Pulse Consumption and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Pulse Consumption

3.3. Outcome Measures

3.4. Observational Studies

3.5. Intervention Studies

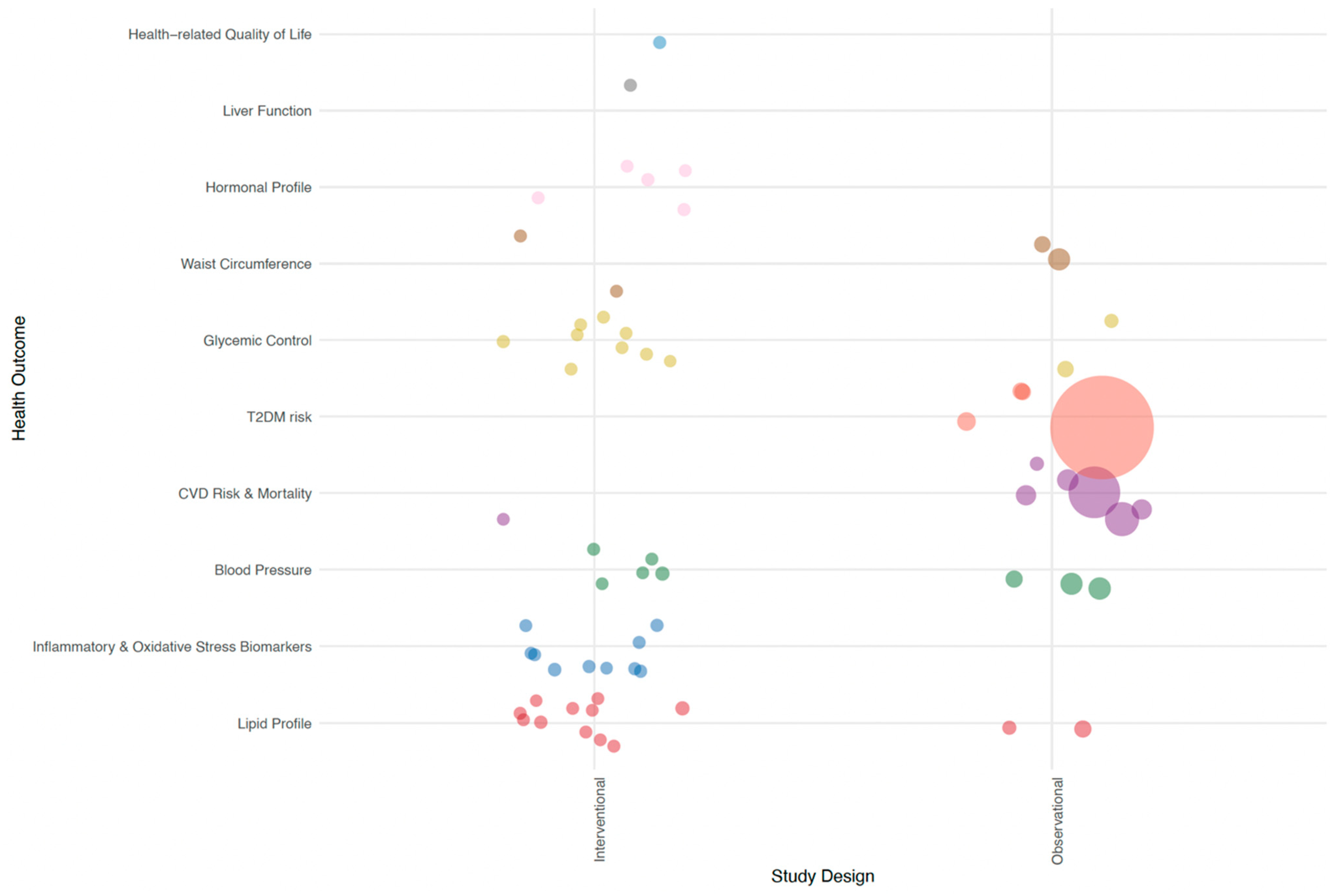

3.6. Identifying Research Gaps Related to Study Design

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bessada, S.M.; Barreira, J.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Pulses and food security: Dietary protein, digestibility, bioactive and functional properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, M.; Uebersax, M.A.; Siddiq, F. Global production, trade, processing and nutritional profile of dry beans and other pulses. In Dry Beans and Pulses: Production, Processing, and Nutrition, 2nd ed.; Siddiq, M., Uebersax, M.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Pulses. Available online: http://www.fao.org/es/faodef/fdef04e.htm (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Calles, T.; del Castello, R.; Baratelli, M.; Xipsiti, M.; Navarro, D.K. The International Year of Pulses: Final Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dilis, V.; Trichopoulou, A. Nutritional and health properties of pulses. Med. J. Nutrition Metab. 2009, 1, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, V. Nutritional and health benefits of dried beans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100 (Suppl. S1), 437S–442S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N. Pulses: An overview. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.; Hillen, C.; Garden Robinson, J. Composition, nutritional value, and health benefits of pulses. Cereal Chem. 2017, 94, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Marinangeli, C.P.F.; Pigat, S.; Bompola, F.; Campbell, J.; Pan, Y.; Curran, J.M.; Cai, D.J.; Jaconis, S.Y.; Rumney, J. Pulse intake improves nutrient density among US adult consumers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didinger, C.; Thompson, H. Motivating pulse-centric eating patterns to benefit human and environmental well-being. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Agriculture; US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Havemeier, S.; Erickson, J.; Slavin, J. Dietary guidance for pulses: The challenge and opportunity to be part of both the vegetable and protein food groups. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinangeli, C.P.; Curran, J.; Barr, S.I.; Slavin, J.; Puri, S.; Swaminathan, S.; Tapsell, L.; Patterson, C.A. Enhancing nutrition with pulses: Defining a recommended serving size for adults. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Pandey, G. Biofortification of pulses and legumes to enhance nutrition. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Buddemeyer, S.; Fassett, C.M.; Gans, W.M.; Johnston, K.M.; Lungu, E.; Savelle, R.L.; Tolani, P.N.; Dahl, W.J. Pulses and prevention and management of chronic disease. In Health Benefits of Pulses; Dahl, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Considine, M.J.; Siddique, K.H.; Foyer, C.H. Nature’s pulse power: Legumes, food security and climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1815–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, J.; Wyatt, A.J. The role of pulses in sustainable and healthy food systems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Multiple benefits of legumes for agriculture sustainability: An overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.S.; Das, A.; Yadav, G.S.; Lal, R. Legumes for Soil Health and Sustainable Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O‘Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O‘Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O‘Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Kastner, M.; Moher, D. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askari, M.; Daneshzad, E.; Jafari, A.; Bellissimo, N.; Azadbakht, L. Association of nut and legume consumption with Framingham 10 year risk of general cardiovascular disease in older adult men: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 42, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeon, M.E.; Felix, C.; Fornasini, M.; Zertuche, F.; Largo, C.; Paucar, M.J.; Ponce, L.; Rangarajan, S.; Yusuf, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type-2 and their association with intake of dairy and legume in Andean communities of Ecuador. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papanikolaou, Y.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Bean consumption is associated with greater nutrient intake, reduced systolic blood pressure, lower body weight, and a smaller waist circumference in adults: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.; Fanidi, A.; Bishop, T.R.P.; Sharp, S.J.; Imamura, F.; Dietrich, S.; Akbaraly, T.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Byberg, L.; et al. Associations of total legume, pulse, and soy consumption with incident type 2 diabetes: Federated meta-analysis of 27 studies from diverse world regions. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Díaz-López, A.; Rosique-Esteban, N.; Ros, E.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Fitó, M.; Serra-Majem, L.; Arós, F.; et al. Legume consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes incidence in adults: A prospective assessment from the PREDIMED study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 906–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yan, N.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.H.; Ma, L. Legume consumption and risk of hypertension in a prospective cohort of Chinese men and women. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Hu, B.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Wang, C.; Yan, R.; Rangarajan, S.; Tse, L.A.; Yusuf, S.; Liu, X.; et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: A prospective study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4316–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Gupta, R.; Mohan, V.; Lear, S.; et al. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, F.; Sarrafzadegan, N.; Mohammadifard, N.; Sadeghi, M.; Mansourian, M. Intake of legumes and the risk of cardiovascular disease: Frailty modeling of a prospective cohort study in the Iranian middle-aged and older population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, F.; Haghighatdoost, F.; Mohammadifard, N.; Mansourian, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Roohafza, H.; Khani, A.; Sarrafzadegan, N. The longitudinal association between soybean and non-soybean legumes intakes and risk of cardiovascular disease: Isfahan cohort study. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2864–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, C.; Becerra-Tomas, N.; Bullo, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Corella, D.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Aros, F.; Schroder, H.; Fito, M.; et al. Legume consumption and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality in the PREDIMED study. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, M.; Soderberg, S.; Uusitalo, U.; Tuomilehto, J.; Shaw, J.E.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Kowlessur, S.; Pauvaday, V.; Magliano, D.J. High consumption of pulses is associated with lower risk of abnormal glucose metabolism in women in Mauritius. Diabet. Med. 2015, 32, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahradka, P.; Wright, B.; Weighell, W.; Blewett, H.; Baldwin, A.; Karmin, O.; Guzman, R.P.; Taylor, C.G. Daily non-soy legume consumption reverses vascular impairment due to peripheral artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2013, 230, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, S.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Vatanparast, H.; Zello, G.A. A pulse-based diet is effective for reducing total and LDL-cholesterol in older adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 (Suppl. S1), S103–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, T.J.; Albert, P.S.; Zhang, Z.; Bagshaw, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Ulbrecht, J.; Miller, C.K.; Bobe, G.; Colburn, N.H.; Lanza, E. Consumption of a legume-enriched, low-glycemic index diet is associated with biomarkers of insulin resistance and inflammation among men at risk for colorectal cancer. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirmiran, P.; Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Azizi, F. Therapeutic lifestyle change diet enriched in legumes reduces oxidative stress in overweight type 2 diabetic patients: A crossover randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Hosseini, S.; Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Azizi, F. Legume consumption increase adiponectin concentrations among type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized crossover clinical trial. Endocrinol. Diabetes Nutr. 2019, 66, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf-Bank, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Faghihimani, E.; Azadbakht, L. Effect of non-soy legume consumption on inflammation and serum adiponectin levels among first-degree relatives of patients with diabetes: A randomized, crossover study. Nutrition 2015, 31, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraf-Bank, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Faghihimani, E.; Azadbakht, L. Effects of legume-enriched diet on cardiometabolic risk factors among individuals at risk for diabetes: A crossover study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winham, D.M.; Hutchins, A.M.; Johnston, C.S. Pinto bean consumption reduces biomarkers for heart disease risk. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lanza, E.; Ross, A.C.; Albert, P.S.; Colburn, N.H.; Rovine, M.J.; Bagshaw, D.; Ulbrecht, J.S.; Hartman, T.J. A high-legume low-glycemic index diet reduces fasting plasma leptin in middle-aged insulin-resistant and -sensitive men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Fallah-Ghohroudi, A.; Azizi, F. Non-soya legume-based therapeutic lifestyle change diet reduces inflammatory status in diabetic patients: A randomised cross-over clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Mirmiran, P.; Hedayati, M.; Azizi, F. Substitution of red meat with legumes in the therapeutic lifestyle change diet based on dietary advice improves cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight type 2 diabetes patients: A cross-over randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Hadaegh, F.; Mirmiran, P.; Daneshpour, M.S.; Mahdavi, M.; Azizi, F. Effect of legumes in energy reduced Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on blood pressure among overweight and obese type 2 diabetic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, M.; Gharaaghaji, R.; Gargari, B.P. The effects of legumes on metabolic features, insulin resistance and hepatic function tests in women with central obesity: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; McBreairty, L.E.; Zello, G.A.; Pierson, R.A.; Gordon, J.J.; Serrao, S.B.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chizen, D.R. A pulse-based diet and the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes diet in combination with health counseling and exercise improve health-related quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 41, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollard, R.C.; Luhovyy, B.L.; Panahi, S.; Nunez, M.; Hanley, A.; Anderson, G.H. Regular consumption of pulses for 8 weeks reduces metabolic syndrome risk factors in overweight and obese adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108 (Suppl. S1), S111–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeiyan, A.; Pourghassem-Gargari, B.; Zarrin, R.; Fereidooni, J.; Alizadeh, M. Randomized controlled trial on the effects of legumes on cardiovascular risk factors in women with abdominal obesity. ARYA Atheroscler. 2015, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.M.G.; Peterson, E.J.; Gaston, M.E.; Kuo, W.Y.; Miles, M.P. Eight weeks of lentil consumption attenuates insulin resistance progression without increased gastrointestinal symptom severity: A randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Res. 2022, 106, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslani, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Alipur, B.; Bahadoran, Z.; Abbassalizade Farhangi, M. Lentil sprouts effect on serum lipids of overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Health Promot. Perspect. 2015, 5, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Human adult participants (age ≥ 18 y), except pregnant women |

| Concept/intervention | Must involve the consumption of whole pulses—whether raw, cooked, canned, or sprouted—for a period extending beyond 2 wk Must quantify pulse consumption, specifying the amount in servings per day or week, or grams per day or week, for at least 2 distinct categories |

| Outcomes | Any direct measure of physical health that could be influenced by pulse consumption. This definition of included outcomes was operationalized as any measurable endpoints that could be categorized as lipid profile, blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, oxidative stress biomarkers, glycemic control, metabolic syndrome and waist circumference, liver function, hormonal profile, CVD risk and mortality, T2DM risk and mortality, or overall function and well-being. This encompassing criterion allowed us to consider a comprehensive range of indicators reflective of the multifaceted impact of pulse intake on health. |

| Study design | Analytical studies (exclude case series, case reports, and qualitative studies) |

| Other | Research studies presenting original data published in peer-reviewed journals. Available in full text in the English language. |

| Reference | Study Design | Country | Sample Size and Population | Pulse Type | Dietary Assessment | Pulse Dose | Duration | Main Outcomes | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Askari et al., 2021 [23] | Cross-sectional | Iran | 267 men (age ≥ 60 y) | Lentils, chickpeas, cotyledon, beans, and peas | FFQ |

| NA |

|

|

| Baldeón et al., 2021 [24] | Cross-sectional | Ecuador | 1997 participants in the Ecuadorian cohort of the international PURE epidemiological study (72.1% women; mean age 51 ± 10 y; 62.8% low or medium income) | Beans, lentils, peas, fava beans, chickpeas, and lupins | FFQ |

| NA |

|

|

| Papanikolaou et al., 2008 [25] | Cross-sectional | US | 8229 men and women (age ≥ 20 y) from the 1999–2002 NHANES; excluded pregnant or lactating females | Baked beans, variety beans (pinto, kidney, etc.), variety beans and/or baked beans | 24 h food recall |

| NA |

|

|

| Pearce et al., 2021 [26] | Federated meta-analysis | Multiple regions | 729,998 participants from 27 prospective cohorts | Pulse (defined as consumption of peas, beans, chickpeas, and lentils) | Of the 27 cohorts, 17 used semi-quantitative FFQs, 4 used a quantitative dietary questionnaire, 3 used an interviewer-administered dietary history, 2 used a 24 h recall, and 1 used either an FFQ or a quantitative dietary questionnaire |

| NA |

|

|

| Becerra-Tomás et al., 2018 [27] | Prospective cohort | Spain | 3349 men (age 55–80 y) and women (age 60–80 y) without CVD at enrollment but with high cardiovascular risk | Lentils, chickpeas, dry beans, and fresh peas | Semi-quantitative FFQ |

| Follow-up: 4.3 y |

|

Lentil:

|

| Guo et al., 2020 [28] | Prospective cohort | China | 8758 men and women (not pregnant, age ≥ 30 y) | Non-soybean dry legume consumption (e.g., mung, adzuki, red kidney, and pinto) | 24 h food recall Household food inventory weighing |

| Median follow-up: 6.0 y |

|

Total legumes:

|

| Liu et al., 2021 [29] | Prospective cohort | China | 41,243 men and women (age 35–70 y) | Beans, lentils, chickpeas, black beans, peas, and black-eyed peas | FFQ |

| Median follow-up: 8.9 y |

|

|

| Miller et al., 2017 [30] | Prospective cohort | 18 countries in 7 regions (North America and Europe, South America, the Middle East, South Asia, China, Southeast Asia, and Africa) | 135,335 men and women (age 35–70 y) | Beans, black beans, lentils, peas, chickpeas, and black-eyed peas | FFQ |

| Median follow-up: 7.4 y |

|

|

| Nouri et al., 2016 [31] | Prospective cohort | Iran | 5398 men and women (age ≥ 35 y) | Legumes other than soybean | FFQ |

| Median follow-up: 6.8 y |

|

Non-soybean:

|

| Nouri et al., 2021 [32] | Prospective cohort | Iran | 5432 men and women (age ≥ 19 y), mentally competent and not pregnant | Soybean and non-soybeans (lentils, peas, beans, and mung beans) | FFQ |

| Median follow-up: 13 y |

|

Long-term non-soybean intake:

|

| Papandreou et al., 2019 [33] | Prospective cohort | Spain | 7212 men (age 55–80 y) and women (age 60–80 y) without CVD at enrollment but with high CVD risk | Lentils (Lens culinaris), chickpeas (Cicer arietinum), dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and fresh peas, (Cajanus cajan) | FFQ |

Consumption reported as average daily intake in grams, adjusted for total energy intake:

| Median follow-up: 6 y |

|

Total legumes:

|

| Wennberg et al., 2015 [34] | Prospective cohort | Mauritius | 1421 men and women (age 30–64 y) | Pulse (e.g., lentils, chickpeas, beans, and peas) | FFQ 24 h food recall |

| Median follow-up: 6 y |

|

Women:

|

| Zahradka et al., 2013 [35] | Before-and-after | Canada | 26 men and women (age ≥ 40 y) with PAD | Beans (pinto, kidney, black, and navy), peas, lentils, chickpeas | 3-day dietary record |

| 8 wk |

|

Non-soybean legume:

|

| Abeysekara et al., 2012 [36] | Randomized crossover | Canada | 87 men and women (mean age 59.7 y; mean BMI 27.5 ± 4.5) | Green lentils, red split lentils, chickpeas, yellow split peas, and pinto, fava, broad, black, and kidney beans | FFQ |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Hartman et al., 2010 [37] | Randomized crossover | US | 64 men (mean age 54.5 y) characterized for colorectal adenomas and IR status | Navy, pinto, kidney, and black beans | 3-day dietary record |

| 4 wk |

|

|

| Mirmiran et al., 2018 [38] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 40 men and women (age 50–75 y, BMI 25–30) with diabetes | Non-soybean (e.g., lentils, chickpeas, peas, and beans) | 3-day dietary record |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Mirmiran et al., 2019 [39] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 31 men and women (age 50–75 y; BMI 25–30) with T2DM | Lentils, chickpeas, peas, or beans | 3-day dietary record |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2015 [40] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 26 men and women (age ≥ 30 y), first-degree relatives of patients with T2DM | Pinto beans and brown lentils | 1-day dietary record |

| 6 wk |

|

|

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2016 [41] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 26 men and women (mean age 50 ± 6.58 y), first-degree relatives of patients with T2DM | Pinto beans and brown lentils | 1-day dietary record |

| 6 wk |

|

|

| Winham et al., 2007 [42] | Randomized crossover | US | 16 men and women (age 22–65 y) with fasting insulin ≥ 15 uIU/mL | Pinto beans, black-eyed peas | 24 h food recall |

| 8 wk |

|

Pinto beans:

|

| Zhang et al., 2011 [43] | Randomized crossover | US | 64 men (age 35–75 y), nonsmoking with no history of IBD, stroke, diabetes, or colorectal or any cancers | Pinto, navy, kidney, lima, and black beans | 24 h food recall |

| 4 wk |

|

|

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 [44] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 40 men and women (age 50–75 y) with T2DM, nonsmoking | Lentils, chickpeas, peas, beans | 3-day dietary record |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 [45] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 32 men and women (age 58.1 ± 6.0 y) with T2DM, nonsmoking | Lentils, chickpeas, peas, beans | 3-day dietary record |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2022 [46] | Randomized crossover | Iran | 300 men and women (mean age 55.4 y; mean BMI 30.4) with T2DM | Lentils, chickpeas, peas, beans | 3-day dietary record |

| 16 wk |

|

|

| Alizadeh et al., 2014 [47] | Randomized parallel | Iran | 42 premenopausal women | Beans (white, red, and wax), chickpeas, cowpeas, lentils, and split peas | Food diaries |

| 6 wk |

|

|

| Kazemi et al., 2020 [48] | Randomized parallel | Canada | 55 women (age 18–35 y) with PCOS | Lentils, beans, split peas, and chickpeas | Face-to-face counseling |

| 16 wk |

|

|

| Mollard et al., 2012 [49] | Randomized parallel | Canada | 40 men and women (aged 35–55 y; BMI 28–39.9), nonsmoking | Lentils (Nupak), chickpeas (Nupak), yellow split peas (Nupak), and navy beans (Frema) | 24 h food recall pulse log |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Safaeiyan et al., 2015 [50] | Randomized parallel | Iran | 34 premenopausal women (age 20–50 y) with abdominal obesity and WC > 88 cm | Non-soy legumes, including red, white, and wax beans; cowpea, chickpeas, split peas; and lentil | 3-day dietary record |

| 6 wk |

|

|

| Wilson et al., 2022 [51] | Randomized parallel | US | 30 men and women (age 18–70 y) with abdominal obesity (WC ≥ 40 in. and ≥35 in., respectively) but without diabetes | Lentils | DHQ III 24 h food recall |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Aslani et al., 2015 [52] | Randomized parallel | Iran | 39 men and women (age 30–65 y) with overweight or obesity and T2DM | Lentil sprout | Weekly calls to confirm lentil sprout consumption |

| 8 wk |

|

|

| Reference | Study Design | Population | Pulse Intake | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture vs. Type a | Pulse Type | |||||||||||

| Askari et al., 2021 [23] | Cross-sectional | Men | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Bean | Cotyledon | ||||

| Baldeón et al., 2021 [24] | Cross-sectional | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Bean | Fava bean, lupin | ||||

| Papanikolaou et al., 2008 [25] | Cross-sectional | Men and women | Mixture | Bean | Pinto bean | Kidney bean | ||||||

| Pearce et al., 2021 [26] | Federated meta-analysis | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Bean | |||||

| Wennberg et al., 2015 [34] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Liu et al., 2021 [29] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea, black-eyed pea | Beans | Black bean | ||||

| Miller et al., 2017 [30] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea, black-eyed pea | Beans | Black bean | ||||

| Nouri et al., 2016 [31] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea, black-eyed pea | Beans | Black bean | ||||

| Nouri et al., 2021 [32] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Dry pea | Beans | Mung bean | |||||

| Guo et al., 2020 [28] | Cohort | Men and women | Mixture | Pinto bean | Red kidney bean | Mung, adzuki bean | ||||||

| Becerra-Tomás et al., 2018 [27] | Cohort | Men and women with high CVD risk | Type | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry bean | ||||||

| Papandreou et al., 2019 [33] | Cohort | Men and women with high CVD risk | Type | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry bean | ||||||

| Zahradka et al., 2013 [35] | Before-and-after | Men and women with PAD | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | Pinto bean | Kidney bean | Black bean | Navy bean | |

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2016 [41] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with high T2DM risk | Mixture | Lentil | Pinto bean | |||||||

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2015 [40] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with high T2DM risk | Mixture | Lentil | Pinto bean | |||||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 [44] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 [45] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2022 [46] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Mirmiran et al., 2018 [38] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Mirmiran et al., 2019 [39] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Dry pea | Beans | |||||

| Abeysekara et al., 2012 [36] | Randomized crossover | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Split pea | Pinto bean | Kidney bean | Black bean | Fava, broad bean | ||

| Hartman et al., 2010 [37] | Randomized crossover | Men | Mixture | Pinto bean | Kidney bean | Black bean | Navy bean | |||||

| Zhang et al., 2011 [43] | Randomized crossover | Men | Mixture | Pinto bean | Kidney bean | Black bean | Navy bean | Lima bean | ||||

| Winham et al., 2007 [42] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with IR | Type | Black-eyed pea | Pinto bean | |||||||

| Alizadeh et al., 2014 [47] | RCT | Women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Split pea | Beans (white, red, and wax) | Cowpea | ||||

| Mollard et al., 2012 [49] | RCT | Men and women | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Split pea | Navy bean | |||||

| Safaeiyan et al., 2015 [50] | RCT | Women with abdominal obesity | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Split pea | Beans (white, red, and wax) | Cowpea | ||||

| Kazemi et al., 2020 [48] | RCT | Women with PCOS | Mixture | Lentil | Chickpea | Split pea | Beans | |||||

| Wilson et al., 2022 [51] | RCT | Men and women with abdominal obesity | Type | Lentil | ||||||||

| Aslani et al., 2015 [52] | RCT | Men and women with T2DM | Type | Lentil sprout | ||||||||

| Reference | Study Design | Population | Study Outcomes a | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Profile | Blood Pressure | CVD Risk and Mortality | Diabetes | Glycemic Control | MetSyn | Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers | Hormonal Profile | Other | |||||||||||

| Askari et al., 2021 [23] | Cross-sectional | Men | [↓] LDL-C | [↑] HDL-C | [—] TAG | [—] FRS | [—] FBS | ||||||||||||

| Baldeón et al., 2021 [24] | Cross-sectional | Men and women | [—] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [—] TC | [—] TG | [↓] SBP | [↓] DBP | [↓] T2DM | [↓] Incident MetSyn [—] WC | |||||||||

| Papanikolaou et al., 2008 [25] | Cross-sectional | Men and women | [↓] SBP | [↓] WC | |||||||||||||||

| Guo et al., 2020 [28] | Cohort | Men and women | [—] Hypertension | ||||||||||||||||

| Pearce et al., 2021 [26] | Federated meta-analysis | Men and women | [—] Incident T2DM | ||||||||||||||||

| Becerra-Tomás et al., 2018 [27] | Cohort | Men and women with high CVD risk | [↓] Incident T2DM | ||||||||||||||||

| Wennberg et al., 2015 [34] | Cohort | Men and women | [↓] Incident T2DM in women | [↓] Impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose in women | [↑] WC in men | ||||||||||||||

| Liu et al., 2021 [29] | Cohort | Men and women | [↓] Incident CVD [—] Incident cancer | [↓] All-cause mortality [↓] Cancer mortality [—] CVD mortality | |||||||||||||||

| Miller et al., 2017 [30] | Cohort | Men and women | [—] Incident CVD | [↓] All-cause mortality [↓] Non-CVD mortality [—] CVD mortality | |||||||||||||||

| Nouri et al., 2016 [31] | Cohort | Men and women | [↓] Incident CVD events | ||||||||||||||||

| Nouri et al., 2021 [32] | Cohort | Men and women | [↓] Incident CVD events | ||||||||||||||||

| Papandreou et al., 2019 [33] | Cohort | Men and women with high CVD risk | [↓] Cancer mortality [↓] CVD mortality | ||||||||||||||||

| Zahradka et al., 2013 [35] | Before-and-after | Men and women with PAD | [—] LDL-C | [—] TC [↓] Serum cholesterol | [↓] Ankle–brachial index | [—] FBS | |||||||||||||

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2016 [41] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with high T2DM risk | [—] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [—] TC | [—] TAG | [—] SBP | [—] DBP | [—] HbA1c | ||||||||||

| Winham et al., 2007 [42] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with IR | [↓] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [↓] TC | [—] TG | [—] HbA1c | [—] hs-CRP | |||||||||||

| Abeysekara et al., 2012 [36] | Randomized crossover | Men and women | [↓] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [↓] TC | [—] TAG | [—] CRP | ||||||||||||

| Hartman et al., 2010 [37] | Randomized crossover | Men | [↑] Fasting glucose | [↓] CRP | [—] sTNFRI [—] sTNFRII [—] C-peptide | ||||||||||||||

| Saraf-Bank et al., 2015 [40] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with high T2DM risk | [—] FBS | [↓] hs-CRP | [—] IL-6 [—] TNF-α [—] Adiponectin | ||||||||||||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 (a) [44] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | [↓] hs-CRP | [↓] IL-6 [↓] TNF)-α | |||||||||||||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2015 (b) [45] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | [↓] LDL-C | [—] TC | [↓] TG | [—] SBP | [—] DBP | [↓] Fasting glucose [↓] Fasting insulin | |||||||||||

| Hosseinpour-Niazi et al., 2022 [46] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | [—] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [—] TC | [—] TG | [↓] SBP | [—] DBP | |||||||||||

| Alizadeh et al., 2014 [47] | RCT | Women | [—] LDL-C | [—] HDL-C | [—] TG | [↓] SBP | [—] DBP | [—] FBS [↑] HOMA-IR | [↓] WC | [↓] ALT [↓] AST | |||||||||

| Mollard et al., 2012 [49] | RCT | Men and women | [—] LDL-C | [↑] HDL-C | [—] TC | [—] TAG | [↓] SBP | [—] DBP | [↓] HbA1c | [↓] WC | [—] Adiponectin | [↑] C-peptide [—] Leptin [—] Ghrelin [—] GLP-1 | |||||||

| Safaeiyan et al., 2015 [50] | RCT | Women with abdominal obesity | [—] LDL-C | [—] TC | [—] NO [—] MDA | [↓] hs-CRP | [↑] TAC [—] Nitrite/nitrate | ||||||||||||

| Wilson et al., 2022 [51] | RCT | Men and women with abdominal obesity | [—] LDL | [—] HDL | [—] TC | [—] TG | [↓] HOMA-IR [—] Peripheral IR | ||||||||||||

| Aslani et al., 2015 [52] | RCT | Men and women with T2DM | [—] LDL-C | [↑] HDL-C | [—] TC | [↓] TG | [↓] ox-LDL | ||||||||||||

| Kazemi et al., 2020 [48] | RCT | Women with PCOS | [↑] HRQoL | ||||||||||||||||

| Mirmiran et al., 2018 [38] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | [↓] Serum MDA [↓] Serum ox-LDL [↑] Serum NO [↑] CAT activity | ||||||||||||||||

| Mirmiran et al., 2019 [39] | Randomized crossover | Men and women with T2DM | [↑] Adiponectin | [—] Leptin | |||||||||||||||

| Zhang et al., 2011 [43] | Randomized crossover | Men | [↓] Leptin [—] Ghrelin | ||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, N.; Jiao, K.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Wallace, T.C. Pulse Consumption and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101435

Zhao N, Jiao K, Chiu Y-H, Wallace TC. Pulse Consumption and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(10):1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101435

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Naisi, Keyi Jiao, Yu-Hsiang Chiu, and Taylor C. Wallace. 2024. "Pulse Consumption and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 16, no. 10: 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101435

APA StyleZhao, N., Jiao, K., Chiu, Y.-H., & Wallace, T. C. (2024). Pulse Consumption and Health Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 16(10), 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16101435