Childhood Maltreatment in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Implications for Weight Loss, Depression and Eating Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Anthropometric Measurements

2.2.2. Childhood Maltreatment

2.2.3. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.4. Eating Behavior

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. History of Childhood Maltreatment among Patients Prior to BS

3.3. Changes in Weight

3.4. Changes in Depressive Symptoms

3.5. Changes in Eating Behaviors

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Strengths

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Clinical Implications

6.2. Future Research Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Buchwald, H.; Avidor, Y.; Braunwald, E.; Jensen, M.D.; Pories, W.; Fahrbach, K. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004, 292, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Klem, M.L.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Ji, M.; Burke, L.E. Predictors of weight regain after sleeve gastrectomy: An integrative review. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorwinde, V.; Steenhuis, I.H.; Janssen, I.M.; Monpellier, V.M.; van Stralen, M.M. Definitions of long-term weight regain and their associations with clinical outcomes. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrell, S.; Mahoney, C.T.; Lent, M.; Campbell, L.K.; Wood, G.C.; Still, C. Interpersonal abuse and long-term outcomes following bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Child Maltreatment, Fact Sheet. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Gardner, M.; Thomas, H.; Erskine, H. The association between five forms of child maltreatment and depressive and anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 96, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.; Cannings-John, R.; Hood, K.; Kemp, A.; Robling, M. Establishing the international prevalence of self-reported child maltreatment: A systematic review by maltreatment type and gender. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Abajobir, A.A.; Mills, R.; Strathearn, L.; Clavarino, A.; Najman, J.M. Child maltreatment and mental health problems in adulthood: Birth cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; White, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Rothschild, B.S.; Burke-Martindale, C.H. Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. Obes. Surg. 2006, 16, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, H.L.; Fleming, J.E.; Trocmé, N.; Boyle, M.H.; Wong, M.; Racine, Y.A.; Beardslee, W.R.; Offord, D.R. Prevalence of child physical and sexual abuse in the community: Results from the Ontario Health Supplement. JAMA 1997, 278, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterhänsel, C.; Nagl, M.; Wagner, B.; Dietrich, A.; Kersting, A. Childhood maltreatment in bariatric patients and its association with postoperative weight, depressive, and eating disorder symptoms. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, A.; Tan, M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caslini, M.; Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Dakanalis, A.; Clerici, M.; Carrà, G. Disentangling the association between child abuse and eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2016, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, P.; Ichikawa, L.; Simon, G.E.; Ludman, E.J.; Linde, J.A.; Jeffery, R.W.; Operskalski, B.H. Associations of child sexual and physical abuse with obesity and depression in middle-aged women. Child Abus. Negl. 2008, 32, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, B.; Pfaff, J.J.; Pirkis, J.; Snowdon, J.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Wilson, I.; Almeida, O.P.; Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice Study Group. Long-term effects of childhood abuse on the quality of life and health of older people: Results from the Depression and Early Prevention of Suicide in General Practice Project. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M.; Brody, M.; Toth, C.; Burke-Martindale, C.H.; Rothschild, B.S. Childhood maltreatment in extremely obese male and female bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orcutt, M.; King, W.C.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Devlin, M.J.; Marcus, M.D.; Garcia, L.; Steffen, K.J.; Mitchell, J.E. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and psychopathology in adults undergoing bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Samaan, J.S.; Premkumar, A.; Samakar, K. History of abuse and bariatric surgery outcomes: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 4650–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışır, S.; Çalışır, A.; Arslan, M.; İnanlı, İ.; Çalışkan, A.M.; Eren, İ. Assessment of depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and eating psychopathology after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: 1-year follow-up and comparison with healthy controls. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmelmann, C.L.; Dela, F.; Mortensen, E.L. Psychological predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery: A review of the recent research. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, e299–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colles, S.L.; Dixon, J.B.; O’brien, P.E. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: Two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity 2008, 16, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Marcus, M.D.; Grilo, C.M. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: A prospective, 24-month follow-up study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrice, M.; Paul, K.D. Interventions to improve long-term weight loss in patients following bariatric surgery: Challenges and solutions. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2015, 8, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller-Matero, L.R.; Bryce, K.; Saulino, C.K.; Dykhuis, K.E.; Genaw, J.; Carlin, A.M. Problematic eating behaviors predict outcomes after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 1910–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, N.J.; King, W.C.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Belle, S.H. Validity of self-reported weights following bariatric surgery. JAMA 2013, 310, 2454–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Stein, J.A.; Newcomb, M.D.; Walker, E.; Pogge, D.; Ahluvalia, T.; Stokes, J.; Handelsman, L.; Medrano, M.; Desmond, D.; et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 2003, 27, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.P.; Fink, L.; Handelsman, L.; Foote, J.; Lovejoy, M.; Wenzel, K.; Sapareto, E.; Ruggiero, J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry 1994, 151, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar]

- King, W.C.; Hinerman, A.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Devlin, M.J.; Marcus, M.D.; Mitchell, J.E. The impact of childhood trauma on change in depressive symptoms, eating pathology, and weight after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K.; Thomas, M.L.; Sciolla, A.F.; Schneider, B.; Pappas, K.; Bleijenberg, G.; Bohus, M.; Bekh, B.; Carpenter, L.; Carr, A.; et al. Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential: Results from a large, multinational sample using the childhood trauma questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.; Stoeckel, N.; Napolitano, M.A.; Collins, C.; Wood, G.C.; Seiler, J.; Grunwald, H.E.; Foster, G.D.; Still, C.D. Examination of the Beck Depression Inventory-II factor structure among bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Beck Depression Inventory; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Storch, E.A.; Roberti, J.W.; Roth, D.A. Factor structure, concurrent validity, and internal consistency of the beck depression inventory—Second edition in a sample of college students. Depress. Anxiety 2004, 19, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.; Butt, M.; Rigby, A. Internalized weight bias in patients presenting for bariatric surgery. Eat. Behav. 2020, 39, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.; Bergers, G.P.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akduman, I.; Sevincer, G.M.; Bozkurt, S.; Kandeger, A. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and problematic eating behaviors in bariatric surgery candidates. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevinçer, G.M.; Konuk, N.; İpekçioğlu, D.; Crosby, R.D.; Cao, L.; Coskun, H.; Mitchell, J.E. Association between depression and eating behaviors among bariatric surgery candidates in a Turkish sample. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2017, 22, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildes, J.E.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Marcus, M.D.; Levine, M.D.; Courcoulas, A.P. Childhood maltreatment and psychiatric morbidity in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Surg. 2008, 18, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.A.; Unutzer, J.; Rutter, C.; Gelfand, A.; Saunders, K.; VonKorff, M.; Koss, M.P.; Katon, W. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1999, 56, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz, L.B.; Brito, C.L.; Debon, L.M.; Brandalise, L.N.; Azevedo, J.T.; Monbach, K.D.; Heberle, L.S.; Mottin, C.C. Variation of Binge Eating One Year after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Its Relationship with Excess Weight Loss. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spirou, D.; Raman, J.; Smith, E. Psychological outcomes following surgical and endoscopic bariatric procedures: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, I.; Olschlager, S.; Sauer, H.; von Feilitzsch, M.; Weimer, K.; Junne, F.; Peeraully, R.; Enck, P.; Zipfel, S.; Teufel, M. Does Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Improve Depression, Stress and Eating Behaviour? A 4-Year Follow-up Study. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 2967–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Faulconbridge, L.F.; Jones-Corneille, L.R.; Sarwer, D.B.; Fabricatore, A.N.; Thomas, J.G.; Wilson, G.T.; Alexander, M.G.; Pulcini, M.E.; Webb, V.L.; et al. Binge eating disorder and the outcome of bariatric surgery at one year: A prospective, observational study. Obesity 2011, 19, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porat, T.; Weiss, R.; Sherf-Dagan, S.; Rottenstreich, A.; Kaluti, D.; Khalaileh, A.; Abu Gazala, M.; Ben-Anat, T.Z.; Mintz, Y.; Sakran, N.; et al. Food addiction and binge eating during one year following sleeve gastrectomy: Prevalence and implications for postoperative outcomes. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michopoulos, V.; Powers, A.; Moore, C.; Villarreal, S.; Ressler, K.J.; Bradley, B. The mediating role of emotion dysregulation and depression on the relationship between childhood trauma exposure and emotional eating. Appetite 2015, 91, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperatori, C.; Innamorati, M.; Lamis, D.A.; Farina, B.; Pompili, M.; Contardi, A.; Fabbricatore, M. Childhood trauma in obese and overweight women with food addiction and clinical-level of binge eating. Child Abus. Negl. 2016, 58, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, B.; Tenore, K.; Mancini, F. Early maladaptive schemas in overweight and obesity: A schema mode model. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, N.; Adambekov, S.; Edwards, R.P.; Ramanathan, R.C.; Bovbjerg, D.H.; Linkov, F. Relationships between a history of abuse, changes in body mass index, physical health, and self-reported depression in female bariatric surgery patients. Bariatr. Surg. Pract. Patient Care 2019, 14, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.K.; Geenen, R. Childhood sexual abuse is not associated with a poor outcome after gastric banding for severe obesity. Obes. Surg. 2005, 15, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymowitz, G.; Salwen, J.; Salis, K.L. A mediational model of obesity related disordered eating: The roles of childhood emotional abuse and self-perception. Eat. Behav. 2017, 26, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter † | Total Sample (n = 111) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and medical background (n = 111) | |

| Sex (n (% females)) | 94 (84.7) |

| Age (years) | 45.1 (11.7) |

| Race (n (% White)) | 99 (89.2) |

| Education (years of studies) | 14.0 (11.0–16.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Single (n (%)) | 30 (27.0) |

| Common-law partner (n (%)) | 28 (25.2) |

| Married (n (%)) | 44 (39.6) |

| Divorced/separated (n (%)) | 9 (8.1) |

| Widowed (n (%)) | 0 (0.0) |

| Monthly income | |

| Less than CAD 23,000 (n (%)) | 12 (10.9) |

| CAD 23,001–37,000 (n (%)) | 11 (10.0) |

| CAD 37,001–57,000 (n (%)) | 25 (22.7) |

| CAD 57,001–84,000 (n (%)) | 23 (20.9) |

| More than CAD 84,000 (n (%)) | 29 (26.4) |

| Don’t know/not answered (n (%)) | 11 (9.9) |

| Type 2 diabetes (n (%)) | 25 (22.5) |

| Hypertension (n (%)) | 45 (40.5) |

| High LDL cholesterol (n (%)) | 29 (26.1) |

| Currently seeing psychologist/psychiatrist (n (%)) | 29 (26.1) |

| Weight (kg) | 129.0 (110.0–144.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 46.7 (42.4–51.9) |

| Smoking status (n, (%yes)) | 11 (9.9) |

| History of childhood maltreatment based on CTQ scores (n = 111) | |

| Total CTQ score | 38.0 (31.0–54.5) |

| Emotional abuse (scale score) | 8.0 (6.0–12.0) |

| Physical abuse (scale score) | 5.0 (5.0–7.5) |

| Emotional neglect (scale score) | 10.0 (7–15) |

| Physical neglect (scale score) | 7.0 (5.0–9.0) |

| Sexual abuse (scale score) | 5.0 (5.0–8.0) |

| Eating behavior based on DEBQ scores (n = 79) | |

| DEBQ restrained eating scale | 29.0 (24.0–31.5) |

| DEBQ emotional eating scale | 39.0 (12.9) |

| DEBQ external eating scale | 24.0 (5.3) |

| Depressive symptoms based on BDI-II scores (n = 85) | |

| BDI-II total score | 14.0 (8.0–21.0) |

| 1 Symptomology classifications | |

| Minimal depression (n (%)) | 39 (45.9) |

| Mild depression (n (%)) | 21 (24.7) |

| Moderate depression (n (%)) | 16 (18.8) |

| Severe depression (n (%)) | 9 (10.6) |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Parameter † | Non-EA n = 58 | EA n = 53 | p-Value | Non-PA n = 83 | PA n = 28 | p-Value | Non-EN n = 54 | EN n = 57 | p-Value | |||

| Age (years) | 45.4 (11.7) | 44.9 (11.7) | 0.849 | 44.0 (12.1) | 48.5 (9.8) | 0.078 | 45.7 (11.7) | 44.6 (44.7) | 0.601 | |||

| Education (years of studies) | 14.0 (11.0–16.0) | 14.0 (11.0–15.0) | 0.445 | 14.0 (11.0–16.0) | 13.5 (11.0–16.0) | 0.880 | 14.0 (11.0–15.0) | 14.0 (11.0–16.0) | 0.922 | |||

| Marital status Single (n (%)) Common-law partner (n (%)) Married (n (%)) Divorced/separated (n (%)) Widowed (n (%)) | 15 (25.9) 13 (22.4) 26 (44.8) 4 (6.9) 0 (0.0) | 15 (2.8) 15 (2.8) 18 (34.0) 5 (9.4) 0 (0.0) | 0.685 | 25 (30.1) 21 (25.3) 31 (37.3) 6 (7.2) 0 (0.0) | 5 (17.9) 7 (25.0) 13 (46.4) 3 (10.7) 0 (0.0) | 0.590 | 12 (22.2) 14 (25.9) 23 (42.6) 5 (9.3) 0 (0.0) | 18 (31.6) 14 (24.6) 21 (36.8) 4 (7.0) 0 (0.0) | 0.724 | |||

| Monthly income Less than CAD 23,000 (n (%)) CAD 23,001–37,000 (n (%)) CAD 37,001–57,000 (n (%)) CAD 57,001–84,000 (n (%)) More than CAD 84,000 (n (%)) DK/not answered (n (%)) | 5 (8.6) 7 (12.1) 10 (17.2) 15 (25.9) 14 (24.1) 7 (12.1) | 7 (13.2) 4 (7.5) 15 (28.3) 8 (15.1) 15 (28.3) 4 (7.5) | 0.244 | 10 (12.0) 8 (9.6) 18 (21.7) 19 (22.9) 21 (25.3) 7 (8.4) | 2 (7.1) 3 (10.7) 7 (25.0) 4 (14.3) 8 (28.6) 4 (14.3) | 0.954 | 6 (11.1) 6 (11.1) 10 (18.5) 15 (27.8) 14 (25.9) 3 (5.6) | 6 (10.7) 5 (8.9) 15 (26.8) 8 (14.3) 15 (26.8) 8 (14.0) | 0.564 | |||

| Weight (kg) | 123.2 (109.2–140.6) | 132.0 (116.6–148.3) | 0.035 | 130.3 (115.2–144.5) | 121.6 (108.9–144.0) | 0.356 | 124.0 (107.0–143.0) | 132 (119.0–145.0) | 0.084 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 45.2 (42.4–49.5) | 48.8 (43.5–53.7) | 0.023 | 46.9 (42.6–51.9) | 45.7 (41.2–45.7) | 0.658 | 45.8 (42.1–49.6) | 48.6 (43.4–52.8) | 0.081 | |||

| Smoking status (n, (yes%)) | 4 (6.9) | 7 (13.2) | 0.266 | 7 (8.4) | 4 (14.3) | 0.370 | 5 (9.3) | 6 (10.5) | 0.823 | |||

| 2 DEBQ restrained eating | 29.0 (24.5–30.0) | 29.0 (24.0–34.3) | 0.362 | 29.0 (24.5–31.5) | 28.0 (23.8–32.5) | 0.972 | 29.0 (25.0–30.0) | 28.0 (23.8–34.0) | 0.739 | |||

| 2 DEBQ emotional eating | 37.8 (13.5) | 40.6 (12.2) | 0.342 | 39.2 (12.8) | 38.1 (13.8) | 0.742 | 37.0 (12.0) | 41.2 (13.8) | 0.150 | |||

| 2 DEBQ external eating | 31.5 (4.9) | 32.4 (5.9) | 0.461 | 32.2 (5.4) | 30.7 (5.2) | 0.312 | 30.8 (4.8) | 33.1 (5.7) | 0.036 | |||

| 1 BDI-II total score | 11.0 (7.0–17.0) | 17.0 (10.8–25.3) | 0.012 | 13.0 (8.0–20.0) | 19.0 (11.8–22.5) | 0.224 | 10.0 (6.0–17.0) | 18.0 (13.8–24.3) | 0.002 | |||

| 1,3 Depression classification 1,3 Minimal (n (%)) 1,3 Mild (n (%)) 1,3 Moderate (n (%)) 1,3 Severe (n (%)) | 28 (57.1) 12 (24.5) 6 (12.2) 3 (6.1) | 11 (30.6) 9 (25.0) 10 (27.8) 6 (16.7) | 0.017 | 35 (50.7) 16 (23.2) 12 (17.4) 6 (8.7) | 4 (25.0) 5 (31.3) 4 (25.0) 3 (18.8) | 0.026 | 29 (64.4) 7 (15.6) 6 (13.3) 3 (6.7) | 10 (25.0) 14 (35.0) 10 (25.0) 6 (15.0) | 0.004 | |||

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Parameter † | Non-PN n = 66 | PN n = 45 | p-Value | Non-SA n = 67 | SA n = 44 | p-Value | ||||||

| Age (years) | 45.6 (11.3) | 44.4 (12.3) | 0.602 | 44.2 (10.9) | 46.5 (12.7) | 0.314 | ||||||

| Education (years of studies) | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 13.0 (11.0–15.0) | 0.104 | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 13.0 (11.0–15.0) | 0.057 | ||||||

| Marital status Single (n (%)) Common-law partner (n (%)) Married (n (%)) Divorced/separated (n (%)) Widowed (n (%)) | 18 (27.2) 20 (30.3) 24 (36.4) 4 (6.1) 0 (0.0) | 12 (26.7) 8 (17.8) 20 (44.4) 5 (11.1) 0 (0.0) | 0.399 | 17 (25.4) 13 (19.4) 31 (46.3) 6 (9.0) 0 (0.0) | 13 (29.5) 15 (34.1) 13 (29.5) 3 (6.8) 0 (0.0) | 0.215 | ||||||

| Monthly income Less than CAD 23 000 (n (%)) CAD 23 001–37 000 (n (%)) CAD 37 001–57 000 (n (%)) CAD 57 001–84 000 (n (%)) More than CAD 84 000 (n (%)) DK/not answered (n (%)) | 8 (12.1) 6 (9.1) 13 (19.7) 15 (22.7) 20 (30.3) 4 (6.1) | 4 (8.9) 5 (11.1) 12 (26.7) 8 (17.8) 9 (20.0) 7 (15.6) | 0.429 | 6 (9.1) 7 (10.6) 11 (16.7) 12 (18.2) 23 (34.8) 8 (11.9) | 6 (13.6) 4 (9.1) 14 (31.8) 11 (25.0) 6 (13.6) 3 (6.8) | 0.188 | ||||||

| Weight (kg) | 124.5 (109.7–144.4) | 131.5 (118.8–144.2) | 0.385 | 131.0 (115.0–149.0) | 126.0 (109.0–136.0) | 0.112 | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 45.8 (42.4–50.8) | 48.8 (42.4–52.7) | 0.246 | 46.8 (42.4–52.8) | 46.5 (42.3–50.3) | 0.544 | ||||||

| Smoking status (n, (yes%)) | 5 (7.6) | 6 (13.3) | 0.319 | 8 (11.9) | 3 (6.8) | 0.377 | ||||||

| 2 DEBQ restrained eating | 29.0 (26.0–31.0) | 26.5 (22.3–32.3) | 0.183 | 28.0 (24.0–30.0) | 30.0 (25.0–34.0) | 0.251 | ||||||

| 2 DEBQ emotional eating | 37.8 (12.7) | 41.1 (13.4) | 0.264 | 35.7 (12.8) | 44.1 (11.7) | 0.004 | ||||||

| 2 DEBQ external eating | 31.4 (5.8) | 32.7 (4.4) | 0.269 | 31.3 (5.3) | 32.9 (5.2) | 0.173 | ||||||

| 1 BDI-II total score | 12.0 (6.25–21.0) | 15.0 (10.5–20.0) | 0.128 | 13.0 (8.0–19.0) | 16.0 (10.0–24.3) | 0.226 | ||||||

| 1,3 Depression classification 1,3 Minimal (n (%)) 1,3 Mild (n (%)) 1,3 Moderate (n (%)) 1,3 Severe (n (%)) | 28 (51.2) 10 (18.5) 12 (22.2) 4 (7.4) | 11 (35.5) 11 (35.5) 4 (12.9) 5 (16.1) | 0.090 | 27 (50.9) 14 (26.4) 8 (15.1) 4 (7.5) | 12 (37.5) 7 (21.9) 8 (25.0) 5 (15.6) | 0.359 | ||||||

| 1 Outcome Variable † | Group | Baseline Mean (SE) [95% CI] | 6 M Mean (SE) [95% CI] | 12 M Mean (SE) [95% CI] | Main Effect Time | Main Effect Group | Time×Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | F | p | F | p | F | |||||

| Non-EA (n = 58) compared to EA (n = 53) based on CTQ at baseline | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-EA | 46.1 (1.6) [43.1–49.2] | 34.2 (1.6) [31.1–37.3] | 31.9 (1.6) [28.8–35.1] | <0.001 | 528.70 | 0.083 | 3.07 | 0.105 | 2.28 |

| EA | 49.2 (1.5) [46.2–52.3] | 35.5 (1.5) [32.5–38.6] | 33.2 (1.6) [30.1–36.4] | |||||||

| EWL (%) | Non-EA | - | 60.2 (5.6) [49.1–71.3] | 70.7 (5.7) [59.5–82.0] | <0.001 | 35.00 | 0.820 | 0.05 | 0.808 | 0.06 |

| EA | 60.7 (5.5) [49.8–71.6] | 72.1 (5.7) [60.8–83.4] | ||||||||

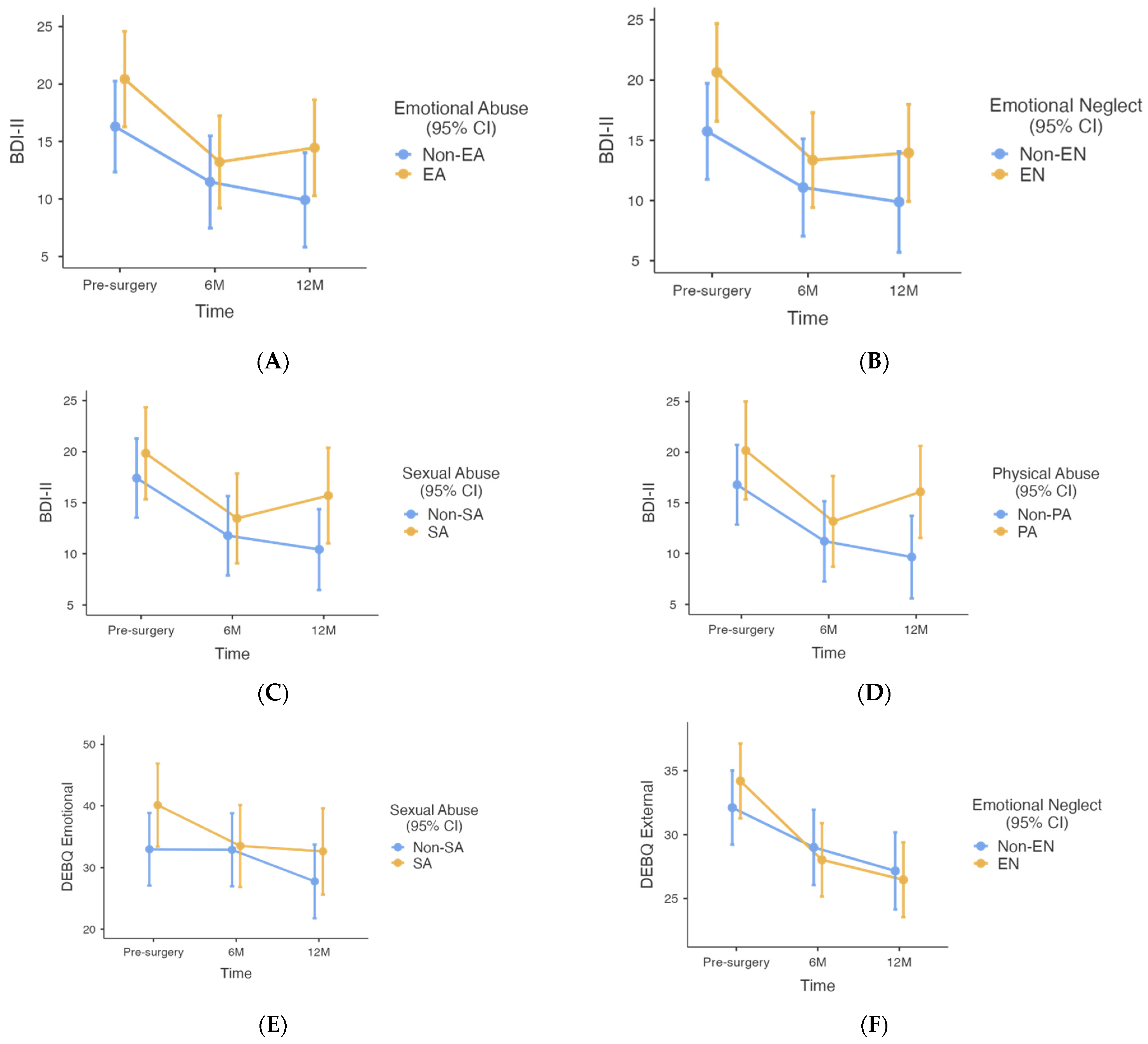

| Total BDI-II score | Non-EA | 16.3 (2.0) [12.3–20.3] | 11.5 (2.0) [7.5–15.5] | 9.9 (2.0) [5.8–14.0] | <0.001 | 32.33 | 0.018 | 5.81 | 0.219 | 1.53 |

| EA | 20.4 (2.1) [16.3–24.6] | 13.2 (2.0) [9.2–17.2] | 14.5 (2.1) [10.3–18.6] | |||||||

| DEBQ restrained eating | Non-EA | 27.6 (2.0) [23.6–31.5] | 32.3 (2.0) [28.2–36.3] | 31.9 (2.1) [27.7–36.1] | 0.003 | 6.27 | 0.492 | 0.47 | 0.090 | 2.46 |

| EA | 29.1 (2.1) [24.9–33.3] | 31.0 (2.1) [26.9–35.2] | 28.8 (2.3) [24.3–33.3] | |||||||

| DEBQ emotional eating | Non-EA | 35.4 (3.1) [29.2–41.6] | 34.2 (3.2) [28.0–40.5] | 29.0 (3.2) [22.6–35.3] | <0.001 | 11.65 | 0.718 | 0.13 | 0.317 | 1.16 |

| EA | 35.5 (3.2) [29.1–42.0] | 31.2 (3.2) [24.9–37.5] | 29.4 (3.3) [22.9–35.8] | |||||||

| DEBQ external eating | Non-EA | 32.9 (1.4) [30.1–35.8] | 29.4 (1.5) [26.5–32.3] | 27.3 (1.5) [24.3–30.2] | <0.001 | 59.43 | 0.341 | 0.91 | 0.130 | 2.07 |

| EA | 33.1 (1.5) [30.2–36.1] | 27.3 (1.5) [24.5–30.2] | 26.2 (1.5) [23.2–29.1] | |||||||

| Non-EN (n = 54) compared to EN (n = 57) based on CTQ at baseline | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-EN | 46.8 (1.6) [43.6–49.9] | 34.8 (1.6) [31.6–37.9] | 32.4 (1.6) [29.2–35.6] | <0.001 | 523.73 | 0.440 | 0.60 | 0.202 | 1.62 |

| EN | 48.6 (1.6) [45.5–51.7] | 35.0 (1.6) [31.2–38.1] | 32.9 (1.6) [29.7–36.0] | |||||||

| EWL (%) | Non-EN | - | 59.9 (5.6) [48.7–71.1] | 72.2 (5.8) [60.8–83.6] | <0.001 | 34.76 | 0.971 | 0.01 | 0.448 | 0.58 |

| EN | 61.2 (5.5) [50.3–72.0] | 70.7 (5.6) [59.9–81.7] | ||||||||

| Total BDI-II score | Non-EN | 15.7 (2.0) [11.8–19.7] | 11.1 (2.0) [7.0–15.1] | 9.9 (2.0) [5.7–14.1] | <0.001 | 33.07 | 0.009 | 7.08 | 0.283 | 1.28 |

| EN | 20.6 (2.0) [16.6–24.7] | 13.4 (2.0) [9.4–17.3] | 14.0 (2.0) [9.9–18.0] | |||||||

| DEBQ restrained eating | Non-EN | 28.2 (2.0) [24.0–31.9] | 32.4 (2.1) [28.3–36.5] | 31.2 (2.2) [26.9–35.5] | 0.001 | 6.92 | 0.576 | 0.32 | 0.536 | 0.63 |

| EN | 28.4 (2.1) [24.2–32.6] | 30.9 (2.1) [26.8–35.0] | 30.0 (2.2) [25.6–34.3] | |||||||

| DEBQ emotional eating | Non-EN | 34.5 (3.2) [28.2–40.8] | 34.1 (3.2) [27.7–40.5] | 29.3 (3.3) [22.8–35.9] | <0.001 | 12.46 | 0.975 | 0.00 | 0.169 | 1.80 |

| EN | 36.7 (3.2) [30.4–43.1] | 31.8 (3.1) [25.6–38.0] | 29.1 (3.2) [22.8–35.4] | |||||||

| DEBQ external eating | Non-EN | 32.1 (1.5) [29.2–35.0] | 29.0 (1.5) [26.1–31.9] | 27.2 (1.5) [24.1–30.2] | <0.001 | 63.33 | 0.895 | 0.02 | 0.013 | 4.52 |

| EN | 34.2 (1.5) [31.3–37.1] | 28.0 (1.4) [25.2–30.9] | 26.5 (1.5) [23.5–29.4] | |||||||

| Non-SA (n = 67) compared to SA (n = 44) based on CTQ at baseline | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-SA | 47.9 (1.5) [45.0–50.9] | 35.0 (1.5) [32.0–38.0] | 32.3 (1.5) [29.3–35.4] | <0.001 | 467.86 | 0.969 | 0.01 | 0.311 | 1.18 |

| SA | 47.2 (1.7) [43.8–50.5] | 34.7 (1.7) [31.3–38.0] | 33.3 (1.8) [29.8–36.8] | |||||||

| EWL (%) | Non-SA | - | 59.6 (5.3) [49.1–70.1] | 72.6 (5.4) [62.0–83.3] | <0.001 | 26.62 | 0.962 | 0.00 | 0.120 | 2.47 |

| SA | 62.5 (6.0) [50.5–74.4] | 69.4 (6.2) [57.0–81.8] | ||||||||

| Total BDI-II score | Non-SA | 17.4 (2.0) [13.5–21.3] | 11.8 (2.0) [7.9–15.7] | 10.4 (2.0) [16.5–14.4] | <0.001 | 28.93 | 0.049 | 3.96 | 0.165 | 1.83 |

| SA | 19.8 (2.3) [15.3–24.3] | 13.5 (2.0) [9.1–17.9] | 15.7 (2.4) [11.0–20.4] | |||||||

| DEBQ restrained eating | Non-SA | 27.5 (2.0) [23.6–31.4] | 31.4 (2.0) [27.5–35.3] | 31.0 (2.1) [26.9–35.1] | 0.004 | 5.75 | 0.685 | 0.17 | 0.423 | 0.87 |

| SA | 29.5 (2.3) [25.0–34.0] | 32.2 (2.2) [27.8–36.6] | 30.0 (2.4) [25.2–34.9] | |||||||

| DEBQ emotional eating | Non-SA | 33.0 (3.0) [27.1–38.9] | 32.9 (3.0) [27.1–38.8] | 27.8 (3.0) [21.8–33.7] | <0.001 | 11.78 | 0.083 | 3.07 | 0.026 | 3.76 |

| SA | 40.1 (3.4) [33.4–46.9] | 33.5 (3.4) [26.9–40.2] | 32.6 (3.5) [25.6–39.6] | |||||||

| DEBQ external eating | Non-SA | 32.4 (1.4) [29.6–35.1] | 28.5 (1.4) [25.7–31.3] | 26.3 (1.4) [23.5–29.1] | <0.001 | 54.49 | 0.410 | 0.69 | 0.235 | 1.46 |

| SA | 34.0 (1.6) [30.8–37.2] | 28.3 (1.6) [25.2–31.4] | 27.7 (1.7) [24.3–31.0] | |||||||

| Non-PN (n = 66) compared to PN (n = 45) based on CTQ at baseline | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-PN | 47.7 (1.6) [44.6–50.9] | 35.4 (1.6) [32.2–38.6] | 33.1 (1.6) [29.9–36.3] | <0.001 | 494.19 | 0.615 | 0.25 | 0.457 | 0.79 |

| PN | 47.9 (1.6) [44.8–51.0] | 34.4 (1.6) [31.3–37.5] | 32.2 (1.6) [28.9–35.4] | |||||||

| EWL (%) | Non-PN | - | 57.6 (5.6) [46.5–68.7] | 69.6 (5.7) [61.2–84.0] | <0.001 | 29.54 | 0.294 | 1.11 | 0.463 | 0.55 |

| PN | 63.5 (5.6) [52.5–74.5] | 72.6 (5.7) [61.2–84.0] | ||||||||

| Total BDI-II score | Non-PN | 17.6 (2.0) [13.5–21.7] | 11.5 (2.0) [7.4–15.7] | 11.3 (2.0) [7.1–15.5] | <0.001 | 26.13 | 0.402 | 0.71 | 0.956 | 0.05 |

| PN | 18.5 (2.0) [14.2–22.8] | 13.0 (2.0) [8.8–17.2] | 12.8 (2.0) [8.3–17.2] | |||||||

| DEBQ restrained eating | Non-PN | 28.9 (2.0) [24.8–32.9] | 32.5 (2.1) [28.4–36.6] | 32.1 (2.2) [27.9–36.4] | 0.003 | 5.98 | 0.185 | 1.78 | 0.432 | 0.84 |

| PN | 28.1 (2.2) [23.9–32.4] | 31.3 (2.1) [27.2–35.3] | 28.5 (2.3) [23.9–33.0] | |||||||

| DEBQ emotional eating | Non-PN | 34.3 (3.2) [28.0–40.5] | 31.5 (3.2) [25.2–37.8] | 28.2 (3.2) [21.8–34.6] | <0.001 | 10.14 | 0.396 | 0.73 | 0.946 | 0.06 |

| PN | 36.4 (3.3) [29.9–42.9] | 33.9 (3.2) [27.6–40.2] | 29.7 (3.4) [23.0–36.4] | |||||||

| DEBQ external eating | Non-PN | 32.8 (1.5) [29.9–35.7] | 28.8 (1.5) [25.8–31.7] | 26.9 (1.5) [23.9–29.8] | <0.001 | 53.67 | 0.853 | 0.03 | 0.443 | 0.81 |

| PN | 33.4 (1.5) [30.4–36.4] | 27.9 (1.5) [25.0–31.8] | 26.5 (1.6) [23.4–29.7] | |||||||

| Non-PA (n = 83) compared to PA (n = 28) based on CTQ at baseline | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Non-PA | 47.7 (1.6) [44.7–50.8] | 35.1 (1.6) [32.0–38.2] | 32.7 (1.6) [29.6–35.8] | <0.001 | 403.01 | 0.867 | 0.03 | 0.858 | 0.15 |

| PA | 47.7 (1.7) [44.4–51.1] | 34.5 (1.7) [31.1–37.9] | 32.7 (1.7) [29.2–36.1] | |||||||

| EWL (%) | Non-PA | - | 59.3 (5.4) [48.5–70.1] | 70.7 (5.6) [59.7–81.7] | <0.001 | 27.65 | 0.598 | 0.28 | 0.717 | 0.13 |

| PA | 62.6 (6.0) [50.6–74.5] | 472.4 (6.1) [60.3–84.5] | ||||||||

| Total BDI-II score | Non-PA | 16.7 (2.0) [12.9–20.7] | 11.2 (2.0) [7.3–15.2] | 9.7 (2.0) [5.6–13.7] | <0.001 | 20.93 | 0.025 | 5.16 | 0.083 | 2.54 |

| PA | 20.2 (2.4) [15.3–20.5] | 13.2 (2.3) [13.7–17.6] | 16.1 (2.3) [11.5–20.6] | |||||||

| DEBQ restrained eating | Non-PA | 28.0 (2.0) [24.2–31.9] | 31.1 (2.0) [27.2–35.0] | 30.6 (2.1) [26.5–34.6] | 0.004 | 5.69 | 0.768 | 0.09 | 0.623 | 0.47 |

| PA | 27.9 (2.5) [23.0–32.9] | 32.9 (2.4) [28.2–37.7] | 30.2 (2.5) [25.3–35.2] | |||||||

| DEBQ emotional eating | Non-PA | 36.1 (3.1) [30.0–42.1] | 34.3 (3.1) [28.2–40.4] | 30.3 (3.1) [24.1–36.5] | <0.001 | 10.66 | 0.330 | 0.96 | 0.410 | 0.90 |

| PA | 35.5 (3.6) [28.3–42.6] | 29.7 (3.5) [22.7–36.7] | 27.6 (3.6) [20.5–34.6] | |||||||

| DEBQ external eating | Non-PA | 33.6 (1.4) [30.8–36.4] | 29.3 (1.4) [26.5–32.1] | 27.5 (1.4) [24.7–30.4] | <0.001 | 43.19 | 0.098 | 2.80 | 0.673 | 0.40 |

| PA | 32.2 (1.7) [28.8–35.5] | 26.7 (1.6) [23.5–29.8] | 25.5 (1.6) [22.3–28.8] | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben-Porat, T.; Bacon, S.L.; Woods, R.; Fortin, A.; Lavoie, K.L., on behalf of the REBORN Study Team. Childhood Maltreatment in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Implications for Weight Loss, Depression and Eating Behavior. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092046

Ben-Porat T, Bacon SL, Woods R, Fortin A, Lavoie KL on behalf of the REBORN Study Team. Childhood Maltreatment in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Implications for Weight Loss, Depression and Eating Behavior. Nutrients. 2023; 15(9):2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092046

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen-Porat, Tair, Simon L. Bacon, Robbie Woods, Annabelle Fortin, and Kim L. Lavoie on behalf of the REBORN Study Team. 2023. "Childhood Maltreatment in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Implications for Weight Loss, Depression and Eating Behavior" Nutrients 15, no. 9: 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092046

APA StyleBen-Porat, T., Bacon, S. L., Woods, R., Fortin, A., & Lavoie, K. L., on behalf of the REBORN Study Team. (2023). Childhood Maltreatment in Patients Undergoing Bariatric Surgery: Implications for Weight Loss, Depression and Eating Behavior. Nutrients, 15(9), 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15092046