Saponin Esculeoside A and Aglycon Esculeogenin A from Ripe Tomatoes Inhibit Dendritic Cell Function by Attenuation of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. EsA and Esg-A Extraction

2.2. Animals

2.3. DC Generation from Murine Bone Marrow

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.5. Flow Cytometric Cell Surface Staining

2.6. ELISA Assay for Cytokine Production

2.7. Endocytosis Assay

2.8. Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction (MLR) Assay

2.9. Western Blotting

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

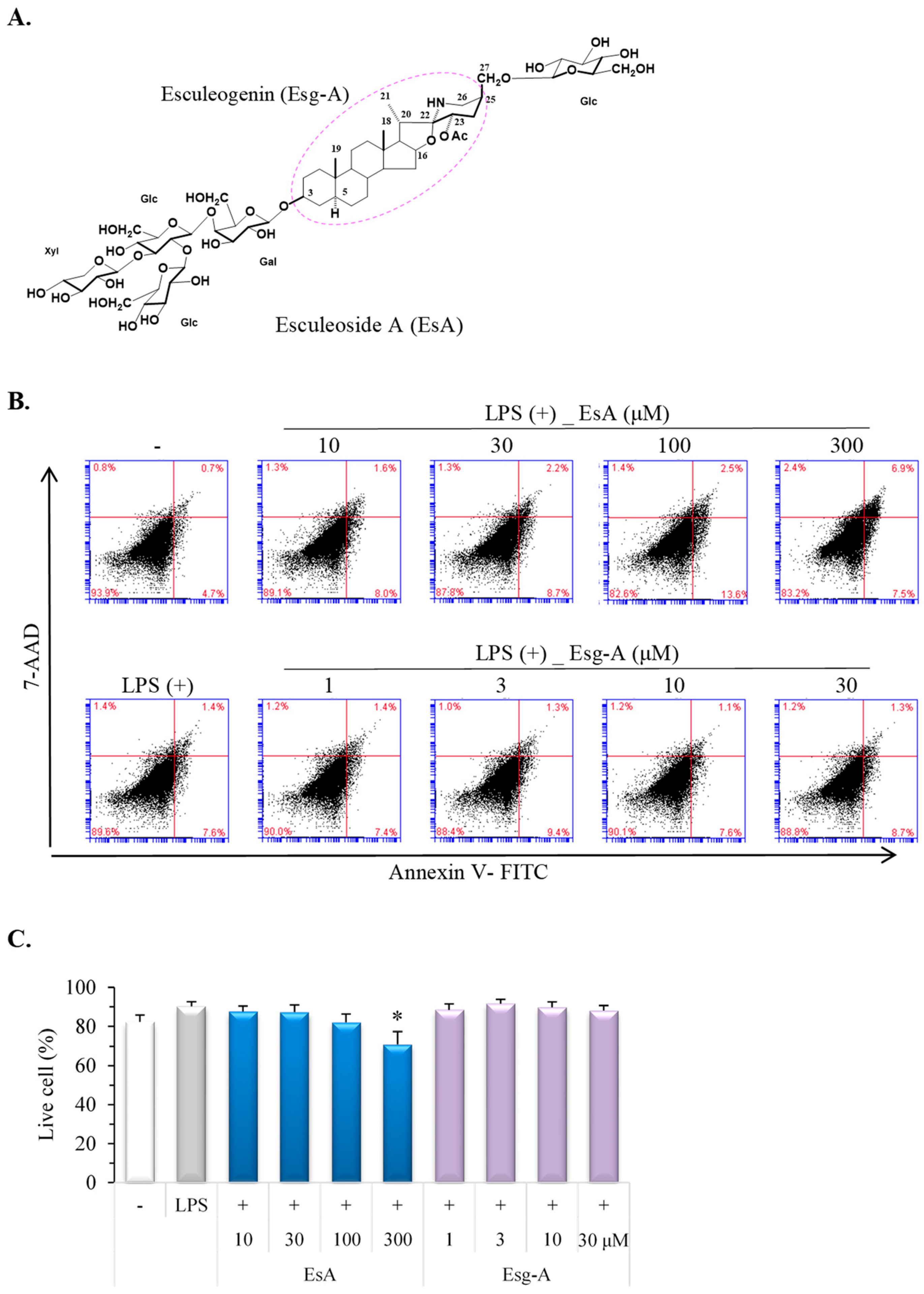

3.1. EsA/Esg-A Cytotoxicity in LPS-Treated Mature DCs

3.2. EsA/Esg-A Impair Phenotypic Maturation of DCs

3.3. EsA/Esg-A Inhibit LPS-Activated IL-12 and TNF-α Production by DCs

3.4. EsA/Esg-A Increase Endocytosis of Dextran-FITC in LPS-Activated DCs

3.5. EsA/Esg-A Decrease Allostimulatory Capacity of DCs

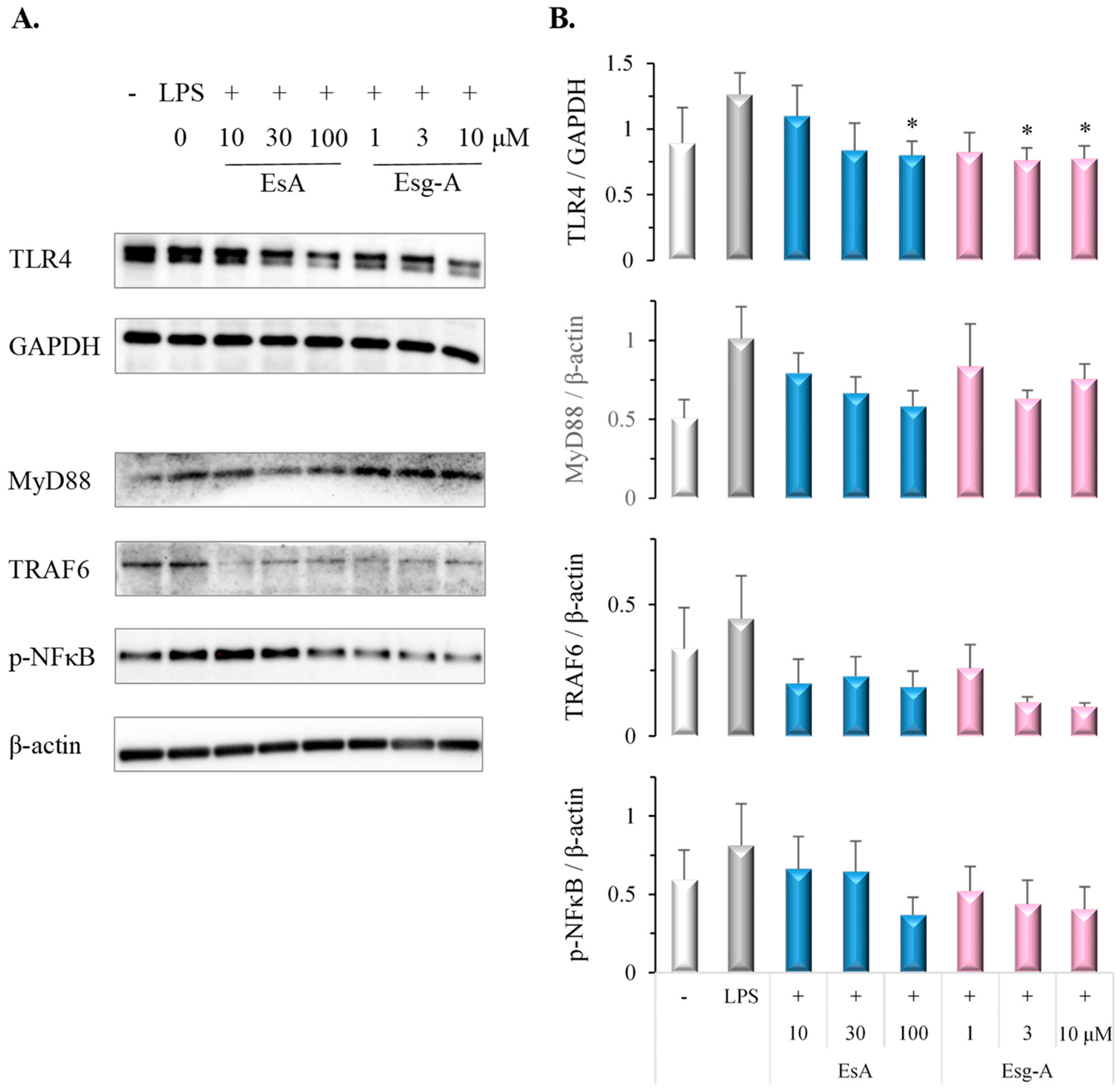

3.6. EsA/Esg-A Suppress the TLR4-MyD88-NFκB Pathway in LPS-Induced DC Maturation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilligan, K.L.; Ronchese, F. Antigen presentation by dendritic cells and their instruction of CD4+ T helper cell responses. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, S.; Eisenbarth, S.C. Dendritic Cell Regulation of T Helper Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 759–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, P.A.; Furuta, K. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoober, J.K.; Eggink, L.L.; Cote, R. Stories from the Dendritic Cell Guardhouse. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, B. Understanding the development of Th2 cell-driven allergic airway disease in early life. Front. Allergy 2023, 3, 1080153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.C.; Yeh, W.C.; Ohashi, P.S. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine 2008, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 Signaling Pathway Modulators as Potential Therapeutics in Inflammation and Sepsis. Vaccines 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faugaret, D.; Lemoine, R.; Baron, C.; Lebranchu, Y.; Velge-Rousselet, F. Mycophenolic acid differentially affects dendritic cell maturation induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lipopolysaccharide through a different modulation of MAPK signaling. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.C.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y. Tumor necrosis factor receptor- associated factor 6 (TRAF6) regulation of development, function, and homeostasis of the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2015, 266, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanarek, N.; Ben-Neriah, Y. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol. Rev. 2012, 246, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell 2008, 132, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, J.; Hawiger, D. Life and death of tolerogenic dendritic cells. Trends Immunol. 2023, 44, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passeri, L.; Marta, F.; Bassi, V.; Gregori, S. Tolerogenic Dendritic Cell-Based Approaches in Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackern-Oberti, J.P.; Llanos, C.; Vega, F.; Salazar-Onfray, F.; Riedel, C.A.; Bueno, S.M.; Kalergis, A.M. Role of dendritic cells in the initiation, progress and modulation of systemic autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015, 14, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, A.; Ju, X. Tolerogenic dendritic cells as a target for the therapy of immune thrombocytopenia. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2012, 18, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.; Ha, S.J. Generation of Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells and Their Therapeutic Applications. Immune Netw. 2016, 16, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Yahara, S.; Ikeda, T.; Ono, M.; Nohara, T. Cytotoxic major saponin from tomato fruits. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 234–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsumata, A.; Kimura, M.; Saigo, H.; Aburaya, K.; Nakano, M.; Ikeda, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Nagai, R. Changes in esculeoside A content in different regions of the tomato fruit during maturation and heat processing. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2011, 59, 4104–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.R.; Kanda, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Manabe, H.; Nohara, T.; Yokomizo, K. Anti- hyaluronidase Activity in Vitro and Amelioration of Mouse Experimental Dermatitis by Tomato Saponin, Esculeoside A. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.R.; Yamada, R.; Huruiti, E.; Kitahara, N.; Nakamura, H.; Fang, J.; Nohara, T.; Yokomizo, K. Ripe Tomato Saponin Esculeoside A and Sapogenol Esculeogenin A Suppress CD4+ T Lymphocyte Activation by Modulation of Th2/Th1/Treg Differentiation. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Suryawanshi, H.; Morozov, P.; Gay-Mimbrera, J.; Del Duca, E.; Kim, H.J.; Kameyama, N.; Estrada, Y.; Der, E.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis of human skin identifies novel fibroblast subpopulation and enrichment of immune subsets in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1615–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Takaki, A.; Uehara, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Okawa, M.; Nohara, T. Tomato steroidal alkaloid glycosides, esculeoside A and B., from ripe fruits. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 4915–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, J.S.; Park, Y.; Kang, J.S.; Hwang, B.Y.; Hong, J.T.; Kim, Y.; Han, S.B. Bisabolangelone inhibits dendritic cell functions by blocking MAPK and NF-κB signaling. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borriello, F.; Sethna, M.P.; Boyd, S.D.; Schweitzer, A.N.; Tivol, E.A.; Jacoby, D.; Strom, T.B.; Simpson, E.M.; Freeman, G.J.; Sharpe, A.H. B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity 1997, 6, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.; Waters, E.; Rowshanravan, B.; Hinze, C.; Williams, C.; Janman, D.; Fox, T.A.; Booth, C.; Pesenacker, A.M.; Halliday, N.; et al. Differences in CD80 and CD86 transendocytosis reveal CD86 as a key target for CTLA-4 immune regulation. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1365–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psarras, A.; Antanaviciute, A.; Alase, A.; Carr, I.; Wittmann, M.; Emery, P.; Tsokos, G.C.; Vital, E.M. TNF-alpha Regulates Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells by Suppressing IFN-alpha Production and Enhancing T Cell Activation. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozzani, S.; Del Prete, A.; Bosisio, D. Dendritic cell recruitment and activation in autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2017, 85, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimilli, S.; Johnson, J.B.; Alexander-Miller, M.A.; Parks, G.D. TLR-4 and -6 agonists reverse apoptosis and promote maturation of simian virus 5-infected human dendritic cells through NFκB-dependent pathways. Virology 2007, 365, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.-R.; Kinno, S.; Kaihara, K.; Sawai, M.; Ishida, T.; Takechi, S.; Fang, J.; Nohara, T.; Yokomizo, K. Saponin Esculeoside A and Aglycon Esculeogenin A from Ripe Tomatoes Inhibit Dendritic Cell Function by Attenuation of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111699

Zhou J-R, Kinno S, Kaihara K, Sawai M, Ishida T, Takechi S, Fang J, Nohara T, Yokomizo K. Saponin Esculeoside A and Aglycon Esculeogenin A from Ripe Tomatoes Inhibit Dendritic Cell Function by Attenuation of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111699

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jian-Rong, Shigenori Kinno, Kenta Kaihara, Madoka Sawai, Takumi Ishida, Shinji Takechi, Jun Fang, Toshihiro Nohara, and Kazumi Yokomizo. 2024. "Saponin Esculeoside A and Aglycon Esculeogenin A from Ripe Tomatoes Inhibit Dendritic Cell Function by Attenuation of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111699

APA StyleZhou, J.-R., Kinno, S., Kaihara, K., Sawai, M., Ishida, T., Takechi, S., Fang, J., Nohara, T., & Yokomizo, K. (2024). Saponin Esculeoside A and Aglycon Esculeogenin A from Ripe Tomatoes Inhibit Dendritic Cell Function by Attenuation of Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling. Nutrients, 16(11), 1699. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111699