Dietary and Lifestyle Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

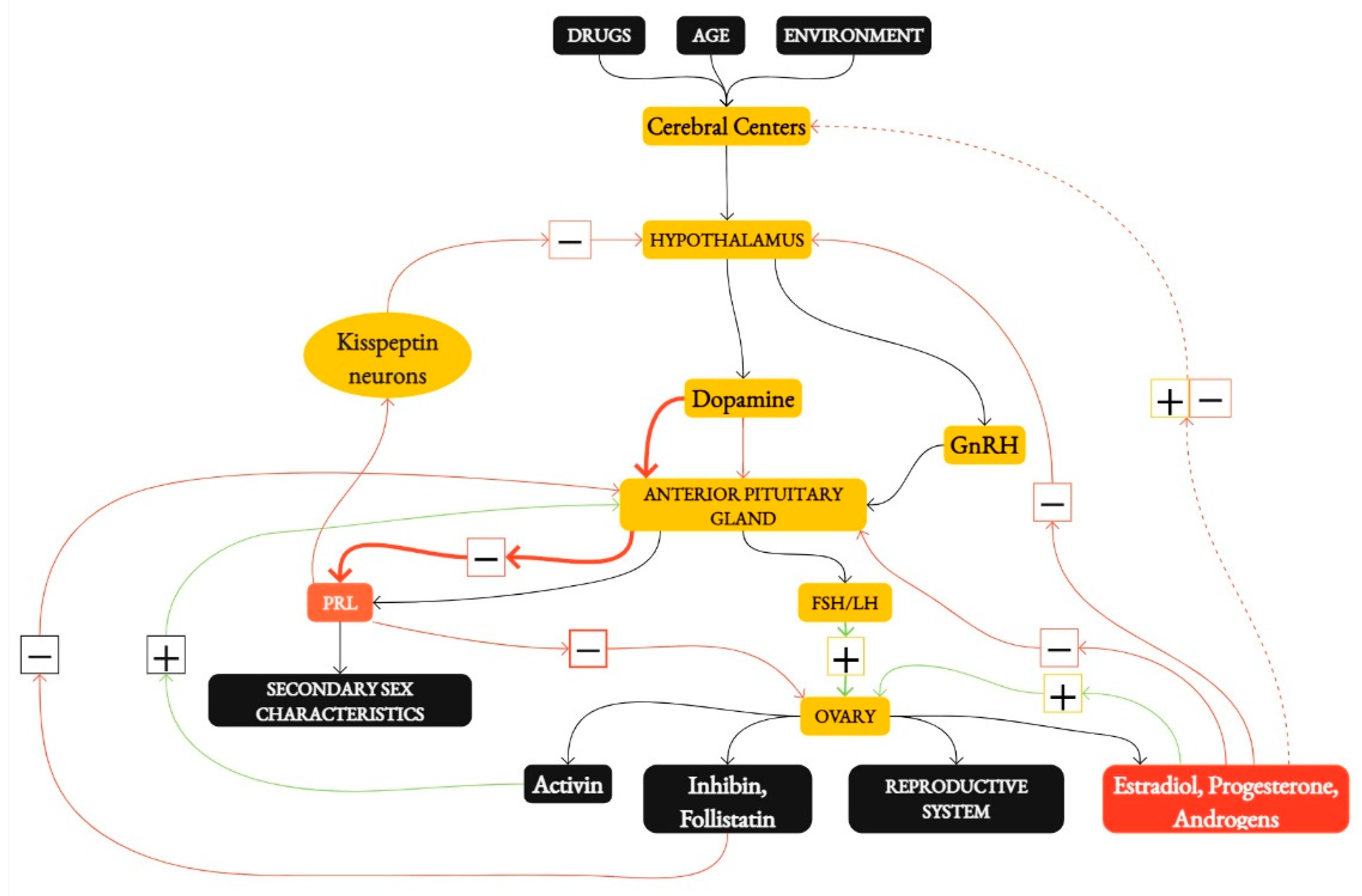

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Aim of Work

3. Results

3.1. The Impact of Energy Availability on the Menstrual Cycle

3.2. Dietary Intervention

3.3. The Role of Micronutrients in the Management of FHA

3.4. Psychological Interventions in FHA

3.5. Other Nutritional and Lifestyle Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loucks, A.B.; Thuma, J.R. Luteinizing hormone pulsatility is disrupted at a threshold of energy availability in regularly menstruating women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, J.L.; DE Souza, M.J.; Wagstaff, D.A.; Williams, N.I. Menstrual Disruption with Exercise Is Not Linked to an Energy Availability Threshold. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Considine, R.V. Female Reproductive System. In Medical Physiology: Principles for Clinical Medicine, 4th ed.; Rhoades, R., Bell, D.R., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 693–709. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P.B. Infrequent Menstrual Bleeding and Amenorrhea during the Reproductive Years. In Disorders of Menstruation; Marshburn, P.B., Hurst, B.S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2011; p. 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.E.S.; Fleming, N.; Zuijdwijk, C.; Dumont, T. Where Have the Periods Gone? The Evaluation and Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Berga, S.L.; Kaplan, J.R.; Mastorakos, G.; Misra, M.; Murad, M.H.; Santoro, N.F.; Warren, M.P. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1413–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meczekalski, B.; Katulski, K.; Czyzyk, A.; Podfigurna-Stopa, A.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and its influence on women’s health. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2014, 37, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podfigurna, A.; Meczekalski, B. Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Stress-Based Disease. Endocrines 2021, 2, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.B. Direct and indirect effects of leptin on adipocyte metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.L.; De Souza, M.J.; Mallinson, R.J.; Scheid, J.L.; I Williams, N. Energy availability discriminates clinical menstrual status in exercising women. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2015, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiga-Carvalho, T.M.; Oliveira, K.J.; Soares, B.A.; Pazos-Moura, C.C. The role of leptin in the regulation of TSH secretion in the fed state: In vivo and in vitro studies. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 174, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.P.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Fried, J.L. Amenorrhea, Osteoporosis, and Eating Disorders in Athletes. In Textbook of Sports Medicine: Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Sports Injury and Physical Activity; Kjaer, M., Krogsgaard, M., Magnusson, P., Engebretsen, L., Roos, H., Takala, T., Woo, S.L., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 462–480. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoletto, P.; Reichman, D. Secondary Amenorrhea. In Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice; Carrell, D.T., Peterson, C.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Koltun, K.J.; De Souza, M.J.; Scheid, J.L.; Williams, N.I. Energy availability is associated with luteinizing hormone pulse frequency and induction of luteal phase defects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current clinical irrelevance of luteal phase deficiency: A committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, e27–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.I.; Leidy, H.J.; Hill, B.R.; Lieberman, J.L.; Legro, R.S.; De Souza, M.J. Magnitude of daily energy deficit predicts frequency but not severity of menstrual disturbances associated with exercise and caloric restriction. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 308, E29–E39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Hitchcock, C.L.; Barr, S.I.; Yu, T.; Prior, J.C. Negative Spinal Bone Mineral Density Changes and Subclinical Ovulatory Disturbances—Prospective Data in Healthy Premenopausal Women With Regular Menstrual Cycles. Epidemiologic Rev. 2013, 36, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Sjödin, A.; Benardot, D.; Tornberg, Å.B.; Skouby, S.; Faber, J.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.K.; Melin, A.K. Within-day energy deficiency and reproductive function in female endurance athletes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryterska, K.; Kordek, A.; Załęska, P. Has Menstruation Disappeared? Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea—What Is This Story about? Nutrients 2021, 13, 2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.R.; Cardoso, G.; Brito, M.E.; Gomes, I.N.; Cascais, M.J. The female athlete Triad/Relative energy deficiency in sports (RED-S). Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2021, 43, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Mallinson, R.J.; A Strock, N.C.; Koltun, K.J.; Olmsted, M.P.; A Ricker, E.; Scheid, J.L.; Allaway, H.C.; Mallinson, D.J.; Don, P.K.; et al. Randomised controlled trial of the effects of increased energy intake on menstrual recovery in exercising women with menstrual disturbances: The ‘REFUEL’ study. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 2285–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łagowska, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Jeszka, J. Nine–month nutritional intervention improves restoration of menses in young female athletes and ballet dancers. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2014, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Ricker, E.A.; Mallinson, R.J.; Allaway, H.C.M.; Koltun, K.J.; Strock, N.C.; Gibbs, J.C.; Don, P.K.; Williams, N.I. Bone mineral density in response to increased energy intake in exercising women with oligomenorrhea/amenorrhea: The REFUEL randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, R.J.; Williams, N.I.; Olmsted, M.P.; Scheid, J.L.; Riddle, E.S.; De Souza, M.J. A case report of recovery of menstrual function following a nutritional intervention in two exercising women with amenorrhea of varying duration. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2013, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominato, L.; da Silva, M.M.X.; Steinmetz, L.; Pinzon, V.; Fleitlich-Bilyk, B.; Damiani, D. Menstrual cycle recovery in patients with anorexia nervosa: The importance of insulin-like growth factor 1. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2014, 82, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempfle, A.; Herpertz-Dahlmann, B.; Timmesfeld, N.; Schwarte, R.; Egberts, K.M.; Pfeiffer, E.; Fleischhaker, C.; Wewetzer, C.; Bühren, K. Predictors of the resumption of menses in adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukic, A.M.Z.; Wilcox, A.J.; McConnaughey, D.R.; Weinberg, C.R.; Steiner, A.Z. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Long Menstrual Cycles in a Prospective Cohort Study. Epidemiology 2018, 29, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Tamar, N.; Lone, Z.; Das, E.; Sahu, R.; Majumdar, S. Association between serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D level and menstrual cycle length and regularity: A cross-sectional observational study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2021, 19, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, M.; Klibanski, A. Endocrine consequences of anorexia nervosa. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, G.; Mazur, A.; Trousselard, M.; Bienkowski, P.; Yaltsewa, N.; Amessou, M.; Noah, L.; Pouteau, E. Magnesium status and stress: The vicious circle concept revisited. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parazzini, F.; Di Martino, M.; Pellegrino, P. Magnesium in the gynecological practice: A literature review. Magnes. Res. 2017, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, N.B.; Lawton, C.; Dye, L. The effects of magnesium supplementation on subjective anxiety and stress—A systematic review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Grandner, M.A.; Liu, J. The relationship between micronutrient status and sleep patterns: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, B.M.; Georgieff, M.K. The Interaction between Psychological Stress and Iron Status on Early-Life Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Diaz, F.J. Zinc depletion causes multiple defects in ovarian function during the periovulatory period in mice. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopresti, A.L. The effects of psychological and environmental stress on micronutrient concentrations in the body: A review of the evidence. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranoulis, A.; Soldatou, A.; Georgiou, D.; Mavrogianni, D.; Loutradis, D.; Michala, L. Adolescents and young women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea: Is it time to move beyond the hormonal profile? Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berga, S.L.; Marcus, M.D.; Loucks, T.L.; Hlastala, S.; Ringham, R.; A Krohn, M. Recovery of ovarian activity in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea who were treated with cognitive behavior therapy. Fertil. Steril. 2003, 80, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimi, O.; Cameron, L.-C. Effect of exercise on ovulation: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duclos, M.; Tabarin, A. Exercise and the Hypothalamo-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Sports Endocrinol. 2016, 47, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.C. Exercise as a stressor to the human neuroendocrine system. Medicina 2006, 1, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.M.; Kawwass, J.F.; Loucks, T.; Berga, S.L. Heightened cortisol response to exercise challenge in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 230.e1–230.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhmann, K. Menses Requires energy: A review of how disordered eating, excessive exercise, and high stress lead to menstrual irregularities. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Caetano, L.; Anastasiadou, N.; Karasu, T.; Lashen, H. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhoea: Leptin treatment, dietary intervention and counselling as alternatives to traditional practice—Systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 198, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Farahani, L.; Webber, L.; Jayasena, C. Current understanding of hypothalamic amenorrhoea. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 11, 2042018820945854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed-Abdul, M.M.; Soni, D.S.; Wagganer, J.D. Impact of a Professional Nutrition Program on a Female Cross Country Collegiate Athlete: A Case Report. Sports 2018, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loucks, A.B.; Kiens, B.; Wright, H.H. Energy availability in athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29 (Suppl. S1), S7–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.; Burke, L.; Carter, S.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Meyer, N.; Sherman, R.; Steffen, K.; Budgett, R.; et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loucks, A.B.; Verdun, M.; Heath, E.M. Low energy availability, not stress of exercise, alters LH pulsatility in exercising women. J. Appl. Physiol. 1998, 84, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joy, E.; De Souza, M.J.; Nattiv, A.; Misra, M.; Williams, N.I.; Mallinson, R.J.; Gibbs, J.C.; Olmsted, M.; Goolsby, M.; Matheson, G.; et al. 2014 Female athlete triad coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2014, 13, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.R.; Paiva, T. Low energy availability and low body fat of female gymnasts before an international competition. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2015, 15, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, A.; Tornberg, Å.B.; Skouby, S.; Faber, J.; Ritz, C.; Sjödin, A.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. The LEAF questionnaire: A screening tool for the identification of female athletes at risk for the female athlete triad. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, B.; Rosenbloom, C. Fundamentals of glycogen metabolism for coaches and athletes. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.M.; Hawley, J.A.; Wong, S.H.S.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Carbohydrates for training and competition. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29 (Suppl. S1), S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, S.L.; Chavarro, J.E.; Zhang, C.; Perkins, N.J.; Sjaarda, L.A.; Pollack, A.Z.; Schliep, K.C.; A Michels, K.; Zarek, S.M.; Plowden, T.C.; et al. Dietary fat intake and reproductive hormone concentrations and ovulation in regularly menstruating women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz, M.; Rychlik, E.; Stoś, K.; Charzewska, J. Normy Żywienia dla Populacji Polski i ich Zastosowanie (eng. Nutrition Standards for the Polish Population and Their Application), 1st ed.; Narodowy Instytut Zdrowia Publicznego-Państwowy Zakład Higieny: Warsaw, Poland, 2020; pp. 68–437. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, K.D.; Ayuketah, A.; Brychta, R.; Cai, H.; Cassimatis, T.; Chen, K.Y.; Chung, S.T.; Costa, E.; Courville, A.; Darcey, V.; et al. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 67–77.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Energy Availability (EA) Levels | Findings on LH Pulses | Findings on Menstrual Disorders | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loucks et al. [1] | 30 kcal/kg FFM/day 20 kcal/kg FFM/day 10 kcal/kg FFM/day | −20 kcal/kg FFM/day, 16% decrease in LH pulse frequency, a 21% increase in amplitude, −10 kcal/kg FFM/day, 39% decrease in LH pulse frequency, 109% increase in amplitude | EA below 30 kcal/kg FFM/day is linked to a higher likelihood of menstrual disorders, such as oligo/amenorrhea | Establishes a threshold for EA below which LH pulsatility and menstrual function are impaired |

| Koltun et al. [14] | No specific threshold identified. Reduction from 38 to 28 kcal/kg FFM/day | Decrease in LH pulse frequency by 0.017 pulses/hour for each unit decrease in EA. Lower EA also significantly reduces LH secretion frequency | Increased risk of luteal phase defects with lower EA. Significant EA reductions heighten the likelihood of menstrual disorders | No clear threshold for EA, but findings suggest more severe impacts with greater EA reduction |

| Liberman et al. [2] | EA < 30 kcal/kg FFM/day | LH pulse frequency decreases and amplitude increases with reduced EA | Menstrual disorders (luteal phase defects, anovulation, oligomenorrhea) become more likely as EA decreases but can occur even above 30 kcal/kg FFM/day | Highlights that menstrual disorders can occur even above 30 kcal/kg FFM/day, challenging the strict threshold concept |

| Reed et al. [10] | FHA group: 30.9 ± 2.4 kcal/kg FFM/day vs. 36.9 ± 1.7 kcal/kg FFM/day in control | No specific findings on LH pulses were provided | Women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA)had significantly lower EA compared to regularly menstruating women | EA of 30 kcal/kg FFM/day does not clearly differentiate between regular menstruation and menstrual disorders |

| Study | Population | Intervention | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Souza et al. [20] | Thirty-three women (age 18–35) with secondary amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea, BMI 16–25 kg/m2, exercising >2 h/week | Increased caloric intake by 330 ± 65 kcal/day (20–40%) over 12 months | Weight gain: 2.6 ± 0.4 kg, Fat mass gain: 2.0 ± 0.3 kg, Increase in T3 concentration by 9 ± 4 ng/dL | A modest caloric surplus (~300–350 kcal/day) is sufficient for restoring menstrual cycles. Improved energy balance leads to menstrual recovery |

| Łagowska et al. [21] | Fifty-two athletes and ballet dancers with menstrual disorders, training >4 times/week | Increased caloric intake by 20–30%, energy availability increased by >30 kcal/kg FFM/day over 9 months | Weight gain: 1.3 kg (ballet dancers), no significant weight changes (athletes), Increased LH and LH/FSH ratio, Menstrual recovery in 3 dancers and 7 athletes | Increased caloric intake is critical for hormonal improvement and menstrual recovery. Menstrual function can be restored when body fat mass reaches 22% |

| Mallinson et al. [23] | Two women with FHA of different durations | A 12-month nutritional intervention with individualized caloric increases | Weight gain: 4.3 kg (long-term FHA) and 2.8 kg (short-term FHA), Improvements in leptin and T3 concentrations | Weight gain and improved hormone levels are crucial for menstrual recovery, with individual variations of response |

| Cominato et al. [24] | Adolescents with eating disorders | A 20-week nutritional intervention | Recovery of menstrual function linked to increases in BMI, LH, IGF-1, and estradiol | IGF-1 may serve as a potential marker for menstrual recovery. Nutritional rehabilitation is a key to restoring menstrual function |

| Deampfle et al. [25] | One hundred and fifty-two girls (age 11–18) with eating disorders and underweight | Observational study followed participants over 12 months | Forty-seven percent regained menstrual function, Strong correlation between %EBW and resumption of menstruation | Achieving expected body weight is strongly associated with menstrual recovery. BMI is not a reliable predictor of menstrual function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dobranowska, K.; Plińska, S.; Dobosz, A. Dietary and Lifestyle Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172967

Dobranowska K, Plińska S, Dobosz A. Dietary and Lifestyle Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(17):2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172967

Chicago/Turabian StyleDobranowska, Katarzyna, Stanisława Plińska, and Agnieszka Dobosz. 2024. "Dietary and Lifestyle Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Comprehensive Review" Nutrients 16, no. 17: 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172967

APA StyleDobranowska, K., Plińska, S., & Dobosz, A. (2024). Dietary and Lifestyle Management of Functional Hypothalamic Amenorrhea: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients, 16(17), 2967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172967