A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Study

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Instruments

- Demographic and health information. Name, surname, date of birth, age, educational qualification, profession, marital status, weight, and height. To calculate the Body Mass Index (BMI), the weight in kilograms was divided by the squared value of the height in meters (kg/m2).

- Eating-behavior symptomatology. Patients completed the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, 6th edition (EDEQ 6.0) [53], a 28-item questionnaire examining eating-behavior symptoms in the previous 28 days. Items 1 to 12 and 19 to 28 provide a response on scales of frequency or intensity from 0 to 6, ranging from “never” to “every day” or from “none” to “extreme”. These items are summed into four subscales: restriction, concern about food, weight concern, and concern for body shape. A global scale is obtained by summing the four subscales and dividing them by 4. The four subscales are scored, and the general scores are consistent with the presence of an eating disorder when above the z-score of 1.5. The Italian translation by Dalle Grave and Calugi was used in this study [54], showing good reliability (α = 0.89).

- Binge-eating disorder symptomatology. The Binge-Eating Scale (BES) is a 16-item questionnaire that explores behaviors, feelings, and thoughts related to an episode of binge eating (e.g., “Sometimes I feel like I’m gulping down food. Despite this, I never end up feeling too full”). For each item, subjects can choose the statement that best represents them among the four proposed. After recoding, responses are summed together into a total score: scores below 17 indicate no or unlikely binge eating; between 17 and 27, possible or mild binge eating; and above 27, probable or severe binge eating. The scale has been translated, adapted, and validated in Italian contexts. In this study, BES showed good internal consistency (α = 0.89).

- Eating self-efficacy. The Eating Self-Efficacy Brief Scale (ESEBS) [55] is an 8-item questionnaire that measures self-efficacy in regulating eating, defined as the extent to which one feels able to self-regulate relating to food. Answers are rated on a scale of 0 to 5, ranging from “not at all easy” to “completely easy”. The responses are summed on two factors: social self-efficacy, which measures the ability to regulate eating in social contexts (e.g., “How easy would it be for you to resist the urge to eat when eating out with friends”), and emotional self-efficacy, the ability to resist in situations of emotional activation (e.g., “How easy would it be for you to resist the urge to eat when you are worried about work/study reasons”). Both factors showed good internal consistency in this sample (social self-efficacy, α = 0.86; emotional self-efficacy, α = 0.79).

- Psychopathological distress. The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) [56] explores the presence of psychological symptoms related to nine areas of functioning plus an overall score. It consists of 90 questions about different symptoms (e.g., “Headache”; “Difficulty remembering things”), and the subject should indicate, on a scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”), the intensity with which they have suffered from the symptom in the past week. The Italian version of the SCL-90-R [57] has been translated, adapted, and validated in a general sample of adolescents and adults. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.97.

- Self-esteem. The Italian version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [58,59] is a questionnaire consisting of 10 statements that measure how the subject evaluates himself (e.g., “I think I have a number of qualities”) on a 4-point scale of agreement, from 4 = strongly disagree, to 1 = strongly agree, for items 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10 and from 1 = strongly disagree, to 4 = strongly agree, for items 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7. Higher scores indicate a higher self-esteem. The questionnaire showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86).

2.6. Hypotheses

2.6.1. Primary Outcomes

2.6.2. Secondary Outcomes

2.6.3. Maintenance of the Post-Intervention Changes

2.7. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives

3.2. Efficacy of Web-Based Group Intervention

3.3. One-Month Follow-Up for the Web-Based Group Intervention

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Text Rev. DSM-5®); APA: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders in Europe. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Binge Eating Disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the Burden of Eating Disorders: Mortality, Disability, Costs, Quality of Life, and Family Burden. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000–2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJong, H.; Broadbent, H.; Schmidt, U. A Systematic Review of Dropout from Treatment in Outpatients with Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Hindle, A.; Brennan, L. Dropout from Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Eating Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, M.; Keshishian, A.; Song, S.; Moskowitz, R.; Bulik, C.M.; Roos, C.R.; Levinson, C.A. Predictors of Relapse in Eating Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2023, 158, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, C.M.; Sullivan, P.F.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic and Environmental Contributions to Obesity and Binge Eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 33, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Zwaan, M. Binge Eating Disorder and Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2001, 25, S51–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCuen-Wurst, C.; Ruggieri, M.; Allison, K.C. Disordered Eating and Obesity: Associations between Binge-Eating Disorder, Night-Eating Syndrome, and Weight-related Comorbidities. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1411, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, L.M.; Nizzoli, U.; Bosello, O.; Melchionda, N.; Spera, G.; Cuzzolaro, M.; SISDCA. Manuale per la Cura e la Prevenzione dei Disturbi Dell’Alimentazione e Delle Obesità (DA&O); SICS, Ed.; TXT SpA: Limena, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and Overweight; Fact Sheet No. 311; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PASSI, S. Progressi Delle Aziende Sanitarie per la Salute in Italia. 2006. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi/ (accessed on 26 July 2019).

- Hamilton, A.; Mitchison, D.; Basten, C.; Byrne, S.; Goldstein, M.; Hay, P.; Heruc, G.; Thornton, C.; Touyz, S. Understanding Treatment Delay: Perceived Barriers Preventing Treatment-Seeking for Eating Disorders. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2022, 56, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigas, G.; Williams, K.; Sumithran, P.; Brown, W.A.; Swinbourne, J.; Purcell, K.; Caterson, I.D. Delays in Healthcare Consultations about Obesity—Barriers and Implications. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monaghesh, E.; Hajizadeh, A. The Role of Telehealth during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Systematic Review Based on Current Evidence. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Linardon, J.; Courtet, P.; Guillaume, S. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating Disorder Risk and Symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baenas, I.; Caravaca-Sanz, E.; Granero, R.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Testa, G.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Treasure, J.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. COVID-19 and Eating Disorders during Confinement: Analysis of Factors Associated with Resilience and Aggravation of Symptoms. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Opitz, M.-C.; Peebles, A.I.; Sharpe, H.; Duffy, F.; Newman, E. A Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of COVID-19 on Individuals with Eating Disorders in the UK. Appetite 2021, 156, 104977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCombie, C.; Austin, A.; Dalton, B.; Lawrence, V.; Schmidt, U. “Now It’s Just Old Habits and Misery”–Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on People With Current or Life-Time Eating Disorders: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 589225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteleone, A.M.; Cascino, G. A Systematic Review of Network Analysis Studies in Eating Disorders: Is Time to Broaden the Core Psychopathology to Non Specific Symptoms. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, V.; Bertelli, S.; Tedesco, R.; Anselmetti, S.; Priori, A.; Gambini, O.; Demartini, B. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19-Related Lockdown Measures among a Sample of Italian Patients with Eating Disorders: A Preliminary Longitudinal Study. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springall, G.; Caughey, M.; Zannino, D.; Cheung, M.; Burton, C.; Kyprianou, K.; Yeo, M. Family-Based Treatment for Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa: A Long-Term Psychological Follow-Up. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2022, 58, 1642–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgül, S.; Akdemir, D.; Nalbant, K.; Derman, O.; Ersöz Alan, B.; Tüzün, Z.; Kanbur, N. The Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Adolescents with an Eating Disorder and Identifying Factors Predicting Disordered Eating Behaviour. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2022, 16, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark Bryan, D.; Macdonald, P.; Ambwani, S.; Cardi, V.; Rowlands, K.; Willmott, D.; Treasure, J. Exploring the Ways in Which COVID-19 and Lockdown Has Affected the Lives of Adult Patients with Anorexia Nervosa and Their Carers. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2020, 28, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, P.; Donini, L.M. Eating Disorders and Obesity (ED&O) in the COVID-19 Storm. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowpertwait, L.; Clarke, D. Effectiveness of Web-Based Psychological Interventions for Depression: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2013, 11, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.D.; Cuijpers, P.; Muñoz, R.F.; Baumeister, H. Prevention of Mental Health Disorders Using Internet- and Mobile-Based Interventions: A Narrative Review and Recommendations for Future Research. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalumpundi, V.; Saeidzadeh, S.; Chi, N.-C.; Nair, R.; Gilbertson-White, S. The Efficacy of Web or Mobile-Based Interventions to Alleviate Emotional Symptoms in People with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 3029–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, G.; Gizzarelli, T.; Moghimi, E.; Vazquez, G.; Alavi, N. Online Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (ECBT) for the Management of Depression Symptoms in Unipolar and Bipolar Spectrum Disorders, a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 341, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, G.; Meartsi, D.; Nikjoo, N.; Sajid, S.; Moghimi, E.; Alavi, N. Online Psychotherapy for the Management of Alcohol Use Disorder, a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dölemeyer, R.; Klinitzke, G.; Steinig, J.; Wagner, B.; Kersting, A. Working Alliance in Internet-Based Therapy for Binge Eating Disorder. Psychiatr. Prax. 2013, 40, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucas, C.E.; Fairburn, C.G.; Whittington, C.; Pennant, M.E.; Stockton, S.; Kendall, T. E-Therapy in the Treatment and Prevention of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 63, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linardon, J.; Shatte, A.; Messer, M.; Firth, J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. E-Mental Health Interventions for the Treatment and Prevention of Eating Disorders: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghimi, E.; Davis, C.; Rotondi, M. The Efficacy of EHealth Interventions for the Treatment of Adults Diagnosed with Full or Subthreshold Binge Eating Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Högdahl, L.; Birgegård, A.; Norring, C.; de Man Lapidoth, J.; Franko, M.A.; Björck, C. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Bulimic Eating Disorders in a Clinical Setting: Results from a Randomized Trial with One-Year Follow-Up. Internet Interv. 2023, 31, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melisse, B.; van den Berg, E.; de Jonge, M.; Blankers, M.; van Furth, E.; Dekker, J.; Beurs, E. de Efficacy of Web-Based, Guided Self-Help Cognitive Behavioral Therapy–Enhanced for Binge Eating Disorder: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment. In NICE Guide; 2020; Volume 62, pp. 1–42. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- APA. American Psychiatric Association Guideline Statements and Implementation. In The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Eating Disorders; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, C.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Attia, E.; Boland, R.; Escobar, J.; Fornari, V.; Golden, N.; Guarda, A.; Jackson-Triche, M.; Manzo, L.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2023, 180, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Virgilio, G.; Coclite, D.; Napoletano, A.; Barbina, D.; Dalla Ragione, L.; Spera, G.; Di Fiandra, T. Conferenza di Consenso. Disturbi del Comportamento Alimentare (DCA) Negli Adolescenti e nei Giovani Adulti; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Safer, D.L.; Telch, C.F.; Chen, E.Y.; Barone, L. Binge Eating e Bulimia: Trattamento Dialettico-Comportamentale; Raffaello Cortina: Roma, Italy, 2011; ISBN 8860303796. [Google Scholar]

- Safer, D.L.; Telch, C.F.; Chen, E.Y. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating and Bulimia; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 1606232657. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. The Eating Disorder Examination: A Semi-structured Interview for the Assessment of the Specific Psychopathology of Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S.; Ricca, V.; Castellini, G.; Lo Sauro, C.; Ruocco, A.; Chignola, E.; El Ghoch, M.; Dalle Grave, R. The Eating Disorder Examination: Reliability and Validity of the Italian Version. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2015, 20, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Crosby, R.D.; Machado, P.P.P. A Systematic Review of Instruments for the Assessment of Eating Disorders among Adults. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 0898620341. [Google Scholar]

- Panos, P.T.; Jackson, J.W.; Hasan, O.; Panos, A. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review Assessing the Efficacy of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2014, 24, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.; Carpenter, D.; Tang, C.Y.; Goldstein, K.E.; Avedon, J.; Fernandez, N.; Mascitelli, K.A.; Blair, N.J.; New, A.S.; Triebwasser, J.; et al. Dialectical Behavior Therapy Alters Emotion Regulation and Amygdala Activity in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 57, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozakou-Soumalia, N.; Dârvariu, Ş.; Sjögren, J.M. Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Improves Emotion Dysregulation Mainly in Binge Eating Disorder and Bulimia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of Eating Disorders: Interview or Self-Report Questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S.; Milanese, C.; Sartirana, M.; El Ghoch, M.; Sartori, F.; Geccherle, E.; Coppini, A.; Franchini, C.; Dalle Grave, R. The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire: Reliability and Validity of the Italian Version. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2017, 22, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Alivernini, F.; Ballesio, A.; Violani, C.; Fernandes, M.; Lucidi, F. Eating Self-Efficacy: Validation of a New Brief Scale. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, L.R. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual; National Computer Systems Inc.: Minneap, MN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Prunas, A.; Sarno, I.; Preti, E.; Madeddu, F.; Perugini, M. Psychometric Properties of the Italian Version of the SCL-90-R: A Study on a Large Community Sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezza, M.; Trombaccia, F.R.; Armento, L. La Scala Dell’autostima Di Rosenberg: Traduzione e Validazione Italiana. Giunti Organ. Spec. 1997, 223, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Accept. Commit. Ther. Meas. Packag. 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner, L.; Timm, C.; Barnow, S.; Rubel, J.A.; Lalk, C.; Hartmann, S. Effectiveness of a Web-Based Cognitive Behavioral Self-Help Intervention for Binge Eating Disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2411127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, S.; Burton, A.L.; Cunich, M.; Hay, P.; Hazelton, J.L.; Kim, M.; Lymer, S.; Madden, S.; Maloney, D.; Miskovic-Wheatley, J.; et al. A Randomised Controlled Trial of Clinician Supported vs Self-Help Delivery of Online Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 329, 115534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakeman, R.; King, P.; Hurley, J.; Tranter, R.; Leggett, A.; Campbell, K.; Herrera, C. Towards Online Delivery of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 31, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, T.A.; Stiles, W.B. Some Problems with Randomized Controlled Trials and Some Viable Alternatives. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2016, 23, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khraisat, B.R.; Al-Jeady, A.M.; Alqatawneh, D.A.; Toubasi, A.A.; AlRyalat, S.A. The Prevalence of Mental Health Outcomes among Eating Disorder Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2022, 48, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Sample | Intervention | TAU | t-Test/χ² Test (df) | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)/n | Mean (SD)/n | Mean (SD)/n | |||

| Gender | 10 m; 55 f | 6 m; 37 f | 4 m; 18 f | 0.20 (1) | Phi coefficient = 0.055 |

| Age | 38.51 (13.15) | 37.7 (13.05) | 40.09 (13.51) | 0.691 (63) | Cohen’s d = 0.181 |

| BMI | 37.85 (9.59) | 38.75 (10.43) | 36.21 (7.81) | −0.995 (60) | Cohen’s d = −0.264 |

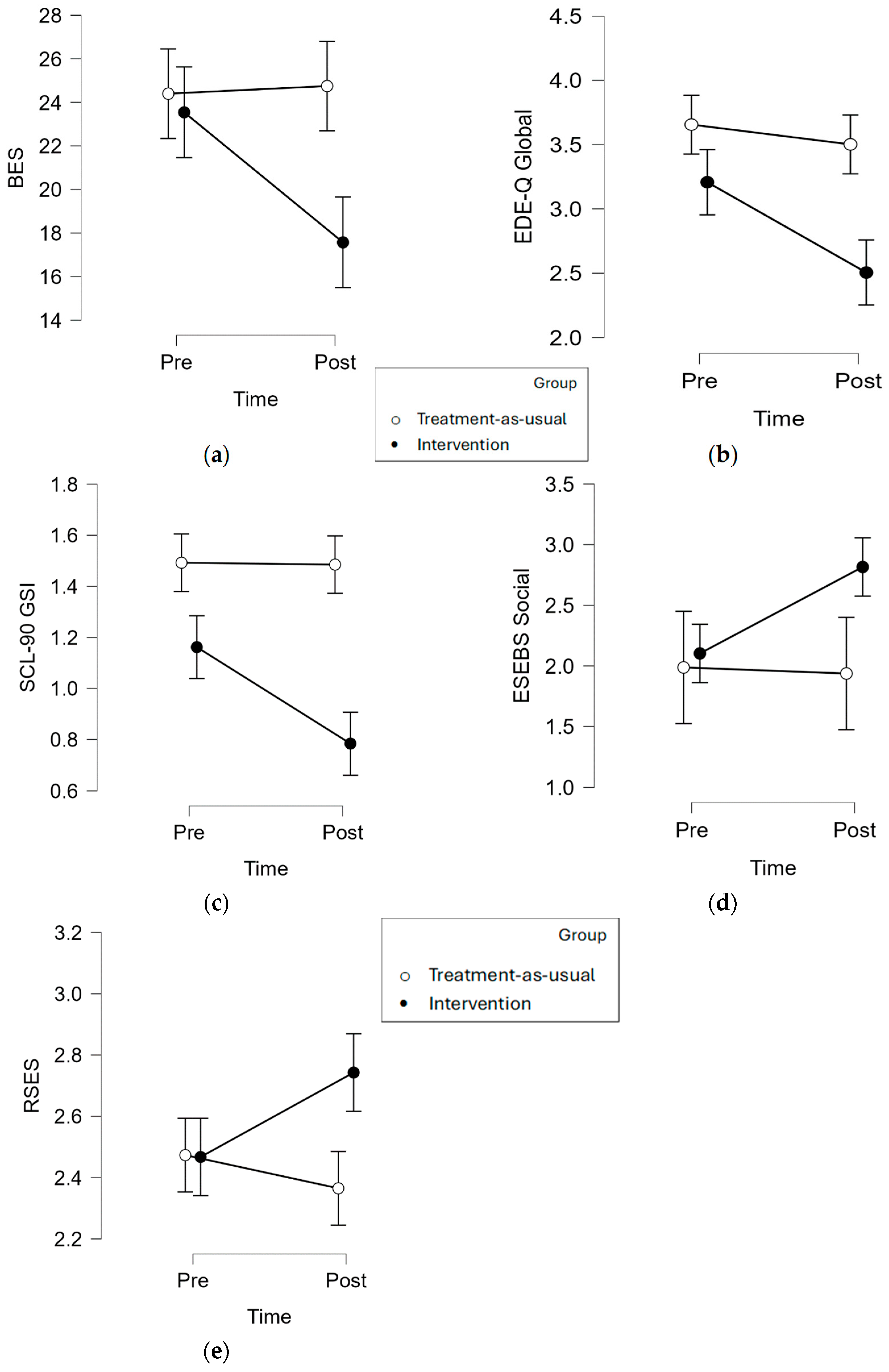

| Intervention (n = 43) | TAU (n = 22) | Moment × Group Interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | F Value | p | ηp2 |

| BMI | 0.028 [1, 51] | 0.868 | 0.001 | ||

| Pre | 39.4 (1.7) | 36.9 (2.2) | |||

| Post | 38.8 (1.8) | 36.3 (2.3) | |||

| BES | 8.357 [1, 53] | 0.006 | 0.136 | ||

| Pre | 23.5 (1.7) | 24.4 (2.2) | |||

| Post | 17.6 (1.7) | 24.7 (2.3) | |||

| SCL-90-R GSI | 8.729 [1, 54] | 0.005 | 0.139 | ||

| Pre | 1.16 (0.10) | 1.49 (0.13) | |||

| Post | 0.78 (0.08) | 1.49 (0.10) | |||

| EDEQ Global | 4.487 [1, 52] | 0.039 | 0.079 | ||

| Pre | 3.20 (0.21) | 3.66 (0.28) | |||

| Post | 2.50 (0.20) | 3.50 (0.25) | |||

| ESEBS Social | 5.561 [1, 52] | 0.022 | 0.097 | ||

| Pre | 2.10 (0.25) | 1.99 (0.32) | |||

| Post | 2.82 (0.25) | 1.94 (0.32) | |||

| ESEBS Emotional | 0.889 [1, 52] | 0.350 | 0.017 | ||

| Pre | 1.01 (0.19) | 1.01 (0.25) | |||

| Post | 1.82 (0.22) | 1.46 (0.29) | |||

| RSES | 8.482 [1, 53] | 0.005 | 0.138 | ||

| Pre | 2.47 (0.09) | 2.47 (0.12) | |||

| Post | 2.74 (0.091) | 2.36 (0.12) | |||

| Post-Intervention | One-Month Follow-Up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t Value (df) | Cohen’s d | |

| BES | 19.286 (10.311) | 17.333 (10.389) | 2.396 * (20) | 0.523 |

| EDEQ Global | 2.700 (1.206) | 2.423 (1.055) | 2.336 * (16) | 0.567 |

| SCL-90-R GSI | 0.804 (0.444) | 0.732 (0.425) | 2.181 * (20) | 0.476 |

| ESEBS Social | 2.594 (1.147) | 2.656 (1.161) | −0.207 (15) | −0.052 |

| RSES | 2.618 (0.631) | 2.582 (0.547) | 0.365 (16) | 0.089 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cerolini, S.; D’Amico, M.; Zagaria, A.; Mocini, E.; Monda, G.; Donini, L.M.; Lombardo, C. A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162696

Cerolini S, D’Amico M, Zagaria A, Mocini E, Monda G, Donini LM, Lombardo C. A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology. Nutrients. 2024; 16(16):2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162696

Chicago/Turabian StyleCerolini, Silvia, Monica D’Amico, Andrea Zagaria, Edoardo Mocini, Generosa Monda, Lorenzo Maria Donini, and Caterina Lombardo. 2024. "A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology" Nutrients 16, no. 16: 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162696

APA StyleCerolini, S., D’Amico, M., Zagaria, A., Mocini, E., Monda, G., Donini, L. M., & Lombardo, C. (2024). A Brief Online Intervention Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy for a Reduction in Binge-Eating Symptoms and Eating Pathology. Nutrients, 16(16), 2696. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16162696