7.9 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 18 | 25.0 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 48 | 66.7 | 52 | 68.4 | |

| Eating-out frequency | |||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.053 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 2 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 20 | 27.8 | 14 | 18.4 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 50 | 69.4 | 62 | 81.6 | |

| Home meal replacement (ready-to-eat foods) use frequency | |||||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.6 | 0.91 |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 4 | 5.6 | 6 | 7.9 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 25 | 34.7 | 19 | 25.0 | |

| 1 day/week or less | 42 | 58.3 | 49 | 64.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M. Associations between Shokuiku during School Years, Well-Balanced Diets, and Eating and Lifestyle Behaviours in Japanese Females Enrolled in a University Registered Dietitian Course. Nutrients 2024, 16, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040484

Kibayashi E, Nakade M. Associations between Shokuiku during School Years, Well-Balanced Diets, and Eating and Lifestyle Behaviours in Japanese Females Enrolled in a University Registered Dietitian Course. Nutrients. 2024; 16(4):484. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040484

Chicago/Turabian StyleKibayashi, Etsuko, and Makiko Nakade. 2024. "Associations between Shokuiku during School Years, Well-Balanced Diets, and Eating and Lifestyle Behaviours in Japanese Females Enrolled in a University Registered Dietitian Course" Nutrients 16, no. 4: 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040484

APA StyleKibayashi, E., & Nakade, M. (2024). Associations between Shokuiku during School Years, Well-Balanced Diets, and Eating and Lifestyle Behaviours in Japanese Females Enrolled in a University Registered Dietitian Course. Nutrients, 16(4), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040484