Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness

Abstract

1. Introduction

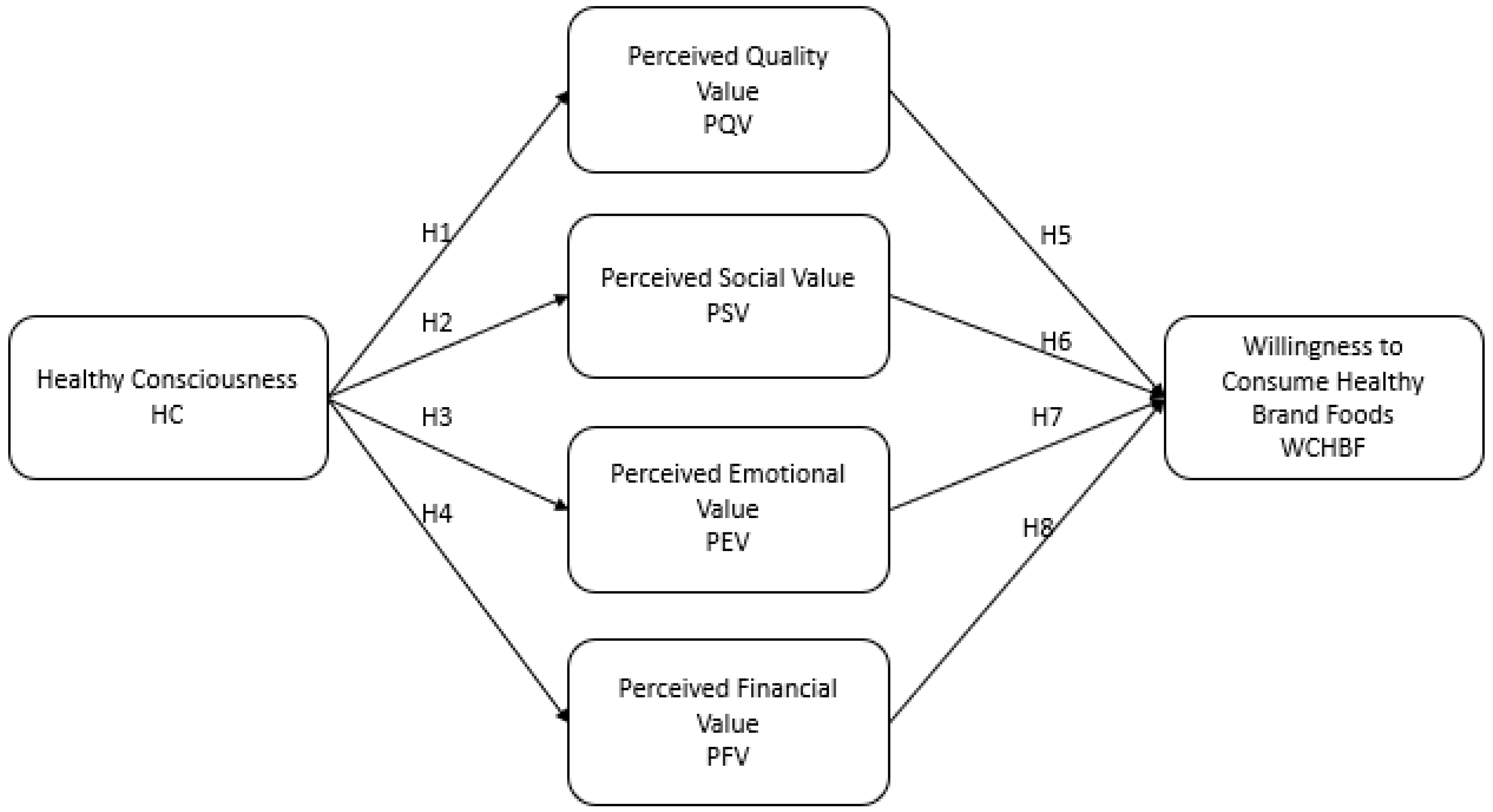

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measurement Scales

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

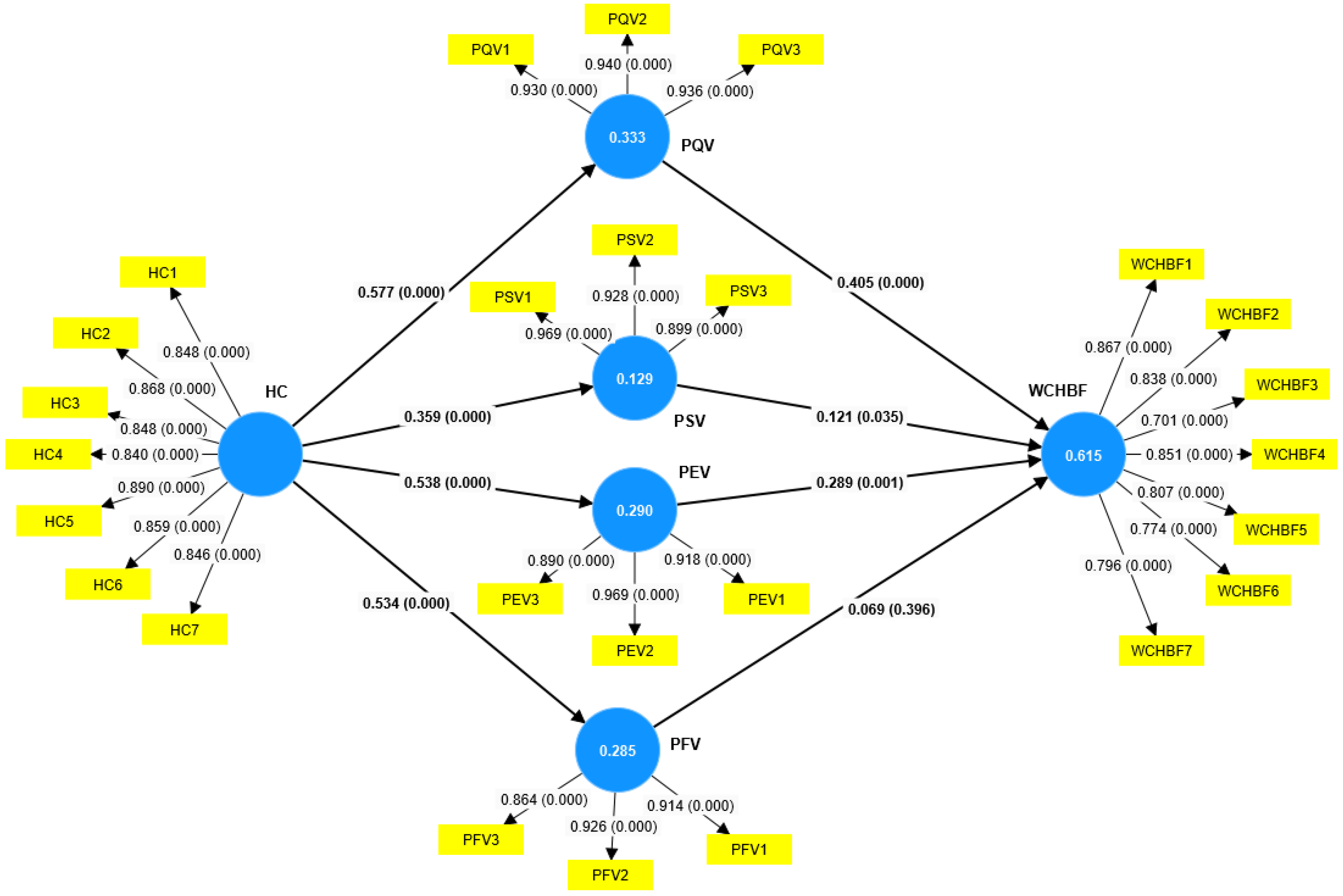

4.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy consciousness (HC) | Personally… | |

| HC1 | I reflect a lot on my health. | |

| HC2 | I am very conscious of my health. | |

| HC3 | I am alert to changes in my health. | |

| HC4 | I take responsibility for the state of my health. | |

| HC5 | I am aware of the state of my health throughout the day. | |

| HC6 | I look to choose foods that are good for my health. | |

| HC7 | I prefer food products without additives. | |

| Perceived quality value (PQV) | Union brand products… | |

| PQV1 | They are always of good quality. | |

| PQV2 | They have a good presentation. | |

| PQV3 | They have an adequate useful life. | |

| Perceived social value (PSV) | Consume Union brand products… | |

| PSV1 | It helps me feel accepted by others. | |

| PSV2 | Improves the way I am perceived. | |

| PSV3 | They give me social approval. | |

| Perceived emotional value (PEV) | Consume Union brand products… | |

| PEV1 | It gives me satisfaction. | |

| PEV2 | It makes me feel good. | |

| PEV3 | It gives me peace of mind. | |

| Perceived financial value (PFV) | Buy Union brand products… | |

| PFV1 | It offers good value for money. | |

| PFV2 | Worth the price. | |

| PFV3 | They have a reasonable price. | |

| Willingness to consume healthy brand food (WCHBF) | I am willing to buy the following Union brand products... | |

| WCHBF1 | Bread (multiseed, special whole wheat flour fortified with iron and B vitamins, bromate-free). | |

| WCHBF2 | Cookies (special whole wheat flour fortified with iron and B complex vitamins, free of artificial coloring). | |

| WCHBF3 | Beverages (0% alcohol wine, sugar-free fruit juices, free of artificial colors and flavorings). | |

| WCHBF4 | Granolas (mix of nuts, seeds, and cereals). | |

| WCHBF5 | Snacks (sticks with sesame, chia, kion, garlic, flaxseed, and omega 9, 6, and 3). | |

| WCHBF6 | Spreads (grape jam, peanut butter, and omega 6 and 9). | |

| WCHBF7 | Panettone (fortified with iron, contains source of fiber and source of protein, contains omega 6 and 9). |

References

- Fastame, M.C. Well-Being, Food Habits, and Lifestyle for Longevity. Preliminary Evidence from the Sardinian Centenarians and Long-Lived People of the Blue Zone. Psychol. Health Med. 2022, 27, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulain, M.; Herm, A.; Errigo, A.; Chrysohoou, C.; Legrand, R.; Passarino, G.; Stazi, M.A.; Voutekatis, K.G.; Gonos, E.S.; Franceschi, C.; et al. Specific Features of the Oldest Old from the Longevity Blue Zones in Ikaria and Sardinia. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 198, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, R.; Nuemi, G.; Poulain, M.; Manckoundia, P. Description of Lifestyle, Including Social Life, Diet and Physical Activity, of People = 90 Years Living in Ikaria, a Longevity Blue Zone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pes, G.M.; Dore, M.P.; Tsofliou, F.; Poulain, M. Diet and Longevity in the Blue Zones: A Set-and-Forget Issue? Maturitas 2022, 164, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitchcott, P.K.; Fastame, M.C.; Penna, M.P. More to Blue Zones than Long Life: Positive Psychological Characteristics. Health Risk Soc. 2018, 20, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyam, M.; Chuanmin, S.; Qasim, H.; Ihtisham, M.; Anjum, R.; Jiaxin, L.; Tikhomirova, A.; Khan, N. Food Consumption Behavior of Pakistani Students Living in China: The Role of Food Safety and Health Consciousness in the Wake of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 673771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxall, G.; Bhate, S. Cognitive Style and Personal Involvement as Explicators of Innovative Purchasing of ″Healthy″ Food Brands. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Millones-Liza, D.Y.; Esponda-Pérez, J.A.; Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Müller-Pérez, J.; Sánchez Díaz, L.C. Factors Influencing Loyalty to Health Food Brands: An Analysis from the Value Perceived by the Peruvian Consumer. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, A.M.; de Moura, A.P.; Deliza, R.; Cunha, L.M. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, E.; Bode, S. Positive Emotions and Their Upregulation Increase Willingness to Consume Healthy Foods. Appetite 2023, 181, 106420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byaruhanga, R.; Isgren, E. Rethinking the Alternatives: Food Sovereignty as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Food Security. Food Ethics 2023, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xue, Y.; Liu, T. Consumer Motivation for Organic Food Consumption: Health Consciousness or Herd Mentality. Front. Public. Health 2023, 10, 1042535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, Ş.G.; Kırcova, I. Using Theory of Consumption Values to Predict Organic Food Purchase Intention: Role of Health Consciousness and Eco-Friendly LOHAS Tendency. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 19, e0109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Bearth, A.; Hartmann, C. The Impacts of Diet-Related Health Consciousness, Food Disgust, Nutrition Knowledge, and the Big Five Personality Traits on Perceived Risks in the Food Domain. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, Y.D.; Deng, J.; Wang, C.L. Marketing Healthy Diets: The Impact of Health Consciousness on Chinese Consumers’ Food Choices. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.H.; Nguyen, D.N.; Nguyen, L.A.T. Quantitative Insights into Green Purchase Intentions: The Interplay of Health Consciousness, Altruism, and Sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2253616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yin, G.; Wan, X.; Guo, M.; Xie, Z.; Gu, J. Increasing Bike-Sharing Users’ Willingness to Pay—A Study of China Based on Perceived Value Theory and Structural Equation Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 747462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C.; Dong, C.-M. Exploring Consumers’ Purchase Intention on Energy-Efficient Home Appliances: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior, Perceived Value Theory, and Environmental Awareness. Energies 2023, 16, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Probst, T.M. The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Poorer: Country- and State-Level Income Inequality Moderates the Job Insecurity-Burnout Relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Kalinić, Z.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J. Assessing Determinants Influencing Continued Use of Live Streaming Services: An Extended Perceived Value Theory of Streaming Addiction. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L. Investment Intention towards Online Peer-to-Peer Platform: A Data Mining Approach Based on Perceived Value Theory. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 931, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, A.; Li, J.; Ke, Y.; Huo, S.; Ma, Y. Food and Nutrition Related Concerns Post Lockdown during Covid-19 Pandemic and Their Association with Dietary Behaviors. Foods 2021, 10, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauerné Gáthy, A.; Kovácsné Soltész, A.; Szűcs, I. Sustainable Consumption-Examining the Environmental and Health Awareness of Students at the University of Debrecen. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazdecki, M.; Goryńska-Goldmann, E.; Kiss, M.; Szakály, Z. Segmentation of Food Consumers Based on Their Sustainable Attitude. Energies 2021, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Sean Hyun, S.; Ali, M. Applying the Theory of Consumption Values to Explain Drivers’ Willingness to Pay for Biofuels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.; Newman, B.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez Abril, D.Y.; Calderón Sotero, J.H.; Padilla Delgado, L.M. Revisión de Literatura de La Teoría Del Comportamiento Planificado En La Decisión de Compra de Productos Orgánicos. Rev. Nac. Adm. 2021, 12, e3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Strong, D. Beyond Accuracy: What Data Quality Means to Data Consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1996, 12, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, C.; Zepeda, L. Lifestyle Segmentation of US Food Shoppers to Examine Organic and Local Food Consumption. Appetite 2011, 57, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerini, F.; Alfnes, F.; Schjøll, A. Organic- and Animal Welfare-labelled Eggs: Competing for the Same Consumers? J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 67, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andervazh, L.; Jalili, S.; Zanjani, S. Studying the Factors Affecting the Attitude and Intention of Buying Organic Food Consumers: Structural Equation Model. Iran. J. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wu, H.; Cheng, C.-C.; Ai, C.-H. What Drives Green Experiential Loyalty towards Green Restaurants? Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 1084–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihiro, Y.; Kuo, H.M.; Shieh, C.J. The Impact of Seniors’ Health Food Product Knowledge on the Perceived Value and Purchase Intention. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2019, 64, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Chua, J.Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X. The Determinants of Users’ Intention to Adopt Telehealth: Health Belief, Perceived Value and Self-Determination Perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antošová, I.; Stávková, J. Changes in the Intensity and Impact of Factors Influencing Consumer Behaviour in the Food Market over Time. Agric. Econ. 2023, 69, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A. Consumers’ Purchasing Decisions Regarding Environmentally Friendly Products: An Empirical Analysis of German Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, A.; Aljuaid, M.; Khan, Z.; Mahmood, Z.; Shahid, D. Role of Extrinsic Cues in the Formation of Quality Perceptions. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 913836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, J.; Su, W.; Li, G. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Intention: A Perspective of Ethical Decision Making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursan, R.; Wiryawan, D.; Jimad, H.; Listiana, I.; Riantini, M.; Yanfika, H.; Widyastuti, R.; Mutolib, A.; Adipathy, D. Effect of Consumer Skepticism on Consumer Intention in Purchasing Green Product. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1027, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do Mindfulness and Perceived Organizational Support Work? Fear of COVID-19 on Restaurant Frontline Employees’ Job Insecurity and Emotional Exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japutra, A.; Vidal-Branco, M.; Higueras-Castillo, E.; Molinillo, S. Unraveling the Mechanism to Develop Health Consciousness from Organic Food: A Cross-Comparison of Brazilian and Spanish Millennials. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Chen, C.-W.; Tung, Y.-C. Exploring the Consumer Behavior of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Belt and Road Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, M.; Ruiz, M.; Puiggròs, C. “How Long Is Its Life?”: Qualitative Analysis of the Knowledge, Perceptions and Uses of Fermented Foods among Young Adults Living in the City of Barcelona. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Humana Y Diet. 2021, 25, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, B.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Z.; Qiu, Y. The Relationship between Health Consciousness and Home-Based Exercise in China during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Law, R.; Heo, C. An Investigation of the Perceived Value of Shopping Tourism. J. Travel. Res. 2018, 57, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loor-Noboa, A.; Paez-Salguero, K.; Moreno-Gavilanes, K. Compras Impulsivas de Nuevos Productos: Un Análisis Empírico Del Sector Comercial de La Provincia de Tungurahua. 593 Digit. Publ. CEIT 2022, 7, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Lu, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Q. Exploring Tourists’ Intentions to Purchase Homogenous Souvenirs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadeikiene, A.; Svarcaite, A. Impact of Consumer Environmental Consciousness on Consumer Perceived Value from Sharing Economy. Eng. Econ. 2021, 32, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrozy, U.; Lawonk, K. The Multiple Dimensions of Consumption Values in Ecotourism. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, S.F.; Ahmad, G.N. Perceived Value of Green Residence: The Role of Perceived Newness and Perceived Relative Advantage. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2020, 8, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Shi, H.; Ye, W.; Wen, Z.; Li, R.; Xu, Y. Development and Validation of Nutrition Literacy Assessment Instrument for Chinese Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusva, A.; Dean, D.; Suhartanto, D.; Syarief, M.E.; Arifin, A.; Suhaeni, T.; Rafdinal, W. Loyalty Formation and Its Impact on Financial Performance of Islamic Banks—Evidence from Indonesia. J. Islam. Mark. 2020, 12, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermantoro, M. E-Servicescape Analysis and Its Effect on Perceived Value and Loyalty on e-Commerce Online Shopping Sites in Yogyakarta. Int. J. Bus. Ecosyst. Strategy (2687–2293) 2022, 4, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Pongsakornrungsilp, S.; Pongsakornrungsilp, P.; Jindabot, T.; Kumar, V. Why Do Customers Want to Buy COVID-19 Medicines? Evidence from Thai Citizens. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyhan, A. The Impact of Perception Related Social Media Marketing Applications on Consumers’ Brand Loyalty and Purchase Intention. EMAJ Emerg. Mark. J. 2019, 9, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Nava, L.; Egnell, M.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.; Córdova-Villalobos, J.; Barriguete-Meléndez, J.; Pettigrew, S.; Hercberg, S.; Julia, C.; Galán, P. Impacto de Diferentes Etiquetados Frontales de Alimentos Según Su Calidad Nutricional: Estudio Comparativo En México. Salud Publica Mex. 2019, 61, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Elsamen, A.A.; Akroush, M.N.; Asfour, N.A.; Al Jabali, H. Understanding Contextual Factors Affecting the Adoption of Energy-Efficient Household Products in Jordan. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P.; Castillo Apraiz, J.; Cepeda Carrión, G.A.; Roldán, J.L. Manual Avanzado de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); OmniaScience Scholar: Terrassa, Barcelona, 2019; ISBN 9788494799624. [Google Scholar]

- Orea-Giner, A.; Fusté-Forné, F. The Way We Live, the Way We Travel: Generation Z and Sustainable Consumption in Food Tourism Experiences. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Predanócyová, K.; Árvay, J.; Šnirc, M. Exploring Consumer Behavior and Preferences towards Edible Mushrooms in Slovakia. Foods 2023, 12, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otzen, T.; Manterola, C. Sampling Techniques on a Population Study. Int. J. Morphol. 2017, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Prakash, G.; Kumar, G. Does Environmentally Responsible Purchase Intention Matter for Consumers? A Predictive Sustainable Model Developed through an Empirical Study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.G. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Formula Modeling. Adv. Hosp. Leis. 1998, 8, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T.; Thomsen, T.U. The Influence of Consumers’ Interest in Healthy Eating, Definitions of Healthy Eating, and Personal Values on Perceived Dietary Quality. Food Policy 2018, 80, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Impact of Consumer Health Awareness on Dairy Product Purchase Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 14, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco-Solís, M.E.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Fernández-Ávalos, M.I.; Gómez-Vida, J.M.; Pérez-Iáñez, R.; Laynez-Rubio, C. Percepción Parental de Los Factores Relacionados Con La Obesidad y El Sobrepeso En Hijos/as Adolescentes: Un Estudio Cualitativo. Rev. Española Nutr. Humana Y Dietética 2022, 26, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, I.S.; Wulandari, R. The Effect of Price Perception and Product Quality on Consumer Purchase Interest with Attitude and Perceived Behavior Control as an Intervention Study on Environmentally Friendly Food Packaging (Foopak). Int. J. Sci. Manag. Stud. (IJSMS) 2023, 6, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Feijoo, M.; Bonisoli, L. Conocer Para Actuar: El Conocimiento y La Preocupación Como Antecedentes de La Intención de Compra de Productos Orgánicos. 593 Digit. Publ. CEIT 2022, 7, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, J.; Huang, W.; Tang, Y.; Man Li, R.Y.; Yue, X. Health-Driven Mechanism of Organic Food Consumption: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. Does Social Influence Turn Pessimistic Consumers Green? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2937–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, H.; Ali, S.; Danish, M.; Sulaiman, M. Factors Affecting Consumers Intentions to Purchase Dairy Products in Pakistan: A Cognitive Affective-Attitude Approach. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Luo, R. How Promotes Consumers’ Green Consumption of Eco-Friendly Packaged Food: Based on Value System. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.; Tan, C. Examining the Influence of Functional Value, Social Value and Emotional Value on Purchase Intention for Tires in Japan. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2024, 18, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, M.; Kim, Y.; Roh, T. Consumers’ Attention, Experience, and Action to Organic Consumption: The Moderating Role of Anticipated Pride and Moral Obligation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieria, A.; Raj, A.; De Almeida, M.; Lopes, E. How Cashback Strategies Yield Financial Benefits for Retailers: The Mediating Role of Consumers’ Program Loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzolari, G.; Denicolò, V. Loyalty Discounts and Price-Cost Tests. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2020, 73, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Al Asheq, A.; Ahmed, E.; Chowdhury, U.; Sufi, T.; Mostofa, M. The Intricate Relationships of Consumers’ Loyalty and Their Perceptions of Service Quality, Price and Satisfaction in Restaurant Service. TQM J. 2023, 35, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kaur, B. E-Mail Viral Marketing: Modeling the Determinants of Creation of “Viral Infection.”. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mookherjee, S.; Lee, J.; Sung, B. Multichannel Presence, Boon or Curse?: A Comparison in Price, Loyalty, Regret, and Disappointment. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, M.; Elisa, H.; Syarifuddin, S. The Growing Trend of Islamic Fashion: A Bibliometric Analysis. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2184557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradana, M.; Rubiyanti, N.; Marimon, F. Measuring Indonesian Young Consumers’ Halal Purchase Intention of Foreign-Branded Food Products. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez González, I.; Benítez Luzuriaga, F.; Moscoso Parra, A.; Muñoz Suarez, M. Desarrollo Sostenible En Las Mipymes de Ecuador y Su Impacto En El Consumidor. Cumbres 2020, 6, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonisoli, L.; Micolta Bagui, P.E. Teoría de Valores de Consumo: Granjas Sostenibles En Ecuador. Rev. Erud. 2022, 3, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corboș, R.; Bunea, O.; Triculescu, M.; Mișu, S. Which Values Matter Most to Romanian Consumers? Exploring the Impact of Green Attitudes and Communication on Buying Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballco, P.; de-Magistris, T.; Caputo, V. Consumer Preferences for Nutritional Claims: An Exploration of Attention and Choice Based on an Eye-Tracking Choice Experiment. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, A.O.; Kazemi, S.; Liebichová, M.; Sarraf, S.C.M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Consumers’ Associative Networks of Plant-Based Food Product Communications. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödiger, M.; Hamm, U. How Are Organic Food Prices Affecting Consumer Behaviour? A Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, J.; Paul, J. Consumer Behavior and Purchase Intention for Organic Food: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 38, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Phan, T.T.H.; Nguyen, N.T. Evaluating the Purchase Behaviour of Organic Food by Young Consumers in an Emerging Market Economy. J. Strateg. Mark. 2019, 27, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, A.; German, J.; Almario, A.; Vistan, J.; Galang, J.; Dantis, J.; Balboa, E. Consumer Behavior Analysis and Open Innovation on Actual Purchase from Online Live Selling: A Case Study in the Philippines. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, H. Research on Consumers’ Purchase Intention of Cultural and Creative Products—Metaphor Design Based on Traditional Cultural Symbols. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, E.; Tingey, B.; Ose, D. Train the Trainer: Improving Health Education for Children and Adolescents in Eswatini. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajeev, M.; Joshy, C. Exploring Perceptions and Health Awareness in Fish Consumption Across Coastal and Inland Kerala. Indian. J. Ext. Educ. 2024, 60, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, A.; Kudo, K.; Murashita, K.; Nakaji, S.; Igarashi, A. Reduction in All-Cause Medical and Caregiving Costs through Innovative Health Awareness Projects in a Rural Area in Japan: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhazmi, A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Linguistic Landscapes on Lifestyle, Health Awareness and Behavior. World J. Engl. Lang. 2024, 14, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 451 | 87.0 |

| 26–33 | 41 | 7.9 |

| 34–42 | 14 | 2.7 |

| 43–50 | 6 | 1.2 |

| 51–58 | 6 | 1.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 183 | 35.3 |

| Female | 335 | 64.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 30 | 5.8 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.4 |

| Single | 486 | 93.8 |

| Religion | ||

| Adventist | 444 | 85.7 |

| Catholic | 57 | 11 |

| Evangelical | 7 | 1.4 |

| Other | 10 | 1.9 |

| Academic formation | ||

| Secondary completed | 19 | 3.7 |

| Advanced technician | 4 | 0.8 |

| University (undergraduate) | 462 | 89.2 |

| University (postgraduate) | 33 | 6.3 |

| Family economic income | ||

| Up to 2 minimum salaries | 266 | 51.4 |

| From 3 to 4 minimum salaries | 131 | 25.3 |

| From 5 to 10 minimum salaries | 92 | 17.8 |

| From 11 to 20 minimum salaries | 19 | 3.6 |

| Greater than 20 minimum salaries | 10 | 1.9 |

| Predictor | Code | Outer Loadings | α | Composite Reliability (rho_a) | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy consciousness (HC) | HC1 | 0.833 | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.960 | 0.773 |

| HC2 | 0.893 | |||||

| HC3 | 0.896 | |||||

| HC4 | 0.907 | |||||

| HC5 | 0.897 | |||||

| HC6 | 0.870 | |||||

| HC7 | 0.781 | |||||

| Perceived emotional value (PEV) | PEV1 | 0.943 | 0.947 | 0.949 | 0.966 | 0.904 |

| PEV2 | 0.953 | |||||

| PEV3 | 0.925 | |||||

| Perceived financial value (PFV) | PFV1 | 0.891 | 0.929 | 0.930 | 0.955 | 0.875 |

| PFV2 | 0.929 | |||||

| PFV3 | 0.907 | |||||

| Perceived quality value (PQV) | PQV1 | 0.945 | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.971 | 0.917 |

| PQV2 | 0.920 | |||||

| PQV3 | 0.943 | |||||

| Perceived social value (PSV) | PSV1 | 0.963 | 0.952 | 0.953 | 0.969 | 0.912 |

| PSV2 | 0.953 | |||||

| PSV3 | 0.941 | |||||

| Willingness to consume healthy brand food (WCHBF) | WCHB1 | 0.800 | 0.929 | 0.931 | 0.943 | 0.701 |

| WCHB2 | 0.778 | |||||

| WCHB3 | 0.779 | |||||

| WCHB4 | 0.778 | |||||

| WCHB5 | 0.826 | |||||

| WCHB6 | 0.809 | |||||

| WCHB7 | 0.785 |

| HC | PEV | PFV | PQV | PSV | WCHB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | ||||||

| PEV | 0.538 | |||||

| PFV | 0.534 | 0.781 | ||||

| PQV | 0.578 | 0.742 | 0.754 | |||

| PSV | 0.359 | 0.646 | 0.612 | 0.455 | ||

| WCHB | 0.561 | 0.721 | 0.673 | 0.724 | 0.535 |

| H | Hypothesis | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HC -> PQV | 0.577 | 0.577 | 0.039 | 14.829 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2 | HC -> PSV | 0.359 | 0.360 | 0.049 | 7.312 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3 | HC -> PEV | 0.538 | 0.539 | 0.044 | 12.284 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4 | HC -> PFV | 0.534 | 0.534 | 0.042 | 12.673 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | PQV -> WCHB | 0.405 | 0.407 | 0.071 | 5.693 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6 | PSV -> WCHB | 0.121 | 0.122 | 0.057 | 2.114 | 0.035 | Accepted |

| H7 | PEV -> WCHB | 0.289 | 0.288 | 0.086 | 3.375 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H8 | PFV -> WCHB | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.082 | 0.848 | 0.396 | Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albornoz, R.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Millones-Liza, D.Y.; Villar-Guevara, M.; Toyohama-Pocco, G. Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16131995

Albornoz R, García-Salirrosas EE, Millones-Liza DY, Villar-Guevara M, Toyohama-Pocco G. Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness. Nutrients. 2024; 16(13):1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16131995

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbornoz, Roger, Elizabeth Emperatriz García-Salirrosas, Dany Yudet Millones-Liza, Miluska Villar-Guevara, and Gladys Toyohama-Pocco. 2024. "Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness" Nutrients 16, no. 13: 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16131995

APA StyleAlbornoz, R., García-Salirrosas, E. E., Millones-Liza, D. Y., Villar-Guevara, M., & Toyohama-Pocco, G. (2024). Using the Theory of Perceived Value to Determine the Willingness to Consume Foods from a Healthy Brand: The Role of Health Consciousness. Nutrients, 16(13), 1995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16131995