Role of Effective Policy and Screening in Managing Pediatric Nutritional Insecurity as the Most Important Social Determinant of Health Influencing Health Outcomes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Domains | Dimensions | Subdimensions |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Stability | Economic indicators | Income, Assets, Assistance Programs, Indebtedness |

| Employment | Unemployed, Migrant/seasonal, Day laborers, Disability status, Retirement status, Student, Job assistance | |

| Material hardship | Food insecurity, Utilities, Transportation Medication affordability, Access to technology, Childcare, Clothing, Legal services | |

| Education Access and Quality | Education | Educational attainment, Basic literacy, Health literacy, Numeracy |

| Language | Primary language, English proficiency, Interpreter/translator needed, other language proficiency | |

| Health Care Access and Quality | Functional status | ADLs, IADLs, Frailty |

| Health behaviors | Alcohol, Drug use, Tobacco, Secondhand smoking, Physical activity, Sexual activity, Safety Diet | |

| Healthcare access | Insurance status, Healthcare affordability, Source of usual care | |

| Mental health | Depression, Anxiety, PTSD, ADD/ADHD, Suicide/Self-harm, Stress, Sleep | |

| Neighborhood and Built Environment | Demographics | Gender/sexual orientation, Place of birth, Race/ethnicity, Refugee status, Justice Involvement |

| Housing | Homelessness, Housing safety, Housing quality, Housing insecurity | |

| Social and Community Context | Culture | Religion/spiritual beliefs, Family culture |

| Family | Marital status, Dependents, Living arrangements | |

| Social support | Community activities, Safe environment, public spaces, Racism, Discrimination, Trust School culture, social isolation | |

| Trauma/violence | IPV, Trauma, Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Mental abuse | |

| Veteran status | Military trauma history, Combat veteran, Active Military |

2. Food Insecurity and Associated Factors

2.1. Food Insecurity

2.2. Food Landscaping

3. Effect of Food Insecurity and Associated Factors on Children

3.1. Development and Transition

3.2. Impact of Family and Social Conditions

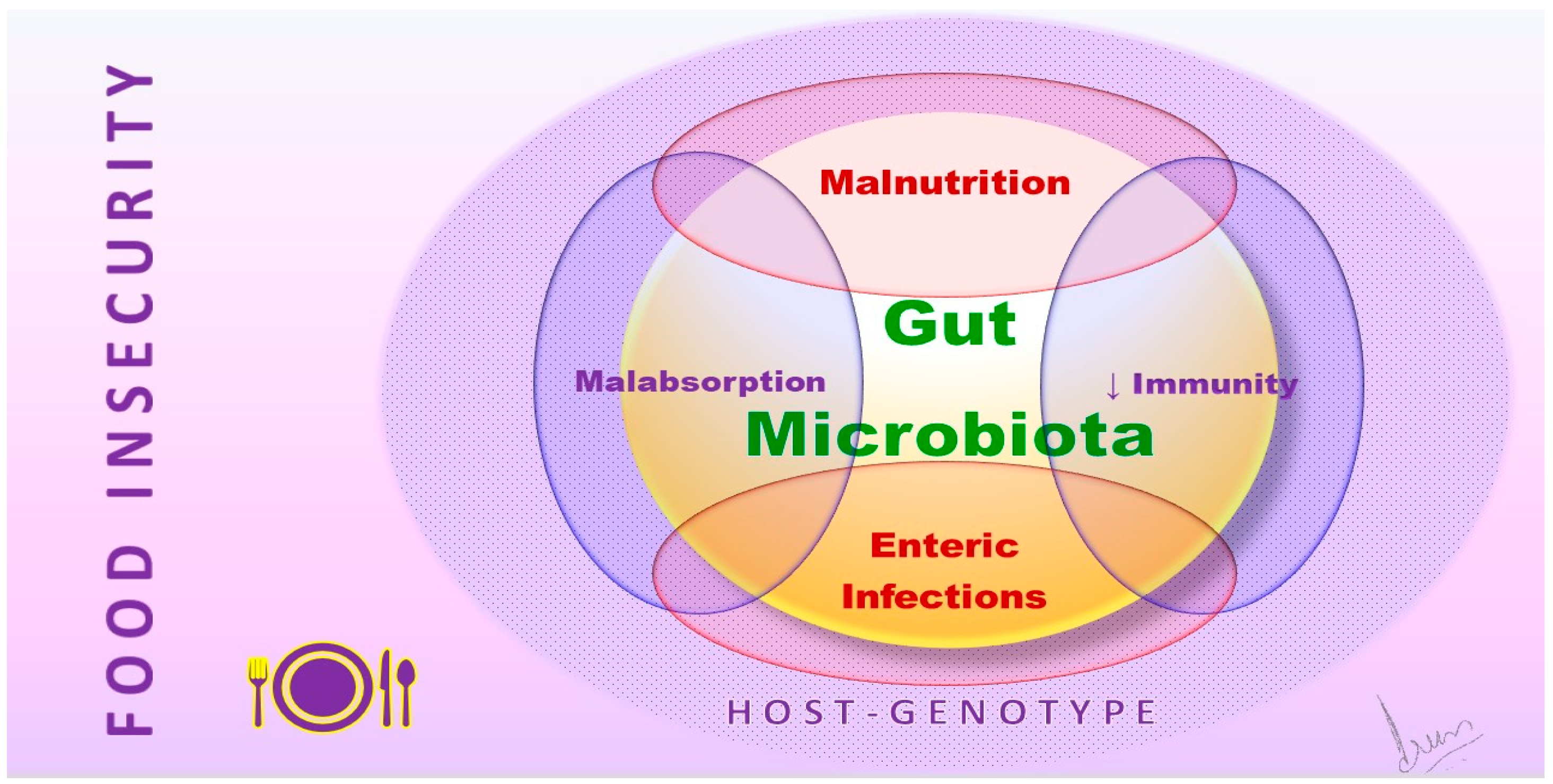

3.3. Impact of Sociobiome

4. SDOH Effect on the Nutrition of Children

4.1. Obesity and Malnutrition

4.2. Gut Microbiota and Nutrition

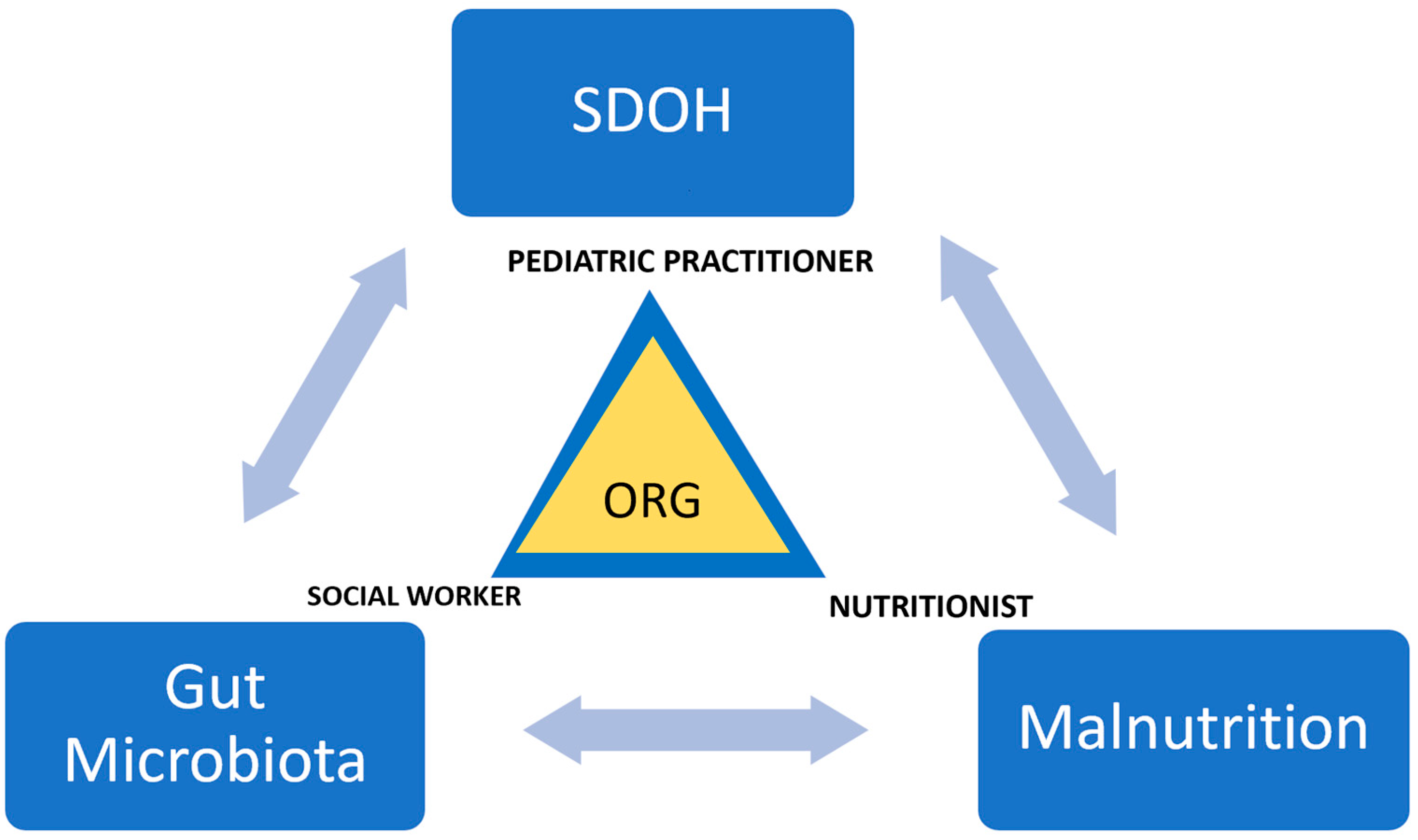

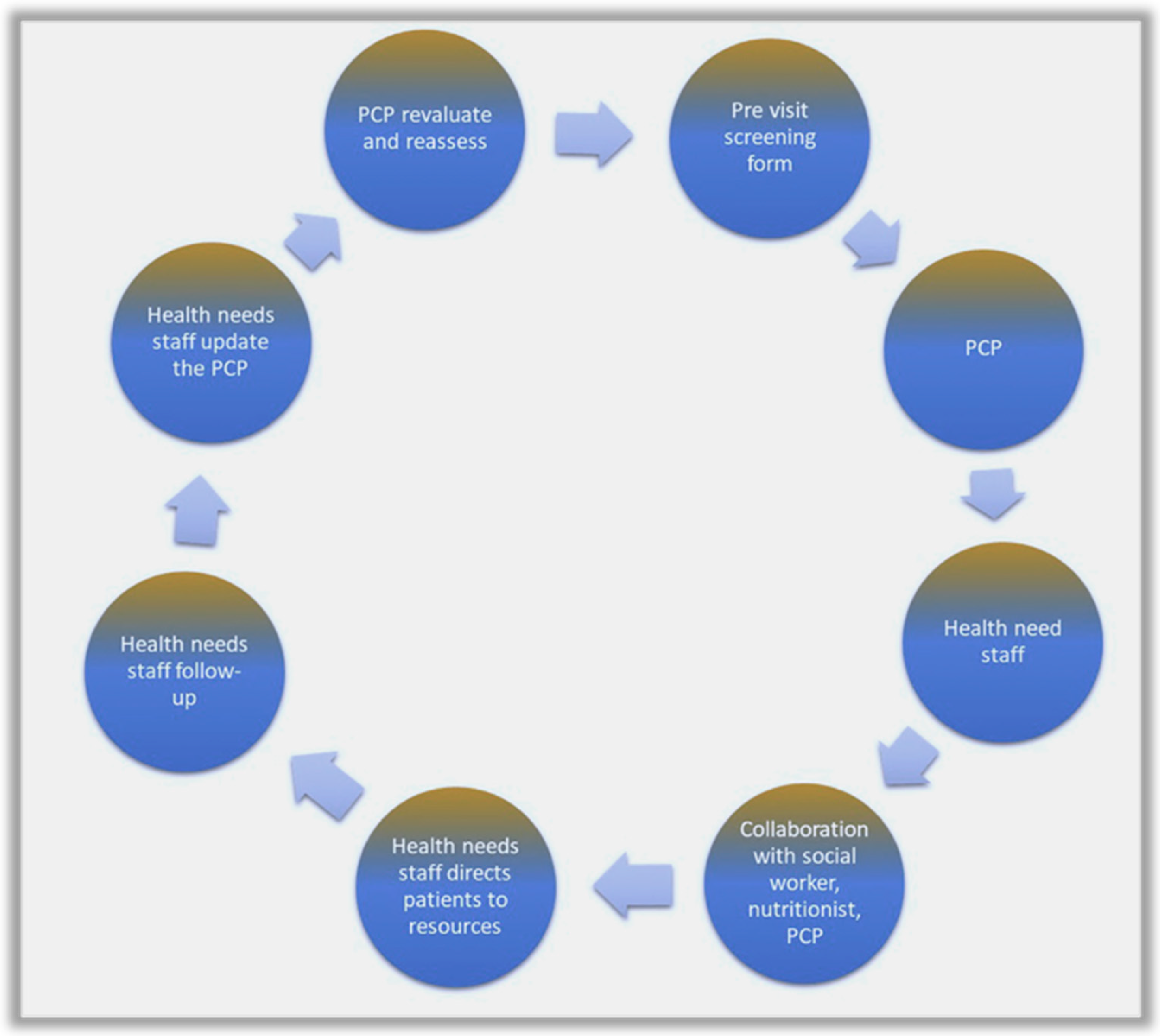

5. Healthcare Workers’ Role in Screening, Liaison, Evaluation, and Management

- Healthcare providers should routinely ask parents general questions to uncover their concerns and needs.

- Identifying any existing risk factors or protective factors is crucial.

- Specific social issues should be systematically screened during regular check-ups.

- Patients and families with identified needs should be referred to professionals in other fields and community organizations that can provide assistance and resources, such as the Medicaid office or legal advocacy groups.

- At the patient level, sensitively inquire about social challenges, refer patients, and assist them in accessing benefits and support services.

- At the practice level, improve access and the quality of care for hard-to-reach patient groups and incorporate patient social support navigators into the primary care team.

- At the community level, collaborate with community organizations, public health entities, and local leaders to create a healthier environment. Physicians can also advocate for social change by leveraging their clinical experience and research evidence, participating in community needs assessment and health planning, and engaging in community empowerment efforts and changing social norms [34].

6. Models and Tools Related to SDOH

7. Intervention Suggestions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Healthy People. Social Determinants of Health 2020. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- AMA. What Are Social Determinants of Health? 2022. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/what-are-social-determinants-health (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Whitman, A.; De Lew, N.; Chappel, A.; Aysola, V.; Zuckerman, R.; Sommers, B.D. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/sdoh-evidence-review (accessed on 12 June 2023).

- Health Research & Educational Trust. Social Determinants of Health Series: Food Insecurity and the Role of Hospitals; American Hospital Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.aha.org/ahahret-guides/2017-06-21-social-determinants-health-series-food-insecurity-and-role-hospitals (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Byhoff, E.; Garg, A.; Pellicer, M.; Diaz, Y.; Yoon, G.H.; Charns, M.P.; Drainoni, M.-L. Provider and Staff Feedback on Screening for Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health for Pediatric Patients. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2019, 32, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Food Security in the U.S. 2022. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/measurement/ (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2021; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=104655 (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Center FRAC. Hunger and Health, The Impact of Poverty, Food Insecurity, and Poor Nutrition on Health and Well-Being. 2017. Available online: https://frac.org/wp-content/uploads/hunger-health-impact-poverty-food-insecurity-health-well-being.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Thompson, C. Dietary health in the context of poverty and uncertainty around the social determinants of health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, H.; Weeks, J.D.; Madans, J.H. Children Living in Households That Experienced Food Insecurity: United States, 2019–2020 CDC2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db432.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Pereira, M.; Oliveira, A.M. Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3236–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group USD. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-impact-covid-19-food-security-and-nutrition (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Chen, T.; Gregg, E. Food Deserts and Food Swamps: A Primer: National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health 2017. Available online: https://www.ncceh.ca/sites/default/files/Food_Deserts_Food_Swamps_Primer_Oct_2017.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Davis, B.; Carpenter, C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honório, O.S.; Pessoa, M.C.; Gratão, L.H.A.; Rocha, L.L.; de Castro, I.R.R.; Canella, D.S.; Horta, P.M.; Mendes, L.L. Social inequalities in the surrounding areas of food deserts and food swamps in a Brazilian metropolis. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz, T.; Pignataro, V.; Bonifazi, D.; Ravera, S.; Mellado, M.J.; Pérez-Martínez, A.; Escudero, A.; Ceci, A.; Calvo, C. Human Microbiome in Children, at the Crossroad of Social Determinants of Health and Personalized Medicine. Children 2021, 8, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C.K. The capacity-load model of non-communicable disease risk: Understanding the effects of child malnutrition, ethnicity and the social determinants of health. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.; Ruiz, M.O.; Rovnaghi, C.R.; Tam, G.K.-Y.; Hiscox, J.; Gotlib, I.H.; Barr, D.A.; Carrion, V.G.; Anand, K.J.S. The social ecology of childhood and early life adversity. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.K.; Siegel, B.S.; Garg, A.; Conroy, K.; Gross, R.S.; Long, D.A.; Lewis, G.; Osman, C.J.; Messito, M.J.; Wade, R., Jr.; et al. Screening for Social Determinants of Health Among Children and Families Living in Poverty: A Guide for Clinicians. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 2016, 46, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.R.; Tyler, J.; Scurrah, K.J.; Reavley, N.J.; Dite, G.S. The Association between Socioeconomic Status and Psychological Distress: A Within and Between Twin Study. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2019, 22, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot, Y.; Reshef, L.; Maya, M.; Cohen, D.; Gophna, U.; Muhsen, K. Socioeconomic disparities and household crowding in association with the fecal microbiome of school-age children. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anda, R. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study: Child Abuse and Public Health 1994. Available online: https://preventchildabuse.org/images/docs/anda_wht_ppr.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Nobre, J.G.; Alpuim Costa, D. “Sociobiome”: How do socioeconomic factors influence gut microbiota and enhance pathology susceptibility?—A mini-review. Front. Gastroenterol. 2022, 1, 1020190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Cai, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, F.; Zheng, C. The Role of Microbiota in Infant Health: From Early Life to Adulthood. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 708472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What Is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.; Bettag, J.; Morfin, S.; Manithody, C.; Nagarapu, A.; Jain, A.; Nazzal, H.; Prem, S.; Unes, M.; McHale, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Modulation of Short Bowel Syndrome and the Gut–Brain Axis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacesa, R.; Kurilshikov, A.; Vich Vila, A.; Sinha, T.; Klaassen, M.A.Y.; Bolte, L.A.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Chen, L.; Collij, V.; Hu, S.; et al. Environmental factors shaping the gut microbiome in a Dutch population. Nature 2022, 604, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, Z.I.; Dongarwar, D.; A Yusuf, R.; Bell, M.; Harris, T.; Salihu, H.M. Social Determinants of Overweight and Obesity Among Children in the United States. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2019, 9, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, M.; Anderson, P. Income and race/ethnicity influence dietary fiber intake and vegetable consumption. Nutr. Res. 2014, 34, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, E.M. The role of gut microbiota in nutritional status. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, A.L.; Ahern, P.P.; Griffin, N.W.; Goodman, A.L.; Gordon, J.I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature 2011, 474, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.K.M.L.; Elo, I.T.; Coyne, J.C.; Culhane, J.F. Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: The influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambul. Pediatr. 2008, 8, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafer, A.; Rosenthal, M.; Smith, P.; McGrew, D.; Bhattacharya, K.; Rong, Y.; Salkar, M.; Yang, J.; Nguyen, J.; Arnold, A. Examining the context, logistics, and outcomes of food prescription programs: A scoping review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 19, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andermann, A. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: A framework for health professionals. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, E474–E483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Low, L.L.; Lu, S.Y.; Lee, C.E. Implementation of social prescribing: Lessons learnt from contextualising an intervention in a community hospital in Singapore. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 35, 100561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; LeBlanc, A.; Raphael, J.L. Inadequacy of Current Screening Measures for Health-Related Social Needs. JAMA 2023, 330, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, A. Development of a Screening Tool for Social Determinants of Health at a Federally Qualified Health Center. Pediatrics 2021, 147, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Jack, B.; Zuckerman, B. Addressing the social determinants of health within the patient-centered medical home: Lessons from pediatrics. JAMA 2013, 309, 2001–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Network SIRaE. Social Needs Screening Tools Comparison Table (Pediatric Settings); University of San Francisco California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://sirenetwork.ucsf.edu/social-needs-screening-tools-comparison-table-pediatric-settings (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Garg, A.; Marino, M.; Vikani, A.R.; Solomon, B.S. Addressing families’ unmet social needs within pediatric primary care: The health leads model. Clin. Pediatr. 2012, 51, 1191–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Dworkin, P.H. Applying surveillance and screening to family psychosocial issues: Implications for the medical home. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2011, 32, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, R.; Strahley, A.; Weiss, J.; McNeill, S.; McBride, A.S.; Best, S.; Harrison, D.; Montez, K. Exploring Perceptions of a Fresh Food Prescription Program during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tools | Basic Description |

|---|---|

| Child Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) | Child Maltreatment—emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect |

| History of Victimization Form | Child maltreatment—sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, witness to family violence, and psychological abuse |

| Kempe Family Stress Inventory | Child Maltreatment—physical, sexual, and/or psychological abuse |

| US Department of Agriculture Household Food Security Module | Family Financial support—Assessing general household and child food security, categorized into high, marginal, low, and very low food security |

| Two-question screen validated for clinical use | Family Financial support—“Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.” “Within the past 12 months, the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.” |

| HITS (Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream) tool | Intimate partner violence, Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS) used as gold standard |

| PVS (Partner Violence Screen) | Intimate partner violence. CTS is used as a gold standard. A positive response to any item represents a positive screen |

| WAST (Women Abuse Screening Tool), WAST-SF (Women Abuse Screening Tool—Short Form | Intimate partner violence |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) | Maternal Depression and Family Mental Illness |

| Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) | Maternal Depression and Family Mental Illness |

| Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) | Household and Substance Abuse, Parent screening questionnaire |

| Survey of Well-Being of Young Children (SWYC) | Household Substance Abuse, Family Questionnaire |

| HEADS (Home, Education & Employment, Activities, Drugs, Sexuality, Suicide/Depression) | Household Substance Abuse |

| CRAFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) | Household Substance Abuse |

| TOFHLA (Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults) | Parental Health Literacy |

| REALM (Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine) REALM-R–shortened, revised version | Patients are asked to read aloud to check for correct pronunciation. |

| AHC—Tool Accountable Health Communities tool AHS HRSN Tools—Accountable Health Communities, Health-Related Screening Tools | identify patient needs that can be addressed through community services in 4 domains (economic stability, social & and community context, neighborhood & and physical environment, and food) |

| Health Leads | Questionnaire assessing needs in 5 domains (economic stability, education, social & and community context, neighborhood & and physical environment, and food). |

| MLP iHELLP | Questionnaire assessing needs across 5 domains (economic stability, education, social & and community context, neighborhood & physical environment, and food). |

| PRAPARE Protocol for Responding to & Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks & Experiences | It measures five domains of social determinants of health (SDOH): Housing status, Language, Employment, Transportation, Stress, Income. |

| WellRx | Questionnaire assessing needs in 4 domains (economic stability, education, neighborhood, physical environment, and food) |

| Your Current Life Situation (YCLS) | Questionnaire assessing needs in 6 domains (economic stability, education, social and community context, health and clinical care, neighborhood and physical environment, and food). |

| We Care | Questionnaire assessing needs in 4 domains (economic stability, education, neighborhood and physical environment, and food). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verma, H.; Verma, A.; Bettag, J.; Kolli, S.; Kurashima, K.; Manithody, C.; Jain, A. Role of Effective Policy and Screening in Managing Pediatric Nutritional Insecurity as the Most Important Social Determinant of Health Influencing Health Outcomes. Nutrients 2024, 16, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010005

Verma H, Verma A, Bettag J, Kolli S, Kurashima K, Manithody C, Jain A. Role of Effective Policy and Screening in Managing Pediatric Nutritional Insecurity as the Most Important Social Determinant of Health Influencing Health Outcomes. Nutrients. 2024; 16(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerma, Hema, Arun Verma, Jeffery Bettag, Sree Kolli, Kento Kurashima, Chandrashekhara Manithody, and Ajay Jain. 2024. "Role of Effective Policy and Screening in Managing Pediatric Nutritional Insecurity as the Most Important Social Determinant of Health Influencing Health Outcomes" Nutrients 16, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010005

APA StyleVerma, H., Verma, A., Bettag, J., Kolli, S., Kurashima, K., Manithody, C., & Jain, A. (2024). Role of Effective Policy and Screening in Managing Pediatric Nutritional Insecurity as the Most Important Social Determinant of Health Influencing Health Outcomes. Nutrients, 16(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010005