Parental Perceptions on the Importance of Nutrients for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Sample

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Description

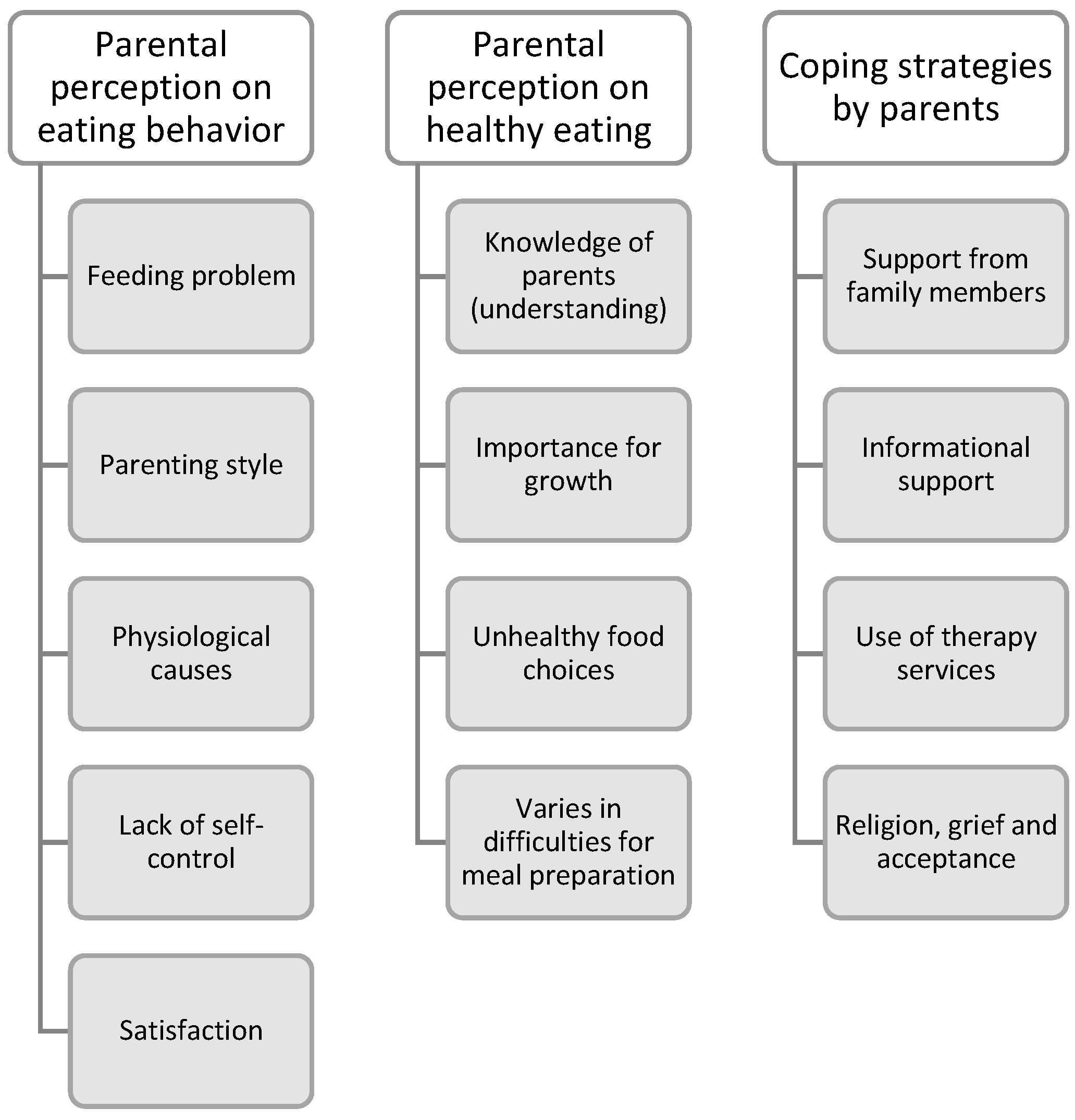

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Parental Perception of Eating Behavior

“Oh okay…my child, he seems like a picky eater. He doesn’t like soft mushy texture foods. He likes crunchy food. He refuses soft texture. [The mom describes his son’s eating behavior] And his eating behavior is seasonal. He used to take rice previously. But once he feels bored over it, he will refuse to eat. He will then choose others food like bread. Then the cycle repeats, when he feels bored over certain types of food; then, he will choose other types of food again.” (P8)

“Don’t mention fruits. He refuses cause of the texture of the fruit. He is only keen to try it by biting once or licking with his tongue, then that’s it. Even like vegetables, I have become crispy texture; only, then is he willing to eat.” (P8)

“…my child always with spaghetti. He always eats spaghetti. Sometimes will eat rice; but only with his favorite dish. He likes fries, fried prawn crackers. My child refuses new food.” (P11)

“I notice that my child is somehow like a picky eater; because he chooses his food. When we offer him others, he rejects the food. My child will eat that same type of food daily, keep repeating, and won’t feel bored.” (P12)

“My child is picky with his food. He doesn’t like something too salty or too soft in texture. He only likes to eat cocoa-based cereals. Or he only takes “nasi lemak”, that’s all. He doesn’t like fruits and vegetables. Even if we hide the vegetables by blending them, he seems to know, then he refuses to eat.” (P13)

“Yes! [The parent agrees with the son eating behavior] He is rigid with his routine; and his food choices. If he insists on that food, [hah—parent expression], that’s the only food he chooses. For example, for breakfast, he only wants fried vermicelli. Then followed by white rice and fried chicken, then white rice with egg…and it must be scrambled egg. These are the only food groups he takes. Yea [Agree from a parent], his eating behavior is so rigid.” (P10)

“Yes, sometimes, he will only focus on eating during his eating time. Do not disturb him. And then, if, let’s say, he already chose a destined place to eat, he will not change to another place anymore; that is the only place he likes. He will wait for his siblings to finish using that place or chair. And then even the plate, he also got his specific plate colors to use, like pink or dark purple. He will only go for that specific place and plate.” (P9)

“Yup, I need to feed my child. But for foods like fish crackers or fries, he still can eat by himself. But he can’t hold properly; he is not strong yet.”

“…previously my child refused to eat. This is based on my opinion. I’m not too sure about the other parents. But in my opinion, I will act in this way. I will not follow their demand. Some parents sympathize with their children and follow their demands, but not me. When my child refuses to accept new foods, I will explain to them. You need it to keep telling, and they will know the food is tasty after they try it.” (P5)

“We must guide him; we cannot just leave him like that. They should eat the same as us. But when I sent him to an early intervention program, I noticed that most of them liked to eat chicken. So, I did was, I told the principal in charge to give him the foods that they serve. If he doesn’t want to eat, then you just monitor him. I didn’t pack him any food; I just packed him mineral water. The results are okay; he can accept little by little.” (P9)

“…I know my child doesn’t like fruits and vegetables. But, no matter how he needs to take fruits and vegetables. So, I will dip them with flour and egg for vegetables to make them crispy and fry them. Thank God, he eats it.” (P8)

“…For now, for your information, I process food like nuggets and sausages for him from scratch. Because he likes to eat fast food, it will not be a wise choice if we keep providing him with it. So, I will process the food myself and add in vegetables inside.” (P12)

“Eating is essential…no matter where we go, we need to eat. But for my child, because he is a special child, so even though we do not have much money, as a parent, we still need to prioritize him [for buying food]. He is not like us, we can be flexible, but he can’t. So, we have to fulfill the foods that he wants.” (P12)

“For now, I’m feeding all of my children. I refuse to let them eat by themselves as they will not finish the food and mess up the places. Hence, every time, I will feed them, all of them.” (P4)

“…he can eat himself, but I won’t allow it. This includes my eldest son (a typical development child); I will also feed him. For example, I’m serving them fish, but I’m afraid they aren’t aware of the fish bones. And one more thing, they will be picky if they eat by themselves. So, if I’m the one that feeds them, everything that I feed, they will eat it.” (P4)

“He…during his mealtime, he is unable to sit quietly. So, I must let him watch something [gadget/TV] for a while. Yup, watch television or let him watch the video through his handphone to focus during mealtime. And I still feed him because he is not good at self-feeding.” (P2)

“We feel very challenged when feeding my child because his upper limbs will keep moving uncontrollably. We only can feed him when he knows how to open his mouth, and we need to trigger him to open his mouth. He seems like he doesn’t have any hunger feeling.” (P11)

“My child...he can’t sit, and he doesn’t want to eat. He even refuses to look into the food…he has minimal interest in the food.” (P14)

“I don’t know how, but my child will keep repeating, asking for food. He is still non-verbal. But that doesn’t stop him from requesting food. [laughing] He will bring you to the kitchen because he wants to eat. To ease our convenience, we will prepare light snacks like fries. For example, at noon, I gave him fries, he would finish them (one bowl of it), then he would play himself. But after that, he will ask for food again…is like every 30mins he will ask again…” (P12)

“For her…if the food that she likes…she will eat a lot until I need to hide it. I usually won’t give her too much because I know she doesn’t know how to stop. [Laugh] I think she doesn’t know the feeling of fullness. Like us, when we know we are full, we will stop eating. But for her, for example, yesterday, I provided her with fried noodles [I control the portion]. But after half an hour, she requested cream crackers and ate around ten pieces. I even purposely stop buying it because she will eat a lot and be unable to control it.” (P14)

“If is my child, I don’t think there is a problem with his eating behavior. He is okay so far. He can eat all. If he wants to talk about his eating behavior, I would only say it is hard to sit while eating. But he will eat all; he will finish all the food.” (P1)

“He is not choosy on his foods. He likes to eat. Everything you give it to him (rice, fruits, spicy, sweet, sour, etc.), he will finish all.” (P1)

“Okay…got some autistic children. They are like a picky eater. But I don’t think this happens to my child. It is easy to handle my child during mealtime. She eats every food group–chicken, fish, and vegetables, she eats. For instance, some autistic children are sensitive to the aroma, but this is not happening to my child. So, to me, it is not the same. My child can eat all.” (P2)

3.2.2. Parental Perception of Healthy Eating

“From my understanding, healthy eating to me is about vegetables, fruits, and rice. That’s all on what I understand, as simple as this [laughing], and, must be able to feel full. Junk food is not healthy eating.” (P1)

“Healthy eating is like must have fish, chicken, vegetables. Have to be balanced, the foods need to be balanced. Yes, balance diet. It is not about sweet food.” (P2)

“Okay, healthy eating is like balanced eating, that is what I can understand. Have to make sure his nutrition is enough, needs to have protein, carbohydrate, and no sugary things.” (P3)

“I hope that I can help him with food varieties since he is a picky eater; I am worried if his diet lacks fiber or any other nutrients. If possible, I hope he can have varieties of food in terms of the sources.” (P8)

“Supposing consists of protein, consists of basic meals. But because he dislikes certain food, sometimes I will provide him with multivitamins. And now you look at his weight increasing, so I think better I should stop the vitamin [laughing].” (P9)

“Okay, healthy eating is like referring back to our food pyramid. Means, we have to provide the quantity that the food pyramid had suggested, including the vegetables, fish, and rice.” (P12)

“Healthy eating is important for his growth.” (P2)

“Healthy eating is very important, important for his growth. Even though he is a special child, he still needs to grow like usual kids. Am I correct? Autism affects his behavior, but he is growing still the same.” (P3)

“They have to eat healthily. It is essential as it will affect their development in general and also their brain function.” (P4)

“…we know about our child; he, is not suitable with too much intake of sugary food, he will become hyperactive and starts giggling by himself and also running around. Then we ended up feeling tired as parent, so we have to control his intake of sugar.” (P3)

“Healthy eating is important, especially for his growth. If able to eat healthily, I think it can help him behave well. It will affect his emotion, especially towards sweetened food or beverages, because it affects his sleep cycle, from my observation.” (P8)

“Okay, I only buy free-range chicken; the same goes for the egg. I am worried and anxious about the quality of the food. And if it is vegetables, usually I’ll buy red spinach. Nowadays, I get so much news about animal injection or polluted plantations that I won’t buy it. Their health is my main priority now.”

“I think I’m quite okay with it because my child is not a picky eater, so it is quite easy for me to prepare the food. It is not the same as mentioned, where I have to prepare differently for him. To me, it is easy, is easy for me to cook for everyone to eat.” (P1)

“I feel it is easy for me to prepare healthy food for my child. I didn’t help him much; I’ll just prepare fruits and vegetables for him [extra]. So, when he is hungry, he will take himself. I feel there are not many issues for him.” (P3)

“Challenges arise when the food (food availability) that we prepare, my child refuses. So, we have to find him the alternatives that my child will accept (with our affordability).” (P12)

“It is difficult. Firstly, the portion size of the food is already more than the recommended; second, the unhealthy food choices that my child likes. She likes sweetened food. For example, she already had her breakfast, but I noticed she would go and make herself a cup of hot cocoa-sweetened drink after a while. She knows where I usually hide it.” (P14)

“I feel there is difficulty to help my child with healthy eating—sometimes we do not have much encouragement to control his portion intake because he will misbehave (scream) if we do not go according to his request.” (P15)

3.2.3. Coping Strategies

“Oh, to be honest, it is quite hard to answer, but it is okay; I can…[laughing] I do not deny; it is stressful. Furthermore, with the current situation [movement control order], we can’t go out quite often. But I feel grateful because my child does not show tantrums. He is not like other autistic children; [strongly affirming] he is not. And, I feel less stressed because he got his elder sister that will help me keep an eye on him, and I am so lucky to have my parents [children’s grandparents] that stay near me; so that I can bring him to their house. My husband helps me a lot too. When he is not working, he will take care of him. We did set up a rule where we will take turns to clean up our son if he passes motion [laughing].” (P1)

“…and one more thing, my mom supports me the most. She keeps encouraging me; she is my pillar of support. Sometimes she will stay over at my house and help me take care of my child. So, when you know someone is supporting you, eventually, you won’t feel stressed. I am grateful for everything.” (P3)

“...and supports from family members. Even though my husband is very busy, he always is my listener and gives opinions.” (P8)

“...social media…I joined the autism social media group page; and learned a lot about my child’s character, how to handle my child, and the suitable toys for an autistic child because they are not like the typical child. When you buy them toys, they will give you an excited reaction. Autism children will not give you this kind of response. So, for my child, I plan to train him to play with puzzles to help with his focus and eye contact. I did a lot of readings from the autism club social media page and also my own research.” (P3)

“Of course, it is stressful, but I will do lots of reading related to my autistic child; and how I can handle them well. Besides reading, I will also join online classes related to autism; it is like doing your research to apply it to my child. The stress is not daily, maybe once in 2 to 3 weeks. The stress is not affecting my daily routine.” (P8)

“To me, so far, my child is okay. When he was small (a baby), he was easy to take care of. But when he was around 5 to 6 years old, he started to develop tantrums and face sleep disturbance. So, we went for paid therapy services to learn about handling his sleep disturbance, like brushing, and covering him up to calm him. We are able to see the effects on him; he is getting better.” (P2)

“It is to this extent…when he eats curry puff, he only eats the crust and removes the inner ingredients of it. Hence, I need to send him to paid therapy services just to train him on eating curry puff.” (P14)

“Previously, I do feel stressed…the moment when I know my child is autistic. I couldn’t accept it at that moment; even my husband also can’t accept it. Because the way my child acts to us is like he is a normal child. But, after a few months, I am getting better with it; I can accept it. I keep doing self-talk [laughing]. I can slowly accept it. And I always told myself that some people even a tougher life than us. We are way better than them, and I think this is what God wants us to experience, so yeah, we accept that our child is an autistic child.” (P9)

“…In my first and second years of knowing my child is autistic, I cry badly. Especially when others criticize your child, I can’t handle it. But right now, I’m getting better. I will slowly understand my child and find out the solution for it. So, the tension will be lesser, and you will be able to handle it better.” (P12)

“When she was small, the stress level was high. Because she is still small and unable to understand our instructions. The most challenging part was she didn’t want to sit down quietly. We couldn’t go anywhere, and my social life had changed. But, as she grows up, we can slowly adapt it in our life, so we are getting better now. And right now, she’s able to eat by herself; she can follow instructions. So, whenever I feel tension, I will say this to myself—even though she is autistic, we have to feel gratitude that our child can be independent in her basic life. And one more thing, pray to God. Don’t compare your own with others. We won’t know the hardship of others.” (P14)

4. Discussion

4.1. Parental Perception of Eating Behavior

4.2. Parental Perceptions of Healthy Eating

4.3. Parental Coping Strategies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC. What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)? Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html (accessed on 15 February 2022).

- Autism Speaks. Autism and Health: A Special Report by Autism Speaks. Autism Speaks. 2012. Available online: https://www.autismspeaks.org/science-news/autism-and-health-special-report-autism-speaks (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- CDC. Treatment and Intervention Services for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/treatment.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Baio, J.; Washington, A.; Patrick, M.; DiRienzo, M.; Christensen, D.L.; Wiggins, L.D.; Pettygrove, S.; Andrews, J.G.; et al. Prevalence and autism spectrum disorder among children age 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. CPG Management of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Putrajaya: Malaysian Health Technology Assessment Section (MaHTAS). 2014. Available online: http//www.moh.gov.myhttp//www.acadmed.org.myhttp//www.psychiatry-malaysia.org (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Margari, L.; Marzulli, L.; Gabellone, A.; de Giambattista, C. Eating and mealtime behaviors in patients with autism spectrum disorder: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 2083–2102. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32982247/ (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, K.L.; Anderson, S.E.; Curtin, C.; Must, A.; Bandini, L.G. A comparison of food refusal related to characteristics of food in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1981–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, C.P.; Pondé, M.P. Narratives of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders: Focus on eating behavior. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017, 39, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, R.F.; Cutler, A. Dysregulated breastfeeding behaviors in children later diagnosed with autism. J. Perinat Educ. 2015, 24, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Gray, H.; Sinha, S.; Buro, A.W.; Robinson, C.; Berkman, K.; Agazzi, H.; Shaffer-Hudkins, E. Early history, mealtime environment, and parental views on mealtime and eating behaviors among children with ASD in Florida. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1867. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30513809/ (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Huxham, L.; Marais, M.; van Niekerk, E. Idiosyncratic food preferences of children with autism spectrum disorder in England. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 34, 90–96. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16070658.2019.1697039 (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Emond, A.; Emmett, P.; Steer, C.; Golding, J. Feeding symptoms, dietary patterns, and growth in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e337–e342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel-Lachiusa, J.; Andrianopoulos, M.V.; Mailloux, Z.; Cermak, S.A. Sensory differences and mealtime behavior in children with autism. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 1–8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26379266/ (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Berding, K.; Donovan, S.M. Diet can impact microbiota composition in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geier, D.A.; Kern, J.K.; Geier, M.R. A prospective cross-sectional cohort assessment of health, physical, and behavioral problems in autism spectrum disorders. Mædica 2012, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thullen, M.; Bonsall, A. Co-parenting quality, parenting stress, and feeding challenges in families with a child diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 878–886. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28070782/ (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayes, S.D.; Zickgraf, H. Atypical eating behaviors in children and adolescents with autism, ADHD, other disorders, and typical development. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 2019, 64, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twachtman-Reilly, J.; Amaral, S.C.; Zebrowski, P.P. Addressing feeding disorders in children on the autism spectrum in school-based settings: Physiological and behavioral issues. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2008, 39, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.; Dalrymple, N.; Neal, J. Eating habits of children with autism. Pediatr. Nurs. 2000, 26, 259–264. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12026389/ (accessed on 16 February 2022).

- Whiteley, P.; Rodgers, J.; Shattock, P. Feeding patterns in autism. Autism 2000, 4, 207–211. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1362361300004002008 (accessed on 4 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L.G.; Magill-Evans, J.; Rempel, G.R. Mothers’ Challenges in Feeding their Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder-Managing More Than Just Picky Eating. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2012, 24, 19–33. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10882-011-9252-2 (accessed on 4 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bandini, L.G.; Anderson, S.E.; Curtin, C.; Cermak, S.; Evans, E.W.; Scampini, R.; Maslin, M.; Must, A. Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. J. Pediatr. 2010, 157, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.H.; Hart, L.C.; Manning-Courtney, P.; Murray, D.S.; Bing, N.M.; Summer, S. Food Variety as a Predictor of Nutritional Status Among Children with Autism. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 549. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC8108121/ (accessed on 4 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Schreck, K.A.; Williams, K. Food preferences and factors influencing food selectivity for children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2006, 27, 353–363. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16043324/ (accessed on 4 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.W.; Must, A.; Anderson, S.E.; Curtin, C.; Scampini, R.; Maslin, M.; Bandini, L. Dietary patterns and body mass index in children with autism and typically developing children. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.A.S.; Ramli, N.S.; Hamzaid, N.H.; Hassan, N.I. Exploring Eating and Nutritional Challenges for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parents’ and Special Educators’ Perceptions. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2530. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/9/2530/htm (accessed on 23 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Nor, N.K.; Ghozali, A.H.; Ismail, J. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and associated risk factors. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Estes, A.; Swain, D.M.; MacDuffie, K.E. The effects of early autism intervention on parents and family adaptive functioning. Pediatr. Med. 2019, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.; Rogers, S.; Munson, J.; Smith, M.; Winter, J.; Greenson, J.; Donaldson, A.; Varley, J. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e17–e23. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19948568/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, A.; Munson, J.; Rogers, S.J.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; Dawson, G. Long-Term Outcomes of Early Intervention in 6-Year-Old Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2015, 54, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Groen, A.D.; Wynn, J.W.; Smith, T. Randomized trial of intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 2000, 105, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, J.S.; van Hecke, A.V. Parent and Family Impact of Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Review and Proposed Model for Intervention Evaluation. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 15, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koegel, R.L.; Bimbela, A.; Schreibman, L. Collateral effects of parent training on family interactions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1996, 26, 347–359. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8792265/ (accessed on 4 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, M.; Ono, M.; Timmer, S.; Goodlin-Jones, B. The effectiveness of parent-child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2008, 38, 1767–1776. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18401693/ (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Symon, J.B. Parent Education for Autism: Issues in Providing Services at a Distance. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2016, 3, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.A.; Werner, S.E. Collateral effects of behavioral parent training on families of children with developmental disabilities and behavior disorders. Behav. Interv. 2002, 17, 75–83. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bin.111 (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Baker-Ericzén, M.J.; Brookman-Frazee, L.; Stahmer, A. Stress Levels and Adaptability in Parents of Toddlers with and without Autism Spectrum Disorders. Res. Pr. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2016, 30, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergüner-Tekinalp, B.; Akkök, F. The effects of a coping skills training program on the coping skills, hopelessness, and stress levels of mothers of children with autism. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2004, 26, 257–269. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:ADCO.0000035529.92256.0d (accessed on 5 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.P.; Kovshoff, H.; Brown, T.; Ward, N.J.; Espinosa, F.D.; Remington, B. Coping strategies in mothers and fathers of preschool and school-age children with autism. Autism 2005, 9, 377–391. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16155055/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.J. Harrdiness and social support as predictors of stress in mothers of typical children, children with autism, and children with mental retardation. Autism 2002, 6, 115–130. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11918107/ (accessed on 5 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.M.; Leon, S.C.; Phelps, C.E.R.; Dunleavy, A.M. The impact of child symptom severity on stress among parents of children with ASD: The moderating role of coping styles. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernhet, C.; Dellapiazza, F.; Blanc, N.; Cousson-Gélie, F.; Miot, S.; Roeyers, H.; Baghdadli, A. Coping strategies of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 747–758. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29915911/ (accessed on 24 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.R. Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2010, 4, 217–228. Available online: /record/2011-03277-008 (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Twoy, R.; Connolly, P.M.; Novak, J.M. Coping strategies used by parents of children with autism. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pr. 2007, 19, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang Bao, X. The Relationship of Parenting Styles and Obesity with Special Needs Children; University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2018; Available online: https://dc.uwm.edu/uwsurca/2018/Posters/114/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984; 725p, Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Stress_Appraisal_and_Coping.html?hl=es&id=i-ySQQuUpr8C (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Shohaimi, D.A.S.; Zulkifly, S.F.I.; Hasibuan, M.A.; Ismail, N.T.; Shareela, N.A.; Hamzaid, N.H.; Hassan, N.I. Knowledge of special nutrition for children with autism spectrum disorder among parents and special educators in Malaysia. J. Sains Kesihat. Malays. 2021, 19, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, X.Y.; Abd Rahim, A.A.; Abdul Talib, D.; Hamzaid, N.H.; Abdul Manaf, Z. A qualitative study on feeding practices among caregivers of Malay children and adolescents with autism. J. Sains Kesihat. Malays. 2019, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, F.; Zulkifli, A.; Rahman, P.A. Relationships between Sensory Processing Disorders with Feeding Behavior Problems Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2021, 17, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.Q.; Teo, C.M.; Tan, M.L.; Aw, M.M.; Chan, Y.H.; Chong, S.C. Feeding difficulties in Asian children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Neonatol. 2022, 63, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, L.G.; Curtin, C.; Eliasziw, M.; Phillips, S.; Jay, L.; Maslin, M.; Must, A. Food selectivity in a diverse sample of young children with and without intellectual disabilities. Appetite 2019, 133, 433–440. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30468805/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, H.; Blissett, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption in children and their mothers. Moderating effects of child sensory sensitivity. Appetite 2009, 52, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, B.Y.L. Motor difficulties in autism, explained. Spectrum 2020, 2–5. Available online: https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/motor-difficulties-in-autism-explained/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Lloyd, M.; MacDonald, M.; Lord, C. Motor skills of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2011, 17, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.N.; Landa, R.J.; Galloway, J.C. Current perspectives on motor functioning in infants, children, and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 1116–1129. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21546566/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lee Gray, H.; Chiang, H.M. Brief report: Mealtime behaviors of chinese American children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism. Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 892–897. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28070790/ (accessed on 16 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Benjasuwantep, B.; Chaithirayanon, S.; Eiamudomkan, M. Feeding problems in healthy young children: Prevalence, related factors and feeding practices. Pediatr. Rep. 2013, 5, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Feeding Guide. Pressure to Eat. Child Feeding Guide Loughborough University. 2017. Available online: https://www.childfeedingguide.co.uk/tips/common-feeding-pitfalls/pressure-eat/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Raising Children Network. Overeating: Autistic Children & Teens. Raising Children Network. 2020. Available online: https://raisingchildren.net.au/autism/health-wellbeing/eating-concerns/overeating-autistic-children-teenagers (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Di Martino, A.; Ross, K.; Uddin, L.Q.; Sklar, A.B.; Castellanos, F.X.; Milham, M.P. Functional brain correlates of social and nonsocial processes in autism spectrum disorders: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 65, 63–74. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18996505/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.; Uddin, L.Q. Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct. 2010, 214, 655–667. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/44639548_Saliency_switching_attention_and_control_A_network_model_of_insula_function (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2003, 13, 500–505. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12965300/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2007, 35, 22. Available online: https://pmc/articles/PMC2531152/ (accessed on 29 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors influencing children’s eating behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, T.; Rittenberry, L.; Cosart, C.; Owens, E.; Hebert, D.; de Moor, C. Socioenvironmental influences on children’s fruit, juice and vegetable consumption as reported by parents: Reliability and validity of measures. Public Health Nutr. 2000, 3, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S.; Lutz, S. Household, Parent, and Child Contributions to Childhood Obesity*. Fam. Relat. 2000, 573, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.O.; Power, T.G.; Orlet, J.; Mueller, S.; Nicklas, T.A. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite 2005, 44, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podlesak, A.K.M.; Mozer, M.E.; Smith-Simpson, S.; Lee, S.Y.; Donovan, S.M. Associations between parenting style and parent and toddler mealtime behaviors. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, 1006003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraguas, D.; Díaz-Caneja, C.M.; Pina-Camacho, L.; Moreno, C.; Durán-Cutilla, M.; Ayora, M.; González-Vioque, E.; de Matteis, M.; Hendren, R.L.; Arango, C.; et al. Dietary Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20183218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone, E.; Charman, T.; McConachie, H.; Warreyn, P. Prevalence and correlates of use of complementary and alternative medicine in children with autism spectrum disorder in Europe. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015, 174, 1277–1285. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25855095/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marí-Bauset, S.; Zazpe, I.; Mari-Sanchis, A.; Llopis-González, A.; Morales-Suárez-Varela, M. Evidence of the gluten-free and casein-free diet in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. J. Child Neurol. 2014, 29, 1718–1727. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24789114/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.S. The role of nutraceuticals in the management of autism. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 233–243. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC3804964/ (accessed on 17 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Malaysian Dietary Guidelines (MDG) 2020. Selangor: National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition. 2020; 290 p. Available online: https://nutrition.moh.gov.my/MDG2020/mobile/index.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Karen, A.; Esther, E. Sugar: Does it really cause hyperactivity? Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2020. Available online: https://www.eatright.org/food/nutrition/dietary-guidelines-and-myplate/sugar-does-it-really-cause-hyperactivity (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Burns, J. Organic Foods vs Regular Conventional Food: What Is the Difference? The Diabetes Council. 2020. Available online: https://www.thediabetescouncil.com/organic-foods-vs-regular-conventional-food-what-is-the-difference/ (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- Vigar, V.; Myers, S.; Oliver, C.; Arellano, J.; Robinson, S.; Leifert, C. A Systematic Review of Organic Versus Conventional Food Consumption: Is There a Measurable Benefit on Human Health? Nutrients 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, M.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Średnicka, D.; Bügel, S.; Van De Vijver, L.P.L. Organic food and impact on human health: Assessing the status quo and prospects of research. NJAS–Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2011, 58, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrace, B.W. The everyday occupation of families with children with autism. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2004, 58, 543–550. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15481781/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Montes, G.; Halterman, J.S. Psychological functioning and coping among mothers of children with autism: A population-based study. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e1040–e1046. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17473077/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Ateah, C.; Secco, L. Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qual. Heal. Res. 2008, 18, 1075–1083. Available online: /record/2008-11328-005 (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M. Evidence of resilience in families of children with autism. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2007, 51, 702–714. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00960.x (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Dia, M.J.; DiNapoli, J.M.; Garcia-Ona, L.; Jakubowski, R.; O’Flaherty, D. Concept analysis: Resilience. Arch. Psychiatr Nurs. 2013, 27, 264–270. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24238005/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Kuhaneck, H.M.; Burroughs, T.; Wright, J.; Lemanczyk, T.; Darragh, A.R. A qualitative study of coping in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2010, 30, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiman, T. Parents’ voice: Parents’ emotional and practical coping with a child with special needs. Psychology 2021, 12, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, K.; Cornish, K.; Park, M.S.A.; Toran, H.; Golden, K.J. Risk and resilience among mothers and fathers of primary school age children with ASD in Malaysia: A qualitative constructive grounded theory approach. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, B.; Moss, M.; Wetherell, M.A. With a little help from my friends: Psychological, endocrine and health corollaries of social support in parental caregivers of children with autism or ADHD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsack, C.N.; Samuel, P.S. Mediating effects of social support on quality of life for parents of adults with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2378–2389. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10803-017-3157-6 (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balubaid, R.; Sahab, L. The coping strategies used by parents of children with autism in Saudi Arabia. J. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, J.C.; Carter, A.S. Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2006, 76, 564–575. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17209724/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.A.; Cappadocia, M.C.; MacMullin, J.A.; Viecili, M.; Lunsky, Y. The impact of child problem behaviors of children with ASD on parent mental health: The mediating role of acceptance and empowerment. Autism 2012, 16, 261–274. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22297202/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G.; Jones, E.J.H.; Merkle, K.; Venema, K.; Lowy, R.; Faja, S.; Kamara, D.; Murias, M.; Greenson, J.; Winter, J.; et al. Early behavioral intervention is associated with normalized brain activity in young children with autism. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2012, 51, 1150–1159. Available online: https://pmc/articles/PMC3607427/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Reaven, J.; Blakeley-Smith, A.; Culhane-Shelburne, K.; Hepburn, S. Group cognitive behavior therapy for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders and anxiety: A randomized trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2011, 53, 410–419. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22435114/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Reichow, B.; Hume, K.; Barton, E.E.; Boyd, B.A. Early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD009260. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009260.pub3/full?cookiesEnabled (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Vivanti, G.; Dissanayake, C. Outcome for children receiving the early start denver model before and after 48 months. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 2441–2449. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10803-016-2777-6 (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitlauf, A.S.; McPheeters, M.L.; Peters, B.; Sathe, N.; Travis, R.; Aiello, R.; Williamson, E.; Veenstra-VanderWeele, J.; Krishnaswami, S.; Jerome, R.; et al. Therapies for children with autism spectrum disorder: Behavioral interventions update. Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014; 120p. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK241444/ (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Gray, D.E. Coping over time: The parents of children with autism. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shilubane, H.; Mazibuko, N. Understanding autism spectrum disorder and coping mechanism by parents: An explorative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G.; Fewster, D.L.; Gurayah, T. Parents’ voices: Experiences and coping as a parent of a child with autism spectrum disorder. South Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 49, 43–50. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2310-38332019000100007&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Simmons, B.A. Perceptions of Well-Being and Coping Mechanisms from Caregivers of Individuals with Autism. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Walden University. 2019. Available online: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/6671 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

- Gentles, S.J.; Nicholas, D.B.; Jack, S.M.; McKibbon, K.A.; Szatmari, P. Coming to understand the child has autism: A process illustrating parents’ evolving readiness for engaging in care. Autism 2020, 24, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.R.; Freeston, M.H.; Honey, E.; Rodgers, J. Facing the unknown: Intolerance of uncertainty in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 30, 336–344. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26868412/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R.; Wood, C.E.; Jellett, R.; Porter, R. Fatigue, wellbeing and parental self-efficacy in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2013, 17, 465–480. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21788255/ (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.R.; Patterson, B.J.; Klein, J. Coping with autism: A journey toward adaptation. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012, 27, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, B.J.; Mackintosh, V.H.; Goin-Kochel, R.P. “My greatest joy and my greatest heart ache:” parents’ own words on how having a child in the autism spectrum has affected their lives and their families’ lives. Res. Autism. Spectr. Disord. 2009, 3, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.; Norwich, B. Dilemmas, diagnosis and de-stigmatization: Parental perspectives on the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christina, G. Five Stages of Grief—Understanding the Kubler-Ross Model. Remedy Health Media. 2021. Available online: https://www.psycom.net/depression.central.grief.html (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Siah, P.C.; Tan, S.H. Relationships between sense of coherence, coping strategies and quality of life of parents of children with autism in Malaysia: A case study among chinese parents. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2016, 27, 78–91. Available online: http://dcidj.org//articles/10.5463/dcid.v27i1.485/ (accessed on 22 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Brookman-Frazee, L.; Stahmer, A.; Baker-Ericzén, M.J.; Tsai, K. Parenting Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum and Disruptive Behavior Disorders: Opportunities for Cross-Fertilization. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 9, 181–200. Available online: /pmc/articles/PMC3510783/ (accessed on 5 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First, I will ask you some questions about your child’s eating behavior. |

|

| Second, I will ask related to healthy eating. |

|

| Third, I will ask about coping strategies. Some studies showed that taking care of autistic children experiences higher stress levels than typical children. |

|

| Initial Quotes | Codes | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| “For my child, I noticed that he is quite selective with his food; he prefers to only to eat his favorite food, which consist of a small selection of assorted local kuih (dessert), fruits, and colored rice. These are the main foods for him. So, for my part, I will only add on his few favorite side dishes such as anchovies and or egg.” (P3) “...my child refuses to eat. She only eats vermicelli noodle soup. She will keep throwing tantrums, screaming and shouting…as if we are torturing her.” (P5) | Limited food repertoire up to refusing to eat. | Feeding problems |

| “[Laughter from a parent] My child likes spicy food. He refuses any food that comes with clear-soup based. Something like sambal (chili) chicken or curry fish, he will finish the food. If the foods color combination looks dull, he refuses to eat too.” (P4) | Being very selective with the food presentation, only to one’s liking. | |

| “During his eating time, my child will fully focus while eating. We are not allowed to disturb him. And if he already selects an eating place, he will not go to other places. And even for the eating utensils, he also got his specific plate colors.” (P9) | Selective in designated place and utensils |

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Male | 11 (73%) |

| Female | 4 (27%) |

| Child age (years old) | |

| 5 | 3 (20%) |

| 6 | 2 (13%) |

| 7 | 4 (27%) |

| 8 | 1 (7%) |

| 9 | 1 (7%) |

| 10 | 2 (13%) |

| 11 | 2 (13%) |

| Parent education level | |

| Completed degree and above | 10 (67%) |

| Primary and secondary | 5 (33%) |

| Parent occupations | |

| Housewife | 7 (47%) |

| Public officers | 5 (33%) |

| Self-employed | 3 (20%) |

| Total household income | |

| Less than RM 4339 | 15 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, W.Y.; Hamzaid, N.H.; Ibrahim, N. Parental Perceptions on the Importance of Nutrients for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071608

Tan WY, Hamzaid NH, Ibrahim N. Parental Perceptions on the Importance of Nutrients for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(7):1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071608

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Woan Yin, Nur Hana Hamzaid, and Norhayati Ibrahim. 2023. "Parental Perceptions on the Importance of Nutrients for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study" Nutrients 15, no. 7: 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071608

APA StyleTan, W. Y., Hamzaid, N. H., & Ibrahim, N. (2023). Parental Perceptions on the Importance of Nutrients for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and the Coping Strategies: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients, 15(7), 1608. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071608