Associations Between Body Appreciation, Body Weight, Lifestyle Factors and Subjective Health Among Bachelor Students in Lithuania and Poland: Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

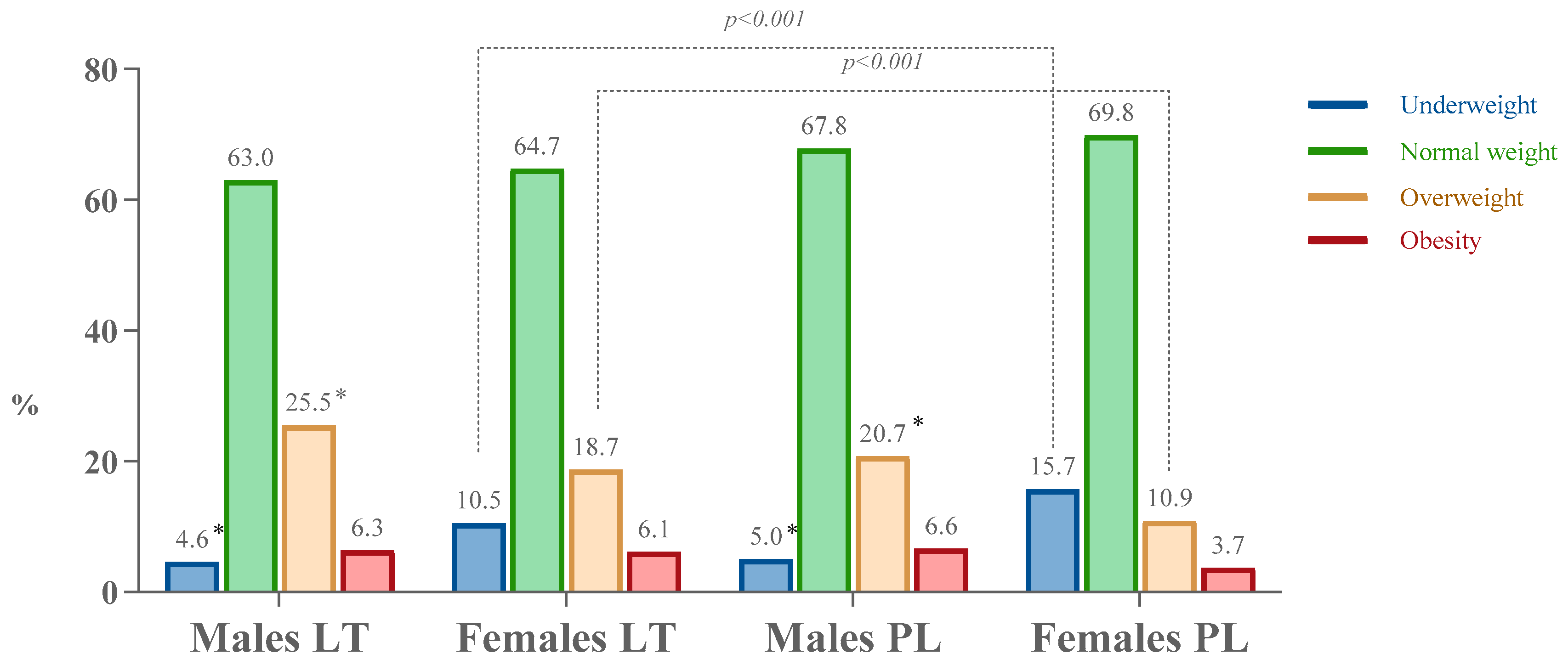

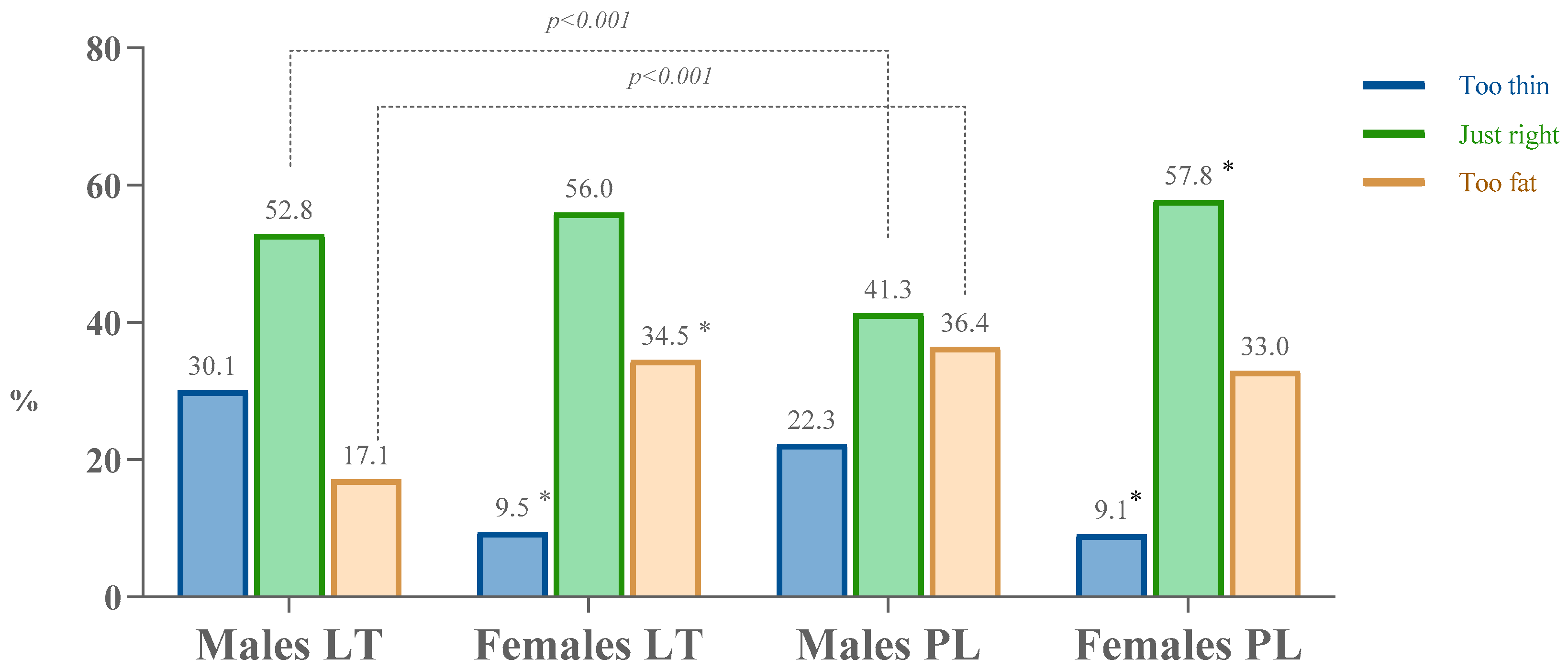

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. The Body Appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2015, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baceviciene, M.; Jankauskiene, R. Associations between body appreciation and disordered eating in a large sample of adolescents. J. Nutr. 2020, 12, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoraie, N.M.; Alothmani, N.M.; Alomari, W.D.; Al-Amoudi, A.H. Addressing Nutritional Issues and Eating Behaviors Among University Students: A Narrative Review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avalos, L.; Tylka, T.L.; Wood-Barcalow, N.L. The body appreciation scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2005, 2, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Alwafa, R.; Badrasawi, M. Factors associated with positive body image among Palestinian university female students, cross-sectional study. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2023, 11, 2278289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V.; Tran, U.S.; Stieger, S.; Aavik, T.; Ranjbar, H.A.; Adebayo, S.O.; Afhami, R.; Ahmed, O.; Aimé, A.; Akel, M.; et al. Body appreciation around the world: Measurement invariance of the Body Appreciation Scale-2 (BAS-2) across 65 nations, 40 languages, gender identities, and age. Body Image 2023, 46, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, W.; Yang, H. Self-appreciation is not enough: Exercise identity mediates body appreciation and physical activity and the role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1377772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quittkat, H.L.; Hartmann, A.S.; Düsing, R.; Buhlmann, U.; Vocks, S. Body Dissatisfaction, Importance of Appearance, and Body Appreciation in Men and Women over the Lifespan. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Ng, S.K. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Body Appreciation Scale-2 in university students in Hong Kong. Body Image 2015, 15, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Larson, N.I.; Christoph, J.M.; Sherwood, N.E. Eating, activity, and weight-related problems from adolescence to adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, A.; Myszkowska-Ryciak, J.; Harton, A.; Lange, E.; Laskowski, W.; Hamulka, J.; Gajewska, D. Dissatisfaction with Body Weight among Polish Adolescents Is Related to Unhealthy Dietary Behaviors. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, L.S.; Cipriani, M.; Coelho, F.D.; Paes, T.P.; Ferreira, M.E.C. Does self-esteem affect body dissatisfaction levels in female adolescents? A autoestima afeta a insatisfação corporal em adolescentes do sexo feminino? Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2014, 32, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriaucioniene, V.; Raskiliene, A.; Petrauskas, D.; Petkeviciene, J. Trends in Eating Habits and Body Weight Status, Perception Patterns and Management Practices among First-Year Students of Kaunas (Lithuania) Universities, 2000–2017. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszka, W.; Owczarek, A.J.; Glinianowicz, M.; Bąk-Sosnowska, M.; Chudek, J.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Perception of body size and body dissatisfaction in adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincente-Benito, I.; Ramírez-Durán, M.D.V. Influence of Social Media Use on Body Image and Well-Being Among Adolescents and Young Adults A Systematic Review. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2023, 61, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, J.S.; Musto, S.; Williams, L.; Tiggemann, M. “Selfie” Harm: Effects on Mood and Body Image in Young Women. Body Image 2018, 27, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.; Azevedo, Â.S. Implications of Socio-Cultural Pressure for a Thin Body Image on Avoidance of Social Interaction and on Corrective, Compensatory or Compulsive Shopping Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Ansari, W.E.; Maxwell, A.E. Food consumption frequency and perceived stress and depressive symptoms among students in three European countries. Nutr. J. 2009, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report on a WHO Consultation; Report No. 894; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Nieto-Ventura, A. Eating Behavior and Relationships with Stress, Anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia in University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Soo, Z.M.; Patterson, A.J.; Hutchesson, M.J. University Students Purchasing Food on Campus More Frequently Consume More Energy-Dense, Nutrient-Poor Foods: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, N.; Aslan Ceylan, J.; Hatipoğlu, A. The relationship of fast-food consumption with sociodemographic factors, body mass index and dietary habits among university students. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 53, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alafif, N.; Alruwaili, N.W. Sleep duration, body mass index, and dietary behaviour among KSU students. Nutrients 2023, 15, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliga, E.; Cieśla, E.; Michel, S.; Kaducakova, H.; Martin, T.; Śliwiński, G.; Braun, A.; Izova, M.; Lehotska, M.; Kozieł, D.; et al. Diet Quality Compared to the Nutritional Knowledge of Polish, German, and Slovakian University Students—Preliminary Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platta, A.M.; Mikulec, A.T.; Radzymińska, M.; Ruszkowska, M.; Suwała, G.; Zborowski, M.; Kowalczewski, P.L.; Nowicki, M. Body image and willingness to change it—A study of university students in Poland. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, M.; Rudy, M.; Stanisławczyk, M. Gender Differences in Dietary Habits and Nutrition Knowledge Among Polish University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.S.; Tarnowska, A. Eating habits of Polish university students depending on the direction of studies and gender. Brit. Food J. 2019, 121, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryar, C.D.; Hughes, J.P.; Herrick, K.A. Fast Food Consumption Among Adults in the United States, 2013–2016; NCHS Data Briefs No. 322. 2018. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/59582?utm_source=1851franchise.com&utm_medium=article&utm_campaign=fast-food-flops-and-failures-from-major-franchise-brands-2722290 (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Breitenbach, Z.; Raposa, B.; Szabó, Z.; Polyák, É.; Szács, Z.; Kubányi, J.; Figler, M. Examination of Hungarian college students’ eating habits, physical activity and body composition. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudry, K.M.; Ludwa, I.A.; Thomas, A.M.; Ward, W.E.; Falk, B.; Josse, A.R. First-year university is associated with greater body weight, body composition and adverse dietary changes in males than females. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriaučionienė, V.; Grincaitė, M.; Raskilienė, A.; Petkevičienė, J. Changes in Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Body Weight among Lithuanian Students during and after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehi, T.; Khan, R.; Halawani, R.; Dos Santos, H. Effect of COVID-19 outbreak on the diet, body weight and food security status of students of higher education: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2023, 129, 1916–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S.; Samuels, T.A.; Özcan, N.K.; Mantilla, C.; Rahamefy, O.H.; Wong, M.L.; Gasparishvili, A. Prevalence of overweight/obesity and its associated factors among university students from 22 countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7425–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whatnall, M.C.; Patterson, A.J.; Brookman, S.; Convery, P.; Swan, C.; Pease, S.; Hutchesson, M.J. Lifestyle behaviors and related health risk factors in a sample of Australian university students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 68, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrkou, C.; Tsakoumaki, F.; Fotiou, M.; Dimitropoulou, A.; Symeonidou, M.; Menexes, G.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Michaelidou, A.M. Changing Trends in Nutritional Behavior among University Students in Greece, between 2006 and 2016. Nutrients 2018, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Fang, Y.; Yan, W.; Gu, J.; Hao, Y.; Wu, C. Relationship between body dissatisfaction, insufficient physical activity, and disordered eating behaviors among university students in southern China. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Sun, S.; Lin, Z.; Fan, X. The association between body appreciation and body mass index among males and females: A meta-analysis. Body Image 2020, 34, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, Q.; Luo, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Sun, M.; Xi, Y.; Xiang, C.; Lin, Q. The Relationship between Restrained Eating, Body Image, and Dietary Intake among University Students in China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.; Bridges, S.K. The drive for muscularity in men: Media influences and objectification theory. Body Image 2010, 7, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, S.; Higgins, A. Muscle dysmorphia: An under-recognised aspect of body dissatisfaction in men. Br. J. Nurs. 2024, 33, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Anderberg, I. Muscles and Bare Chests on Instagram: The Effect of Influencers’ Fashion and Fitspiration Images on Men’s Body Image. Body Image 2020, 35, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rounsefell, K.; Gibson, S.; McLean, S.; Blair, M.; Molenaar, A.; Brennan, L.; Truby, H.; McCaffrey, T.A. Social Media, Body Image and Food Choices in Healthy Young Adults: A Mixed Methods Systematic Review. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, I.; Hernâni-Eusébio, J.; Silva, R. “How Many Likes?”: The Use of Social Media, Body Image Insatisfaction and Disordered Eating. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, S698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, J. The Effects of Physical and Psychological Well-Being on Suicidal Ideation. J. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 54, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoniccolo, F.; Trombetta, T.; Paradiso, M.N.; Rollè, L. Gender and Media Representations: A Review of the Literature on Gender Stereotypes, Objectification and Sexualization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, M.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Villanueva-Tobaldo, C.V.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. Body Perceptions and Psychological Well-Being: A Review of the Impact of Social Media and Physical Measurements on Self-Esteem and Mental Health with a Focus on Body Image Satisfaction and Its Relationship with Cultural and Gender Factors. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundgot-Borgen, C.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Bratland-Sanda, S.; Kolle, E.; Torstveit, M.K.; Svantorp-Tveiten, K.M.E.; Mathisen, T.F. Body appreciation and body appearance pressure in Norwegian university students comparing exercise science students and other students. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eck, K.M.; Quick, V.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Body Dissatisfaction, Eating Styles, Weight-Related Behaviors, and Health among Young Women in the United States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosendiak, A.A.; Adamczak, B.B.; Kuźnik, Z.; Makles, S. How Dietary Choices and Nutritional Knowledge Relate to Eating Disorders and Body Esteem of Medical Students? A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Morcillo, J.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Rodríguez-Besteiro, S.; Clemente-Suárez, V.J. The Association of Body Image Perceptions with Behavioral and Health Outcomes among Young Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskiene, R.; Baceviciene, M. Body Image Concerns and Body Weight Overestimation Do not Promote Healthy Behaviour: Evidence from Adolescents in Lithuania. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.A.; Rush, M.; Smith, G.T. Reciprocal relations between body dissatisfaction and excessive exercise in college women. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Towards active health: A study on the relationship between physical activity and body image among college students. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loth, K.A.; MacLehose, R.; Bucchianeri, M.; Crow, S.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Predictors of dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 55, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Male Students | Female Students | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithuania | Poland | p-Value | Lithuania | Poland | p-Value | |

| Age (years), median (IR) | 19 (2) | 20 (3) | 0.01 | 20 (4) | 20 (3) | 0.359 |

| Body Appreciation Scale (scores), median (IR) | 34 (10.8) | 35 (13.5) | 0.809 | 33 (12.5) | 32 (14) | 0.020 |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2), median (IR) | 23.3 (4.6) | 23.5 (4.1) | 0.834 | 22.3 (4.8) | 21.1 (4.1) | 0.001 |

| Sitting time (hours), median (IR) | 6 (4) | 8 (4) | 0.001 | 6 (4) | 8 (4) | 0.001 |

| Sleep duration (hours) | 7 (1) | 7 (2) | 0.001 | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 0.294 |

| Vegetable portions a day, median (IR) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | <0.001 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | <0.001 |

| Fruit portions a day, median (IR) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.001 | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | <0.001 |

| Breakfast (days a week), median (IR) | 5 (4) | 7 (3) | 0.025 | 5 (4) | 7 (3) | <0.001 |

| Consumption of food products at least several times a week (% of participants) | ||||||

| Fish | 43.1 | 14.9 | <0.001 | 36.7 | 7.8 | <0.001 |

| Porridge/Cereals | 62.5 | 47.9 | 0.010 | 58.6 | 62.6 | 0.208 |

| Legumes | 45.4 | 22.3 | <0.001 | 42.0 | 33.0 | <0.004 |

| Nuts and seeds | 65.3 | 32.2 | <0.001 | 56.6 | 39.8 | <0.001 |

| Sweets (chocolate, candies) | 60.2 | 56.2 | 0.476 | 56.6 | 65.0 | 0.008 |

| Sugary drinks (soda) | 53.2 | 52.1 | 0.836 | 35.1 | 40.7 | 0.077 |

| Fast food | 41.7 | 25.6 | 0.003 | 21.9 | 13.7 | 0.001 |

| Snacks (chips, roasted peanuts, etc.) | 51.4 | 42.1 | 0.103 | 31.2 | 27.6 | 0.220 |

| Perceptions and Behavior (% of participants) | ||||||

| Believe it is important to eat healthy | 46.8 | 51.2 | 0.430 | 62.1 | 61.1 | 0.755 |

| Worry about weight gain | 7.4 | 15.4 | <0.001 | 40.6 | 73.7 | <0.001 |

| Take care of health | 77.8 | 65.3 | 0.013 | 86.4 | 62.8 | <0.001 |

| Evaluate health as good | 81.5 | 62.0 | <0.001 | 77.9 | 67.8 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Sex | Lithuania | Poland | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p-Value | r | p-Value | r | p-Value | ||

| BMI | M | −0.008 | 0.912 | −0.284 | 0.002 | −0.120 | 0.028 |

| F | −0.276 | <0.001 | −0.186 | <0.001 | −0.209 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived weight | M | −0.133 | 0.051 | −0.387 | <0.001 | −0.232 | <0.001 |

| F | −0.386 | <0.001 | −0.362 | <0.001 | −0.372 | <0.001 | |

| Variable | Lithuania | Poland | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | CI | p-Value | β | CI | p-Value | β | CI | p-Value | |

| Breakfast frequency | 0.63 | 0.40; 0.86 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.69; 1.38 | <0.001 | 0.76 | 0.57; 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Vegetable daily portions | 0.75 | 0.16; 1.34 | 0.013 | 0.61 | 0.25; 0.97 | 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.32; 0.92 | <0.001 |

| Fruit daily portions | 0.73 | 0.13; 1.33 | 0.017 | 0.57 | 0.00; 1.13 | 0.049 | 0.64 | 0.24; 1.05 | 0.002 |

| Fish consumption | 1.65 | 0.86; 2.43 | <0.001 | 1.711 | 0.46; 2.96 | 0.007 | 1.66 | 0.98; 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Porridge consumption | 1.55 | 0.93; 2.17 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 0.39; 1.96 | 0.003 | 1.32 | 0.84; 1.81 | <0.001 |

| Legumes consumption | 1.68 | 0.97; 2.39 | <0.001 | 1.11 | 0.17; 2.05 | 0.020 | 1.41 | 0.84; 1.98 | <0.001 |

| Nuts consumption | 2.50 | 1.97; 3.03 | <0.001 | 1.70 | 0.84; 2.56 | <0.001 | 2.16 | 1.69; 2.62 | <0.001 |

| Sweets consumption | −1.83 | −2.49; −1.18 | <0.001 | −0.41 | −1.33; 0.51 | 0.381 | −1.30 | −1.84; −0.76 | <0.001 |

| Sugary drinks consumption | −1.58 | −2.21; −0.96 | <0.001 | 0.25 | −0.47; 0.97 | 0.495 | −0.68 | −1.16; −0.21 | 0.005 |

| Fast food consumption | −1.93 | −2.91; −0.95 | <0.001 | −0.28 | −1.76; 1.21 | 0.713 | −1.36 | −2.19; −0.53 | 0.001 |

| Snacks consumption | −1.22 | −2.05; −0.39 | 0.004 | −0.40 | 1.50; 0.69 | 0.468 | −0.89 | −1.56; −0.22 | 0.009 |

| Sitting hours | −0.38 | −0.57; −0.18 | <0.001 | −0.28 | −0.56; 0.01 | 0.057 | −0.34 | −0.50; −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Exercises during leisure time | −1.72 | −2.07; −1.38 | <0.001 | −0.52 | −0.97; −0.07 | 0.023 | −1.18 | −1.46; −0.89 | <0.001 |

| Sleep hours | 1.65 | 1.18; 2.12 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 0.70; 1.98 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.11; 1.87 | <0.001 |

| Health perception | −1.70 | −2.43; −0.97 | <0.001 | −4.43 | −5.30; −3.56 | <0.001 | −2.87 | −3.43; −2.30 | <0.001 |

| Taking care of health | 3.34 | 2.48; 4.20 | <0.001 | 3.67 | 2.76; 4.58 | <0.001 | 3.52 | 2.90; 4.14 | <0.001 |

| Worrying about weight gain | −2.67 | −3.18; −2.16 | <0.001 | −3.27 | −3.80; −2.74 | <0.001 | 2.97 | 2.60; 3.34 | <0.001 |

| Importance of eating healthily | −2.92 | −3.58; −2.27 | <0.001 | −2.59 | −3.35; −1.83 | <0.001 | −2.75 | −3.24; −2.26 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Unstandardized Coefficients | CI | p-Value | Standardized Coefficients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | −0.22 | −0.33; −0.11 | <0.001 | −0.10 |

| Fish consumption | 0.90 | 0.30; 1.50 | 0.003 | 0.08 |

| Nuts consumption | 1.36 | 0.93; 1.79 | <0.001 | 0.16 |

| Sweets consumption | −0.65 | −1.12; −0.18 | 0.006 | −0.06 |

| Exercises during leisure time | −0.60 | −0.85; −0.34 | <0.001 | −0.11 |

| Sleep hours | 0.92 | 0.59; 1.25 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Health perception | −2.08 | −2.58; −1.58 | <0.001 | −0.19 |

| Worrying about weight gain | −2.67 | −3.00; −2.33 | <0.001 | −0.42 |

| Age | 0.23 | 0.13; 0.32 | <0.001 | 0.11 |

| Gender (males vs. females) | 1.56 | 0.56; 2.56 | 0.002 | 0.08 |

| Country (Poland vs. Lithuania) | −3.40 | −4.31; −2.50 | <0.001 | −0.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kriaučionienė, V.; Gajewska, D.; Raskilienė, A.; Myszkowska-Ryciak, J.; Ponichter, J.; Paulauskienė, L.; Petkevičienė, J. Associations Between Body Appreciation, Body Weight, Lifestyle Factors and Subjective Health Among Bachelor Students in Lithuania and Poland: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3939. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223939

Kriaučionienė V, Gajewska D, Raskilienė A, Myszkowska-Ryciak J, Ponichter J, Paulauskienė L, Petkevičienė J. Associations Between Body Appreciation, Body Weight, Lifestyle Factors and Subjective Health Among Bachelor Students in Lithuania and Poland: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(22):3939. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223939

Chicago/Turabian StyleKriaučionienė, Vilma, Danuta Gajewska, Asta Raskilienė, Joanna Myszkowska-Ryciak, Julia Ponichter, Lina Paulauskienė, and Janina Petkevičienė. 2024. "Associations Between Body Appreciation, Body Weight, Lifestyle Factors and Subjective Health Among Bachelor Students in Lithuania and Poland: Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 16, no. 22: 3939. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223939

APA StyleKriaučionienė, V., Gajewska, D., Raskilienė, A., Myszkowska-Ryciak, J., Ponichter, J., Paulauskienė, L., & Petkevičienė, J. (2024). Associations Between Body Appreciation, Body Weight, Lifestyle Factors and Subjective Health Among Bachelor Students in Lithuania and Poland: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 16(22), 3939. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16223939