Eating Styles Profiles and Correlates in Chinese Postpartum Women: A Latent Profile Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

2.2.2. Perceived Weight Stigma Questionnaire (PWSQ)

2.2.3. Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS)

2.2.4. Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS)

2.2.5. Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ)

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.3.2. Latent Profile Analysis

2.3.3. Single-Factor and Multi-Factor Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Result

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Results of Latent Profile Analysis

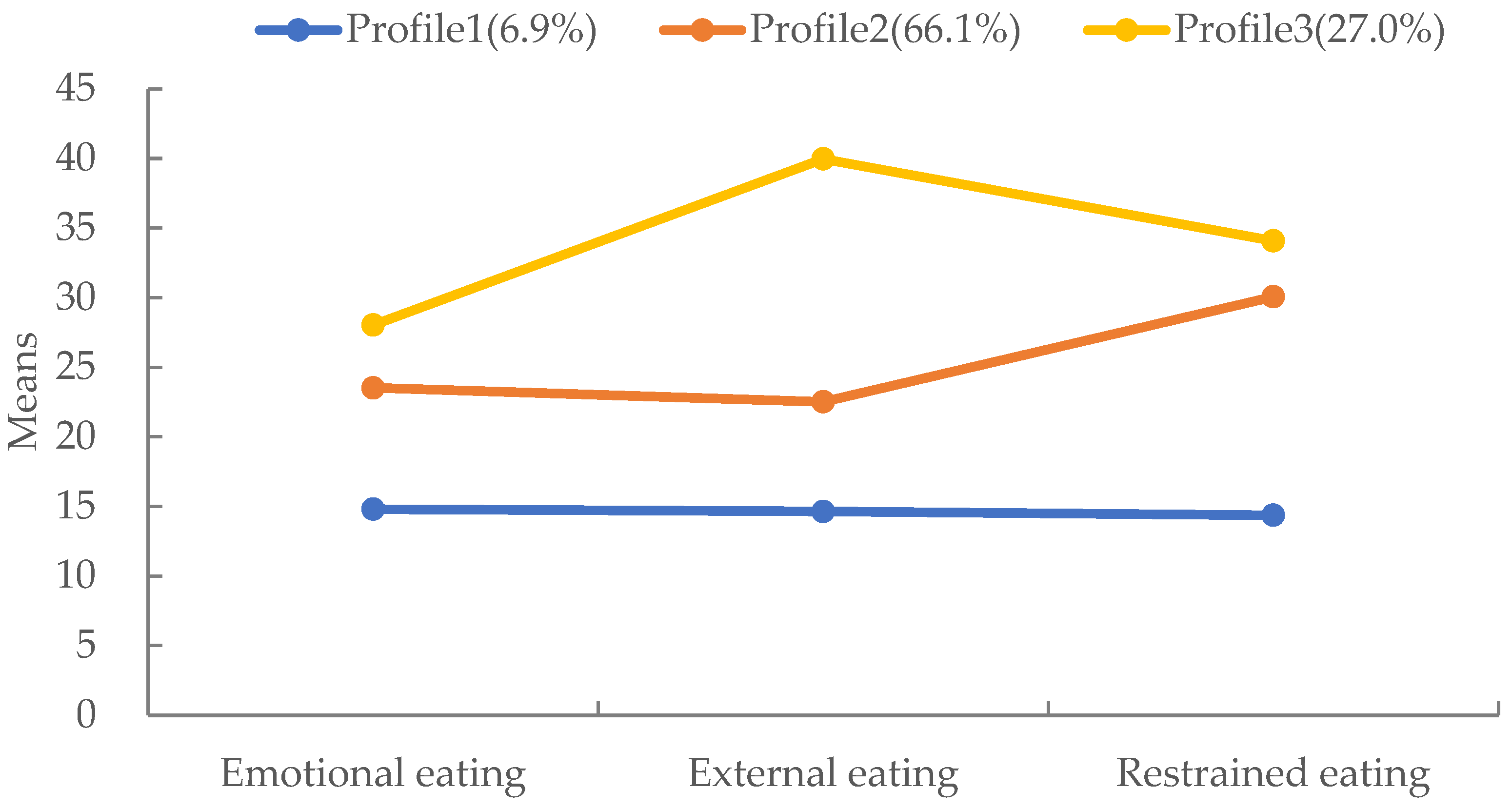

3.3. Categories of Latent Profile

3.4. Inter-Profile Characteristic Differences

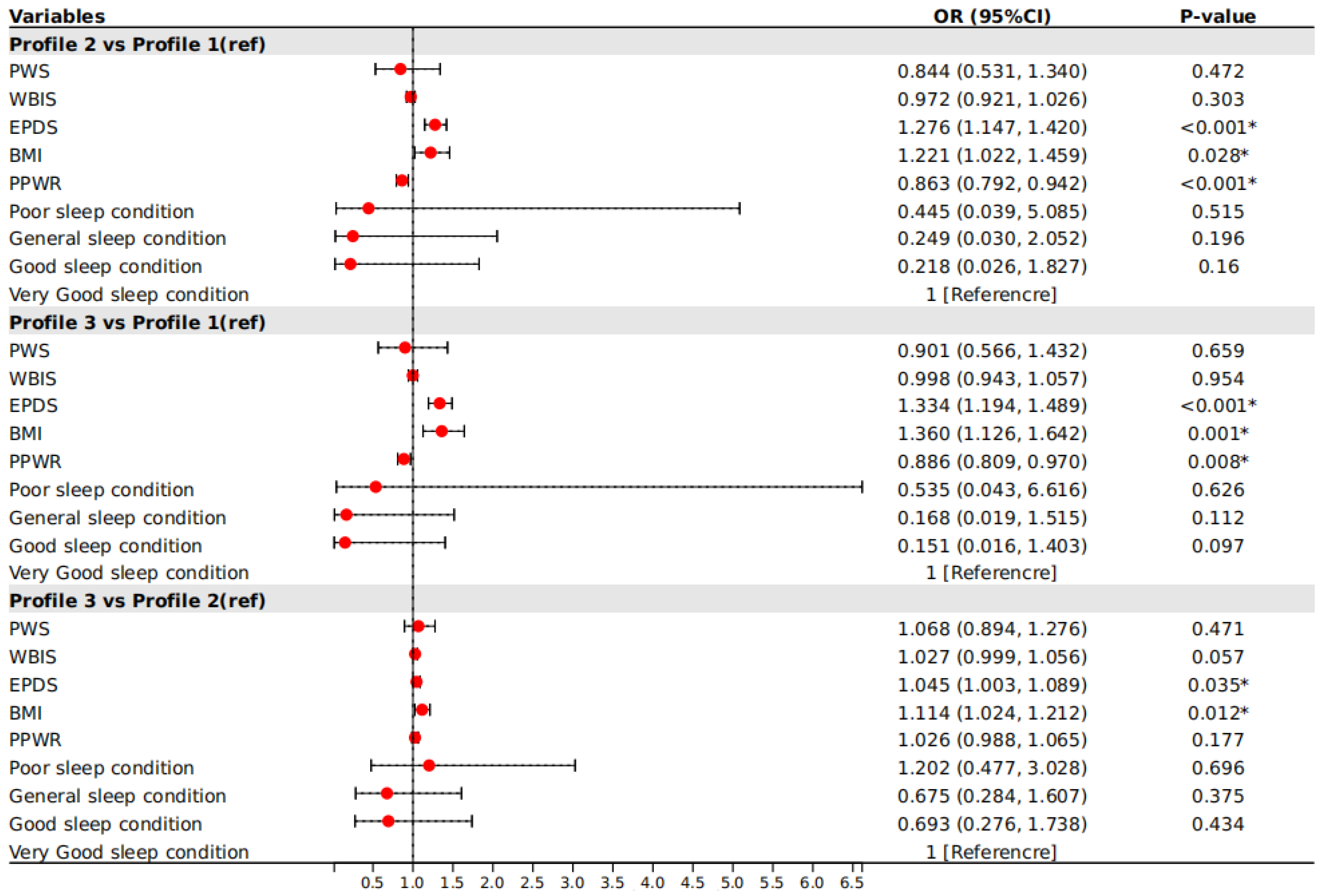

3.5. Multinomial Logistic Regression of Eating Styles Profiles

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 January 2024).

- WHO. WHO Acceleration Plan to Stop Obesity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, M.; Sundararajan, E.A.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W.; Shapi’i, A. A systematic literature review on obesity: Understanding the causes & consequences of obesity and reviewing various machine learning approaches used to predict obesity. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, J.; Hakala, P.; Isolauri, E.; Poussa, T.; Laitinen, K. Eating behavior influences diet, weight, and central obesity in women after pregnancy. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.; Mitchison, D. Eating Disorders and Obesity: The Challenge for Our Times. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Biggers, J.; Quick, V.; Spaccarotella, K.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. An Exploratory Study Examining Obesity Risk in Non-Obese Mothers of Young Children Using a Socioecological Approach. Nutrients 2018, 10, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, W. Eating disorders: Obesity, anorexia nervosa, and the person within. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1973, 225, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, S. Some extraordinary facts about obese humans and rats. Am. Psychol. 1971, 26, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polivy, J.; Herman, C.P. Dieting and binging. A causal analysis. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, M.; Telke, S.; Anderson, L.M.; Eisenberg, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Ethnic/racial and gender differences in disordered eating behavior prevalence trajectories among women and men from adolescence into adulthood. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 294, 114720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liechty, J.M.; Lee, M.J. Longitudinal predictors of dieting and disordered eating among young adults in the U.S. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F.; Barrada, J.R.; Roncero, M. Orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia as new eating styles. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrettini, S.; Caroli, A.; Torlone, E. Nutrition and Metabolic Adaptations in Physiological and Complicated Pregnancy: Focus on Obesity and Gestational Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 611929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.-L.; He, H.-L.; Wu, H.-Z. Analysis of the results of a survey on the impact of traditional “confinement in childbirth” customs on maternal health. Matern. Child Health Care China. 2008, 8, 1135–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, M.A.; Pinheiro, A.P.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Schmidt, M.I. Eating disorders symptoms in pregnancy and postpartum: A prospective study in a disadvantaged population in Brazil. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, R.; Meyer, D.; Galligan, R. Psychosocial factors, mental health symptoms, and disordered eating during pregnancy. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, S.; Fox, J.R.; Butterfield, C.; Stringer, E.; Furber, C. Treading the tightrope between motherhood and an eating disorder: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Haigh, E.A. Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Fernandez, I.D.; Groth, S.W. Mental Health, Behavior Change Skills, and Eating Behaviors in Postpartum Women. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 932–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- das Neves, M.C.; Teixeira, A.A.; Garcia, F.M.; Rennó, J.; da Silva, A.G.; Cantilino, A.; Rosa, C.E.; Mendes-Ribeiro, J.A.; Rocha, R.; Lobo, H.; et al. Eating disorders are associated with adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2022, 44, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.K.; Sonneville, K.R. Understanding suicide risk and eating disorders in college student populations: Results from a National Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.C.I.; Nagpal, T.S. The WOMBS Framework: A review and new theoretical model for investigating pregnancy-related weight stigma and its intergenerational implications. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.; Chan, F.; Prichard, I.; Coveney, J.; Ward, P.; Wilson, C. Intergenerational transmission of dietary behaviours: A qualitative study of Anglo-Australian, Chinese-Australian and Italian-Australian three-generation families. Appetite 2016, 103, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagl, M.; Hilbert, A.; de Zwaan, M.; Braehler, E.; Kersting, A. The German Version of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties, Measurement Invariance, and Population-Based Norms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrada, J.R.; van Strien, T.; Cebolla, A. Internal Structure and Measurement Invariance of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) in a (Nearly) Representative Dutch Community Sample. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2016, 24, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojorquez, I.; Bustos, J.; Valdez, V.; Unikel, C. Life course, sociocultural factors and disordered eating in adult Mexican women. Appetite 2018, 121, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J.A.; Hurley, K.M.; Caulfield, L.E.; Black, M.M. Maternal mental health symptoms are positively related to emotional and restrained eating attitudes in a statewide sample of mothers participating in a supplemental nutrition program for women, infants and young children. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.C.I.; Schetter, C.D.; Brewis, A.; Tomiyama, A.J. The psychological burden of baby weight: Pregnancy, weight stigma, and maternal health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 235, 112401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidstrup, H.; Brennan, L.; Kaufmann, L.; de la Piedad Garcia, X. Internalised weight stigma as a mediator of the relationship between experienced/perceived weight stigma and biopsychosocial outcomes: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Affuso, G.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Pizzini, B.; Zanfardino, A.; Iafusco, D. Prevalence of disordered eating behaviors in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Results of multicenter Italian nationwide study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1108–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdier, L.; Morvan, Y.; Kotbagi, G.; Kern, L.; Romo, L.; Berthoz, S. Examination of emotion-induced changes in eating: A latent profile analysis of the Emotional Appetite Questionnaire. Appetite 2018, 123, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y. Application of LPA in Mental Health Research. Adv. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Robinovich, J.; Orellana, L.; Miranda-Zapata, E.; Oda-Montecinos, C.; Hueche, C.; Lobos, G.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Lapo, M.; Silva, J.; et al. Eating styles profiles in Chilean women: A latent Profile analysis. Appetite 2021, 163, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hirschi, A.; Wang, M.; Valero, D.; Kauffeld, S. Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 120, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.Y.; Strong, C.; Latner, J.D.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.C.; Cheung, P. Mediated effects of eating disturbances in the association of perceived weight stigma and emotional distress. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, L.E.; Latner, J.D. Understanding self-directed stigma: Development of the weight bias internalization scale. Obesity 2008, 16 (Suppl. S2), S80–S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciupitu-Plath, C.; Wiegand, S.; Babitsch, B. The Weight Bias Internalization Scale for Youth: Validation of a Specific Tool for Assessing Internalized Weight Bias Among Treatment-Seeking German Adolescents With Overweight. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Tsai, M.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Strong, C.; Latner, J.D.; Fung, X.C.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Tsang, H.W.H. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of the Weight Self-Stigma Questionnaire and Weight Bias Internalization Scale in children and adolescents. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2019, 19, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.T.; Yip, S.K.; Chiu, H.F.; Leung, T.Y.; Chan, K.P.; Chau, I.O.; Leung, H.C.; Chung, T.K. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 172, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.; James Bateman, C.; Pearce-Dunbar, V.; Powell, M.; Harrison, A. Exploring the impact of BMI on body dissatisfaction and eating behaviors among Caribbean university women. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, D.D.; Mitchison, D.; Mannan, H.; Griffiths, S.; Appolinario, J.C.; da Veiga, G.V.; Touyz, S.; Hay, P. Twenty-year associations between disordered eating behaviors and sociodemographic features in a multiple cross-sectional sample. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 5012–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojcic, I.; Dong, X.; Ren, X. Body Image and Sociocultural Predictors of Body Image Dissatisfaction in Croatian and Chinese Women. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Chen, H. Risk factors for disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: Prospective evidence from mainland Chinese boys and girls. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011, 120, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Luo, Y.-j.; Chen, H. Body Image Victimization Experiences and Disordered Eating Behaviors among Chinese Female Adolescents: The Role of Body Dissatisfaction and Depression. Sex Roles 2020, 83, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijlholt, M.; Van Uytsel, H.; Ameye, L.; Devlieger, R.; Bogaerts, A. Eating behaviors in relation to gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippert, K.E.; Tomiyama, A.J.; Smieszek, S.M.; Incollingo Rodriguez, A.C. The Media as a Source of Weight Stigma for Pregnant and Postpartum Women. Obesity 2021, 29, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiu, M.; Yang, Y.; Yan, J.; Tang, K. Maternal postnatal confinement practices and postpartum depression in Chinese populations: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R. Which care? Whose responsibility? And why family? A Confucian account of long-term care for the elderly. J. Med. Philos. 2007, 32, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, O.; Hwang, K.K. Guilt and Shame in Chinese Culture: A Cross-cultural Framework from the Perspective of Morality and Identity. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2003, 33, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; O’Flynn, J.L.; Bourdeau, A.; Zimmerman, E. A biopsychosocial model of body image, disordered eating, and breastfeeding among postpartum women. Appetite 2018, 126, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, S.; Phipps, M.G.; Abrams, B.; Darroch, F.; Grantham, K.; Schaffner, A.; Wing, R.R. Does behavioral intervention in pregnancy reduce postpartum weight retention? Twelve-month outcomes of the Fit for Delivery randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, M.W.; McCabe, J.E. Postpartum Depression: Current Status and Future Directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Gau, M.L.; Cheng, S.F.; Chen, T.L.; Wu, C.J. Excessive gestational weight gain and emotional eating are positively associated with postpartum depressive symptoms among taiwanese women. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.S.; Latner, J.D.; Puhl, R.M.; Vartanian, L.R.; Giles, C.; Griva, K.; Carter, A. The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite 2016, 102, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, F.; Puhl, R.M.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Ryan, D.H.; Mechanick, J.I.; Nadglowski, J.; Ramos Salas, X.; Schauer, P.R.; Twenefour, D.; et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groshon, L.C.; Pearl, R.L. Longitudinal associations of binge eating with internalized weight stigma and eating self-efficacy. Eat. Behav. 2023, 50, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancu, A.S.; Diaconu-Gherasim, L.R. Weight stigma and mental health outcomes in early-adolescents. The mediating role of internalized weight bias and body esteem. Appetite 2024, 196, 107276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | N (%) | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | _ | _ | 30.92 (4.67) |

| Residence | Rural | 73 (14.4) | _ |

| Urban | 346 (68.2) | _ | |

| Suburb | 88 (17.4) | _ | |

| Education level | High school and below | 71 (14.0) | _ |

| University | 358 (70.6) | _ | |

| Postgraduate and above | 78 (15.4) | _ | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | <3000 | 44 (8.7) | _ |

| 3000~5000 | 119 (23.5) | _ | |

| >5000 | 344 (67.9) | _ | |

| Employment status | Unemployment | 59 (11.6) | _ |

| Incumbent | 327 (64.5) | _ | |

| Liberal profession | 121 (23.9) | _ | |

| Sleep condition | Poor | 104 (20.5) | _ |

| General | 242 (47.7) | _ | |

| Good | 126 (24.9) | _ | |

| Very good | 35 (6.9) | _ | |

| BMI | _ | _ | 22.94 (3.00) |

| PPWR | _ | _ | 4.72 (6.30) |

| PWSQ | _ | _ | 0.46 (1.23) |

| WBIS | _ | _ | 25.50 (9.26) |

| EPDS | _ | _ | 8.26 (5.91) |

| Emotional eating | _ | _ | 27.61 (10.89) |

| External eating | _ | _ | 29.93 (7.14) |

| Restrained eating | _ | _ | 24.07 (8.73) |

| Model | AIC | BIC | aBIC | PLMR | PBLRT | Entropy | Group Size for Each Profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| 1-Class | 10,936.015 | 10,961.386 | 10,942.341 | _ | _ | _ | 507 | ||||

| 2-Class | 10,799.329 | 10,841.614 | 10,809.873 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.854 | 48 | 459 | |||

| 3-Class | 10,698.627 | 10,757.826 | 10,713.388 | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.779 | 335 | 35 | 137 | ||

| 4-Class | 10,650.851 | 10,726.964 | 10,669.830 | 0.0045 | 0.0000 | 0.801 | 278 | 35 | 168 | 26 | |

| 5-Class | 10,578.324 | 10,671.351 | 10,601.520 | 0.0522 | 0.0000 | 0.879 | 37 | 163 | 170 | 111 | 26 |

| 3-Class | Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profile 1 | 0.921 | 0.008 | 0.061 |

| Profile 2 | 0.178 | 0.920 | 0.000 |

| Profile 3 | 0.145 | 0.000 | 0.853 |

| Variable | Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 | F/χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional eating (M ± SD) | 14.17 ± 2.80 | 22.06 ± 6.18 a | 40.93 ± 6.92 ab | 521.992 | <0.001 * |

| External eating (M ± SD) | 13.06 ± 3.63 | 30.00 ± 5.41 a | 34.07 ± 4.86 ab | 230.814 | <0.001 * |

| Restrained eating (M ± SD) | 14.54 ± 6.24 | 23.36 ± 8.08 a | 28.21 ± 8.45 ab | 43.658 | <0.001 * |

| Age (M ± SD) | 30.80 ± 5.42 | 30.82 ± 4.44 | 31.17 ± 5.01 | 0.275 | 0.760 |

| BMI (M ± SD) | 22.69 ± 2.73 | 22.58 ± 2.86 | 23.91 ± 3.19 ab | 10.109 | <0.001 * |

| PWSQ (M ± SD) | 0.31 ± 1.21 | 0.36 ± 1.07 | 0.74 ± 1.52 b | 5.209 | 0.006 * |

| WBIS (M ± SD) | 24.06 ± 9.63 | 24.21 ± 8.57 | 29.01 ± 9.91 ab | 14.240 | <0.001 * |

| EPDS (M ± SD) | 3.34 ± 3.97 | 7.96 ± 5.51 a | 10.26 ± 6.40 ab | 22.101 | <0.001 * |

| PPWR (M ± SD) | 7.47 ± 6.71 | 3.92 ± 6.10 a | 5.95 ±6.33 b | 8.885 | <0.001 * |

| Residence | 1.396 | 0.845 | |||

| Rural | 6 (17.1) | 51 (15.2) | 16 (11.7) | ||

| Urban | 24 (68.6) | 226 (67.5) | 96 (70.1) | ||

| Suburb | 5 (14.3) | 58 (17.3) | 25 (18.2) | ||

| Education level | 7.785 | 0.100 | |||

| High school and below | 6 (17.1) | 48 (14.3) | 17 (12.4) | ||

| University | 27 (77.1) | 241 (71.9) | 90 (65.7) | ||

| Postgraduate and above | 2 (5.7) | 46 (13.7) | 30 (21.9) | ||

| Monthly income (RMB) | 4.747 | 0.314 | |||

| <3000 | 5 (14.3) | 29 (8.7) | 10 (7.3) | ||

| 3000~5000 | 10 (28.6) | 83 (24.8) | 26 (19.0) | ||

| >5000 | 20 (57.1) | 223 (66.6) | 101 (73.7) | ||

| Employment status | 6.593 | 0.159 | |||

| Unemployment | 4 (11.4) | 36 (10.7) | 19 (13.9) | ||

| Incumbent | 17 (48.6) | 221 (66.0) | 89 (65.0) | ||

| Liberal profession | 14 (40.0) | 78 (23.3) | 29 (21.2) | ||

| Sleep condition | 15.116 | 0.019 * | |||

| Poor | 3 (8.6) | 60 (17.9) | 41 (29.9) ab | ||

| General | 18 (51.4) | 163 (48.7) | 61 (44.5) | ||

| Good | 13 (37.1) | 87 (26.0) | 26 (19.0) | ||

| Very good | 1 (2.9) | 25 (7.5) | 9 (6.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, J.; Xu, T.; Tan, X.; He, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Tang, J.; Sun, M. Eating Styles Profiles and Correlates in Chinese Postpartum Women: A Latent Profile Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142299

Peng J, Xu T, Tan X, He Y, Zeng Y, Tang J, Sun M. Eating Styles Profiles and Correlates in Chinese Postpartum Women: A Latent Profile Analysis. Nutrients. 2024; 16(14):2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142299

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Jiayuan, Tian Xu, Xiangmin Tan, Yuqing He, Yi Zeng, Jingfei Tang, and Mei Sun. 2024. "Eating Styles Profiles and Correlates in Chinese Postpartum Women: A Latent Profile Analysis" Nutrients 16, no. 14: 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142299

APA StylePeng, J., Xu, T., Tan, X., He, Y., Zeng, Y., Tang, J., & Sun, M. (2024). Eating Styles Profiles and Correlates in Chinese Postpartum Women: A Latent Profile Analysis. Nutrients, 16(14), 2299. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16142299