Abstract

Long-term exposure to even slightly elevated plasma cholesterol levels significantly increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. The latest evidence recommends an improvement in plasma lipid levels, even in children who are not affected by severe hypercholesterolemia. The risk–benefit profile of pharmacological treatments in pediatric patients with moderate dyslipidemia is uncertain, and several cholesterol-lowering nutraceuticals have been recently tested. In this context, the available randomized clinical trials are small, short-term and mainly tested different types of fibers, plant sterols/stanols, standardized extracts of red yeast rice, polyunsaturated fatty acids, soy derivatives, and some probiotics. In children with dyslipidemia, nutraceuticals can improve lipid profile in the context of an adequate, well-balanced diet combined with regular physical activity. Of course, they should not be considered an alternative to conventional lipid-lowering drugs when necessary.

1. Introduction

Optimal low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and/or triglyceride plasma levels significantly protect against cardiovascular disease (CVD) development, and higher levels are associated with an increased risk [1,2]. The optimal values are defined based on age and ethnicity. Dyslipidemias are largely prevalent disorders of lipoprotein metabolism that can result in abnormal lipid and lipoprotein values. The prevalence of dyslipidaemias is increasing all over the world, even in Mediterranean countries where the diet should be qualitatively healthier. A recent Italian study showed a prevalence of suboptimal cholesterolemia (total cholesterol–TC > 170 mg/dL) in 78% of children and adolescents [3]. Recent studies suggest that long-term mild exposure during childhood to even a mild suboptimal LDL-C level is associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. International guidelines suggest screening children and adolescents for lipid levels, especially in families with dyslipidemia and/or atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) [4,5].

In a large Australian cohort, subjects who had incident non-high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (non-HDL-C) dyslipidemia from childhood to adulthood and those with persistent dyslipidemia had dramatic increased risks of cardiovascular events (Hazard Ratio 2.17 [95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.00–4.69] and Hazard Ratio 5.17 [95% CI 2.80–9.56], respectively), when compared with those whose non-HDL-C levels remained within the guideline-recommended range in childhood and adulthood. Then, participants who had high non-HDL-C in childhood but whose non-HDL-C levels were within the guideline-recommended range in adulthood did not have a significantly increased risk (Hazard Ratio 1.13 (95%CI 0.50–2.56)) [6].

Thus, improvements in physical activity and some dietary behaviors that ensure all necessary nutrients for adequate growth during childhood are advisable [7,8], although specific lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment is needed to manage secondary and severe genetic dyslipidemias [9,10]. Some nutraceuticals have clearly demonstrated cholesterol-lowering activity in adults. Experts recommend their utilization in managing individuals who have a low estimated risk of developing ASCVD, but who show an insufficient metabolic response to dietary changes. Additionally, nutraceuticals may be considered for some low-risk patients with statin-intolerance when combined with ezetimibe [11,12].

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS), the first step in the management of adult and pediatric patients with hypercholesterolemia is nutritional approach and life-style management, followed by drug therapy [5,13].

Functional foods or “nutraceuticals” have been used as adjunct treatment for adult patients, and are suggested for pediatric patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) [13].

Studies on cholesterol-lowering nutraceuticals in children and adolescents are relatively limited, as only a few short-term, randomized, controlled studies have been performed. These are mainly concerned with the administration of (soluble) fibers and plant sterols/stanols, whereas sporadic reports have tested the efficacy and tolerability of standardized red yeast rice extract, soy proteins, probiotics, and Omega-3 and Omrega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).

This review article aimed to critically summarize the scientific evidence supporting cholesterol-lowering dietary supplements and nutraceuticals in managing children and adolescents with dyslipidemia.

We focused on the most widely used nutraceuticals in dyslipidemia management, especially those that have shown evidence of modifying plasma levels of LDL-C and triglycerides. Additionally, we also examined the impact of these nutraceuticals on TC and HDL-C levels, to provide clinicians comprehensive objective information to guide their decision-making process.

2. Materials and Methods

A detailed literature search was performed in this narrative review on PubMed using the following keywords: “Children”, “Adolescent”, “Pediatric”, “Hypercholesterolemia”, “Hypertriglyceridemia”, “Dyslipidemia”, “Dietary supplement”, “Nutraceutical”, “Efficacy”, “Tolerability”, “Safety”, “Cholesterol-lowering” and “Lipid-lowering”. Preference was given to placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials. The collected articles underwent independent review by two authors. Inclusion criteria were established prior to article review, and were as follows: (i) all published scientific papers that describe dietary supplement, nutraceuticals and lipid-lowering agents in pediatric population; and (ii) high-quality systematic research, randomized control trials, study cohorts and cross-sectional studies that were published in English. We excluded studies that were not reported in English, and those that exclusively focused on adults (age ≥ 19 years).

Findings were classified by the main mechanisms of action (i.e., cholesterol absorption inhibitors from the bowel, LDL synthesis inhibition by the liver, and a mixed mechanism of action), and summarized in tables and figures. The review tables included nutraceutical, study type, study aim, participants, intervention, intolerance, compliance and observed effects.

3. Natural Cholesterol Absorption Inhibitors from the Bowel

Several natural compounds can interfere with cholesterol absorption, significantly improving cholesterolemia in children and adolescents.

3.1. Soluble Fibers

Fibers are edible parts of plants that pass through the small intestine relatively unchanged in humans, and include complex carbohydrates such as non-starch polysaccharides (pectins, gums, cellulose, hemicellulose, oat bran and wheat bran), oligosaccharides (inulin and fructooligosaccharides), and lignin (i.e., the non-carbohydrate fraction of the dietary fiber). Fibers intake is linked to positive health outcomes, including a lower risk of developing ASCVD and obesity [14]. Fibers naturally contained in cereals, vegetables and fruits (as part of a balanced dietary pattern) ameliorate the lipid profile in adults [15], and reduce concentrations of TC and Low Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol (LDL-C) by 5–15% and 9–22%, respectively [16,17]. These beneficial effects have led regulatory agencies to issue health claims for the intake of fibers [18], oat β-glucan and its LDL-C lowering effect or ASCVD risk reduction [19,20].

A large cohort study on 5873 Japanese children (10–11 years) highlighted the presence of an inverse association between the consumption of dietary fibers and plasma concentrations of TC, and the presence of overweight and obesity, confirming data from clinical trials in adults [21]. Although dietary fibers help maintain good health, their quantitative need in children has not been defined yet [22]. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines relate it to the need for calorie intake (12 g/1000 calories), while the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines relate it to weight or age [23]. Pediatric recommendations widely vary across countries, being also influenced by the available evidence [24]. In general practice, many pediatricians follow a formula that involves adding 5 g/day to the child’s age (for children older than 3 years) [25]. Even if this guideline is often considered when advocating for a Mediterranean diet or a diet rich in vegetables, it is seldom met in clinical practice.

Children living in Western countries typically consume fewer vegetables and fruits, contributing to a lower dietary fiber intake, high calorie dense food, and highly refined high-fat diet [26]. The consequences of such an incorrect dietary intake include metabolic changes and hyperlipidemia, which are sometimes associated with overweight/obesity. In this context, a positive effect of dietary fibers on blood lipids with monounsaturated FAs (MUFAs) was shown in children in the Healthy Start Preschool Study of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Diet [27].

Soluble fibers include psyllium (viscous and non-fermentable fiber), glucomannan, oat, pectin, and guar gum (viscous and fermentable fiber) and are commercially available as unprocessed fibers that can be added to food or used as flavored powders or capsules. Psyllium, derived from the seed husk of Plantago ovata, is one of the richest sources of soluble mucilaginous dietary fiber, acting as a gel-forming polysaccharide, similarly to pectin and guar gum [28]. Locust bean gum (that is, a galactomannan from the carob tree) is a white and odorless powder extracted from the endosperm of beans without a distinctive taste. Pectin is less viscous than other fibers, but similar in ash and more palatable [29]. Glucomannan, the main polysaccharide obtained from the Asian tuber Amorphophallus konjac, is a palatable, highly viscous soluble fiber. Its chemical structure consists of a mannose (8): glucose (5) ratio linked by b-glycosidic bonds. Glucomannan has the highest molecular weight and viscosity among all dietary fibers [30,31]. Oat seeds are also an important source of the viscous soluble fiber beta-glucan [32].

The ability of fibers to lower plasma lipids relies on their physicochemical properties and viscosity. Soluble fiber acts mainly to form viscous solutions that slow gastric emptying and reduce fat absorption, thereby modulating lipoprotein metabolism. In the small intestine, the gelling process binds to dietary fats and hinders the absorption of cholesterol, and the reabsorption of bile acids increases their excretion in feces. It follows that there is a reduced uptake of intestinal cholesterol and a reduced circulation of chylomicrons. Of consequence is that the synthesis of bile in the liver increases and LDL-C levels decrease. Another cholesterol-lowering mechanism involves bacterial fermentation in the colon (except for lignin), which leads to production of short-chain FAs (acetate, propionate, and butyrate). Propionate inhibits cholesterol synthesis [33,34].

A relatively small number of short-term randomized clinical trials have investigated the cholesterol-lowering effect of fibers in children and adolescents with largely variable results, ranging from no effect to a 30% reduction in LDL-C plasma levels. The most frequently studied fiber is psyllium, followed by glucomannan, oats, and gum, which are usually added to STEP I (daily fat intake < 30%, saturated FAs < 10%, cholesterol < 300 mg) or STEP II (saturated FAs 7%, cholesterol < 200 mg), now indicated as CHILD I and CHILD II diet [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] (Table 1).

Balancing the fiber intake from food and nutraceuticals or fiber-added food is relevant to compliance and outcomes. A very restricted diet—as required by the STEP II diet—even if safe, is not always well accepted by children [43,44]. Combining the STEP I diet with food-enriched or capsule-containing fiber is often more effective in reducing LDL-C levels.

Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of psyllium [45,46]. A 12-week randomized controlled study on 50 children with mild hypercholesterolemia on a STEP I diet supplemented with psyllium (3.2 g/daily) showed an additional 8.9% LDL-C decrease compared with the controls [40]. Further, in 36 children with familial combined hyperlipoproteinemia, supplementation with psyllium (2.5–10 g, depending on the age) to a STEP I diet led to a TC and LDL-C level reduction of 11.9% and 13.8%, respectively [34]. Psyllium supplementation also improved the LDL-C lowering effect of the STEP II diet in children with hyperlipidemia [41], different from what was previously observed in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over study employing 6 g/day of psyllium in 20 children with mild hypercholesterolemia, already on the STEP II diet [36].

Glucomannan supplementation was successfully tested in 36 children with hyperlipidemia who underwent a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial that lasted 24 weeks. This cohort, affected by primary dyslipidemia, was fed a CHILD I diet for ≥1 month. Capsules containing glucomannan (500 mg) were administered at a dose of 1000–1500 mg/day depending on the proband’s weight. TC, LDL-C, and non-HDL-C levels decreased significantly by 5.1%, 7.3%, and 7.2%, respectively [47]. Consistent with previous findings, these results were more pronounced in females than males [41]. However, two meta-analyses of the LDL-C-lowering effect of glucomannan supplementation in children did not confirm any positive effect of this fiber on LDL-C levels [48,49].

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the available clinical studies testing the cholesterol-lowering effects of different fiber types in children.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the available clinical studies testing the cholesterol-lowering effects of different fiber types in children.

| Nutraceuticals | Type of Study [Reference] | Primary Aim of the Study | Participants | Main Inclusion Criteria of the Study | Intervention | Follow-Up | Intolerance and/or Side Effects | Compliance | Main Effects of the Tested Nutraceutical on LDL-C | Main Effects of the Tested Nutraceutical on Other Lipid Fractions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSYLLIUM | Randomized, double-blind, crossover, controlled clinical trial [35] | To assess the LDL-C lowering effect of psyllium-enriched breakfast cereal in children with hyperlipidemia | N. 32 children (6–18 years) | LDL-C > 90th percentile for age and sex at baseline | 58 g of a psyllium-enriched cereal/day for a total daily dose of 6.4 g soluble fiber from psyllium or placebo without psyllium | 6 weeks | N. 1 child experienced gastrointestinal effects with slight abdominal bloating | Good compliance |

|

|

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial [41] | To assess the LDL-C-lowering effect of psyllium in children with hypercholesterolemia | N. 20 children (5–17 years) | LDL-C > 110 mg/dL after ≥3 months of a controlled diet | 6 g/day ready-to-eat cereals with water-soluble psyllium fiber or placebo without psyllium | 4–5 weeks | No side effects | Good compliance (80%) |

|

| |

| Randomized, clinical trial [50] | To assess the TC and LDL-C lowering effect of psyllium in children | N. 36 children (3–17 years) | Children with primary type IIa hypercholesterolemia |

| 8 ± 2.4 months | No side effects | Good compliance |

|

| |

| Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial [45] | To assess the TC and LDL-C lowering effect of psyllium in children | N. 50 children (2–11 years) | LDL-C ≥ 110 mg/dL | Psyllium-enriched cereal containing 3.2 g of soluble fiber, each box of placebo cereal containing < 0.5 g of soluble fiber | 12 weeks | No side effects | Good Compliance |

|

| |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial [46] | To assess the LDL-C lowering effect of psyllium in Brazilian children and adolescents with mild-to-moderate dyslipidemia | N. 49 children (6–19 years) | TC > 4.40 mmol/L | 7.0 g/day psyllium or 7.0 g/day cellulose (placebo) | 8 weeks | No side effects | N. 2 children in the control group were excluded during follow up |

|

| |

| GUM | Randomized, crossover, controlled clinical trial [29] | To assess the LDL-C lowering effect of locust bean gum | N. 17 adults and N. 11 children (N. 18 participants with FCH + N. 10 controls) (Adults: 22–53 years; children: 10–18 years) |

|

| No side effects | Good compliance in adults |

|

| |

| GLUCOMANNAN | Randomized, double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled clinical trial [47] | To assess the efficacy and tolerability of dietary supplementation with glucomannan in children | N. 36 children (6–15 years) | TC levels higher than the age- and sex-specific 90th percentile | 2/week capsule containing either 500 mg of glucomannan or placebo | 8 weeks | No side effects | Good compliance (92% compliance for the dietary supplement and 90% compliance for the placebo) |

|

|

| PECTIN | Non randomized, controlled clinical trial [36] | To assess the efficacy of wheat bran and pectin mix on plasma lipids in children | N. 51 children (4–18 years) with high LDL-C and N. 33 controls (5–16 years) | LDL-C serum levels > 135 mg/dL after 6 months of dietary counselling (for the actively treated group) | Dietary counselling and dietary supplementation with 50% wheat bran + 50% of pectin, 2–3 tablets/day (50 mg × Kg/day) | 3 months | N. 2 children experienced abdominal discomfort and soft stools | Good compliance |

|

|

| GLUCOMANNAN + POLICOSANOLS OR CHROMIUM POLYNICOTINATE | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial [51] | To assess the effect of low-dose chromium-polynicotinate (Group A) or policosanols (Group B), and their glucomannan combination (Group C and Group D, respectively) in children | N. 120 children (3–16 years; Male, N. 60–Female: N. 60) |

|

capsules each at lunch and dinner; children > 6 years: 3 capsules each at lunch and dinner | 8 weeks | No side effects |

|

|

|

↑, Increase; ↓, decrease; Apo-B, apolipoprotein B; Apo-A1, apolipoprotein A1, HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; FH, familial hypercholesterolemia; FCH, familial combined hyperlipidemia; N., number.

Among other fibers, oat bran supplementation has been tested in children in several clinical trials [52]. For instance, oat bran significantly increased HDL-C levels and reduced LDL-C levels after 7 months of consumption (dosage: 1 g/kg body weight/day) compared with soy derivatives in 20 children with hypercholesterolemia (5–12 years) [53].

Furthermore, locust bean gum (Carruba) showed a significant 11–19% LDL-C level decrease when comparing active and placebo groups in a 16-week cross-over controlled trial, including 11 children with familial combined hyperlipidemia, 10 controls, and 17 adults who consumed locust bean gum (8–30 g/daily) [54].

Among these interventions (Table 1), psyllium consistently showed the highest reduction in LDL-C levels, ranging from 6.8% to 23%. This was followed by gum interventions, which resulted in a reduction of LDL-C levels ranging from 11% to 19%. Pectin interventions demonstrated a significant reduction of 17% in LDL-C levels. Lastly, Glucomannan interventions combined with Chromium polynicotinate or policosanols showed moderate reductions, ranging from 7.3% to 16% in LDL-C levels. It is important to note that these interventions were effective in lowering LDL-C levels in pediatric populations, but the extent of reduction varied across studies. The compliance was overall good, even if some children refused to follow the prescribed diet or take the capsules.

Even if a fiber rich diet is always to be preferred, when the intake is not sufficient, supplemented fibers are usually safe and well tolerated. Mild intestinal discomfort has been reported in clinical trials.

3.2. Plant Sterols

Plant sterols, also known as phytosterols or non-cholesterol sterols, are natural compounds found in plants, and are commonly consumed through foods like vegetable oils and nuts. These compounds are ingested in amounts comparable to cholesterol intake (200–400 mg/day), which cannot be synthesized by the human body. Plant sterols effectively and safely lower serum cholesterol levels by hindering cholesterol absorption [55]. Since 2001, plant sterol-enriched foods have been recommended by the National Cholesterol Education Program Guidelines as part of dietary strategies to reduce LDL-C levels [56].

Non-cholesterol sterols, or stanols (in the form of sterol esters), are available commercially, and are added to various foods such as bread, cereals, salad dressings, milk, margarine, and yogurt, often with different flavors and a good taste [57]. Studies have shown that, in adults, incorporating stanols into the milk matrix yielded better results compared to cereals, with LDL-C levels decreasing by 15.9% versus 5.4%, respectively [58]. While stanols were more effective in reducing cholesterol levels compared to sterols, most studies administered sterols at varying doses ranging from 1.6 to 2 g daily.

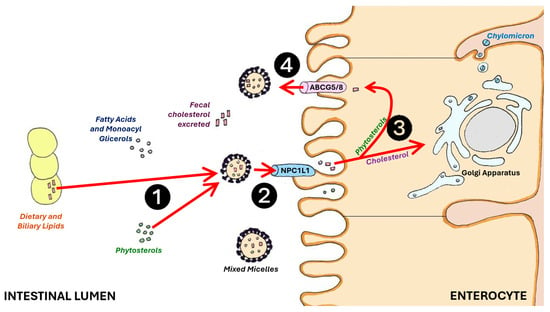

Plant sterols work by inhibiting cholesterol absorption in the intestines, leading to a reduction in serum cholesterol concentration [59]. Phytosterols, particularly sitostanol, compete with cholesterol for absorption in the intestines and displace cholesterol from micelles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phytosterols (❶) compete with cholesterol absorption at the intestinal brush border membrane by reversibly binding the NPC1L1 protein (❷). Free phytosterols (❸) are excreted into the intestinal lumen by ABCG5/8 in the intestinal cells (❹), and enhance cholesterol and bile salts excretion with feces (red arrows). ABCG5/8: adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette transporter G5/8; NPC1L1: Niemann–Pick C1-Like 1.

Phytosterols are more hydrophobic than cholesterol, making them more susceptible to mixed micelles. Cholesterol and phytosterols rely on Niemann–Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) protein for absorption into enterocytes. Once absorbed, non-esterified cholesterol and phytosterols are transported back into the intestinal lumen through the action of the ABCG5/G8 gene. Approximately 50% of the cholesterol, but less than 5% of plant sterols, is ultimately absorbed [60,61]. Phytosterols, when in their free form, are absorbed at low rates (less than 10%), while stanols are not absorbed physiologically [62]. The reduced uptake of intestinal cholesterol and its transport via chylomicrons to the liver result in decreased levels of intermediate-density lipoproteins in addition to LDL-C [63].

In several randomized clinical trials, plant sterols significantly decreased cholesterolemia in children with mild hypercholesterolemia and FH [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the randomized controlled trials testing the cholesterol-lowering effect of different types of phytosterols/stanols in children.

Dietary supplementation with 1.2–2.0 g/day sterols has been mainly tested in children with FH who had already been on STEP I or II, showing a further LDL-C lowering effect of ~10% in 2–12 months [63,65,67]. In children with FH, a daily intake of 2.3 g phytosterols significantly decreased TC (−11%) and LDL-C (−14%) levels compared with placebo spread [69], whereas higher decreases were observed in children undergoing stanol-added diet (3 g/day) [63]. Apolipoprotein B (Apo-B) levels were also significantly reduced by plant sterols (7–10%) [63,65,69]. The efficacy of phytosterols was further demonstrated in non-FH children on a STEP II diet and with mild hypercholesterolemia (mean TC > 197 mg and LDL-C > 125 mg/dL). The daily intake of 1.2 g plant sterol in two doses reduced TC (from −7% to −11%) and LDL-C (from −9% to −14%) levels, respectively, compared with the control group [64].

Margarine containing 1.6 g/day plant sterols or plant stanol ester reduced TC (−9%) and LDL-C (−12%) in children with FH after for 5–6 weeks [66,68], while in the STRIP study, 6-year-olds with mild hypercholesterolemia significantly decreased TC and LDL-C, respectively, by −5.4% and −7.5% [60]. Then, plant sterol supplementation could safely reduce LDL-C by roughly 10% and without significantly affecting other lipoprotein levels [73]. Remarkably, the Apo E4 or E3 genotypes were not reported to influence the biochemical effects of sterol addiction in children [65]. The administration of milk, yogurt and margarine frequently could influence the cholesterol-lowering effect of phytosterols [57,74], whereas the lipid drop seems independent of baseline levels, being the maximum effect usually reached in a short time (2 weeks, usually) [75].

An additive benefit of the above-mentioned changes is the significant decrease in small dense LDL-C levels after the daily dietary supplementation of 2 g plant sterols in children and adolescents with dyslipidemia [68]. It must, however, be recognized that TG and HDL-C concentrations in plasma are usually unaffected by phytosterol supplementation [76,77], as well as the endothelial function [72].

Children undergoing statin therapy show homeostatic changes characterized by increased cholesterol absorption and plant sterol levels. Phytosterol supplementation reverses these changes, and should be considered advantageous [78,79].

Phytosterols are usually safe and well-tolerated. Variations in carotenoids and fat-soluble vitamins have been reported by studies that used plant sterol- or stanol ester-enriched spreads in adults and children. In children with FH, lipid-adjusted lycopene levels decreased by 8.1% (p = 0.015) during the stanol period; however, this reduction was not significant at the 6-month follow-up. In addition, alfa- and beta-carotene levels significantly decreased by 17.4% and 10.9%, respectively, in children with FH after the daily consumption of 1.2 g plant sterols for 2 months, recovering at the 6-month follow-up [64]. In the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project for children (STRIP study), the dietary supplementation of 1.5 g phytosterols in children with mild hypercholesterolemia was associated to a decrease (−19%; p = 0.003) in serum beta-carotene to LDL-C ratio, while the alpha-tocopherol to LDL-C ratio remained unchanged [60]. Moreover, no changes were observed in the levels of the other carotenoids or fat-soluble vitamins [66]. To the extent that there is little data, improving vegetables and fruits intake in children should be suggested as add-on to phytosterol-added dietary regimen, to compensate for any possible reduction in carotenoid also related to seasonal dietary variations.

Long-term safety was questioned as phytosterol plasma levels increased the incidence of atherosclerosis [80], and should be related to an increased risk of cardiovascular events, as described in the large epidemiological cohorts of the PROCAM and MONICA/KORA studies [81,82]. Premature atherosclerosis has also been observed in the rare autosomal recessive familial form of sitosterolemia [83]. However, campesterol and sitosterol under physiological conditions do not exceed 1% of the total serum sterols, whereas cholesterol accounts for >99% of serum sterols. Moreover, lathosterol was not modified over a 12-week period, proving that the inhibition of cholesterol absorption by phytosterols does not cause an increased cholesterol synthesis [70].

3.3. Probiotics

Probiotics have a limited evidence of cholesterol-lowering effects in adults. This effect results from cholesterol absorption and bile salts hydrolysis (BSH) [84,85]. The first mechanism, activated by lactic acid bacteria, suppresses the reabsorption of cholesterol in the intestines, while the second mechanism affects the balance of bile salts, resulting in a decrease in plasma LDL-C levels. Moreover, certain strains of bifidobacteria improve blood lipid levels by converting linoleic acid (LA) into conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) [86].

A recent umbrella systematic review of 38 meta-analyses concluded that the probiotics supplementation was effective in reducing TC (effect size [ES], −0.46 mg/dL; 95%CI, −0.61, −0.30; p < 0.001), TG (ES, −0.13 mg/dL; 95%CI, −0.23, −0.04; p = 0.006), and LDL-C levels (ES, −0.29 mg/dL; 95%CI, −0.40, −0.19; p < 0.001), without affecting HDL-C [87] The evidence in children is rare. A 32-week-long, double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial was conducted involving children whose TC levels exceeded the 90th percentile for their age and sex. Administering a mixture of three bifidobacterium strains, selected for characteristics that ameliorated the lipid profile, such as BSH activity, cholesterol adsorption, and CLA production, mildly but significantly improved TC (3.4%), LDL-C (3.8%), and TG (1.9%) levels, and increased HDL-C (1.7%) levels [88]. The effect seems less impressive than that in adults; however, the effect could depend on the tested probiotic formulation, as the probiotic action depends on the strain, strain mix, dosage, and administration medium. Probiotic supplementation is usually safe [89] and well-tolerated. The available clinical data regarding probiotics in adults is inconclusive, and there is limited information available regarding their effects in children. Therefore, it would be premature to definitively state that probiotics have a significant lipid-lowering effect, given the limited evidence available.

4. Cholesterol-Lowering Dietary Components, and Nutraceuticals Acting through Different Mechanisms

Other dietary and food components with cholesterol-lowering actions beyond inhibiting cholesterol absorption from the bowel have also been tested in children and/or adolescents. These trials were usually small, short-term, and limited to specific settings (Table 3), suggesting the need for further confirming larger and long-term studies.

Table 3.

Main characteristics of randomized controlled trials testing the cholesterol-lowering effect of other nutraceuticals in children.

4.1. Nuts

Nuts (i.e., almonds, hazelnuts, pistachios, walnuts, macadamia nuts and peanuts) are classified as dry fruits. In recent decades, the cardioprotective and health-promoting qualities of nuts—particularly walnuts—have been extensively demonstrated in epidemiological studies. These positive effects are due to their composition rich in bioactives, such as monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), tocopherols (vitamin E), antioxidants, phytosterols, fibers and polyphenols, with hazelnuts being especially noteworthy in this regard [97]. Additionally, hazelnuts stand out for having the highest content of MUFAs among all nuts [98]. Regular hazelnut intake also seems to improve microbiota composition and reduce the intestinal concentration of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [96]. Moreover, polyphenols influence cholesterol absorption, TG synthesis and secretion and exert antioxidant effects [99].

To the best of our knowledge, only a few small trials until now have investigated the effects of hazelnuts on plasma lipids in children. Hazelnuts peeled or with the skin (0.43 g/kg of body weight, 15–30 g portions) were shown to significantly reduce LDL-C, while the ratio HDL-C/LDL-C increased compared to a control group receiving the STEP I diet. Moreover, their intake increased the MUFA/saturated fatty acids (SFA) ratio in red blood cells and lowered the endogenous and oxidative induced DNA damage [98].

4.2. Soy

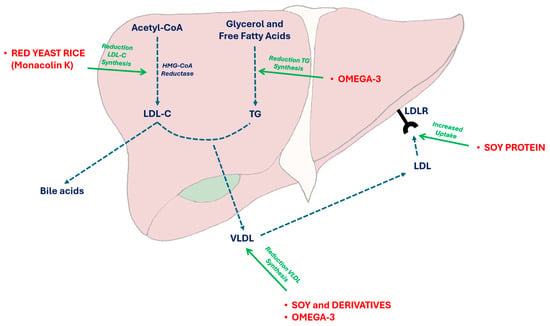

Soy contains several bioactive compounds that are supposed to improve plasma lipid levels in humans (i.e., isoflavones, phytosterols and specific peptides, which can promote LDL-C receptor expression in liver cells) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of some nutraceuticals on triglyceride and cholesterol synthesis. VLDL liver secretion and LDL uptake. In particular, red yeast rice is able to reversibly inhibit the HMGCoA reductase activity, while soy proteins main act by increasing the LDL-C receptor on liver cell surface and Omega 3 PUFAs by inhibiting the Apolipoprotein CIII and the lipoprotein-lipase activity. Acetyl-CoA: acetyl-coenzyme A; HMGCoA: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDLR: low-density lipoprotein receptor; TG: triglycerides; VLDL: very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

A recent meta-analysis showed that a median intake of 25 g/day of soy proteins during a median follow-up of 6 weeks decreased LDL-C plasma levels by 3–4% in adults (−4.8 mg/dL; 95%CI −6.7, −2.8 mg/dL, p < 0.0001) [95]. However, only few studies involving children exist. In a pilot study testing the cholesterol-lowering effect of soy or milk protein in children with FH, TC and LDL-C levels did not significantly change though TG and HDL-C improved [91]. Different results were obtained in a prospective study conducted on 16 children with FH. TC, LDL-C, and ApoB significantly improved (−7.7%, −6.4% and −12.6%, respectively) after a 3-month period in which soy proteins were incorporated into the Step I diet, being administered in the form of soy-based dairy-free milk at a dosage of 0.25–0.5 g/kg body weight [92]. This study represents an extended examination of soy protein in pediatric populations. Interestingly, even if children were generally adherent to the program, not all participants (4 out of 16) exhibited the desired response, despite having similar characteristics at entry. Overall, most studies concur on the efficacy of soy protein; however, safety concerns—such as allergic reactions or the potential effects of dietary phytoestrogens (i.e., isoflavones)—remain debatable, especially in the youngest participants [100]. A 13-week randomized controlled clinical trial has been recently launched to address the effect of a soy-rich diet compared to a low-fat diet and a control diet in children with FH. After 7 weeks from randomization, the reduction in LDL-C levels was notably greater in the soy group (155 ± 29 mg/dL) compared to the control group (176 ± 28 mg/dL; P for comparison = 0.038), with a similar trend observed at 13-week follow-up (LDL-C = 180 ± 42 mg/dL in the control group and 155 ± 30 mg/dL in the soy group; P for comparison = 0.089). The relative decrease in LDL-C levels was significantly associated with plasma isoflavone concentrations (specifically daidzein and genistein), as measured at week 7 [101]. Moreover, it must be acknowledged that soy proteins are usually well tolerated, and the occurrence of acute reactions depends on the individual hypersensitivity. However, total protein intake must be balanced with soy intake, and safety of the phytoestrogens must be confirmed on the long term.

4.3. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs)

The dietary fats composition is a crucial determinant of lipid concentrations in plasma [102]. Nonetheless, the dietary intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)—including Omega-3 and Omega-6—is frequently insufficient in children [103].

Dietary supplementation of PUFAs have shown to impact cardiovascular risk markers, such as TG, LDL-C and adhesion molecules, while also possessing anti-inflammatory properties [104,105]. In a randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 107 healthy children, PUFAs and low saturated fatty acids were able to significantly reduce markers of endothelial cell activation (i.e., adhesion molecules, E-selectin, ICAM-1 and lymphocyte levels), while increasing plasma concentration of Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) after receiving a 5-month daily intake of a milk enriched product [106].

Another functional food that has been studied in this context is the hempseed oil, which is notably rich in essential fatty acids, including Omega-3 PUFA α-linolenic acid (ALA) and Omega-6 PUFA linoleic acid (LA), with an LA/ALA ratio ranging between 2:1 and 3:1 [95]. The cholesterol-lowering effect of hempseed oil has been extensively assessed in animals and adult humans. However, a recent 8-week randomized controlled trial showed that HSO increases the content of total n-3 and n-6 PUFAs in red blood cells and improves the Omega-3 index, even in children with hyperlipidemia. Moreover, according to the findings of the study, hempseed oil exerted significant reductions in LDL-C (−14%) compared to the control [94]. Overall, emerging observations offer valuable insights for enhancing and complementing food intake with PUFAs. However, further studies are warranted to validate preliminary data.

4.4. Red Yeast Rice

Red yeast rice is a widely used and clinically tested cholesterol-lowering nutraceutical derived from the fermentation of standard rice by specific mycelia (usually Monascus purpureus Went) with the production of a pigment (making the rice red) and some bioactive compounds, among which monacolins are reversible inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaril Coenzyme A reductase (Figure 2) [107]. The most bioactive compound was monacolin K, which is chemically analogous to lovastatin. In adults, monacolin K significantly reduces cholesterolemia [108] while maintaining an acceptable safety profile [109]. To date, only one study has been conducted in children at increased cardiovascular risk, including those with familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) and familial combined hyperlipidemia, while following a step II diet [90]. The study, designed as a double-blinded, randomized cross-over trial, spanned 6 months in total, during which all participants completed the trial without experiencing any notable adverse effects. After 8 weeks of treatment, there was a significant reduction in TC, LDL-C, and ApoB levels by −18.5%, −25.1%, and −25.3%, respectively, while HDL-C remained unchanged. These findings were remarkable in terms of compliance, tolerability, and efficacy. Notably, the administered dose of Monacolin K was 3 mg/day, demonstrating impressive results comparable to those achieved with pravastatin (10 mg/day or more), indicating a potential synergistic effect with other bioactive components. A recent change in European Union (EU) regulations forbids the use of red yeast rice in children and adolescents because of the presumed (but not demonstrated) risk to health [110].

5. Discussion

Multiple nutraceuticals have shown efficacy in reducing lipid levels, as evidenced by the available clinical trials. However, it is important to note that no single dietary supplement can replace the importance of proper dietary counseling. Lifestyle changes and adherence to a correct Mediterranean diet showed a mean decrease of 9.5% in TC, 13.5% in LDL-C, and −10.9% in non-HDL-C plasma levels in a recent large retrospective study conducted on children with polygenic and familial hypercholestremia [111]. This may be sufficient to manage mild polygenic hypercholesterolemia.

Phytosterols and fiber-enriched foods are usually shown to be effective in reducing TC and LDL-C levels in children with FH or polygenic hypercholesterolemia or children affected by other secondary dyslipidaemias, especially when combined with a STEP I (daily fat intake < 30%, saturated FAs < 10%, cholesterol < 300 mg) or STEP II (saturated FAs 7%, cholesterol < 200 mg) diet. ApoB is also ameliorated after phytosterol intake, while contrasting results were observed after fiber intake. In contrast, no favorable variations have been observed in the endothelial function of phytosterol/sterol addition, and only two studies concerning this topic are inconclusive. Plant sterol/stanol and fiber were well received, with high compliance observed, particularly in the short term. Some gastrointestinal side effects would be expected if phytosterols are assumed with addition of artificial sweeteners. Noteworthy is the absence of significant adverse effects; nonetheless, abdominal discomfort or diarrhea were commonly reported symptoms with fiber supplementation. They could be even more frequent and severe when fibers are assumed with addition of artificial sweeteners. Functional foods incorporating phytosterols/stanols were associated with a notable decline in carotenoids, but not other vitamins, highlighting the importance of maintaining an adequate intake of vegetables and fruits to prevent nutritional deficiencies.

While randomized and controlled studies focusing on robust endpoints in children are lacking and infrequent, certain benefits have been noted, particularly in the short term, primarily relating to plant sterol/stanol and fibers. Many other bioactive compounds have demonstrated efficacy as cholesterol-lowering agents in adults (red yeast rice, berberine, bergamot polyphenol fraction, and artichoke extracts), but not in children. Presently, no dietary supplements have been shown to significantly reduce lipoprotein (a) levels, beyond L-carnitine and Coenzyme Q10, but this effect has never tested in children [112].

The European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel recommended that functional foods containing phytosterols to be considered for children with familial hypercholesterolemia, and as dietary additive supplementation rather than independent pharmaceutical treatment, especially with lifestyle modification [113,114]. Despite the limitation on the available evidence of dyslipidemia in pediatric age group, guidelines and evidence suggest that nutraceuticals, particularly fibers and phytosterols, can be utilized when combined with appropriate diet in children with genetic dyslipidemias starting from the age of 6 years old [10,115]. However, it could make sense if the treatment with cholesterol-lowering nutraceuticals are adequately dosed, long-term and effective.

6. Conclusions

Lifestyle and dietary modifications are recommended for any child or adolescent presenting with mild to moderate dyslipidemia. Phytosterols and fibers are deemed safe, while the other mentioned nutraceuticals may serve as possible efficacious additions to dietary treatment when combined with appropriate diet regimen. It is important to note that nutraceuticals should not be viewed as substitutes for diet or statins when they are medically indicated, as advised by the main international guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F.G.C.; data searching and selection of the bibliography, F.F., N.S.A., V.D.M. and A.F.G.C.; original draft preparation, F.F., V.D.M. and A.F.G.C.; supervision, A.F.G.C.; review and editing, N.S.A. and M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elisa Grandi for her support in formatting the manuscript according to the Journal’s requirements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ference, B.A.; Kastelein, J.J.P.; Ray, K.K.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Chapman, M.J.; Packard, C.J.; Laufs, U.; Oliver-Williams, C.; Wood, A.M.; Butterworth, A.S.; et al. Association of triglyceride-lowering LPL variants and LDL-C-lowering LDLR variants with risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA 2019, 321, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Pletcher, M.J.; Vittinghoff, E.; Clemons, A.M.; Jacobs, D.R.; Allen, N.B.; Alonso, A.; Bellows, B.K.; Oelsner, E.C.; Zeki Al Hazzouri, A.; et al. Association between cumulative low-density lipoprotein cholesterol exposure during young adulthood and middle age and risk of cardiovascular events. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, F.; Niglio, T.; Martino, E.; Paravati, V.; de Sanctis, L.; Guardamagna, O. Apolipoprotein B and Lipid Profile in Italian Children and Adolescents. J. Cardiovasc. Develop. Dis. 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Patrono, D.; Mancini, R.; Ramazzotti, E.; Borghi, C.; D’Addato, S.; BLIP Study group. Application of the Sampson equation to estimate LDL-C in children: Comparison with LDL direct measurement and Friedewald equation in the BLIP study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 1911–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Cholesterol in childhood. Pediatrics 1998, 101, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Daniels, S.R.; Kähönen, M.; Woo, J.G.; Sinaiko, A.R.; Viikari, J.S.A.; Bazzano, L.A.; Steinberger, J.; Urbina, E.M.; et al. Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels From Childhood to Adulthood and Cardiovascular Disease Events. JAMA, 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: Summary report. Pediatrics 2011, 128, S213e56. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Giovannini, M.; Bove, M.; Debellis, G.; Borghi, C. Effect of quantitative and qualitative diet prescription on children behavior after diagnosis of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 293, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiterovich, P.O. Recognition and management of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 4200–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Addato, S.; Fogacci, F.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Palmisano, S.; Baronio, F.; Biagi, C.; Borghi, C. Severe hypercholesterolaemia in a paediatric patient with congenital analbuminaemia. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 29, 316–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Stoian, A.P.; Vrablik, M.; Al Rasadi, K.; Banach, M.; Toth, P.P.; Rizzo, M. Nutraceuticals in the management of dyslipidemia: Which, when, and for whom? Could nutraceuticals help low-risk individuals with non-optimal lipid levels? Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, M.; Patti, A.M.; Giglio, R.V.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bajraktari, G.; Bruckert, E.; Descamps, O.; Djuric, D.M.; Ezhov, M.; et al. International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). The Role of Nutraceuticals in Statin Intolerant Patients. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, A.L.; Graham, I.; De Backer, G.; Wiklund, O.; Chapman, M.J.; Drexel, H.; Hoes, A.W.; Jennings, C.S.; Landmesser, U.; Pedersen, T.R.; et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Atherosclerosis 2016, 253, 281–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slavin, J.L. Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and resistant starch in white vegetables: Links to health outcomes. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 351S–355S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, R.; Clemente, G.; Cipriano, D.; Luongo, D.; Viscovo, D.; Patti, L.; Di Marino, L.; Giacco, A.; Naviglio, D.; Bianchi, M.A.; et al. Effects of the regular consumption of wholemeal wheat foods on cardiovascular risk factors in healthy people. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Story, L.; Sieling, B.; Chen, W.J.; Petro, M.S.; Story, J. Hypocholesterolemic effects of oat-bran or bean intake for hypercholesterolemic men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984, 40, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.P.; Hectorne, K.; Reynolds, H.; Balm, T.K.; Hunninghake, D.B. Cholesterol lowering effects of Psyllium Hydrophilic Mucilloid: Adjunct therapy to a prudent diet for patient with mild to moderate hypercholesterolemia. JAMA 1989, 261, 3419–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for carbohydrates and dietary fiber. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1462. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling: Health Claims; Oats and Coronary Heart Disease; Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to beta-glucans from oats and barley and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1236, 1299), increase in satiety leading to a reduction in energy intake (ID 851, 852), reduction of postprandial glycaemic responses (ID 821, 824), and “digestive function”. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2207; 1 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/ 2006, (ID850) pursuant-to article 13.

- Shinozaki, K.; Okuda, M.; Sasaki, S.; Kunitsugu, I.; Shigeta, M. Dietary fiber consumption decreases the risks of overweight and hypercholesterolemia in Japanese children. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 67, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.T. Dietary fiber for children: How much? Pediatrics 1995, 96, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Kranz, S.; Brauchla, M.; Slavin, J.L.; Miller, K.B. What do we know about dietary fiber intake in children and health? The effects of fiber intake on constipation, obesity, and diabetes in children. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.A.; Xie, C.; Garcia, A.L. Dietary fibre and health in children and adolescents. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, S.R.; Greer, F.R.; Committee on Nutrition. Lipid screening and cardiovascular health in childhood. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: Applications in Dietary Assessment; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Bollella, M.; Williams, C.L.; Strobino, B. Dietary predictors of cardiovascular risk factors among children in a 5-year health tracking study: Healthy Start. In Proceedings of the American Dietetic Association, Food & Nutrition Conference & Expo, San Antonio, TX, USA, 25–28 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B. Psyllium as therapeutic and drug delivery agent. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 334, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambuza, A.; Rungqu, P.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Miya, G.; Oriola, A.O.; Hosu, Y.S.; Oyedeji, O.O. Therapeutic Potential of Pectin and Its Derivatives in Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2024, 29, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Canga, A.; Fernandez Martınez, N.; Sahagún, A.M.; García Vieitez, J.J.; Díez Liébana, M.J.; Calle Pardo, A.P.; Castro Robles, L.J.; Sierra Vega, M. Glucomannan: Properties and therapeutic applications. Nutr. Hosp. 2004, 19, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuksan, V.; Jenkins, A.L.; Rogovik, A.L.; Fairgrieve, C.D.; Jovanovski, E.; Leiter, L.A. Viscosity rather than quantity of dietary fibre predicts cholesterol-lowering effect in healthy individuals. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1349–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq Butt, M.S.; Tahir-Nadeem, M.; Khan, M.K.; Shabir, R.; Butt, M.S. Oat: Unique among the cereals. Eur. J. Nutr. 2008, 47, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane, M.; McKay, J.; Pal, S. Effects of daily consumption of psyllium, oat bran and polyGlycopleX on obesity-related disease risk factors: A critical review. Nutrition 2019, 57, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunness, P.; Gidley, M.J. Mechanisms underlying the cholesterol lowering properties of soluble dietary fibre polysaccharides. Food Funct. 2010, 1, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.H.; Dugan, L.D.; Burns, J.H.; Sugimoto, D.; Story, K.; Drennan, K. A psyllium-enriched cereal for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia in children: A controlled, double-blind, cross-over study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 63, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Bayle, M.; Gonzalez-Requejo, A.; Asensio-Anton, J.; Ruiz-Jarabo, C.; Fernandez-Ruiz, M.L.; Baeza, J. The effect of fiber supplementation on lipid profile in children with hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 2001, 40, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, F.; Martino, E.; Morrone, F.; Carnevali, E.; Forcone, R.; Niglio, T. Effect of dietary supplementation with glucomannan on plasma total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol in hypercholesterolemic children. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2005, 15, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, K.; Wong, N.; Tong, A.; Bassin, S.; Iftner, C.; Nguyen, T.; Khoury, A.; Baker, S. Serum apolipoprotein and lipid profile effects of an oat-bran-supplemented, low-fat diet in children with elevated serum cholesterol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991, 623, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.L.; Bollella, M.C.; Strobino, B.A.; Boccia, L.; Campanaro, L. Plant stanol ester and bran fiber in childhood: Effects on lipids, stool weight and stool frequency in preschool children. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1999, 18, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneja, A.; Bhat, C.M.; Arora, A.; Kaur, A.P. Effect of incorporation of isabgol husk in a low fibre diet on faecal excretion and serum levels of lipids in adolescent girls. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 43, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, B.A.; Levine, D.M. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-period cross-over clinical trial of psyllium fiber in children with hypercholesterolemia. J. Pediatr. 1993, 123, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.K.; Vita, J.A.; Manuck, S.B.; Selwyn, A.P.; Kaplan, J.R. Psychosocial factors impair vascular responses of coronary arteries. Circulation 1991, 84, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauss, S.B.; Kwiterovich, P.O. Long-term safety and efficacy of low-fat diets in children and adolescents. Minerva Pediatr. 2002, 54, 305–313. [Google Scholar]

- The DISC Collaborative Research Group: The efficacy and safety of lowering dietary intake of total fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol in children with elevated LDL-C: The Dietary Intervention Study in Children (DISC). JAMA 1995, 273, 1429–1435. [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.L.; Bollella, M.; Spark, A.; Puder, D. Soluble fiber enhances the hypocholesterolemic effect of the step I diet in childhood. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1995, 14, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, S.A.; Cunha, D.B.; Sichieri, R.; Santana da Silva, L.C. Effects of psyllium on LDL-cholesterol concentrations in Brazilian children and adolescents: A randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardamagna, O.; Abello, F.; Cagliero, P.; Visioli, F. Could dyslipidemic children benefit from glucomannan intake? Nutrition 2013, 29, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livieri, C.; Novazi, F.; Lorini, R. The use of highly purified glucomannan- based fibers in childhood obesity. Pediatr. Med. Chir. 1992, 14, 195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H.V.T.; Jovanovski, E.; Zurbau, A.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Au-Yeung, F.; Jenkins, A.L.; Duvnjak, L.; Leiter, L.; Vuksan, V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of the effect of konjac glucomannan, a viscous soluble fiber, on LDL cholesterol and the new lipid targets non-HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, M.; Spark, A.; Berezin, S.; Schwarz, S.; Medow, M.; Newman, L.J. Treatment of type IIa hyperlipidemia in childhood by a simplified American Heart Association diet and fiber supplementation. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1990, 144, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, F.; Puddu, P.E.; Pannarale, G.; Colantoni, C.; Martino, E.; Niglio, T.; Zanoni, C.; Barillà, F. Low dose chromium-polynicotinate or policosanol is effective in hypercholesterolemic children only in combination with glucomannan. Atherosclerosis 2013, 228, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.C.; Davidson, M.H.; Ingram, K.A.; Veith, P.E.; Bell, M.; Gugger, E. Lipid responses to consumption of a beta-glucan containing ready- to-eat cereal in children and adolescents with mild- to-moderate primary hypercholesterolemia. Nutr. Res. 2003, 23, 1527–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenschein, S.; Torres, E.; Kushmaul, E.; Crawford, J.; Fixler, D. Effect of oat bran/ soy protein in hypercholesterolemic children. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1991, 623, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavoral, J.H.; Hannan, P.; Fields, D.J.; Hanson, M.N.; Frantz, I.D.; Kuba, K.; Elmer, P.; Jacobs, D.R. The hypolipidemic effect of locust bean gum food products in familial hypercholesterolemic adults and children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 38, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiterovich, P.O.; Chen, S.C.; Virgil, D.G.; Schweitzer, A.; Arnold, D.R.; Kratz, L.E. Response of obligate heterozygotes for phytosterolemia to a low-fat diet and to a plant sterol ester dietary challenge. J. Lipid Res. 2003, 44, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G.R.; Grundy, S.M. History and development of plant sterols and stanol esters for cholesterol lowering purposes. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 3D–9D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifton, P.M.; Noakes, M.; Sullivan, D.; Erichsen, N.; Ross, D.; Annison, G.; Fassoulakis, A.; Cehun, M.; Nestel, P. Cholesterol-lowering effects of plant sterol esters differ in milk, yoghurt, bread and cereal. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Miettinen, T.A. New biologically active lipids in food, health food and pharmaceuticals. Lipid-forum; Scandinavian forum for lipid research and technology. In Proceedings of the 19th Nordic Lipid Symposium, Ronneby, Sweden, 15–18 June 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tammi, A.; Rönnemaa, T.; Gylling, H.; Rask-Nissilä, L.; Viikari, J.; Tuominen, J.; Pulkki, K.; Simell, O. Plant stanol ester margarine lowers serum total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentrations of healthy children: The STRIP project. Special Turku Coronary Risk Factors Intervention Project. J. Pediatr. 2000, 136, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Miettinen, T.A. Inheritance of cholesterol metabolism of probands with high or low cholesterol absorption. J. Lipid Res. 2002, 43, 1472–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, T.A.; Tilvis, R.S.; Kesäniemi, Y.A. Serum plant sterols and cholesterol precursors reflect cholesterol absorption and synthesis in volunteers of a randomly selected male population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 131, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Siimes, M.A.; Miettinen, T.A. Sitostanol ester margarine in dietary treatment of children with familial hypercholesterolemia. J. Lipid Res. 1995, 36, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, S.A.; Sichieri, R.; Moreira, A.S.B.; Souza, D.O.; Cabral, C.T.F.; Gianinni, D.T.; Cunha, D.B. Phytosterol-enriched milk lowers LDL-cholesterol levels in Brazilian children and adolescents: Double-blind, cross-over trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammi, A.; Rönnemaa, T.; Miettinen, T.A.; Gylling, H.; Rask-Nissilä, L.; Viikari, J.; Tuominen, J.; Marniemi, J.; Simell, O. Effects of gender, apolipoprotein E phenotype and cholesterol lowering by plant stanol esters in children: The STRIP study. Special Turku coronary risk factor intervention project. Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, A.L.; Ose, L.; Nenseter, M.S.; Ntanios, F.Y. Plant sterol ester-enriched spread lowers plasma total and LDL cholesterol in children with familial hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amundsen, A.L.; Ntanios, F.; Put, N.V.; Ose, L. Long-term compliance and changes in plasma lipids, plant sterols and carotenoids in children and parents with FH consuming plant sterol ester-enriched spread. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garoufi, A.; Vorre, S.; Soldatou, A.; Tsentidis, C.; Kossiva, L.; Drakatos, A.; Marmarinos, A.; Gourgiotis, D. Plant sterols–enriched diet decreases small, dense LDL-cholesterol levels in children with hypercholesterolemia: A prospective study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketomäki, A.M.; Gylling, H.; Antikainen, M.; Siimes, M.A.; Miettinen, T.A. Red cell and plasma plant sterols are related during consumption of plant stanol and sterol ester spreads in children with hypercholesterolemia. J. Pediatr. 2003, 142, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guardamagna, O.; Abello, F.; Baracco, V.; Federici, G.; Bertucci, P.; Mozzi, A.; Mannucci, L.; Gnasso, A.; Cortese, C. Primary hyperlipidemias in children: Effect of plant sterol supplementation on plasma lipids and markers of cholesterol synthesis and absorption. Acta Diabetol. 2011, 48, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakulj, L.; Vissers, M.N.; Rodenburg, J.; Wiegman, A.; Trip, M.D.; Kastelein, J.J. Plant stanols do not restore endothelial function in prepubertal children with familial hypercholesterolemia despite reduction of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. J. Pediatr. 2006, 148, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jongh, S.; Vissers, M.N.; Rol, P.; Bakker, H.D.; Kastelein, J.J.; Stroes, E.S. Plant sterols lower LDL cholesterol without improving endothelial function in prepubertal children with familial hypercholesterolaemia. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2003, 26, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, L.M.; Pugliese, C. Phytosterol supplementation in the treatment of dyslipidemia in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2020, 39, e2019389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuMweis, S.S.; Barake, R.; Jones, P.J. Plant sterols/stanols as cholesterol lowering agents: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Nutr. Res. 2008, 52, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, T.A.; Puska, P.; Gylling, H.; Vanhanen, H.; Vartiainen, E. Reduction of serum cholesterol with sitostanol-ester margarine in a mildly hypercholesterolemic population. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 1308–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Shafiq, N.; Arora, A.; Singh, M.; Kumar, R.; Malhotra, S. Dietary interventions (plant sterols, stanols, omega-3 fatty acids, soy protein and dietary fibers) for familial hypercholesterolaemia [Review]. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD001918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demonty, I.; Ras, R.T. The effect of plant sterols on serum triglyceride concentrations is dependent on baseline concentrations: A pooled analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2013, 52, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, T.A.; Gylling, H. Effect of statins on noncholesterol sterol levels: Implications for use of plant stanols and sterols. Am. J. Cardiol. 2005, 96, 40D–46D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuorio, A.; Kovanen, P.T. Decreasing the cholesterol burden in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia children by dietary plant stanol esters. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glueck, C.J.; Speirs, J.; Tracy, T.; Streicher, P.; Illig, E.; Vandegrift, J. Relationships of serum plant sterols (phytosterols) and cholesterol in 595 hypercholesterolemic subjects, and familial aggregation of phytosterols, cholesterol, and premature coronary heart disease in hyperphytosterolemic probands and their first-degree relatives. Metabolism 1991, 40, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, G.; Cullen, P. Plasma sitosterol elevations are associated with an increased incidence of coronary events in men: Results of a nested case- control analysis of the Prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2006, 16, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.; Ceglarek, U. Elevated campesterol serum levels—A significant predictor of incident myocardial infarction: Results of the population-based Monica/KORA follow-up study 1994–2005. Circulation 2006, 114, II-884. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, H.; Nomura, A.; Ogura, M.; Ikewaki, K.; Ishigaki, Y.; Inagaki, K.; Tsukamoto, K.; Dobashi, K.; Nakamura, K.; Hori, M.; et al. Diagnosis and management of sitosterolemia 2021. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.L.; Tomaro-Duchesneau, C.; Martoni, C.J.; Prakash, S. Cholesterol lowering with bile salt hydrolase-active probiotic bacteria, mechanism of action, clinical evidence, and future direction for heart health applications. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2013, 13, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, A.; Amaretti, A.; Leonardi, A.; Boschetti, E.; Danesi, F.; Matteuzzi, D.; Roncaglia, L.; Raimondi, S.; Rossi, M. Cholesterol-lowering probiotics: In vitro selection and in vivo testing of bifidobacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 8273–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilzer, A.; Park, Y. Implication of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) in human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 488–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Musazadeh, V. Probiotics act as a potent intervention in improving lipid profile: An umbrella systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardamagna, O.; Amaretti, A.; Puddu, P.E.; Raimondi, S.; Abello, F.; Cagliero, P.; Rossi, M. Bifidobacteria supplementation: Effects on plasma lipid profiles in dyslipidemic children. Nutrition 2014, 30, 831–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Scientific Opinion on the maintenance of the list of QPS biological agents intentionally added to food and feed (2012 update). EFS J. 2012, 10, 3020. [Google Scholar]

- Guardamagna, O.; Abello, F.; Baracco, V.; Stasiowska, B.; Martino, F. The treatment of hypercholesterolemic children: Efficacy and safety of a combination of red yeast rice extract and policosanols. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weghuber, D.; Widhalm, K. Effect of 3-month treatment of children and adolescents with familial and polygenic hypercholesterolaemia with a soya-substituted diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhalm, K.; Brazda, G.; Schneider, B.; Kohl, S. Effect of soy protein diet versus standard low fat, low cholesterol diet on lipid and lipoprotein levels in children with familial or polygenic hypercholesterolemia. J. Pediatr. 1993, 123, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurin, D.; Jacques, H.; Moorjani, S.; Steinke, F.H.; Gagné, C.; Brun, D.; Lupien, P.J. Effects of a soy-protein beverage on plasma lipoproteins in children with familial hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bo’, C.; Deon, V.; Abello, F.; Massini, G.; Porrini, M.; Riso, P.; Guardamagna, O. Eight-week hempseed oil intervention improves the fatty acid composition of erythrocyte phospholipids and the omega-3 index, but does not affect the lipid profile in children and adolescents with primary hyperlipidemia. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldi, F.; Deon, V.; Del Bo’, C.; Vendrame, S.; Porrini, M.; Riso, P.; Guardamagna, O. Effect of short-term hazelnut consumption on DNA damage and oxidized LDL in children and adolescents with primary hyperlipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 57, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargari, G.; Deon, V.; Taverniti, V.; Gardana, C.; Denina, M.; Riso, P.; Guardamagna, O.; Guglielmetti, S. Evidence of dysbiosis in the intestinal microbial ecosystem of children and adolescents with primary hyperlipidemia and the potential role of regular hazelnut intake. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros, E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients 2010, 2, 652–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deon, V.; Del bo’, C. Effect of hazelnut on serum lipid profile and fatty acid composition of erythrocyte phospholipids in children and adolescents with primary hyperlipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-González, C.; Ciudad, C.J.; Noé, V.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Health benefits of walnut polyphenols: An exploration beyond their lipid profile. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3373–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, G.; Baroni, L. Soy, Soy foods and their role in vegetarian diets. Nutrients 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helk, O.; Widhalm, K. Effects of a low-fat dietary regimen enriched with soy in children affected with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 36, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, U.S.; Callaway, J.C.; Erkkilä, A.T.; Gynther, J.; Uusitupa, M.I.; Järvinen, T. Effects of hempseed and flaxseed oils on the profile of serum lipids, serum total and lipoprotein lipid concentrations and haemostatic factors. Eur. J. Nutr. 2006, 45, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patch, C.S.; Tapsell, L.C.; Mori, T.A.; Meyer, B.J.; Murphy, K.J.; Mansour, J.; Noakes, M.; Clifton, P.M.; Puddey, I.B.; Beilin, L.J.; et al. The use of novel foods enriched with longchain n-3 fatty acids to increase dietary intake: A comparison of methodologies assessing nutrient intake. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, T.A.; Glickstein, S.B.; Rowe, J.D.; Soni, P.N. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other lipids: A review. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2012, 6, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and inflammatory diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83 (Suppl. S6), 1505S–1519S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, J.; Wärnberg, J.; García-Mármol, E.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, M.; Diaz, L.E.; Gomez-Martínez, S.; Cueto, B.; López-Huertas, E.; Cepero, M.; Boza, J.J.; et al. Daily consumption of milk enriched with fish oil, oleic acid, minerals and vitamins reduces cell adhesion molecules in healthy children. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.; Fogacci, F.; Stoian, A.P.; Toth, P.P. Red Yeast Rice for the Improvement of Lipid Profiles in Mild-to-Moderate Hypercholesterolemia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Fogacci, F.; Zambon, A. Red yeast rice for hypercholesterolemia: JACC focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogacci, F.; Banach, M. Lipid and Blood Pressure Meta-analysis Collaboration (LBPMC) Group, & International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). Safety of red yeast rice supplementation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 143, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R0860 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Massini, G.; Capra, N.; Buganza, R.; Nyffenegger, A.; de Sanctis, L.; Guardamagna, O. Mediterranean dietary treatment in hyperlipidemic children: Should it be an option? Nutrients 2022, 14, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogacci, F.; Di Micoli, V.; Sabouret, P.; Giovannini, M.; Cicero, A.F.G. Lifestyle and Lipoprotein(a) Levels: Does a Specific Counseling Make Sense? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gylling, H.; Plat, J.; Turley, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Ellegård, L.; Jessup, W.; Jones, P.J.; Lütjohann, D.; Maerz, W.; Masana, L.; et al. Plant sterols and plant stanols in the management of dyslipidaemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capra, M.E.; Biasucci, G.; Banderali, G.; Vania, A.; Pederiva, C. Diet and Lipid-Lowering Nutraceuticals in Pediatric Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Children 2024, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banderali, G.; Capra, M.E.; Viggiano, C.; Biasucci, G.; Pederiva, C. Nutraceuticals in Paediatric Patients with Dyslipidaemia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).