Assessment of Nutritional Status and Health Perception among Male Inmates in Israeli Prisons

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Sampling

2.2. Questionnaires

2.3. Dependent Variables

2.4. Independent Variables

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

2.6. Sociodemographic and Imprisonment Characteristics

2.7. Weight Change in Prison and SHS

2.8. Participants’ Weight Status

2.8.1. Differences in Weight Change Based on Environmental, Emotional, Imprisonment, Socio-Demographic, and Weight Characteristics

2.8.2. Prediction of Weight Change in Prison and SHS

2.9. Power Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Imprisonment Characteristics

3.2. Eating Behavior Score

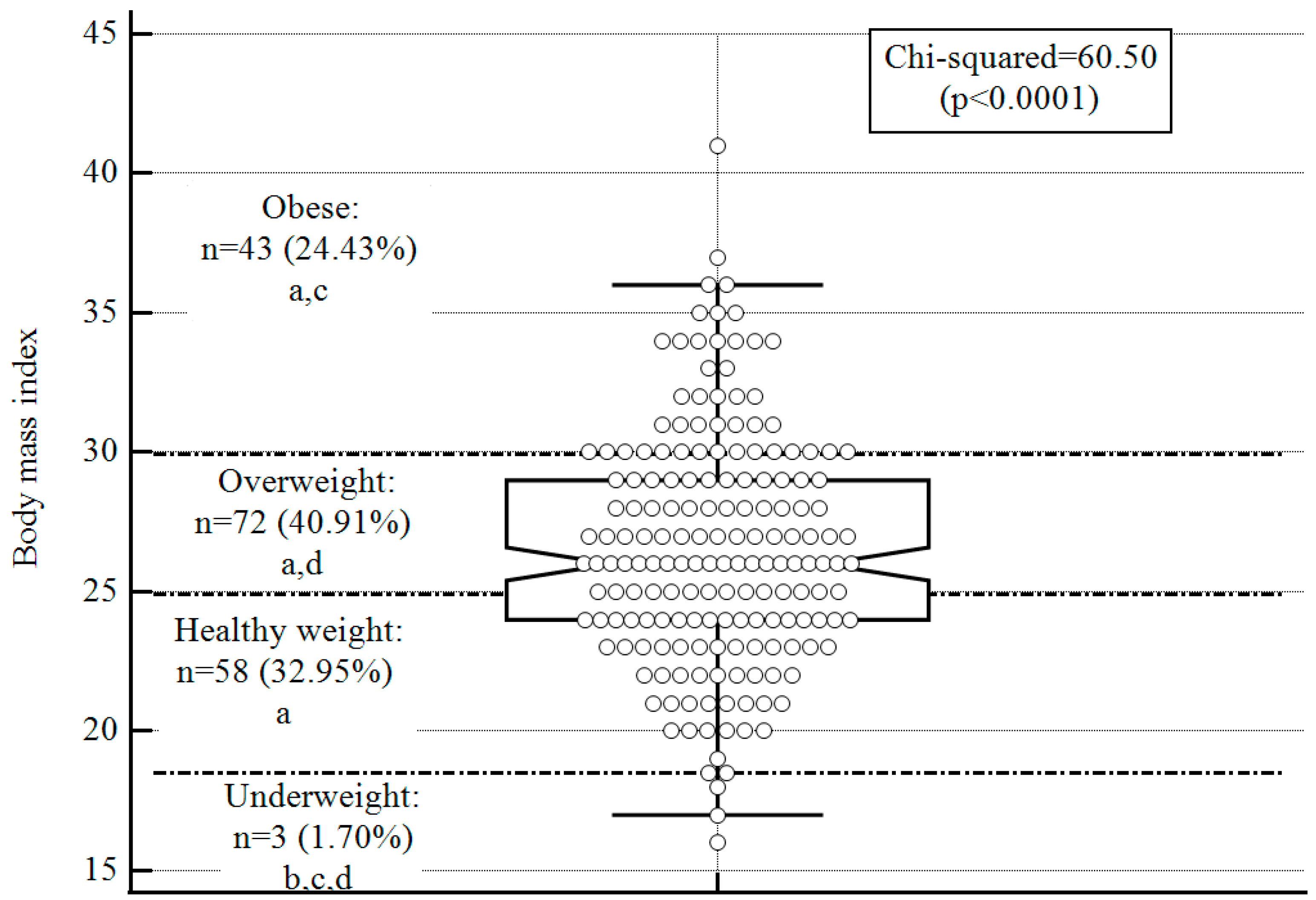

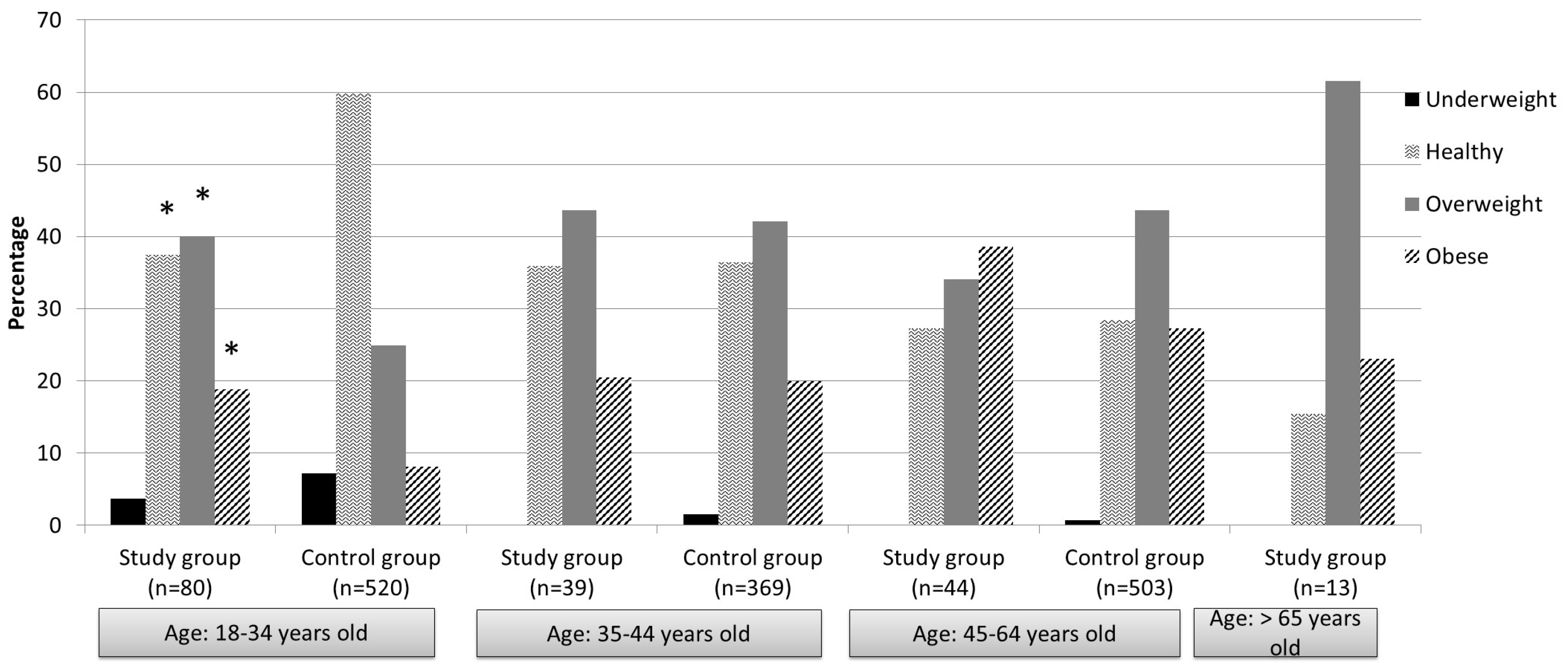

3.3. Weight Status

Differences in Weight Change based on Environmental, Emotional, Imprisonment, Socio-Demographic, and Weight Characteristics

3.4. Subjective Health Status (SHS)

Differences in based on Environmental, Emotional, Imprisonment, Socio-Demographic, and Weight Characteristics

3.5. Prediction of Weight Change in Prison and SHS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Travis, J.; Western, B.; Redburn, F.S. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nowotny, K.M.; Seide, K.; Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. Risk of COVID-19 infection among prison staff in the United States. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Best Practices Portal [Internet]. European Union. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/dyna/bp-portal/practice.cfm?id=103 (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Woodall, J.; Freeman, C. Developing health and wellbeing in prisons: An analysis of prison inspection reports in Scotland. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of National Security. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/reports/2019_ort/he/%D7%93%D7%95%D7%97%20%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%AA%D7%99%20%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%A1%D7%95%D7%9D%2001.07.20.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Zullo, R. An Input Adjustment Method for Challenging Privatization: A Case from Michigan Prison Health Services. Labor Stud. J. 2017, 42, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gueta, K. Childhood abuse and mental health problems: Does gender matter? Psychiatr. Q. 2016, 87, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.A.; Thompson, S.H. What are we feeding our inmates? J. Correct Health Care 2012, 18, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Nianogo, R.A.; Arah, O.A. Weight gain during incarceration: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, J.A.H. Changes in Weight Experienced by Female Inmates in the Federal Bureau of Prisons; Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2000; Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/49a9b292448c21167d2256d12fb24203/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Pagarolas-Soler, M.; Alonso-Gaitón, P.; Sapera-Miquel, N.; Valiente-Soler, J.; Sánchez-Roig, M.; Coll-Cámara, A. Diagnosed diabetes and optimal disease control of prisoners in Catalonia. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 2020, 22, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzke, A.J.; Baillargeon, J.G.; Pruitt, S.L.; Pulvino, J.S.; Paar, D.P.; Kelley, M.F. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among inmates in the Texas prison system. J. Urban Health 2010, 87, 486–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeni Njonnou, S.R.; Boombhi, J.; Etoa Etoga, M.C.; Tiodoung Timnou, A.; Jingi, A.M.; Nkem Efon, K.; Mbono Samba Eloumba, E.A.; Ntsama Essomba, M.J.; Kengni Kebiwo, O.; Tsitsol Meke, A.N.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes and associated risk factors among a group of prisoners in the Yaoundé central prison. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 5016327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voller, F.; Silvestri, C.; Martino, G.; Fanti, E.; Bazzerla, G.; Ferrari, F.; Grignani, M.; Libianchi, S.; Pagano, A.M.; Scarpa, F.; et al. Health conditions of inmates in Italy. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, S.F.; Adane, K. One-fourth of the prisoners are underweight in Northern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, L.; Stöver, H.; Jürgens, R.; Gatherer, A.; Nikogosian, H. (Eds.) Health in Prisons: A WHO Guide to the Essentials in Prison Health; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/99018/E90174.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- da Costa, F.A.; Verschuuren, M.; Andersen, Y.; Stürup-Toft, S.; Lopez-Acuña, D.; Ferreira-Borges, C. The WHO Prison Health Framework: A framework for assessment of prison health system performance. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Well-Being Concepts. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Argüello-González, A.J.; García-Zazueta, M.A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in a Mexican prison. Rev. Española De Sanid. Penit. 2020, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürup-Toft, S.; O’Moore, E.J.; Plugge, E.H. Looking behind the bars: Emerging health issues for people in prison. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 125, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandergrift, L.A.; Christopher, P.P. Do prisoners trust the healthcare system? Health Justice 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Brown, W.J.; Trost, S.G.; Bauman, A.; Mummery, K.; Owen, N. Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2004, 7, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; De Ridder, D.T.; De Vet, E.; De Wit, J.B. Minority talks: The influence of descriptive social norms on fruit intake. Psychol. Health 2012, 27, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Megeid, F.Y.; Abdelkarem, H.M.; El-Fetouh, A.M. Unhealthy nutritional habits in university students are a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 621–627. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Epel, O.; Kaplan, G. General subjective health status or age-related subjective health status: Does it make a difference? Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 53, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Saad, K.; Endevelt, R.; Goldsmith, R.; Shimony, T.; Nitsan, L.; Shahar, D.R.; Keinan-Boker, L.; Green, M.S.; Kalter-Leibovici, O. Adaptation and predictive utility of a Mediterranean diet screener score. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2928–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, K.; Plugge, E.; Foster, C.; Doll, H. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases in prison populations worldwide: A systematic review. Lancet 2012, 379, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shieh, C.; Cullen, D.L.; Pike, C.; Pressler, S.J. Intervention strategies for preventing excessive gestational weight gain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, K.; Armstrong, D.; Dregan, A. Systematic review into obesity and weight gain within male prisons. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 12, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 28 February 2023).

- Clarke, J.G.; Waring, M.E. Overweight, obesity, and weight change among incarcerated women. J. Correct Health Care 2012, 18, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bondolfi, C.; Taffe, P.; Augsburger, A.; Jaques, C.; Malebranche, M.; Clair, C.; Bodenmann, P. Impact of incarceration on cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review and meta-regression on weight and BMI change. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e039278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Williams, D.R.; Kawachi, I.; Okechukwu, C.A. Incarceration and adult weight gain in the National Survey of American Life (NSAL). Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.L.; Bradford, R.K. The impact of incarceration on obesity: Are prisoners with chronic diseases becoming overweight and obese during their confinement? J. Obes. 2015, 2015, 532468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Rioux, F.; Diasparra, M.; Richard, C.; Dubois, L. An exploration of reported food intake among inmates who gained body weight during incarceration in Canadian federal penitentiaries. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, K.; Armstrong, D.; Dregan, A. Prisons and Embodiment: Self-Management Strategies of an Incarcerated Population. J. Correct. Health Care 2019, 25, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augsburger, A.; Neri, C.; Bodenmann, P.; Gravier, B.; Jaquier, V.; Clair, C. Assessing incarcerated women’s physical and mental health status and needs in a Swiss prison: A cross-sectional study. Health Justice 2022, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravata, D.M.; Smith-Spangler, C.; Sundaram, V.; Gienger, A.L.; Lin, N.; Lewis, R.; Stave, C.D.; Olkin, I.; Sirard, J.R. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health. JAMA 2007, 298, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.E.; Adamson, S.; Korchinski, M.; Granger-Brown, A.; Ramsden, V.R.; Buxton, J.A.; Espinoza-Magana, N.; Pollock, S.L.; Smith, M.J.; Macaulay, A.C.; et al. Incarcerated women develop a nutrition and fitness program: Participatory research. Int. J. Prison Health 2013, 9, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A.; Milner, K.A.; Heng, C.; Greer, A.E.; DeNisco, S. Implementation and evaluation of a physical activity and dietary program in federal incarcerated females. J. Corr. Health Care 2018, 24, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Linsell, L.; Adeniji, T.; Sariaslan, A.; Fazel, S. Self-harm in prisons in England and Wales: An epidemiological study of prevalence, risk factors, clustering, and subsequent suicide. Lancet 2014, 383, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crewe, B.; Hulley, S.; Wright, S. Swimming with the tide: Adapting to long-term imprisonment. Justice Q. 2017, 34, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ginneken, E.F.J.C.; Palmen, H.; Bosma, A.Q.; Sentse, M. Bearing the weight of imprisonment: The relationship between prison climate and well-being. Crim. Justice Behav. 2019, 46, 1385–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean (SD) [Range] OR n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Age, years: mean (SD) [range] | 39.03 (13.99) [18.00–82.00] | |

| Gender: n (%) | Male | 176 (100.00) | |

| Country of origin: n (%) | Native to the country | 133 (75.56) | |

| Foreign | 43 (24.43) | ||

| Marital status: n (%) | Single | 56 (31.82) | |

| In partnership | 14 (7.95) | ||

| Married | 61 (34.66) | ||

| Separated | 9 (5.11) | ||

| Divorced | 28 (15.91) | ||

| Widowed | 8 (4.55) | ||

| School, years: mean (SD) [range] | 9.88 (3.24) [0.00–15.00] | ||

| Educational level: n (%) | Never went to school | 11 (6.25) | |

| Only primary school | 36 (20.45) | ||

| Graduated from school without a diploma | 33 (18.75) | ||

| Basic diploma | 41 (23.30) | ||

| Professional diploma | 23 (13.07) | ||

| College diploma | 7 (3.98) | ||

| Technical or professional certification | 9 (5.11) | ||

| Professional degree/course | 16 (9.09) | ||

| Imprisonment characteristics | Years of detention: n (%) | Up to one year: n (%) | 24 (13.64) |

| One to five years: n (%) | 63 (35.80) | ||

| At least five years: n (%) | 89 (50.57) | ||

| Family visits in the previous month: n (%) | Never | 41 (23.30) | |

| Once | 57 (32.39) | ||

| Two to four | 55 (31.25) | ||

| More than four | 23 (13.07) | ||

| Independent Variables | Weight Change | Between Group Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gained Weight: Mean (SD) OR n (%) | Lost Weight: Mean (SD) OR n (%) | No Weight Change: Mean (SD)_ OR n (%) | F-Ratio (p-Value) OR Chi-Square (p-Value) | |||

| Total: n (%) | 102 (57.95) | 43 (24.43) | 31 (17.61) | 50.90 (0.001) | ||

| Environmental factors | Physical activity level, minutes: mean (SD) | 115.49 (242.20) | 74.79 (103.75) | 115.48 (203.20) | 1.06 (0.70) | |

| Eating behavior, score: mean (SD) | 4.76 (2.43) | 4.61 (2.38) | 4.57 (2.79) | 0.06 (0.94) | ||

| Products bought in the prison store | Fruits/vegetables, yes: n (%) | 8 (7.84) | 5 (11.63) | 3 (9.68) | 0.60 (0.73) | |

| Legumes/grains, yes: n (%) | 47 (46.07) | 19 (44.19) | 11 (35.45) | 1.08 (0.58) | ||

| Sweets, yes: n (%) | 32 (31.37) | 12 (27.91) | 11 (35.45) | 0.42 (0.80) | ||

| Animal products, yes: n (%) | 62 (60.78) | 26 (60.46) | 21 (67.74) | 0.50 (0.77) | ||

| Oils/nuts, yes: n (%) | 24 (23.53) | 4 (9.30) | 5 (16.13) | 4.18 (0.12) | ||

| Emotional status, score: mean (SD) | 20.74 (4.78) | 20.92 (4.74) | 21.06 (4.26) | 0.06 (0.94) | ||

| Imprisonment factors | Prison time | Up to one year: n (%) | 6 (5.88) b,c | 13 (30.23) a,c | 5 (16.12) a,b | 16.35 (0.002) |

| One to five years: n (%) | 38 (37.25) | 12 (27.90) c | 13 (41.94) b | 12.35 (0.003) | ||

| At least five years: n (%) | 58 (58.86) b,c | 18 (41.86) a | 13 (41.94) a | 16.46 (0.002) | ||

| Family visits | No: n (%) | 26 (25.49) | 6 (13.95) | 9 (29.03) | 2.96 (0.22) | |

| Sociodemographic factors | Age, years: mean (SD) | 39.13 (13.96) | 39.08 (15.60) | 38.60 (12.01) | 0.01 (0.98) | |

| Native to the country, yes: n (%) | 79 (77.45) | 32 (74.42) | 22 (70.97) | 0.58 (0.74) | ||

| Marital status, in a relationship: n (%) | 37 (36.27) | 24 (55.81) | 14 (45.16) | 4.82 (0.08) | ||

| Education, school years: mean (SD) | 9.67 (3.50) | 10.51 (2.13) | 9.76 (3.53) | 3.56 (0.03) | ||

| Weight status | Current BMI: mean (SD) | 27.63 (4.32) b | 24.53 (3.54) a | 25.64 (4.00) | 9.55 (<0.001) | |

| Current BMI status, healthy weight: n (%) | 25 (24.51) b,c | 20 (46.51) a,c | 13 (12.75)a,b | 5.63 (0.01) | ||

| BMI at 18: mean (SD) | 20.23 (7.54) | 17.44 (10.65) | 17.74 (9.35) | 2.01 (0.13) | ||

| Independent Variables | SHS | Between-Group Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good, Very Good, Excellent (n = 129): Mean (SD) OR n (%) | Bad and Very Bad (n = 47): Mean (SD) OR n (%) | Statistic t (p-Value) OR Chi-Square (p-Value) | ||||

| Environmental factors | PA level, minutes: mean (SD) | 129.81 (290.25) | 121.25 (330.21) | −0.16 (0.86) | ||

| Eating behavior, score: mean (SD) | 4.82 (2.41) | 4.31 (2.49) | −0.96 (0.33) | |||

| Products bought in the prison store | Fruits/vegetables, yes: n (%) | 13 (10.07) | 3 (6.38) | 0.56 (0.45) | ||

| Legumes/grains, yes: n (%) | 54 (41.86) | 23 (48.94) | 0.69 (0.40) | |||

| Sweets, yes: n (%) | 42 (32.56) | 13 (27.66) | 0.38 (0.53) | |||

| Animal products, yes: n (%) | 80 (62.02) | 29 (61.70) | 0.01 (0.96) | |||

| Oils/nuts, yes: n (%) | 25 (19.38) | 8 (17.02) | 0.12 (0.72) | |||

| Emotional status, score: mean (SD) | 21.52 (4.46) | 18.88 (4.70) | −3.29 (0.001) | |||

| Imprisonment factors | Prison time | Up to one year: n (%) | 19 (14.73) | 5 (10.64) | 0.48 (0.48) | |

| One to five years: n (%) | 52 (40.31) | 11 (23.40) | 5.96 (0.01) | |||

| At least five years: n (%) | 58 (44.96) | 31 (65.95) | 6.01 (0.01) | |||

| Family visits | No: n (%) | 102 (79.07) | 33 (70.21) | 1.50 (0.22) | ||

| Sociodemographic factors | Age, years: mean (SD) | 37.41 (13.02) | 43.46 (15.66) | 2.58 (0.01) | ||

| Native to the country, yes: n (%) | 97 (75.19) | 36 (76.60) | 0.03 (0.84) | |||

| Marital status, in a relationship: n (%) | 57 (44.19) | 18 (38.30) | 0.48 (0.48) | |||

| Education: school years: mean (SD) | 9.68 (3.25) | 10.45 (3.19) | 1.28 (0.20) | |||

| Weight status | Current BMI: mean (SD) | 22.39 (1.60) | 15.28 (<0.0001) | 15.28 (<0.001) | ||

| Current BMI status, healthy weight: n (%) | 45 (34.89) | 13 (27.66) | 0.36 (0.06) | |||

| BMI at 18: mean (SD) | 16.08 (9.15) | 20.60 (8.21) | 3.18 (0.001) | |||

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Coefficient | Standard Error | Odds Ratio | Wald | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight change (reference—gained weight) | Constant | −4.17 | 1.76 | - | 5.56 | - | 0.01 | |

| Time in prison (reference value—at least five years) | Up to one year | −1.69 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 9.63 | 0.06–0.53 | 0.001 | |

| One to five years | −0.19 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.29 | 0.40–1.66 | 0.58 | ||

| Current BMI | 0.17 | 0.06 | 1.19 | 8.10 | 1.05–1.35 | 0.004 | ||

| BMI category | Healthy | 0.22 | 0.49 | 1.25 | 0.20 | 0.47–3.32 | 0.64 | |

| Model summary | Chi-Square = 28.55, p < 0.0001, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.22 | |||||||

| SHS: reference: bad and very bad) | Constant | −0.67 | 1.60 | - | 0.17 | - | 0.67 | |

| Emotional status score | 0.16 | 0.04 | 1.17 | 12.78 | 1.07–1.28 | 0.0003 | ||

| Time in prison | Up to one year | 0.32 | 0.59 | 1.38 | 0.30 | 0.43–4.44 | 0.58 | |

| One to five years | 0.83 | 0.45 | 2.31 | 3.44 | 0.95–5.61 | 0.06 | ||

| Age, years | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 8.50 | 0.93–0.98 | 0.0003 | ||

| Current BMI | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.04 | 0.92–1.11 | 0.82 | ||

| BMI at 18 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.17 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.40 | ||

| Model summary | Chi-square = 26.25, p = 0.0002, Nagelkerke R2 =0.22 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aharon, S.B.; Regev, O.; Tesler, R.; Barak, S.; Shapira, Y.; Weiss, Y.; Shtainmetz, N.; Vaknin, Y.; Goldstein, L.; Ben-Zvi, K.; et al. Assessment of Nutritional Status and Health Perception among Male Inmates in Israeli Prisons. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2255. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102255

Aharon SB, Regev O, Tesler R, Barak S, Shapira Y, Weiss Y, Shtainmetz N, Vaknin Y, Goldstein L, Ben-Zvi K, et al. Assessment of Nutritional Status and Health Perception among Male Inmates in Israeli Prisons. Nutrients. 2023; 15(10):2255. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102255

Chicago/Turabian StyleAharon, Shani Ben, Ofer Regev, Riki Tesler, Sharon Barak, Yair Shapira, Yossi Weiss, Noa Shtainmetz, Yochanan Vaknin, Liav Goldstein, Kathrine Ben-Zvi, and et al. 2023. "Assessment of Nutritional Status and Health Perception among Male Inmates in Israeli Prisons" Nutrients 15, no. 10: 2255. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102255

APA StyleAharon, S. B., Regev, O., Tesler, R., Barak, S., Shapira, Y., Weiss, Y., Shtainmetz, N., Vaknin, Y., Goldstein, L., Ben-Zvi, K., & Birk, R. (2023). Assessment of Nutritional Status and Health Perception among Male Inmates in Israeli Prisons. Nutrients, 15(10), 2255. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102255