Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with the Incidence of Cardiometabolic and Mental Health Outcomes Go Beyond Specific Subgroups—The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health

Highlights

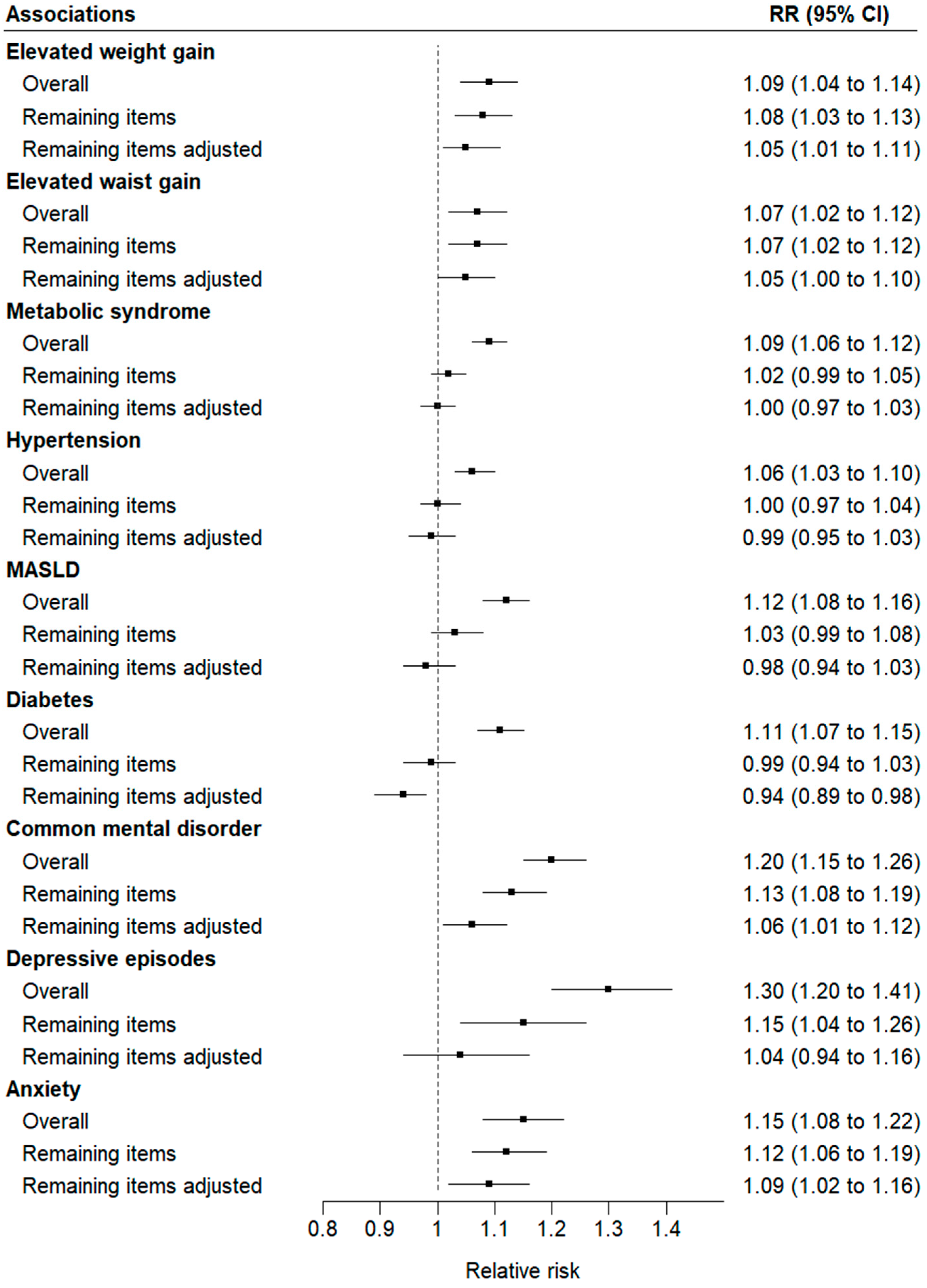

- A greater overall intake of ultra-processed foods (UPFs) at baseline predicted the risk of developing nine cardiometabolic and mental health disorders.

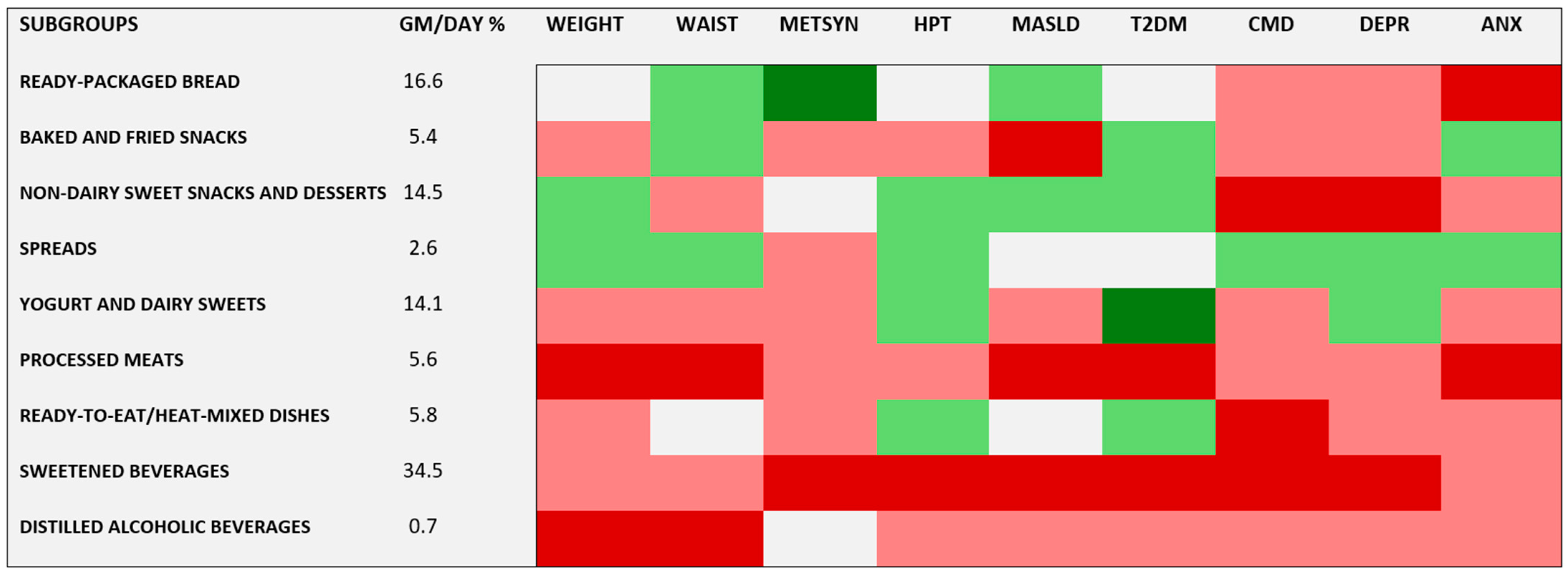

- When analyzing the UPF subgroups, most of them predicted risk of at least one of and usually more than one of the outcomes, with processed meats and sweetened beverages being particularly prominent.

- A higher consumption of an aggregate of UPF subgroups that did not individually predict risk conferred a greater risk of many of the evaluated conditions, including overall and central adiposity—key drivers of today’s disease burden.

- The health benefits of avoiding UPFs extend beyond reducing the consumption of specific UPF subgroups, underscoring the importance of addressing the overall concept of UPFs in public health messaging and clinical dietary interventions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

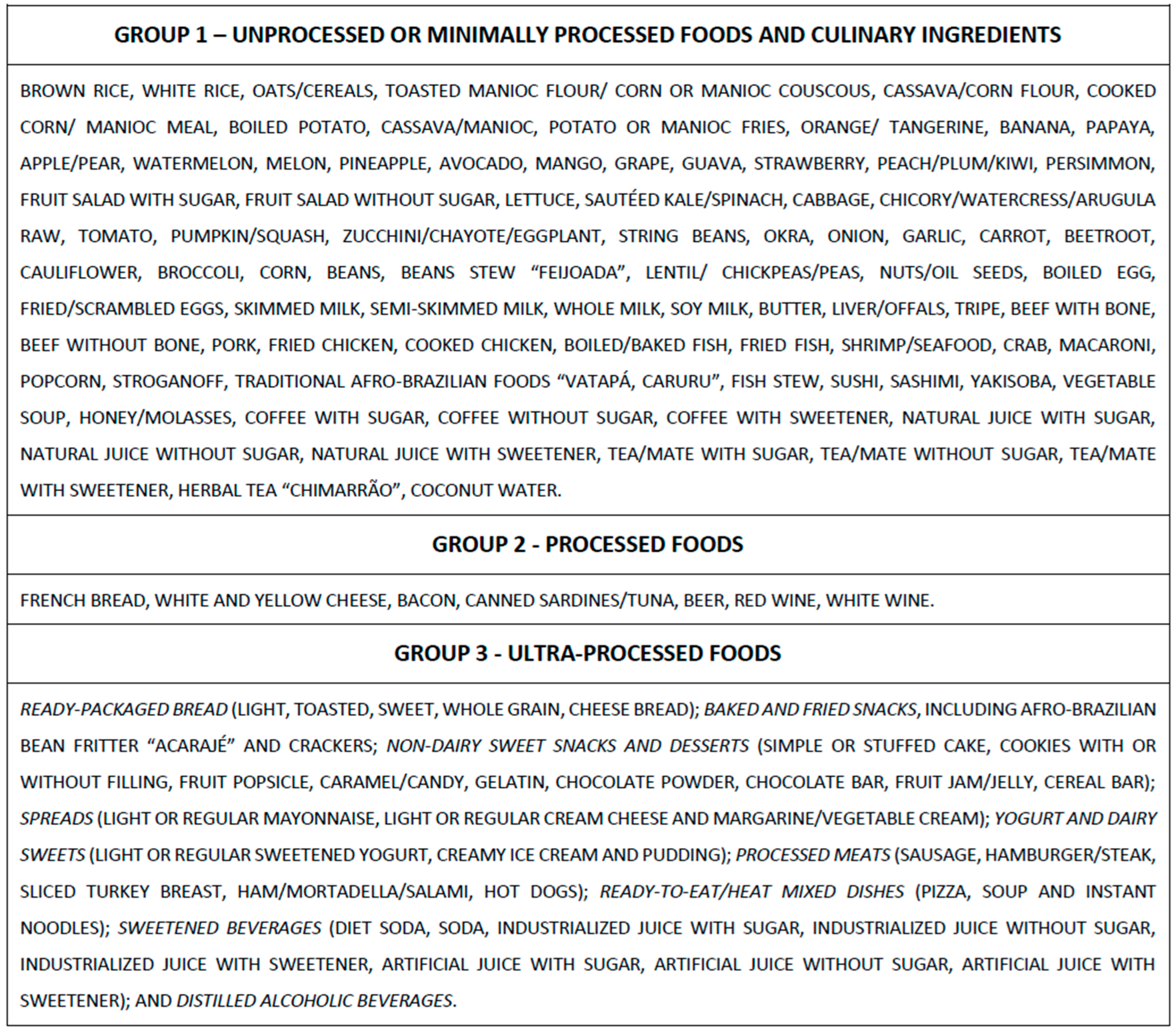

2.2. Definition of Ultra-Processed Foods

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Cannon, G.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Ultra-Processed Products Are Becoming Dominant in the Global Food System. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-Processed Foods: What They Are and How to Identify Them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde; Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde; Departamento de Atenção Básica. Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014.

- Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Vadiveloo, M.; Hu, F.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Sacks, F.M.; Thorndike, A.N.; Van Horn, L.; Wylie-Rosett, J. 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, E472–E487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, T.H.; Sheron, N.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Carrieri, P.; Dusheiko, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Pryke, R.; Hutchinson, S.J.; Sangro, B.; Martin, N.K.; et al. The EASL–Lancet Liver Commission: Protecting the next Generation of Europeans against Liver Disease Complications and Premature Mortality. Lancet 2022, 399, 61–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud; Instituto Nacional de Salud. Guías Alimentarias Para La Población Peruana; Ministerio de Salud: Lima, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—France. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/france/en/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública Guía Alimentaria Para La Población Uruguaya. Available online: https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-salud-publica/comunicacion/publicaciones/guia-alimentaria-para-poblacion-uruguaya (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Ministerio de Salud. Guías Alimentarias Para Chile; Ministerio de Salud: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; Mcguinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Exposure and Adverse Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Epidemiological Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Khandpur, N.; Desjardins, C.; Wang, L.; Monteiro, C.A.; Rossato, S.L.; Fung, T.T.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canhada, S.L.; Vigo, Á.; Levy, R.; Luft, V.C.; da Fonseca, M.D.; Giatti, L.; Molina, M.D.; Duncan, B.B.; Schmidt, M.I. Association between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes: The ELSA-Brasil Cohort. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Sullivan, V.K.; Fang, M.; Appel, L.J.; Selvin, E.; Rebholz, C.M. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Diabetes: Results from a Population-Based Prospective Cohort. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Ryu, S.; Kim, R.; Shin, M.J.; Oh, H. Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Korean Adults. J. Nutr. 2024, 154, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadiveloo, M.K.; Gardner, C.D. Not All Ultra-Processed Foods Are Created Equal: A Case for Advancing Research and Policy that Balances Health and Nutrition Security. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1327–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, E.M.L.; Barreto, S.M.; Bensenor, I.M.; Carvalho, M.S.; Chor, D.; Duncan, B.B.; Lotufo, P.A.; Mill, J.G.; Molina, M.D.C.; Mota, E.L.A.; et al. Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil): Objectives and Design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.I.; Duncan, B.B.; Mill, J.G.; Lotufo, P.A.; Chor, D.; Barreto, S.M.; Aquino, E.M.L.; Passos, V.M.A.; Matos, S.M.A.; Molina, M.D.; et al. Cohort Profile: Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, M.D.C.B.; Benseñor, I.M.; Cardoso, L.D.; Velasquez-Melendez, G.; Drehmer, M.; Pereira, T.S.; Faria, C.P.; Melere, C.; Manato, L.; Gomes, A.L.; et al. Reproducibility and Relative Validity of the Food Frequency Questionnaire Used in the ELSA-Brasil. Cad. Saude Publica 2013, 29, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.T.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome: A Joint Interim Statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D. A Multi-Society Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedogni, G.; Bellentani, S.; Miglioli, L.; Masutti, F.; Passalacqua, M.; Castiglione, A.; Tiribelli, C. The Fatty Liver Index: A Simple and Accurate Predictor of Hepatic Steatosis in the General Population. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycaemia. WHO 2006, 1, 161–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.; Pelosi, A.J.; Araya, R.; Dunn, G. Measuring Psychiatric Disorder in the Community: A Standardized Assessment for Use by Lay Interviewers. Psychol. Med. 1992, 22, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, T.T.; Rossato, S.L.; Chen, Z.; Khandpur, N.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Willett, W.C.; Struijk, E.A.; Lopez-Garcia, E. Ultraprocessed Foods, Unprocessed or Minimally Processed Foods, and Risk of Frailty in a Cohort of United States Females. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 120, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 25. Vellinga, R.E.; van den Boomgaard, I.; Boer, J.M.A.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Harbers, M.C.; Verschuren, W.M.M.; van’t Veer, P.; Temme, E.H.M.; Biesbroek, S. Different Levels of Ultraprocessed Food and Beverage Consumption and Associations with Environmental Sustainability and All-Cause Mortality in EPIC-NL. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaesser, G.A. Refined Grain Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srour, B.; Kordahi, M.C.; Bonazzi, E.; Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Touvier, M.; Chassaing, B. Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health: From Epidemiological Evidence to Mechanistic Insights. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 1128–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Godos, J.; Bonaccio, M.; Vitaglione, P.; Grosso, G. Ultra-Processed Foods and Nutritional Dietary Profile: A Meta-Analysis of Nationally Representative Samples. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.T.; Lin, C.H.; Pai, H.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Cheng, K.P.; Kuo, H.Y.; Li, C.H.; Ou, H.Y. Sucralose, a Non-Nutritive Artificial Sweetener Exacerbates High Fat Diet-Induced Hepatic Steatosis Through Taste Receptor Type 1 Member 3. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 823723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellem, L.; Srour, B.; Javaux, G.; Chazelas, E.; Chassaing, B.; Viennois, E.; Debras, C.; Salamé, C.; Druesne-pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; et al. Food Additive Emulsifiers and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the NutriNet-Santé Cohort: Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2023, 382, e076058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk-Baker, M.K.; Nagy, T.R.; Barnes, S.; Groopman, J. Dietary Acrylamide and Human Cancer: A Systematic Review of Literature. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 66, 774–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanoska, M.M.; Milosevic, N.; Milic, N.; Abenavoli, L. The Influence of Phthalates and Bisphenol A on the Obesity Development and Glucose Metabolism Disorders. Endocrine 2017, 55, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suez, J.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Zilberman-Schapira, G.; Thaiss, C.A.; Maza, O.; Israeli, D.; Zmora, N.; Gilad, S.; Weinberger, A.; et al. Artificial Sweeteners Induce Glucose Intolerance by Altering the Gut Microbiota. Nature 2014, 514, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vos, W.M.; Tilg, H.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut Microbiome and Health: Mechanistic Insights. Gut 2022, 71, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A. Minimally Processed Foods Are More Satiating and Less Hyperglycemic than Ultra-Processed Foods: A Preliminary Study with 98 Ready-to-Eat Foods. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearhardt, A. Social, Clinical, and Policy Implications of Ultra- Processed Food Addiction. BMJ 2023, 383, e075354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBGE. Pesquisa de Orçamentos Familiares 2017–2018: Análise de Consumo Alimentar Pessoal No Brasil; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; ISBN 9788524041389.

- Anastasiou, K.; Baker, P.; Hadjikakou, M.; Hendrie, G.A.; Lawrence, M. A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Environmental Impacts of Ultra-Processed Foods and Implications for Sustainable Food Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Jaime, P.C. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA Food Classification and the Trouble with Ultra-Processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total (n = 13,651) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | N | % | Median | IQR | |

| Age (years) | 52.0 | 9.0 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 7528 | 55.2 | ||||

| Race/skin color | ||||||

| Black | 2172 | 15.9 | ||||

| Brown | 3801 | 27.8 | ||||

| White | 7191 | 52.7 | ||||

| Asian | 343 | 2.5 | ||||

| Indigenous | 144 | 1.1 | ||||

| Income (reais) | 1411 | 726–2282 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than elementary | 732 | 5.3 | ||||

| Elementary | 887 | 6.5 | ||||

| Secondary | 4691 | 34.4 | ||||

| College/university | 7341 | 53.8 | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 7888 | 57.8 | ||||

| Former smoker | 4076 | 29.9 | ||||

| Current smoker | 1687 | 12.3 | ||||

| Physical activity (MET-minutes/week) | 240 | 0–960 | ||||

| Alcohol consumption (g/d) | 0 | 0–67.2 | ||||

| Energy intake (kcal/d) | 2613 | 932 | ||||

| UPF (g/d) | 436 | 293 | ||||

| UPF subgroups (g/d) | ||||||

| Ready-packaged bread | 56.2 | 48.0 | ||||

| Baked and fried snacks | 19.0 | 21.0 | ||||

| Non-dairy sweet snacks and desserts | 57.4 | 57.0 | ||||

| Spreads | 9.3 | 11.6 | ||||

| Yogurt and dairy sweets | 56.5 | 61.9 | ||||

| Processed meats | 20.9 | 21.6 | ||||

| Ready-to-eat/heat-mixed dishes | 21.8 | 25.2 | ||||

| Sweetened beverages | 192 | 231 | ||||

| Distilled alcoholic beverages | 2.3 | 8.4 | ||||

| Total | Incident | Follow-Up | Difference in One-Standard Deviation ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Cases | Time * | Crude | Adjusted *** | ||

| Outcomes | N | N | % | Years | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

| Elevated weight gain | 13,316 | 1333 | 10.0 | 7.8 (1.3) | 1.17 (1.12–1.22) | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) |

| Elevated waist gain | 13,297 | 1376 | 10.4 | 7.8 (1.4) | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 8115 | 2541 | 31.3 | 7.9 (1.3) | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) |

| Hypertension | 8744 | 2013 | 23.0 | 7.9 (1.3) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) |

| MASLD | 8699 | 1893 | 21.8 | 7.9 (1.3) | 1.17 (1.13–1.20) | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) |

| Diabetes | 11,405 | 1884 | 16.5 | 7.8 (1.3) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | 1.11 (1.07–1.15) |

| Common mental disorders | 8745 | 1128 | 12.9 | 8.2 (0.5) | 1.20 (1.15–1.25) | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) |

| Depressive episodes | 12,753 | 393 | 3.1 | 7.8 (1.3) | 1.28 (1.19–1.39) | 1.30 (1.20–1.41) |

| Anxiety disorders | 9971 | 789 | 7.9 | 8.2 (0.5) | 1.15 (1.08–1.21) | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) |

| Crude | Adjusted ** | |

|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | RR (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) |

| Elevated weight gain | ||

| Processed meats | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 1.07 (1.02–1 13) |

| Distilled alcoholic beverages | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) |

| Elevated waist gain | ||

| Processed meats | 1.08 (1.03–1.14) | 1.07 (1.02–1.13) |

| Distilled alcoholic beverages | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 1.14 (1.08–1.20) |

| Metabolic syndrome | ||

| Sweetened beverages | 1.10 (1.07–1.14) | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) |

| Hypertension | ||

| Sweetened beverages | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) |

| MASLD | ||

| Baked and fried snacks | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) |

| Processed meats | 1.13 (1.09–1.17) | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) |

| Sweetened beverages | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 1.09 (1.05–1.12) |

| Diabetes | ||

| Processed meats | 1.05 (1.00–1.09) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) |

| Sweetened beverages | 1.14 (1.09–1.18) | 1.14 (1.09–1.18) |

| Common mental disorders | ||

| Non-dairy sweet snacks/desserts | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 1.08 (1.02–1.13) |

| Ready-to-eat/heat-mixed dishes | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 1.07 (1.01–1.12) |

| Sweetened beverages | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) | 1.10 (1.05–1.16) |

| Depressive episodes | ||

| Non-dairy sweet snacks/desserts | 1.17 (1.08–1.28) | 1.13 (1.03–1.22) |

| Sweetened beverages | 1.23 (1.13–1.33) | 1.23 (1.13–1.34) |

| Anxiety disorders | ||

| Ready-packaged bread | 1.07 (1.00–1.15) | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) |

| Processed meats | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canhada, S.L.; Vigo, Á.; Giatti, L.; Fonseca, M.d.J.; Lopes, L.J.; Cardoso, L.d.O.; Monteiro, C.A.; Schmidt, M.I.; Duncan, B.B. Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with the Incidence of Cardiometabolic and Mental Health Outcomes Go Beyond Specific Subgroups—The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244291

Canhada SL, Vigo Á, Giatti L, Fonseca MdJ, Lopes LJ, Cardoso LdO, Monteiro CA, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB. Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with the Incidence of Cardiometabolic and Mental Health Outcomes Go Beyond Specific Subgroups—The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health. Nutrients. 2024; 16(24):4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244291

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanhada, Scheine Leite, Álvaro Vigo, Luana Giatti, Maria de Jesus Fonseca, Leidjaira Juvanhol Lopes, Letícia de Oliveira Cardoso, Carlos Augusto Monteiro, Maria Inês Schmidt, and Bruce Bartholow Duncan. 2024. "Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with the Incidence of Cardiometabolic and Mental Health Outcomes Go Beyond Specific Subgroups—The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health" Nutrients 16, no. 24: 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244291

APA StyleCanhada, S. L., Vigo, Á., Giatti, L., Fonseca, M. d. J., Lopes, L. J., Cardoso, L. d. O., Monteiro, C. A., Schmidt, M. I., & Duncan, B. B. (2024). Associations of Ultra-Processed Food Intake with the Incidence of Cardiometabolic and Mental Health Outcomes Go Beyond Specific Subgroups—The Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health. Nutrients, 16(24), 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16244291